Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether family medicine residents graduating from rural programs assess themselves as more experienced and competent in a range of procedural skills than graduates of urban programs do.

DESIGN

Self-administered written survey.

SETTING

Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Residents from 5 Ontario family medicine programs in 2000 and 2001; a total of 535 surveys were available for analysis (response rate of 78%).

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Mean self-assessed experience and competence scores for 53 procedures at residency entry, end of year 1, and graduation.

RESULTS

Upon entry, there was no difference in mean procedural experience (2.89 vs 2.85, P = .54) or mean competence (2.34 vs 2.36, P = .88) scores between rural residents and their urban counterparts. There was a significant increase in procedural experience (P < .001) and competence (P < .001) scores during residency training. At graduation, mean experience (3.98 vs 3.70, P < .001) and competence (3.67 vs 3.39, P = .004) scores were significantly higher for rural residents than for their urban colleagues. A statistically larger proportion of residents graduating from rural programs assessed themselves as competent in 16 procedures. These included skills necessary for treating patients in emergency settings (establish intravenous lines for adults and infants, obtain arterial blood gas measurements, intubate adults and neonates, perform cautery for epistaxis, remove corneal foreign body, aspirate or inject knee and shoulder joints, and apply forearm or walking casts), for diagnostic procedures (endometrial biopsy and bone marrow aspiration), and for management of labour and delivery (vaginal delivery; vacuum extraction; and repair of first-, second-, and third-degree tears).

CONCLUSION

Graduates of rural programs who have had a substantial component of training in communities of fewer than 10 000 people report greater self-assessed experience and competence in procedural skills than graduates of urban programs do. The difference likely reflects the unique aspects of rural training sites, including preceptors’ competence in performing procedures.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Déterminer si les diplômés de la résidence en médecine familiale rurale considèrent qu’ils ont plus d’expérience et de compétences que ceux des programmes urbains en ce qui regarde diverses techniques cliniques.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête écrite auto-administrée.

CONTEXTE

Ontario.

PARTICIPANTS

Résidents de 5 programmes de médecine familiale ontariens en 2000 et 2001; un total de 535 enquêtes ont été utilisées pour l’analyse (taux de réponse: 78%).

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Scores moyens que les résidents s’attribuent concernant l’expérience et les compétences qu’ils ont relativement à 53 techniques, tel que mesuré au début de la résidence, après un an et à la fin du programme.

RÉSULTATS

Au début du programme, il n’y avait pas de différence entre les scores des résidents ruraux et urbains pour ce qui est de l’expérience (2,89 vs 2,85, P = 0,54) ou des compétences techniques (2,34 vs 2,36, P = 0,88). Une augmentation significative des scores d’expérience (P < 0,001) et de compétences (P < 0,001) s’est produite durant la résidence. À l’obtention du diplôme, les résidents ruraux avaient des scores moyens significativement plus élevés que leurs collègues urbains pour l’expérience (3,98 vs 3,70, P < 0,001) et les compétences (3,67 vs 3,39, P = 0,004). Un nombre significativement plus élevé de diplômés des programmes ruraux se jugeaient compétents dans 16 techniques. Cela comprenait les compétences requises pour traiter des patients des services d’urgence (installer un cathéter intraveineux chez un adulte et un nourrisson, effectuer la mesure des gaz artériels, intuber des adultes et des nouveaux-nés, faire une cautérisation pour une épistaxis, extraire un corps étranger cornéen, faire une infiltration ou une aspiration de liquide dans les articulations du genou et de l’épaule, et faire un plâtre de l’avant-bras ou un plâtre de marche), pour des techniques diagnostiques (biopsie de l’endomètre et aspiration de moelle osseuse), et pour la prise en charge du travail et de l’accouchement (accouchement vaginal; extraction par ventouse; réparation de déchirure des premier, deuxième et troisième degrés).

CONCLUSION

Les diplômés des programmes ruraux qui ont passé une partie substantielle de leur formation dans des collectivités de moins de 10 000 habitants considèrent qu’ils ont une expérience et des compétences techniques cliniques supérieures à celles des diplômés des programmes urbains. Cela résulte vraisemblablement des particularités propres aux sites de formation ruraux, incluant la compétence des enseignants dans l’exécution des techniques.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

This study compares self-assessed experience and competence in performing procedures between residents trained in rural programs and those trained in urban programs.

