Abstract

A ubiquitous feature of collagens is protein interaction, the trimerization of monomers to form a triple helix followed by higher order interactions during the formation of the mature extracellular matrix. The Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle is a complex extracellular matrix consisting predominantly of cuticle collagens, which are encoded by a family of ∼154 genes. We identify two discrete interacting sets of collagens and show that they form functionally distinct matrix substructures. We show that mutation in or RNA-mediated interference of a gene encoding a collagen belonging to one interacting set affects the assembly of other members of that set, but not those belonging to the other set. During cuticle synthesis, the collagen genes are expressed in a distinct temporal series, which we hypothesize exists to facilitate partner finding and the formation of appropriate interactions between encoded collagens. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find for the two identified interacting sets that the individual members of each set are temporally coexpressed, whereas the two sets are expressed ∼2 h apart during matrix synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

During postembryonic development, Caenorhabditis elegans is enclosed within a cuticle (Cox et al., 1981a,b; Johnstone, 1994; Kramer, 1994, 1997). The cuticle is an extracellular matrix (ECM) that is a barrier between the animal and its environment and is essential for body morphology (Kramer et al., 1988; von Mende et al., 1988; Johnstone et al., 1992). It is synthesized by an underlying ectodermal cell layer termed the hypodermis that surrounds the body of the animal (Figure 1). During synthesis, material is secreted from the apical membranes of the hypodermis and then polymerizes on the outer surface of the membranes where it remains in intimate contact as the mature cuticle. Synthesis occurs five times during development, once in the embryo and then before molting at the end of each larval stage. Thus, with the exception of the first round of synthesis, synthesis occurs underneath an existing cuticle and requires its displacement from the membrane surface before, or concurrent with, secretion and polymerization of the new cuticle (Figure 1C). The old cuticle is removed by molting (Singh and Sulston, 1978).

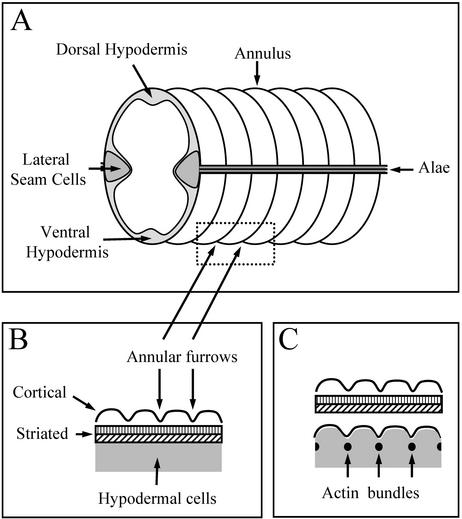

Figure 1.

Cuticular structures in C. elegans. (A) Diagram of a section of a C. elegans adult showing cuticular structures (annuli and alae) and a cross section of the underlying hypodermal cells. (B) Diagram of a longitudinal cross section through the cuticle and hypodermis, indicating the location of the annular furrows in the outer cortical layer of the cuticle. (C) Cross section as in B but during cuticle synthesis, with a new outer cortical layer underneath a displaced old cuticle, showing the position of the transient circumferential actin bundles in the hypodermal cells and the associated furrows above these bundles on the hypodermal membrane surface. Note the juxtaposition of these bundles, the furrows in the hypodermal apical membrane, and the annular furrows in the newly formed cortical layer.

This ECM has a multilayered ultrastructure (Cox et al., 1981b; Peixoto and Desouza, 1995; Peixoto et al., 1997) and consists predominantly of small collagens that are encoded by a family of ∼154 genes. The cuticle collagens have short interrupted blocks of Gly-X-Y sequence flanked by conserved cysteine residues and can be grouped into families according to homology (Johnstone, 2000). In structure and size, they are most similar to the fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices (FACIT) collagens of vertebrates.

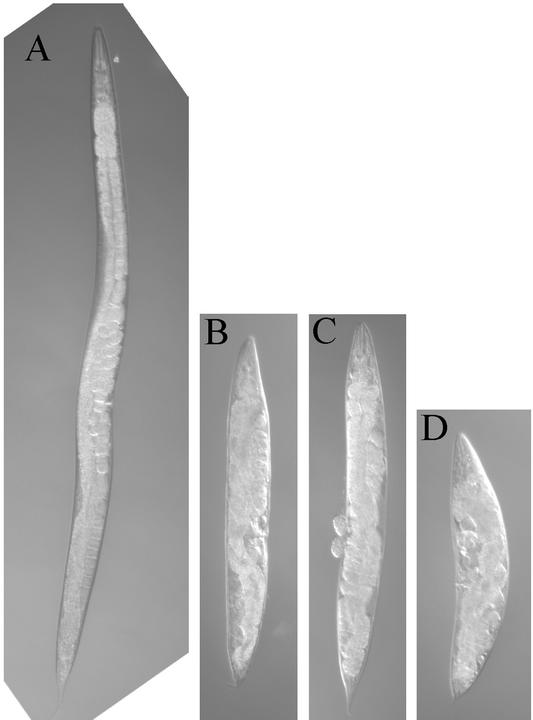

For a small number of the cuticle collagen genes, loss-of-function or reduced-function alleles have been identified that cause a change in body shape (von Mende et al., 1988; Levy et al., 1993; Johnstone, 1994), indicating specific functions for the products of these genes. Genes for which loss-of-function alleles give severe exoskeletal defects must be critical to assembly or function of this ECM. Seven cuticle collagen genes have been identified (two herein) for which homozygous reduced or loss-of-function alleles result in a phenotype described as dumpy (Dpy); mutant animals are shorter and fatter than wild-type animals (Figure 2). Among these genes, dpy-7 and dpy-8 encode products that are closely related by sequence, as are the dpy-2 and dpy-10 products. The products of dpy-3, dpy-5, and dpy-13 are not closely related to one another or to either of the two pairs. There is no obvious feature that distinguishes those collagen genes that are mutable to the Dpy phenotype from the other cuticle collagen genes.

Figure 2.

Dpy phenotype. Images of adult hermaphrodites are shown at the same magnification. (A) Wild-type strain N2. (B) dpy-7(qm63) mutant. (C) dpy-13(e458) mutant. (D) dpy-13(e458);dpy-7(qm63) double mutant.

During each cuticle synthetic period, the cuticle collagen genes are expressed in a distinct temporal series, the pattern of which is repeated at each synthetic period (Johnstone and Barry, 1996). According to their time of expression within this series, the cuticle collagen genes can be described as early, intermediate, or late, corresponding to peaks of mRNA abundance at approximately 4 h before, 2 h before, and concurrent with secretion of each new cuticle, respectively. The dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-7, dpy-8, and dpy-10 genes are early expressed, whereas the dpy-5 and dpy-13 genes are intermediate expressed.

The outer layer of the C. elegans cuticle is patterned at all developmental stages with circumferential ridges termed annuli; longitudinal ridges termed alae are present on the cuticle of the L1 and dauer larvae and of the adult (Figure 1; see also Figures 4C and 5A) (Cox et al., 1981a; Johnstone, 2000). During cuticle synthesis, submembranous actin filaments form within the hypodermal cells and are organized circumferentially around the cylindrical body of the worm (Figure 1C), coincident with the furrows that form on the apical surface of the hypodermal cell membrane during cuticle synthesis and subsequently with the furrows that delineate the boundaries of the annuli on the surface of the polymerized cuticle (Figure 1) (Costa et al., 1997). The inner layers of the cuticle are secreted underneath the outer layer, displacing the contact of the newly synthesized outer layer from the membrane surface. The presence of the actin filaments and the furrows that they produce on the surface of the hypodermal membrane are transient; they are no longer present when the inner layers of the cuticle, which are not patterned by furrows, polymerize. The furrows remain in the outer layer of the cuticle, indicating that once polymerization has occurred, their presence does not require the continued presence of the actin bundles in the underlying hypodermal cells.

