Abstract

Aurora-B is a protein kinase required for chromosome segregation and the progression of cytokinesis during the cell cycle. We report here that Aurora-B phosphorylates GFAP and desmin in vitro, and this phosphorylation leads to a reduction in filament forming ability. The sites phosphorylated by Aurora-B; Thr-7/Ser-13/Ser-38 of GFAP, and Thr-16 of desmin are common with those related to Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase), which has been reported to phosphorylate GFAP and desmin at cleavage furrow during cytokinesis. We identified Ser-59 of desmin to be a specific site phosphorylated by Aurora-B in vitro. Use of an antibody that specifically recognized desmin phosphorylated at Ser-59 led to the finding that the site is also phosphorylated specifically at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis in Saos-2 cells. Desmin mutants, in which in vitro phosphorylation sites by Aurora-B and/or Rho-kinase are changed to Ala or Gly, cause dramatic defects in filament separation between daughter cells in cytokinesis. The results presented here suggest the possibility that Aurora-B may regulate cleavage furrow-specific phosphorylation and segregation of type III IFs coordinatedly with Rho-kinase during cytokinesis.

INTRODUCTION

Intermediate filaments (IFs) constitute major components of the cytoskeleton and the nuclear envelope in most cell types (for review see Eriksson et al., 1992; Fuchs and Weber, 1994). Unlike other cytoskeletons such as microtubules and actin filaments, the protein components of IFs vary in a cell-, tissue-, and differentiation-dependent manner and include at least six groups (type I–type VI; for review see Fuchs and Weber, 1994; Klymkowsky, 1995; Steinert and Roop, 1988). Although IFs were thought to be relatively stable compared with actin filaments and microtubules, intensive in vitro investigations revealed that site-specific phosphorylation by several kinases, such as protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), Ca2+/Calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII), cdc2 kinase, and Rho-kinase alters dynamically their structure and induces filament disruption (for review see Inagaki et al., 1996). Thereafter, some of the above kinases were found to be in vivo IF kinases, as determined using site- and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies that recognize a phosphorylated Ser/Thr residue and its flanking sequence.

During cytokinesis, the cleavage furrow forms between daughter nuclei, after which the essential cell components are segregated into postmitotic daughter cells. Protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is thought to play pivotal roles in mitotic processes, including cytokinesis (Hunt, 1991; Norbury and Nurse, 1992; Nigg, 1993). We earlier identified Rho-kinase to be a protein kinase playing an essential role on IFs organization at the cleavage furrow during the mitotic process (Yasui et al., 1998; Kosako et al., 1999). We also identified a novel kinase for IF proteins at cleavage furrow areas in the late mitotic phase, such being important for efficient IFs separation between daughter cells in cell division (Yasui et al., 2001).

Aurora/Ipl1p-related proteins, a family of serine/threonine kinases conserved from the budding yeast to mammals are involved in various stages of mitosis (Giet and Prigent, 1999; Bischoff and Plowman, 1999; Adams et al., 2001a; Nigg, 2001). Although the yeast genome encodes only one kinase, mammals have at least three members of the Aurora/Ipl1p-related kinase subfamily (Bischoff and Plowman, 1999; Adams et al., 2001a; Nigg, 2001). Among these, Aurora-A functions in centrosome separation and spindle bipolarity (Glover et al., 1995; Roghi et al., 1998; Giet and Prigent, 2000), whereas Aurora-B appears to function in both early and late mitotic events; chromosome segregation and cytokinesis (Bischoff et al., 1998; Schumacher et al., 1998; Terada et al., 1998). Immunocytochemistry studies demonstrated that Aurora-B localizes at chromosomal centromeres from prophase to metaphase and subsequently relocates to the spindle midzone (Schumacher et al., 1998; Adams et al., 2001b; Giet and Glover, 2001) and to the equatorial cortex (Murata-Hori et al., 2002) during anaphase and telophase. Changes in the localization of Aurora-B may serve as effective mechanisms for defining its substrates in a spatiotemporal manner. Recently, Aurora-B was reported to phosphorylate histone H3 during the earlier mitotic phase (Hsu et al., 2000; Adams et al., 2001b; Giet and Glover, 2001; Murnion et al., 2001; Goto et al., 2002). This phosphorylation is thought to be required for correct chromosome segregation (Wei et al., 1999; Hsu et al., 2000; Adams et al., 2001b; Giet and Glover, 2001). On the other hand, two targets of Aurora-B in cytokinetic processes, INCENP and ZEN-4/CeMKLP1, have been reported in Caenorhabditis elegans (Kaitna et al., 2000; Severson et al., 2000; Mishima et al., 2002).

Because identification the substrate(s) of Aurora-B in the late mitotic phase is essential to elucidate physiological functions of the kinase in the cell cycle, much effort has been made to identify these substrates. Recently, we found that vimentin may be a possible substrate for Aurora-B (unpublished data). In the present study, our data suggest the possibility that Aurora-B phosphorylates desmin and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant human GFAP and desmin were prepared from Escherichia coli, as described (Inagaki et al., 1988; Sekimata et al., 1996). Aurora-B(K/R) was prepared using QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, CA). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Aurora-B and GST-Aurora-B(K/R) were purified from E. coli, as described (Goto et al., 2002). GFAP and desmin phosphorylated by the catalytic subunit of A-kinase, Rho-kinase, or Aurora-B were prepared, as described (Kosako et al., 1997; Inada et al., 1998) or as below.

Plasmid Construction

For expression of GFAP or desmin, cDNA for human GFAP (Reeves et al., 1989) or desmin (Inada et al., 1998) was introduced in the expression vector pDR2 (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). For site-directed mutagenesis, we used PCR with oligonucleotide mutation primers and the template GFAP or desmin cDNA.

Phosphorylation of GFAP and Desmin

The phosphorylation reaction for Aurora-B was done for the indicated times at 25°C in 100 μl of 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 2 mM MgCl2, 100 μM [γ-32P]ATP, 0.1 μM calyculin A, 100 μg/ml GFAP or desmin, and 10 μg/ml purified Aurora-B kinase. Reaction mixtures were boiled in Laemmli's sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Filament Assembly and Microscopy

GFAP and desmin were phosphorylated in the presence of GST-Aurora-B or GST-Aurora-B(K/R) for 1 h at 25°C. For polymerization of samples, the phosphorylated GFAP was dialyzed in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl at 25°C overnight, and the phosphorylated desmin was incubated with 100 mM NaCl for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were subjected to high-speed centrifugation (12,000 × g) for 1 h at 4°C and supernatants and precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE. After the polymerization reaction, each sample was placed directly on carbon film-coated specimen grids and stained with 2% uranyl acetate for electron microscopic examinations.