All residents from 2 rural and 3 urban programs were surveyed. Response rate was 78%.

At completion of their training, both rural and urban residents had increased their experience and competence; however, rural residents reported significantly more experience and competence than their urban counterparts did.

Male and female residents were equally influenced by the differences in rural versus urban training, although male residents, both rural and urban, reported higher levels of experience and competence.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Dans cette étude, l’évaluation que les diplômés des programmes ruraux font de leur expérience et de leurs compétences dans l’exécution de certaines techniques a été comparée à celle des résidents des programmes urbains.

L’enquête s’adressait aux résidents de 2 programmes ruraux et de 3 programmes urbains. Le taux de réponse était de 78%.

À la fin du programme, l’expérience et la compétence avaient augmenté chez les résidents ruraux comme chez les urbains; toutefois, les résidents ruraux rapportaient des augmentations considérablement plus fortes que leurs collègues urbains.

L’influence d’une formation rurale versus urbaine était présente autant chez les femmes que chez les hommes, quoique les hommes des 2 types de programmes rapportaient des niveaux d’expérience et de compétences plus élevés.

Family physicians require procedural skills to deliver high-quality medical services to their communities and must be competent in ambulatory and hospital procedures. Physicians in rural and remote areas perform more procedures than their urban colleagues.1-6

Attaining procedural skills requires training, development of competence, and a commitment to improve performance.7 Surveys of medical students show that many graduates have limited experience and confidence in basic and emergency procedures.8-14 Consequently, some residents begin postgraduate training without a solid foundation for mastering procedural skills.

Physicians completing internships,15 general practice training,16 family medicine residencies,16-19 and internal medicine residencies20 often begin their careers with a suboptimal set of procedural skills. Preliminary studies suggest that a component of rural training gives residents more confidence in their ability to apply their procedural skills.17,21

Ontario has a shortage of physicians in rural and remote communities. In 1991, 2 preceptor-based family practice residencies were established in rural communities in response to this shortage. Program goals include training physicians in rural settings and preparing them for practice in remote communities. Both programs are affiliated with an urban university but have unique resident selection processes, rotation schedules, and teaching sessions.22 A substantial portion of training occurs in communities of fewer than 10 000 inhabitants. Graduates successfully complete summative and licensing examinations23 and are more likely to practise in non-urban communities.24 Information on how rural preceptor-based training affects the actual skill set of graduates, however, is limited.

The primary goal was to determine whether family medicine residents graduating from rural programs assess themselves as more experienced and competent in a range of procedural skills than residents graduating from urban programs do. A secondary goal was to clarify whether rural programs select residents who are more experienced and competent with procedures.

METHODS

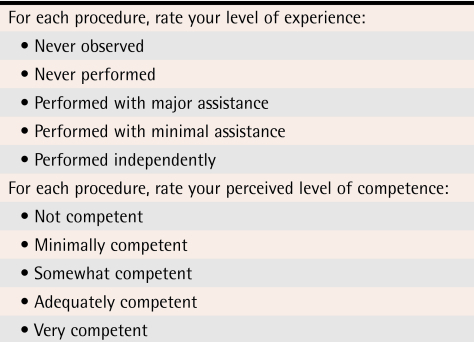

All family practice residents at 3 urban Ontario programs (McMaster University, University of Ottawa, and University of Western Ontario) and 2 rural programs (Family Medicine North and Northeastern Ontario) were approached to complete a written survey on procedures in June and July of 2000, 2001, and 2002. The sampling goal was a minimum of 50 residents, which would be sufficient to detect large differences with 80% power. Surveys were distributed at educational sessions with mailings using Dillman survey techniques to maximize the response rate. Demographic information included sex and graduating medical school. Participating residents anonymously reported their experience and competence in 53 procedures. A 5-point Likert scale for experience ranged from never observed to performed independently and for competence ranged from not competent to very competent (Table 1).

Table 1. Self-rated experience and competence in performing procedures.

