Abstract

The mechanisms coordinating adhesion, actin organization, and membrane traffic during growth cone migration are poorly understood. Neuritogenesis and branching from retinal neurons are regulated by the Rac1B/Rac3 GTPase. We have identified a functional connection between ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) 6 and p95-APP1 during the regulation of Rac1B-mediated neuritogenesis. P95-APP1 is an ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein (ArfGAP) of the GIT family expressed in the developing nervous system. We show that Arf6 has a predominant role in neurite extension compared with Arf1 and Arf5. Cotransfection experiments indicate a specific and cooperative potentiation of neurite extension by Arf6 and the carboxy-terminal portion of p95-APP1. Localization studies in neurons expressing different p95-derived constructs show a codistribution of p95-APP1 with Arf6, but not Arf1. Moreover, p95-APP1–derived proteins with a mutated or deleted ArfGAP domain prevent Rac1B-induced neuritogenesis, leading to PIX-mediated accumulation at large Rab11-positive endocytic vesicles. Our data support a role of p95-APP1 as a specific regulator of Arf6 in the control of membrane trafficking during neuritogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Actin dynamics during growth cone navigation evolve into stabilization of the cytoskeleton and neurite elongation (Tanaka and Sabry, 1995). Although a large amount of information exists about the extracellular mechanisms driving these processes, large gaps still exist in the comprehension of the corresponding intracellular events. Neurite extension requires the concerted development of a number of events, including actin polymerization, formation of new adhesive sites, and membrane addition, to extend the surface of the elongating neurite. The Rho family of small GTPases is implicated in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and adhesion during neuronal differentiation (reviewed by Luo, 2000). Analyses in different organisms and studies with primary neurons have shown that Rac acts as a regulator of process outgrowth and axonal guidance (reviewed by Luo, 2000). Among Rho GTPases, Rac stimulates actin polymerization at the cell surface (Ridley and Hall, 1992) necessary for the crawling of the growth cone.

In our laboratory, we have identified Rac1B, a Rac expressed during neural development (Malosio et al., 1997), which is the orthologue of mammalian Rac3 (Haataja et al., 1997). The overexpression of Rac1B/Rac3 in retinal neurons specifically stimulates neurite extension and branching on laminin (Albertinazzi et al., 1998). Expression of mutant Rac1B abolishes neurite formation induced by the endogenous GTPase.

Recently, we have identified p95-APP1 (Di Cesare et al., 2000), an ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein (ArfGAP) of the GIT family (reviewed by Donaldson and Jackson, 2000; de Curtis, 2001). The data available in the literature and searches of the available genomic and enhanced sequence tag banks have recently led us to conclude that avian p95-APP1 is most likely the orthologue of mammalian GIT1. P95-APP1 is able to interact with the putative exchanging factor PIX (Manser et al., 1998), and with the focal adhesion protein paxillin (Turner et al., 1999). By forming a stable complex with these proteins and with the Rac effector PAK, which binds the Src homology 3 domain of PIX (Manser et al., 1998), p95-APP1 can interact with Rac1B in a GTP-dependent manner (Di Cesare et al., 2000). We will refer to this complex as the p95-complex. The molecular dissection of the function of this multidomain protein in nonneuronal cells has shown that, although the carboxy-terminal portion has a diffuse distribution and induces protrusive activity in fibroblasts (Di Cesare et al., 2000), ArfGAP-deficient mutants specifically accumulate at large, Rab11-positive vesicles, suggesting a role for this ArfGAP in membrane recycling (Matafora et al., 2001).

The small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) 6 is a substrate for various members of this family of ArfGAPs in vitro (Vitale et al., 2000). Arf6 colocalizes with p95-APP1–derived constructs at the endocytic compartment of transfected fibroblasts (Di Cesare et al., 2000) and is implicated in the regulation of membrane recycling between the endosomal compartment and the cell surface (Peters et al., 1995; Radhakrishna et al., 1996). Colocalization of Rac1 and Arf6 both at the plasma membrane and recycling endosomes, and block of Rac1-stimulated ruffling by the GTP binding-defective N27Arf6 mutant (Radhakrishna et al., 1999), have suggested that the ability of Arf6 to influence Rac1-mediated lamellipodia depends in part on the regulation of its trafficking to the plasma membrane.

Recently, a model has been proposed in which p95-APP1 may regulate membrane recycling to sites of Rac activation during cell motility (de Curtis, 2001). Herein, we have analyzed the role played by Arf6 and the p95 complex in Rac1B-induced neurite extension in primary neurons. We show a specific functional connection between Arf6 and p95-APP1 during Rac1B-mediated neurite extension and branching. ArfGAP mutants of p95-APP1 were found to dramatically inhibit neurite extension and to accumulate specifically at large Rab11-positive endosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Fertilized chicken eggs were purchased from Allevamento Giovenzano (Vellezzo Bellini, Italy). Laminin-1 was purified from Engelbreth-Holm Swarm sarcoma as published previously (Timpl et al., 1979). The polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) against PIX (Manser et al., 1998), Arf6 (Gaschet and Hsu, 1999), Rab11 (Sonnichsen et al., 2000), early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1; Simonsen et al., 1998), have been described previously. Other antibodies included anti-neurofilament 3A10 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Serafini et al., 1996), obtained by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA); anti-FLAG M5 (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); pAb anti-FLAG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); anti-hemagglutinin (HA)-Tag mAb 12CA5 and anti-HA-Tag pAb (Babco, Richmod, CA); anti-Myc mAb 9E10 (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy); anti-paxillin mAb (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); mAb against LEP100 (Fambrough et al., 1988); and anti-βCOP mAb (Sigma-Aldrich). Secondary antibodies for immunofluorescence were from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN) and Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Other reagents included Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI), Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase (Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ), restriction enzymes (Roche Diagnostics), [α-35S]dATP, [α-32P]dCTP, 125I-anti-mouse Ig, and 125I-protein A (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Constructs