Fragmentation of Phosphorylated GFAP and Desmin

GFAP or desmin (100 μg) was phosphorylated by GST-Aurora-B kinase (10 μg) at 25°C for 2 h to a stoichiometry of 1.0 or 1.5 mol of phosphate/mol of protein, respectively, in 1 ml of the reaction mixture with [γ-32P] ATP as described above. The radioactive IFs were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, dissolved in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) containing 4 M urea, and then digested with 5 μg of lysyl-endopeptidase (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) for 4 h at 30°C. The digested samples were fractionated by reverse-phase HPLC on a Zorbax C8 column (0.46 × 25 cm) equilibrated with 5% (vol/vol) 2-propanol/acetonitrile (7:3) containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The peptides were eluted with a 60-min linear gradient of 5–50% (vol/vol) 2-propanol/acetonitrile, followed by a further 10-min linear gradient of 50–80% (vol/vol) 2-propanol/acetonitrile. All radioactivity of digested GFAP or desmin recovered in a single peak with the retention time of 61–64 or 59–62 min, respectively. This phosphorylated peptide was vacuum-dried, resuspended in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), and treated with 1/50 (wt/wt) l-1-tosylamide-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin (Sigma) at 37°C for 8 h. The samples were treated again for an additional 8 h using the same methods. The obtained peptides were fractionated by HPLC on the Zorbax C8 column, as described. All chromatography was done at room temperature at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min and a fraction size of 0.8 ml.

Amino Acid Sequence Analysis and Phosphoamino Acid Analysis of Tryptic Peptides

Amino acid sequences of each phosphopeptide were analyzed using an ABI 476A gas-phase sequencer. To determine at which position on GFAP or desmin each peptide exists, the sequences were then compared with the amino acid sequence predicted from human GFAP or desmin cDNA. Phosphoserine-containing peptides were treated with ethanethiol at alkaline pH, as described (Meyer et al., 1986). The ethanethiol-modified peptides were then sequenced as above.

Peptide Synthesis and Production of Anti-PD11, Anti-PD59 Antibodies

Desmin peptides, PD11 (phosphodesmin–Ser-11; Cys-Ser-Ser-Gln-Arg-Val-phospho-Ser11-Ser-Tyr-Arg-Arg-Thr), D11 (Cys-Ser-Ser-Gln-Arg-Val-Ser-Ser-Tyr-Arg-Arg-Thr), PD59 (phosphodesmin–Ser-59; Cys-Gln-Val-Ser-Arg-Thr-phospho-Ser59-Gly-Gly-Ala-Gly-Gly), D59 (Cys-Gln-Val-Ser-Arg-Thr-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ala-Gly-Gly) were chemically synthesized, at Peptide Institute Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Antibodies against PD11 and PD59 were prepared as described (Nishizawa et al., 1991; Goto et al., 1998). Characterization of the antibodies was done as described elsewhere (Goto et al., 1998; Inada et al., 1999). Western blotting was done as described (Nishizawa et al., 1991), using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies and the ECL Western blotting detection system (Amersham Corp.).

Cell Culture

Human osteosarcoma Saos-2 cells (a gift from Dr. H. Saya, Kumamoto University, Japan), COS-7, EBNA-expressing T24 (Yasui et al., 1998), and Swiss3T3 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, and streptomycin in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Transfection and Immunocytochemistry

COS-7 and T24 cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates, and the next day were transfected using Lipofectamine Plus (GIBCO BRL). Twenty-four or 48 h after transfection, the cells were fixed for immunocytochemical studies. Cells growing on glass coverslips were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in ice-cold PBS for 10 min and then treated with methanol at −20°C for 10 min. Incubation with primary antibodies in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum was for 2 h at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h with appropriate secondary antibodies and subsequently washed with PBS. Then DNAs were stained with 0.5 mg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma). In some experiments, mitotic cells were prepared as follows. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with 15 ng/ml 3-(1-anilinoethylidene)-5-benzylpyrrolidine-2,4-dione (TN-16; Wako Chemical, Neuss, Germany) for 4 h and mitotic cells were collected. After washing with DMEM to remove TN-16, cells were plated on glass coverslips and then incubated for 3 h at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% FBS to allow for cell cycle progression. IF-bridge formation was analyzed immunocytochemically. Fluorescently labeled cells were examined using either an Olympus BH2-RFCA microscope or an Olympus LSM-GB200 confocal microscope.

RESULTS

In Vitro Phosphorylation of GFAP and Desmin by Aurora-B

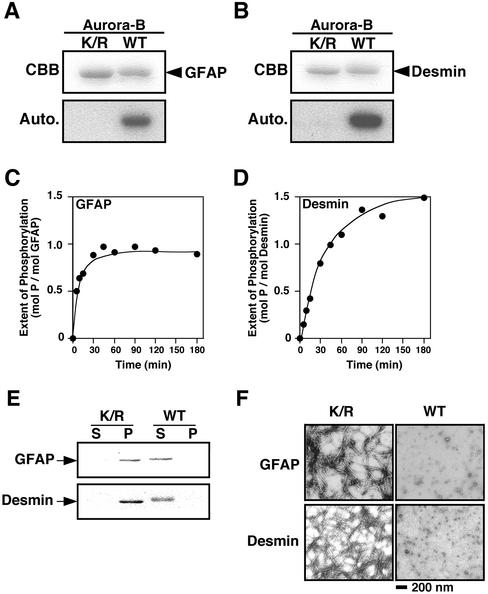

We reported that vimentin is phosphorylated at Ser-72 by an unidentified kinase activity at the cleavage furrow in the late mitotic phase (Yasui et al., 2001). Because Aurora-B is localized at the spindle midzone and the equatorial cortex, it was considered to be a candidate for the novel protein kinase. We therefore determined if Aurora-B phosphorylates type III intermediate filament (IF) proteins, including GFAP and desmin, in vitro. As shown in Figure 1, A and B, these filament proteins were indeed phosphorylated by Aurora-B, but not by Aurora-B(K/R), which is a kinase-negative version with a mutation at the ATP-binding site. The phosphorylation level of GFAP increased in a time-dependent manner up to 1.0 mol of phosphate/mol of protein (Figure 1C), whereas the level of desmin reached 1.5 mol of phosphate/mol of protein (Figure 1D). We then examined effects of the phosphorylation on the filament forming potential of GFAP and desmin. Soluble GFAP or desmin was preincubated with Aurora-B or the K/R mutant for 1 h, and the samples were incubated under conditions of polymerization. Analyses of these samples by centrifugation (Figure 1 E) and by electron microscopy (Figure 1F) revealed that the phosphorylation of GFAP or desmin by Aurora-B dramatically inhibited filament formation. Thus, phosphorylation of GFAP and desmin by Aurora-B affects the state of polymerization of filaments in vitro.

