Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Several lines of evidence strongly implicate mitochondrial dysfunction as a major causative factor in PD, although the molecular mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction are poorly understood. Recently, loss-of-function mutations in the parkin gene, which encodes a ubiquitin-protein ligase, were found to underlie a familial form of PD known as autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism (AR-JP). To gain insight into the molecular mechanism responsible for selective cell death in AR-JP, we have created a Drosophila model of this disorder. Drosophila parkin null mutants exhibit reduced lifespan, locomotor defects, and male sterility. The locomotor defects derive from apoptotic cell death of muscle subsets, whereas the male sterile phenotype derives from a spermatid individualization defect at a late stage of spermatogenesis. Mitochondrial pathology is the earliest manifestation of muscle degeneration and a prominent characteristic of individualizing spermatids in parkin mutants. These results indicate that the tissue-specific phenotypes observed in Drosophila parkin mutants result from mitochondrial dysfunction and raise the possibility that similar mitochondrial impairment triggers the selective cell loss observed in AR-JP.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the accumulation of proteinaceous intraneuronal inclusions known as Lewy bodies. Little is known of the molecular mechanisms responsible for loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD; however, evidence suggests that environmental and genetic factors both play contributing roles (1–3). Although only a few of the factors contributing to this disorder have currently been identified, significant insight into the mechanism of neuronal death in PD has come from studies of the PD-inducing compound 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+). MPP+ is a specific toxin of dopaminergic neurons that induces cell death by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I (4–6). This finding led to the identification of other mitochondrial complex I inhibitors that trigger death of dopaminergic neurons (7, 8), and prompted studies of mitochondrial integrity in individuals with idiopathic PD (9–13). These studies revealed a correlation between PD and mitochondrial dysfunction, and together with the studies of mitochondrial toxins, provide strong support for mitochondrial dysfunction as a major component of PD.

Although mitochondrial dysfunction appears to be a prominent feature of idiopathic PD, the molecular mechanisms responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction remain largely unknown. Insight into the molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in PD is beginning to emerge from the identification of loci responsible for rare monogenic forms of this disorder. One of the genes identified from this work is parkin. Loss-of-function mutations in parkin result in an early onset form of PD known as autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism (AR-JP) (14). AR-JP patients display many of the clinical features of idiopathic PD; however, most cases identified lack Lewy body pathology. This observation has led to the suggestion that Parkin may be required for Lewy body formation, or alternatively, that dopaminergic neuron loss in idiopathic PD and AR-JP individuals proceeds through distinct mechanisms.

The parkin gene encodes a polypeptide with an N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain, two carboxy-terminal ring-finger motifs, and an in-between ring-finger (IBR) domain. Recent studies demonstrate that Parkin functions as an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, a common function of proteins with ring domains (15–17). E3 ubiquitin protein ligases act in concert with ubiquitin-activating (E1) and ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes to confer substrate specificity in the ubiquitination pathway. The finding that Parkin functions as a ubiquitin protein ligase indicates that failure to label specific cellular targets with ubiquitin is responsible for dopaminergic neuron loss in AR-JP. Experiments premised on this hypothesis have led to the identification of several potential cellular targets of Parkin, including components of the Lewy body inclusions found in idiopathic PD (17–20). However, lack of an animal model of AR-JP has precluded a direct test of the relevance of these Parkin substrates to dopaminergic neuron loss.

To further explore the biological role of Parkin, we have used a mutational approach to inactivate a highly conserved Drosophila parkin ortholog. Flies bearing null alleles of parkin are viable but exhibit reduced longevity, male sterility, and flight and climbing defects. The male sterile phenotype results from a defect in spermatogenesis, whereas the locomotor phenotypes result from apoptotic muscle degeneration. Mitochondrial structural alterations are prominent features of both the germ line and muscle pathology. These results raise the possibility that mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis underlie dopaminergic neuron loss in AR-JP. Further, these findings suggest a mechanistic link between AR-JP and the more common form of idiopathic PD.

Methods

Molecular Genetics.