The pBK-Arf6, pBK-N27Arf6, and pBK-L67Arf6 plasmids were obtained by subcloning the cDNAs corresponding to avian Arf6, Arf6(N27), and Arf6(L67) into the pBK-CMV vector (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany). The cDNA for chicken Arf1 and Arf5 were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from an E15 chick brain cDNA library. The cDNAs for Arf1, Arf5, Arf6, N27Arf6, and L67Arf6 were cloned into a pBK-CMV vector modified to include a sequence coding for a HA tag at the carboxy terminus of the Arf proteins. The pBK-Arf1-HA and pBK-Arf5-HA plasmids were used to produce pBK-N31Arf1-HA, pBK-L71Arf1-HA, pBK-N31Arf5-HA, and pBK-L71Arf5-HA, with degenerate oligonucleotides in combination with the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The pcDNA-I-HA-Rac1B, pFLAG-p95, pFLAG-p95-C, pFLAG-p95-C2, pFLAG-p95-K39, pFLAG-p95-N, and pFLAG-LacZ plasmids were described previously (Malosio et al., 1997; Di Cesare et al., 2000; Matafora et al., 2001). The pFLAG-p95-ΔSHD plasmid, lacking most of the region coding for the Spa2 homology domain (SHD), was prepared by inserting a PCR fragment corresponding to the amino-terminal portion of p95-APP1, obtained by PCR with the oligonucleotides 5′-CCCAAGCTTATGTCCCGGAAGGCGCAGC-3′ and 5′-CCGATATCCAGGTCCAGGC TGTCTGCC-3′, into the pFLAG-p95-C2 vector, from which the sequence coding for most of the SHD domain was first removed by digesting with HindIII and EcoRV. The pCMV6 m/PAK1 plasmid coding for the Myc-tagged PAK1, and the pXJ40-HA-βPIX plasmid coding for the HA-tagged βPIX polypeptide were described previously (Manser et al., 1998; Bernard et al., 1999).

Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was prepared from different organs from E10 chicken embryos, and from E10 CEFs, by a single-step RNA isolation method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). Northern blot analysis of total RNA (20 μg/lane) was performed as described previously (Lehrach et al., 1977). Blots were hybridized with a 1-kb probe corresponding to the 5′ region of the cDNA for p95-APP1. Hybridization took place in hybridization buffer supplemented with 32P-labeled probes (1–2 × 106 cpm ml−1) for 21 h at 65°C. After high-stringency washes at 65°C, x-ray films were exposed for 3–7 d to the hybridized filters.

Culture and Transfection of Cells

Neural retinal cells were prepared from E6 chick neural retinas and cultured on 0.2 mg ml−1 poly-d-lysine and 40 μg ml−1 laminin-1 (Albertinazzi et al., 1998). For transfection by electroporation, retinal cells were resuspended in cytomix, pH 7.6 (120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 10 mM K2HPO4/KH2PO4, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, and 5 mM MgCl2) to a final concentration of 65 millions of cells ml−1. Then 200 μl of cell suspension was placed in a Gene Pulser cuvette (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and 50 μg of plasmid was added (40 μg of each plasmid in cotransfection experiments). After an incubation on ice for 5 min, cuvettes were subjected to two sequential pulses at 0.4 kV and 125 μF, resuspended in 10 ml of serum-free retinal growth medium, and plated on polylysine + laminin-coated coverslips. Cells were cultured for 20–24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 and fixed for immunofluorescence. Quantification of the effects of the overexpression of the constructs in retinal neurons were made by examining transfected, neurofilament-positive neurons, or cotransfected neurons. For each type of transfection, at least 50 neurons were morphologically examined from at least two distinct experiments (total of 100 neurons/experimental condition). Long neurites were equal or longer than three cell body diameters, short neurites were shorter than three cell body diameters. For measures of total neurite length and of number of neurite terminals, a total of 30 neurons from two independent experiments were examined by using the Image-Pro Plus program (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Affinity Chromatography

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Rac1B was produced and purified as described previously (Albertinazzi et al., 1998). Then 0.5 mg of GST-Rac1B bound to 50-μl aliquots of glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) was loaded for 10 min at 37°C with 0.1 mM guanosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) or guanosine 5′-O-(2-thio)diphosphate (GDPβS) in 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Loading was stopped by adding MgCl2 to 5 mM final concentration. Protein (3–3.5 mg) from E6 retinas extracts in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 5 mM MgCl2, and 20 μg ml−1 each of antipain, chymostatin, leupeptin, and pepstatin) were added to beads and incubated for 1 h at 4°C with rotation. Beads were washed three times with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer, loaded onto 7.5% polyacrylamide gel for SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence

Transfected cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde and processed for indirect immunofluorescence. Fluorescent images were collected using the Image-Pro Plus software package (and processed using Adobe Photoshop 5.0).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Transfected COS-7 cells were extracted with lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM DTT, and 20 μg ml−1 each of antipain, chymostatin, leupeptin, and pepstatin). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation and incubated for 2 h with rotation at 4°C with 40 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads preincubated with10 μl of preimmune serum. The unbound material was incubated for 2 h with rotation at 4°C with 40 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads preincubated with 10 μl of immune anti-PIX serum. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with 0.5 ml of lysis buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. For the detection of primary antibodies, blots were incubated with 0.2 μCi ml−1 of either 125I-anti-mouse Ig, or 125I-protein A (Amersham Biosciences), washed, and exposed to Hyperfilm-MP (Amersham Biosciences).

RESULTS

Expression of p95-APP1 in Neural Tissue

Expression of the p95-APP1 gene in embryonic tissues was investigated by Northern blot analysis (Figure 1 A). A 2.8-kb transcript was detected by hybridizing filters with total RNA isolated from various tissues of embryonic day 10 (E10) avian embryos and from E10 chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs). P95-APP1 was particularly abundant in neural tissues, including neural retina. In embryonic day 6 (E6) neural retinas, the source of neurons used in this study, the level of the transcript was relatively low. Because p95-APP1 has been shown to interact with PIX and paxillin (Di Cesare et al., 2000), we have checked for the presence of this complex in E6 neural retinas. P95-APP1, PIX, and paxillin were specifically detected after chromatography with retinal extracts on GST-Rac1B-GTPγS, but not on GST-Rac1B-GDPβS (Figure 1B). These data show the existence of an endogenous p95-APP1/PIX/paxillin complex in E6 neural retinal cells.

Figure 1.

