Abstract

Telomerase, the enzyme that elongates telomeres, is essential to maintain telomere length and to immortalize most cancer cells. However, little is known about the regulation of this enzyme in higher eukaryotes. We previously described a domain in the hTERT telomerase catalytic subunit that is essential for telomere elongation and cell immortalization in vivo but dispensable for catalytic activity in vitro. Here, we show that fusions of hTERT containing different mutations in this domain to the telomere binding protein hTRF2 redirected the mutated hTERT to telomeres and rescued its in vivo functions. We suggest that this domain posttranscriptionally regulates telomerase function by targeting the enzyme to telomeres.

Complete replication of the eukaryotic genome requires the de novo addition of telomeric DNA to the ends of chromosomes. In almost all cases, this is accomplished by the telomerase reverse transcriptase (23). Unlike in most eukaryotes tested to date, telomerase activity is generally absent in most human somatic cells, leading to a progressive loss of telomeric DNA that ultimately triggers a proliferative checkpoint, resulting in a senescence growth arrest. Even if this checkpoint is overridden, for example, by the disrupting p53 or pRb pathway, the loss of telomeric DNA is eventually lethal, leading to a state called crisis (25). Cancer cells overcome the proliferative blockade imposed by telomere shortening primarily through the improper activation of telomerase (27). Inhibition of the catalytic subunit of telomerase by the expression of a dominant-negative version of the protein has been found to greatly impede, if not abolish, human tumor cell growth in vivo (13, 15). Understanding how telomerase functions and how it is regulated may therefore aid in developing strategies to therapeutically inhibit this enzyme for the treatment of human cancer.

Human telomerase is minimally composed of two subunits: the hTERT reverse transcriptase protein and the hTR RNA (23). Although these two components can reconstitute telomerase catalytic activity in vitro (31), mounting evidence argues that they are not sufficient for telomere elongation in vivo. For example, while telomerase enzyme activity can be detected at all stages of the cell cycle in a variety of dividing immortal cells (16), telomere replication occurs only in S phase (32). Moreover, the addition of a double hemagglutinin epitope tag to the C terminus of hTERT leaves the protein catalytically active but unable to elongate telomeres in vivo (6, 24, 34).

A region called the DAT (for dissociates activities of telomerase) domain in the N terminus of the human catalytic subunit that is necessary for in vivo telomere elongation was recently mapped (1). Like the addition of a hemagglutinin epitope tag, mutations in the DAT domain have no affect on the ability of hTERT to restore telomerase activity when introduced into telomerase-negative cells but abolish the ability of the enzyme to maintain telomere length and to immortalize cells. Since mutations in this domain do not perturb the nuclear localization of hTERT (1), the DAT domain presumably is involved in some step of telomere elongation once a catalytically functional enzyme is assembled in the nucleus. Human cells expressing the DAT mutant of hTERT have a phenotype reminiscent of those of yeast strains with mutations in the gene EST1, EST3, or CDC13. While mutations in any of these three genes have no affect on in vitro telomerase activity, they do cause telomere shortening and eventually a decrease in cell proliferation (19-21). Est1p and Est3p associate with the telomerase enzyme directly, whereas Cdc13p is a single-stranded telomeric DNA binding protein that interacts with telomerase indirectly via Est1p, potentially recruiting telomerase to telomeres (3, 9). Indeed, Evans and Lundblad demonstrated that direct fusion of Cdc13p to the telomerase catalytic subunit greatly increases telomere length and overcomes the telomere shortening observed in yeast lacking the EST1 gene (8). We therefore reasoned that if the DAT domain is involved in telomere recruitment, mutations in the domain may be rescued by targeting the mutant hTERT to the telomeres by fusion with a telomere binding protein.

In humans, hTRF1, hTRF2, and hPot1 are known to bind directly to telomeric DNA (3). Of these, hTRF2 and hPot1 are known to bind near or directly to single-stranded telomeric DNA (2, 12), the substrate of telomerase. We therefore fused wild-type hTERT or hTERT containing different mutations in the DAT domain to hTRF2 and found that the fusion did not interfere with the catalytic activity of telomerase but promoted the association of hTERT with telomeres. Consequently, hTRF2 fusion to wild-type hTERT caused progressive telomere elongation. Importantly, the inability of hTERT proteins to maintain telomeres in vivo and to immortalize human cells when hampered by a variety of mutations in the DAT domain was rescued by this telomere-targeting approach. These results suggest that the DAT domain functions to negotiate telomerase-telomere interactions, which in turn could be a mechanism to regulate telomere length.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs.

A PCR cloning approach was used to introduce an EcoRI restriction site 5′ of the myc-hTRF2 cDNA and to replace the stop codon with an EcoRI site. The resultant fragment was cloned into the EcoRI site of pBabe(puro or hygro)-flag-hTERT and -hTERT+128 (1), creating the plasmids pBabe(puro or hygro)-myc-hTRF2-flag-hTERT and -hTERT+128. Similarly, the same fragment was cloned into pEYFP-N1 (Clontech) using HindIII-BamHI sites, making pEYFP-N1-myc-hTRF2. This plasmid was also digested with BglII-BamHI to excise the entire myc-hTRF2-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) open reading frame, which was subcloned into the BamHI site of pBabehygro, yielding the plasmid pBabehygro-myc-hTRF2-YFP. To make pBabehygro-myc-hTRF2, hTRF2 cDNA PCR amplified to contain flanking EcoRI sites was cloned into the EcoRI site of pBabehygro. pBabehygro-YFP was made by inserting the blunted NheI-SspI YFP fragment from pEYFP-N1 into blunted sites of pBabehygro. T+128DALR was changed to AAALA, N+125TV was changed to NAA, and S+134GA was changed to NAA in hTERT using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) to create pBabepuro-flag-hTERT+128-3A, pBabepuro-flag-hTERT+125NAA,and pBabepuro-flag-hTERT+134NAA, respectively, exactly as previously described (1). pBabepuro-myc-hTRF2DPV-flag-hTERT and -hTERT+128 were created by first introducing EcoRI sites 5′ of the myc-hTRF2 cDNA and in place of the stop codon by PCR. The mutations V52D, N53P, and R492V were then introduced into this sequence using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis, after which the resultant hTRF2DPV cDNA was sequenced to confirm the mutations and introduced into the EcoRI site of pBabepuro-flag-hTERT or -hTERT+128. phTRF1-pS65T-C1 was created by subcloning the cDNA (GenBank accession number U40705) of hTRF1 into ps65T-C1 (Clontech), resulting in an N-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion.

