Abstract

Purpose: This research sought to determine use of online biomedical journals and databases and to assess current user characteristics associated with the use of online resources in an academic health sciences center.

Setting: The Library of the Health Sciences–Peoria is a regional site of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Library with 350 print journals, more than 4,000 online journals, and multiple online databases.

Methodology: A survey was designed to assess online journal use, print journal use, database use, computer literacy levels, and other library user characteristics. A survey was sent through campus mail to all (471) UIC Peoria faculty, residents, and students.

Results: Forty-one percent (188) of the surveys were returned. Ninety-eight percent of the students, faculty, and residents reported having convenient access to a computer connected to the Internet. While 53% of the users indicated they searched MEDLINE at least once a week, other databases showed much lower usage. Overall, 71% of respondents indicated a preference for online over print journals when possible.

Conclusions: Users prefer online resources to print, and many choose to access these online resources remotely. Convenience and full-text availability appear to play roles in selecting online resources. The findings of this study suggest that databases without links to full text and online journal collections without links from bibliographic databases will have lower use. These findings have implications for collection development, promotion of library resources, and end-user training.

INTRODUCTION

Remote access to online catalogs and bibliographic databases has altered library use patterns over the past decade. Library statistics show fewer patrons entering the library as more resources become available online and patrons gain access from their desktops [1]. Many academic institutions are currently building substantial collections of full-text journals and continue to increase access to various online databases. Because these resources come at a great cost, it becomes important to understand database and full-text journal use among university patrons and the characteristics accompanying today's remote and inhouse library users. Increased access to computers, the Internet, online databases, and full-text journals necessitates reassessing online use patterns and user characteristics.

The paper reports on the findings of a survey distributed to faculty, students, and residents to determine use of the online resources and characteristics of current users. Some specific questions address whether computer literacy still plays a factor in determining who uses online resources, whether users of the online databases are also users of the online journals, whether there are differences in the use of resources among the various user groups, what users' primary information sources are, where users access the online resources, and whether users are fully aware of the multitude of resources available.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies have found that the implementation of online databases affects internal library use, particularly when databases can be accessed through the Internet. Hurd and Weller noted a shift to online databases (MEDLINE and Current Contents) by chemists when the databases became available through the network at no charge to users [2]. Another study by Curtis, Weller, and Hurd also found that health sciences faculty preferred accessing electronic databases from their offices rather than going to the library [3]. Grefsheim, Franklin, and Cunningham determined that computer use correlated negatively with time spent in libraries and journals read but positively with the use of online databases such as MEDLINE [4]. As early as 1991, when the Grefsheim, Franklin, and Cunningham study was published, there was evidence, even for those researchers who were not regular users of computers, for “a trend away from subscribing to print products in favor of online retrieval of needed current-awareness information” [5].

The introduction of online journals has further influenced this shift toward online retrieval. Early studies that examined the influence of full-text CD-ROMs on the use of the print collection consistently found a decrease in print material use [6, 7]. Students preferred to retrieve and print the full text of articles from CD-ROM systems, regardless of whether the library owned the journals in print [8].

More recent studies examining the impact of remote access to full-text journals showed similar trends. Several studies have found print journal usage in academic libraries has decreased significantly since the introduction of online journals [9–11]. De Groote and Dorsch examined the impact of online journals on the use of the print collection in a health sciences library and found that print journal usage decreased significantly with the introduction of online journals, even for journals available only in print [12].

Another study examined staffing demands to measure the impact of online journals on the library [13]. Reduced staffing was required for reshelving, maintaining stacks, user photocopying, collecting use data, checking in journals, claiming, and binding. However, increased staffing was required in the information services department for reference at the desk, instruction, promotion, and preparation of documentation.

When the shift from print indexes to online databases began in the late 1980s, computer literacy appeared to play a role in the use of online resources. Grefsheim, Franklin, and Cunningham concluded, “the factors that positively influenced computer use among [the participants in one study] were keyboard literacy, previous experience with computers, ready availability of computerized information sources, peer pressure, and the level of computerization in the field or institution in which they work” [14]. A 1989 study by Marshall found that those health professionals who had interests in research had taken online training and those who were defined as computer literate (owned a computer) were more likely to do their own searching [15]. In addition, health care workers who had computers at home were more likely to be computer literate than those who only had computers in their office, where, in most cases, other office staff made primary use of the terminals. Marshall also discovered that the more time a health care worker spent caring for patients, the less likely the individual would see value in end-user searching.