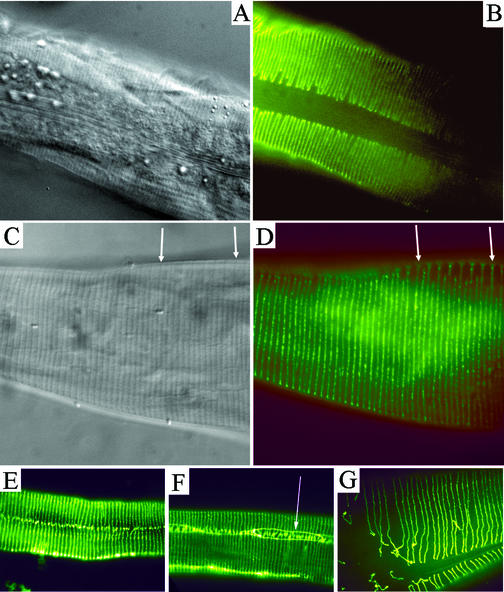

Figure 4.

Immunolocalization of DPY-7 in the cuticle of larval and adult stages. (A–D) Nomarski (A and C) and fluorescence (B and D) images of two adults. A and B are in the some focal plane, as are C and D; C and D are at higher magnification. The alae are visible in A, running left to right across the specimen. The annuli are at right angles to the alae and extend to the edges of the animal. White arrows, a region of the cuticle where the regular spacing of the annuli is disrupted; every second delineating furrow is absent. The DPY-7 bands are seen to locate to the furrows. (E and F) Midstage larvae (L2 or L3), which do not have alae, stained with the DPY7-5a mAb (E) or double stained with the DPY7-5a and MH27 mAbs (F). White arrow, the boundary of an underlying seam cell detected with MH27. (G) DPY7-5a localization in an adult fixed by the modified Ruvkun method involving partial reduction of the specimen. The thread-like nature of the DPY-7 bands after partial reduction is evident.

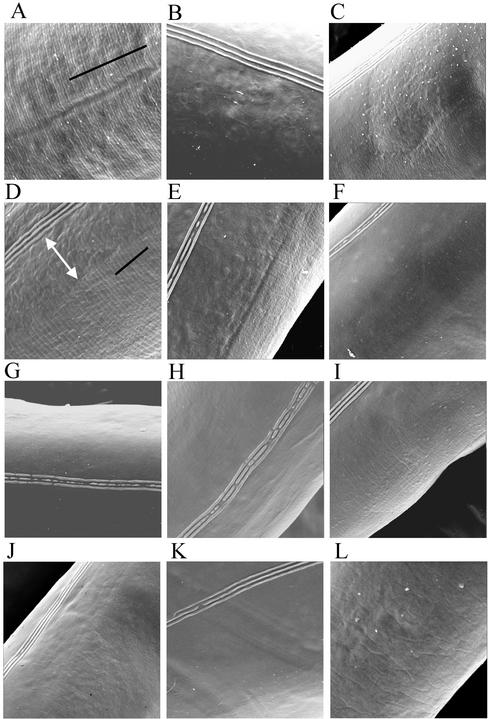

Figure 5.

Scanning electron micrographs of the surfaces of adult wild-type and mutant worms. A–K are at the same magnification; L is at twice this magnification. (A) Wild-type strain N2. (B) dpy-7(qm63). (C) dpy-7(e88). (D) dpy-13(e458). (E) dpy-2(e1359). (F) dpy-2(e8). (G) dpy-3(e27). (H) dpy-8(e130). (I) dpy-8(sc44). (J) dpy-10(sc48). (K) dpy-10(e128). (L) sqt-1(e1350). Alae are visible in most images as three distinct parallel lines; annuli are visible in A and D, running perpendicular to the black lines that indicate the span of ten annuli. The white arrow in D indicates the region close to the alae on the dpy-13(e458) mutant where annuli are disorganized in comparison with wild type.

Herein, we investigate the synthesis and interaction of the DPY collagens and identify two discrete ECM substructures formed by two discrete interacting sets of collagens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

C. elegans culture was by standard methods (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988). Some strains were obtained from the C. elegans Genetics Stock Center (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN), which is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources. The strain MQ375 was a gift from Jonathan Ewbank (Centre d'Immunologie de Marseille-Luminy, Marseille, France) and Siegfried Hekimi (McGill University, Montreal, PQ, Canada). The following strains were used: N2 Bristol wild-type, BE93 dpy-2(e8), BE38 dpy-2(sc38), CB1359 dpy-2(e1359), CB27 dpy-3(e27), CB61 dpy-5(e61), MQ375 dpy-7(qm63), CB88 dpy-7(e88), CB130 dpy-8(e130), BE44 dpy-8(sc44), CB1282 dpy-8(e1281), CB128 dpy-10(e128), SP399 dpy-10(sc48), TN64 dpy-10(cn64), CB184 dpy-13(e148), CB458 dpy-13(e458), CB1350 sqt-1(e1350), CB4121 sqt-3(e2117), and DR518 rol-6(su1006).

DPY-7 Monoclonal Antibody (mAb)

Recombinant DPY-7 protein fragments were generated in Escherichia coli by using the QIAGEN (Crawley, United Kingdom) vector pQE-30, according to standard manufacturer's protocol. A DPY-7 fragment constituting most of the predicted mature protein was used to immunize mice, and monoclonal cell lines were generated by fusing splenocytes to Sp2/O-Ag14 myeloma cells by using standard methods (Harlow and Lane, 1988). The cell line DPY7-5a was selected for use based on the sensitivity and specificity of the antibody for the DPY-7 protein. It reacts to an epitope within the 40 carboxy-terminal non-Gly-X-Y residues of the protein.

Cloning dpy-3 and dpy-8

Genetic mapping data generated by other laboratories and curated by WormBase (http://www.wormbase.org/) were used to facilitate the positional cloning of the genes dpy-3 and dpy-8, both of which are on the X chromosome. dpy-3 maps between the polymorphism meP2 and the gene lin-32, which positions dpy-3 between cosmids C31C1 and T14F9 on the physical map. There are two predicted cuticle collagen genes within this interval, T21D9.1 and EGAP7.1. dpy-8 maps between the gene npr-1 and the polymorphism stP156, which positions it between cosmids C39E6 and F35C8. C31H2.2 is the only predicted cuticle collagen gene within this interval.

We tested the ability of cosmid clone T21D9 and plasmid clone EGAP7 to rescue the dpy-3 mutant phenotype and the ability of the cosmid clone C31H2 to rescue the dpy-8 mutant phenotype. We found that EGAP7 rescues efficiently the dpy-3(e27) phenotype and C31H2 rescues efficiently the dpy-8(e130) phenotype, by transgenesis. We did not obtain rescue of the dpy-3 phenotype with T21D9. To test whether the predicted cuticle collagen genes contained within the clones EGAP7 and C31H2 were sufficient to rescue mutant phenotype, we subcloned the predicted cuticle collagen genes EGAP7.1 and C31H2.2. DNA fragments from respective clones were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and subcloned into standard PCR cloning vectors (see Supplementary Material). The EGAP7.1 clone contains 1.38 kb of upstream and 0.8 kb of downstream gene sequence. The C31H2.2 clone contains 1.1 kb of upstream and 0.3 kb of downstream sequence. No other intact predicted genes are contained within these clones. Phenotypic rescue of dpy-3(e27) and dpy-8(e130) was achieved by transgenesis with the EGAP7.1 and C31H2.2 clones, respectively.