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of GFAP and desmin by Aurora-B and the effect of phosphorylation on filament formation. GFAP (A) and desmin (B) were treated with Aurora-B (WT) or Aurora-B (K/R) and analyzed using SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. (C and D) Time course study of phosphorylation of GFAP (C) and desmin (D) by Aurora-B. (E) After the polymerization reaction of phosphorylated/unphosphorylated GFAP and phosphorylated/unphosphorylated desmin and centrifugation, supernatants (S), and precipitates (P) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. (F) After incubation, the samples were subjected to the electron microscopy. Note that Aurora-B phosphorylated GFAP and desmin, and the phosphorylation inhibited their filament forming ability, in vitro. Bar, 200 nm.

Identification of In Vitro Phosphorylation Sites on GFAP and Desmin by Aurora-B

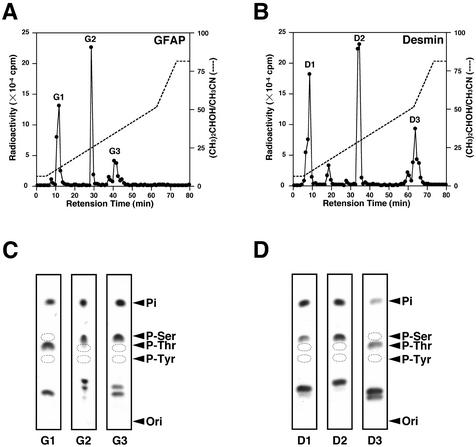

To identify the sites on GFAP phosphorylated by Aurora-B, GFAP was first exposed to Aurora-B in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Phosphorylated GFAP was treated with lysyl-endopeptidase and subjected to reverse-phase HPLC, and the resultant peptide was digested with trypsin and again applied to a reverse-phase HPLC column. As shown in Figure 2A, three major radioactive peptides, G1 to G3, were obtained, the G1 peptide was phosphorylated at a threonine residue, and G2 and G3 peptides were phosphorylated at serine residues, as determined by phosphoamino acid analysis (Figure 2C). The phosphoserine-containing peptides were then sequenced after ethanethiol treatment which specifically converts phosphoserine into S-ethylcysteine. The generation of S-ethylcysteine at a particular Edman degradation cycle where serine is predicted provides a definitive way to locate the phosphoserine residue(s) on each peptide. The lack of generation of S-ethylcysteine indicates that phosphoserine is located in the amino-terminal serine residue as there is no conversion of the amino-terminal phosphoserine to S-ethylcysteine. Indeed, phosphates of G1, G2, and G3 peptides were found to be located on Thr-7, Ser-38, and Ser-13 on GFAP, respectively (Table 1). We also examined the sites phosphorylated by Aurora-B on desmin using the same methods described above. A peptide derived from phosphorylated desmin digested with lysyl-endopeptidase was treated with trypsin and subjected to reverse-phase HPLC. The three major radioactive peptides, D1 to D3, were obtained (Figure 2B), and D1 and D2 peptides were phosphorylated at serine residues, whereas the D3 peptide was phosphorylated at a threonine residue, as determined by phosphoamino acid analysis (Figure 2D). Phosphates of D1, D2, and D3 peptides were found to be located on Ser-11, Ser-59, and Thr-16, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Analysis of trypsin-digested fragments of phosphorylated GFAP and desmin. (A and B) The radioactive single peptide of GFAP (A) and desmin (B) was digested with trypsin and fractionated by reverse-phase HPLC. The radioactivity of each fraction was measured in 32P Beckman liquid scintillation counter. (C and D) Phosphopeptides indicated above were subjected to phosphoamino acid analysis. The positions of phosphoserine (P-Ser), phosphothreonine (P-Thr), and phosphothreonine (P-Tyr) are indicated. Ori, origin.

Table 1.

Amino acid sequence of 32P-labeled phosphopeptides of GFAP and desmin by Aurora-B

| Phosphopeptide | Amino acid sequence | Phosphorylation site |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | RITSAARR | Thr-7 |

| G2 | LSLAR | Ser-38 |

| G3 | SYVSSGEMMVGGLAPGR | Ser-13 |

| D1 | VSSYR | Ser-11 |

| D2 | TSGGAGGLGSLR | Ser-59 |

| D3 | TFGGAPGFPLGSPLSSPVFPR | Thr-16 |

Phosphorylation sites are underlined.

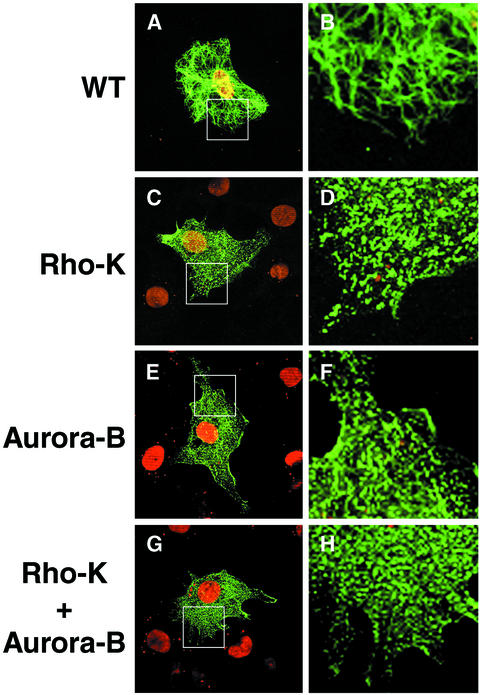

Effects of Mutation of Desmin at Aurora-B and Rho-kinase Phosphorylation Sites on Filament Formation