Studies have also examined where various user groups traditionally obtained information. A study examining biotechnologists' information use patterns found that 85% of these researchers obtained information from their personal journal collections, while only 45% obtained information from their health sciences library [16]. A study by Curtis, Weller, and Hurd (1997) reported that 78% of health sciences faculty relied on personal subscriptions as sources of journal articles, but 85% also went to the library to photocopy articles [17].

Cogdill and Moore observed that medical students tended to rely primarily on textbooks for their information needs [18], while one of the last places students looked for information was the journal literature. However, when the students were faced with a question related to treatment, they were more likely to perform searches in MEDLINE rather than depend solely on the medical textbooks. A study of the library use and information-seeking behavior of veterinary medicine students found these students relied on class handouts, textbooks, classmates, and instructors before using online databases to locate current information [19].

BACKGROUND

The Library of the Health Sciences–Peoria is a site library of the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Library with a print journal collection of approximately 350 titles. Beginning in 1999, UIC site licenses have given students and faculty affiliated with UIC–Peoria access to more than 4,000 online full-text titles through the Internet. At the time of the study, only about ninety of the 350 print journals were uniquely available in print, while the rest of the collection was available in print and online. In addition, since 1999, licenses to the following major databases were acquired: Web of Science, Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EBM Reviews, and MD Consult. Ovid MEDLINE linked directly to approximately 200 journals available through Journals@Ovid. Access to databases such as Current Contents, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, PubMed, and Internet Grateful Med (IGM) had been available prior to 1999. During the period of the study, the UIC library had not implemented links to the library catalog or other full-text providers through any of the Ovid databases. In addition, PubMed link-outs to full text were relatively new. The primary way for users to gain access to full-text journals at UIC was through an online alphabetic journal list, where users would click on the aggregator name to gain access to the journals. The UIC–Peoria library had also produced a printed journal list that indicated the aggregator to use to gain online access to the journals.

Unrestricted access to the library's online resources was available to all users from the library and campus office computers. Remote access to these resources required obtaining a UIC Net ID and password, and all participants qualified to obtain user names and passwords.