Answers were dichotomized by combining the first 3 possible responses in one category and the last 2 possible responses in another category.

The survey was developed after reviewing the literature on procedures3,17,21,25-27; competence scales were adapted from previous studies.17,21 A group of family medicine educators with expertise in procedural skills reviewed the survey to ensure applicability to postgraduate training. Second-year family medicine residents pilot-tested the survey.

Completed surveys were coded to identify residents beginning programs (Entry R1), completing year 1 (Exit R1), and graduating (Exit R2). Data were entered into SPSS and examined using analysis of variance. Significance of differences in individual procedure scores upon graduation was further quantified by recoding self-assessed experience and competence into dichotomous variables: experienced versus not experienced and competent versus not competent (Table 1). Chi-square statistics were calculated for each procedure comparing rural and urban graduates. Ethics approval was received from the Lakehead University Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

A total of 268 of 345 (77.7%) residents completed surveys in 2000 and 267 of 342 (78.1%) in 2001, resulting in 535 surveys available for analysis. Response rate in rural programs (144/153 = 94.1%) was higher than in urban programs (391/534 = 73.2%). Because program personnel changes in 2002 made it difficult to collect an adequate number of surveys, 2002 results were not analyzed.

Mean experience and competence scores for groups of procedures were obtained for each procedure and by 12 body systems. A combined total score was calculated for all procedures. Analyses of variance comparing mean scores for each of the 12 grouped systems revealed no differences between years 2000 and 2001. Therefore, 2 years of data were combined resulting in 198 Entry R1, 169 Exit R1, and 168 Exit R2 surveys. Respondents included 299 women (61.9%) and 184 men (38.1%); 52 surveys did not indicate respondents’ sex. There was no difference between sexes for years 2000 and 2001.

Residents began programs with a mean procedural experience score of 2.86 (SD = 0.41) and a mean competence score of 2.35 (SD = 0.55). Total mean experience (P < .001) and competence scores (P < .001) along with mean experience and competence scores for each procedure increased significantly during residency. After 1 year of training, residents’ mean experience score was 3.36 (SD = 0.37) and competence score was 2.96 (SD = 0.47). Upon graduation, residents’ mean experience score was 3.77 (SD = 0.40) and competence score was 3.46 (SD = 0.53).

Most residents (68.7%) completed undergraduate training at Ontario medical schools. Upon beginning residency, graduates of Ontario medical schools had similar mean experience (P = .51) and competence scores (P = .84).

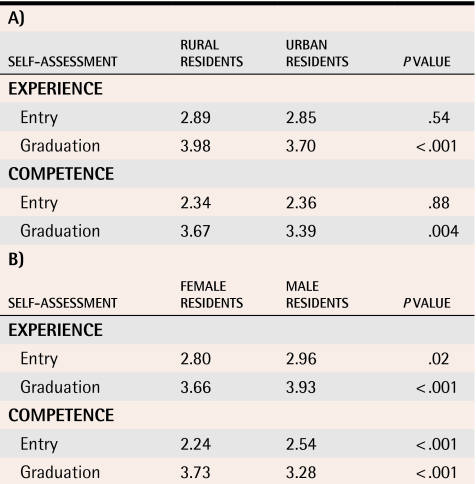

Upon starting residency, respondents from rural and urban programs had similar mean procedural experience and competence scores. After 2 years of training, rural residents assessed their mean procedural experience and competence significantly higher than their urban colleagues did (Table 2).

Table 2. Self-assessed procedural experience and competence.

Residents were compared on the basis of A) location and B) sex.