To examine effects of phosphorylation on the filament organization of desmin, we constructed a set of desmin mutants in which in vitro phosphorylation sites by Aurora-B (Ser-11, Thr-16, and Ser-59), Rho-kinase (Thr-16, Thr-75, and Thr-76), or both were changed to Asp. These mutants are assumed to mimic desmin phosphorylated by Aurora-B, Rho-kinase, or both. When wild-type desmin or these mutants were transiently expressed in T24 cells that do not express any type III IFs, wild-type desmin showed a filamentous pattern (Figure 3, A and B). Desmin with mutations in Rho-kinase or Aurora-B phosphorylation sites was no longer filamentous rather was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm (Figure 3, C–F). Desmin with mutations in Rho-kinase and Aurora-B phosphorylation sites showed a markedly diffuse localization (Figure 3, G and H). These findings suggest that the in vitro desmin phosphorylation at sites of Aurora-B and/or Rho-kinase induce disassembly of the filaments in vivo. The same phenotype was observed when a GFAP mutant in which in vitro Aurora-B phosphorylation sites were changed to Asp was expressed in cells (unpublished data). It is notable that 100% of the cells expressing the desmin or GFAP mutants showed diffuse localization of the expressed IFs.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence staining of T24 cells expressing desmin and the mutants. T24 cells were transfected with pDR2-desmin (A and B) or pDR2-mutated desmin in which phosphorylation sites by Rho-kinase (C and D), Aurora-B (E and F), or both (G and H) are changed to Asp. The green color represents desmin immunoreactivity by α-desmin (Dako). DNA was stained by propidium iodide (red). The regions in white boxes in A, C, E, and G are shown magnified (B, D, F, and H). Data presented here suggest that the desmin phosphorylation at the sites of Aurora-B and/or Rho-kinase leads to reduction of their filament forming ability in cells. Bar, 20 μm.

Comparison of In Vitro Phosphorylation Sites by Aurora-B to Rho-kinase and Production of the Site- and Phosphorylation State-specific Antibodies for Desmin

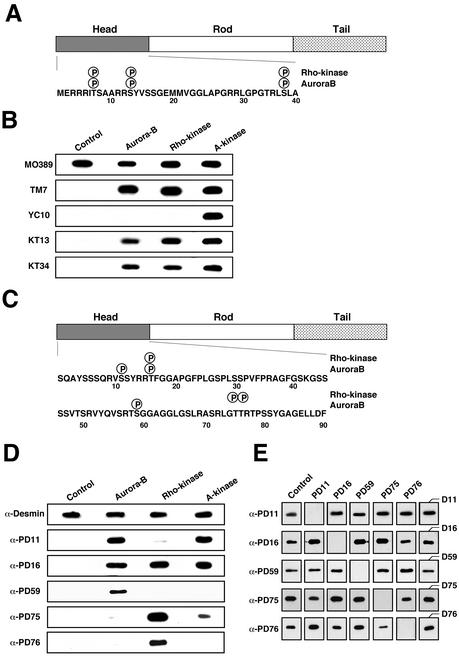

In a previous study, we found that Rho-kinase phosphorylates GFAP at Thr-7, Ser-13, and Ser-38 in vitro (Figure 4A; Kosako et al., 1997), and the phosphorylation is observed at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis in vivo (Nishizawa et al., 1991; Matsuoka et al., 1992; Kosako et al., 1997; Yasui et al., 1998). In the present study we found the same phosphorylation sites to be those for Aurora-B in vitro (Table 1). When we made a Western blot analysis with TMG7, YC10, KT13, or KT34, which reacts with GFAP phosphorylated at Thr-7, Ser-8, Ser-13, or Ser-38, respectively (Nishizawa et al., 1991; Matsuoka et al., 1992; Kosako et al., 1997; Yasui et al., 1998), we confirmed that Aurora-B phosphorylates GFAP at Thr-7, Ser-13, and Ser-38 but not at Ser-8, whereas PKA phosphorylated all four residues (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation site maps of GFAP and desmin by Aurora-B and Rho-kinase and characterization of antibodies by Western blotting. (A and C) Location of the sites on GFAP (A) and desmin (C) phosphorylated by Aurora-B and Rho-kinase is shown. The phosphorylation sites are indicated by P within a circle. (B) GFAP unphosphorylated (control) or phosphorylated by Aurora-B, Rho-kinase, or A-kinase was separated by SDS-PAGE (100 ng in each lane) followed by Western blotting. The membrane was probed using antibodies TMG7, YC10, KT13, and KT34. TMG7, YC10, KT13, and KT34 react with GFAP phosphorylated at Thr-7, Ser-8, Ser-13, and Ser-38, respectively. MO389 reacts with both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated GFAPs. (D) Unphosphorylated desmin (control) or phosphorylated desmin was analyzed using α-PD11, α-PD16, α-PD59, α-PD75, and α-PD76, which react with desmin phosphorylated at Ser-11, Thr-16, Ser-59, Thr-75, and Thr-76, respectively, and with antidesmin antibody (α-Desmin). (E) Specificity of the antiphosphodesmin antibodies, using an immunoabsorption assay. Desmin (100 ng) phosphorylated by Rho-kinase or Aurora-B was immunoblotted with the antiphosphodesmin antibodies after absorption with each synthetic phospho-peptide (50 μg/ml) used as an antigen (PD11, PD16, PD59, PD75, and PD76) or respective nonphosphorylated peptides (last column). The phosphorylated desmin was immunoblotted with each antiphosphodesmin without preabsorption (control). Antiphospho-GFAP and antiphosphodesmin antibodies used in the experiments recognized corresponding site-specific phosphorylation in vitro.

Rho-kinase was found to phosphorylate desmin at Thr-16, Thr-75, and Thr-76 (Figure 4C; Inada et al., 1999). In the present study, we found Aurora-B phosphorylates desmin at Ser-11, Thr-16, and Ser-59, in vitro. Because Ser-59 of desmin is a phosphorylation site specific to Aurora-B in vitro, the residue might serve as a pertinent indicator to study in vivo desmin phosphorylation by Aurora-B. We next prepared rabbit polyclonal antibodies (referred to as α-PD11 and α-PD59), raised against the synthetic phosphopeptides, PD11 and PD59. In Figure 4, D and E, the specificity of α-PD11 and α-PD59 was examined and compared with that of other antiphosphodesmin antibodies such as α-PD16, α-PD75, or α-PD76, using Western blotting. Although α-PD59 specifically reacted with desmin phosphorylated by Aurora-B, but not that by Rho-kinase and PKA, Ser-11 as well as Thr-16 and Thr-75 of desmin was phosphorylated by PKA in vitro (Figure 4D). As shown in Figure 4E, the immunoreactivity of α-PD11 and α-PD59 for desmin phosphorylated by Aurora-B was neutralized by preincubation with PD11 and PD59, respectively, but not with phosphopeptides PD16, PD75, and PD76; thus, the specificity of the two antibodies was confirmed.

