Abstract

Noncompetitive inhibitors of the nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors suppress cation flux directly by binding in and blocking the open channel or indirectly by stabilizing closed states of the receptor. The lidocaine derivative QX-314 and the acridine derivative quinacrine act directly as open channel blockers, but can act indirectly as well. The binding site for quinacrine in the open channel of mouse-muscle ACh receptor was mapped in cysteine-substituted mutants of the α subunit expressed with wild-type β, γ, and δ subunits. In the open state, substituted cysteines in the inner half of the second membrane-spanning segment (M2), but not in the outer half, were protected by quinacrine from reaction with 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate. In addition, an alkylating derivative, quinacrine mustard, affinity labeled a subset of the substituted cysteines in M2, but only in the open state. These results, mapped onto a model of the open channel surrounded by five α-helical M2s, imply that quinacrine binds midway down M2 in the same site previously mapped for QX-314. A cysteine substituted for a residue in the outer third of αM1, which reacted with 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate only in the presence of ACh, reacted faster in the additional presence of quinacrine or QX-314. It is proposed that channel opening involves both the opening of the resting gate at the inner end of M2 and the removal of an obstruction formed by the outer end of M1 that retards diffusion of blockers into the closed channel. Blocker binding in the open channel causes a further change in structure.

Binding of acetylcholine (ACh) to nicotinic ACh receptors in the resting state leads to an open state and in the continued presence of ACh to a closed, desensitized state (1, 2). These receptors consist of five subunits that are either homologous or identical (3, 4). The subunits have a large extracellular domain, four membrane-spanning segments (M1–M4), and an intracellular domain. The subunits surround a central channel. The structure of the extracellular domain is known in great detail thanks to a wealth of biochemical and mutagenetic results (3, 4), a high-resolution structure of a homopentameric ACh-binding protein homologous to the extracellular domain of the ACh receptor (5), and cryoelectron microscopy of two-dimensional crystals of ACh receptor in membrane (6). The three-dimensional structures of the membrane domain and the cytoplasmic domain are less well established.

The structure of the membrane domain and the channel have been studied in receptors from electric cells and muscle, subunit composition (α1)2(β1)γδ or (α1)2(β1)ɛδ, and homopentameric neuronal receptor composition (α7)5 (3, 4). The channel lumen is lined by the M2 segments from the five subunits (refs. 7–9; Fig. 1A). Residues in M2 were labeled by photoactivated (9, 10) and electrophilic (11) noncompetitive inhibitors. In addition, mutations of residues in M2 altered the effectiveness of open-channel blockers (12, 13). All of the residues that line the channel lumen in the M2 segments of the mouse-muscle ACh receptor α and β subunits were identified by the substituted cysteine accessibility method, which identifies Cys accessible to water and to small, polar reagents, and the pattern of accessibility conformed largely to an exposed stripe of an α-helix (14, 15).

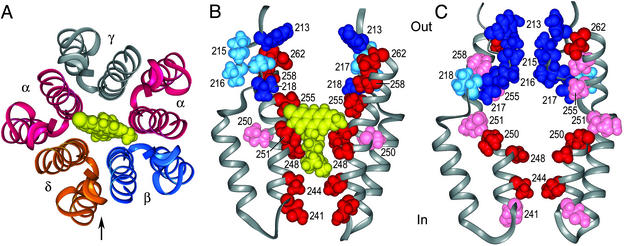

Figure 1.

Models of M1, M2, and the connecting loop in the resting and blocked open states are shown. The helical segments were generated with INSIGHT II and the nonhelical segments were generated with the MODELER program (16). (A) Symmetrical pentamer of M1, M2, and the M1–M2 loop, with the sequence of mouse-muscle α, in the blocked open state, seen from the extracellular side, with quinacrine (yellow) in the channel. Although the model is homopentameric, the arrangement of subunits in the α2βγδ complex is indicated. The arrow marks the direction of the view in B and C. (B) View parallel to the membrane of two M1–loop–M2s in the positions of the α subunits in A, in the blocked open state. Side chains are color-coded for relative reactivity toward MTSEA added extracellularly in the open (not blocked) channel as follows: dark blue, M1 and reactive; light blue, M1 and unreactive; red, M2 and reactive; pink, M2 and unreactive. (C) View parallel to the membrane of two M1–loop–M2s in the positions of α in the resting state. Side chains are color-coded as in B for relative reactivity in the resting state. The sequence modeled is P211LYFIVNVIIP221CLLFSFLTSL231VFYLPTDSGE241KM1′TLSISVLL251SL11′TVFLLVIV261E. The numbering is that of the mature mouse-muscle α subunit; the primed numbers refer to the position in the predicted M2 sequence.