DNA sequences encoding the Drosophila parkin ortholog were identified by searching the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project Database (www.fruitfly.org/blast) using a human Parkin polypeptide query sequence (NP_004553). A cDNA clone identified from this analysis (SD01679) was fully sequenced and this sequence was compared with the corresponding genomic DNA sequence to identify splice junctions in the parkin gene. The predicted Parkin polypeptide sequence was aligned to human Parkin by using the clustalw algorithm.

parkin mutants were generated by inducing transposition of the EP(3)3515 P element insertion using an established procedure (http://engels.genetics.wisc.edu/Pelements/index.html). To identify P element insertions in parkin, genomic DNA was obtained from the offspring of ≈5,500 flies and subjected to multiplex PCR analysis with a primer specific to the P element terminal repeat sequence and a pool of primers corresponding to sequences within the parkin gene. This analysis led to the recovery of a single line, parkEP(3)LA1, bearing an insertion 71 bp upstream of the parkin start codon. This chromosome was used to generate imprecise excision alleles of parkin by using standard procedures (22). Deletion breakpoints of the imprecise excision alleles were determined by sequencing. Ethyl methanesulfonate alleles of parkin were identified by screening a collection of homozygous viable male sterile stocks, previously identified by B. Wakimoto, D. Lindsley, and C. Herrera, from a collection established by E. Koundakjian, R. Hardy, and D. Cowen in the laboratory of C. Zuker (23), for failure to complement the park25 allele.

The parkin cDNA clone SD01679 was used to generate transgenic lines after altering a nucleotide sequence polymorphism at codon 240 of this cDNA to correspond to the parkin amino acid sequence predicted from sequence deposited in the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project database and consistent with our laboratory strains. The parkin coding sequence from this modified cDNA was amplified by using PCR primers bearing sequence changes designed to improve translation, and to introduce restriction sites for cloning purposes. The product was ligated into the P{UAST} vector (24), sequenced to ensure the integrity of the parkin coding sequence, and introduced into the Drosophila germ line by using standard procedures.

Northern blot analysis was performed by using 1.5 μg poly(A)+ RNA (CLONTECH) per lane with standard procedures.

Behavioral Assays.

Longevity assays were conducted at 25°C. Flies (0–24 h old) were collected and transferred to new vials every 2–3 days. The number of dead flies was recorded when transferring. Longevity experiments were performed in triplicate for each genotype. Statistical significance was calculated with a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test.

Flight tests were performed by using an apparatus described by Benzer (25) with minor modifications. An acetate sheet was divided into five equal parts, coated with vacuum grease, and inserted into a 1-liter graduated cylinder. To perform flight tests, 1- to 2-day-old flies were dispensed into the apparatus by gently tapping vials containing 20 flies into a funnel placed on top of the graduated cylinder. Flies became stuck to the sheet where they alighted. The sheet was removed and the number of flies was counted in each of the five regions. The flight index was calculated as the weighted average of the region into which the flies landed divided by four times the number of flies in the assay. At least 100 flies of each genotype were tested.

Climbing assays were performed by using a countercurrent apparatus developed initially for phototaxis experiments (26). Twenty to thirty flies were placed into the first chamber, tapped to the bottom, then given 30 sec to climb a distance of 10 cm. Flies that successfully climbed 10 cm or beyond in 30 sec were then shifted to a new chamber, and both sets of flies were given another opportunity to climb the 10-cm distance. This procedure was repeated a total of five times. After five trials, the number of flies in each chamber were counted. The climbing index was calculated in the same manner as the flight index (see above). At least 60 flies were used for each genotype tested.

Sectioning, Staining, and Microscopy.

Histologic sections of muscle and brain were prepared from wax-embedded material. Flies were fixed in 4% formalin, dehydrated, and infiltrated with paraffin. Frontal sections were cut at 4-μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or immunostained with a polyclonal antibody to tyrosine hydroxylase (1:500, Chemicon). Dorsomedial dopamine neurons were counted in at least eight hemibrains per genotype and time point (27).

Tissues for electron microscopy were prepared by dissecting testes from 6-h-old males, thoraces from 1- to 2-day-old adults, or aged pupae, in 2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% gluteraldehyde, and fixed overnight. After rinsing in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer with 1% tannic acid, samples were postfixed in 1:1 2% OsO4 and 0.2 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h. Samples were rinsed, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and embedded by using Epon.