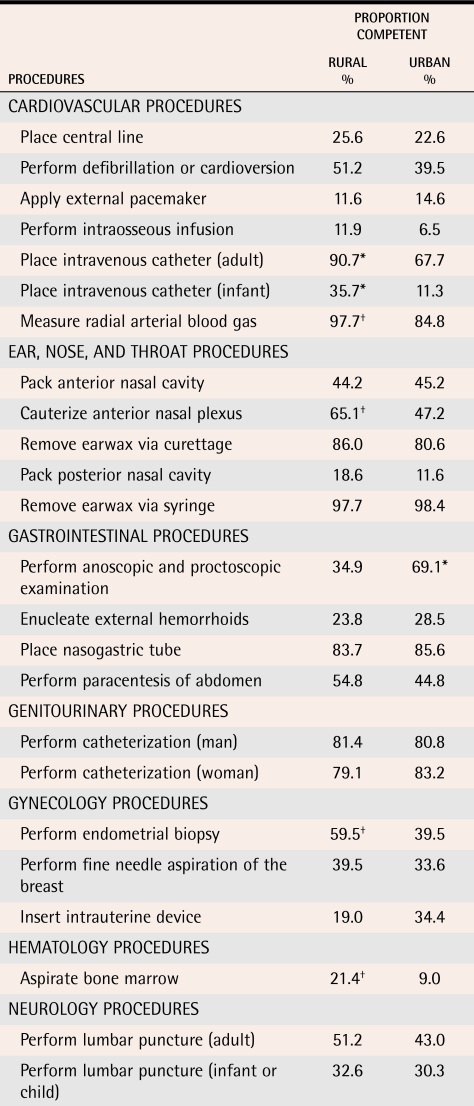

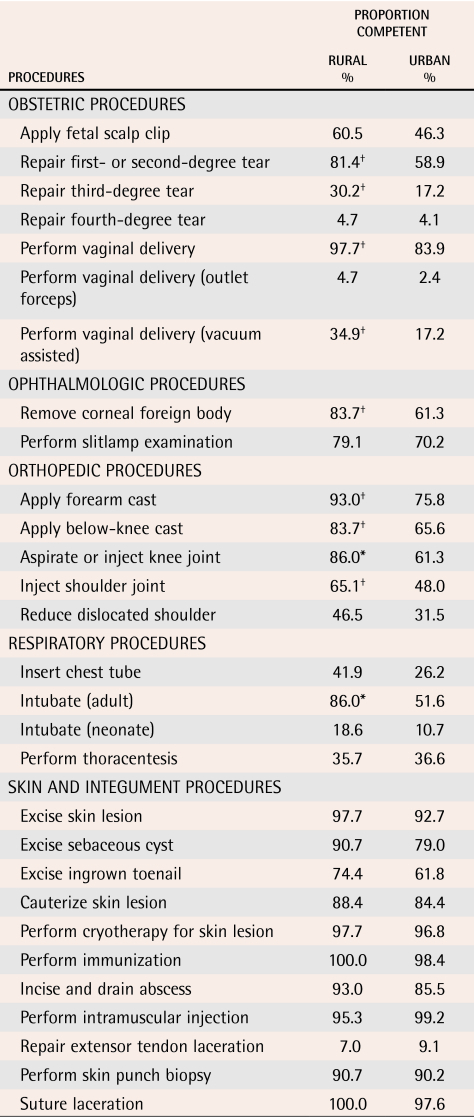

The proportion of rural graduates assessing themselves as competent in 16 procedures was significantly larger than the proportion of urban residents (Table 3). These procedures included skills necessary for treating patients in emergency departments, for performing diagnostic procedures, and for managing labour and delivery. For 12 of the 16 procedures, a significantly larger proportion of rural residents also assessed themselves as more experienced.

Table 3.

Procedural competence upon graduation between rural and urban programs

*Chi-square P < .005

†Chi-square P < .05.

Upon starting residency, men rated their experience and competence in performing procedures significantly higher than women rated themselves. Although experience and competence increased for all residents during residency, men rated their experience and competence significantly higher than women rated themselves upon graduation (Table 2). The interaction between sex and location for experience (P = .15) and competence (P = .36) along with the 3-way interaction between sex, time (from entry to graduation), and location for experience (P = .35) and competence (P = .33) were not statistically significant: men and women in rural and urban programs reported comparable rates of improvement in experience and competence during training.

DISCUSSION

Graduates of rural programs were more likely than graduates of urban programs to have performed procedural skills with minimal assistance and to have assessed themselves as competent. Differences in mean experience and competence scores have clinical significance because a significantly greater proportion of rural residents (12% to 34% of graduates) than urban residents assessed themselves as competent in 16 specific procedures (Table 3). This is important because graduates are more likely to perform procedures in practice when they receive appropriate training and to gain confidence during residency.18,25,28 Our results are consistent with previous comparisons (with a narrower range of procedural skills)17,21 showing that graduates from programs with rural components report greater competence and confidence in procedural skills.