Residues in the M1 segments also contribute to the channel lining. Quinacrine azide (17), a derivative of the open-channel blocker quinacrine (18–20), photolabeled residues at the extracellular end of αM1 specifically in the open state of the receptor (21–23). In addition, a number of substituted Cys in the outer third of M1 are accessible from the channel lumen either in the resting state or in the open state (15, 24, 25). The pattern of accessibility was inconsistent with a regular secondary structure in this region. The accessibility of residues in the outer third of M1 is consistent, at least in the open state, with a funnel-shaped lumen (26) lined with alternating M1 strands and M2 helices at its wide outer end and by just five M2 helices at its narrow inner end (Fig. 1B; refs. 14, 15, 24, 25, and 27).

The narrow inner end of the channel contains rings of aligned residues in the M1–M2 loops and the inner ends of M2 that are the principal determinants of conductance (28), size selectivity (29–31), and charge selectivity (32). The resting (activation) gate has been proposed to be in the middle of the membrane (33) or alternatively at the inner end of the channel (34). Furthermore, the gate in the desensitized state has been proposed to extend from the inner end to the middle of the channel (35). The gates at the inner end of the channel block the passage of 2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSEA) from inside and from outside.

In the work presented here, we used quinacrine (18–20) and quinacrine mustard (36, 37) to explore the accessibility of the channel lumen to relatively large molecules in the resting and open states. As was previously done with QX-222 and QX-314 (38), we mapped the binding site of quinacrine by its protection of Cys-substitution mutants in αM1 and αM2 against MTSEA. We also characterized the covalent reaction of quinacrine mustard, an alkylating derivative of quinacrine, with these cysteines. The results were consistent with quinacrine and quinacrine mustard binding in the open channel on the intracellular side of αV255 (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, in contrast to the protection by quinacrine of substituted Cys in M2 below αV255, the reaction of αV218C in M1 with MTSEA was faster in the quinacrine-blocked open state than in the unblocked open state, which is evidence of the state-dependent dynamics of the outer end of the channel.

Materials and Methods

Quinacrine was from Sigma, quinacrine mustard was from Fluka, 2-(triethylammonio)-N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)acetamide bromide (QX-314) was from Alomone Laboratories (Jerusalem), and MTSEA was from Toronto Research Chemicals (Downsville, ON, Canada).

All mutations were introduced in the M1 and M2 segments of the mouse muscle α subunit and expressed with wild-type β, γ, and δ subunits in Xenopus laevis oocytes as described (14, 24).

Currents were recorded from oocytes under a two-electrode voltage clamp as described (38). The oocyte bath solution contained (in mM) 115 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.8 MgCl2, and 10 Hepes, pH 7.2 (CFFR). The responses to ACh of wild-type and mutant receptors were determined by the application of 7- to 10-s pulses of ACh at ≥5× EC50 unless otherwise noted. The holding potential was −50 mV.

Rate constants for MTSEA reactions were determined as follows. Oocytes were treated several times alternately with ACh alone and with a mixture of ACh and MTSEA or with a mixture of ACh, MTSEA, and blocker (quinacrine or QX-314). The test current (I) elicited by a fixed concentration of ACh after each application of MTSEA, as a function of the cumulative time (t) of application of MTSEA, was fitted by I = I∞ + (I0 − I∞)e−kmt, where I∞ is the test current at infinite t, I0 is the initial test current, k is the second-order rate constant, and m is the concentration of MTSEA. I∞ and k were obtained from the fit. The observed rate constant, kobs, for the MTSEA reaction in the presence of ACh and blocker was assumed to be equal to ykblocked + (1 − y)kopen, where y is the fraction of blocked channels, kblocked is the rate constant for the reaction with fully blocked channels, and kopen is the rate constant for the reaction with open (not blocked) channels. For y = 1/(1 + IC50/q), where q is the blocker concentration, kblocked/kopen = (kobs/kopen − 1)/y + 1, which we used to extrapolate kobs to the fully blocked state (38).

Results and Discussion

Quinacrine Inhibition of Cys Mutants.