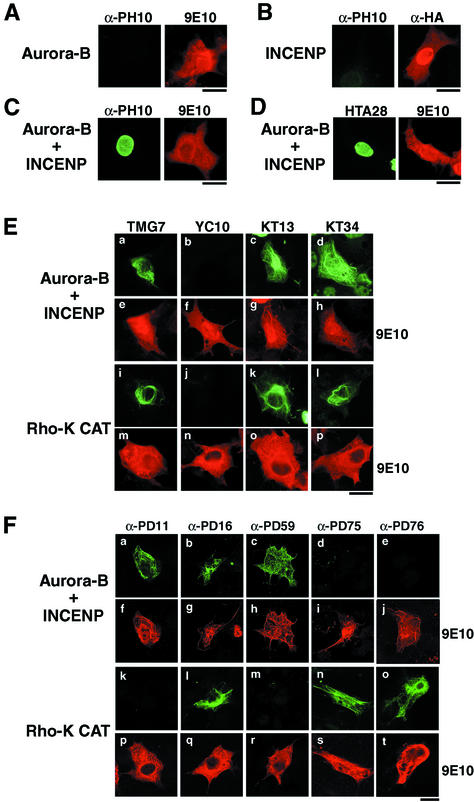

Phosphorylation of Desmin at Ser-11 and Ser-59 by Ectopic Expression of Active Aurora-B in COS-7 Cells

The inner centromere protein (INCENP) was reported to interact with Aurora-B and be phosphorylated by the kinase, after which Aurora-B kinase activity was increased, in vitro (Kaitna et al., 2000; Bishop and Schumacher, 2002). On the other hand, RNA interference (RNAi) study using Drosophila S2 cells revealed that INCENP is essential for Aurora-B–mediated phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 (Adams et al., 2001b). In the present study, we observed the phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser-10 in interphase when Aurora-B is coexpressed with INCENP in COS-7 cells (Figure 5, A–C). The findings demonstrated that Aurora-B is activated through interactions with INCENP in vivo as well as in vitro. Under these conditions, activated Aurora-B also induced phosphorylation at Ser-28 of histone H3 in interphase cells (Figure 5D). We next asked if Aurora-B phosphorylates GFAP or desmin at the sites identified in vitro, using COS-7 cells and transient transfection analyses. As shown in Figure 5E, phosphorylation of GFAP at Thr-7, Ser-13, and Ser-38 but not Ser-8 was detected in interphase COS-7 cells expressing GFAP with Aurora-B and INCENP. The same phosphorylation pattern was observed when the catalytic domain of Rho-kinase (Rho-K-CAT) was used instead of Aurora-B and INCENP (Figure 5E). Next, we determined if desmin is phosphorylated at Ser-11, Thr-16, and Ser-59 by activated Aurora-B in interphase when Aurora-B and INCENP are overexpressed with desmin in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells ectopically expressing desmin, Aurora-B and INCENP were immunostained with 9E10 and an antiphosphodesmin antibody: α-PD11, α-PD16, α-PD59, α-PD75, or α-PD76. As shown in Figure 5 F, phosphorylation of overexpressed desmin at Ser-11, Thr-16, and Ser-59 was observed in cells coexpressing Aurora-B and INCENP, whereas that of desmin-Thr-75 and Thr-76 was not detected. We also examined the phosphorylation of desmin at Thr-16, Thr-75, and Thr-76 in interphase COS-7 cells ectopically expressing Rho-K-CAT. Phosphorylation of desmin at Thr-16, Thr-75, and Thr-76 was observed in interphase cells expressing Rho-K-CAT (Figure 5F). The phosphorylation of desmin at Ser-11 and Ser-59 was not observed in cells expressing Rho-K-CAT. Therefore, Ser-11 and Ser-59 could be the sites phosphorylated by active Aurora-B in cells.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of histone H3, GFAP, and desmin in COS-7 cells expressing Aurora-B activated by INCENP or active Rho-kinase. (A–D) COS-7 cells were transfected with pcDNA-Myc-Aurora-B (A), pCMV-HA-INCENP (B), or both (C and D) and double-stained with antiphospho-H3-Ser-10 (A–C, left panels), antiphospho-H3-Ser-28 (D, left panel), 9E10 (A, C, and D, right panels), and anti-HA (B, right panel). (E) COS-7 cells were transfected with pCMV-GFAP, pcDNA-Myc-Aurora-B and pCMV-HA-INCENP (a–h), or pCMV-GFAP and pEF-BOS-Myc-Rho-K-CAT (i–p). Cells were double-stained with 9E10 (e–h and m–p) and TMG7 (a and i), YC10 (b and j), KT13 (c and k), or KT34 (d and l). (F) COS-7 cells transfected with pCMV-desmin, pcDNA-Myc-Aurora-B, and pCMV-HA-INCENP (a–j) or pCMV-desmin and pEF-BOS-Myc-Rho-K-CAT (k–t) were double-stained with 9E10 (f–j and p–t) and α-PD11 (a and k), α-PD16 (b and l), α-PD59 (c and m), α-PD75 (d and n), or α-PD76 (e and o). Note that antiphosphopeptide antibodies used in the experiments detected corresponding in vivo site-specific phosphorylation in cells. Bar, 20 μm.