Cell culture and immortalization.

LM217 cells or the simian virus 40 early region-transformed human embryonic kidney cell line HA5 (28) at population doubling (pd) 51 were infected as previously outlined (1) with amphotropic retrovirus derived from the above-mentioned pBabe constructs. Stably infected polyclonal populations were selected in medium supplemented with either 0.5 to 1.0 μg of puromycin or 100 to 300 μg of hygromycin-B (Sigma)/ml; pd 0 was arbitrarily assigned to the first confluent plate under selection. For coexpression studies, HA5 cells expressing hTERT or hTERT+128 at pd 2 were again infected with the described constructs and selected in media supplemented with 100 μg of hygromycin-B/ml. HA5 cells were continually passaged at 1:8 under selection until crisis or until the culture divided 2.5 times more than vector control cell lines. Crisis was defined as the period when cultures failed to become confluent within 3 weeks and displayed massive cell death.

Protein expression.

Soluble lysate (150 μg) from either the LM217 or HA5 stable cell line was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted as previously described (1) with the primary mouse monoclonal antibody anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma), anti-cmyc (9E10), or anti-actin (C-2) or the rabbit anti-GFP (FL) polyclonal antibody (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) to detect flag-hTERT, myc-TRF2, actin, or YFP, respectively, followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase (81-6520) or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase (81-6120) (Zymed Laboratories Inc.). Proteins were detected with ECL reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Localization of the myc-hTRF2 and myc-hTRF2-flag-hTERT fusion proteins (both wild-type and mutant forms) was visualized by indirect immunofluorescence in LM217 cell lines stably expressing these proteins. Plasmid phTRF1-pS65T-C1 encoding GFP-hTRF1 was transiently transfected into these LM217 cell lines by FuGENE 6 (Roche) following the manufacturer's directions. The cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 1× phosphate-buffered saline- 0.5% NP-40, and blocked with PBG (1× phosphate-buffered saline, 0.2% cold fish gelatin, 0.5% bovine serum albumin). myc-hTRF2 was detected by the 9E10 anti-cmyc antibody recognized by a donkey anti-mouse antibody conjugated with rhodamine (tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate; Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in PBG. GFP-hTRF1 was visualized by virtue of its fluorescence. Nuclei were stained with 0.5 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma)/ml. YFP-hTERT (7), hTRF2-YFP, and hTRF2DPV-YFP were transiently expressed in LM217 cells as described above and visualized by virtue of their fluorescence. Cells were examined at ×630 magnification on a Zeiss LSM-410 confocal fluorescent microscope.

Detection of in vitro telomerase activity, hTERT mRNA, and telomeres.

Lysates (0.2 μg) prepared from infected HA5 cells at pd 1 and 2 were assayed for telomerase activity using the telomeric repeat amplification protocol. As a negative control, duplicate reactions were heat treated at 85°C for 2 min to inactivate the telomerase. The reaction products were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gels, dried, and exposed to a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) screen to visualize enzyme activity as previously described (18).

Total RNA isolated from infected HA5 cells using the RNazol reagent (Teltest) was amplified using semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR with primers specific for endogenous hTERT, ectopic hTERT, or GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), after which the reaction products were resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gels and visualized by exposure to a PhosphorImager screen as previously described (14).

Genomic DNA (5 μg) isolated from HA5 cells was digested with HinfI and RsaI restriction enzymes to release terminal restriction fragments containing telomeric DNA, Southern hybridized with a 32P-labeled telomeric (C3TA2)3 oligonucleotide, and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen, similar to methods previously described (6).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Redistribution of hTERT to telomeres by fusion to hTRF2.

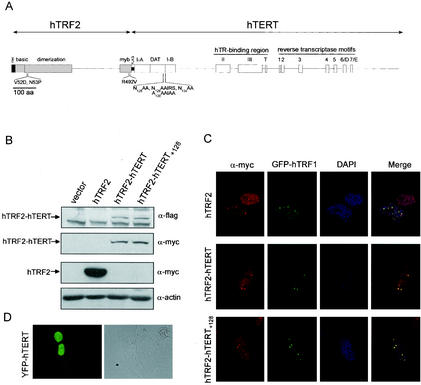

Since hTERT is found throughout the nucleus (7, 26), precluding detailed analysis of the protein bound to telomeres, we investigated whether the DAT domain of hTERT is involved in the recruitment of telomerase to telomeres by specifically targeting the mutated protein to telomeres through fusion with hTRF2, an approach that has proven valuable in dissecting the recruitment of telomerase to telomeres in yeast (8). hTRF2 binds to double-stranded telomeric DNA (4) and is positioned at the site of single-stranded DNA invasion into double-stranded telomeric DNA in the higher-order t-loop complex (12). Therefore, hTRF2 not only resides on telomeres but binds at a site near single-stranded DNA, the substrate of telomerase. We fused an N-terminal myc epitope-tagged hTRF2 in frame to the N terminus of flag epitope-tagged hTERT containing a T128DALRG-to-NAAIRS substitution in the DAT domain (hTERT+128) to produce the fusion protein hTRF2-hTERT+128 (Fig. 1A). As a positive control, a similar fusion was also made between hTRF2 and wild-type hTERT, generating the protein hTRF2-hTERT.

FIG. 1.

