Abstract

Clinical applications of magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) for the study of brain and prostate cancer have expanded significantly over the past 10 years. Proton MRSI studies of the brain and prostate have demonstrated the feasibility of noninvasively assessing human cancers based on metabolite levels before and after therapy in a clinically reasonable amount of time. MRSI provides a unique biochemical “window” to study cellular metabolism noninvasively. MRSI studies have demonstrated dramatic spectral differences between normal brain tissue (low choline and high N-acetyl aspartate, NAA) and prostate (low choline and high citrate) compared to brain (low NAA, high choline) and prostate (low citrate, high choline) tumors. The presence of edema and necrosis in both the prostate and brain was reflected by a reduction of the intensity of all resonances due to reduced cell density. MRSI was able to discriminate necrosis (absence of all metabolites, except lipids and lactate) from viable normal tissue and cancer following therapy. The results of current MRSI studies also provide evidence that the magnitude of metabolic changes in regions of cancer before therapy as well as the magnitude and time course of metabolic changes after therapy can improve our understanding of cancer aggressiveness and mechanisms of therapeutic response. Clinically, combined MRI/MRSI has already demonstrated the potential for improved diagnosis, staging and treatment planning of brain and prostate cancer. Additionally, studies are under way to determine the accuracy of anatomic and metabolic parameters in providing an objective quantitative basis for assessing disease progression and response to therapy.

Keywords: magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI), prostate and brain cancer, metabolism, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), morphology

Introduction

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) expands the diagnostic assessment of brain and prostate tumors by adding metabolic data to the morphologic information provided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Conventional MR imaging relies on abnormal signal intensities in T2-weighted or contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images to define the presence and extent of cancer. These morphologic assessments are not specific for cancer and may both under- and overestimate the spatial extent of active tumor. Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) is able to detect changes in cellular metabolites and has improved the discrimination of cancer from surrounding healthy tissue and necrosis.

The complexity of the anatomy of the brain and prostate, and the heterogeneity and multifocal nature of brain and prostate tumors place stringent requirements on the temporal and spatial resolution of the MRS data acquired. Although initial studies of the human brain and prostate used phosphorus (31P) MRS, its relatively poor sensitivity limited its utility because only coarse spectral and spatial resolution (>8 cm3) was attainable in a clinically reasonable amount of time [1–19]. The higher sensitivity of water and lipid suppressed proton (1H) MRS has allowed the acquisition of spectra from sufficiently small volumes (≈0.2–2 cm3) in an amount of time (≈15 minutes) that makes it clinically useful.

The acquisition of single voxel 1H MRS spectra from the brain and prostate and their analysis are commercially available, FDA approved, and are being clinically reimbursed in many institutions [20–26]. Although these techniques do provide important data, they are limited to studying clearly defined homogeneous lesions or diseases that affect all regions uniformly. Clearly the acquisition of data from a single region of interest is unable to provide information on the spatial extent and heterogeneity of cancer and relies on conventional MRI to provide information about the location of the cancer.

Over the past 15 years, there has been considerable progress in combining MRS techniques with methods for spatial localization such as slice selection and phase encoding [12,27–39]. Such multivoxel MR spectroscopic imaging techniques are referred to as MRSI or chemical shift imaging (CSI) and can provide arrays of contiguous spectra from regions of cancer and surrounding tissues. Early MRSI studies of human brain tumors have typically used phase-encoding in 2 dimensions across selected regions [24,34,40–42]. In more recent studies, the ability to obtain the three dimensional distribution of metabolites has been demonstrated to be critical for the accurate assessment of brain and prostate tumors.

There have also been considerable recent improvements in MRSI data acquisition and analysis techniques [43]. These improvements have had an impact on both the spatial resolution and the time required to acquire MRSI data, and have allowed the addition of MRSI to clinical MRI exams. Because MRI and MRS can be acquired within the same clinical exam, increasing numbers of combined MRI/MRS examinations have been performed on patients with brain or prostate tumors. In the following discussion, we review the state of the art in MRSI techniques and the current clinical role of combined MRI/MRSI. We begin with a discussion of the MRSI data acquisition, processing and display techniques. In the following two sections on proton MRSI of brain and prostate tumors we discuss: the metabolic information that can be acquired using MRSI, how metabolic information compliments the anatomic information provided by MRI and other functional information provided by positron emission tomography (PET) and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI, the clinical utility of combined MRI/MRSI in the diagnosis, staging, treatment planning, and follow-up of patients with brain and prostate cancer. The sections are written such that those not interested in the technical aspects of MRSI data acquisition can go directly to the sections on MRSI of brain and prostate tumors.