METHOD

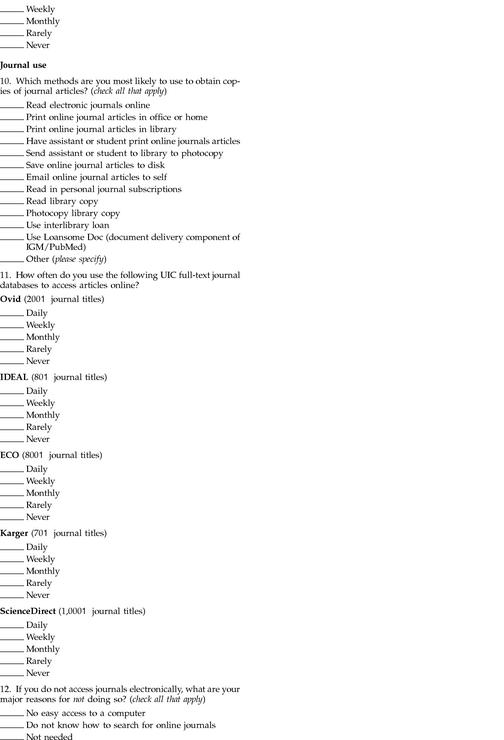

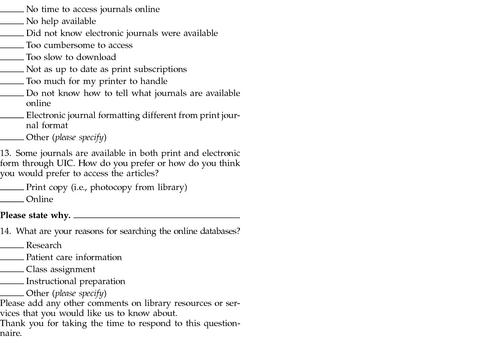

To determine online and print use of the library's online and print resources, a survey was developed. The survey was designed to assess online journal use, traditional journal use, database use, computer literacy levels, and other library user characteristics (Appendix). Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained for the survey. A pilot test of the survey was done, and several questions were changed as a result. In November 2000, the survey was distributed through campus mail to all faculty, residents, and students of the Colleges of Medicine and Nursing at the Peoria campus. The survey was distributed to faculty, residents, and students to determine differences among the various user groups. A cover letter explained the reasons the survey was being conducted, that participation was voluntary, and that anonymity was assured. A training request form asking if more information or training on various databases and software was desired accompanied the survey. Respondents were instructed to return the training request form separately from the survey. Questionnaires were coded to sort respondents by group and to track survey returns. A total of 471 surveys were distributed: 137 to medical and nursing faculty, 134 to medical students, 40 to graduate nursing students, and 160 to residents. A second copy of the survey was sent to nonrespondents approximately four weeks after the deadline, and a third copy was sent after the second deadline had passed. Data from the returned surveys were analyzed with SPSS.

For the purpose of the present study, computer literacy was measured by the following criteria: easy access to a computer connecting to the Internet from home, work, or school and frequency of computer use. Those individuals with a computer connected to the Internet at home and at work or school and who used a computer daily were considered the most computer literate. To determine computer literacy, responses for questions 1 and 2 were awarded a point system ranging from 0 to 3, with 3 being the highest score. For example, a score of 3 was awarded for having a computer with Internet access (question 1) or for using a computer at least once a day (question 2). A score of 0 was given to respondents with no convenient access to a computer or rare or no use of a computer. The scores from questions 1 and 2 were combined for an overall computer literacy score.

RESULTS

A total of 188 (41%) of the 471 surveys originally mailed out were returned: 61 from the medical and nursing faculty (45%), 50 from the medical students (37%), 24 from the graduate nursing students (60%), and 53 from the residents (33%).

Survey results provided information about use of computers and the Internet by faculty, students, and residents. All but 1.5% of the students, faculty, and residents reported having convenient access to a computer connected to the Internet. Sixty-six percent had convenient access to the Internet from both their office or school and home. Only 1% of those surveyed never used a computer, 76% used a computer daily, 18% used a computer weekly, and 5% used a computer monthly. Only 1% indicated they never searched the Internet. Seventy-six percent of survey respondents indicated they knew the library had its own Web page. Fifteen percent of those surveyed did not have a UIC Net ID and password and, therefore, could not gain access to UIC's online library resources remotely.

No significant correlations were found between computer literacy (easy access to the Internet and frequency of computer use) and either searching MEDLINE or accessing the online journals. In other words, computer use and Internet access had no apparent relationship to the use of MEDLINE or full-text journals. Because computer literacy was not significantly correlated with either the use of MEDLINE or full-text journals, separate analyses were performed with questions 1 and 2 for MEDLINE and full-text journal use. No significant correlations were found among these four analyses either.

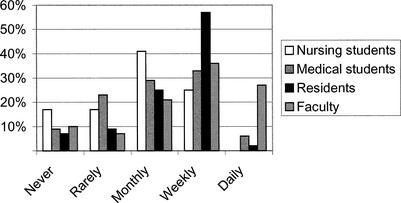

Survey data demonstrated how often users searched the various online databases. The majority of those surveyed (93%) personally searched the online databases. A summary of MEDLINE (PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE) searching is presented in Figure 1. The data showed that 53% of the users searched MEDLINE at least once a week and 6% never searched MEDLINE. The other databases showed much lower usage: 29% never searched MD Consult, 73% never searched CINAHL, 73% never searched Current Contents, 75% never searched PsycINFO, 74% never searched Web of Science, 82.4% never searched International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and 56% never searched the evidence-based medicine (EBM) databases.

Figure 1.

Frequency of MEDLINE use by user group

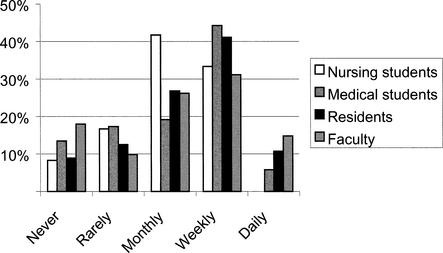

The survey also queried users on the use of the full-text journal collections. Several full-text journal collections were available to students, faculty, and residents. The use of Journals@Ovid full-text (240 full-text journals) by user group is presented in Figure 2. Forty-seven percent of faculty, students, and residents used Journals@Ovid at least once a week, compared to 13% who never used it. The Mann-Whitney Test showed faculty were significantly more likely to access Journals@Ovid than either the medical students (z(112) = −2.771 (P < 0.05)) or residents (z(117) = −2.237 (P < 0.05)). There was a significant positive correlation between the frequency of MEDLINE searching and the frequency of accessing Journals@Ovid (Spearman rho = 0.752, P < 0.01). In other words, the more individuals searched MEDLINE, the more likely they were to access Journals@Ovid.