Expression of p95-APP1 in neural cells. (A) Northern blot analysis (top) on total RNA (bottom) prepared from different chick E10 tissues, from E6 retina, and from CEFs. The filter was incubated with a cDNA probe specific for p95-APP1. Then 20 μg of total RNA was loaded in each lane. (B) Characterization of the endogenous p95-APP1 complex in E6 neural retina. A lysate from E6 neural retinas was incubated with agarose beads bound to GST-Rac1B loaded with GDP-β-S (left lane) or GTPγS (right lane). Eluates were immunoblotted with anti-p95-APP1 (top), anti-PIX (middle), and anti-paxillin antibodies (bottom). (C) P95-APP1–derived constructs used in this study. ANK, three ankyrin repeats; LZ, coiled coil region with leucine zipper; PBS, paxillin binding subdomain.

Mutants of p95 Lacking a Functional ArfGAP Domain Inhibit Neuritogenesis

To look at the effects of p95-APP1 on neurite extension, we have transfected E6 retinal neurons with a number of p95-derived proteins (Figure 1C) and cultured the transfected cells for 1 d on laminin-1 to induce neurite extension (Adler et al., 1985). Most untransfected neurons, or neurons expressing a control protein (β-galactosidase) extend one long, poorly branched neurite (Figure 2, A and B). Overexpression of wild-type p95-APP1 (Figure 2, C and D) as well as coexpression of p95-APP1 with βPIX (our unpublished data) did not affect the morphology of retinal neurons. We have previously shown that the expression of the carboxyterminal p95-C polypeptide, including the paxillin-binding domain (Figure 1C), enhances the formation of protrusions in fibroblasts (Di Cesare et al., 2000). The expression of p95-C did not have such a dramatic effect in neurons, although it was more common to find neurons with two neurites (Figure 2E), and resulted in an increase of total neurite length/neuron compared with neurons expressing β-galactosidase (Figure 3D). In contrast, neuritogenesis was heavily affected by the expression of p95-C2 (Figure 2F), which differed from p95-C for the presence of the SHD somain required for binding to PIX (Figure 1C). Approximately 60% of the p95-C2–transfected neurons showed complete inhibition of neurite formation (Figure 2L). Similar findings were observed by expressing the p95-K39 protein (Matafora et al., 2001), in which the mutation of a conserved arginine, corresponding to arginine 39 in p95-APP1, is known to drastically reduce the GAP activity in a number of ArfGAPs (Mandiyan et al., 1999; Jackson et al., 2000; Randazzo et al., 2000; Szafer et al., 2000). P95-K39 clearly inhibited neurite extension (Figure 2G). P95-K39 led to lack of neurites in ∼50% of the transfected neurons (Figure 2L), with several neurons showing vacuoles similar to those observed upon p95-C2 expression (Figure 2G). These data indicate the requirement of an intact ArfGAP domain in p95-APP1 for neurite outgrowth on laminin. Both p95-C2 and p95-K39 are able to interact with PIX and paxillin in nonneuronal cells (Matafora et al., 2001). In retinal neurons, endogenous paxillin redistributed from the diffuse punctate pattern observed in nontransfected neurons, to the large p95-C2–positive vesicles (Figure 2, H and I). Concentration at large p95-C2 vesicle was also observed in cells cotransfected with PIX (Figure 2J) or PAK (Figure 2K). Similar results were observed in neurons expressing p95-K39 (our unpublished data). Therefore, mutations affecting the ArfGAP domain of p95-APP1 induced the accumulation of the entire p95-complex at the large vesicles. These data indicate a correlation between the formation of the large vesicles, and the inhibition of neuritogenesis by p95-C2.

Figure 2.

Effect of p95-APP1 ArfGAP mutants on neuritogenesis and localization at large vesicles. (A–K) Localization of p95-derived constructs expressed in E6 retinal neurons. Expression of full-length p95 (C) and p95-C (E) showed a diffuse distribution of the proteins along the neurites. Expression of either the truncated p95-C2 (F and H–K) or the p95-K39 mutant (G) inhibited neuritogenesis and induced the accumulation of the transfected proteins at large cytopalsmic vesicles. Endogenous paxillin (I), overexpressed PIX (J), and overexpressed PAK (K) colocalized with p95-C2 at the large endocytic vesicles. Bar, 10 μm (A–E); 5 μm (F and G); and 7 μm (H–K). (L) Effects of the expression of different p95-APP1 mutants on neuritogenesis. Data are expressed as percentage of neurofilament-positive neurons with no, short, or long neurites, as detailed in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Control neurons were transfected with β-galactosidase. Values are means ± SD from two experiments.

Figure 3.

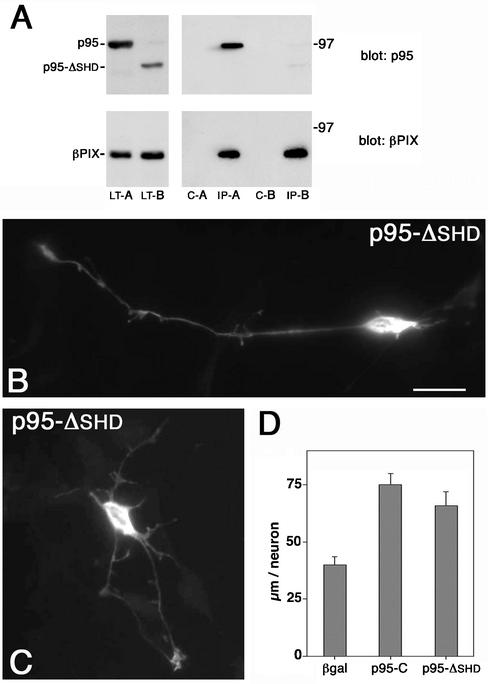

Expression of the p95-ΔSHD mutant in retinal neurons. (A) COS-7 cells were cotransfected to express wild-type βPIX together with either full-length FLAG-p95-APP1 (A) or with FLAG-p95-ΔSHD (B). Lysates (LT-A and LT-B) were first immunoprecipitated with preimmune serum (c-A and c-B); the unbound material was then immunoprecipitated with anti-PIX immune serum (IP-A and IP-B). Samples were prepared in duplicate. One set was used for immunoblotting with anti-FLAG mAb (top filters); the second set was used for immunoblotting with the anti-PIX pAb (bottom filters). (B and C) Retinal neurons were transfected with pFLAG-p95-ΔSHD and treated for immunofluorescence with the anti-FLAG mAb. (D) Quantitation of the total neurite length/neuron in retinal neurons transfected with β-galactosidase, p95-C, or pFLAG-p95-ΔSHD. Quantitation was done on 30 neurons for each type of transfectant. Bars, SEM.