Fusion of hTERT to hTRF2 relocalizes hTERT to telomeres. (A) Scale diagram of the protein structure of hTRF2-hTERT fusion. The positions of epitope tags and substitution mutations generated in hTRF2 and hTERT are indicated. (B) Stable expression of hTRF2 and hTRF2 fusion proteins in LM217 cells. Lysates isolated from LM217 cells expressing the described constructs were immunoblotted with anti-flag (α-flag) and anti-myc antibodies to detect ectopic hTERT and hTRF2, respectively. Actin served as a loading control. (C) Fusion of hTRF2 targets hTERT to telomeres. Telomeric localization of hTRF2, hTRF2-hTERT, and hTRF2-hTERT+128 proteins visualized by indirect immunofluorescence with an anti-myc antibody and colocalization with transfected GFP-hTRF1 in LM217 cells. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. (D) Diffuse nuclear distribution of hTERT. An example of LM217 cells transiently expressing YFP-hTERT is shown as a phase-contrast image (right) to visualize the cells and as a fluorescent image (left) to visualize the YFP-tagged protein.

To determine if the described fusions relocalize hTERT, human LM217 cells were stably infected with retroviruses encoding hTRF2-hTERT, hTRF2-hTERT+128, or, as a control, hTRF2. LM217 cells are immortal transformed human fibroblasts that have long telomeres (22), which greatly facilitates the visualization of proteins bound to telomeres (4, 5). We first confirmed expression of these fusion proteins. Immunoblot analysis with an anti-myc antibody revealed an ∼70-kDa protein corresponding to hTRF2 in LM217 cells stably infected with an hTRF2 retrovirus. An ∼185-kDa protein corresponding to the predicted size of hTRF2-hTERT or hTRF2-hTERT+128 was also detected using both anti-myc (to hTRF2) and anti-flag (to hTERT) antibodies in cells infected with retroviruses encoding these fusion proteins (Fig. 1B). We next monitored the subcellular distributions of the proteins. As anticipated, expressed hTRF2 formed a punctate speckled pattern in interphase cells, as detected by indirect immunofluorescence using an anti-myc antibody (Fig. 1C). We verified that these sites colocalized with another telomeric binding protein, hTRF1 (5), either by indirect immunofluorescence with an anti-hTRF1 antibody (not shown) or by ectopically expressing GFP-tagged hTRF1 (Fig. 1C). Importantly, fusion of hTRF2 with either wild-type hTERT or hTERT+128 redistributed hTERT from general nuclear staining (Fig. 1D) to nuclear speckles that colocalized with both GFP-hTRF1 and endogenous hTRF1 (Fig. 1C and not shown), indicating that the hTRF2-hTERT proteins are at telomeres.

hTERT retains telomerase catalytic activity when fused to hTRF2.

We next addressed in HA5 cells whether the catalytic activity of telomerase is perturbed by the addition of the large hTRF2 protein to the N terminus of hTERT. HA5 cells are human embryonic kidney cells, transformed with the early region of simian virus 40, that lack hTERT but express the RNA subunit of telomerase (6). These cells therefore provide a system to assay hTERT function, since ectopic expression of wild-type hTERT restores telomerase catalytic activity (1). Vectors encoding no transgene, hTERT, hTERT+128, or hTRF2 fused to wild-type or +128 DAT mutant hTERT were introduced into HA5 cells, and ectopic protein expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2A).

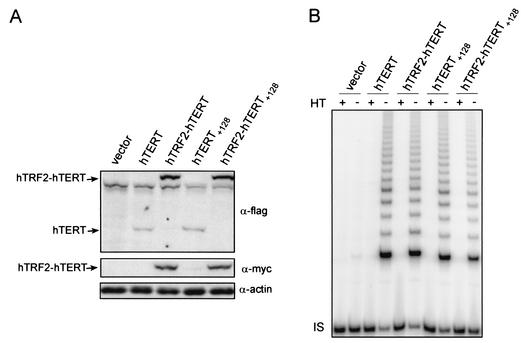

FIG. 2.

hTRF2-hTERT fusion proteins retain in vitro telomerase activity. (A) Stable expression of hTRF2 and hTRF2-hTERT in HA5 cells. Lysates isolated from HA5 cells expressing the described constructs were immunoblotted with anti-flag (α-flag) and anti-myc antibodies to detect ectopic hTERT and hTRF2, respectively. Actin served as a loading control. (B) Fusion of hTRF2 to hTERT does not affect telomerase activity. Extracts isolated from HA5 cells stably expressing the described proteins were assayed for in vitro telomerase activity. As a negative control, duplicate lysates were heat treated (+HT) to inactivate telomerase prior to the assay. The internal standard (IS) served as a positive control for PCR amplification.

We next assayed whether extracts from these cells could elongate a telomeric primer in vitro, which when resolved results in a ladder of telomerase-elongated products (18). As controls, extracts prepared from HA5 cells containing the vector alone were shown to lack detectable telomerase activity whereas the same cells expressing wild-type hTERT had high levels of activity (Fig. 2B). Importantly, extracts from cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT contained levels of activity similar to those of cells expressing wild-type hTERT. As previously described (1), HA5 cells containing hTERT+128 also had levels of in vitro catalytic activity equal to those of cells expressing wild-type hTERT (Fig. 2B). And as was the case with fusion of wild-type hTERT, fusion of hTRF2 to hTERT+128 did not greatly alter the amount of catalytic activity (Fig. 2B). Thus, the physical tethering of hTRF2 to either wild-type or mutant hTERT did not perturb the catalytic activity of hTERT.

Fusion of hTRF2 to hTERT causes elongation of telomeres in vivo.