Proton MRSI Acquisition Techniques in the Brain and Prostate

Water-suppressed 1H spectroscopy techniques are now available for obtaining spectra from selected regions within the brain and prostate and can be combined with additional localization to produce either a single spectrum from a region of interest (single-voxel MRS) or a multidimensional array of spectra from the region of interest (multivoxel MRS or spectroscopic imaging) [12,23,27,28,44–48]. Several technical hurdles must be overcome to detect the resonances of biologically relevant compounds. These include accurate localization to often small regions of interest, detection of the relatively small metabolite signals in the presence of the an approximately 1000-fold higher 110 M H20 resonance and the ability to avoid spectral contamination from surrounding lipids.

Spectral Localization

The most commonly used sequences for 1H MRS provide localization to a single voxel by selective 90°-90°-90° (STimulated Echo Acquisition Mode (STEAM) [44]) or 90°-180°-180° excitation (Point REsolved Spatial Selection (PRESS) [46]). The STEAM technique can be used with shorter echo times but has an disadvantage in signal to noise and is more sensitive to diffusion loss of signal when compared to PRESS [45]. Although studies have shown that short echo time STEAM can provide an increased number of spectral resonances [34], the peaks most often used for tissue discrimination in brain and prostate cancer can be easily observed using the more sensitive longer echo time PRESS technique. The use of longer echo-delays also has improved water and lipid suppression in brain and prostate spectra and simplified the spectral analysis that was optimized to quantitate changes in choline, creatine, citrate and N-acetyl aspartate (NAA). With improved gradient technology, echo times of the PRESS sequence can be reduced to that of STEAM, and future studies will exploit the increased chemical information that can be obtained at shorter echo times.

Single-voxel MR studies are limited in the information they can provide and often suffer from improper or imprecise localization because their location is determined from MR images that often cannot differentiate between tissue types. For heterogeneous lesions the exact choice of voxel size and position has a critical impact on the spectra. It is often very difficult to attain perfect placement of the localized volume without spectral contamination from adjacent tissues, even when the region of interest is the same size or even slightly larger than the selected voxel size. Another major limitation for single-voxel studies is the inability to assess the spatial distribution of observed metabolic changes that would provide valuable information for studies of response to therapy and degree of local control. To overcome the limitations of single-voxel techniques, recent studies have added phase-encoding techniques [12,28] to obtain localized spectra from arrays of multiple contiguous voxels. PRESS or STEAM localization is used to select a region of usually 50 cm3 or larger and phase encoding in 1, 2, or 3 spatial dimensions is applied to yield arrays of spectral voxels. In addition to providing spectra throughout the volume of interest, 3D MRSI has the advantage that the experimental conditions only stipulate the size of individual voxels. The spatial position of the spectra can be selected retrospectively through “voxel-shifting”, using the appropriate mathematical weighting of the raw data based on the translation property of the Fourier transform [49,50]. Besides removing the guess work on the location of abnormal metabolite levels, this feature allows retrospective alignment of the spectra to regions of suspicious morphology within a study, and with data from other exams and locations from other imaging techniques.