The differences between p95-C2 and p95-C strongly suggest that the SHD domain responsible for PIX binding is critical for the accumulation of p95-C2 at the large vesicles, which results in the inhibition of neuritogenesis. This conclusion was supported by the analysis of the effects of the expression of p95-ΔSHD, in which the SHD domain responsible for the interaction with PIX had been deleted (Figure 1C). Biochemical analysis in nonneuronal cells showed that in contrast to the wild-type p95-APP1, the p95-ΔSHD polypeptide could not be efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with wild-type βPIX (Figure 3A). Transfection of this mutant induced long neurites (Figure 3B) and branching in a fraction of the transfected neurons (Figure 3C). Quantitation showed that the increase in total neurite length/neuron by p95-ΔSHD was similar to that observed by expressing p95-C (Figure 3D).

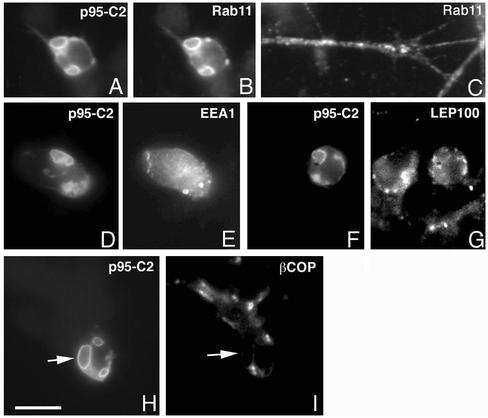

Specific Accumulation of p95-C2 at Recycling Endosomes

The large vesicles positive for p95-C2 were positive for Rab11 (Figure 4, A and B), a functional marker of the endocytic recycling compartment (Ullrich et al., 1996). The accumulation of p95-C2 at this compartment was specific, because the subcellular distribution of both the early endocytic marker EEA1 (Figure 4, D and E), the lysosomal marker LEP100 (Figure 4, F and G), and the Golgi marker βCOP (Figure 4, H and I) did not show any evident overlap with the p95-C2–positive vesicles. For comparison, in nontransfected neurons Rab11 was distributed in a cytoplasmic punctated pattern along neurites and at the growth cone (Figure 4C). These data show that ArfGAP-defective p95 proteins induced a dramatic and specific alteration of the morphology of the neuronal recycling compartment.

Figure 4.

Specific localization of p95-C2 at large Rab11-positive vesicles. Neurons expressing p95-C2 were costained with antibodies against markers for distinct intracellular compartments. P95-C2 colocalized with the recycling endosomal marker Rab11 (A and B), whereas no colocalization was evident with the early endosomal marker EEA1 (D and E), the lysosomal marker LEP100 (F and G), and the Golgi marker βCOP (H–I). In C is shown the normal appearance of the Rab11 compartment in untransfected retinal neurons. Bar, 5 μm.

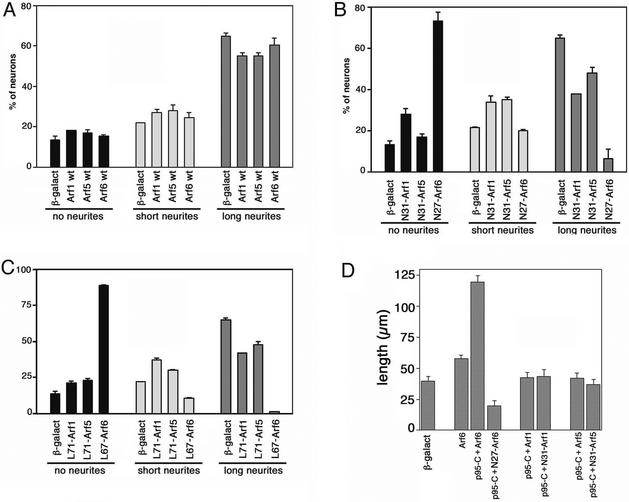

Arf6 Activity Is Necessary for Neurite Extension

Mammalian GIT proteins have GAP activity for different Arf proteins in vitro, including Arf6 (Vitale et al., 2000). The Arf affected by p95-APP1 activity in vivo has not been identified yet. We have started by analyzing the effects of the expression of members of class I (Arf1), class II (Arf5), and class III (Arf6) Arfs on neurite extension. Overexpression of any of the three wild-type proteins did not evidently affect the percentage of neurons with a long neurite (Figure 5A). In contrast, the GTP binding-defective N27Arf6 mutant strongly inhibited the formation of neurites, with >70% of the transfected cells without neurite (Figure 5B). A strong inhibition of neurite formation was observed also when the constitutively active mutant L67Arf6 was expressed, with >85% of transfected neurons without neurites (Figure 5C). In comparison, weaker effects on neurite extension were observed in cells expressing the corresponding mutants for Arf1 and Arf5. The observed effects on neuritogenesis were not due to differences in the levels of expression of mutants from distinct Arf classes, as checked by quantitation of the overexpressed proteins at the single cell level (our unpublished data). These results show that Arf6 plays a major role among the tested Arfs during neurite extension.

Figure 5.

Wild-type Arf6 is required for neuritogenesis from retinal neurons. E6 retinal neurons were transfected with wild-type (A), GTP-binding–defective (B), or GTP-hydrolysis–defective (C) Arf1, Arf5, or Arf6 GTPases. Data are expressed as percentage of transfected, neurofilament-positive neurons with no, short, or long neurites, as detailed in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Control neurons were transfected with β-galactosidase. Values are means ± SD from two experiments. (D) Effects on neuritogenesis of the coexpression of p95-C with wild-type or mutant Arf proteins. Quantitation was performed by evaluating the total neurite length/cell in 30 neurons for each experimental condition. Bars, SEM.