Because telomere shortening and crisis can be averted in HA5 cells by ectopic expression of wild-type hTERT (1), these cells also provide a system to determine if the fusion of hTRF2 could rescue the in vivo functions of hTERT containing a mutation in the DAT domain. To begin this analysis, we first monitored telomere length and cell life span in control cells. Genomic DNA from control vector-infected HA5 cells or HA5 cells expressing wild-type hTERT or hTRF2-hTERT at increasing pds was digested with restriction enzymes to liberate telomere-containing fragments, which were detected by Southern hybridization with a telomere-specific probe. Immortalization was ascertained by determining if the cells could proliferate at least twice as long as the vector control cells. As expected, expression of hTERT stabilized telomere length in the HA5 cells and led to their immortalization whereas control HA5 cells underwent telomere shortening and were mortal (Fig. 3). Cells stably infected with hTRF2 also exhibited telomere shortening and entered crisis like vector control cells (not shown). Like wild-type hTERT, expression of hTRF2-hTERT immortalized HA5 cells (Fig. 3B). Thus, hTRF2-hTERT retained the in vitro and in vivo properties of wild-type hTERT.

FIG. 3.

In vivo function of hTERT+128 is rescued by fusion with hTRF2. (A) hTRF2-hTERT+128 arrests telomere shortening. Restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA isolated from late-passage HA5 cells expressing hTERT, hTRF2-hTERT, or hTRF2-hTERT+128 (left) or from HA5 cells at the time of infection or once a vector control population was selected (right) were hybridized with a telomeric probe to visualize telomere-containing fragments. Molecular size markers are shown on the left. (B) hTRF2-hTERT+128 can immortalize human cells. The life spans of HA5 cell lines infected with vectors expressing hTRF2-hTERT (□) or hTRF2-hTERT+128 (○) or controls infected with vector alone (▴) or expressing hTERT (▪) or hTERT+128 (•) are plotted against time.

Intriguingly, whereas HA5 cells expressing hTERT stabilized telomeres at an average length of ∼4.5 kb, those with hTRF2-hTERT progressively elongated their telomeres to lengths of >10 kb (Fig. 3A). These data suggest not only that fusion of hTRF2 to hTERT was capable of redirecting hTERT to telomeres but that relocalization greatly enhanced the ability of telomerase to elongate telomeres. By artificially localizing telomerase to telomeres, the normal control of telomere length is overridden, arguing that recruitment of telomerase to telomeres is a regulated event that may help, in part, to regulate telomere length.

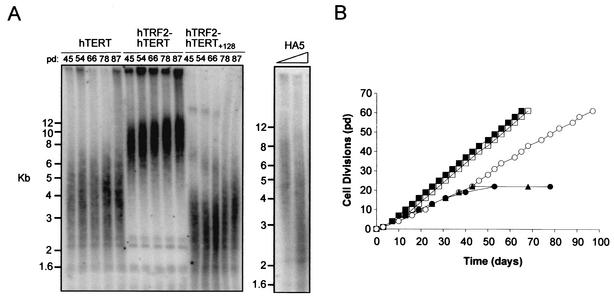

hTERT DAT domain mutants are rescued by fusion to hTRF2.

To test if the DAT domain is involved in telomere localization, we monitored telomere length and cell life span in HA5 cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128. Consistent with hTRF2 targeting this mutant to telomeres where the functional catalytic domain could elongate them, we find that the telomere-shortening characteristic of the hTERT+128 mutant was arrested when this crippled hTERT molecule was fused to hTRF2 (Fig. 3A). As previously demonstrated, HA5 cells expressing hTERT+128 failed to immortalize and instead underwent crisis, as did telomerase-negative vector control cells (Fig. 3B). In sharp contrast, cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128 were able to proliferate well beyond the time hTERT+128-expressing cells entered crisis (Fig. 3B). Additional mutants were also created (Fig. 1A) at the +128 position (hTERT+128-3A, in which T+128, D+129, and R+132 were mutated to alanine) or other regions of the DAT domain (hTERT+125NAA, in which N+125TV was changed to NAA, and hTERT+134NAA, in which S+134GA was changed to NAA). These hTERT mutants, either alone or fused to hTRF2, were stably expressed in HA5 cells and found to restore high levels of telomerase activity, confirming that neither the mutation nor the fusion disrupted catalytic activity (Fig. 4A). Again, cells expressing hTERT+128-3A, hTERT+125NAA, or hTERT+134NAA entered crisis, whereas like the positive-control hTRF2-hTERT-expressing cells, cells expressing these mutants fused to hTRF2 proliferated beyond vector control cells (Fig. 4B). Therefore, delivery of catalytically active DAT domain mutants of hTERT to telomeres by fusion with hTRF2 restores telomerase function to the cell, permitting extended proliferation.

FIG. 4.

In vivo functions of other hTERT DAT mutants are rescued by fusion with hTRF2. (A) Telomerase activities of other DAT mutants of hTERT alone or fused to hTRF2. Extracts isolated from HA5 cells stably expressing the described proteins were assayed for in vitro telomerase activity. The internal standard (IS) served as a positive control for PCR amplification. (B) Fusion of hTRF2 to other DAT mutants can immortalize human cells. The life spans of HA5 cell lines expressing hTERT+128-3A (▪), hTRF2-hTERT+128-3A (□), hTERT+125NAA (•), hTRF2-hTERT+125NAA (○), hTERT+134NAA (▴), hTRF2-hTERT+134NAA (▵), vector (♦), or hTRF2-hTERT (⋄) are plotted against time.

We note that the growth of cells expressing hTRF2 fused to the DAT domain mutants was slower and the telomere length was less than that of cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT (Fig. 3 and 4B). One explanation for this difference is that since hTRF2 does not bind to the very end of telomeres (12), the fusion proteins of hTRF2 with hTERT DAT mutants may be inefficient at elongating telomeres, occasionally resulting in critically short telomeres that lead to cell death. Alternatively, fusion with hTRF2 may fail to complement other defects associated with mutating the DAT domain, occasionally resulting in suboptimal telomere lengths. Nevertheless, the rescue of the four different DAT mutants of hTERT by fusion to a telomere binding protein argues that the DAT domain plays a crucial role in hTERT function, which is to facilitate the interaction of telomerase with telomeres.