Although it is possible that residents with an interest in procedural skills selected rural programs, medical students entered these family medicine residencies with similar self-assessed proficiency in performing procedures. These findings challenge researchers who have speculated that rural programs attract more medical students experienced in procedures.21

A specific curriculum for teaching procedural skills was not part of any of the programs during our study; consequently, residents’ opportunities to learn procedural skills might be greater in rural programs because of several related factors.22 In rural programs, family physicians are important role models and perform a variety of procedures. Performing specific procedures could make them more confident in their ability to teach procedures.20 Residents are more likely to be assigned responsibility during family practice rotations in emergency departments, hospital wards, or labour floors where procedural skills are important for diagnosis and treatment of various medical conditions. Needing a specific procedural skill to care for a patient is a strong motivator for learning that skill.29 Specialist physicians practising in rural regional centres support residents’ acquisition of skills because a substantial proportion of their referrals originate in outlying communities. Rural residents work one-on-one with family medicine and specialty preceptors, optimizing their acquisition of procedural skills. This differs from urban teaching hospitals where residents sometimes compete for opportunities to perform procedures and are typically taught by senior residents who could be less experienced than practising physicians.

Male residents’ rating their experience and competence higher upon residency entry and completion is consistent with researchers’ observations that practising male physicians generally perform more procedures.3,4 Although the reasons for these differences are unclear, professional culture and socialization is believed to have a role.

The parallel increase in experience and competence scores during training is supported by research suggesting that development of competence is related to actual experience in a procedure. Fincher and Lewis12 demonstrated a relationship between frequency of performing procedures and self-assessed competence, Taylor11 demonstrated an association between frequency and perceived proficiency, and Hicks and associates30 noted an association between frequency of performing procedures and comfort level.

Because residents were not assessed independently on their performance of procedural skills, which procedures they were able to perform independently upon graduation cannot be ascertained. Although self-assessed experience or competency scores might be over-reported or underreported, a progression for all procedures during residency gives confidence that differences upon graduation are relevant. Self-assessment of a procedural skill is useful, as it reflects residents’ views of their ability to perform and confidence in performing the procedure. Bandura31 advocates the principle of self-efficacy, which is an individual’s judgment of his or her capabilities to perform a particular skill successfully. Psychomotor researchers have provided evidence of a significant relationship between self-efficacy and actual skill performance.32,33

One strength of this study is response rates of 94% in rural and 73% in urban programs. The high response in rural programs assures a true reflection. The lower response rate in urban programs could have undersampled residents with limited interest in procedures, thus minimizing actual differences. As this study is limited to Ontario residents, it might not be generalizable to other family medicine residency programs. These findings should be examined within the context of the teaching environment.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that graduates of rural programs with a substantial component of training in communities with fewer than 10 000 persons assess themselves as more experienced and competent than graduates of urban programs do in a range of procedural skills. These differences likely reflect the unique aspects of rural training sites, including the procedural competence of preceptors.

Acknowledgments

I thank many physician colleagues for their contributions with special recognition to Dr John Jamieson for statistical assistance and Dr Len Kelly for manuscript review. This study was made possible by the participation of family medicine residents and the administrative support at their respective programs. This work was supported by an AMS/Wilson Senior Fellowship from Associated Medical Services, Incorporated.