We have then further explored the possible functional relationship between Arf6 and p95-APP1 during neuritogenesis. We noticed that coexpression of wild-type Arf6 with the truncated p95-C protein resulted in several neurons with evidently longer, often branched neurites (our unpublished data). In comparison, coexpression of either Arf1 or Arf5 with p95-C did not seem to evidently affect neurite length (our unpublished data). To quantify these effects we measured the total neurite length/neuron in cotransfected neurons (Figure 5D). The quantitation clearly shows that the potentiation of neuritogenesis observed by the coexpression of p95-C with wild-type Arf6 was not observed by coexpressing p95-C with either wild-type Arf1 or Arf5. Moreover, coexpression of the GTP-binding defective N27Arf6 with p95-C not only prevented the potentiation but also inhibited basal neurite extension compared with control neurons (Figure 5D). Together, our functional analysis shows a predominant role of Arf6 on neurite extension in retinal neurons with respect to other Arfs and indicates a specific functional connection between Arf6 and p95-APP1.

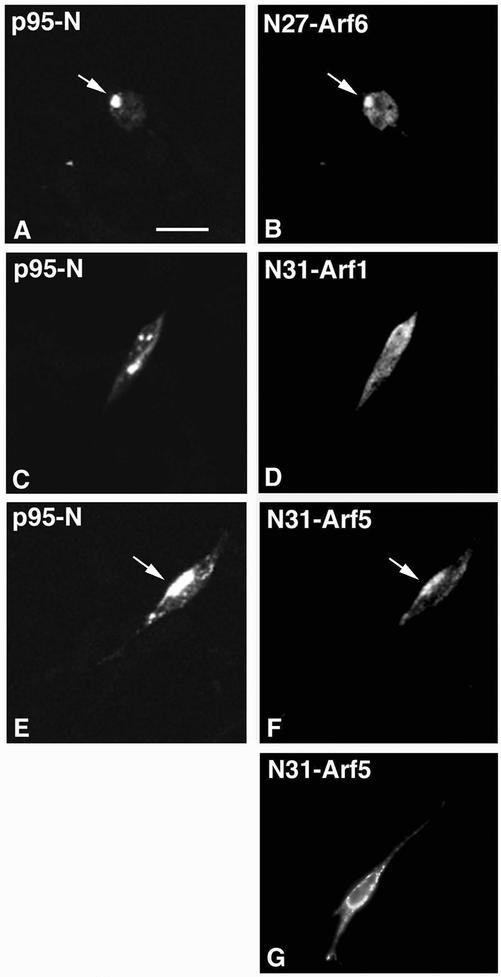

Specific Colocalization of Arf6 with p95-APP1–derived Proteins in Retinal Neurons

We have recently shown that the truncated p95-N protein, including the ArfGAP domain (Figure 1C), colocalized at endocytic vesicles with the inactive N27Arf6 protein (Matafora et al., 2001). We confirmed this finding in retinal neurons, where N27Arf6 colocalized intracellularly with p95-N (Figure 6, A and B). Arf6 is the only known member of class III Arfs. We then looked at the distribution of members of class I and II Arfs for comparison. The GTP-binding–defective N31Arf1 protein did not colocalize with p95-N (Figure 6, C and D), whereas the corresponding N31Arf5 mutant colocalized with p95-N (Figure 6, E and F). This mutant was found at vesicles also when expressed in the absence of p95-N (Figure 6G). The lack of colocalization of N31Arf1 with p95-N was not due to a lower level of expression of N31-Arf1, as determined by quantitation of the intensity of fluorescence in cells transfected with the three mutants (our unpublished data). Our data suggest that p95-APP1 may establish a functional interaction with Arf6 and Arf5 in vivo.

Figure 6.

Arf6 and Arf5 colocalize with p95-N. Neurons were cotransfected with the amino-terminal p95-N construct together with N27Arf6 (A and B), N31Arf1 (C and D), or N31Arf5 (E and F). Analysis by confocal fluorescence microscopy of cells fixed one day after transfection shows colocalization of 95-N with N27Arf6 and N31Arf5 (arrows), but not with N31Arf1. (G) Distribution of N31Arf5 in neurons transfected with N31Arf5 only. Bar, 5 μm.

When overexpressed, the wild-type Arf6 showed a diffuse distribution along neurites, without visibly affecting the morphology of neurons (Figure 7A). In contrast, overexpressed wild-type Arf1 showed a perinuclear staining, which largely overlapped with the distribution of the Golgi marker βCOP (Figure 7, B and C). It has recently been shown that the overexpression of GIT2 caused the redistribution of βCOP, whose subcellular distribution is regulated by Arf1, but not Arf6 (Mazaki et al., 2001). Overexpression of p95-APP1 did not affect the distribution of βCOP in retinal neurons (our unpublished data). Moreover, in contrast to wild-type Arf1 (Figure 7, F and G), wild-type Arf6 showed a clear colocalization with truncated p95-C2 at large vesicles (Figure 7, D and E). When p95-C2 was coexpressed with wild-type Arf5 (Figure 7, H and I), the colocalization between the two polypeptides was not evident in most cells, even when analyzed by confocal microscopy (our unpublished data). Together, these data indicate that in vivo p95-APP1 is a regulator of Arf6 and possibly Arf5, whereas they exclude a role for Arf1. In this direction, it is interesting to observe that the expression of the GTP hydrolysis-defective L67Arf6 mutant, which strongly inhibited neurite outgrowth (Figure 5C), resulted in the localization of this polypeptide at intracellular vesicles (Figure 7, J and K).

Figure 7.

Arf6 colocalizes with p95-C2. (A–C) Neurons were transfected with wild-type Arf6, or Arf1, and analyzed by immunofluorescence 1 d after transfection. In contrast to the diffuse distribution of Arf6 (A), Arf1 (B) colocalized with the endogenous Golgi marker βCOP (C). In retinal cells cotransfected with wild-type Arf proteins and p95-C2, a clear colocalization at large vesicles of wild-type Arf6 with p95-C2 could be observed (D and E). In contrast, neither wild-type Arf1 (F and G) nor wild-type Arf5 (H and I) colocalized with p95-C2–positive large vesicles. (J and K) distribution of overexpressed L67Arf6 in retinal neurons. Bars, 5 μm.