Figure 2.

Frequency of Journals@Ovid use by user group

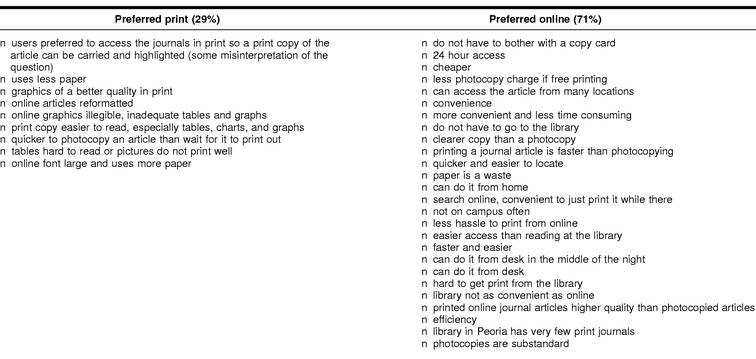

Seventy-five percent of survey respondents never used any of the other full-text databases (over 2,000 online journals), including journals accessed through ECO, IDEAL, Karger, and ScienceDirect (Elsevier). Only 6% of all respondents indicated that they used these full-text databases once a month or more. Users were also asked what method of access they preferred when journals were available both in print and online format. Seventy-one percent indicated that they preferred to access journals online when possible. Reasons for user preferences are provided in Table 1.

Table 1 User preference for accessing journal articles: print versus online

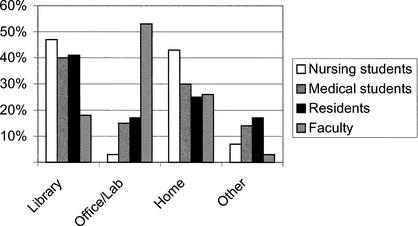

Survey results provided information on the locations from which users accessed the online resources, and results varied among user groups (Figure 3). A low percentage of faculty (18%) used the library to access online resources but instead accessed these resources from their offices (53%). On the contrary, nursing students (47%), medical students (40%), and residents (41%) appeared to be heavy users of the library for access to online resources. Nursing students also accessed the online journals frequently from home (70%). Only 16% of users relied solely on the library to access the online resources, in contrast to 39% of users who never entered the library to access online resources. Sixty-nine percent of the faculty reported never entering the library to access the online resources.

Figure 3.

Locations of online resources access by user group

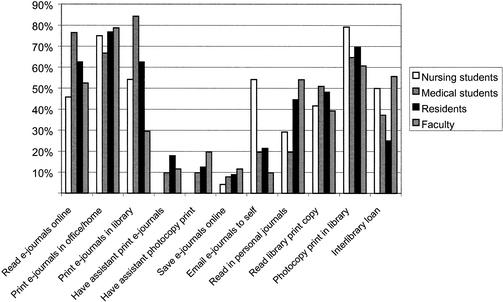

Respondents were also surveyed on mode of access to journal articles (Figure 4). Reading full-text journals online (61%), printing full-text journals in office or home (74.5%), printing online journals in library (57%), and photocopying library print journals (66%) were the most common answers. Medical students were more likely to read full-text journals online (76.5%), print full-text journals in the library (84%), and read a library print copy (51%) than the other user groups. Nursing students were more likely to email full-text journal articles to themselves (54%) or photocopy a journal in the library (79%) than the other user groups. Faculty were more likely to print full-text articles in their offices (79%), read articles in their personal journal subscriptions (54%), and use interlibrary loan (56%) than the other user groups. Correlations using Spearman rho were conducted for each of the following journal article modes of access points: print online journal in office or home, print online journal in library, read personal journal copy, and photocopy library copy. A significant positive correlation was found between printing online journals in the library and photocopying journals in the library (Spearman rho n = 0.208, P < 0.05). If users photocopied library articles, they were also more likely to print online journal articles in the library.

Figure 4.

