Abstract

According to recent reports, some cancer types exhibit nonrandom allele loss at codon 72 in exon 4 of the p53 gene [coding for proline (72Pro) or arginine (72Arg)]. To clarify this phenomenon for colorectal cancer and to find out if this preferential loss might have any functional significance, p53 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and p53 mutations were investigated in a group of 61 colorectal cancers and 28 liver metastases, and were correlated with clinicopathologic factors. A comparison of a patient's blood codon 72 status with a healthy control group did not reveal an enhanced risk of developing colorectal tumors for one of the two isoforms. p53-LOH and p53 mutations were found in 62.2% and 39.4% of primary tumors, respectively, and in 57.9% and 25% of hepatic metastases, respectively. In 14 heterozygous cases showing exon 4-LOH, only the 72Pro allele was lost and the retained 72Arg was preferentially mutated. In general, p53 mutations were significantly associated with the 72Arg tumor status (P < .001). Distal tumors showed allelic losses of the p53 gene more commonly than proximal tumors (P = .054). The prevalence of 72Arg increased in frequency with higher Dukes stage (P = .056). We suggest that either the preferential loss of 72Pro or the mutation of the 72Arg in colorectal cancer and hepatic metastases is associated with malignant potential and might reflect carcinogenic exposure, particularly in the distal part of the large intestines.

Keywords: Codon 72 polymorphism, p53-LOH, p53 mutation, colorectal cancer, allelic loss

Introduction

The p53 tumor-suppressor gene, located on chromosome 17p13, is one of the most commonly mutated genes in all types of cancer [1,2]. To date, several polymorphisms in the wild-type p53 gene locus have been described [3]. The most important p53 polymorphism is the restriction fragment length polymorphism in codon 72 of exon 4 coding for proline (72Pro: CCC) or arginine (72Arg: CGC). This polymorphism has been reported to be associated with some tumor types [Pro: bladder cancer [4], lung cancer [5,6]; Arg: hepatocellular carcinoma [7], cervical cancer [8], human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cervical cancer [9].

Functional differences between the two polymorphic forms of the wild-type protein have been described previously [2]. The 72Arg form of wild-type p53 was found to be more sensitive to proteolysis mediated by the E6 protein of the human papillomavirus than the wild-type 72Pro [10]. Moreover, the codon 72 status of tumor-associated p53 mutants decides whether they form heterodimers with p73 or not [11]. Nonrandom allele loss at codon 72 has recently been reported for squamous cell cancers [11–15]. Furthermore, a better clinical response following cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy has been shown for advanced head and neck cancers expressing 72Pro mutants in comparison to those expressing 72Arg mutants [16]. To the best of our knowledge, data on colorectal cancer are presently not available. Although there are several studies dealing with p53 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) [17–21], colon cancers have not yet been investigated for a preferential loss of one allele. Exon 4 polymorphism thus appears to be a system that is useful in double respect, namely, for studying the frequency of p53-LOH and for addressing the question of polymorphism. In this study, we used a new rapid one-step real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a LightCycler to analyze the polymorphism [15].

This study was conducted: 1) to test the frequency of p53-LOH and p53 mutations in a group of colorectal carcinomas and liver metastases, and to correlate the genetic findings with clinicopathologic factors; 2) to answer the question of whether one allele is preferentially lost in the case of LOH; 3) to correlate p53 mutations and p53-LOH with 72Arg tumor status; and 4) to test the prevalence of p53 polymorphism at codon 72 compared to a healthy control group.

