Abstract

Radiolytic protein footprinting with a synchrotron source is used to reveal detailed structural changes that occur in the Ca2+-dependent activation of gelsolin. More than 80 discrete peptides segments within the structure, covering 95% of the sequence in the molecule, were examined by footprinting and mass spectrometry for their solvent accessibility as a function of Ca2+ concentration in solution. Twenty-two of the peptides exhibited detectable oxidation; for seven the oxidation extent was seen to be Ca2+ sensitive. Ca2+titration isotherms monitoring the oxidation within residues 49–72 (within subdomain S1), 121–135 (S1), 162–166 (S2), and 722–748 (S6) indicate a three-state activation process with a intermediate that was populated at a Ca2+ concentration of 1–5 μM that is competent for capping and severing activity. A second structural transition with a midpoint of ≈60–100 μM, where the accessibility of the above four peptides is further increased, is also observed. Tandem mass spectrometry showed that buried residues within the helical “latch” of S6 (including Pro-745) that contact an F-actin-binding site on S2 and buried F-actin-binding residues within S2 (including Phe-163) are unmasked in the submicromolar Ca2+ transition. However, residues within S4 that are part of an extended β-sheet with S6 (including Tyr-453) are revealed only in the subsequent transition at higher Ca2+ concentrations; the disruption of this extended contact between S4 and S6 (and likely the analogous contact between S1 and S3) likely results in an extended structure permitting additional functions consistent with the fully activated gelsolin molecule.

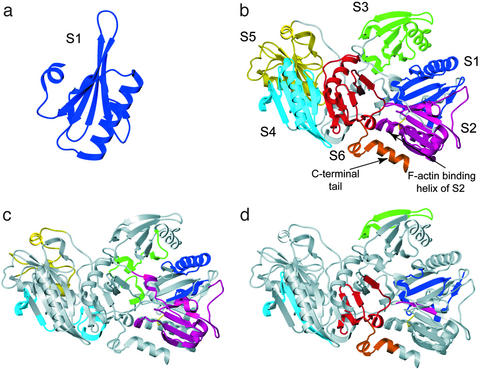

Gelsolin is a Ca2+-dependent actin-regulatory protein composed of six homologous subdomains (denoted S1–S6) that severs actin filaments (F-actin) and caps the fast-growing barbed end with high affinity (1–5). The structure of S1 is organized around a central five-stranded mixed β-sheet sandwiched between a long α-helix running approximately parallel to the strands and a shorter α-helix running approximately perpendicular to the strands (Fig. 1a) (6). This general architecture is shared by all subdomains. The inactive Ca2+-free form of gelsolin exhibits a remarkably compact structure, in which the N-terminal (S1–S3) and C-terminal (S4–S6) halves are joined by a long linker and form an extensive interface (4, 5). Within the N-terminal half, there are considerable intersubdomain contacts (Fig. 1b). Specifically, an extended β-sheet is formed by the individual sheets of S1 and S3, and the extended 30-residue stretch that connects S2 and S3 runs over the central sheet of S1. The C-terminal half displays similar structural features, and the extended β-sheet formed between S4 and S6 is seen in the orientation provided in Fig. 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the structure of the S1 subdomain of gelsolin. (b) Subunit structure of gelsolin, S1 (blue), S2 (magenta), S3 (green), S4 (cyan), S5 (yellow), S6 (red), and C-terminal tail (orange); subdomain linker regions are gray. (c) Peptides identified that were oxidized, but whose oxidation extent did not change as a function of Ca2+. The peptide locations are color coded according to the subdomain where they are found as per b. Peptides found in linker regions are color coded according to the color code of their nearest subdomain. This figure illustrates 15 peptides whose modification rate was Ca2+ insensitive. Shown are peptides 31–34 (S1, blue), 38–45 (S1, blue), 87–115 (S1, blue), 143–150 (S2, magenta), 151–161 (S2, magenta), 173–207 (S2, magenta), 231–250 (S2, magenta), 251–262 (S2–S3 linker, magenta), 342–346 (S3, green), 347–363 (S3, green), 371–386 (S3–S4 linker, green), 393–420 (S3–S4 linker, cyan), 424–438 (S4, cyan), 571–588 (S5, yellow), and 600–210 (S5, yellow). (d) The seven peptides that were Ca2+ sensitive, color coded as per b. Shown are peptides 49–72 (S1, blue), 121–135 (S1, blue), 162–166 (S2, magenta), 276–300 (S3, green), 431–454 (S4, cyan), 652–686 (S6, red), and 722–748 (S6, red, and C-terminal tail, orange).