The DNA binding activity of hTRF2 is required to rescue the in vivo function of an hTERT DAT mutant.

To confirm that targeting of hTERT DAT mutants to telomeres rescued their functions, we addressed whether an hTRF2 protein defective in telomere binding fused to hTERT+128 would fail to immortalize human cells. To create an hTRF2 mutated protein with as little disruption as possible, we generated a mutant of hTRF2 modeled after substitution mutations introduced into TRF1 to disrupt specific functions, based on the crystal structure of the protein (10). We first mutated the myb-like DNA-binding domain of hTRF2 with a single substitution of R492V. While the same mutation in TRF1 (R425V) is known to impede telomeric binding (10), loss of telomeric binding in hTRF2 creates a potent dominant-negative protein that, through heterodimerization with endogenous hTRF2, leads to rapid growth arrest or cell death (17, 30). Therefore, based on the substitution mutations A74D and A75P in the dimerization domain of TRF1 that decrease homodimerization, as assessed by a decrease in telomeric DNA binding in vitro and in vivo (10), hTRF2 was further mutated by introduction of the corresponding substitution mutations V52D and N53P. These additional mutations should reduce the dominant-negative activity resulting from the mutation in the myb-like domain. The compound mutant protein, called hTRF2DPV, was fused to the N terminus of the YFP, and the resultant chimera was transiently expressed in human LM217 cells. We found that the described mutations abolished telomeric localization of hTRF2, as evident from the diffuse nuclear staining of hTRF2DPV-YFP compared to the punctate localization of wild-type hTRF2-YFP (Fig. 5A). Although this effect was less pronounced when hTRF2DPV was fused to hTERT (see below and data not shown), it is clear that there is a telomere-binding defect inflicted upon hTRF2 when the myb-like domain is mutated.

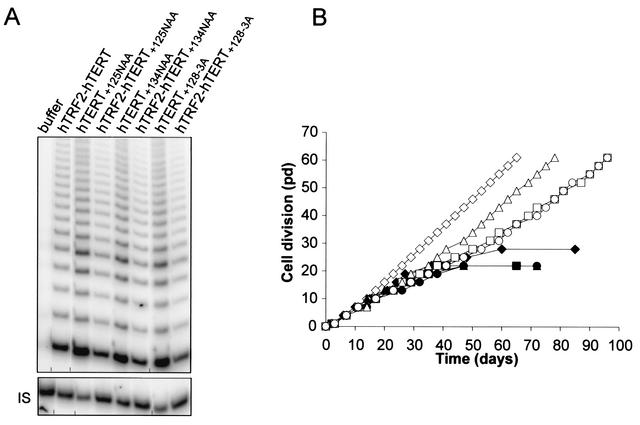

FIG. 5.

DNA binding activity of hTRF2 is required to rescue the in vivo function of an hTERT DAT mutant. (A) Telomeric localization of hTRF2 is lost upon mutation of the DNA binding and dimerization domains. An example of an LM217 cell(s) transiently expressing hTRF2DPV-YFP or hTRF2-YFP is shown as a differential-interference contrast image (right) to visualize the cells and as a fluorescent image (left) to visualize the YFP-tagged protein. (B) Stable expression of hTRF2DPV-hTERT in HA5 cells. Lysates isolated from HA5 cells expressing the described constructs were immunoblotted with an anti-flag (α-flag) antibody to detect ectopic hTERT. Actin served as a loading control. (C) Fusion of hTRF2DPV to hTERT does not affect telomerase activity. Extracts isolated from HA5 cells stably expressing the described proteins were assayed for in vitro telomerase activity. The internal standard (IS) served as a positive control for PCR amplification. (D) hTRF2DPV-hTERT+128 cannot immortalize human cells. The life spans of HA5 cell lines expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128 (•), hTRF2DPV-hTERT+128 (○), hTRF2-hTERT (▪), hTRF2DPV-hTERT (□), or an empty vector (▴) are plotted against time.

The hTRF2DPV protein was next fused to the wild-type or the +128 DAT mutated version of hTERT and stably expressed in HA5 cells (Fig. 5B). Since the fusion of hTRF2DPV to either protein had no affect on telomerase activity (Fig. 5C), we addressed whether the mutated hTRF2 molecule could rescue DAT function. We found that cells expressing the hTRF2DPV-hTERT fusion protein proliferated beyond crisis, although their growth rate was lower than that of cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT (Fig. 5D), possibly because the hTRF2DPV molecule still has residual dominant-negative activity. This fusion protein also did not elongate telomeres like hTRF2-hTERT, arguing that the hTRF2DPV-hTERT protein is indeed crippled in its ability to bind telomeric DNA in vivo (not shown). Importantly, we found that cells expressing hTRF2DPV fused to the DAT mutant hTERT+128 entered crisis at the same time as vector control cells (Fig. 5D). Thus, a loss of DNA binding activity in hTRF2 abolished the ability of this protein, when fused to hTERT+128, to rescue the loss of DAT function in vivo.

Restoration of in vivo function of hTERT+128 requires direct fusion to hTRF2.