Improved Localization

A recent technical enhancement for 1H MRS has been the substitution of optimally shaped rf pulses that provide improved excitation profiles compared to more conventional sinc pulses. For low tip angles reasonably good slice profiles can be obtained, but for 90° and especially 180° excitations, optimized pulses are essential for good slice profiles [51]. Due to the imperfect profiles of the PRESS spin echo pulses, even those generated by the Shinnar-Le Roux algorithm, significant contamination from lipids outside the PRESS selected region can still occur. This problem is compounded in MRSI studies because the lipid contamination can be spread throughout the data due to the point spread function of the MRSI sampling [39,52–55]. To solve this problem, several groups have employed outer volume saturation (OVS) sequences to better conform the PRESS selected volume to the volume of interest. Initial out-of-volume saturation schemes employed either 4-msec sinc-gauss pulses [39] or 1-msec small flip-angle sinc-pulses [52–55]. However, the spatial selectivity of these pulses was not optimum with transition bands of up to 1 cm. Due to the low spatial selectivity and nonrectangular suppression profiles of these pulses, residual unsuppressed water and lipid signals at the bands' edges often gave rise to incomplete suppression of the large lipid signal. More recently, spatial suppression pulses with very high selectivity and excitation bandwidths have been developed by Le Roux et al. [56]. These pulses have been added to PRESS/MRSI studies of brain and prostate tumors and have allowed coverage of the entire brain and prostate without contamination from surrounding lipids [57,58]. Additionally, the problems of both chemical shift misregistration and nonideal excitation profile of the PRESS selected volume have been addressed by overprescribing the PRESS volume and applying the very selective suppression (VSS) pulses to better define the sides of the box [59]. The ability to conform the PRESS selected region to arbitrary polygons (instead of simple cuboids) virtually eliminates spectral contamination from lipids outside the region of interest.

Water and Lipid Suppression

Techniques for water suppression have usually involved frequency selective saturation pulses and required that the region of interest was well shimmed (CHESS) [60]. Lipid suppression has been achieved by the selective excitation of a region inside the skull or prostate or by a combination of frequency and/or spatially selective pulses and inversion recovery (STIR) [61]. These approaches required optimization for each individual study, and even after optimization, often demonstrated inadequate water and lipid suppression resulting in baseline artifacts and difficulty in quantifying metabolites [47,48,57,62]. Like volume selection, water and lipid suppression has also been enhanced by use of shaped pulses designed using the Shinnar-Le Roux algorithm [51]. One recent example of this is the use of band selective inversion with gradient dephasing (BASING) for water and lipid suppression [47]. BASING, which consists of a frequency selective RF inversion pulse surrounded by spoiler gradient pulses of opposite signs, was used to dephase water or water and lipid and minimally impact metabolite resonances. The incorporation of two BASING pulses in a PRESS/CSI sequence has allowed for improved spectroscopic coverage of the prostate, with robust water and lipid suppression [47,57]. Alternatively, by replacing both 180° pulses in the PRESS sequence with phase compensating spectral/spatial pulses designed using the Shinnar-Le Roux algorithm, robust water and lipid suppression was achieved with the added advantage of reducing the chemical shift misregistration of the PRESS volume [48,57].

Improved Spatial Coverage

Due to its relatively small size, spatial coverage of the entire prostate can be achieved using PRESS/CSI in a clinically reasonable amount of time. However, coverage of the entire brain for the study of multifocal or metastatic cancer is currently limited by the techniques available for suppressing fat and the time required to encode the spatial dependence of the data. In some of the initial work in this area, Spielman et al. [63] used spatially and frequency selective pulses to excite slices inside the brain and then applied 2D phase encoding to acquire multislice 1H-MRSI data. The spectra obtained in this manner were from 1.5-cm-thick slices and with an in-plane resolution of 7 mm. Typical acquisition times were of the order of 30 minutes. Duyn et al. [32] took a slightly different approach to obtain data from the brain at a 2 cm3 spatial resolution. They first applied presaturation in multiple planes to eliminate fat signals and then performed 2D phase encoding with a conventional spin echo acquisition. In addition to making use of multislice techniques, they also acquired and analyzed multiple echo data [64] to reduce the time needed to cover the brain to around 9 minutes. However, the echo times required for these sequences were relatively long (270 msec or greater) and the spectral resolution was limited by the time available for data acquisition. More recently, techniques that employ oscillating gradients and echo planar spatial-spectral strategies have been used to obtain MRSI data in a time-efficient fashion [31,33].