The N-terminal half of gelsolin severs actin filaments through a mechanism that is thought to involve initial side binding through S2 (7, 8), which facilitates filament severing and barbed end capping by S1. The C-terminal half of gelsolin appears to function as a regulatory domain that senses the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and signals this information to the N-terminal half (9). In addition, the C-terminal half (S4–S6) constitutes a Ca2+-dependent, monomer-binding fragment that competes for the same binding site on actin as S1 (10). The helical tail of S6, termed the “latch” (depicted in orange), interacts in a noncovalent manner with the F-actin-binding helix of S2 (4), making its actin-binding sites inaccessible in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 1b).

Gelsolin is present in both the cytoplasmic and extracellular milieus, being found in a wide range of cell types and in blood plasma (4, 11–13). The intracellular Ca2+ concentration is tightly regulated in the range of 10−7 to 10−5 M, whereas millimolar concentrations are common in plasma. A number of biophysical approaches, including fluorescence (9, 14–18), equilibrium dialysis (19, 20), dynamic light scattering (21), and x-ray crystallography (4, 6, 10), have been used to examine the binding of Ca2+ to gelsolin and the Ca2+-induced structural reorganization associated with its actin-binding and -severing activity (22–24). The occupancy of very-high-affinity sites (Kd < 0.1 μM), likely within S5 or S6, appears to induce a significant conformational reorganization, including the possible release of the S6 latch that sequesters the F-actin-binding site present in S2 (21). Capping activity appears to require higher Ca2+ concentrations (≈1 μM), whereas severing activity appears to require slightly higher concentrations (likely in the few micromolar range) (18). Low-affinity sites (10–200 μM) also exist that are coupled to actin monomer-binding activity (17).

Only modest structural information is available regarding the Ca2+-induced reorganization accompanying gelsolin activation (9). Specifically, a structure of S4–S6 bound to Ca2+ and actin at 3.4-Å resolution shows details of specific rearrangements involving S4 and S6, which are thought to represent steps in the Ca2+ activation process (10). The most dramatic is the disruption of the extended β-sheet between S4 and S6, with S6 rotating away from S4 and moving adjacent to S5; however, it is unclear which of the above Ca2+-binding processes induces this reorganization. There exists a need to develop experimental approaches that directly link Ca2+-binding events with structural rearrangements at the atomic scale.

Radiolytic protein footprinting provides a quantitative approach to monitor changes in surface accessibility of specific amino acid side chains (25). Hydroxyl radicals generated from millisecond exposure of aqueous solutions to unattenuated “white” synchrotron radiation result in the stable oxidative modification of solvent-accessible amino acid side chains (26). The specific extents and sites of oxidative modification are quantified by proteolytic digestion and MS (25, 27). The most reactive residues, which represent the most easily observed experimental probes for this method, include surface-accessible cysteine, methionine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, histidine, proline, and leucine side chains (26). Of the 81 tryptic peptides analyzed for gelsolin (of 85 possible), 22 showed oxidation upon millisecond exposure to the x-ray beam. Of these 22, 5 peptides exhibited a Ca2+-dependent enhancement in oxidation rate, whereas 2 exhibited a Ca2+-dependent protection. These measurements allowed the structural alterations associated with the Ca2+-associated gelsolin activation process to be mapped at the resolution of individual amino acids.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Recombinant human plasma gelsolin was prepared as described by Wen et al. (28). Cacodylic acid sodium salt trihydrate and ethylene glycol bis(2-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) were purchased from Fluka (≥99.0%); CaCl2, from Aldrich (99.99%); Ca2+ indicator Fura-2, from Molecular Probes; and sequencing grade modified trypsin, from Promega. The concentration of gelsolin protein was photometrically determined by using an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 1.4 ml/(mg⋅cm) (29).

Sample Preparations and Experimental Design.