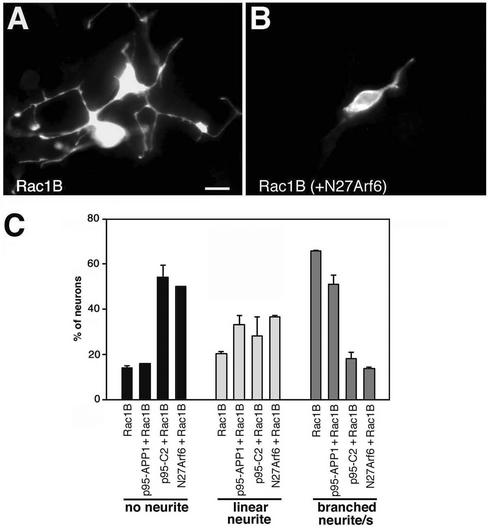

Wild-Type Arf6 and p95-APP1 Are Required for Rac1B-potentiated Neuritogenesis

E6 retinal neurons express both Rac1 and Rac1B/Rac3 GTPases (Malosio et al. 1997). We have previously shown that retinal neurons require low levels of endogenous Rac1B for basal neurite extension (Albertinazzi et al., 1998), whereas overexpression of Rac1B induces the generation of several branched neurites (Figure 8A). Coexpression of Rac1B with full-length p95-APP1 resulted in a small reduction in the percentage of cotransfected neurons with branched neurites compared with Rac1B-transfected cells (Figure 8C). No significant effects were observed between the two conditions on the average number of branches/neuron (our unpublished data). Coexpression of N27Arf6 strongly reduced Rac1B-induced branching and neuritogenesis in most cotransfected neurons (Figure 8B), with a fivefold decrease in the percentage of neurons with branched neurites, and a 3.6-fold increase of neurons without neurites, compared with neurons expressing Rac1B only (Figure 8C). Rac1B-potentiated neurite outgrowth was inhibited also by the coexpression of the truncated p95-C2 polypeptide (Figure 8C). Interestingly, in cotransfected cells wild-type Rac1B localized at the large p95-C2–positive vesicles (our unpublished data). Together, these results show that both N27Arf6- and ArfGAP-defective p95-C2 have dominant negative effects on Rac1B-mediated neurite extension on laminin.

Figure 8.

N27Arf6- and ArfGAP-deficient p95-C2 inhibit Rac1B-enhanced neurite branching. Enhanced neuritogenesis in E6 retinal neurons overexpressing wild-type Rac1B alone (A) was inhibited by coexpression of the GTP-binding–defective N27Arf6 mutant (B). Bar, 5 μm. (C) Quantitation ± SD of the effects of the expression of the indicated constructs on neurite branching; for each experimental condition, branching was evaluated in a total of 100 neurons from two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies have led to the identification of Rac1B, a Rho family GTPase specifically expressed during neuronal development (Malosio et al., 1997). Rac1B has a potentiating effect on neuritic development and branching (Albertinazzi et al., 1998). More recently, we have identified a protein complex specifically interacting with active GTP-bound Rac GTPases (Di Cesare et al., 2000), which includes p95-APP1, a member of an ArfGAP family, including the mammalian GIT1 and GIT2 proteins (Donaldson and Jackson, 2000), which correspond to avian p95-APP1 and PKL/p95-APP2, respectively (Turner et al., 1999; Paris et al., 2002). The characterization of the p95 complex in nonneuronal cells has led us to propose a role for this protein in connecting membrane traffic with actin dynamics during cell motility (de Curtis, 2001). In this study, we have analyzed the role of this complex in neurite development from primary neurons. The major findings from this work are the following: first, mutation/deletion of the ArfGAP domain of p95-APP1 leads to the accumulation of the p95 complex at large Rab11-positive vesicles, and to the concomitant inhibition of neurite extension; second, morphological and functional analysis with different Arf proteins has revealed a specific functional connection between Arf6 and the ArfGAP p95-APP1 during neurite extension; and third, Arf6 activity is specifically required for Rac1B-mediated neurite elongation.

The complex structure of p95-APP1 has made essential the use of deletion mutants to explore its function. In neurons, overexpression of the full-length protein or of the carboxy-terminal p95-C protein does not induce dramatic effects on neuronal morphology. In contrast, the expression of proteins with a mutated or deleted ArfGAP domain, but preserving the PIX-binding site, drastically inhibits neurite extension. Such inhibition is accompanied by the specific accumulation of the p95-complex at enlarged vesicles positive for Rab11, a functional marker of the endocytic recycling compartment (Ullrich et al. 1996; Ren et al. 1998). This indicates a functional connection between membrane recycling and neurite extension in retinal neurons.

Growth cones are sites of intense endocytosis, and require an equivalent membrane flow back to the surface to maintain equilibrium. Recent work has shown the existence of dynamic recycling endosomes in axons and dendrites of developing hippocampal neurons (Prekeris et al., 1999). The endocytic/exocytic mechanism may represent a dynamic reservoir of mobile membrane to quickly respond to extracellular stimuli, leading to growth cone-mediated neurite extension or retraction (Craig et al., 1995). A contribution to neurite progression may therefore come also from endocytosed, recycled membranes; membrane recycling at the growth cone has recently been demonstrated (Diefenbach et al., 1999). In this direction, one interpretation of our results is that the p95-APP1 ArfGAP mutants (p95-C2 and p95-K39) interfere with vesicle recycling along the neurite, leading to membrane accumulation in the soma, with ensuing inhibition of neurite extension.

Further support to the role of membrane recycling during neurite extension comes from the specific effects of Arf6 on neurites. Arf6 is implicated in membrane recycling at the plasma membrane (D'Souza-Schorey et al., 1995; Peters et al., 1995). A clear-cut inhibitory effect of both normal and Rac1B-enhanced neuritogenesis could be observed by expressing mutants affecting the nucleotide cycle of Arf6. Corresponding mutants for Arf1 and Arf5, representatives of class I and class II Arfs, respectively, showed weaker inhibitory effects on neuritogenesis, indicating a prominent role of Arf6 in this process. These data also show that a cycling GTPase is required for neurite extension, as already observed for other GTPases implicated in the regulation of neuritogenesis (Luo, 2000). This requirement probably reflects the need for a cyclic mode of signaling, appropriate to a highly dynamic process such as neurite extension.