Materials and Methods

Primary Tumors

The tumor group included 61 patients who had undergone colorectomy for sporadic colon cancer over the last 4 years. The exclusion criteria were familial adenomatous polyposis, simultaneous occurrence of adenomas, and other previous or synchronous adenocarcinomas. The average age of the patients was 63 years (range, 41–89 years). There were 33 males and 28 females. The tumor was localized in the right colon (cecum, ascending) in 29 cases, in the transverse colon in 1 case, and in the left colon (descending, sigmoid, rectum) in 31 cases. Tumors were graded and staged on routinely processed, formalin-fixed, and paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Six tumors were staged Dukes A, 13 as Dukes B, and 42 as Dukes C [22 with Dukes C1 (TN1M0) and 20 with Dukes C2 (TN>1M>0)]. Five tumors were well differentiated, 47 tumors were moderately differentiated, and 9 were poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas. Both blood and tumor tissue were obtained immediately after surgical resection (tumor tissue was obtained by the pathologist C.B. from the center of the lesion avoiding necrotic areas), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -70°C until DNA extraction. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections obtained from frozen specimens were examined to verify representativity.

Metastases

We investigated another group of 28 liver metastases. In six patients, tissues of the metastases and the corresponding primary tumor were available. Blood and tumor tissue were always collected for DNA analysis. The mean age of the group with metastases was 61 years (range, 41–78 years). Twenty-two tumors were moderately differentiated, and six were poorly differentiated.

Normal Control Group

Blood from 85 Central European Caucasians with homogeneous age and sex distribution (average, 45.6 years; range, 22–88 years; 42 males and 43 females) served as normal control.

DNA Extraction

Tumor and blood DNA were extracted using the proteinase K-phenol-chloroform extraction protocol as previously described [22].

PCR

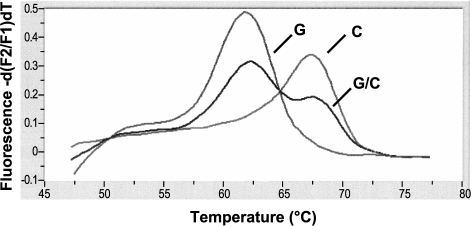

For PCR of exon 4 of the p53 gene, we used the Light-Cycler-DNA Master Hybridization Probes Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) as described previously by Schneider-Stock et al. [15]. Briefly, the LCRed hybridization probe was designed to detect the C-variant. If G is present, the resulting mismatch with the probe destabilizes the sample probe hybrid, and this effect is further enhanced by inserting two additional inositol bases into the probe, yielding a melting temperature that is lower in mismatched (Tm = 62.5°C) than in normal-matched cases (Tm = 69°C). The different melting curve profiles (Figure 1) allow for exact genotyping without post-PCR handling.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the melting temperature to identify the genotype variant at codon 72 in exon 4 of the p53 gene. If G (72Arg) is present, the resulting sample probe mismatch yields a lower melting temperature (62.5°C) than the normal-matched cases (C: 72Pro, 68.5°C). Two peaks are visible in heterozygous cases (C/G).

p53 Intron 1 Polymorphism

To further enhance the informativity for p53-LOH, a second p53 polymorphic marker was analyzed. The intron 1 region of the p53 gene [Alu repeat with (AAAAT)n] was amplified using the following touchdown PCR: 95°C for 5 minutes, 20 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 66°C for 10 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds, with a stepwise decrease of 2°C in each fifth cycle, and, finally, 30 cycles at 95°C for 45 seconds, 58°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute. Primer sequences were sense 5′-ACTCCAGCCTGGGCAATAAGAGCT-3′ and antisense 5′ACAAAACATCCCCTACCAAACAGC-3′. An aliquot of the PCR product was electrophoresed on native 8% polyacrylamide gels, cross-linked with piperazine diacrylamide, and visualized by a silver staining method described by Budowle et al. [23].

An allelic loss was considered in cases when, in comparison with nontumor DNA, the signal of a tumor band disappeared, or signal intensity was reduced by more than 50%. Evaluation was done twice, visually, or by densitometry (VDS; Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) in ambiguous cases.

p53 Mutation Analysis

Mutations in exons 4 to 8 of the p53 gene were determined using PCR-SSCP sequencing analysis as described by Schneider-Stock et al. [24].

Statistics

Statistical analyses were carried out using the chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact test in cross-tables and one-way ANOVA (for comparison of group means). P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant, and P < .10 was regarded as a statistical trend. All statistical tests were two-sided. Calculations were carried out by using the SPSS 9.0 software.