For all experiments, gelsolin was dialyzed against 10 mM sodium cacodylate/0.5 mM EGTA buffer, pH 7.0, at 4°C with three changes. The gelsolin concentration was adjusted to 10 μM for the dose–response experiments and to 2 μM for the Ca2+ titration experiments. For the dose–response experiment in the case of the “Ca2+-free” samples, the gelsolin samples were prepared as described above or a CaCl2 solution was added to a Ca2+ concentration of 0.2 mM. For the Ca2+-dependent isotherms, the Ca2+ concentration was varied between 50 nM and 5 mM with CaCl2. A 5-μl portion of each protein solution was dispensed into a 0.7-ml microcentrifuge tube for radiolysis. All experiments were performed at ambient temperature. The buffer and CaCl2 solutions were prepared by using nanopure-filtered water and stored in plastic vessels. Less than 120 nM contaminating free Ca2+ was measured in 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0, by using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fura-2. The free Ca2+ concentrations for the buffers containing EGTA and/or Ca2+ were calculated by using the computer program WEBMAXC v2.10 (Stanford University, Stanford, CA), which has inputs such as buffer conditions, nucleotide concentration, temperature, and ionic strength (30).

Synchrotron X-Ray Radiolysis and MS.

Radiolysis experiments were performed at Beamline X-28C of the National Synchrotron Light Source at beam currents ranging between 183 and 195 mA according to published procedures (25–27). Irradiated protein solutions were subjected to proteolysis by trypsin at an enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:50 at 37°C for 12 h. A Finnigan (San Jose, CA) liquid chromatography quadrupole (LCQ) ion trap mass spectrometer with an electrospray ion source was used to determine the extent of oxidation in the unmodified proteolytic peptides and their radiolytic products. Digested protein solutions were introduced into the ion source by using an Alliance 2690 Waters (Milford, MA) high-pressure LC system with a Vydac (Hesperia, CA) 1.0 × 150 mm reverse-phase C18 column (27). The fraction of modified peptide was calculated from the ratio of the area under ion signals for the radiolytic products to the sum of the areas for the unoxidized peptides and their radiolytic products. Tandem MS spectra were acquired to identify sites of amino acid side-chain oxidation (25–27).

Side-Chain Solvent-Accessibility Calculation.

The solvent-accessible surface area of the crystal structure of calcium-free equine plasma gelsolin (PDB ID code 1DON) was analyzed by using vadar (Protein Engineering Network of Center of Excellence, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada). Human plasma gelsolin shares ≈95% of its sequence with equine plasma gelsolin.

Data Analysis.

Analysis of the dose–response plots and the fitting isotherms followed our standard procedures (25–27). Duplicate experiments were globally analyzed in each case. The isotherms for each peptide were first normalized to each other at the endpoints to correct for small changes in oxidation extent between the two measurements. Then Ca2+-dependent isotherms were fit to the Hill equation as described in Description of the Fitting Analysis in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. The “transition extent” is plotted on the left-hand y axis, the extent of oxidation on the right-hand y axis. The x axis of the plots reflects the [Ca2+] calculated by using the WEBMAXC v2.10 program (30) and is the Ca2+ concentration available for gelsolin to bind. For the Hill equation to be appropriately applied, the above “calculated” and actual free Ca2+ concentrations must be close. To the extent that gelsolin binds Ca2+ ions, the x axis value will be higher than the actual free Ca2+ concentration. The deviation at a specific calculated Ca2+ concentration depends on the gelsolin concentration, the number of Ca2+ ions bound for each transition, and the transition extent.

Results and Discussion

Footprinting Dose–Response Data Reveal Ca2+-Dependent Activation of Gelsolin.

Plasma gelsolin samples at a concentration of 10 μM buffered in either 200 μM Ca2+ and 0.5 mM EGTA or in the presence of 0.5 mM EGTA (this “Ca2+-free” state is <10 nM Ca2+) were exposed to a synchrotron white beam at the X-28C station for intervals from 0 to 160 msec and subjected to proteolysis (25, 27). The extent of side-chain oxidation for the 22 peptides that exhibited oxidation were analyzed by HPLC–MS and dose–response curves were obtained by plotting the fraction unmodified for each peptide as a function of exposure time. First-order rate constants were derived from this analysis as previously described (25–27). The observation of first-order processes for the loss of unmodified fraction extrapolated to zero fraction modified indicates that the native gelsolin structure is probed in these experiments (27).