Ty-tagged Gene Fusions

The dpy-7, dpy-10, and dpy-13 clones used for this work contained sufficient 3′- and 5′-genomic sequence to elicit functional expression of each gene in transgenic C. elegans strains. The clones used were tested for functionality by transforming them into respective mutant strains (CB88 for dpy-7, CB128 for dpy-10, and CB458 for dpy-13). Transgenes of each clone efficiently rescue the respective mutant phenotype.

A HindIII restriction site was generated in the dpy-7, dpy-10 and dpy-13 gene clones, immediately 3′ of the region that encodes the amino-terminal conserved cysteine residues termed domain I (Johnstone, 2000). This site was used for insertion of annealed oligonucleotides TyA 5′-AGCTTGAGGTCCATACTAACCAAGATCCACTTGACA-3′ and TyB 5′-AGCTTGTCAAGTGGATCTTGGTTAGTATGGACCTCA-3′, which encode the Ty epitope tag (Bastin et al., 1996). Clones were sequenced to check for correct orientation of inserted Ty oligonucleotides. The Ty-tagged versions of the clones were tested for functionality by transforming the respective mutants and rescued mutant phenotype as effectively as the nontagged parental clones. Details regarding construction of the clones are given in Supplementary Material.

RNA Interference

RNA-mediated interference (RNAi) was performed by the bacterial feeding method (Timmons et al., 2001) with E. coli strain HT115. PCR products of genes were generated using the following oligonucleotides: dpy-5 (5′-GTCTGCGCTTTCTCTCTGGG-3′ and 5′-GCTGCATGCGGAATCTCTGC-3′), dpy-7 (5′-CCACCACGTGCTGGCTTCTC-3′ and 5′-CCACGTGGCAAAAGCCACCG-3′), and dpy-10 (5′-GATCTACCGGTGTGTCACCG-3′ and 5′-CCCATTGGTCCTTCTGGTCC-3′).

Products were cloned into the double T7 RNAi feeding vector L4440 (Timmons et al., 2001). RNAi was performed by placing C. elegans embryos on RNAi plates and allowing the animals to grow to adults on the plates, cultured at 20°C. For each gene tested, the RNAi effect on the wild-type strain N2 was similar to that of strong loss-of-function mutations in the respective gene.

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

Timing of collagen gene expression was determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR by using RNA samples generated from time points throughout postembryonic C. elegans development, as described previously (Johnstone and Barry, 1996). The following modifications to the published method were used. PCR cycling was performed for 32 cycles; amplified products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Digital images of the gels were taken using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Gel Doc 2000 system. Pixel densities of imaged amplified bands were measured using Scion Image for Windows, Beta release 4.0.2, which is available free from Scion (Frederick, MD) and is based on NIH Image for Macintosh. For each time point, the ratio of the number of pixels representing the amplified test gene band and the amplified control gene ama-1 band was determined. This provides a semiquantitative estimate of relative abundance of test gene mRNA to control ama-1 gene mRNA at each time point, which can then be plotted graphically.

The timing of expression of the genes dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-5, dpy-8, and dpy-10 was determined using these methods. Primers used for RT-PCR were ama-1 (5′-CAGTGGCTCATGTCGAGTTTCCAGA-3′ and 5′-CGACCTTCTTTCCATCATTCATCGG-3′), dpy-2 (5′-TATCAAGTTCTGATTGCCGTTTCCG-3′ and 5′-GCAGCCAGCATTGATGGATTATAATGT-3′), dpy-3 (5′-ATCACGACGTGTGCGACGAGC-3′ and 5′-GCAGAAATGCGCCCCACGG-3′), dpy-5 (5′-GC-TGCATGCGGAATCTCTGC-3′ and 5′-GTCTGCGCTTTCTCTCTGGG-3′), dpy-8 (5′-AGTCTTCTTTGAAGCAACTTCTTGCGC-3′ and 5′-CAGTAAATGCTCCAGAATACGGAGACG-3′), and dpy-10 (5′-TCCTGGACATTCAGTTTCAAGTGGAGC-3′ and 5′-ACCGGTCTTCAAATCGGATTTAGCTTA-3′).

Immunolocalization

The general method used for fixation of all developmental stages of C. elegans before immunolocalization was freeze fracture on slides followed by methanol and acetone fixation at −20°C (Miller and Shakes, 1995). The only exception was in Figure 4G, where fixation was by the modified Finney and Ruvkun method (Miller and Shakes, 1995), which uses partial reduction in a solution containing 1% mercaptoethanol to permeablize the cuticle. A 2-h treatment in this solution generates a high proportion of animals with the appearance of that in Figure 4G. In all cases, immunolocalization was by standard methods with milk as a blocking agent (Miller and Shakes, 1995). Both the DPY7-5a monoclonal and anti-Ty tag monoclonal antibodies were concentrated before use from respective monoclonal cell line culture supernatant by ammonium sulfate precipitation (Harlow and Lane, 1988). The anti-Ty tag monoclonal cell line was a gift from Keith Gull (University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom), LIN-26 antibody was a gift from Michel Labouesse (IGBMC CNRS/INSERM/ULP, Strasbourg, France), and MH27 mAb was a gift from Robert Waterston (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO). Secondary antibodies conjugated to various fluorescent labels were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Microscopy

Immunofluorescence and Nomarski microscopy used standard methods (Sulston and Hodgkin, 1988; Miller and Shakes, 1995). Images were captured digitally using Openlab imaging software (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom), and figures were prepared using Adobe Photoshop.

For scanning electron microscopy, animals were fixed for 1.5 h on ice in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). They were rinsed three times in phosphate buffer and 2% sucrose before postfixing in 1% osmium tetroxide in distilled water for 1 h followed by three 10-min washes in distilled water. They were incubated in the dark for 1 h in 0.5% uranyl acetate and then washed further in distilled water. Fixed animals were then dehydrated in acetone, critical point dried in CO2, mounted on stubs, coated with gold (Polaron SC515), and examined in a Phillips SEM500 scanning electron microscope.

RESULTS

Localization of DPY-7 in C. elegans Embryo

The DPY-7 cuticle collagen is predicted to have a carboxy-terminal domain of 40 residues that is not shared with other C. elegans cuticle collagens. Thus, we generated a mouse mAb DPY7-5a reactive to this domain. From the evidence below, we believe that this domain is present in the mature DPY-7 collagen and that the DPY7-5a mAb recognizes specifically the DPY-7 collagen.

Previous studies using green fluorescent protein (GFP) and lacZ reporter transgenes have indicated that the dpy-7 collagen gene is transcribed in hypodermal cells from about the comma stage of embryogenesis at the start of embryonic elongation (Johnstone and Barry, 1996; Gilleard et al., 1997). dpy-7::GFP and dpy-7::lacZ reporter transgenes are expressed in most, and possibly all, hypodermal cells (Gilleard et al., 1997). Because there is no preexisting cuticle in the developing embryo, the newly synthesized collagen can be observed before secretion within the synthesizing cells by immunofluorescence detection with the DPY7-5a mAb. Intracellular localization of DPY-7 is first observed at the comma stage of embryogenesis (Figure 3A), which corresponds to ∼4 h before secretion of the L1 cuticle, concurring with the known temporal pattern of expression of dpy-7 (Johnstone and Barry, 1996). The staining remains intracellular through the later stages of embryogenesis, and the first evidence of secretion of DPY-7 is at the threefold stage (Figure 3B). Extracellular staining within the secreted cuticle is seen at the late threefold stage of embryogenesis just before hatch (Figure 3C). DPY-7 location within the cells is detected as a halo surrounding the nucleus (Figure 3, A and G). This perinuclear pattern is consistent with location in a secretary pathway organelle, probably the endoplasmic reticulum.