Results

The distribution of p53 codon 72 genotypes (Arg/Arg, Arg/Pro, and Pro/Pro) is discussed as follows.

Control Group Versus Tumor Group (Blood Analysis)

The distribution of the control group was 44.7% for Arg homozygotes (n = 38), 48.2% for Arg/Pro heterozygotes (n = 41), and 7.1% for Pro homozygotes (n = 6). The cancer group (blood) showed a very similar distribution (47.3% for homozygous Arg, 44.1% for Arg/Pro, and 8.6% for homozygous Pro; df = 2, χ2 = 0.366, P = .833; Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the Codon 72 Status in the Blood of Colorectal Cancer, Liver Metastases, and the Healthy Control Group.

| Genotype | Control Group [n (%)] |

Primary Tumors [n (%)] |

Metastases [n (%)] |

P |

| n | 85 | 57* | 26* | |

| Arg/Arg | 38 (44.7) | 26 (45.6) | 13 (50) | |

| Arg/Pro | 41 (48.2) | 26 (45.6) | 12 (46.4) | ns |

| Pro/Pro | 6 (7.1) | 5 (8.8) | 1 (3.6) | |

In six cases, the primary tumor and the corresponding metastasis were investigated.

Blood was collected from 76 patients.

Primary Tumors Versus Metastases (Tissue Analysis)

72Arg tended to predominate in the group of metastases (78.6% for metastases versus 57.4% for primary tumors) and homozygous Pro variants were only rarely found (P = .148; Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between Genetic and Clinicopathologic Data of Patients with Colorectal Cancer.

| Status at Codon 72 | |||||||

| Factor | Total p53-LOH-Positive [n (%)] |

P | n | Arg/Arg [n (%)] |

Arg/Pro [n (%)] |

Pro/Pro [n (%)] |

P |

| Tumor type | |||||||

| Primary | 23/37 (62.2) | 0.615 | 61 | 35 (57.4) | 20 (32.8) | 6 (9.8) | 0.148 |

| Metastasis | 11/19 (57.9) | 28 | 22 (78.6) | 5 (17.9) | 1 (3.6) | ||

| Localization | |||||||

| Right/transverse | 7/16 (43.7) | 0.054 | 30 | 16 (53.3) | 11 (36.7) | 3 (10) | 0.853 |

| Left | 16/21 (76.2) | 31 | 18 (58.1) | 10 (32.3) | 3 (10) | ||

| Age (years) | pos. 63.8 | 0.764 | 63.1 | 64.5 | 63.2 | 0.901 | |

| neg. 61.9 | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 14/19 (73.7) | 0.184* | 28 | 17 (57.4) | 9 (32.1) | 2 (7.1) | 0.783 |

| Male | 9/18 (50) | 33 | 18 (54.5) | 11 (33.3) | 4 (12.1) | ||

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| Well | 2/2 (100) | 0.320* | 5 | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.265 |

| Moderate | 21/30 (70) | 47 | 27 (57.4) | 15 (31.9) | 5 (10.6) | ||

| Poor | 0/5 (0) | 9 | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Dukes stage | |||||||

| A | 3/3 (100) | 0.397 | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50) | 0.056* |

| B | 2/4 (50) | 13 | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| C | 18/30 (60) | 42 | 24 (57.2) | 15 (35.7) | 3 (7.1) | ||

Fisher's exact test.

Correlation with Other Clinicopathologic Data

Dukes A tumors showed a higher frequency of the homozygous Pro variant, whereas there was preference for the 72Arg variant in Dukes B and C tumors (P = .056; Table 2). There was no significant correlation between codon 72 status and sex, age, localization, and tumor grade.

LOH

Tumor tissue and corresponding blood were collected from a total of 76 patients. Informativity of exon 4 polymorphism were 33 of 76 (43.5%) and 45 of 76 (59.2%) for intron 1 polymorphism. Considering both polymorphisms together, informativity increased to 73.7% (56 of 76 tumors). Twenty cases were excluded because of noninformativity for both polymorphic markers.