Modification rate data for 10 of the 22 reactive peptides are shown in Table 1. The behavior of the 22 peptides that exhibited oxidation and the behavior of the 59 peptides that did not exhibit oxidation (data not shown) were entirely consistent with the results of surface-accessibility calculations on the native, calcium-free, gelsolin molecule; e.g., the peptides lacking residues that were both accessible and modifiable did not exhibit oxidation. A typical result of this type includes peptide 162–166, which was found to be unreactive at low Ca2+ concentration; in this case modifiable residues are located within the peptide but they are entirely buried (Table 1).

Table 1.

Rate constants for the oxidation of gelsolin peptides

| Domain | Peptide | Sequence | Oxidized amino acid(s) | Rate of modification at reactive residue(s), sec−1

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mM Ca2+ | 0.2 mM Ca2+ | ||||

| S1 | 49–72 | FDLVPVPTNLYGDFFTGDAYVILK | Phe-49, Tyr-59 | 1.47 ± 0.09 | 2.24 ± 0.13 |

| 109060457370600 | |||||

| S1 | 121–135 | EVQGFESATFLGYFK | Phe-125 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.98 ± 0.10 |

| 760131211 | |||||

| S2 | 151–161 | HVVPNEVVVQR | Pro-154 | 0.80 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.04 |

| 1067 | |||||

| S2 | 162–166 | LFQVK | — | — | 0.35 ± 0.05 |

| 00 | |||||

| S2 | 231–250 | VHVSEEGTEPEAMLQVLGPK | Leu-244, Pro-249 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.05 |

| 311632123 | |||||

| S3 | 276–300 | VSNGAGTMSVSLVADENPFAQGALK | Met-283 | 16.11 ± 1.80 | 2.07 ± 0.12 |

| 3742835 | |||||

| S4 | 431–454 | VPVDPATYGQFYGGDSYIILYNYR | Pro-432, Pro-435, | 1.05 ± 0.10 | 1.74 ± 0.19 |

| 89944513311405 | Tyr-438, Tyr-442 | ||||

| S5 | 571–588 | TPSAAYLWVGTGASEAEK | Pro-572, Tyr-576 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.08 |

| 911930 | |||||

| S6 | 652–686 | FVIEEVPGELMQEDLATDDVMLLDTWDQVFVWVGK | Met-662, Trp-677 | 78.35 ± 40.10 | 7.22 ± 2.26 |

| 101387201006650 | |||||

| S6 | 722–748 | QGFEPPSFVGWFLGWDDDYWSVDPLDR | Phe-724, Leu-734, | 1.91 ± 0.15 | 3.26 ± 0.20 |

| 101001120104102819246 | Tyr-740 | ||||

The first and second columns show the subdomain and amino acid range defining the peptide, respectively. The third column lists the amino acid sequence in the one-letter code with the potentially modifiable residues in boldface and side-chain accessible surface area (Å2) for these residues in the inactive gelsolin structure printed immediately below.

Fifteen peptides that exhibited oxidation were observed to have oxidation rates that were Ca2+ independent (i.e., they were identical within the experimental errors in the presence of either 200 μM Ca2+ or EGTA); data for three are shown in Table 1. In addition, these 15 peptides are displayed in Fig. 1c. The data indicate that no changes occur in S5 and that minimal changes occur in the S2 β-sheet as a function of Ca2+ concentration.

In Fig. 1d, we illustrate the locations of the five peptides in the gelsolin structure that showed increased rates of oxidation in the presence of Ca2+. Peptide 162–166 (part of the F-actin-binding site on S2) exhibited a significant increase in oxidation rate upon Ca2+ binding (magenta in Fig. 1d). Unfortunately, the region including residues 209–230 (the other F-actin-binding site on S2, including the long α-helix) could not be analyzed because of the absence of any modifiable amino acid. The four other peptides that exhibited Ca2+-dependent increases in oxidation are located in S1 (blue), S4 (cyan), and S6 (red, and orange for the helical tail). The observed increases in oxidation rate ranged from 40% to 70%. Two additional peptides located in subdomains S3 and S6 showed dramatic decreases in oxidation extent in the presence of 200 μM Ca2+ (Fig. 1d). For example, peptide 276–300 in S3 showed an 87% decrease in reactivity, whereas peptide 652–686 in S6 showed a decrease of ≈90%.