Results

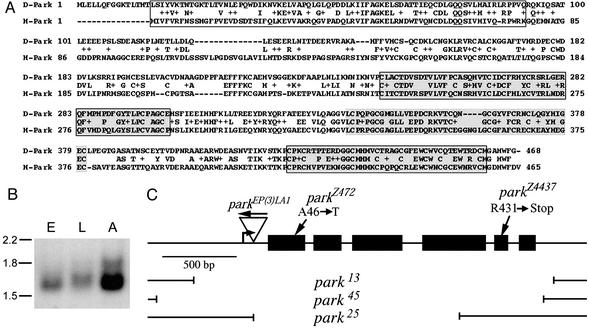

To identify a Drosophila homolog of the parkin gene, the human Parkin protein sequence was used to query a six-way translation of the Drosophila genome sequence. From this search, a single gene was identified that encodes a polypeptide of 468 aa exhibiting 42% amino acid identity and 59% similarity overall with human Parkin (Fig. 1A). This gene is the only one in the Drosophila genome that encodes a polypeptide bearing a ubiquitin-like domain, ring-finger domains, and an IBR domain, indicating that it represents the Drosophila parkin ortholog. Northern blot analysis using poly(A)+ RNA from embryos, larvae, and adults detected parkin transcripts at all developmental stages with particularly high abundance in adults (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence, expression pattern, and mutant alleles of parkin. (A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Drosophila Parkin (D-Park) with human Parkin (H-Park). The N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain (boxed), RING finger domains (boxed and shaded), and In-Between Ring domain (shaded) are designated. (B) Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA obtained from wild-type embryos (E), third-instar larvae (L), and adults (A) using a parkin-specific probe. Size units are in kilobases. Adult flies appear to express a larger, less abundant parkin transcript in addition to the major transcript of 1.7 kb. (C) Molecular map of the parkin transcript showing the parkEP(3)LA1 insertion, the breakpoints of the three parkin deletion alleles described in this work, and the locations of the parkin point mutations. The bent arrow represents the predicted transcription initiation site of parkin and the black boxes designate Parkin protein-coding sequences. The arrow above the parkEP(3)LA1 insertion designates the orientation of this P element.

To generate a disruption of the parkin gene, a transposon mutagenesis screen was conducted by using a P element mapping close to parkin. This strategy yielded a single line, designated parkEP(3)LA1, bearing an insertion 71 bp upstream from the parkin start codon (Fig. 1C). To generate more severe alleles of parkin, the parkEP(3)LA1 insertion was mobilized with transposase under conditions favoring the creation of coincident deletions extending from the insertion locus (22). A large collection of deletion alleles were recovered from this screen, including several that remove all of the parkin coding sequence and thus represent null alleles of parkin (Fig. 1C). This work also yielded a chromosome bearing a precise excision of parkEP(3)LA1, which was maintained for use as a control chromosome (designated parkrvA) in our studies.

Flies bearing any of the parkin null alleles in trans to the Df(3L)Pc-MK deletion chromosome, which removes the parkin gene, are viable through the adult stage of development but exhibit a slight developmental delay, typically eclosing a day later than controls, and show significantly reduced longevity (P < 0.0001). parkin null flies have an average lifespan of 27 days, with none able to exceed 50 days of age, whereas flies bearing the parkrvA precise excision chromosome in trans to Df(3L)Pc-MK have a mean lifespan of 39 days and can survive up to 75 days.

Female parkin mutants are fertile and produce normal offspring, however, males are completely sterile. This finding allowed us to screen a collection of ≈1,100 ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized homozygous viable male sterile lines for additional parkin mutations generated independently from our deletion alleles. Sequencing the parkin gene from two of the mutants recovered from this screen revealed missense and premature stop codon mutations (Fig. 1C), verifying that the male sterile phenotype results from loss of parkin function.