Ways journal articles are accessed by user group

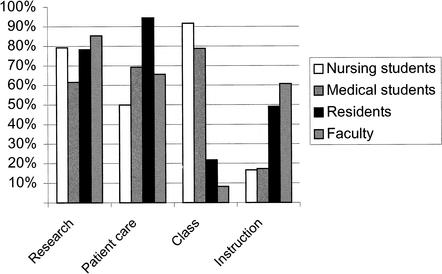

Users were also asked the reasons (research, patient care, instruction, class work) for which they accessed the online resources (Figure 5). Seventy-six percent of total respondents indicated that they accessed the online resources for research purposes, while 72% indicated that they used the online resources for patient care. Faculty accessed the online databases most frequently for research (85%) and for instructional purposes (60.7%). Residents accessed the online resources the most for patient care (94.5%), and nursing students accessed the online resources most often for class preparation (92%). Seventy-nine percent of the medical students accessed the online resources for class assignments.

Figure 5.

Reason for using online databases

DISCUSSION

Computer literacy, in this study, is not a factor in whether users searched online databases. Computer literacy levels certainly have altered over time, and it may be that a different definition of “computer literacy” is now needed. A 1995 survey of health sciences faculty at UIC–Chicago reported 51.6% of respondents used email and 48.1% used the Internet [20]. In this study, conducted in 2000, 99% of those surveyed searched the Internet and used computers. Earlier studies showed that computer use and access to the Internet, or in other words “computer literacy,” had a correlation with online database use [21, 22]. This study demonstrates that acceptance and use of computers and the Internet are widespread among members of an academic health sciences community but are not necessarily correlated with the use of online bibliographic resources.

Several indicators point to low awareness of available online databases or full-text journals. One indicator is the low use of databases other than MEDLINE. Although medical faculty would be expected to use MEDLINE as their primary database, low use of the other databases is a concern. Presumably, some of the databases such as Web of Science would be of great benefit to those individuals involved in research. Users may not have used the other resources because of a lack of awareness of the databases or a lack of knowledge regarding the scope of the databases. Alternatively, users may not have used the other databases because all their needs were met with MEDLINE. Respondents were not asked to specify whether they searched Ovid MEDLINE or PubMed; however, the high use of Journals@Ovid and low use of other full-text journal collections suggested that they used the Ovid MEDLINE interface.

The reported low use of online journals outside those in the Journals@Ovid collection also raises concerns regarding the awareness of available full-text journals. Survey comments such as complaints about reformatted journal articles, resized graphics, and increased paper use supported the conclusion that users were primarily aware of the Ovid journals. At the time of the study, Journals@Ovid did not use portable document format (PDF) for any articles, unlike most of the other journal collections, which might account for some of the complaints.

Several reasons could explain why users did not indicate the use of journal collections other than Ovid. Ovid MEDLINE was the first database with direct links to full-text to be offered at the study institution, and users might have thought the journals in Journals@Ovid were the only full-text journals available. In addition, Ovid MEDLINE was available before PubMed, and users might have been reluctant to learn a new search interface. PubMed link-outs were relatively new at the time of the study, and it could be that some users searching PubMed did not realize an extra step was required to display the link-out buttons to full text or did not notice which vendor was providing full text if the link-out was discovered. It could be argued that users were not aware when they accessed full-text journals other than Ovid. However, the way online journal access was configured at UIC at the time of the study, it was unlikely that users would not be aware of the journal aggregator as the aggregator name was clicked to gain access to online journals. It could be that users were simply unaware that an online journal list existed linking to the aggregator that provided the full-text journal. Other users might have been aware of the other full-text journals but did not wish to expend the effort to exit the database to enter the other full-text databases to obtain articles. Perhaps “the path of least resistance” played a role in online journal selection. Anecdotal evidence from the reference desk supported this assumption. Many users, students and faculty, have admitted to using Ovid because of the ease of the search interface and the seamless links to highly clinical journals. Some have even admitted that they only use what is available online in Ovid and do not seek out print or other full-text collections, even if their information need has not been satisfied.

MD Consult was another of the more commonly used databases. Like Ovid, MD Consult displays links directly to the full text of more than forty journals. The more frequent use of Ovid MEDLINE and MD Consult suggested that use was in part related to the direct links to full text. This implied that not only did convenience play a role when users chose to access online journals over print, but convenience might also play a role when selecting which online database to use. It should be noted that a large number of the core clinical titles were available full text in Ovid and MD Consult, a factor that might also contribute to the higher use of these two databases among the user groups studied.