Equilibrium Intermediates in the Ca2+-Dependent Activation of Gelsolin.

The dose–response data in Table 1 are consistent with a Ca2+-dependent conformational rearrangement that results in increased accessibility of specific protein segments and protection of others. Furthermore, these data identify a specific dose regime in which the Ca2+-dependent oxidation of many of the reactive residues could be examined; at 80-msec exposure the loss of the unmodified fraction is still first order, except for peptides 276–300 and 652–686. For these peptides, the oxidation is first-order only at ≤40-msec exposure, such that only data on samples exposed for ≤40 msec were used to generate the rate constants of Table 1. Experiments were performed with 2 μM gelsolin that had been preincubated at free Ca2+ concentrations ranging from 50 nM to 5 mM as described in Materials and Methods. The samples were then exposed to the x-ray beam for 80 msec. In these experiments, the fraction oxidized was calculated at each Ca2+ concentration and plotted (Fig. 2). The peptide segments analyzed in Table 1 (excluding peptides 276–300 and 652–686) are illustrated, and data from two separate experiments are shown in each case. In Fig. 2f, the data from three of the peptides that did not exhibit Ca2+-dependent changes in oxidation rate (Table 1) are shown.

Figure 2.

Ca2+ titration isotherms indicating changes in oxidation extent for specific peptides after exposure of gelsolin to the x-ray beam for 80 msec. (a–e) The percent oxidized peptide is shown on the right side of the y axis; on the left side, the transition extent is indicated. The solid lines represent the fitting of the curves as described in the text. (f) Oxidized peptides within gelsolin from Table 1 that show no changes in oxidation upon titration by Ca2+. The percent oxidized peptide is shown on the right and left sides.

The five peptides that exhibited Ca2+-dependent increases in oxidation rate (Table 1) exhibit complex changes in oxidation extent as a function of Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 2). The Ca2+ titration isotherms obtained for protein regions 49–72 (S1), 121–135 (C terminus of S1), 162–166 (S2), and 722–748 (S6 and S6 tail helix) are sensitive to submicromolar Ca2+-binding events that saturate at ≈10 μM Ca+2 and exhibit a distinct second transition saturating above ≈0.5 mM Ca2+. Thus, these isotherms exhibit a distinct intermediate that is significantly populated in the 1–10 μM Ca+2 concentration range. In contrast, the peptide composed of residues 431–454 (S4) showed a single transition with a midpoint of ≈0.1 mM Ca2+. The titrations in Fig. 2 a–e were individually fit to either a single (e) or the sum of two (a–d) Hill equations based on the observed number of transitions. Because the high-affinity sites are known to have Kd values in the submicromolar range whereas the gelsolin concentration is 2 μM in these experiments, the fitting parameters reported by the Hill analysis for the transition seen at low Ca+2 concentrations are not valid, because the x axis represents added Ca2+ not free Ca2+. However, the plateau region should properly reflect the stoichiometry of addition.

Biochemical data indicate that gelsolin can bind multiple Ca2+ ions (19, 20), whereas recent crystallographic data of the S4–S6/actin complex suggest that six high-affinity sites (type 2) and two low-affinity sites (type 1) may exist (31). At 2 μM gelsolin, the occupancy of ≈6 high-affinity Ca2+-binding sites should be complete at an added Ca+2 concentration of ≈10–15 μM. This estimate is consistent with the observed data for the first transitions. Above 10–15 μM concentration, during the second phase transition, the x axis more reasonably represents the free Ca2+ concentration, and the Hill parameters derived from the associated fits are reliable. Thus in Table 2 we report the apparent Kd of the isotherms for the activation process only for the lower-affinity sites, taken as the midpoint of the transition, and the apparent cooperativity (Hill coefficient), for the five peptides. This fitting analysis provides midpoints that are in a tight range from ≈0.06 to ≈0.1 mM. The isotherms of peptide 49–72 and peptide 722–748 indicate similar transitions with Hill coefficients of 1.5 ± 0.1. The observed binding of Ca2+, clearly seen for two of these peptides, is moderately cooperative, consistent with previous fluorescence-based studies of activation (18). In contrast, the transition for peptide 431–454 is noncooperative. The data for peptides 121–135 and 162–166 have a larger error and it cannot be determined whether they are modestly cooperative or noncooperative.