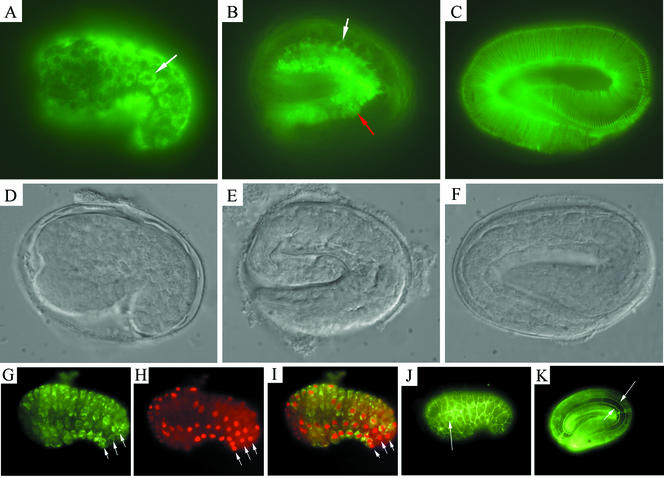

Figure 3.

Immunolocalization of DPY-7 in C. elegans embryos. (A–F) DPY-7 localization in a comma stage embryo (A), a threefold embryo during cuticle secretion (B), and a late threefold embryo after cuticle secretion (C). (D–F) Nomarski images of the same embryos. In A, nuclei are seen as nonstained circles surrounded by a halo of DPY-7 fluorescence (white arrow). In B, some extracellular localized DPY-7 (red arrow) and some remaining perinuclear-localized DPY-7 (white arrow) are both seen. This animal seems to be in the process of secreting DPY-7. In C, secretion seems to be complete, with DPY-7 being detected in mature circumferential stripes. (G–I) Embryo double labeled with the DPY7-5a mAb (G and I) and anti-LIN-26 polyclonal antibody (H and I). LIN-26 is present in all hypodermal cell nuclei at this stage. White arrows, the three rows of cells that make up the main body hypodermis of one side of the animal are indicated: P cells that form the ventral hypodermis (bottom row); V cells that form the lateral seam (middle row); hyp-7 cells that form the main body hypodermal syncytium (top row). (J and K) Comma-stage embryo (J) and a late threefold embryo after cuticle secretion (K) double stained with DPY7-5a and MH27 mAbs. The hypodermal cell boundaries are visualized as thin lines by MH27 detection of adherens junctions. Arrow in J, the nucleus of one of the seam cells; the halo of DPY-7 localization is visible around it. By the late threefold stage, the hypodermal cells have elongated and the cuticle has polymerized on the hypodermal surface; arrows in K indicate the dorsal and ventral boundaries of an elongated seam cell.

To assist in the identification of cells, the antibodies MH27 (Francis and Waterston, 1991) and anti-LIN-26 (Labouesse et al., 1994) were used to visualize hypodermal cell junctions and nuclei of hypodermal cells, respectively. The DPY-7 protein is detected during embryogenesis in most and probably all hypodermal cells, and certainly within the hyp-7 cells that form the major body hypodermal syncytium, the P cells that form the ventral hypodermis, and the V cells that constitute the lateral seam (Figure 3, G–J). Although DPY-7 is synthesized in all major hypodermal cells, the mature secreted collagen is only detected on the apical surfaces of the dorsal and ventral hypodermal cells and not on the lateral surface above the seam cells of developmental stages that have alae (see below). This absence was shown by costaining with the MH27 antibody to delineate the boundaries of the seam cells (Figure 3K).

Localization of DPY-7 within Cuticle

The DPY-7 protein is detected in circumferential bands within the cuticle of each larval stage and the adult (Figure 4). The DPY-7 bands locate within the furrows that delineate the annuli (Figure 4, C and D). The DPY-7 bands are not continuous around the entire worm body. In the adult and the L1 larva, longitudinal ridges termed alae exist within the cuticle above the seam cells (Singh and Sulston, 1978). We do not detect DPY-7 within these ridges or the matrix region immediately surrounding them (Figure 4B). In larval stages with no alae, the DPY-7 bands start and end above the lateral seam cells where they partly interdigitate (Figure 4, E and F).

The cuticle collagens are cross-linked by both reducible and nonreducible covalent bonds. When a partial reduction step is included during fixation for immunostaining, the DPY-7–containing bands dissociate from other ECM material and adopt a discrete thread-like appearance (Figure 4G). The DPY-7 bands seem to be more resistant to reduction than the ECM material that lies between the bands. We conclude that the DPY-7 collagen is assembled into tight band or thread-like structures that run circumferentially around the body of the animal, located within the furrows that delineate the annuli.

DPY-7 Collagen Is an Essential Component of Annular Furrows

We next observed the cuticle surface of wild-type and mutant animals to determine whether the observable structure of the annuli is affected by loss of dpy-7. In adult wild-type animals, annuli are visible by scanning electron microscopy (Figure 5A). In adults of the null mutant dpy-7(qm63), the dorsal and ventral cuticle surfaces are smooth and completely lacking annuli (Figure 5B). For the glycine substitution mutant dpy-7(e88) (see below), these surfaces lack regularly patterned annuli, but are creased or dimpled (Figure 5C). Thus, the DPY-7 collagen is essential for the presence or persistence of the furrows that delineate the annuli. It is not required for alae, which are present on the cuticles of both dpy-7(qm63) and dpy-7(e88) adults (Figure 5, B and C).

No staining with the DPY7-5a mAb was detected in animals homozygous for the dpy-7(qm63) null allele (our unpublished data), supporting the specificity of this reagent. We tested DPY-7 immunolocalization in a homozygous dpy-7(e88) strain. This lesion was characterized previously and causes a glycine-to-arginine substitution at residue 156 (G156R) (Johnstone et al., 1992), within the Gly-X-Y domains. Within the embryo, the presecreted localization of the DPY-7(G156R) mutant collagen was indistinguishable from wild type (our unpublished data).

However, we found both qualitative and quantitative differences in the assembly of this mutant collagen into the cuticle. In contrast to the continuous DPY-7 bands of the wild type (Figure 6A), the DPY-7(G156R) collagen was seen in small disjointed fragments (Figure 6B). Although it is not possible to measure accurately the abundance of a protein by its immunofluorescence detection in a fixed specimen, longer imaging exposure times were required to detect the mutant DPY-7(G156R) protein assembled in the cuticle, indicating that it is less abundant than the wild-type protein within the ECM. Thus, we conclude that the DPY-7(G156R) mutant collagen accumulates within the synthetic hypodermal cells with an abundance similar to that in wild-type, but that it is not assembled efficiently into the mature ECM. Moreover, that which is polymerized seems to assemble aberrantly. Consistent with the proposed role of DPY-7 in furrow assembly, the fragmented pattern of mutant DPY-7(G156R) within the cuticle corresponds well with the irregular dimpled cuticle surface of this mutant (Figure 5C) and contrasts with the completely smooth surface of the dpy-7(qm63) null mutant (Figure 5B) and the regularly spaced furrows of the wild type (Figure 5A).