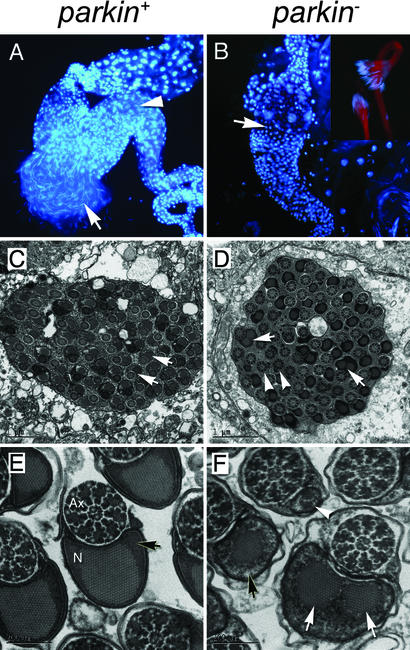

Analysis of testes from homozygous or transheterozygous parkin mutants indicates that the male sterile phenotype derives from a late defect in spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis appears to proceed normally in parkin mutants until the individualization stage, at which point a 64-cell germ-line cyst that normally separates into mature sperm cells fails to do so, resulting in an absence of mature sperm cells in the seminal vesicle (Fig. 2). Ultrastructural analysis of developing spermatids in parkin mutants revealed structural irregularities in the sperm tails. Mature sperm tails usually consist of a flagellar axoneme, with a 9 + 2 arrangement of microtubules, and a specialized mitochondrial derivative known as the Nebenkern (Fig. 2 C and E). Although the axoneme in parkin mutants appears normal, Nebenkern integrity is severely disrupted; some spermatids have multiple Nebenkern, whereas others have only an extremely diminished component (Fig. 2 D and F). Additionally, the electron density of the Nebenkern outer matrix is significantly diminished with respect to wild type (Fig. 2 E and F). These results suggest that defective Nebenkern formation and/or function may underlie the spermatid individualization failure of parkin mutants.

Figure 2.

parkin mutants manifest a spermatid individualization defect associated with abnormal mitochondrial derivatives. (A) parkin+ testes reveal the presence of many individual sperm released from a ruptured testis (arrow). The long, thin nuclei of mature spermatozoa can also be seen inside the seminal vesicle (arrowhead). Round nuclei correspond to cells of the testis sheath. (B) Analysis of parkin− testes reveals an absence of mature sperm in the seminal vesicle (arrow). However, mature spermatids are formed (Inset) but fail to individualize and remain as a syncytial bundle. (C) Ultrastructural analysis of a cross section through a wild-type late-stage 64-cell cyst showing the regular arrangement of developing spermatids (arrows). (E) Higher magnification cross sections of mature spermatozoa after individualization showing the axoneme (Ax) and a mitochondrial derivative, the Nebenkern (N), tightly enclosed in a membrane. Note the paracrystalline structure in the Nebenkern surrounded by uniform electron-dense material (arrow). In parkin− mutants (D and F) the axonemes have a highly regular and well-formed appearance, but the Nebenkern display an abnormal distribution. Some spermatids are associated with multiple large Nebenkern (arrows), whereas others have a significantly diminished Nebenkern (arrowheads). In addition, the electron-dense matrix surrounding the paracrystalline structure of the Nebenkern appears diffuse (F, black arrow, compare with E). (A and B) Dissected testes were stained with DAPI to mark nuclei. (B Inset) Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin was used to highlight spermatid tails. Genotypes; parkin+: parkrvA/Df(3L)Pc-MK, parkin−: park13/Df(3L)Pc-MK.

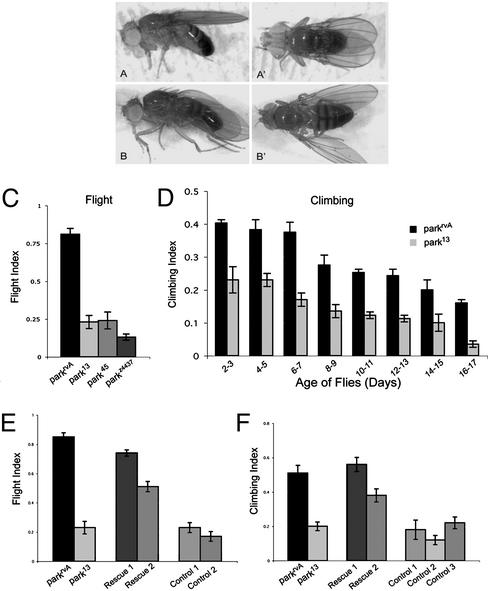

In addition to reduced longevity and male sterility, all of the parkin null alleles, as well as those recovered on the basis of the male sterile phenotype, confer a partially penetrant downturned wing phenotype as homozygotes or as transheterozygotes with the Df(3L)Pc-MK chromosome (Fig. 3 A and B). The penetrance of this phenotype increases with age; ≈40% of newly eclosed flies exhibit abnormal wing posture, whereas by 10 days of age more than 70% of the parkin mutants display this phenotype. This finding prompted us to assay locomotor ability of the parkin mutants. These analyses revealed severe defects in both flight and climbing ability in parkin mutants (Fig. 3 C and D). Both phenotypes were also manifest in parkin mutants with normal wing posture (data not shown). The climbing decay rate was similar in parkin mutants and wild-type flies, indicating that parkin mutants begin adult life with a reduced climbing ability.