Table 2.

Midpoint Ca2+ concentrations and Hill coefficients for the low-affinity binding sites

| Proteolytic peptide | Kd, μM (2 μM gelsolin) | Hill coefficient (2 μM gelsolin) |

|---|---|---|

| 49–72 | 97.3 ± 5.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| 121–135 | 73.0 ± 22.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| 162–166 | 60.4 ± 17.8 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 431–454 | 81.6 ± 7.4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| 722–748 | 88.4 ± 6.7 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

The data of Fig. 2 were fit as described in the text. The Kd of the Ca2+ activation, taken as the midpoint of the transition, and the apparent cooperativity (Hill coefficients) for the low-affinity transitions for the five peptides are given. Titration isotherms were obtained for protein regions after exposure to the x-ray beam of gelsolin (2 μM) for 80 msec.

The results provide clear evidence for a three-state Ca2+-induced activation process. State 1 corresponds to the “Ca+2-free” form, state 2 is the intermediate observed in these studies that involves some unlatching of the structure, and state 3 is the Ca2+-saturated fully activated form. The transition between states 1 and 2 occurs at submicromolar concentrations, which is in a good agreement with the previous biochemical studies (1, 9, 15, 19, 21), and is accompanied by the binding of multiple Ca2+ ions. The transition between states 2 and 3 is mediated by occupancy of lower-affinity binding sites and is accompanied by the binding of two or three additional Ca2+ ions (see Description of the Number of Ca2+ Ions Bound to Gelsolin in the Second Transition in Supporting Text).

Visualizing the Structural Biology of Gelsolin Activation.

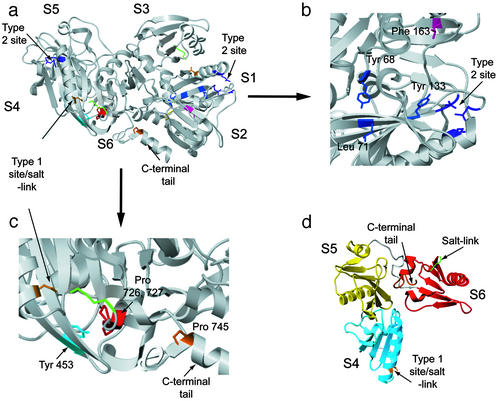

Tandem MS was used to identify the specific side chains that are sensitive to oxidation, thus allowing for a correlation of the isotherms with the structural biology of activation. Table 1 (and Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) identifies residues modified in the absence of Ca2+. In the presence of Ca2+, the oxidation of eight additional amino acids was detected, including Tyr-68 and Leu-71 in the β-sheet of S1 (blue); Tyr-133 at the C terminus of S1 (blue); Phe-163, on an F-actin-binding segment of S2 (magenta); Tyr-453 in the β-sheet of S4 (cyan); Pro-726 and Pro-727 in S6 (red); and Pro-745 in the C-terminal tail (orange) (Fig. 3 b and c). These residues are partially or entirely buried in the inactive gelsolin structure. On binding Ca2+, the oxidation rate of these side chains, as well as increases in the oxidation rate of initially accessible residues, contributes to the total increase in oxidation rate observed for peptides 49–72, 121–135, 162–166, 431–454, and 722–748. Fig. 1d illustrates the locations of these regions within the gelsolin structure.

Figure 3.

(a) Subunit structure of gelsolin. The type 2 Ca2+-binding sites in S1 and S4 are colored purple. The buried residues that are revealed in the presence of Ca2+ are color coded by subunit placement and are described in the text. The type 1 Ca2+-binding site in S4 is also shown. Two of the residues from S4 are shown in gold. A third residue from S6, which forms a salt link between the subunits, is shown in green. (b) A close-up of the S1 type 2 site with the adjacent reactive residues labeled. (c) A close-up of the S4 type 1 site with the reactive residues labeled. (d) Structure of the activated C-terminal half of gelsolin. The residues that formed the salt link between S4 and S6 in the inactive form are indicated.