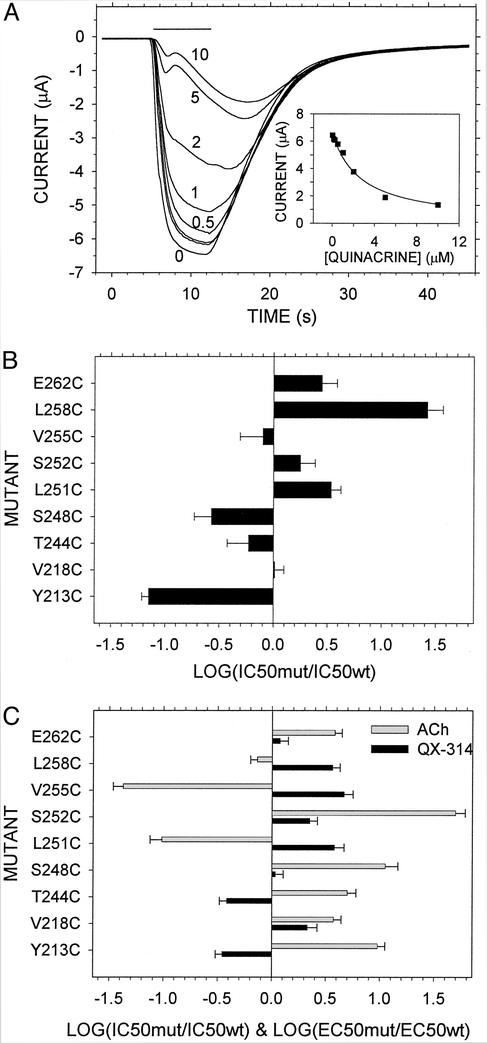

Quinacrine inhibited the current evoked by a high concentration of ACh in oocytes expressing wild-type and Cys-substituted receptors (Fig. 2A). The quinacrine concentration (IC50) that inhibited current by 50% was 2.7 μM for wild type and ranged from 14 times smaller than wild type for αY213C to 27 times larger than wild type for αL258C (Fig. 2B). Neither of these residue's contacts bound quinacrine (see below). Mutations of those residues that do contact quinacrine had modest effects on the IC50, consistent with Cys being a highly tolerated substitute for other residues. The IC50 of another channel blocker, QX-314, was affected similarly by most of the mutations (Fig. 2C). The effects of the mutations on IC50 do not correlate with the effects on the concentration (EC50) of ACh eliciting half-maximal current. Because the mutated residues are distant from the ACh binding sites, the effects of the mutations on EC50 must be through effects on the relative stability of the open state. The lack of correlation between the effects on EC50 and the effects on IC50 implies that effects on the relative stability of the open state do not alone account for the effects on IC50. Previously, the mutations of αR209, αP211, and αY213 were found to affect quinacrine inhibition of ACh-induced current (39).

Figure 2.

Quinacrine inhibition of ACh-induced currents in Cys mutants is shown. (A) An oocyte expressing wild-type receptor was treated sequentially with 1 μM ACh and 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 μM quinacrine (bar). After 7 s, the oocyte was washed with CFFR for 180 s. The sequential responses are superimposed in the plot. The maximum current during the 7 s was taken as the response. These responses are plotted in the Inset and are fit by I = I0/(1 + q/IC50), where I is the current, I0 is the current at zero quinacrine, and q is the quinacrine concentration. (B) The IC50 for quinacrine of the mutants is normalized by the IC50 of wild type (2.7 ± 0.2 μM). (C) The IC50 for QX-314 of the mutants is normalized by the IC50 of wild type (78 ± 12 μM), and the EC50 for ACh of the mutants is normalized by the EC50 of wild type (2.6 ± 0.4 μM). The IC50 values for QX-314 for all mutants except Y213C and V218C were from ref. 38. The EC50 was from refs. 14 and 24.

Quinacrine Effects on the Reaction of MTSEA with Cys Mutants.