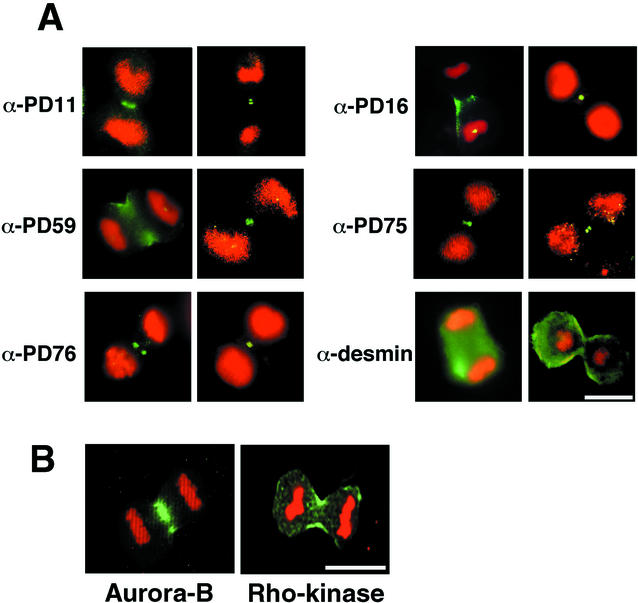

Specific Phosphorylation of Desmin at Ser-11 and Ser-59 at the Cleavage Furrow during Cytokinesis

Based on the foregoing biochemical and immunocytochemical observations that desmin-Ser-11, Thr-16, and Ser-59 are sites phosphorylated by Aurora-B in vitro and that desmin-Thr-16, Thr-75, and Thr-76 are phosphorylation sites by Rho-kinase, the spatial and temporal distributions of the five phosphorylation sites in Saos-2 human osteosarcoma cells were analyzed, using α-PD11, α-PD16, α-PD59, α-PD75, and α-PD76. Under the conditions used, all immunoreactivity of these antiphosphodesmin antibodies was detected only in late mitotic cells and specifically at the cleavage furrow (Figure 6A), but not in interphase cells or in early mitotic cells such as prometaphase or metaphase (unpublished data). When desmin was stained with an α-desmin antibody, which reacts with both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated desmin, the filamentous structure was observed in mitotic daughter cells (Figure 6A) and in interphase cells (unpublished data). Rho-kinase accumulated at the cleavage furrow and Aurora-B was enriched at the spindle midzone during the cytokinesis (Figure 6B). These observations may suggest that desmin filaments are phosphorylated by Aurora-B as well as Rho-kinase, at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis.

Figure 6.

Localization of phosphodesmin, Aurora-B, and Rho-kinase. (A) Fluorescent photomicrographs of mitotic Saos-2 cells stained with α-PD11, α-PD16, α-PD59, α-PD75, α-PD76, or α-desmin (green). Chromosomes were stained with propidium iodide (red). The reactivity of these antiphosphodesmin antibodies was specifically observed at cleavage furrow in cytokinesis. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Mitotic Swiss3T3 cells were stained using antibodies against Aurora-B (Transduction Laboratories) and Rho-kinase. The green color is for kinase immunoreactivity, whereas the red color (propidium iodide) is for chromosomes. Bar, 20 μm.

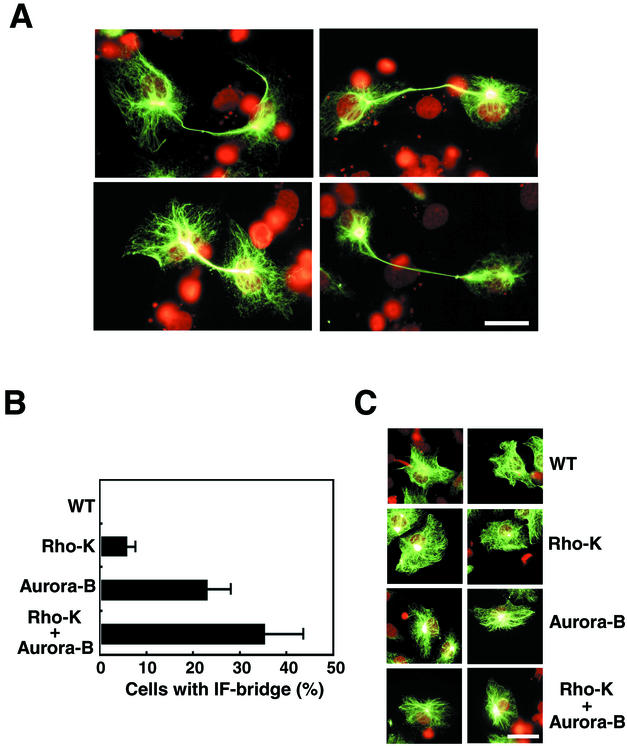

Effects on Cytokinesis of Desmin Mutants at Aurora-B and/or Rho-kinase Phosphorylation Sites

In the next set of experiments, we determined if a desmin mutant at in vitro phosphorylation sites by Aurora-B or Rho-kinase induces IF-bridge formation. We constructed three desmin mutants, in which sites phosphorylated in vitro by Rho-kinase, Aurora-B, or both are changed to Ala or Gly. When the mutants were transiently expressed in T24 cells, the mutant desmin filaments failed to segregate into daughter cells; rather they formed an unseparated bridge-like structure between them (Figure 7A and unpublished data). When we evaluated the percentage of postmitotic IF-bridge–forming cells, ∼7% and ∼23% of the cells expressing mutated desmin at Rho-kinase sites and at Aurora-B sites, respectively, formed a desmin-bridge structure (Figure 7B). Mutations at both Rho-kinase and Aurora-B phosphorylation sites also showed effects, and ∼35% of the transfected cells had the desmin-bridge (Figure 7B). On the contrary, expression patterns of the mutants in interphase cells were indistinguishable from those of wild-type desmin (Figure 7C). Although cells expressing the mutants had a normal morphology at prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase (unpublished data), they did have a striking phenotype after passing through telophase.

Figure 7.

Effects of mutations in desmin at Aurora-B and/or Rho-kinase phosphorylation sites on cytokinesis. (A) IF bridge-like structures in T24 cells expressing a desmin mutant at phosphorylation sites by Rho-kinase and Aurora-B; Thr-16, Ser-59, Thr-75, and Thr-76 are changed to Ala, and Ser-11 is changed to Gly. The desmin immunoreactivity was stained with α-desmin (green). Chromosomes were stained by propidium iodide (red). Bar, 40 μm. (B) Quantification of desmin IF-bridge formation induced by mutations at phosphorylation sites by Rho-kinase (Rho-K), Aurora-B, or both. The percentage of the desmin IF-bridge–positive cells was scored. Data are means ± SEM of at least triplicate determinations. At least 200 cells per each sample were counted and at least three independent experiments were carried out. The two daughter cells linked by one bridge-like structure were counted as one cell. (C) Localization of the wild-type desmin (WT) and the three mutants as in B in interphase T24 cells. The green color represents desmin immunoreactivity. The red color is for chromosomes stained with propidium iodide. Bar, 40 μm.