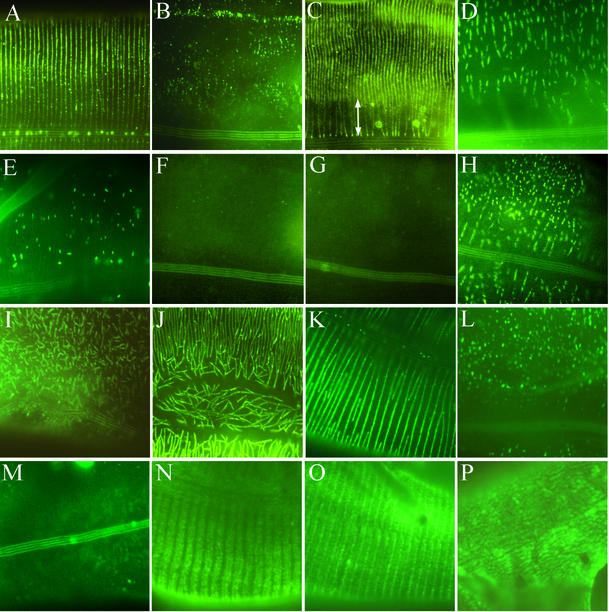

Figure 6.

Immunolocalization of the DPY-7, DPY-10, and DPY-13 collagens in adults of the various genetic backgrounds. (A–J) DPY-7 visualized with the DPY7-5a mAb in wild-type (A), dpy-7(e88) (B), dpy-13(e458) (C), dpy-2(sc38) (D), dpy-3(e27) (E), dpy-8(e130) (F), dpy-10(e128) (G), dpy-10(sc48) (H), sqt-1(e1350) (I), and sqt-3(e2117) (J) animals. In C, the region adjacent to the alae where the DPY-7 stripes are disorganized in the dpy-13(e458) mutant, is indicated by a white arrow. In B, E, F, and G, extended exposures were required to visualize the relatively faint fluorescent signals. (K–M) Transgenic epitope-tagged DPY-10::Ty visualized with the anti-Ty antibody in a dpy-10(e128) mutant (K) (note phenotypic rescue by the transgene), a dpy-7(e88) mutant (L), and a dpy-7(qm63) null mutant (M). In L and M, extended exposures were used in attempting to detect any faint DPY-10::Ty signal; the long exposure led to the visualization of background fluorescence from the alae in M. (N–P) Visualization of DPY-13::Ty and DPY-7 (O) in dpy-13(e458) animals in which the mutant phenotype is rescued by transgenic expression of dpy-13::Ty. In O, both primary antibodies were detected with the same secondary antibody. In P, the animal had been treated with dpy-7 RNAi.

Cloning of dpy-3 and dpy-8

Of the ∼154 cuticle collagen genes in C. elegans, only a few are mutable to generate the Dpy phenotype (see INTRODUCTION). We were interested to determine whether any of the other cuticle collagen genes that give a Dpy phenotype encode collagens that contribute to the formation of the same structure as DPY-7. The genes dpy-2, dpy-5, dpy-10, and dpy-13 have previously been cloned and shown to encode cuticle collagens. Cloning of dpy-3 and dpy-8 has not been reported, but we observed that these genes mapped close to predicted cuticle collagen genes identified by the C. elegans genome project. We therefore cloned these genes by standard methods (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). We found that dpy-3 corresponds to predicted cuticle collagen gene EGAP7.1 and dpy-8 to C31H2.2. The identification of dpy-8 as C31H2.2 was interesting because DPY-8 has the highest sequence similarity to DPY-7 of all other C. elegans cuticle collagens.

Timing of Expression of dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-5, dpy-8, and dpy-10

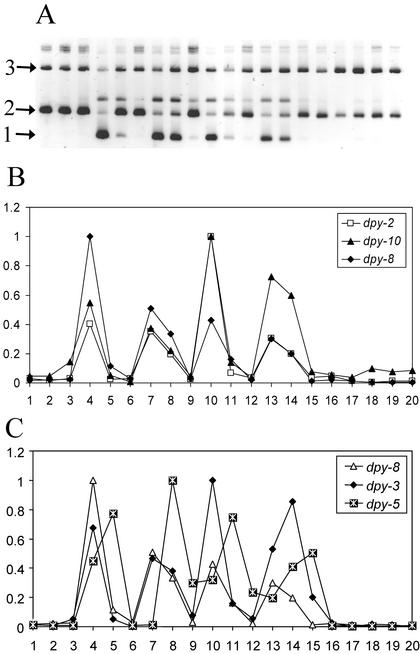

As determined previously (Johnstone and Barry, 1996), dpy-7 and dpy-13 are early- and intermediate-expressed cuticle collagen genes, whose mRNA abundances peak at ∼4 and ∼2 h before cuticle secretion, respectively. Using a modified version of the previously published method and reagents (see MATERIALS AND METHODS), we determined the timing of expression of the other dpy collagen genes (Figure 7). We found that dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-8, and dpy-10 are all temporally coexpressed with dpy-7, with the mRNA abundances of all five genes peaking at ∼4 h before each cuticle secretion. In contrast, dpy-5 is expressed concurrently with dpy-13, with its mRNA abundance peaking at ∼2 h before each cuticle secretion. Thus, the dpy cuticle collagen genes can be grouped into two discrete sets, early and intermediate, based on their times of expression relative to matrix synthesis.

Figure 7.

Timing of expression of the dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-5, dpy-8, and dpy-10 genes. The results of semiquantitative RT-PCR for the cuticle collagen genes dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-5, dpy-8, and dpy-10, performed on a time course of RNA samples taken at 2-h intervals from early Ll to young adult, displayed from left to right in the figures. Molts occurred during the time points represented by samples 6 (L1 to L2), 9 (L2 to L3), 12 (L3 to L4), and 15–16 (L4 to adult). (A) Negative image of an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel of the RT-PCR samples for dpy-8. The bands labeled 1 and 2 are amplified dpy-8 cDNA and genomic dpy-8 sequences, respectively. The RNA samples used are contaminated to various extents with genomic DNA, but amplification across an intron allows amplified cDNA and genomic DNA to be distinguished by size. In samples where a cDNA species is abundant, reduced amplification of the relevant contaminating genomic band is generally seen, as a result of competition for oligonucleotides. Bands labeled 3 are amplified control ama-1 cDNA. (B and C) Graphs showing relative transcript abundances, generated from data like those of A (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). (B) dpy-2, dpy-8, and dpy-10. (C) dpy-8, dpy-3, and dpy-5. In each cycle, the dpy-5 peak is one sample later than those for the other genes.

Interaction between DPY-7 and Other Cuticle Collagens

We next tested the localization of DPY-7 in the other dpy mutant backgrounds. We found in mutants of dpy-13 or dpy-5 that DPY-7 was assembled into bands of relatively normal appearance on the surface of the dorsal and ventral hypodermis (Figure 6C and Table 1); however, these bands were about half as far apart as in wild type. Consistent with these observations, scanning electron micrographs of the cuticle surface of dpy-5 and dpy-13 mutants showed that the furrows, and hence annuli, were present but narrower than in wild type (Figure 5D; our unpublished data). From measurements in the central body region of several animals, we estimated an average breadth of an annulus for fully grown adults of ∼1.5 μm for wild-type and 0.7 μm for dpy-13(e458) animals. The average breadth of annuli in young adults is significantly less in each case; the annuli stretch during adult life, presumably to accommodate growth of the adult that occurs without molting.

Table 1.

DPY-7 localization in dpy mutants

| Gene | Lesion | DPY-7 in cuticle |

|---|---|---|

| dpy-2(e8) | Gly183Arg | None detected |

| dpy-2(sc38) | Gly129Glu | Fragmented |

| dpy-2(e1359) | ? | Fragmented |

| dpy-3(e27) | ? | Weak, fragmented |

| dpy-5(e61) | Gly202Stop | As wild type |

| dpy-7(e88) | Gly156Arg | Weak, fragmented |

| dpy-7(qm63) | deletion - null | None detected |

| dpy-8(e130) | ? | None detected |

| dpy-8(sc44) | ? | Fragmented |

| dpy-8(e1281) | ? | Fragmented |

| dpy-10(e128) | Splice site | None detected |

| dpy-10(sc48) | Gly137Glu | Fragmented |

| dpy-10(cn64) | Arg92Cys | None detected |

| dpy-13(e458) | ? | As wild type |

| dpy-13(e184) | 30-bp deletion | As wild type |

In all cases, strains were grown at 20°C. The nature of the lesion is given where known. The analyses of mutations in dpy-2 and dpy-10 (Levy et al., 1993), dpy-7 (Johnstone et al., 1992), and dpy-13 (von Mende et al., 1988) have been published, dpy-7(qm63) was analyzed by Jonathan Ewbank (personal communication) and confirmed in our laboratory; dpy-5(e61) was analyzed by Ann M. Rose (personal communication).