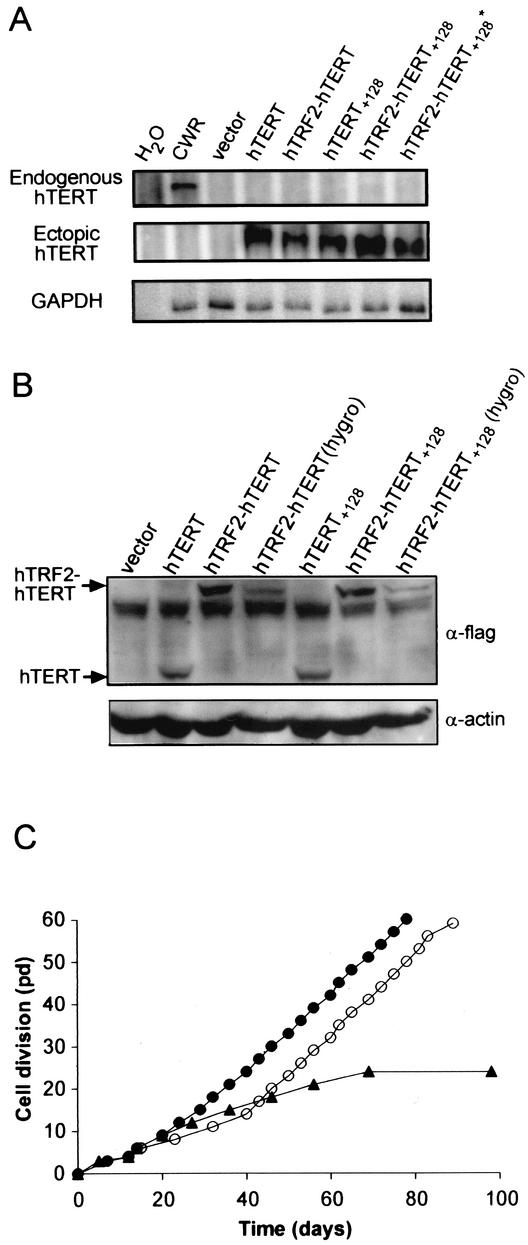

hTERT+128-expressing cells rarely proliferated beyond crisis (observed only once in eight independently generated cell lines), while rescue of the in vivo function of hTERT+128 by fusion to hTRF2 was highly reproducible, as identical results were obtained with six independently created HA5 cell lines expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128 (not shown). Although highly unlikely, the rescue of cellular immortalization of hTRF2-hTERT+128 in each of these cases could be attributed to spontaneous reactivation of the endogenous hTERT gene. To rule out this remote possibility, we RT-PCR amplified RNA isolated from these cells with primers specific for endogenous and, as a control, ectopic hTERT transcripts. As expected, ectopic hTERT was detected in HA5 cells expressing either wild-type or mutant versions of hTERT and absent in vector control cells. Endogenous hTERT was not detected in these cells, even at late postcrisis passage, despite the fact that this transcript was readily detectable in a telomerase-positive control cell line (Fig. 6A). Thus, the immortal life span of the HA5 cells could be ascribed specifically to the ectopic expression of the hTRF2-hTERT+128 transgene.

FIG. 6.

Fusion with hTRF2 underlies the rescue of DAT mutants of hTERT. (A) Endogenous hTERT expression is absent in HA5 cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128. Total RNAs isolated from early (pd 1) infected HA5 cells and in some cases late-passage (pd 44 [asterisk]) HA5 cells expressing hTRF2-hTERT+128 were RT-PCR amplified with primers specific for ectopic or endogenous hTERT or, as a control, GAPDH mRNA content. Telomerase-positive CWR22-RV1 cells served as a positive control, whereas vector-infected HA5 cells or water alone served as a negative control for endogenous hTERT expression. (B) Equivalent expression of hTERT+128 and hTRF2-hTERT+128. Lysates isolated from HA5 cells expressing the described constructs were immunoblotted with an anti-flag (α-flag) antibody to detect ectopic hTERT or hTRF2-hTERT protein. Hygro indicates cells infected with pBabehygro constructs, which express proteins at lower levels. Actin served as a loading control. (C) Reduced expression of hTRF2-hTERT+128 still immortalizes HA5 cells. The life spans of HA5 cell lines infected with the low-expression pBabehygro vectors encoding hTRF2-hTERT (•), hTRF2-hTERT+128 (○), or vector alone (▴) are plotted against time.

We note that the expression of the fusion proteins was greater than that of the hTERT proteins (Fig. 2A), which could explain why the hTRF2-hTERT+128 protein was functional in vivo whereas the hTERT+128 protein was not. To rule out this possibility, we stably expressed hTRF2-hTERT+128 and hTRF2-hTERT in HA5 cells using a different construct (pBabehygro) which, by immunoblot analysis, expressed the fusion proteins at levels equivalent to or less than those of HA5 cells previously shown to express hTERT or hTERT+128 (Fig. 2A and 6B). We found that cells expressing low levels of hTRF2-hTERT+128 proliferated beyond vector control cells (Fig. 6C). In fact, expressing hTRF2 fused to the other three DAT mutants (hTERT+128-3A, hTERT+125NAA, or hTERT+134NAA) using the same pBabehygro vector also promoted the proliferation of HA5 cells beyond crisis (not shown). These data support the conclusion that it is the targeting of DAT mutants to telomeres that underlies the rescue of these mutants.

Expression of the related telomere binding protein hTRF1 lacking its DNA binding domain causes telomere length to increase in telomerase-positive cells (29), possibly by destabilizing the telomere structure and allowing telomerase more access to telomeres. A similar alteration to hTRF2 greatly disturbs telomere stability (30). Thus, rather than rescuing the hTERT+128 mutation by targeting the protein to telomeres, the fusion of hTERT to hTRF2 could subtly alter hTRF2 function, increasing the access of the hTERT+128 protein to telomeres. To test if the rescue of hTERT+128 is a cis effect of the fusion with hTRF2 or a trans effect caused by the alteration of hTRF2 function, we assayed whether the simultaneous expression of hTERT+128 with either hTRF2 or hTRF2 fused at its C terminus to the irrelevant protein (YFP) to mimic the fusion of hTERT could restore telomerase function in vivo.