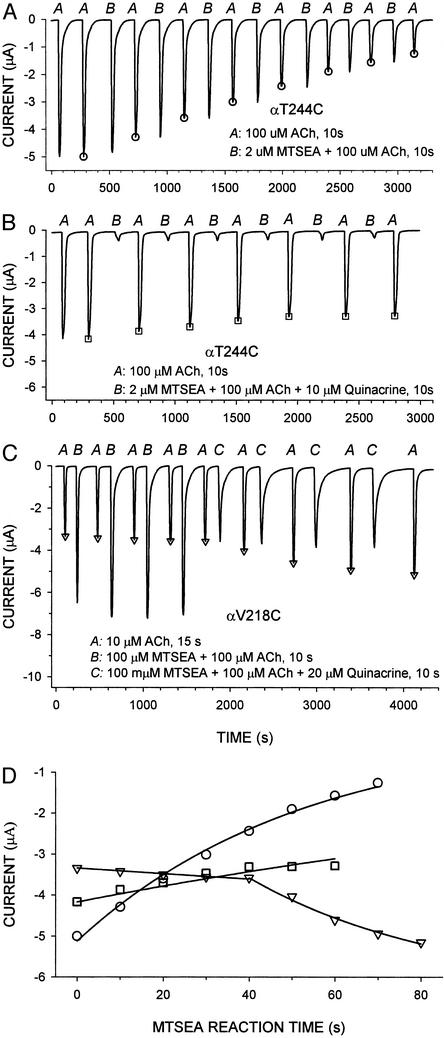

We mapped the binding site of quinacrine by determining its effect on the reactions of MTSEA with Cys substituted for residues known to react in the open state. The rate constant for the MTSEA reaction in the presence of ACh (Fig. 3A) was compared with the rate constant in the presence of both ACh and quinacrine (Fig. 3B). For some mutants, the reactions in the absence and presence of quinacrine were followed in the same oocyte (Fig. 3C). The test responses were fitted by a pseudo-first-order kinetic equation (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Effects of quinacrine on the reactions of MTSEA with the mutant receptors αT244C and αV218C in the open state. Oocytes were treated alternately with ACh alone and with a mixture of ACh and MTSEA or with a mixture of ACh, MTSEA, and quinacrine. Following each of these additions, the oocytes were washed with CFFR for at least 180 s. The extent of reaction of MTSEA was taken as proportional to its effect on the response to ACh. The additions to the oocytes are indicated by the italicized letters above the current recording. (A) αT244C was treated alternately with 100 μM ACh alone (“A”) applied for 10 s and with 100 μM ACh + 2 μM MTSEA (“B”) for 10 s. The values taken as the test responses to ACh are marked with circles. (B) αT244C was treated alternately with 100 μM ACh alone (“A”) for 10 s and with 10 μM quinacrine alone for 15 s, immediately followed by 100 μM ACh + 2 μM MTSEA + 10 μM quinacrine (“B”) for 10 s. The currents taken as the test responses to ACh are marked with squares. (C) αV218C was treated alternately with 10 μM ACh (EC50) alone (“A”) for 15 s and with 100 μM ACh + 100 μM MTSEA (“B”) for 10 s (four cycles) and then with 10 μM ACh alone for 15 s (“A”) and with 20 μM quinacrine alone for 15 s immediately followed by 100 μM ACh + 100 μM MTSEA + 20 μM quinacrine (“C”) for 10 s (four cycles). The currents taken as the test responses are marked with triangles. (D) ACh-evoked current (I) as a function of the duration (t) of the MTSEA reaction. The peak test currents in A (○), B (□), and C (▿) were fitted by an exponential function (see Materials and Methods). The test currents in C corresponding to reaction times 0–40 s, in the absence of quinacrine, and those for reaction times 40–80 s, in the presence of quinacrine, were fitted separately. The fit yields the second-order rate constants 9,500 ± 300 M−1·s−1 for A, 2,450 ± 180 M−1·s−1 for B, and 23.7 ± 1.5 M−1·s−1 (absence of quinacrine) and 220 ± 76 M−1·s−1 (presence of quinacrine) for C.

In the inner half of M2, the rate constants of the MTSEA reactions with αT244C, αS248C, and αL251C in the quinacrine-blocked open state were <10% the rate constants in the open state in the absence of quinacrine (Fig. 4), i.e., the protection was >90%. There was no protection of αT244C in the absence of ACh. In the presence of ACh, the reaction with αV255C, one helical turn up from αL251, was protected only ≈40% by quinacrine binding, and αL258C and αE262C were not at all protected.

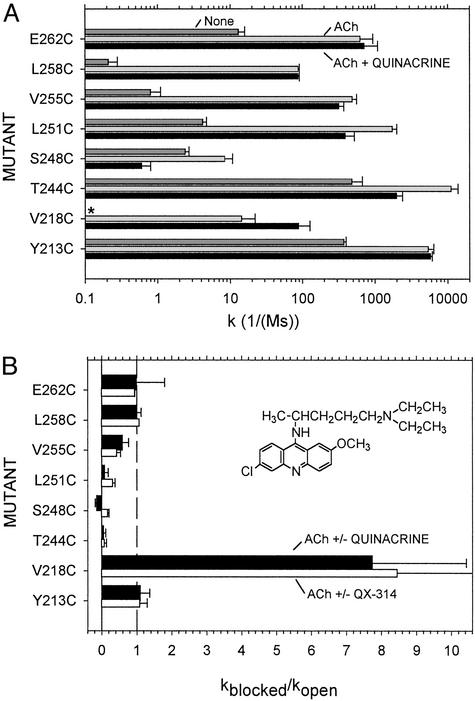

Figure 4.