The availability of full-text journals online also appeared to have had an impact on the mode of access and location from which journals were used. In this study, 79% of faculty printed online journals from their office or home compared to 54% who read articles in their personal journals and 61% who photocopied library journals. Previous studies found higher reliance on personal journal subscriptions [23, 24]. These findings suggested a trend toward less reliance on personal journal subscriptions and a higher reliance on online journals. Previous reliance on personal journal subscriptions might have been in part due to proximity and time. Faculty access to online journals from offices and homes might be altering this trend to include reliance on online journals in addition to personal journal subscriptions. No correlation was found between using online journals and reading personal journal subscriptions. This finding suggested that faculty, at this point, have not traded the use of their personal journal subscriptions for the online journals. It is logical that students spend more time in the library than do faculty, because for students the library is the primary access point on campus to resources. In addition, at the time this study was conducted, printing was free while photocopying was fee-based, and this policy could have affected users' choices. The high use of email to send articles by nursing students might be explained by the status of these students. The graduate nursing program at UIC–Peoria attracts many mid-career, part-time students who are only on campus two days a week. For these students, emailing the results of their searches allows them to maximize their productivity while on campus.

CONCLUSIONS

Awareness and convenience seem to be major factors in the selection of resources, whether print or online. The results of this study indicate that more users prefer online resources to print and that many users access these resources remotely. However, they use only a small portion of the resources available to them. Users tend to select a limited number of databases and seem to be unaware of the availability of databases other than those they use regularly. Further research is needed to determine if users were in fact unaware of the resources available to them or if users were aware of the resources but did not see them as useful in fulfilling an information need. Promotion, education, and organization may all be factors to consider to maximize patron use of the library resources.

Challenges remain in balancing print and online resources to meet the needs of various groups, organizing resources, and educating users to select resources based on information needs rather than format or convenience. The findings of this study suggest that databases without links to full text and online journal collections without links from a bibliographic database will have lower use. Promotion of the online catalog as the point of access to both print and online journals will encourage use based on need rather than convenience. Likewise, libraries also need to consider selecting databases that provide full-text links to their online collections in a seamless manner. Furthermore, libraries need to be proactive in facilitating access to the library catalog or full-text journals directly from bibliographic databases. Since the study, Ovid Weblinks has been implemented to link citations in Ovid to the UIC catalog. PubMed's library link-out has also been implemented. When users display results in PubMed's abstract format, information is displayed regarding UIC's online and print holdings. PubMed's link-out feature has affected instruction at the institution in this study. PubMed is often promoted over Ovid MEDLINE due to the significant increase in the number of journals that can be accessed directly from PubMed, compared to Ovid MEDLINE.

The organization of online resources is also of paramount importance to online journal and database use. Although most respondents indicated they knew the library had a home page, they were not asked if they used the page to navigate the library's resources. Lack of use or awareness of the library home page could have prevented some users from quickly accessing available resources. Further research is needed to determine what role in this study the library's Web pages played in facilitating access to the online resources.

The need to teach the scope and purpose of resources must be reinforced as a priority in instructional programs. Limited instruction time means that librarians concentrate on key resources and have little time to explore specialized or supplementary databases. Reliance on desktop access reduces the need for users to come to the library. This fact presents further challenges for instruction and promotion of resources, because users might not think to approach a librarian about training. In fact, Adams and Bonk found that lack of training and lack of information about databases were perceived as the top two obstacles to the use of electronic information and technologies by faculty respondents in a large academic center [25]. Web-based instruction, online point-of-use guides, virtual library tours, self-paced tutorials, and real-time online access to reference services should become part of the library instructional program to support users at their desks. Outreach and aggressive promotion of resources remain a challenge for health sciences librarians. New approaches might include onsite training of remote users, special events to introduce new resources, or distribution of information via institutional electronic mailing lists. It is interesting to note that although many respondents returned the training request form, indicating a realization of lack of knowledge about resources, few replied to the follow-up call offering additional instruction or came to a class as a direct result of the survey.

Findings of this study confirm that computers and the Internet are now ubiquitous for members of an academic health sciences community. However, information literacy is not. As libraries provide more online resources, librarians should take steps to make sure users are aware of these resources and teach users their importance in filling information needs. The online information environment is not static; rather, frequent changes in content, search engines, and access points make for a constantly moving target.