We observed one additional minor cuticle defect in dpy-5 and dpy-13 mutants. Whereas the annular furrows and DPY-7 stripes extend in a regular and uninterrupted manner nearly to the edge of the alae in wild-type (Figures 4, A and B, and 6A; our unpublished data), in the dpy-5 and dpy-13 mutants, there is a region adjacent to the alae where both of these structures show irregularities (Figures 5D and 6C).

With respect to all phenotypic characteristics discussed, we found dpy-5 and dpy-13 to be indistinguishable. We conclude that the DPY-5 and DPY-13 collagens are not required for formation of the DPY-7 bands or for the presence of the annular furrows on the surface of the cuticle. However, they are required for the normal width of the annuli.

Conversely, we found that the matrix localization of DPY-7 was drastically affected by mutant alleles of dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-8, or dpy-10 (Figure 6, D–H, and Table 1), and correspondingly, that the furrows delineating the annuli were either absent or severely altered in an allele-dependent manner (Figure 5, E–K). For each gene, we found at least one allele that caused a disruption similar to or more severe than that of the glycine substitution allele dpy-7(e88). In several cases, we found no detectible DPY-7 within the cuticle, as in the dpy-7(qm63) null. With dpy-8(e130), we also observed considerable intracellular accumulation of DPY-7 in some animals. In all cases, we found correlation between the appearance of DPY-7 in the cuticle and the surface of the cuticle. Where DPY-7 was found to be fragmented, the cuticle surface was dimpled; where no DPY-7 was detected in the cuticle, the cuticle surface was smooth. Not all of the mutant alleles have been sequenced, but among those that have are glycine substitution alleles in dpy-2 and dpy-10 (Table 1).

Thus, the presence and normal structure of DPY-2, DPY-3, DPY-8, and DPY-10 collagens are necessary for the assembly of the DPY-7 collagen into the mature matrix. We conclude that the five early expressed collagens are all required in a nonredundant manner for formation of the narrow band structures to which DPY-7 locates. These bands are necessary for the formation or persistence of the annular furrows to which they locate.

We also observed the localization of DPY-7 in mutants of three other collagen genes that have dissimilar loss-of-function phenotypes to that of dpy-7. rol-6 and sqt-1 are collagen genes for which loss of function probably results in a nearly wild-type appearance of the animals (Kramer and Johnson, 1993). (These genes were originally identified by gain-of-function alleles, intragenic suppressors of which identified loss-of-function alleles.) Conversely, sqt-3 is essential for animal viability, with loss-of-function alleles resulting in extreme Dpy phenotypes, the most severe causing lethality (van der Keyl et al., 1994). The dominant allele rol-6(su1006), which does not alter significantly the length of the animal, also does not affect the assembly of the DPY-7 containing bands (our unpublished data). The allele sqt-1(e1350) does cause a Dpy phenotype when homozygous; however, this is not a loss-of-function allele, and the phenotype probably results from the presence of aberrant collagen within the matrix. DPY-7 seems to be present in the matrix at approximately wild-type levels in this mutant background, but the bands that it forms are very disjointed and disorganized (Figure 6I). A similar and possibly more dramatic effect is seen for sqt-3(e2117). This allele is a glycine substitution mutant and is temperature sensitive, causing late embryonic lethality at the nonpermissive temperature. sqt-3(e2117) animals were allowed to progress through embryogenesis and early larval stages at the permissive temperature of 16°C and then were shifted to the nonpermissive 25°C and allowed to progress through one or two molts. This causes a severe Dpy phenotype in the resulting adults and extreme disruption to the continuity of the DPY-7 bands (Figure 6J). However, the fragmented bands are abundant within the mature matrix, and thus we conclude that SQT-3 is not required for the secretion of DPY-7 or its assembly into higher order structures, although it is required for the bands to adopt or maintain an intact morphology. The patterns of annular furrows as seen by scanning EM in the sqt-1(e1350) (Figure 5L) and sqt-3(e2117) (our unpublished data) mutant animals reflect the respective DPY-7 fragmented stripes in these mutants.

Localization of DPY-10 and DPY-13 Collagens in Wild-Type and Mutant Worms

From the data described above, it seems likely that the DPY-2, DPY-3, DPY-7, DPY-8, and DPY-10 collagens are all components of the same structure in the annular furrows. In contrast, DPY-5 and DPY-13 seemed likely to be components of a different matrix substructure that is required for the normal breadth of the annuli. To test these hypotheses, we constructed transgenes of dpy-7, dpy-10, and dpy-13 that contained Ty epitope tags (Bastin et al., 1996), the tag being positioned within the predicted mature amino-terminal non-Gly-X-Y domain of each encoded collagen. Each epitope-tagged transgene efficiently rescued the corresponding mutant strain (see MATERIALS AND METHODS), indicating that the tagged collagens function normally. We then tested the localizations of the epitope-tagged collagens in these phenotypically rescued animals by using an antibody reactive to the Ty tag. We found the localization of DPY-7::Ty detected with either the anti-Ty or anti-DPY-7 antibody to be indistinguishable from that of wild-type DPY-7 (our unpublished data). As hypothesized, we found that the DPY-10::Ty-tagged collagen was located in circumferential bands that correspond to the annular furrows (Figure 6K). In contrast, DPY-13::Ty localized to a distinct matrix structure (Figure 6N). Consistent with the reduced spacing of DPY-7 bands and annular furrows in dpy-13 mutants, DPY-13::Ty was found in broader and more diffuse bands that were positioned precisely between the DPY-7 bands, as indicated by double staining of the dpy-13::Ty transgenic animals with anti-Ty and anti-DPY-7 antibodies (Figure 6O). These DPY-13 bands were also located in a slightly deeper focal plane than DPY-7, so that the narrow DPY-7 stripes and broad DPY-13 stripes were not in focus at the same time.

Because mutation of dpy-10 affects the assembly of DPY-7, we tested whether mutation of dpy-7 also affects the assembly of DPY-10::Ty. In the dpy-7(e88) glycine-substitution mutant background, we found low levels of highly fragmented DPY-10::Ty in the cuticle (Figure 6L), indistinguishable in appearance from the localization of DPY-7(e88) collagen itself (Figure 6B). In the dpy-7(qm63) null background, we detected no DPY-10::Ty in the cuticle (Figure 6M). Thus, dpy-7 mutations have allele-dependent effects on the assembly of DPY-10::Ty similar to those seen for the assembly of DPY-7 in dpy-10 and other early dpy collagen gene mutant backgrounds. As expected from the effects of dpy-5 and dpy-13 mutations on the localization of DPY-7 (see above), depletion of DPY-5 by RNAi also caused DPY-10::Ty to assemble into stripes that coincided with the more closely spaced annular furrows (our unpublished data). We conclude that the assembly of the DPY-10 and DPY-7 collagens are interdependent.