Improved Spatial Resolution

For MRSI studies of cancer there are three great advantages to improving spatial resolution: 1) allowing the study of smaller tumors; 2) reducing the occurrence of mixed spectral pattern due to multiple tissue types in each voxel; 3) improving accuracy in measuring volumes of tissues with abnormal metabolite patterns. One of the major limitations of in vivo MR spectroscopy has been its low sensitivity and consequently its poor spatial resolution. Although MRS studies of the brain obtained with volume head coils have demonstrated great potential for discriminating regions of tumor, necrosis and neuronal tissue, voxel size is a limiting factor in determining the clinical utility of the technique. In analyzing the factors that limit sensitivity, we found that the greatest gain could be realized by improved MR coil design [65,66]. Typically, the volume head coil used for brain MRI is also used for 1H MRS. In this set up the spectral signal arises from 1 to 2 cm3 of tissue whereas the sample noise is acquired from the entire sensitive volume of the coil that includes the whole head, neck and sometimes shoulders as well. To improve the signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio of the spectral data, we have designed more sensitive detectors (surface and phased array coils) to improve sensitivity and to limit the detection of sample noise as much as possible [65,66]. This has allowed a fourfold increase in the spatial resolution of the spectra acquired. In studies of brain tumors at UCSF, PRESS selected volumes have been typically between 50 and 400 cm3 with phase encode matrices of 8x8x8 or 16x8x8, and nominal voxel sizes of 1 to 2 cm3 with head coils, whereas surface or phased array coil studies have had spectral resolutions between 0.2 to 4 cm3.

One drawback to the use of surface and phased array coils is that their inhomogeneous reception profiles can complicate data interpretation. To compensate for this effect, an analytical technique can be used to model and correct for the reception profile of each coil design, size and position [67]. In this method a theoretical reception profile is calculated on a computer workstation for each coil geometry. This coil map is then aligned to MR data using aqueous coil markers which appear in the MR images. Once the coil position and orientation are defined, the MR image data are divided by the aligned coil map. This method is extremely flexible and only requires a few minutes of processing time for each image set. It has also been shown to be highly accurate for both MRI and MRS data acquired from phantoms and humans on our 1.5 T MR instrument. For example, images acquired from a uniform phantom demonstrated a 20-fold decrease in image intensity before correction but only a 10% standard deviation after analysis [67].

Improved Chemical Specificity

The use of clinical MR systems with field strengths ≥3 T can both increase the spatial resolution of the data acquired and improve chemical shift dispersion thereby reducing the overlap of metabolites in the proton spectrum. Although changes in choline, creatine, NAA and citrate have already been clinically useful in the identification of brain and prostate cancer, we are only scratching the surface of chemical specificity possibly obtainable using in vivo MRS. As new metabolic markers for brain and prostate cancer are identified, clinical MR scanners with higher magnetic field strengths will be critical for resolving these new markers from surrounding signals. Just a decade ago, the concept of performing in vivo NMR studies at high magnetic field strengths was challenged by skeptics due to rf power deposition problems, increased magnetic field susceptibility effects and changes in metabolite relaxation times. More recently, experience with high-field human (e.g., 3–4 T) systems has shown that many of the technical problems expected at high field can be overcome [68–70].

3D 1H-MRSI Data Analysis and Display

The main issues for data analysis and display are the reliability of the methods used for quantification of spectral parameters, the design of displays which can conveniently represent the multidimensional character of the data, and the ability to relate the spectral signals to particular tissues or regions of morphology. Because of the number of spectra that must be analyzed, the use of automated procedures for estimating peak parameters is also necessary.

Data Analysis

For the spectroscopy data, the first processing steps are to construct arrays of spectra by applying time domain apodization and Fourier transformation to reconstruct the chemical shift and spatial dependence of the data. In quantitating spectral parameters it is necessary to correct for constant and spatially dependent frequency and phase shifts as well as variable baseline due to broad resonances or residual water. Frequency and phase corrections may be achieved using a water reference or by using the spectra themselves to estimate correction parameters. Baseline corrections and estimation of peak parameters are best achieved using prior knowledge of the approximate relative position of the major peaks in the spectrum. Peak areas may be estimated by integration between a range of different frequencies or by fitting baseline subtracted data as a sum of components with particular lineshapes [29,30,71–73]. Whichever fitting algorithm is used, the number of spectra involved make it critical that the procedure is fully automated, as well as robust to low signal to noise and missing peaks.