Primary Tumors Versus Metastases

Considering the informative cases, 34 of 56 cases (60.7%) showed allelic losses at the p53 gene [23 of 37 primary tumors (62.2%) and 11 of 19 metastases (57.9%)] (Table 2). Thus, for the next analyses, the two groups were pooled and considered together.

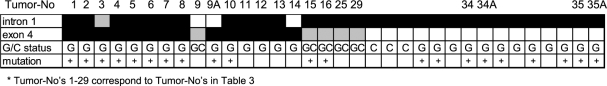

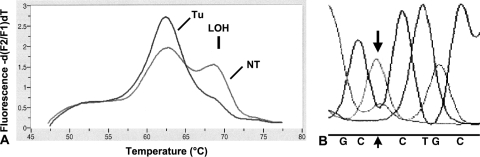

Of the 45 informative cases for intron 1 polymorphism, 32 tumors (71.1%) showed allelic losses. Fourteen of 33 informative cases (45.5%) showed allelic losses for exon 4 polymorphism. All 14 cases with exon 4-LOH exclusively showed losses of 72Pro, whereas loss of the 72Arg was never found (Table 3). To validate the new method, all 14 exon 4-LOH cases were confirmed by using the classic restriction digest with BshI (AGS, Heidelberg, Germany). There was a significant correlation between exon 4 and intron 1 polymorphism (P = .041). Five cases (cases 3, 15, 16, 26, and 29) showed partial losses (i.e., both markers were informative, but only one of both showed LOH). Eleven cases exhibited LOH in both markers (Figure 2). Examples of single analyses are given in Figure 2. p53 Mutation Status In total, we found p53 mutations in 31 of 89 cases (34.8%) (Figure 3). There were 24 primary tumors (39.4%) and seven metastases (25%) with p53 mutations.

Table 3.

p53 Status of Tumors in Germline Heterozygous Arg/Pro Patients.

| Tumor Number | Exon 4 | p53 Mutation | |||

| p53-LOH | Arg/Pro | Exon | Codon | Amino Acid Exchange | |

| 1 | LOH | Arg | 4/42 | 1-bp insertion | Frameshift |

| 2 | LOH | Arg | 5/175 | CGC to CAC | Arg to His |

| 3 | LOH | Arg | 5/175 | CGC to CAC | Arg to His |

| 4 (M) | LOH | Arg | 5/175 | CGC to CAC | Arg to His |

| 5 (M) | LOH | Arg | 5/146 | 1-bp insertion | Frameshift |

| 6 | LOH | Arg | 5/135 | TGC to TAC | Cys to Tyr |

| 7 (M) | LOH | Arg | 8/306 | CGA to TGA | Arg to stop |

| 8 | LOH | Arg | 8/273 | CGT to TGT | Arg to Cys |

| 9 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 9A* (M) | LOH | Arg | 8/splice donor | G to T | Splicing |

| 10 | LOH | Arg | 8/273 | CGT to TGT | Arg to Cys |

| 11 | LOH | Arg | WT | ||

| 12 | LOH | Arg | WT | ||

| 13 | LOH | Arg | WT | ||

| 14 | LOH | Arg | WT | ||

| 15 | het | Arg/Pro | 5/175 | CGC to CAC | Arg to His |

| 16 | het | Arg/Pro | 7/splice acceptor | 12-bp deletion | Splicing |

| 17 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 18 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 19 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 20 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 21 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 22 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 23 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 24 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 25 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 26 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 27 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 28 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 29 | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 30 (M) | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 31 (M) | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 32 (M) | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

| 33 (M) | het | Arg/Pro | WT | ||

Primary tumor and metastasis were investigated; M—metastasis; het—heterozygous without LOH; WT—wild type.

Figure 2.

Allelic losses at the p53 locus, codon 72 genotype status, and p53 mutations in the 34 LOH-positive colorectal tumors and liver metastases.

Figure 3.