Crystallography has provided direct evidence for type 1 (low-affinity) and type 2 (high-affinity) classes of Ca2+ site. A type 1 site (observed in the crystallographic structure of Ca2+-activated S4–S6) includes three ligands from gelsolin subdomain S4 and a fourth ligand from actin (Fig. 3a) (10). One of the residues coordinating Ca2+ in the S4 type 1 site is Asp-487 (Fig. 3c, gold). However, in inactive gelsolin, Asp-487 forms a salt bridge with Lys-721 within S6 (Fig. 3 a and c, green), which stabilizes the extended β-sheet. An analogous type 1 site is likely to exist in the N-terminal half of the molecule. In this case, a ligand located within subdomain S1 that coordinates Ca2+ in the activated state (Asp-109) stabilizes the extended β-sheet of S1/S3 in inactive gelsolin by formation of a salt link (to Lys-319) (4). Two high-affinity (type 2) sites have also been identified; they are shown in purple in Fig. 3 a and b. Recently, other high-affinity sites have been observed in S5 and S6 (31). These sites and the type 2 sites in S1 and S4 (shown in Fig. 3a) are likely occupied during the first observed transition isotherm in Fig. 2. No peptides within S5 are detected to change their modification rate as a function of Ca2+ concentration. However, three residues within S6, including Pro-726, -727, and -745 (Fig. 3a) become exposed upon Ca2+ binding, suggesting that the helical latch is released in the first transition coincident with the occupancy of a high-affinity Ca2+-binding site in S6 (31).

One of the type 2 sites includes residues Gly-65, Asp-66, and Glu-97 from S1 and Val-145 from S2. Note that the directly adjacent residues Tyr-68 and Leu-71, which are entirely buried in inactive gelsolin (0 Å2, Table 1) are oxidized upon Ca2+ binding. Although the type 2 binding site is mostly preorganized, residue 145 must rotate 180o to bind Ca2+ (4). This residue is within an extended loop (Fig. 3b) that contacts one of the β-strands of S2. Importantly, Phe-163, which is located within this strand (Fig. 3b), is part of the F-actin-binding surface in S2. Phe-163 is entirely buried in inactive gelsolin (Table 1); its oxidation with added Ca2+ indicates that the S2 actin-binding helix (seen immediately to the left of Phe-163 in Fig. 3b) must move up and out in response to Ca2+ binding. The enhanced oxidation of the numerous residues within S1 and S2 indicates that the structural reorganization associated with activation upon latch release may be extensive, and may be coupled to both the release of the S6 latch and the formation and occupancy of the type 2 site in S1. The type 2 site within S4 has three ligands from S4 and one from a loop of S5 (analogous to the S1 loop described above, Fig. 3a). However, none of the many probe sites within S4 or S5 change their modification rate upon submicromolar Ca2+ binding and only a single peptide within S4 (residues 431–454) exhibits Ca2+-responsive oxidation (Table 2 and Fig. 2). These observations suggest a different role for the C-terminal half of the molecule in the activation process compared with the N-terminal half composed of subdomains S1–S3.

As the Ca2+ concentration is increased above 0.1 mM, the type 1 Ca2+ sites in S1 and S4 are expected to become occupied. Binding at these sites is incompatible with salt links that stabilize the extended β-sheet structures in S1–S3 and S4–S6 (Fig. 3 c and d). Residue Tyr-453, which is buried in inactive gelsolin, is located in the S4 β-sheet that contacts S6 (Fig. 3c, cyan). This extended β-sheet is fully disrupted upon Ca2+-dependent actin binding; the S6 subdomain moves away from S4, making new contacts with S5, and in addition the C-terminal latch loses its helical structure (Fig. 3d). The observation that peptide 431–454 experiences no change in oxidation until the Ca2+ concentration exceeds 10 μM indicates that the S4–S6 interface is intact in the intermediate. This interface is then disrupted in a noncooperative transition coincident with the occupancy of the type 1 site within S4. An analogous disruption of the S1–S3 interface when its type 1 site is occupied may also occur. Consistent with such changes is the observation of two protections as the Ca2+ concentration is increased; these protected sites are located within S3 and S6. For Met-662 of peptide 652–686 within S6, a comparison of the native gelsolin structure in the absence of Ca2+ (4) to the Ca2+-activated structure of the S4–S6 subdomains (10) shows a significant protection of this residue attributable to the rearrangement of S6 described above. The oxidation data for peptide 652–686 seen in Table 1 are entirely consistent with this rearrangement. The protection observed for peptide 276–300 within S3 may be due to a similar rearrangement that disrupts the S1–S3 extended β-sheet and results in docking of S3 residues with S2.