Although the relative intensities of different metabolite peaks should be comparable, absolute intensities may vary as a function of space due to the combined effects of the box selection and nonuniformity in reception profile of the rf coil. These effects must be taken into account in making direct comparisons between spectra from different spatial locations. The theoretical reception profile of the coil must be sampled in the same way as the MRI data. For PRESS-MRSI this requires a knowledge of both volume selection and phase encoding parameters. For voxels that lie at the edge of the box, the influence of chemical shift on the apparent location of the selected box is also relevant, depending on the procedures used for volume selection.

Data Display

The visual correlation and statistical analysis of the spectral and imaging data are extremely important for interpretation of the data. Several different approaches have been used to display the information from multidimensional localized spectra and to correlate spatial variations in metabolites with the anatomy [12,19,36,74–76]. These include superimposing a grid on the MR image and plotting the corresponding arrays of spectra, calculating images of the spatial distribution of metabolites and overlaying these images on the corresponding MR images. These formats provide an excellent summary of the spatial distribution of different metabolites enabling rapid identification of regions of suspected abnormal signal and facilitating correlation with the anatomy. Because the same gradients are used for imaging and spectroscopy acquisitions, the data sets are already in alignment and can be overlaid directly.

Proton MRSI of Brain Tumors

Conventional MRI has practical limitations for assessing the presence and extent of brain tumors. The basis for visualizing tumor presence by MRI is that most brain tumors demonstrate a compromised blood brain barrier and therefore enhance after injection of a contrast agent such as gadolinium:DTPA (see Gilles et al., this volume). The contrast-enhancing volume is normally considered to define the region of tumor and is the basis for planning localized therapy. In practice, the contrast-enhancing region is often not an accurate reflection of the true extent of active tumor. This is due both to the existence of tumor tissue that does not enhance and to the presence of contrast-enhancing necrosis. In a recent review of 100 patients with primary brain tumors who had both contrast-enhanced MRI and 3D MRSI performed, a significant number of patients (76%) demonstrated abnormal metabolism (from MRSI) outside of the contrast enhancing lesion [77]. Although the lesion on T2-weighted images are generally larger and may encompass the tumor, T2-weighted images also reflect nonspecific effects such as edema and inflammation. These factors produce uncertainty concerning the reliability of MRI techniques for defining the tumor and evaluating therapeutic success. Accurate assessment of the presence and extent of viable tumor requires additional methods based on some functional or metabolic aspect of the cancer. The studies described in the following sections demonstrate that 1H-MRSI can detect metabolic differences between cerebral neoplasms and adjacent brain tissues and between viable and necrotic tissue.

Proton Single-Voxel MRS of Brain Tumors

The majority of human proton MRS studies of cancer have been carried out in the brain because of the relative ease of adequate water suppression, lipid suppression, and favorable signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). These studies have demonstrated dramatic spectral differences between normal brain tissue and brain tumors. MR spectra from regions of tumor demonstrate reduced NAA signal intensities in brain tumors compared with normal brain spectra. The loss in NAA presumably reflects a reduction in neuronal cell density within the tumor mass because NAA has been shown by labeled antibody studies to be confined to neurons [78]. A higher than normal choline resonance is also typically observed in brain tumors, presumably due to altered membrane phospholipid metabolism, mobility, and composition. Choline is an important compound involved in membrane phospholipid metabolism and is elevated in regions of dense, proliferative cells such as neoplasms. Creatine, which is a metabolite in bioenergetic pathways, is typically reduced in brain tumors but can vary as is demonstrated in Figure 1. High lactate levels, indicating anaerobic metabolism, have been detected in some tumors or regions of tumors but are highly variable. Spectra from necrotic regions and cerebral cysts typically demonstrate none of the metabolite resonances found in normal brain or solid tumors with the possible exception of lactate.

Figure 1.

Selected axial and sagittal spectral arrays from a 3D MRSI study of a poorly enhancing glioblastoma multiforme before brachytherapy. Regions of elevated choline and reduced (or absent) NAA resonances corresponded spatially to the tumor mass. The three-dimensional MRSI acquisition provided a total of 140 spectra from voxels located within the mass and in neighboring brain tissue. (From Ref. [94]; with permission.)