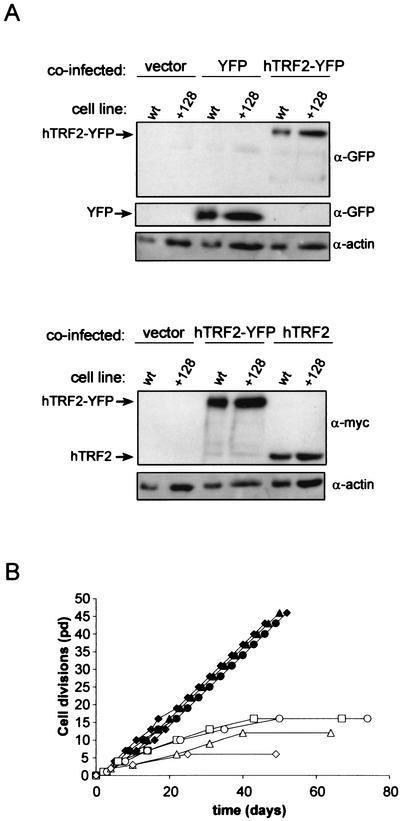

HA5 cells stably expressing hTERT+128 were infected with retrovirus encoding hTRF2, hTRF2-YFP, or, as negative controls, no transgene or YFP. To ensure that these constructs did not negatively affect cell growth, the retroviruses were also introduced into HA5 cells stably expressing wild-type hTERT. hTRF2, YFP, and hTRF2-YFP were confirmed by immunoblot analysis to be expressed (Fig. 7A). The ∼90-kDa band corresponding to hTRF2-YFP was also detected by an anti-YFP antibody, indicating that the entire fusion protein was produced (Fig. 7A). We find that HA5 cells expressing wild-type hTERT in combination with hTRF2 or hTRF2-YFP were, as expected, capable of immortalizing just as well as the same cells infected with a control empty vector or one encoding YFP (Fig. 7B). We also found that the simultaneous expression of either hTRF2 or hTRF2-YFP with hTERT+128 did not allow the growth of HA5 cells beyond that of vector or YFP control cells (Fig. 7B). As neither of these versions of hTRF2 immortalized hTERT+128-expressing cells, we conclude that the rescue of hTERT+128 by fusion with hTRF2 is a cis effect, through the targeting of hTERT to telomeres.

FIG. 7.

In vivo activity of hTERT+128 is restored only when directly fused to hTRF2. (A) Expression of YFP, hTRF2, or hTRF2-YFP in either hTERT- (wt) or hTERT+128 (+128)-infected HA5 cells. Lysates isolated from HA5 cells expressing the described constructs were immunoblotted with anti-GFP (α-GFP) or anti-myc antibodies to detect ectopic hTRF2. Actin served as a loading control. (B) Ectopic expression of hTRF2 does not immortalize HA5 cells expressing hTERT+128. The life spans of HA5 cells coexpressing hTERT and vector (▪), YFP (▴), hTRF2 (•), or hTRF2-YFP (⧫) or those coexpressing hTERT+128 and vector (□), YFP (▵), hTRF2 (○), or hTRF2-YFP (◊) are plotted against time.

Conclusions.

We previously identified a novel region within hTERT called the DAT domain that is essential for telomere elongation and cellular immortalization but not for telomerase catalytic activity (1). Since mutations in this domain do not disrupt the normal nuclear localization of hTERT (1), we hypothesized that the DAT domain might mediate interactions with telomeres. To test this hypothesis, we targeted hTERT bearing mutations in the DAT domain to telomeres by fusing the mutated proteins to the telomere binding protein hTRF2. We demonstrated that this fusion relocalized hTERT protein to telomeres, since the fusion protein colocalized with a telomere binding protein, the fusion with wild-type hTERT greatly increased telomere length, and this effect was not observed when the telomere binding activity of hTRF2 was lost. Here, we show that targeting the DAT mutant of hTERT to telomeres rescued the DAT mutation, arresting telomere shortening and immortalizing human cells. Interestingly, mutations in the N terminus of this domain were not rescued in this fashion (not shown), suggesting that other functions in addition to telomere targeting may reside in this region of the protein.

Since the rescue of the DAT mutation occurred only when the mutated hTERT protein was fused directly to an hTRF2 protein having a functional DNA binding domain but not when hTRF2 was coexpressed with hTERT+128, we argue that mutations in the DAT domain disrupt the proper interaction between telomerase and telomeres. Tethering hTERT+128 to telomeres by fusion to hTRF2 allows this biochemically active mutant to elongate telomeres due to its close proximity to its substrate. Because hTRF2 and hTERT did not interact in vitro (not shown), the fusion likely mimics a telomerase recruitment process that may not directly involve hTRF2. Formally, it remains possible that DAT-mutated hTERT proteins still reside on telomeres, although not detected by immunofluorescence, and are translocated by the fusion with hTRF2 from a proximal region of the telomere to a region closer to the end. However, more consistent with the distribution of hTERT throughout the nucleus is a model whereby hTRF2 actually relocalizes hTERT from the nucleoplasm and nuclear structures to telomeres.

We speculate that the telomere localization of telomerase by the DAT domain could be a key step in the regulation of enzyme activity in vivo, and possibly even telomere length. In support of this model, despite equal levels of catalytic activity in cells expressing wild-type hTERT alone and fused with hTRF2, a dramatic elongation of telomeres is observed only in cells carrying hTRF2-hTERT, which is targeted more efficiently to telomeres. Given that the sequence of the DAT domain may be weakly conserved in lower eukaryotes (33) and that a single mutation in the yeast catalytic subunit in a position similar to that of the DAT domain of hTERT renders the yeast protein catalytically active but unable to elongate telomeres (11), we suggest that the recruitment of telomerase to telomeres by the DAT domain may be an evolutionarily conserved function of TERT. Lastly, inhibiting the catalytic subunit of telomerase, and hence telomere elongation, by the expression of dominant-negative hTERT greatly impedes, if it does not abolish, tumor cell growth (13, 15). Thus, targeting the DAT domain to prevent telomerase binding to telomeres may hold promise as a complementary means to inhibit telomerase activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Counter laboratory for advice, Danny Lew for critical review of the manuscript, and Corinne Linardic and Diane Downie for technical assistance. C.M.C. is especially grateful to Silvia Bacchetti for review of the manuscript and her continued support, guidance, and insight.