Figure 3.

Parkin function is required in mesoderm for normal wing posture, flight, and locomotion. (A and A′) Wing posture in 1-day-old control flies (parkrvA/Df(3L)Pc-MK) and (B and B′) age-matched parkin mutants (park25/Df(3L)Pc-MK) showing the downturned wing phenotype of parkin mutants. (C and D) parkin mutants exhibit impaired flight and climbing ability relative to control flies (see Methods for details). All flies tested were transheterozygous for the Df(3L)Pc-MK deletion and the parkin allele indicated. (E and F) Ectopic expression of parkin in mesoderm with the 24B-GAL4 (24) or Dmef2-GAL4 (21) driver restores flight and climbing ability in parkin mutants. All flies tested were transheterozygous for the Df(3L)Pc-MK deletion and the parkin allele indicated. Genotypes: Rescue 1: w; UAS-park/+; park13/24B-GAL4, Df; Rescue 2: w; UAS-park/+; park13/Dmef2-GAL4, Df; Control 1: w; park13/Dmef2-GAL4, Df; Control 2, w; park13/24B-GAL4, Df; Control 3: w; UAS-park/+; park13/Df. Error bars indicate the SEM.

To address the origin of the locomotion defects in parkin mutants, the UAS/GAL4 system (24) was used to express parkin in defined tissues. Two GAL4 lines that drive parkin expression in mesoderm were found to rescue the wing posture, flight, and climbing phenotypes of parkin mutants to wild-type or near wild-type levels (Fig. 3 E and F), demonstrating that Parkin function is required in the musculature.

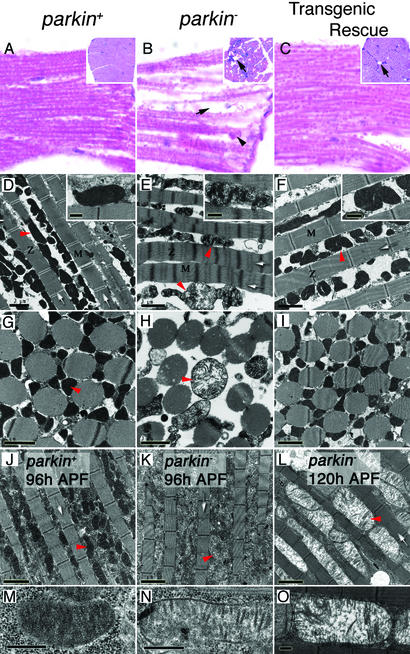

Histological analysis of the major flight muscles [the indirect flight muscles (IFMs)] from parkin mutants revealed severe disruption of muscle integrity, consistent with the role of muscle dysfunction in the parkin flight defect (Fig. 4 A and B). Muscle integrity was almost completely restored in parkin mutants ectopically expressing parkin in muscles (Fig. 4C). Analysis of proboscis muscle from parkin mutants revealed pathology similar to that of the IFM, indicating that this phenotype is not specific to the flight muscles (data not shown). However, the tergal depressor of trochanter muscle, involved in the jump response, and the larval body-wall muscles involved in larval locomotion are morphologically and functionally normal in parkin mutants (data not shown), indicating that only a subset of muscles are affected by loss of parkin function.

Figure 4.

Parkin mutants manifest muscle degeneration and mitochondrial pathology. (A–C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of longitudinal sections of IFMs show well preserved muscle in controls (A), contrasted with acute degeneration in parkin mutants (B) characterized by vacuole formation (arrow) and accumulation of cellular debris (arrowhead). Transgenic expression of parkin substantially restores muscle integrity (C), though occasional vacuoles are still seen (arrow). (Insets) Transverse section of IFMs. (D and G) Sections through parkin+ adult IFMs show a regular and compact myofibril arrangement (white arrows) with many electron-dense mitochondria (red arrowheads and Inset). (E and H) parkin− adult IFMs show an irregular and dispersed myofibrillar arrangement with diffuse Z-lines and M-bands. Mitochondria are grossly swollen and malformed showing disintegration of cristae (red arrowheads and Inset). (F and I) Myofibril and mitochondrial integrity can be restored by transgenic expression of parkin in muscle tissue. (J–O) The mitochondrial pathology is progressive and precedes myofibril degeneration. (J and M) IFMs from control 96-h pupae show many electron-dense mitochondria, whereas age-matched parkin mutants (K and N) already have mitochondria that are less electron-dense showing fewer cristae. (L and O) By 120 h, parkin− pupae still show intact myofibril structure, but the mitochondria are profusely swollen as the cristae continue to degenerate. Genotypes: parkin+: w; parkrvA/Df(3L)Pc-MK, parkin−: w; park25/Df(3L)Pc-MK, transgenic rescue: w; UAS-park; park25/24B-GAL4, park25. (Scale bars: D–L, 2 μm; M–O and Insets in D–F, 0.5 μm.) Z, Z-lines; M, M-bands; APF, after puparium formation.