(A) Two peaks showing the heterozygous status Arg/Pro in the blood (NT) of patient 2; the corresponding tumor (T) shows only the 72Arg peak, confirming an LOH in this case (↓). (B) In accordance with this finding, sequencing analysis of tumor 2 detected the dominance of the mutant adenine allele (CGC to CAC) at codon 175.

p53-LOH and p53 Mutations p53-LOH occurred preferentially in tumors with p53 mutations (P = .029; Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between p53-LOH and p53 Mutations in Colorectal Tumors and Metastases.

Three p53 mutations were detected in cases where LOH could not be determined.

Correlation was calculated only in cases that were informative for LOH marker.

Arg/Pro Status Versus p53-LOH and p53 Mutations As there was a selective loss of the proline allele in cases of LOH, we assessed the mutational status of the retained arginine allele (Table 3, Figure 2). Examining the 33 germline heterozygous Arg/Pro patients (i.e., 34 tumors), we found that 10 of 14 cases (71.4%) with exon 4-LOH had p53 missense, frameshift, or splicing mutations, whereas such mutations occurred in only 2 of 20 cases (10%) without exon 4-LOH (Table 3). Interestingly, there was a predominance of mutations in codon 175, a common mutation hotspot codon in colorectal and head and neck cancers [25].

Considering all 89 tumors, p53 mutations were significantly correlated with the 72Arg tumor status (P < .001; Table 5). The seven tumors with germline homozygous Pro/Pro never showed p53 mutations.

Table 5.

Correlation between p53 Mutations and Arg/Pro Status in Colorectal Cancer and Metastases.

| p53 Mutations | Status at Codon 72 | ||

| Arg/Arg [n (%)] | Arg/Pro [n (%)] | Pro/Pro [n (%)] | |

| Primary tumors | 22/35 (63) | 2/20 (10) | 0/6 (0) |

| Metastases | 7/22 (31.6) | 0/5 (0) | 0/1 (0) |

| Total | 29/57 (50.9) | 2/25 (8) | 0/7 (0) |

| P < .001 | |||

Correlation of p53-LOH with Other Clinicopathologic Data There was a tendency for distal tumors to show a higher frequency of p53-LOH than did proximal tumors (43.7% for proximal vs 76.2% for distal tumors, P = .054). Allelic losses were not statistically correlated with sex, age, Dukes stage, and tumor grading (Table 2). In the six cases for which both the primary tumor and the corresponding liver metastases were available, the following observations were made: in one case, in contrast to the primary tumor, metastasis (A) showed an additional allelic loss (Table 3, tumor number 9/9A); in two cases, both primary tumor and metastases showed p53-LOH with p53 mutations (Figure 2, tumor numbers 34/34A and 35/35A); three cases were noninformative for the two polymorphic markers used without p53 mutations.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated p53-LOH frequency, p53 mutations, and p53 codon 72 polymorphism in a group of colorectal carcinomas and colorectal liver metastases. LOH frequency was similarly distributed (i.e., 62.1% in primary tumors and 63.2% in hepatic metastases); exon 4-LOH was associated only with loss of the 72Pro allele. The retained 72Arg was selectively mutated.

Although an association between codon 72 polymorphism and risk of cancer has been reported, the results with regard to colorectal carcinomas remain inconclusive [26,27]. Regarding blood, we did not observe a significant difference between colon cancer cases and ethnically matched controls for the distribution of codon 72 polymorphism. This may be caused by the relatively small number of cases in our study.

Considering tumor tissue DNA, we found a significantly higher frequency of the 72Arg in colorectal tumors. There was an apparent association of the Arg genotype with tumor progression, with metastases showing a bias toward the Arg genotype. There was only one metastasis with Pro/Pro homozygous constitution. This can be easily explained: all allelic losses at codon 72 of p53 exon 4 were directed toward the loss of the proline allele.