Arf proteins have very slow rates of GTP hydrolysis and require specific GAP proteins to be inactivated (Welsh et al., 1994). The Arf-GAP activity of GIT proteins on distinct Arf proteins, including Arf6, has been recently demonstrated in vitro (Vitale et al., 2000). The colocalization of the p95-APP1 mutants with Arf6 at endocytic vesicles, and the lack of evident colocalization of p95-APP1 with Arf1 indicate a specific role for p95-APP1 as a regulator for Arf6 in these neurons. Accordingly, although GIT2 has been recently shown to specifically affect Arf1-mediated βCOP distribution in nonneuronal cells (Mazaki et al., 2001), we could not detect any effect on βCOP distribution by overexpressing p95-APP1 in retinal cells. A partial overlap between p95-N and Arf5 was also observed. Like Arf1, Arf5 has been implicated in the regulation of traffic in the Golgi (Liang and Kornfeld, 1997), although recent findings suggest that Arf5 may also influence the same cellular pathways influenced by Arf6 through common effectors (Shin et al., 2001). In support of the functional connection between p95-APP1 and Arf6, we also detected a potentiation of neuritogenesis in cells coexpressing wild-type Arf6 and p95-C. This potentiation was not observed in neurons coexpressing either Arf1 or Arf5 with p95-C and could be prevented by expressing either p95-C2 with wild-type Arf6, or the dominant negative N27Arf6 with p95-C. Together, these data imply the requirement of Arf6 and p95-APP1 in membrane recycling. We would like to speculate that, like Arf1 in the Golgi (Roth, 1999), Arf6 regulates vesicle formation during recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane. Like the Arf1-specific ArfGAP protein in the Golgi (Goldberg, 1999), p95-APP1 would play a role in the regulation of these events at recycling endosomes. In this direction, it is interesting to observe that in retinal neurons accumulation of Arf6 at intracellular sites could be induced either by coexpressing the wild-type Arf6 protein with the ArfGAP-defective p95-C2 (or p95-K39) construct, or by expressing the GTP hydrolysis-defective mutant L67Arf6. In both cases, intracellular accumulation may be caused by the inability of Arf6 GTP to be converted into Arf6 GDP. The finding that L67Arf6 accumulates at perinuclear sites in retinal neurons is apparently in contrast with what was previously reported in nonneuronal cells (Peters et al., 1995), where the GTP hydrolysis-defective mutant was localized to the plasma membrane. This difference may be due to the different cellular systems analyzed in the two studies.

The finding that overexpression of the full-length ArfGAP p95-APP1 does not prevent Arf6-mediated neuritogenesis could be explained in different ways. P95 is a multidomain protein, probably undergoing complex spatial and temporal regulation. One would expect the effects of the full-length protein to be tightly regulated in the cell, so to have a functional protein only where and when it is necessary. This would also explain why ArfGAP proteins that show broad specificity in vitro have a more restricted specificity in vivo. Only a limited pool of p95-APP1 would be activated in the cell at any time in our system. If so, the differences observed in different cell systems may arise not only by the different levels of endogenous ArfGAP but also by different levels of the protein(s) regulating their function. Future work on the function and regulation of GIT proteins will help clarifying this point.

By considering the differences between p95-C and p95-C2 and the results obtained with the p95-ΔSHD mutant, our results show that both the lack of an active ArfGAP domain, and the presence of the PIX-binding domain are necessary for the accumulation of the p95-complex at enlarged Rab11-positive endosomes, and for the concomitant inhibition of neurite extension. It is therefore reasonable to implicate PIX in the recruitment of the p95-APP1 complex at the Rab11 compartment. According to our hypothesis, the combination of PIX-mediated recruitment of p95 at endocytic membranes, with the inability of ArfGAP mutants to regulate Arf6-mediated membrane recycling from the compartment, causes the accumulation of endocytic membranes at an abnormal Rab11-positive compartment, and the coincident inhibition of neurite formation.

Together, our analysis has identified a functional interplay between p95-APP1 and Arf6 during Rac1B-mediated neurite extension on laminin and has provided evidence for an important role of the p95-complex in the regulation of membrane traffic during neuritogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Annalisa Bolis, Barbara Sporchia, and Andrea Sironi for the preparation of the plasmids for the Arf proteins; Marino Zerial for the anti-Rab11 antibody; Harald Stenmark for the anti-EEA1 antibody; Ed Manser and Louis Lim for the pXJ40-HA-βPIX plasmid and the anti-PIX antibody; Gary Bokoch for the pCMV6 m/PAK1 plasmid; and Victor Hsu for the anti-Arf6 antibody. The mAb LEP100 developed by D.M. Fambrough was obtained by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank. We also thank Jacopo Meldolesi and Ruggero Pardi for critical reading of the manuscript. The financial support of Telethon-Italy grant GGP02190 (to I.deC.) is gratefully acknowledged. C.A. was supported by a fellowship from Italian Federation for Cancer Research. In collaboration with the Center of Excellence in Physiopathology of Cellular Differentiation.

Abbreviations used:

- Arf6

ADP-ribosylation factor 6

- ArfGAP

ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein

- CEFs

chicken embryo fibroblasts

- E6

embryonic day 6

- E10

embryonic day 10

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- SHD

Spa2 homology domain

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0406. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–07–0406.

Corresponding author. E-mail address: decurtis.ivan@hsr.it.