Quinacrine effects on the rate constants for the reactions of Cys mutants with MTSEA are shown. (A) The rate constants were determined as in Fig. 3 and are the means of two to six determinations. The rate constants in the presence of blocker are those observed, uncorrected for extent of occupation. The rate constants for MTSEA alone (medium gray bars) for the mutants other than Y213C are from ref. 45. MTSEA alone did not react detectably with V218C (*). (B) The ratio of the rate constants in the presence and absence of either quinacrine or QX-314. A value of 1 indicates no effect on the rate. The ratios of the rate constants are corrected to complete occupation by blocker (see Materials and Methods). (Inset) Quinacrine.

The protection was most likely due to the binding of quinacrine in the open channel starting just below αV255, where it blocked access to the residues that it contacted and the residues below by occluding the lumen (Fig. 1 A and B). αV255 was also inferred to be the upper boundary of the QX-314 and QX-222 binding site (Fig. 4B; ref. 38). An alternative explanation for the protection is that quinacrine bound elsewhere than in the channel (40, 41) and stabilized, for example, a desensitized state (40, 42–44), in which the protected residues were unreactive. Such a state, however, could not have been the stable desensitized state, in which αL251C reacts nearly as fast as in the open state (35), and it could not have been the resting state, in which both αV255C and αL258C react very slowly with MTSEA (Fig. 4A; ref. 45). Neither of these patterns of reactivity resembles the pattern of reactivity of the blocked open state. Moreover, two other lines of evidence support the binding of quinacrine within the open channel, stabilizing an open-like structure. One is the effect of quinacrine on the reactivity of αV218C, and another is the pattern of reaction of quinacrine mustard.

αV218C reacted with MTSEA only in the open state (ref. 24; Fig. 4A). This reaction resulted initially in potentiation of ACh responses (Fig. 3C). After longer reaction of MTSEA, application of ACh resulted in a persistent current even after ACh was removed (not shown). Quinacrine increased the rate constant for the MTSEA reaction by a factor of 8 (Fig. 4). QX-314 had the same effect (Fig. 4B). These effects of blockers were not simply due to the stabilization of the open conformation of the channel. The reactivities with MTSEA of other mutants, like αL258C and αY213C, were greater in the presence than in the absence of ACh. Yet, the additional presence of quinacrine had no effect on their rates of reaction (Fig. 4). Hence, the structures of the open channel and the blocked open channel are somewhat different.

Quinacrine Mustard Reaction with Cys Mutants.

Quinacrine mustard contains a bis-(2-chloroethyl)amino group in place of the diethylamino group in quinacrine (Fig. 5 Inset). Each 2-chloroethyl group can react with a nucleophile like an S− or an NH2, presumably through an aziridinium intermediate. Previously, 10 μM quinacrine mustard applied 5 min to reconstituted receptor from Torpedo electric tissue was found to inhibit ACh-induced Rb+ flux irreversibly (37). The inhibition was greater in the presence of carbamoylcholine or D-tubocurarine, and the receptor was protected by proadifen. The incorporation of radioactive quinacrine mustard into the α and β chains was increased by both carbamoylcholine and D-tubocurarine. It is unlikely in this case that the observed inhibition and incorporation were mainly due to reaction in the open channel.

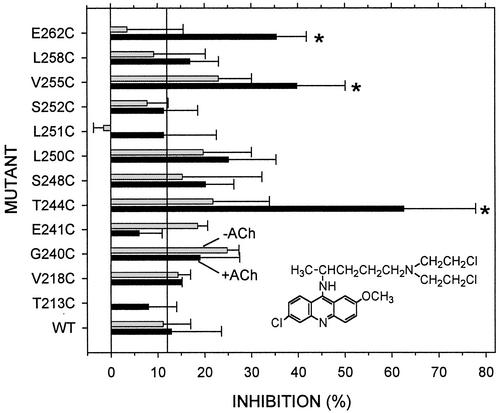

Figure 5.

The irreversible effects of quinacrine mustard on Cys mutants are shown. Each mutant and wild type was reacted for 1 min with 10 μM quinacrine mustard in the presence and in the absence of ACh, and the mean extent of inhibition (n = 2–13) of the current evoked by ACh at >5× EC50 was determined. The effects on mutants that were significantly different from the effect on wild type (ANOVA, Dunnett's test, P < 0.05) are indicated by asterisks. A line at the average inhibition of wild type in presence and absence of ACh is shown. (Inset) Quinacrine mustard.