There are only a few studies reporting preferential retention of 72Arg in squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva [12], head and neck [15], and esophagus [28]. We suggest that the preferential loss of the 72Pro variant and/or mutations of 72Arg, also seen in our study for colorectal cancer and colorectal liver metastases, is of biologic significance. Thus, we tested all tumors for p53 mutations. Indeed, tumors that had retained the 72Arg allele often carried p53 mutations, with the “gain-of-function” type occurring with remarkably high frequency. In contrast, p53 mutations were found only in a small percentage of LOH-negative tumors in germline Arg/Pro patients and never in the germline homozygous Pro/Pro patients. A favored loss of the 72Pro, together with a selection for mutation in the retained 72Arg, was also reported by Brooks et al. [12] for squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva. Their data and ours seem to be consistent with reports on functionally significant interactions between some p53 mutants and the p53-related protein p73 in head and neck cancers [11].

It was reported that both forms of human p53 can increase the tumorigenicity of NIH 3T3 cells in nude mice and that 72Arg is more oncogenic in this respect than the 72Pro variant of p53 [29]. Thomas et al. [2] showed that the 72Arg form is a better inducer of transcription because of its stronger affinity for the TAFII32 and TAFII70 transcription factors. Therefore, the prevalence of the homozygous 72Arg variant in cervical cancer might be explained by the increased susceptibility of p53 to degradation by E6 protein of HPV16/18 [9]. Considering colorectal cancer and colorectal liver metastases, HPV infection must be excluded as a possible reason for the higher frequency of the homozygous 72Arg variant in the tumors. Otherwise, in a recent study, an enhanced apoptotic potential of the 72Arg variant caused by its preferential mitochondrial localization and its greater ubiquination by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2 was reported [30].

Based on our finding of a significant increase in the 72Arg variant with Dukes stage, we suggest that 72Arg correlates with the malignant potential of the tumor. This seems to be interesting because a similar increase in 72Arg status with more advanced cases has also been reported in urinary tract cancers [31] and lung cancer [14]. Furthermore, it is known that the development of hepatic metastases is largely dependent on certain risk factors, such as diet, and is modulated by different host factors or different colon subsites [32]. Although the number of cases investigated was low, we found in our group of primary tumors and metastases that the original location of metastasized tumors was always on the left (n = 2 sigmoid and n = 4 rectum)—the side of the highest carcinogenic exposure. Exposure to mutagens may first promote p53-LOH with preferential loss of the proline allele; secondly, the remaining Arg allele functions as a mediator responsible for a progressive genetic instability, leading to a more malignant potential, including the capability of invasiveness and metastasization. This is supported by Wynford-Thomas and Blaydes [33], who developed the theory that the genotype of the cell plays a major role in tumor progression and mainly determines the “choice” of further genetic events. Indeed, experiments have demonstrated that the ability of mutant p53 to bind p73, neutralize p73-induced apoptosis, and transform cells in cooperation with EJ-Ras was enhanced when codon 72 encoded Arg [11].

The percentage of p53-LOH in our series of colorectal cancers and liver metastases is in accordance with the data published in the literature [34]. We found a tendency for distal tumors to show allelic losses more frequently than proximal tumors. Our data are in line with Yashiro et al. [35], who found a higher frequency of p53-LOH in distal tumors without reaching significance in their small group of 28 colorectal cancers, so that the authors did not go into this finding. Eguchi et al. [19] confirmed a significantly higher frequency of p53 mutations in left-sided carcinomas than in right-sided carcinomas. We thus confirm the findings that proximal and distal colon carcinomas differ in their genetic mechanisms regulating initiation, morphologic variation, and/or progression [32,34,36,37]. The increased risk for genetic aberrations reflected as p53-LOH can be attributed to the fact that left-sided tumors come into contact with carcinogens more frequently. Here, bowel transit appears to produce a more prolonged aggression of the colon mucosa than in the right colon.

In summary, we found a preferential loss of the 72Pro allele and mutations in the retained 72Arg in colorectal cancer and liver metastases. When determining the risk for a specific cancer type, examinations of tumor tissue alone are problematic because allelic losses remain unmasked and are not considered. The increase in the frequency of p53-LOH, together with a higher frequency of 72Arg homozygotes in left-sided colon cancer, may be due to a high carcinogenic exposure in the distal part of the large intestines. Mutagens may selectively affect the proline allele, and LOH of the proline allele may be specifically advantageous for further tumor progression.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Hiltraud Scharfenort for her excellent technical help and to Bernd Wuesthoff for editing.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the Start-Up Research Program of the Medical Faculty of the Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg, Germany.