DISCUSSION

It is assumed that Aurora-B kinase activity is essential for chromosome segregation and cytokinesis. It is crucial to clarify Aurora-B substrates in order to better understand the physiological relevance of Aurora-B. It has been reported that phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser-10 occurs in vitro by purified yeast Aurora homologue, Ipl1p kinase, and is defective in vivo in Ipl mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hsu et al., 2000). In C. elegans and Drosophila, RNAi experiments showed clearly that Aurora-B is required for mitotic histone H3-Ser-10 phosphorylation (Hsu et al., 2000; Adams et al., 2001b; Giet and Glover, 2001). Additionally, it was demonstrated that phosphorylation at Ser-10 of vertebrate histone H3 is also regulated by Aurora-B, determined using a cell-free system of Xenopus egg extract (Murnion et al., 2001). In mammalian cells, we found that Aurora-B phosphorylates histone H3 not only at Ser-10 from late G2 phase to metaphase but also at Ser-28 from prophase to metaphase (Goto et al., 2002). A histone H3-like protein, centromere protein A (CENP-A) was reported to be phosphorylated by Aurora-B (Zeitlin et al., 2001b) and the phosphorylation begins in prophase and reaches maximal levels in prometaphase. CENP-A phosphorylation is lost during anaphase and becomes undetectable in telophase cells (Zeitlin et al., 2001a). Phosphorylation site mutants of CENP-A result in a delay at the terminal stage of cytokinesis (Zeitlin et al., 2001b). These findings suggest that the phosphorylation of CENP-A by Aurora-B has an important role in broad mitotic processes, although the precise molecular mechanism remains to be uncovered.

To better understand molecular mechanisms related to Aurora-B in the mitotic phase, it is important to search for unidentified substrates and to elucidate the physiological significance of their phosphorylation. We reported a novel protein kinase activity that phosphorylates vimentin at Ser-72 during cytokinesis (Yasui et al., 2001), and the kinase was proved to be Aurora-B (unpublished data). On the basis of this finding, we asked if type III IF proteins could be substrates of Aurora-B during cytokinesis. Indeed, Aurora-B phosphorylated GFAP and desmin and the phosphorylation of the two IF proteins remarkably inhibited their filament forming activity in vitro. The sites phosphorylated by Aurora-B were determined to be Thr-7/Ser-13/Ser-38 of GFAP and Ser-11/Thr-16/Ser-59 of desmin and all of these sites were found to be phosphorylated at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis. This evidence may suggest that Aurora-B acts as a novel cleavage furrow kinase responsible for desmin and GFAP phosphorylation during cytokinesis, although the possibility is not ruled out that other kinase(s) with the same substrate specificity may function.

In previous works, we found that Rho-kinase phosphorylates GFAP in vitro and this phosphorylation is observed at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis (Nishizawa et al., 1991; Matsuoka et al., 1992; Kosako et al., 1997; Yasui et al., 1998). Rho-kinase is a target molecule of a small GTPase Rho and has been shown to regulate a variety of cellular processes such as formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions, smooth muscle contraction, myosin fiber organization, and neurite retraction (for review see Machesky and Hall, 1996; Kaibuchi et al., 1999). In the present study, we clarified that in vitro Aurora-B phosphorylation sites of GFAP (Thr-7, Ser-13, and Ser-38) are exactly the same as those for Rho-kinase. On the other hand, in vitro analyses suggest that Ser-59 of desmin is a specific phosphorylation site for Aurora-B and may serve as a pertinent indicator to monitor Aurora-B–specific desmin phosphorylation. We compared the physiological importance of in vitro phosphorylation sites by Aurora-B to those by Rho-kinase in IF protein phosphorylation during cytokinesis, using desmin as a substrate. About 7% of cells expressing desmin mutated at Rho-kinase phosphorylation sites showed a desmin IF bridge between two daughter cells. As for desmin mutated at in vitro Aurora-B sites, ∼23% cells expressing the mutant showed the IF-bridge phenotype. It is tempting to speculate that Aurora-B and Rho-kinase regulate desmin phosphorylation coordinatedly to ensure efficient desmin segregation during cytokinesis. The percentage of cells forming the desmin IF bridge is at most ∼35%, possibly due to 1) the timing of IF-bridge formation varies among cells because there is no complete synchronization or 2) the score may be underestimated because IF-bridge–forming cells that were torn off were no longer counted as positive. From the results obtained in this study, it is possible that continuous furrow ingression during late mitotic phase may increase IFs accessibility not only to Rho-kinase in the plasma membrane of the cleavage furrow but also to another kinase, which phosphorylates Ser-59 of desmin. Aurora-B is a candidate of the kinase. These localized interactions induce cleavage furrow-specific efficient IF protein phosphorylation by both kinases.

Further approaches such as RNAi or genetical analyses are required to identify the kinase responsible for the phosphorylation at Ser59 of desmin as Aurora-B

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Y. Nishi (our laboratory) for help with the electron microscopy. We also thank Dr. M. Serikawa (Nagoya University) for preparing some materials used. This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research and for cancer research from Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sports, and Culture of Japan; and by a grant-in-aid for the 2nd-Term Comprehensive 10-year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan. A.K is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Abbreviations used:

- CaMKII

Ca2+/Calmodulin kinase II

- CENP-A

centromere protein A

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- INCENP

inner centromere protein

- IFs

intermediate filaments

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PP1

type1 protein phosphatase

- Rho-kinase

Rho-associated kinase

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E02–09–0612. Article and publication date are at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E02–09–0612.