Ultrastructural analysis of the IFM in 1- to 2-day-old parkin mutants revealed an overall decrease in the density of myofibrils, a broadening of the myofibril Z-line, and a shortening of the sarcomere length (Fig. 4 D and E). However, the myofibril structural alterations were variable with some indistinguishable from those of control flies. By contrast, swollen mitochondria manifesting severe disruption and disintegration of the cristae were a uniform feature of the IFM in parkin mutants (Fig. 4 D, E, G, and H). Transgenic expression of parkin in the musculature restores the myofibril integrity and mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 4 F and I). The temporal relationship between mitochondrial and myofibril pathology was investigated by analyzing IFM ultrastructure in parkin mutants at the pupal stage of development shortly after IFM formation. At 96 or 120 h after puparium formation the integrity of the myofibrils in parkin mutants was similar to controls, showing no signs of degeneration (Fig. 4 J–L). The only detectable difference in IFM ultrastructure between parkin mutants and control animals at the pupal stage of development was a disintegration of the mitochondrial matrix in parkin mutants (Fig. 4 M–O). These results demonstrate that mitochondrial pathology is an early indicator of muscle dysfunction and that the muscle pathology is degenerative in nature.

To determine whether muscle degeneration in parkin mutants proceeds through an apoptotic mechanism, the IFM in parkin mutants and age-matched control flies were subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP end labeling (TUNEL) staining (28). At 96 and 120 h after puparium formation, no TUNEL staining was detected in parkin mutants and control flies (Fig. 5 and data not shown). However, a dramatic increase in TUNEL-positive nuclei was observed in the IFM of 1-day-old adult parkin mutants relative to age-matched control flies, suggesting that the muscle mitochondrial defects ultimately result in cell death through an apoptotic mechanism (Fig. 5 C and D).

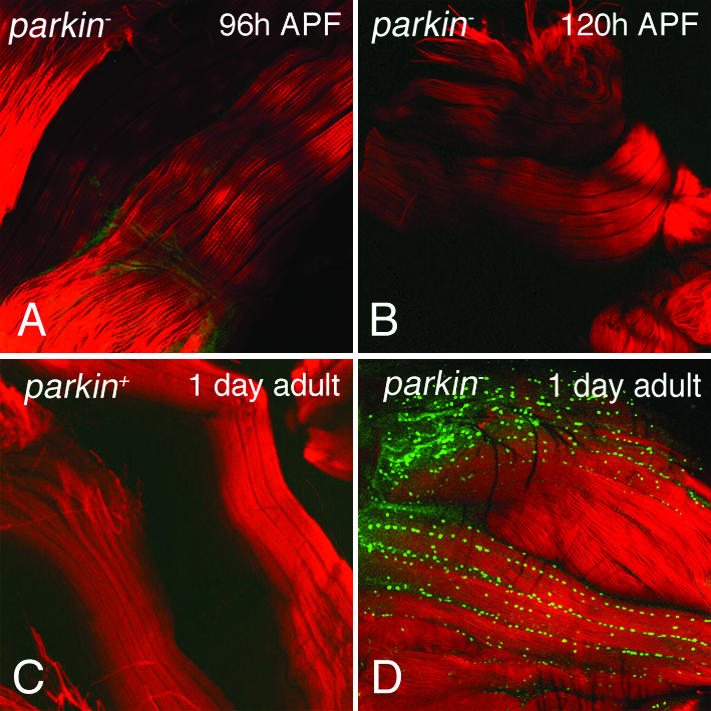

Figure 5.

parkin mutants exhibit apoptotic cell death of flight muscle. IFMs from 96-h (A) and 120-h (B) parkin mutant pupae exhibit a lack of TUNEL-positive nuclei. One-day-old control flies (C) also lack TUNEL-positive nuclei, whereas age-matched parkin mutants (D) have many apoptotic nuclei (green). Phalloidin (red) highlights muscle tissue. Genotypes: parkin+: w; parkrvA/Df(3L)Pc-MK, parkin−: w; park25/park25.