References

- 1.Levine AJ, Perry ME, Chang A, Silver A, Dittmer M, Welsh D. The 1993 Walter Huber Lecture: the role of the p53 tumour-suppressor gene in tumuorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:409–416. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas M, Kalita A, Labrecque S, Labrecque S, Pim D, Banks L, Matlashewski G. Two polymorphic variants of wild-type p53 differ biochemically and biologically. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1092–1100. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ara S, Lee PS, Hansen MF, Saya H. Codon 72 polymorphism of the TP53 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4961. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen WC, Tsai FJ, Wu JY, Wu HC, Lu HF, Li CW. Distributions of p53 codon 72 polymorphism in bladder cancer—proline form is prominent in invasive tumor. Urol Res. 2000;28:293–296. doi: 10.1007/s002400000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan R, Wu MT, Miller DP, Wain JC, Kelsey KT, Wiencke JK, Christiani DC. The p53 codon 72 polymorphism and lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9:1037–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Chen C, Chen SK, Chang YY, Chen CY. p53 codon 72 polymorphism in Taiwanese lung cancer patients: association with lung cancer susceptibility and prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu MW, Yang SY, Chiu YH, Chiang YC, Liaw YF, Chen CJ. A p53 genetic polymorphism as a modulator of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in relation to chronic liver disease, familial tendency, and cigarette smoking in hepatitis B carriers. Hepatology. 1999;29:697–702. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zehbe I, Voglino G, Wilander E, Delius H, Marongiu A, Edler L, Klimek F, Andersson S, Tommasino M. P53 codon 73 polymorphism and various human papillomavirus 16 E6 genotypes are risk factors for cervical cancer development. Cancer Res. 2001;61:608–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storey A, Thomas M, Kalita A, Harwood C, Gardiol D, Mantovani F, Breuer J, Leigh IM, Matlashewski G, Banks L. Role of a p53 polymorphism in the development of human papilloma virus-associated cancer. Nature. 1998;393:229. doi: 10.1038/30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanham S, Campbell L, Watt P, Gornall R. p53 polymorphism and risk of cervical cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1631. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marin MC, Jost CA, Brooks LA, Irwin MS, O'Nions J, Tidy JA, James N, McGregor JM, Harwood CA, Yulug IG, Vousden KH, Allday MJ, Gusterson B, Ikawa S, Hinds PW, Crook T, Kaelin WG. A common polymorphism acts as an intragenic modifier of mutant p53 behaviour. Nat Genet. 2000;25:47–54. doi: 10.1038/75586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks LA, Tidy JA, Gusterson B, Hiller L, O'Nions J, Gasco M, Marin MC, Farrell PJ, Kaelin WG, Crook T. Preferential retention of codon 72 arginine p53 in squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva occurs in cancers positive and negative for human papillomavirus. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6875–6877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tada M, Furuuchi K, Kaneda M, Matsumoto J, Takahashi M, Hirai A, Mitsumoto Y, Iggo RD, Moriuchi T. Inactivate the remaining p53 allele or the alternate p73? Preferential selection of the Arg72 polymorphism in cancers with recessive p53 mutants but not transdominant mutants. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:515–517. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papadakis ED, Soulitzis N, Spandidos DA. Association of p53 codon 72 polymorphism with advanced lung cancer: the Arg allele is preferentially retained in tumours arising in Arg/Pro germline heterozygotes. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1013–1018. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider-Stock R, Mawrin C, Motsch C, Boltze C, Peters B, Hartig R, Buhtz P, Giers A, Rohrbeck A, Freigang B, Roessner A. Retention of the arginine allele in codon 72 of the p53 gene correlates with poor apoptosis in head and neck cancer. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1233–1241. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergamashi D, Gasco M, Hiller L, Sullivan A, Syed N, Trigiante G, Yulug I, Merlano M, Numico G, Comino A, Attard M, Reelfs O, Gusterson B, Bell AK, Heath V, Tavassoli M, Farrell PJ, Smith P, Lu X, Crook T. P53 polymorphism influences response in cancer chemotherapy via modulation of p73-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:387–402. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forslund A, Lonnroth C, Andersson M, Brevinge H, Lundholm K. Mutations and allelic loss of p53 in primary tumor DNA from potentially cured patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2829–2836. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Wu TT, Catalano PJ, Ueki T, Satriano R, Haller DG, Benson AB, 3rd, Hamilton SR. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1196–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eguchi K, Yao T, Konomoto T, Hayashi K, Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M. Discordance of p53 mutations of synchronous colorectal carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:131–139. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clausen OPF, Lothe RA, Borresen-Dale AL, de Angelis P, Chen Y, Rognum TO, Meling GI. Association of p53 accumulation with TP53 mutations, loss of heterozygosity at 17p13, and DNA ploidy status in 273 colorectal carcinomas. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1998;7:215–223. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Aguilera JJ, Herrero MP, Maillo C, Moeno-Azcoita M, Fernandez N, Peralta AM. Loss of heterozygosity of TP53 is not correlated with clinico-pathological variables in sporadic colorectal carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1325–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual Cold. New York: Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budowle B, Chakraborty R, Giusti AM, Eisenberg AJ, Allen RC. Analysis of the variable number of tandem repeats locus D1S80 by the polymerase chain reaction followed by high resolution polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:137–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneider-Stock R, Ziegeler A, Haeckel C, Franke DS, Rys J, Roessner A. Prognostic relevance of p53 alterations and Mib-1 proliferation index in subgroups of primary liposarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2830–2835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hainault P, Hernandez T, Robinson A, Rodriguez-Tome P, Flores T, Hollstein M, Harris CC, Montesano R. IARC database of p53 gene mutations in human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation, revised formats and new visualisation tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;26:205–213. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sjalander A, Birgander R, Athlin L, Stenling R, Rutegard J, Beckman L, Beckman G. p53 germ line haplotypes associated with increased risk for colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:1461–1464. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.7.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang-Gohrke S, Becher H, Kreienberg R, Runnebaum IB, Chang-Claude J. Intron 3 16-bp duplication polymorphism of p53 is associated with increased risk for breast cancer by the age of 50 years. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:269–272. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawaguchi H, Ohno S, Araki K, Miyazaki M, Saeki H, Watanabe M, Tanaka S, Sugimachi K. p53 polymorphism in human papillomavirus-associated esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2753–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matlashewski G, Tuck S, Pim D, Lamb P, Schneider J, Crawford L. Primary structure polymorphism at amino acid residue. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:961–963. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.2.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumont P, Leu JI, Della Pietra AC, III, George DL, Murphy M. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Furihata M, Takeuchi T, Matsumoto M, Kurabayashi A, Ohtsuki Y, Terao N, Kuwahara M, Shuin T. p53 mutation arising in Arg72 allele in the tumorigenesis and development of carcinoma of the urinary tract. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1192–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindblom A. Different mechanisms in the tumorigenesis of proximal and distal colon cancers. Curr Opin Oncol. 2001;13:63–69. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynford-Thomas D, Blaydes J. The influence of cell context on the selection pressure for p53 mutation in human cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:29–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yashiro M, Carethers JM, Laghi L, Saito K, Slezak P, Jaramillo E, Rubio C, Koizumi K, Hirakawa K, Boland CR. Genetic pathways in the evolution of morphologically distinct colorectal neoplasms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2676–2683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mueller JD, Haegle N, Keller G, Mueller E, Saretzky G, Bethke B, Stolte M, Hoöfler H. Loss of heterozygosity and microsatellite instability in de novo versus ex-adenoma carcinomas of the colorectum. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1977–1984. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65711-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider-Stock R, Boltze C, Peters B, Hopfner T, Meyer F, Lippert H, Roessner A. Differences in loss of p16INK4 protein expression by promoter methylation between left- and right-sided primary colorectal carcinomas. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1009–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]