Under milder conditions, 10 μM quinacrine mustard applied to oocytes expressing wild-type mouse-muscle ACh receptor for 1 min in the presence of ACh at ≥5× EC50, or in the absence of ACh, irreversibly inhibited the subsequent response to ACh ≈10% (Fig. 5). Under the same conditions, the effect of QM was tested on Cys-substitution mutants in αM1 and αM2 (Fig. 5). In the presence of ACh, but not in its absence, quinacrine mustard irreversibly inhibited αT244C, αV255C, and αE262C. No other tested mutant in M1 or M2 was inhibited significantly more than wild type in the presence or absence of ACh.

The rate constants for the reactions of quinacrine mustard with the three reactive mutants were three to five orders of magnitude greater than the rate constant for the reaction of quinacrine mustard with 2-mercaptoethanol in buffer with the same ionic strength and pH as CFFR (Table 1). This acceleration was not due to the unusual reactivity of the Cys sulfhydryls in these mutants because another nucleophile MTSEA reacted considerably more slowly with these mutants than with 2mercaptoethanol in solution (45). Rather, the acceleration is consistent with quinacrine mustard acting as an affinity label of these Cys-substituted residues. In our model of the channel, when the acridine moiety of quinacrine mustard is bound between αV255 and αL251, the aliphatic N-bis-(2-chloroethyl)pentylamine moiety reaches down to αT244C (Fig. 1B). With the acridine ring system bound in the same location but flipped over, the reactive groups on the aliphatic moiety are juxtaposed to αE262C. In a configuration in which the bis(2-chloroethyl)pentylamine is tangential to the acridine, the reactive groups are juxtaposed to αV255C (not shown).

Table 1.

Rate constants for quinacrine mustard reactions with Cys mutants and with 2-mercaptoethanol

| Rate constant | Cys mutant

|

2-Mercaptoethanol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T244C | V255C | E262C | ||

| k, M−1·s−1 | 4,930 ± 1,100 (3) | 520 ± 150 (3) | 146 ± 23 (2) | 0.044 ± 0.013 (2) |

| kMut/k2ME | 112,000 | 11,800 | 3,320 | 1 |

Oocytes expressing mutant receptors were treated alternately with ACh at ≥5× EC50 for 5–10 s and with 5 μM (T244C) or 100 μM (V255C and E262C) quinacrine mustard and ACh (same concentration as in test responses) for 10 s. The oocyte was washed with CFFR for 3–5 min after each application of ACh with and without quinacrine mustard. The equation I = Io + (Iinf − Iinf)e−kqt, where q is the quinacrine mustard concentration, was fit to the peak currents of the test responses as a function of the reaction time, and yielded k, the second-order rate constant. Quinacrine mustard (100 μM) in 115 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes, and 1 mM EDTA (pH 7.2) was mixed with 2-mercaptoethanol (final concentration 122 μM). The mixture was kept at 23°C under argon, and 0.5-ml aliquots were taken initially and every hour for 6 h. The aliquots were mixed with 400 μM DTNB in 200 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0). The absorbance at 412 nm was divided by 13,600 to obtain the remaining SH concentration. The SH concentration in the reaction mixture as a function of time was fitted with a second-order kinetic equation to obtain the rate constant. The mean rate constants, the mean error, and the number of determinations are given.

In the open state, αL251C and αV255C reacted with nearly equal rate constants with MTSEA (45). Thus, the lack of reaction of quinacrine mustard with αL251C was not due to its low intrinsic reactivity but to steric hindrance by the closely bound acridine moiety. The lack of significant reaction of quinacrine mustard with αL258C, αS248C, and αV218C was likely due to the relatively low reactivity of these cysteines even in the presence of ACh (ref. 45; Fig. 4). αY213C is relatively reactive toward MTSEA, but it may be further from the acridine binding site than αE262. αR209 and αP211 are presumably even further from αV255 than αY213; yet, quinacrine azide photolabeled them specifically in the open state, and this labeling was blocked by other noncompetitive inhibitors (21–23). Either the photogenerated quinacrine nitrene diffused up from the open channel below or was bound outside of the lumen (41). The pattern of the highly enhanced reactions of quinacrine mustard is consistent with the binding of its acridine moiety just below αV255, the same location for the binding site that we inferred from the protection of substituted Cys by quinacrine and previously by QX-314 (38). This evidence, however, does not exclude other binding sites for quinacrine.

Structural Implications.