The similarities between dpy-5 and dpy-13 (see above) suggested that the DPY-5 and DPY-13 collagens might be partners in the formation of the broad interfurrow bands. To test this hypothesis, we performed dpy-5 RNAi on a strain carrying the dpy-13::Ty-tagged transgene. Treated animals displayed a typical dpy-5 phenocopy, indicating that the RNAi was successful in reducing or removing DPY-5. We were unable to detect the DPY-13::Ty-tagged collagen in the cuticles of these animals (our unpublished data), whereas DPY-7 location showed the same alteration as seen in a dpy-5(e61) mutant strain. Thus, it is likely that the intermediate-expressed DPY-5 and DPY-13 collagens are obligate partners in the formation of a cuticle substructure that locates within each annulus and is essential for its normal breadth.

DPY-13::Ty Collagen Substructure Requires DPY-7 for Its Normal Pattern

We next tested the effect on DPY-13::Ty localization of reducing DPY-7 by RNAi. We found that DPY-13::Ty was assembled into the cuticle, indicating that DPY-13 does not require the presence of DPY-7 for its assembly into a macromolecular structure. However, the pattern of matrix substructure formed by DPY-13::Ty was dramatically altered when DPY-7 was reduced by RNAi: instead of the normal periodic striped pattern, DPY-13::Ty was assembled into a relatively amorphous layer within the cuticle (Figure 6P). We conclude that the DPY-7 stripes are necessary to define the gaps in the DPY-13 matrix substructure; in the absence of DPY-7, both the annular patterning of the surface of the cuticle and the striped pattern of the DPY-13 collagen matrix substructure are lost.

Early and Intermediate DPY Collagens Form Functionally Distinct Matrix Substructures

The data mentioned above suggest that the five early-expressed DPY collagens interact to form the narrow bands necessary for persistence of annular furrows and that the two intermediate-expressed DPY collagens interact to form the broader bands necessary for normal width of the annuli. If this is correct, we would predict that loss of any two collagens from within one group would result in a similar phenotype to loss of either collagen alone, whereas loss of one collagen from each group might have a compounded effect, because both substructures would be absent from the cuticle. As expected, we found that dpy-2(sc38);dpy-7(e88) and dpy-10(sc48);dpy-7(e88) double mutants have phenotypes similar to those of the single-mutant animals, whereas dpy-2(sc38);dpy-13(e458), dpy-10(sc48);dpy-13(e458), and dpy-13(e458);dpy-7(e88) double mutants all have a far more severe Dpy phenotype than do the single-mutant strains (Figure 2D). To extend this analysis, we used RNAi to reduce or remove individual collagens in wild-type and various mutant backgrounds (Table 2). dpy-7, dpy-10, or dpy-5 RNAi performed on wild-type animals phenocopied efficiently the strong mutant phenotypes of the respective genes. As expected, in mutants defective in an early-expressed gene (dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-7, dpy-8, or dpy-10), RNAi of an early gene (dpy-7 or dpy-10) did not affect the severity of the phenotype, whereas in a mutant of an intermediate-expressed gene (dpy-5 or dpy-13), it caused a severe Dpy phenocopy, indistinguishable from those of the double mutants discussed above.

Table 2.

Effects of loss of two collagen species by mutation plus RNAi

| Strain | Phenotype after RNAi depletion of

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| DPY-7 | DPY-10 | DPY-5 | |

| N2 (wild type) | Dpy | Dpy | Dpy |

| dpy-2(e8) | No change | No change | Severe Dpy |

| dpy-3(e27) | No change | No change | Severe Dpy |

| dpy-7(qm63) | No change | No change | Severe Dpy |

| dpy-8(e130) | No change | No change | Severe Dpy |

| dpy-10(e128) | No change | No change | Severe Dpy |

| dpy-5(e61) | Severe Dpy | Severe Dpy | No change |

| dpy-13(e458) | Severe Dpy | Severe Dpy | No change |

Strains were grown on RNAi plates for dpy-7, dpy-10, or dpy-5. RNAi for these genes performed on the wild-type strain N2 caused Dpy effects similar to the phenotypes of the respective strong loss-of-function alleles. In all cases where an effect could be seen, the RNAi phenocopy affected >95% of the animals grown through their complete life cycle on the RNAi plates. No change, the phenotype of the mutant was not altered by the RNAi; severe Dpy, exacerbated phenotype similar to that of the dpy-13;dpy-7 double mutant.

Conversely, RNAi of the intermediate gene dpy-5 had no effect on the phenotype of either dpy-5 or dpy-13 mutants but caused a severe Dpy phenocopy in all of the five early-gene mutants tested. We therefore conclude that the early- and intermediate-expressed cuticle collagens discussed here form two functionally distinct substructures that cooperate to produce the normal cuticle.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated two distinct functions for a group of C. elegans cuticle collagens that are characterized by loss-of-function alleles that result in the Dpy short, fat body phenotype. By scanning electron microscopy, we found that these dpy mutants fall into two distinct classes: dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-7, dpy-8, and dpy-10, which have no cuticular annuli; and dpy-5 and dpy-13, which have narrow annuli. These two groups of collagen genes are expressed at different times during each cuticle synthetic period, ∼ 4 and ∼2 h before cuticle secretion, respectively. Consistent with the no annuli phenotype of the dpy-2 group of mutants, the DPY-7 and DPY-10 collagens are assembled into narrow band-like substructures in the furrows that delineate the annuli. Mutations in dpy-2, dpy-3, dpy-8, or dpy-10 prevent the assembly of the DPY-7 bands, and dpy-7 mutations prevent the assembly of DPY-10. We suggest that the most likely explanation of these observations is that DPY-2, DPY-3, DPY-7, DPY-8, and DPY-10 are all obligate partners in the formation of the collagenous bands that are essential for annular furrow formation or maintenance.

The reciprocal effects of different mutant alleles seem particularly significant. For example, the null allele dpy-7(qm63) causes an absence of DPY-10::Ty collagen from the matrix, and the strong loss-of-function allele dpy-10(e128) causes an absence of DPY-7. In contrast, the glycine substitution allele dpy-7(e88), which results in small amounts of highly fragmented DPY-7(e88) collagen being located in the cuticle, also causes small amounts of highly fragmented DPY-10::Ty to be assembled into the cuticle. These observations strongly support an interaction between these two collagens. Other mutant alleles, including other glycine substitution mutants, of the early-expressed dpy collagen genes produce a similar spectrum of effects on the assembly of DPY-7, and the amounts of DPY-7 incorporated into the cuticle in these mutants are correlated with the severity of the Dpy phenotypes. Glycine substitution mutations in vertebrate collagens are associated with a variety of heritable diseases, including osteogenesis imperfecta (Prockop and Kivirikko, 1995; Forlino and Marini, 2000). Glycine substitutions within the repetitive Gly-X-Y domains of collagen can result in a regional destabilization of the collagen triple helical structure (Olague-Marchan et al., 2000); the structure requires glycine at each third residue of each participating monomeric chain (Engel and Prockop, 1991). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the interactions among the early collagens are at the level of trimer formation. However, as we have identified four different collagens that affect similarly the assembly of DPY-7, this could only be the case if DPY-7 formed heterotrimers with all four other interacting collagens, and each of these trimer species were necessary for the assembly of the band-like structures. Alternatively, the interactions could be higher order, with individual early-expressed collagens forming homotrimers. Clearly, a combination of these two scenarios is also possible.

Consistent with the presence of annuli and the furrows that delineate them, the DPY-7–containing circumferential bands are present in dpy-5 and dpy-13 mutants. However, the annuli do not have normal breadth. Consistent with this, DPY-13::Ty was detected in diffuse bands that localize between the DPY-7–containing bands within each annulus. As with the early-expressed DPY collagens, the intermediate-expressed collagens DPY-5 and DPY-13 seem to interact, because reduction or removal of DPY-5 by RNAi causes loss of DPY-13::Ty from the cuticle. In contrast, reduction or removal of DPY-7 by RNAi does not prevent the assembly of DPY-13::Ty into the cuticle, but it does cause the DPY-13–containing matrix substructure to adopt an amorphous appearance, as opposed to the normal broad striped pattern. Thus, the early-expressed collagens play a critical role in patterning of the cuticle, being required both for the normal annular patterning visible on the surface and for the normal striped pattern of the matrix substructure.