This work was supported by NIH grant CA82481. B.N.A. is supported by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Pre-Doctoral Fellowship. C.M.C. is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armbruster, B. N., S. S. Banik, C. Guo, A. C. Smith, and C. M. Counter. 2001. N-terminal domains of the human telomerase catalytic subunit required for enzyme activity in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7775-7786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann, P., and T. R. Cech. 2001. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science 292:1171-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn, E. H. 2001. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106:661-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broccoli, D., A. Smogorzewska, L. Chong, and T. de Lange. 1997. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat. Genet. 17:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong, L., B. van Steensel, D. Broccoli, H. Erdjument-Bromage, J. Hanish, P. Tempst, and T. de Lange. 1995. A human telomeric protein. Science 270:1663-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Counter, C. M., W. C. Hahn, W. Wei, S. D. Caddle, R. L. Beijersbergen, P. M. Lansdorp, J. M. Sedivy, and R. A. Weinberg. 1998. Dissociation among in vitro telomerase activity, telomere maintenance, and cellular immortalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14723-14728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etheridge, K. T., S. S. Banik, B. N. Armbruster, Y. Zhu, R. M. Terns, M. P. Terns, and C. M. Counter. 2002. The nucleolar localization domain of the catalytic subunit of human telomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 277:24764-24770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans, S. K., and V. Lundblad. 1999. Est1 and Cdc13 as comediators of telomerase access. Science 286:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, S. K., and V. Lundblad. 2000. Positive and negative regulation of telomerase access to the telomere. J. Cell Sci. 113:3357-3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairall, L., L. Chapman, H. Moss, T. de Lange, and D. Rhodes. 2001. Structure of the TRFH dimerization domain of the human telomeric proteins TRF1 and TRF2. Mol. Cell 8:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman, K. L., and T. R. Cech. 1999. Essential functions of amino-terminal domains in the yeast telomerase catalytic subunit revealed by selection for viable mutants. Genes Dev. 13:2863-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith, J. D., L. Comeau, S. Rosenfield, R. M. Stansel, A. Bianchi, H. Moss, and T. de Lange. 1999. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell 97:503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, C., D. Geverd, R. Liao, N. Hamad, C. M. Counter, and D. T. Price. 2001. Inhibition of telomerase is related to the lifespan and tumorigenicity of human prostate cancer cells. J. Urol. 166:694-698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn, W. C., C. M. Counter, A. S. Lundberg, R. L. Beijersbergen, M. W. Brooks, and R. A. Weinberg. 1999. Creation of human tumour cells with defined genetic elements. Nature 400:464-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hahn, W. C., S. A. Stewart, M. W. Brooks, S. G. York, E. Eaton, A. Kurachi, R. L. Beijersbergen, J. H. Knoll, M. Meyerson, and R. A. Weinberg. 1999. Inhibition of telomerase limits the growth of human cancer cells. Nat. Med. 5:1164-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt, S. E., W. E. Wright, and J. W. Shay. 1996. Regulation of telomerase activity in immortal cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2932-2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlseder, J., D. Broccoli, Y. Dai, S. Hardy, and T. de Lange. 1999. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science 283:1321-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, N. W., and F. Wu. 1997. Advances in quantification and characterization of telomerase activity by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP). Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2595-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lendvay, T. S., D. K. Morris, J. Sah, B. Balasubramanian, and V. Lundblad. 1996. Senescence mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with a defect in telomere replication identify three additional EST genes. Genetics 144:1399-1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lingner, J., T. R. Cech, T. R. Hughes, and V. Lundblad. 1997. Three Ever Shorter Telomere (EST) genes are dispensable for in vitro yeast telomerase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11190-11195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundblad, V., and J. W. Szostak. 1989. A mutant with a defect in telomere elongation leads to senescence in yeast. Cell 57:633-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murnane, J. P., L. Sabatier, B. A. Marder, and W. F. Morgan. 1994. Telomere dynamics in an immortal human cell line. EMBO J. 13:4953-4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura, T. M., and T. R. Cech. 1998. Reversing time: origin of telomerase. Cell 92:587-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouellette, M. M., D. L. Aisner, I. Savre-Train, W. E. Wright, and J. W. Shay. 1999. Telomerase activity does not always imply telomere maintenance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 254:795-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sedivy, J. M. 1998. Can ends justify the means? Telomeres and the mechanisms of replicative senescence and immortalization in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9078-9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seimiya, H., H. Sawada, Y. Muramatsu, M. Shimizu, K. Ohko, K. Yamane, and T. Tsuruo. 2000. Involvement of 14-3-3 proteins in nuclear localization of telomerase. EMBO J. 19:2652-2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shay, J. W., and S. Bacchetti. 1997. A survey of telomerase activity in human cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 33:787-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart, N., and S. Bacchetti. 1991. Expression of SV40 large T antigen, but not small t antigen, is required for the induction of chromosomal aberrations in transformed human cells. Virology 180:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Steensel, B., and T. de Lange. 1997. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature 385:740-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Steensel, B., A. Smogorzewska, and T. de Lange. 1998. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell 92:401-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinrich, S. L., R. Pruzan, L. Ma, M. Ouellette, V. M. Tesmer, S. E. Holt, A. G. Bodnar, S. Lichtsteiner, N. W. Kim, J. B. Trager, R. D. Taylor, R. Carlos, W. H. Andrews, W. E. Wright, J. W. Shay, C. B. Harley, and G. B. Morin. 1997. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat. Genet. 17:498-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright, W. E., V. M. Tesmer, M. L. Liao, and J. W. Shay. 1999. Normal human telomeres are not late replicating. Exp. Cell Res. 251:492-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia, J., Y. Peng, I. S. Mian, and N. F. Lue. 2000. Identification of functionally important domains in the N-terminal region of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5196-5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu, J., H. Wang, J. M. Bishop, and E. H. Blackburn. 1999. Telomerase extends the lifespan of virus-transformed human cells without net telomere lengthening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:3723-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]