REFERENCES

- Adams RR, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. Chromosomal passengers and the (aurora) ABCs of mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2001a;11:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01880-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RR, Maiato H, Earnshaw WC, Carmena M. Essential roles of Drosophila inner centromere protein (INCENP) and aurora B in histone H3 phosphorylation, metaphase chromosome alignment, kinetochore disjunction, and chromosome segregation. J Cell Biol. 2001b;153:865–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff JR, et al. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 1998;17:3052–3065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff JR, Plowman GD. The Aurora/Ipl1p kinase family: regulators of chromosome segregation and cytokinesis. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:454–459. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop JD, Schumacher JM. Phosphorylation of the carboxyl terminus of inner centromere protein (INCENP) by the Aurora B kinase stimulates Aurora B kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27577–27580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200307200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JE, Opal P, Goldman RD. Intermediate filament dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90065-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Weber K. Intermediate filaments: structure, dynamics, function, and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:345–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R, Glover DM. Drosophila aurora B kinase is required for histone H3 phosphorylation and condensin recruitment during chromosome condensation and to organize the central spindle during cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:669–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R, Prigent C. Aurora/Ipl1p-related kinases, a new oncogenic family of mitotic serine-threonine kinases. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:3591–3601. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.21.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giet R, Prigent C. The Xenopus laevis aurora/Ip11p-related kinase pEg2 participates in the stability of the bipolar mitotic spindle. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:145–151. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover DM, Leibowitz MH, McLean DA, Parry H. Mutations in aurora prevent centrosome separation leading to the formation of monopolar spindles. Cell. 1995;81:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto H, Kosako H, Tanabe K, Yanagida M, Sakurai M, Amano M, Kaibuchi K, Inagaki M. Phosphorylation of vimentin by Rho-associated kinase at a unique amino-terminal site that is specifically phosphorylated during cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11728–11736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto H, Yasui Y, Nigg EA, Inagaki M. Aurora-B phosphorylates Histone H3 at serine28 with regard to the mitotic chromosome condensation. Genes Cells. 2002;7:11–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, et al. Mitotic phosphorylation of histone H3 is governed by Ipl1/aurora kinase and Glc7/PP1 phosphatase in budding yeast and nematodes. Cell. 2000;102:279–291. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt T. Cyclins and their partners: from a simple idea to complicated reality. Semin Cell Biol. 1991;2:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada H, Goto H, Tanabe K, Nishi Y, Kaibuchi K, Inagaki M. Rho-associated kinase phosphorylates desmin, the myogenic intermediate filament protein, at unique amino-terminal sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;253:21–25. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada H, Togashi H, Nakamura Y, Kaibuchi K, Nagata K, Inagaki M. Balance between activities of Rho kinase and type 1 protein phosphatase modulates turnover of phosphorylation and dynamics of desmin/vimentin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34932–34939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M, Gonda Y, Matsuyama M, Nishizawa K, Nishi Y, Sato C. Intermediate filament reconstitution in vitro. The role of phosphorylation on the assembly-disassembly of desmin. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5970–5978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M, Matsuoka Y, Tsujimura K, Ando S, Tokui T, Takahashi T, Inagaki N. Dynamic property of intermediate filaments: regulation by phosphorylation. Bioessays. 1996;18:481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Kaibuchi K, Kuroda S, Amano M. Regulation of the cytoskeleton and cell adhesion by the Rho family GTPases in mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaitna S, Mendoza M, Jantsch-Plunger V, Glotzer M. Incenp and an aurora-like kinase form a complex essential for chromosome segregation and efficient completion of cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymkowsky MW. Intermediate filaments: new proteins, some answers, more questions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:46–54. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosako H, Amano M, Yanagida M, Tanabe K, Nishi Y, Kaibuchi K, Inagaki M. Phosphorylation of glial fibrillary acidic protein at the same sites by cleavage furrow kinase and Rho-associated kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10333–10336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosako H, et al. Specific accumulation of Rho-associated kinase at the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis: cleavage furrow-specific phosphorylation of intermediate filaments. Oncogene. 1999;18:2783–2788. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky LM, Hall A. Rho: a connection between membrane receptor signaling and the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:304–310. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)10026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y, Nishizawa K, Yano T, Shibata M, Ando S, Takahashi T, Inagaki M. Two different protein kinases act on a different time schedule as glial filament kinases during mitosis. EMBO J. 1992;11:2895–2902. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer HE, Hoffmann-Posorske E, Korte H, Heilmeyer LMG. Sequence analysis of phosphoserine-containing peptides. Modification for picomolar sensitivity. FEBS Lett. 1986;204:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Kaitna S, Glotzer M. Central spindle assembly, and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity. Dev Cell. 2002;2:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata-Hori M, Tatsuka M, Wang YL. Probing the dynamics and functions of Aurora B kinase in living cells during mitosis and cytokinesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1099–1108. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnion ME, Adams RR, Callister DM, Allis CD, Earnshaw WC, Swedlow JR. Chromatin-associated protein phosphatase 1 regulates aurora-B and histone H3 phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26656–26665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Mitotic kinases as regulators of cell division and its checkpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35048096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Targets of cyclin-dependent protein kinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:187–193. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90101-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa K, Yano T, Shibata M, Ando S, Saga S, Takahashi T, Inagaki M. Specific localization of phosphointermediate filament protein in the constricted area of dividing cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3074–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury C, Nurse P. Animal cell cycles and their control. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:441–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves SA, Helman LJ, Allison A, Israel MA. Molecular cloning and primary structure of human glial fibrillary acidic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5178–5182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roghi C, et al. The Xenopus protein kinase pEg2 associates with the centrosome in a cell cycle-dependent manner, binds to the spindle microtubules and is involved in bipolar mitotic spindle assembly. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:557–572. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JM, Golden A, Donovan PJ. AIR-2: an Aurora/Ipl1-related protein kinase associated with chromosomes and midbody microtubules is required for polar body extrusion and cytokinesis in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1635–1646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimata M, Tsujimura K, Tanaka J, Takeuchi Y, Inagaki N, Inagaki M. Detection of protein kinase activity specifically activated at metaphase-anaphase transition. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:635–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert PM, Roop DR. Molecular and cellular biology of intermediate filaments. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:593–625. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson AF, Hamill DR, Carter JC, Schumacher J, Bowerman B. The Aurora-related kinase AIR-2 recruits ZEN-4/CeMKLP1 to the mitotic spindle at metaphase, and is required for cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1162–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada Y, Tatsuka M, Suzuki F, Yasuda Y, Fujita S, Otsu M. AIM-1: a mammalian midbody-associated protein required for cytokinesis. EMBO J. 1998;17:667–676. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Yu L, Bowen J, Gorovsky MA, Allis CD. Phosphorylation of histone H3 is required for proper chromosome condensation and segregation. Cell. 1999;97:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y, Amano M, Nagata K, Inagaki N, Nakamura H, Saya H, Kaibuchi K, Inagaki M. Roles of Rho-associated kinase in cytokinesis; mutations in Rho-associated kinase phosphorylation sites impair cytokinetic segregation of glial filaments. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1249–1258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y, Goto H, Matsui S, Manser E, Lim L, Nagata K, Inagaki M. Protein kinases required for segregation of vimentin filaments in mitotic process. Oncogene. 2001;20:2868–2876. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin SG, Barber CM, Allis CD, Sullivan KF. Differential regulation of CENP-A and histone H3 phosphorylation in G2/M. J Cell Sci. 2001a;114:653–661. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin SG, Shelby RD, Sullivan KF. CENP-A is phosphorylated by Aurora B kinase and plays an unexpected role in completion of cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. 2001b;155:1147–1157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]