Based on protection of substituted Cys by quinacrine, QX-314, and QX-222 (38) and on the affinity reactions of these cysteines with quinacrine mustard, as well as the photoreactions of chlorpromazine (10), these blockers bind just below αV255 in the open channel. Quinacrine and QX-314 (38) did not protect, and quinacrine mustard did not alkylate, substituted Cys in the resting channel. One possibility is that there is an obstruction at the outer end of the resting channel that hinders passage of channel blockers but allows passage of smaller molecules like MTSEA. MTSEA added extracellularly (but not intracellularly) reacted with Cys in the inner half of M2 in the resting state (34, 45). MTSEA, however, reacted particularly slowly with αV255C and αL258C in the outer half of M2 in the resting state. Furthermore, 2-aminoethyl-2-aminoethane thiosulfonate, intrinsically more reactive than MTSEA but twice as big, reacted faster than MTSEA with Cys in the inner half of M2 in the open state but much more slowly in the resting state (45), which is also consistent with a partial obstruction in the resting state. A loop formed by three consecutive M1 residues, αI215, αV217, and αN217, could obstruct the channel and also hinder access to and ionization of αV255C and αL258C in the resting state (ref. 27; Fig. 1C). Cys substituted for αI215, αV216, and αN217 reacted with MTSEA in the resting state but not in the open state (24). Furthermore, the Cys substituted for the next residue in αM1, αV218, was completely unreactive in the resting state and slowly reactive in the open state (Fig. 4). Thus, a rearrangement in M1 that pulled back the obstructing loop and buried residues 215–217 could also expose αV218 between the flanking M2 segments. That αV218 is buried in the resting state and exposed to water in the open state is consistent with the potentiating effect of the reaction of MTSEA with αV218C; the channel with αV218C chemically modified by MTSEA to resemble a lysyl residue did not close completely.

Some relatively hydrophobic noncompetitive inhibitors after a 5- to 60-min incubation photolabel the same M2 residues in the closed, resting channel (9, 46, 47) that contact quinacrine bound in the open channel. Thus, if M1 does form an obstructing loop, it must fluctuate sufficiently to allow passage of these inhibitors. Although quinacrine and QX-314 failed to protect αT244C against MTSEA in the absence of ACh, we would not have detected their diffusion past the M1 loops if it were slow compared with the diffusion and reaction of MTSEA. Similarly, although quinacrine mustard failed to react with M2 Cys in the absence of ACh, we would not have detected the reaction if the time constant for diffusion of quinacrine mustard past the loops were >1 min.

The relatively small rate constant for the reaction of αV218C in the open state with MTSEA suggests that it is narrowly exposed (Fig. 4A). That the addition of quinacrine increased the rate constant by an order of magnitude suggests that the binding of quinacrine in the open channel spreads the M2 segments slightly, further exposing αV218C to water and to MTSEA. By contrast, based on the rate constants for their reactions, αY213C, αL258C, and αE262C are already highly exposed in the open state, and spreading the M2 segments would not expose them any further. Because QX-314 had the same effect on the rate constant for the reaction of MTSEA with αV218C, the structural difference between the open channel and the blocked open channel was not due to the size of quinacrine alone. The increased reactivity of αV218C must be a characteristic of the blocked open state. The blocked open channel must accommodate the 14-Å-long substituted acridine moiety of quinacrine at the level of αV255 (Fig. 1B; cf. ref. 48). By comparison, the width at the narrowest part of the open channel at the level of αT244 (29–31) is ≈7.5 Å (31, 49, 50).

The accessibility of the residues in β M1 aligned with α215–217 was not different in the resting and open states. However, the Cys mutant of βV229, which aligns with αV218, also reacted with MTSEA only in the open state. Furthermore, the reaction of βV229C in the open state with the doubly charged 2-aminoethyl-2-aminoethane thiosulfonate depended on membrane potential, placing this residue in the open channel lumen (25). That α and β make different contributions to the channel structure is consistent with other observed asymmetries in the contributions of the subunits (51, 52). The accessibilities of γ and δ at the outer end of the channel have not yet been mapped. Not to overcomplicate the model, which is intended to be schematic but with realistic dimensions, we drew it symmetrically (Fig. 1A). The hypothesis that loops in αM1 are juxtaposed in the resting state should be testable.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Pascual, H. Zhang, and M. Sonders for advice and H. R. Kaback for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant NS07065.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- MTSEA

2-aminoethyl methanethiosulfonate

Note Added in Proof.

The rate constant for the reaction of MTSEA with βV229C, just as with the aligned αV218C, was increased eight times by quinacrine and seven times by QX-314.