To examine the role of parkin in the brain, sections were prepared from flies at 1, 10, and 30 days of age. Standard histologic analysis revealed appropriate development of the major brain centers (Fig. 6 A and B). No obvious loss of neuropil integrity or cell cortical number was seen in aged parkin mutant flies compared with controls (Fig. 6 A and B). Because dopaminergic neurons are a preferential target in AR-JP, brain sections were also immunostained for tyrosine hydroxylase (27). Dopaminergic neurons of the dorsomedial, dorsolateral, and anteromedial clusters and the medulla were assessed. No clear neuronal loss was observed in any of these cell groups. Tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive terminal density was also generally preserved. However, cells of the dorsomedial dopaminergic cell cluster reliably showed shrinkage of the cell body and decreased tyrosine hydroxylase immunostaining in proximal dendrites in aged parkin mutants relative to controls (Fig. 6 C and D). No such changes were observed in other dopaminergic cell groups. The preferential effect on the dorsomedial cluster is intriguing given the enhanced toxicity of α-synuclein, another protein implicated in familial PD, in this cluster of dopaminergic neurons (27, 29).

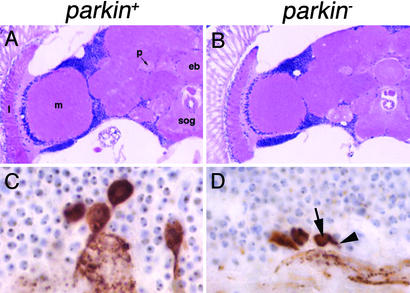

Figure 6.

Loss of parkin function does not cause general neuronal degeneration or dopaminergic neuron loss. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained frontal sections from control (A) compared with parkin mutant (B) flies at 30 days of age reveal appropriate organization of the nervous system including well-formed ellipsoid body (eb), peduncle (p), subesophageal ganglia (sog), medulla (m), and lamina (l). In addition, no age-related increase in neurodegeneration is evident in parkin mutants compared with controls in the cell cortex or neuropil. (C and D) Tyrosine hydroxylase immunostaining reveals similar number of neurons in the dorsomedial cluster in control flies (C) compared with parkin mutants (D), though shrinkage of the cell body (arrow) and decreased staining in the proximal dendrite (arrowhead) are frequently evident. Genotypes: parkin+: w; parkrvA/Df(3L)Pc-MK, parkin−: w; park13/Df(3L)Pc-MK.

Discussion

To investigate the biological role of Parkin and the mechanism by which loss of Parkin function results in selective cell death, we have created a Drosophila model of AR-JP through targeted disruption of a highly conserved Drosophila parkin ortholog. We show that Drosophila parkin null mutants are viable, but short-lived, and that loss of parkin function results in male sterility, locomotor defects, and structural alterations in dopaminergic neurons. The male sterile phenotype derives from a spermatid individualization defect in the male germ line, whereas the locomotor defects arise from apoptotic muscle degeneration.

An obvious difference between Drosophila parkin mutants and AR-JP concerns the tissues affected by loss of parkin function. Dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra appear to be the primary tissues affected in AR-JP individuals, whereas the most striking phenotypes in Drosophila parkin mutants derive from muscle and germ-line pathology. Nevertheless, the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for pathology in these different tissues may be highly conserved. Indeed, ultrastructural examination of the male germ line and IFM in parkin mutants reveals mitochondrial defects as a common characteristic of pathology in these distinct tissue types. Although further work will be required to establish the relevance of mitochondrial pathology to the spermatid individualization defect, studies of IFM pathogenesis strongly indicate that mitochondrial pathology is a primary defect. Thus, these results suggest that the Drosophila parkin phenotypes derive from a common origin of mitochondrial dysfunction. There are a variety of cellular insults capable of producing the specific mitochondrial structural alterations observed in parkin mutants, and further work will be required to elucidate the mechanism by which loss of parkin function triggers mitochondrial pathology and ultimately cell death.