A multisite, 15-institution trial of single-voxel MRS was recently conducted in 86 cases of patients with glial tumors [79]. This study demonstrated that glial tumors had significantly elevated intensities of choline signals, decreased intensities of creatine, and decreased intensities of NAA compared to normal brain. On average, choline signal intensities were highest in astrocytomas and anaplastic astrocytomas and creatine signal intensities were lowest in glioblastomas. However, this study found that these metabolic characteristics exhibited large variations within each subtype of glial tumors and the resulting overlap precluded diagnostic accuracy in the distinction of low- and high-grade tumors. Recently however, studies using sophisticated data analysis techniques have shown a higher degree of accuracy both for in vitro and for in vivo spectroscopy studies of tumor grading [80–82]. One study by Preul et al. demonstrated a significant improvement in accuracy using these techniques (99%) compared to the primary preoperative clinical diagnosis (77%) for 91 patients with brain tumor [81].

Accuracy of Single-Voxel MRS in the Diagnosis of Brain Tumors

Since 1995, MRI-guided single-voxel MRS examinations have been performed by Drs. Rand, Haughton, Prost and Mark at the Medical College of Wisconsin in patients with suspected brain neoplasms on MRI or CT [83,84]. The primary objective has been to discriminate neoplasms from non-neoplastic brain diseases that can mimic tumors such as subacute infarcts, abscesses, and tumefactive demyelinating disease in untreated patients, or posttreatment effects such as radiation necrosis in patients with cancer. A conventional single-voxel PRESS technique with CHESS water suppression at 0.5 T has consistently generated shimmed water linewidths of 2 to 3.5 Hz and diagnostic quality spectra from 1- to 3-cm3 voxels in 6 to 8 minutes [83]. Whenever possible, a solid, gadolinium-enhancing portion of a lesion was interrogated to avoid sampling nonspecific, necrotic tissue. Clinical MRS exams were interpreted by visual inspection analogous to the qualitative interpretation of EKG or EEG recordings.

An initial consecutive series of patients at Medical College of Wisconsin who received MRS and whose final diagnosis was established by histologic exam (50 lesions) or by serial MR studies and clinical follow-up (five lesions) yielded 42 neoplasms and 13 non-neoplasms [84]. With four blinded MRS readers, the average sensitivity and specificity for the presence or absence of neoplasia were 0.85 and 0.74, respectively [84]. The sensitivity and specificity with nonblinded readers, in which the MR spectra were interpreted with the benefit of the clinical history, laboratory results and MRI, increased to 0.95 and 1.00, respectively. A trend of reduced diagnostic accuracy in 15 treated lesions versus 40 untreated lesions did not reach statistical significance. In many of the false negative errors, a large mobile lipid resonance was evident, indicating cellular necrosis. Although nonblinded readers generated no false-positives, the blinded readers who saw only the MRS data falsely interpreted 8 non-neoplastic lesions as neoplastic. These eight lesions included an ischemic infarction, radiation necrosis following treatment of a metastasis, vasculitis with infarction, a treated cerebral arteriovenous malformation with cavitated necrosis and hemorrhage, gliosis in the left cerebral peduncle, craniopharyngioma, demyelinating disease, and cerebral infarction. A very extensive white blood cell infiltrate was noted in most false positives, which was hypothesized as a source of elevated choline. The results from this study indicate that neoplastic lesions can be distinguished from non-neoplastic brain lesions with a high degree of diagnostic accuracy.

These investigators also assessed the clinical impact of single-voxel MR spectroscopy [85]. In a retrospective study of 90 consecutive patients studied with MRS at the Medical College of Wisconsin, patients were classified into two groups according to the official MRS report: group I was positive for neoplasm whereas group II was negative for neoplasm. Group I cases that had treatment without biopsy (radiation and/or chemotherapy) following MRS and group II cases treated medically or expectantly were classified as cases in which MRS had a positive impact on patient management. Conversely, group I cases in which surgical biopsy following MRS demonstrated non-neoplastic processes and group II cases with subsequent histologic diagnoses of neoplasm were classified as cases in which MRS had a negative impact. Eight of 49 group I cases (16%) and 15 of 30 group II cases (50%) were classified as impacted positively by MRS. Three cases in the series (4%) were classified as impacted negatively by MRS.