References

- 1.Sakmann B, Patlak J, Neher E. Nature. 1980;286:71–73. doi: 10.1038/286071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auerbach A, Akk G. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlin A. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corringer P J, Le Novere N, Changeux J P. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:431–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brejc K, van Dijk W J, Klassen R V, Schuurmans M, van der Oost J, Smit A B, Sixma T K. Nature. 2001;411:269–276. doi: 10.1038/35077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unwin N, Miyazawa A, Li J, Fujiyoshi Y. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imoto K, Busch C, Sakmann B, Mishina M, Konno T, Nakai J, Bujo H, Mori Y, Fukuda K, Numa S. Nature. 1988;335:645–648. doi: 10.1038/335645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraudat J, Dennis M, Heidmann T, Haumont P-Y, Lederer F, Changeux J-P. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2410–2418. doi: 10.1021/bi00383a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hucho F, Oberthur W, Lottspeich F. FEBS Lett. 1986;205:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revah F, Galzi J L, Giraudat J, Haumont P Y, Lederer F, Changeux J P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4675–4679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pedersen S E, Sharp S D, Liu W S, Cohen J B. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10489–10499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charnet P, Labarca C, Leonard R J, Vogelaar N J, Czyzyk L, Gouin A, Davidson N, Lester H A. Neuron. 1990;4:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90445-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revah F, Bertrand D, Galzi J L, Devillers-Thiery A, Mulle C, Hussy N, Bertrand S, Ballivet M, Changeux J P. Nature. 1991;353:846–849. doi: 10.1038/353846a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akabas M H, Kaufmann C, Archdeacon P, Karlin A. Neuron. 1994;13:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Karlin A. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7952–7964. doi: 10.1021/bi980143m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiser A, Do R K G, Sali R. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxford G S, Hudson R A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;104:1579–1584. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grunhagen H H, Changeux J P. J Mol Biol. 1976;106:517–535. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai M C, Oliveira A C, Albuquerque E X, Eldefrawi M E, Eldefrawi A T. Mol Pharmacol. 1979;16:382–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams P R, Feltz A. J Physiol (London) 1980;306:283–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox R N, Kaldany R R, DiPaola M, Karlin A. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7186–7193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiPaola M, Kao P N, Karlin A. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11017–11029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlin A. Harvey Lect. 1991;85:71–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akabas M H, Karlin A. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12496–12500. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Karlin A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15856–15864. doi: 10.1021/bi972357u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyazawa A, Fujiyoshi Y, Stowell M, Unwin N. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:765–786. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlin A, Akabas M H. Neuron. 1995;15:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konno T, Busch C, Von Kitzing E, Imoto K, Wang F, Nakai J, Mishina M, Numa S, Sakmann B. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1991;244:69–79. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villarroel A, Herlitze S, Koenen M, Sakmann B. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1991;243:69–74. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imoto K, Konno T, Nakai J, Wang F, Mishina M, Numa S. FEBS Lett. 1991;289:193–200. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81068-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen B N, Labarca C, Davidson N, Lester H A. J Gen Physiol. 1992;100:373–400. doi: 10.1085/jgp.100.3.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corringer P J, Bertrand S, Galzi J L, Devillers-Thiery A, Changeux J P, Bertrand D. Neuron. 1999;22:831–843. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unwin N. Nature. 1995;373:37–43. doi: 10.1038/373037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson G G, Karlin A. Neuron. 1998;20:1269–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson G G, Karlin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1241–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031567798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauffer L, Weber K H, Hucho F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;587:42–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaldany R R, Karlin A. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:6232–6242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pascual J M, Karlin A. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:611–621. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.5.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamamizu S, Todd A P, McNamee M G. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:427–438. doi: 10.1007/BF02071878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heidmann T, Oswald R E, Changeux J P. Biochemistry. 1983;22:3112–3127. doi: 10.1021/bi00282a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson D A, Ayres S. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6330–6336. doi: 10.1021/bi960123p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boyd N D, Cohen J B. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4023–4033. doi: 10.1021/bi00313a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sine S M, Taylor P. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:8106–8104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neher E. J Physiol (London) 1983;339:663–678. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pascual J M, Karlin A. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:717–739. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.6.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallagher M J, Chiara D C, Cohen J B. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1514–1522. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.6.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arias H R, McCardy E A, Bayer E Z, Gallagher M J, Blanton M P. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;403:121–131. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tikhonov D B, Zhorov B S. Biophys J. 1998;74:242–255. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77783-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang L M, Catterall W A, Ehrenstein G. J Gen Physiol. 1978;71:397–410. doi: 10.1085/jgp.71.4.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dwyer T M, Adams D J, Hille B. J Gen Physiol. 1980;75:469–492. doi: 10.1085/jgp.75.5.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen B N, Labarca C, Czyzyk L, Davidson N, Lester H A. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:545–572. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villarroel A, Herlitze S, Witzemann V, Koenen M, Sakmann B. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1992;249:317–324. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]