REFERENCES

- Adler R, Jerdan J, Hewitt AT. Responses of cultured neural retinal cells to substratum-bound laminin and other extracellular matrix molecules. Dev Biol. 1985;112:100–114. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertinazzi C, Gilardelli D, Paris S, Longhi R, de Curtis I. Overexpression of a neural-specific Rho family GTPase, cRac1B, selectively induces enhanced neuritogenesis and neurite branching in primary neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard V, Pohl BP, Bokoch GM. Characterization of Rac and Cdc42 activation in chemoattractant-stimulated human neutrophils using a novel assay for active GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13198–13204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AM, Wyborski RJ, Banker G. Preferential addition of newly synthesized membrane protein at axonal growth cones. Nature. 1995;375:592–594. doi: 10.1038/375592a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza-Schorey C, Li G, Colombo MI, Stahl PD. A regulatory role for ARF6 in receptor-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1995;267:1175–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.7855600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Curtis I. Cell migration: GAPs between membrane traffic and the cytoskeleton. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:277–281. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cesare A, Paris S, Albertinazzi C, Dariozzi S, Andersen J, Mann M, Longhi R, de Curtis I. p95-APP1 links membrane transport to Rac-mediated reorganization of actin. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:521–530. doi: 10.1038/35019561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach TJ, Guthrie PB, Stier H, Billups B, Kater SB. Membrane recycling in the neuronal growth cone revealed by FM1-43 labeling. J Neuroscience. 1999;19:9436–9444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09436.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson JG, Jackson CL. Regulators and effectors of the ARF GTPases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:475–482. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fambrough DM, Takeyasu K, Lippincott-Schwarz J, Siegel NR. Structure of LEP100, a glycoprotein that shuttles between lysosomes and the plasma membrane, deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the encoding cDNA. J Cell Biol. 1988;106:61–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaschet J, Hsu VW. Distribution of ARF6 between membrane and cytosol is regulated by its GTPase cycle. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20040–20045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg J. Structural and functional analysis of the ARF1-ARFGAP complex reveals a role for coatomer in GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 1999;96:893–902. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80598-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haataja L, Groffen J, Heisterkamp N. Characterization of Rac3, a novel member of the Rho family. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20384–20388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson TR, Brown FD, Nie Z, Miura K, Foroni L, Sun J, Hsu VW, Donaldson JG, Randazzo PA. ACAPs are ARF6 GTPase-activating proteins that function in the cell periphery. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:627–638. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrach H, Diamond D, Wozney JM, Boedtker H. RNA molecular weight determinations by gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions, a critical reexamination. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4743–4751. doi: 10.1021/bi00640a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang JO, Kornfeld S. Comparative activity of ADP-ribosylation factor family members in the early steps of coated vesicle formation on rat liver Golgi membranes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4141–4148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L. Rho GTPases in neuronal morphogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:173–180. doi: 10.1038/35044547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malosio ML, Gilardelli D, Paris S, Albertinazzi C, de Curtis I. Differential expression of distinct members of the Rho family of GTP-binding proteins during neuronal development: identification of Rac1B, a new neural-specific member of the family. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6717–6728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06717.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandiyan V, Andreev J, Schlessinger J, Hubbard SR. Crystal structure of the ARF-GAP domain and ankyrin repeats of PYK2-associated protein β. EMBO J. 1999;18:6890–6898. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manser E, Loo TH, Koh CG, Zhao ZS, Chen XQ, Tan L, Tan I, Leung T, Lim L. PAK kinases are directly coupled to the PIX family of nucleotide exchange factors. Mol Cell. 1998;1:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaki Y, et al. An ADP-ribosylation factor GTPase-activating protein Git2-short/KIAA0148 is involved in subcellular localization of paxillin and actin cytoskeletal organization. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:645–662. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.3.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matafora V, Paris S, Dariozzi S, de Curtis I. Molecular mechanisms regulating the subcellular localization of p95-APP1 between the endosomal recycling compartment and sites of actin organization at the cell surface. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4509–4520. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris S, Za L, Sporchia B, de Curtis I. Analysis of the subcellular distribution of avian p95-APP2, an ARF-GAP orthologous to mammalian paxillin kinase linker. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:826–837. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters PJ, Hsu VW, Ooi CE, Finazzi D, Teal SB, Oorschot V, Donaldson JG, Klausner RD. Overexpression of wild-type and mutant ARF1 and ARF6: distinct perturbations of nonoverlapping membrane compartments. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:1003–1017. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris R, Foletti DL, Scheller RH. Dynamics of tubulovesicular recycling endosomes in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10324–10337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10324.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna H, Al-Awar O, Khachikian Z, Donaldson JG. ARF6 requirement for Rac ruffling suggests a role for membrane trafficking in cortical actin rearrangements. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:855–866. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.6.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna H, Klausner RD, Donaldson JG. Aluminum fluoride stimulates surface protrusions in cells overexpressing the ARF6 GTPase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:935–947. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randazzo PA, Andrade J, Miura K, Brown MT, Long Y-Q, Stauffer S, Roller P, Cooper JA. The ARF GAP ASAP1 regulates the actin cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4011–4016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070552297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren M, Xu G, Zeng J, De Lemos-Chiarandini C, Adesnik M, Sabatini DD. Hydrolysis of GTP on rab11 is required for the direct delivery of transferrin from the pericentriolar recycling compartment to the cell surface but not from sorting endosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6187–6192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein Rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesion and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell. 1992;70:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth MG. Snapshots of ARF1: implications for mechanisms of activation and inactivation. Cell. 1999;97:149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin OH, Couvillon AD, Exton JH. Arfophilin is a common target of both class II and class III ADP-ribosylation factors. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10846–10852. doi: 10.1021/bi0107391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen A, Lippe R, Christoforidis S, Gaullier JM, Brech A, Callaghan J, Toh BH, Murphy C, Zerial M, Stenmark H. EEA1 links PI(3)K function to Rab5 regulation of endosome fusion. Nature. 1998;394:494–498. doi: 10.1038/28879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen B, De Renzis S, Nielsen E, Rietdorf J, Zerial M. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szafer E, Pick E, Rotman M, Zuck S, Huber I, Cassel D. Role of coatomer and phospholipids in GTPase-activating protein-dependent hydrolysis of GTP by ADP-ribosylation factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23615–23619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka E, Sabry J. Making the connection: cytoskeletal rearrangements during growth cone guidance. Cell. 1995;83:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl R, Rhode H, Gehron-Robey P, Rennard S, Foidart JM, Martin G. Laminin, a glycoprotein from basement membrane. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9933–9937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CE, Brown MC, Perrotta JA, Riedy MC, Nikolopoulos SN, McDonald AR, Bagrodia S, Thomas S, Leventhal PS. Paxillin LD4 motif binds PAK and PIX through a novel 95-kD ankyrin repeat, ARF-GAP protein: a role in cytoskeletal remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:851–863. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich O, Reinsch S, Urbe S, Zerial M, Parton RG. (1996). Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitale N, Patton WA, Moss J, Vaughan M, Lefkowitz RJ, Premont RT. GIT proteins, a novel family of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-stimulated GTPase-activating proteins for ARF6. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13901–13906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh CF, Moss J, Vaughan M. Isolation of recombinant ADP-ribosylation factor 6, a 20-kDa guanine nucleotide-binding protein, in an activated GTP-bound state. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15583–15587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]