Our model that the five early-expressed and two intermediate-expressed DPY collagens form two functionally distinct but cooperating cuticle substructures is supported by the combined double mutant and RNAi analysis. Removal of one collagen from each group results in a much more severe Dpy phenotype than does loss of any single collagen. In contrast, loss of two collagens from the same group results in no more severe phenotype than does loss of a single collagen.

We have shown previously that the cuticle collagen genes are expressed in the same temporal sequence during each cuticle synthetic phase (Johnstone and Barry, 1996), and we hypothesized that this sequential expression may exist to facilitate partner finding and the formation of correct interactions among the encoded collagens of this large gene family. This hypothesis is consistent with the data presented herein for the early-expressed DPY cuticle collagens. Because the mRNAs of these genes are all abundant 4 h before cuticle secretion, it is reasonable to assume that the encoded collagens are synthesized within the ER at the same time. We have shown this to be true in the embryo for DPY-7 and DPY-10, because these collagens are detected by immunofluorescence in a perinuclear location from the comma stage of embryogenesis. Similarly, the intermediate-expressed collagens would presumably be synthesized only when their mRNAs are abundant, 2 h before cuticle secretion. Thus, the components of different cuticle substructures could be at least partly preassembled before secretion; by synthesizing different sets of collagens at different times during the 4-h period before secretion, the synthetic hypodermal cells would act like an assembly line, making different substructures at different times.

Finally, as the position of the furrows in the outer layer of the cuticle seems to be determined by the furrows that form transiently on the surface of the hypodermal membrane during cuticle secretion, which in turn are generated by the transient circumferential actin filaments that form within the hypodermal cells (Costa et al., 1997), it follows that the position of the early-expressed collagen bands is determined, either directly or indirectly, by the positions of these actin filaments. Furrowing of the membrane above the actin bundles suggests a physical attachment between the cell membrane and the actin bundles, necessary to provide the force to alter the shape of the membrane. Assuming that such a physical attachment exists, it may provide a mechanism to regulate the positioning of the collagen bands on the outer surface of the hypodermal membrane. The existence of an active molecular mechanism for positioning these bands is also supported by their absence from the surface of seam cells at stages when alae are present, the L1 larva and the adult. We have shown that during synthesis of the L1 larval cuticle, DPY-7 protein is detected within seam cells before secretion. Thus, there must be a biochemical difference between the membrane surface of the seam cells, where DPY-7 is absent, and the surface of the dorsal and ventral hypodermis, where DPY-7 is present. The transient actin bundles are also found in the dorsal and ventral hypodermis, but not the seam cells, consistent with a putative role in positioning the DPY-7 collagen bands. Investigation of the mechanism of polymerization and localization of the DPY cuticle collagens into ECM substructures that are patterned by components of the cytoskeleton may identify general aspects of interaction between cytoskeleton and ECM that are common to all animals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

L.M., J.M.M., B.R. contributed approximately equally to the work and these authors are named in alphabetic order. We acknowledge Laurence Tetley for assistance with electron microscopy, Keith Gull for the gift of the anti-Ty monoclonal cell line, Michel Labouesse for anti-LIN-26 antibody, and Robert Waterston for the MH27 antibody. The C. elegans Genome Sequencing Consortium is acknowledged for provision of essential data and in particular Alan Coulson for provision of cosmids essential for cloning dpy-3 and dpy-8. I.L.J. is a Medical Research Council Senior Fellow in Biomedical Sciences and L.M. was the recipient of a Wellcome Trust Prize Studentship. The research was also in part funded by a grant from The Leverhulme trust.

Footnotes

Online version of this article contains supplementary data. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–08–0479. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–08–0479.

REFERENCES

- Bastin P, Bagherzadeh A, Matthews KR, Gull K. A novel epitope tag system to study protein targeting and organelle biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;77:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Draper BW, Priess JR. The role of actin filaments in patterning the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle. Dev Biol. 1997;184:373–384. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GN, Kusch M, Edgar RS. Cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans: its isolation and partial characterization. J Cell Biol. 1981a;90:7–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GN, Strapans S, Edgar RS. The cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans. II. Stage-specific changes in ultrastructure and protein composition during postembryonic development. Dev Biol. 1981b;86:456–470. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J, Prockop DJ. The zipper-like folding of collagen triple helices and the effects of mutations that disrupt the zipper. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1991;20:137–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlino A, Marini JC. Osteogenesis imperfecta: prospects for molecular therapeutics. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71:225–232. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R, Waterston RH. Muscle cell attachment in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:465–479. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard JS, Barry JD, Johnstone IL. cis regulatory requirements for hypodermal cell-specific expression of the Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle collagen gene. dpy-7. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2301–2311. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone IL. The cuticle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: a complex collagen structure. Bioessays. 1994;16:171–178. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone IL. Cuticle collagen genes - expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 2000;16:21–27. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01857-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone IL, Barry JD. Temporal reiteration of a precise gene-expression pattern during nematode development. EMBO J. 1996;15:3633–3639. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone IL, Shafi Y, Barry JD. Molecular analysis of mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans collagen gene. dpy-7. EMBO J. 1992;11:3857–3863. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM. Genetic analysis of extracellular matrix in C. elegans. Annu Rev Genet. 1994;28:95–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.28.120194.000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM. Extracellular Matrix. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 471–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM, Johnson JJ. Analysis of mutations in the sqt-1 and rol-6 collagen genes of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;135:1035–1045. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.4.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JM, Johnson JJ, Edgar RS, Basch C, Roberts S. The sqt-1 gene of C. elegans encodes a collagen critical for organismal morphogenesis. Cell. 1988;55:555–565. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouesse M, Sookhareea S, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-26 is required to specify the fates of hypodermal cells and encodes a presumptive zinc-finger transcription factor. Development. 1994;120:2359–2368. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy AD, Yang J, Kramer JM. Molecular and genetic analyses of the Caenorhabditis elegans dpy-2 and dpy-10 collagen genes - a variety of molecular alterations affect organismal morphology. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:803–817. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.8.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DM, Shakes DC. Immunofluorescence microscopy. In: Epstein HF, Shakes DC, editors. Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern Biological Analysis of an Organism. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 365–394. [Google Scholar]

- Olague-Marchan M, Twining SS, Hacker MK, McGrath JA, Diaz LA, Giudice GJ. A disease-associated glycine substitution in BP180 (type XVII collagen) leads to a local destabilization of the major collagen triple helix. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto CA, Desouza W. Freeze-fracture and deep-etched view of the cuticle of Caenorhabditis elegans. Tissue Cell. 1995;27:561–568. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(05)80065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto CA, Kramer JM, Desouza W. Caenorhabditis elegans cuticle: a description of new elements of the fibrous layer. J Parasitol. 1997;83:368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI. Collagens - molecular-biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:403–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RN, Sulston JE. Some observations on moulting in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nematologica. 1978;24:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, editor. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Court D, Fire A. Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 2001;263:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Keyl H, Kim H, Espey R, Oke CV, Edwards MK. Caenorhabditis elegans sqt-3 mutants have mutations in the col-1 collagen gene. Dev Dyn. 1994;201:86–94. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002010109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mende N, Bird DM, Albert PS, Riddle DL. dpy-13: a nematode collagen gene that affects body shape. Cell. 1988;55:567–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.