Biography

Dr Goertzen is an Associate Clinical Professor at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont, and is an Associate Professor of Family Medicine at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine in Thunder Bay, Ont.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Baldwin LM, Hart LG, West PA, Norris TE, Gore E, Schneeweiss R. Two decades of experience in the University of Washington family medicine residency network: practice differences between graduates in rural and urban locations. J Rural Health. 1995;11(1):60–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1995.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt H, Miles DA, Bridges-Webb C, Neary S, Charles J, Traynor V. A comparison of country and metropolitan general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 1994;23(6):1116–1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaytors RG, Szafran O, Crutcher A. Rural-urban and gender differences in procedures performed by family practice residency graduates. Fam Med. 2001;33:766–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eliason BC, Lofton SA, Mark DH. Influence of demographics and profitability on physician selection of family practice procedures. J Fam Pract. 1994;39(4):341–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutten-Czapski P, Pitblado R, Slade S. Short report: scope of family practice in rural and urban settings. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:1548–1550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wetmore SJ, Agbayani R, Bass MJ. Procedures in ambulatory care: which family physicians do what in southwestern Ontario? Can Fam Physician. 1998;44:521–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts RW. The GP proceduralist. Aust Fam Physician. 1993;22(8):1475–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.House AK, House J. Improving basic surgical skills for final year medical students: the value of a rural weekend. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:344–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2000.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunskaar S, Seim SH. Medical students’ experiences in medical emergency procedures upon qualification. Med Educ. 1985;19:294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1985.tb01324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spike NA, Veitch PC. Competency of medical students in general practice procedural skills. Aust Fam Physician. 1991;20(5):586–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor DM. Undergraduate procedural skills training in Victoria: is it adequate? Med J Aust. 1997;166:251–254. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fincher RME, Lewis LA. Learning, experience, and self-assessment of competence of third-year medical students in performing bedside procedures. Acad Med. 1994;69:291–295. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank S, Rabinovich S. Practical procedures in internal medicine: a workshop for fourth-year medical students. J Med Educ. 1983;58:784–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly MH, Campbell LM, Murray TS. Clinical skills assessment. Br Med J Gen Pract. 1999;49:447–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spike NA, Veitch PC. General practice procedural skills. Aust Fam Physician. 1991;20(9):1312–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sturmberg JP. Procedural skills in general practice: are we going to lose this facet of general practice care? Aust Fam Physician. 1999;28(12):1211–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon-Warren N. Competency scores of common procedural skills as self-reported by graduating family medicine residents in Ontario. North Ont Med Program News. 1997;Dec:3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor HM, Davidson JR. Emergency medicine skills. Are primary care physicians adequately prepared? Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:1789–1793. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speechley M, Weston WW, Dickie GL, Orr V. Self-assessed competence: before and after residency. Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:459–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wickstrom GC, Kolar MM, Keyserling TC, Kelley DK, Xie SX, Bognar BA, et al. Confidence of graduating internal medicine residents to perform ambulatory procedures. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:361–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wetmore SJ, Stewart M. Is there a link between confidence in procedural skills and choice of practice location? Can J Rural Med. 2001;6(3):189–184. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goertzen J. Making rural docs in northwestern Ontario (FMN: NWO Program). Can J Rural Med. 2002;7(3):217–218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKendry RJ, Busing N, Dauphinee DW, Brailovsky CA, Boulais AP. Does the site of postgraduate training predict performance on summative examinations? A comparison of urban and remote programs. CMAJ. 2000;163(6):708–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutten-Czapski P, Thurber AD. Who makes Canada’s rural doctors? Can J Rural Med. 2002;7(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Turk M, Susman J. Perceived core procedural skills for Nebraska family physicians. Fam Pract Res J. 1992;12(3):297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Goes T, Grzybowski SC, Thommasen H. Procedural skills training. Canadian family practice residency programs. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:78–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson N, Grzybowski S, Thommasen C, Berkowitz J, Thommasen H. Procedural skills practiced by British Columbia family physicians. Can J Rural Med. 2001;6(3):179–185. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pringle M, Hasler J, Marco PD. Training for minor surgery in general practice during preregistration surgical posts. BMJ. 1991;302:830–832. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6780.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturmberg J. Learning relevant procedural skills: are supervisors providing opportunities? Aust Fam Physician. 1997;26(10):1163–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hicks CM, Gonzales R, Morton MT, Givvons RV, Wigton RS, Anderson RJ. Procedural experience and comfort level in internal medicine trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:716–722. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moritz SE, Feltz DL, Fahrbach KR, Mack DE. The relation of self-efficacy measures to sport performance: a meta-analytic review. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(3):280–294. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2000.10608908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang TS, Schwartz JL, Karimipour DJ, Orringer JS, Hamilton T, Johnson TM. An education theory-based method to teach a procedural skill. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1347–1361. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.11.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]