The generalized opening of the gelsolin structure, caused by the disruption of the extended β-sheets, could easily provide a structural explanation for the rough coincidence of the ≈0.1 mM transition observed for all five Ca2+-sensitive peptides. This model of activation also could explain the increased depolymerization activity at higher Ca2+. With the unlatching of the F-actin-binding site at submicromolar concentrations, gelsolin is made competent for severing and capping, but at a modest level of activity. This mechanism implies a tight structural regulation of the intracellular function where Ca2+ concentrations do not exceed 10 μM. At higher concentrations, as in plasma, the molecule opens further as the extended β-sheet contacts are disrupted and the severing and capping activities are increased. In this state, the actin monomer-binding sites are revealed as well, consistent with gelsolin's actin filament scavenging role in responding to cellular death (13).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grants P41-EB-01979 (to M.R.C.), R33-CA-84713 (to M.R.C.), and R01-GM-53807 (to S.C.A.). The National Synchrotron Light Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Division of Materials Sciences.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Yin H L, Stossel T P. Nature. 1979;281:583–586. doi: 10.1038/281583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norberg R, Thorstensson R, Utter G, Fagraeus A F. Eur J Biochem. 1979;100:575–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb04204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janmey P A, Stossel T P. Nature. 1987;325:362–364. doi: 10.1038/325362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtnick L D, Koepf E K, Grimes J, Jones E Y, Stuart D I, McLauqhlin P J, Robinson R C. Cell. 1997;90:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwiatkowski D J, Stossel T P, Orkin S H, Mole J E, Colten H R, Yin H L. Nature. 1986;323:455–458. doi: 10.1038/323455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin P J, Gooch J T, Mannherz H G, Weeds A G. Nature. 1993;364:685–692. doi: 10.1038/364685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan J, Hwo S. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1439–1446. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaponnier C, Janmey P A, Yin H L. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1473–1481. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin K-M, Mejillano M, Yin H L. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27746–27752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson R C, Mejillano M, Le V P, Burtnick L D, Yin H L, Choe S. Science. 1999;286:1939–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin H. BioEssays. 1987;7:176–179. doi: 10.1002/bies.950070409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddad J G, Harper K D, Guoth M, Pietra G G, Sanger S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1381–1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasconcellos C A, Lind S E. Blood. 1993;82:3648–3657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilhoffer M C, Gerard D. Biochemistry. 1985;24:5653–5660. doi: 10.1021/bi00341a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinosian H J, Newman J, Lincoln B, Selden L A, Gershman L C, Estes J E. Biophys J. 1998;75:3101–3109. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77751-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allen P G, Janmey P A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32916–32923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ditsch A, Wegner A. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:512–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0512k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gremm D, Wegner A. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:330–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pope B, Maciver S, Weeds A G. Biochemistry. 1995;34:1583–1588. doi: 10.1021/bi00005a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weeds A G, Gooch J, Pope B J, Harris H E. Eur J Biochem. 1986;161:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope B J, Gooch J T, Weeds A G. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15848–15855. doi: 10.1021/bi972192p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellweg T, Hinssen H, Elmer W. Biophys J. 1993;65:799–805. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koepf E K, Burtnick L D. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:713–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Way M, Gooch J, Pope B, Weeds A. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:593–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiselar J G, Maleknia S D, Sullivan M, Downard K M, Chance M R. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:101–114. doi: 10.1080/09553000110094805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maleknia S D, Brenowitz M, Chance M R. Anal Chem. 1999;71:3965–3973. doi: 10.1021/ac990500e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan J-Q, Vorobiev S, Almo S C, Chance M R. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5765–5775. doi: 10.1021/bi0121104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen D, Corina C, Chow E P, Miller S, Janmey P A, Pepinsky R B. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9700–9709. doi: 10.1021/bi960920n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz Silva B E, Burtnick L D. Biochem Cell Biol. 1990;68:796–800. doi: 10.1139/o90-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bers D, Patton C, Nuccitelli R. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;40:3–29. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choe H, Burtnick L D, Mejillano M, Yin H L, Robinson R C, Choe S. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.