Our finding that mitochondrial pathology and apoptosis are prominent features of IFM degeneration raises the possibility that similar mechanisms underlie dopaminergic neuron loss in AR-JP. Although previous studies have not addressed a role for parkin in mitochondrial integrity or apoptosis, a substantial body of evidence suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis are important factors underlying neurodegeneration in idiopathic PD (30–32). Thus, our findings provide a potential mechanistic link between AR-JP and the broader spectrum of idiopathic PD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project Database and Bloomington Stock Center for sequence data and fly stocks used in this work; S. Grote, J. Golby, F. Remington, B. Schneider, and B. Zhang for help with technical aspects of this work; and R. Monnat, A. LaSpada, F. Perez, P. Wes, and members of the Pallanck lab for critical comments on the manuscript. Finally, we give special thanks to B. Wakimoto for insight into the parkin male sterile phenotype and for providing unpublished information about a large collection of male sterile mutants, and to E. Koundakjian and C. Zuker for providing the mutant strains. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 1RO1NS41780-01 (to L.J.P.) and 1RO1NS41536-01 (to M.B.F.).

Abbreviations

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- AR-JP

autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism

- IFM

indirect flight muscle

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP end labeling

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Vaughan J R, Davis M B, Wood N W. Ann Hum Genet. 2001;65:111–126. doi: 10.1017/S0003480001008557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorell J, Johnson C, Rybicki B, Peterson E, Richardson R. Neurology. 1998;50:1346–1350. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwinn-Hardy K A. Movement Disorders. 2002;14:645–656. doi: 10.1002/mds.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizuno Y, Saitoh T, Sone N. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;143:294–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicklas W, Vyas I, Heikkila R. Life Sci. 1985;36:2503–2508. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsay R, Salach J, Dadgar J, Singer T. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:269–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks A, Chadwick C, Gelbard H, Cory-Slechta D, Federoff H. Brain Res. 1999;823:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betarbet R, Sherer T B, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuna M, Panov A V, Greenamyre J T. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janetzky B, Hauck S, Youdim M, Riederer P, Jellinger K, Pantucek F, Zochling R, Boissl K, Reichmann H. Neurosci Lett. 1994;169:126–128. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schapira A, Cooper J, Dexter D, Clark J, Jenner P, Marsden C. Lancet. 1989;1:1269. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schapira A, Cooper J, Dexter D, Clark J, Jenner P, Marsden C. J Neurochem. 1990;54:823–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizuno Y, Ohta S, Tanaka M, Takamiya S, Suzuki K, Sato T, Oya H, Ozawa T, Kagawa Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattori N, Tanaka M, Ozawa T, Mizuno Y. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:563–571. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imai Y, Soda M, Takahashi R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35661–35664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S-I, Mizuno Y, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Iwai K, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Suzuki T. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Gao J, Chung K K K, Huang H, Dawson V L, Dawson T M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimura H, Schlossmacher M G, Hattori N, Frosch M P, Trockenbacher A, Schneider R, Mizuno Y, Kosik K S, Selkoe D J. Science. 2001;293:263–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1060627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai Y, Soda M, Inoue H, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Takahashi R. Cell. 2001;105:891–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung K K K, Zhang Y, Lim K L, Tanaka Y, Huang H, Gao J, Ross C A, Dawson V L, Dawson T M. Nat Med. 2001;7:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranganayakulu G, Schulz R A, Olson E N. Dev Biol. 1996;176:143–148. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engels W R, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Eggleston W B, Sved J. Cell. 1990;62:515–525. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsunoda S, Sierralta J, Sun Y, Bodner R, Suzuki E, Becker A, Socolich M, Zuker C S. Nature. 1997;388:243–249. doi: 10.1038/40805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brand A, Perrimon N. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benzer S. Sci Am. 1973;229:24–37. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1273-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benzer S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:1112–1119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.3.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feany M B, Bender W W. Nature. 2000;404:394–398. doi: 10.1038/35006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bortner C D, Oldenburg B E N, Cidlowski J A. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88932-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auluck P, Chan H, Trojanowski J, Lee V, Bonini N M. Science. 2002;295:809–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orth M, Schapira A. Neurochem Int. 2002;40:533–541. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betarbet R, Sherer T B, Di Monte D, Greenamyre J T. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:499–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen J K. BioEssays. 2001;23:640–646. doi: 10.1002/bies.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]