The results of this study also demonstrate that the use of the resources is varied among the user groups. User groups differ in their methods of access and in their frequency of use of online resources. Perhaps most importantly, differences exist in the information needs and the reasons for accessing the online resources among the user groups. These are all factors to keep in mind when considering training issues and promoting library resources.

The era of online information, although in its infancy, has been embraced by users. Many questions are yet to be formulated about the effect online collections will have on libraries. However, some of the questions that remain to be answered sound very familiar. How do librarians best organize resources to meet users' information needs? How do libraries integrate new formats with existing formats? How do librarians obtain a meaningful measure of what resources are used, by whom, and how much? How do librarians educate users about resources? How do librarians ascertain if collections are meeting the information needs of diverse clientele? Supporting online collections involves functions across the library: collection development, information services, access services, and technical services. The success of online journals and databases will depend on how well these various functions come together to produce a system of immediate and seamless access to online information.

The findings in this study confirm that a large percentage of users in an academic health sciences environment prefer online resources to print. Faculty, and to a lesser extent students, access the resources remotely rather than in the library. Furthermore, users select a small number of available online resources and seem unaware of the broader spectrum of available resources. Convenience seems to play a major role in selecting resources, whether print or online. Changing use patterns will require librarians to examine collection development policies, instructional programs, and reference services to meet information needs in the online environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their thanks to Jean Aldag, Ph.D., for statistical assistance and Ann Carol Weller for her thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Appendix

Use of electronic journals and online databases

Contributor Information

Sandra L. De Groote, Email: sgroote@uic.edu.

Josephine L. Dorsch, Email: jod@uic.edu.

REFERENCES

- Scherrer CS, Jacobson S. New measures for new roles: defining and measuring the current practices of health sciences librarians. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Apr; 90(2):164–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd JM, Weller AC. From print to electronic: the adoption of information technology by academic chemists. Sci & Tech Libr 1997;16(3–4):147–70. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KL, Weller AC, and Hurd JM. Information-seeking behavior of health sciences faculty: the impact of new information technologies. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):402–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bane AF. Business periodicals Ondisc: how full-text availability effect the library. Computers in Libraries 1995;15(5):54–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pessah R, Venturella K. Document delivery: St. John's University's experience with full-text services. Libr Software Rev. 1995 Winter; 14(4):212–4. [Google Scholar]

- Pessah R, Venturella K. Document delivery: St. John's University's experience with full-text services. Libr Software Rev. 1995 Winter; 14(4):212–4. [Google Scholar]

- De Groote SL, Dorsch JL. Online journals: impact on print journal usage. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Oct; 89(4):372–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SA. Electronic journal usage at Ohio State University. Coll Res Libr. 2001 Jan; 62(1):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Morse DH, Clintworth WA. Comparing patterns of print and electronic journal use in an academic health science library. Issues Sci Technol Libr [Internet] 2000 Fall(28). [cited March 2001]. <http://www.library.ucsb.edu/istl/00-fall/refereed.html>. [Google Scholar]

- De Groote SL, Dorsch JL. Online journals: impact on print journal usage. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Oct; 89(4):372–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery CH, Sparks JL. The transition to an electronic journal collection; managing the organizational changes (at Drexel University). Serials Review 2000;26(3):4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG. Characteristics of early adopters of end-user online searching in the health professions. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Jan; 77(1):48–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KL, Weller AC, and Hurd JM. Information-seeking behavior of health sciences faculty: the impact of new information technologies. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):402–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogdill KW, Moore ME. First-year medical students' information needs and resource selection: responses to a clinical scenario. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Jan; 85(1):51–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer NL, Wiese WH, and Leysen JM. Library use and information-seeking behavior of veterinary medical students revisited in the electronic environment. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998 Jul; 86(3):346–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KL, Weller AC, and Hurd JM. Information-seeking behavior of health sciences faculty: the impact of new information technologies. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):402–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG. Characteristics of early adopters of end-user online searching in the health professions. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Jan; 77(1):48–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefsheim S, Franklin J, and Cunningham D. Biotechnology awareness study, part 1: where scientists get their information. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan; 79(1):36–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KL, Weller AC, and Hurd JM. Information-seeking behavior of health sciences faculty: the impact of new information technologies. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1997 Oct; 85(4):402–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JA, Bonk SC. Electronic information technologies and resources: use by university faculty and faculty preference for related library services. Coll Res Libr. 1995 Mar; 56(2):119–31. [Google Scholar]