In Vitro MR of Excised Brain Tumors

A recent study by Kinoshita et al. obtained freeze-extracts in the operating room from 20 astrocytic tumors (11 glioblastomas, 3 anaplastic astrocytomas, and 6 low-grade astrocytomas) and 4 normal brain tissues obtained from lobectomized brain without tumor invasion or edema [86]. A part of each frozen sample was also examined histologically. Although the spectra of the solutions extracted from these tissues differ from those obtained from intact tissue in vivo, the results support the hypothesis that 1H MR metabolite levels can be used to characterize gliomas and differentiate the cancerous tissue from normal brain or necrosis. NAA was clearly detected in normal tissues but its concentration was very low in gliomas. Choline resonances were detected for all tumors and found that the “concentrations of choline-containing compounds increased with the malignancy, but decreased with greater necrosis in glioblastomas.” The latter finding is presumably due to a lower cell density in the glioblastomas with greater necrosis. Their results also support the in vivo finding that creatine levels vary between individual tumors. They found that total creatine decreased according to malignancy and the extent of necrosis and “suggest that a decreased total creatine peak indicates reduced energy reservoirs caused by rapid growth and ischemic changes”.

Magic-angle spinning (MAS) 1H MRS has recently been shown to enhance spectral resolution in NMR examinations of intact biologic tissue ex vivo [87–89]. High-resolution magic angle spinning HR-MAS 1H MRS, is rapid and requires only small amounts (≤15 mg) of unprocessed samples. Unlike chemical extraction or other forms of tissue processing, this method analyzes tissue directly, thus minimizing artifacts. Furthermore, the same tissue that has been assayed by high-resolution NMR can undergo further histologic, biochemical and genetic analysis. It has recently been shown to be useful in assessing neuronal damage in the case of Pick disease, a human neurodegenerative disorder, and in characterizing brain tumor types and grades [87–89].

2D 1H-MRSI of Brain Tumors

MR spectroscopic imaging studies of human brain tumors have typically used phase encoding in one and two dimensions across the selected regions [24,34,40–42]. In acquisitions requiring approximately 30 minutes, spectra were obtained throughout the tumor (two dimensions) and from neighboring brain tissue as well at spatial resolutions ranging from 1 to 3 cm3 Metabolite images that showed regions of high choline, low creatine and absent NAA corresponded spatially to the tumor lesion. In one patient study, a PET scan was also obtained and a region of high lactate levels corresponded to a region of increased 18F deoxyglucose uptake [41]. Another more thorough study of 50 patients by Fulham et al. also correlated 1H-MRSI levels (1 cm3 spatial resolution) with FDG-PET studies [40] but found lactate presence not to be a reliable indicator of malignancy. Their results showed choline to be increased above normal levels in most solid tumors. However, the normalized choline level was not an accurate discriminator of tumor grade because necrotic high-grade lesions exhibited reduced choline. Their results also support the potential to separate chronic radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence on the basis of choline levels.

3D 1H-MRSI of Brain Tumors

Spectroscopic imaging in three dimensions requires more complicated acquisition and analysis techniques and is not currently available on commercial, clinical MRI scanners. Several research groups have developed the necessary acquisition and analysis techniques for 3D proton SI and have applied these techniques to study human brain tumors [37,43,77,90–94].

In over 1100 MRI/MRSI studies performed on patients with brain tumor at UCSF, we have found the ability to obtain the 3D distribution of the metabolites to be critical for an accurate assessment of metabolic status within the lesion and in adjacent tissues. Figure 1 contains MR images, and MRSI spectra from a patient with a glioblastoma multiforme. The MRSI data was acquired in 17 minutes as an 8x8x8 array with a voxel size of 1.0 cm3 (1.0x1.Ox 1.0 cm3) from a 140 cm3 PRESS-selected region. The spectra demonstrate regions of relatively high choline and low or undetectable NAA levels that were spatially coincident with tumor mass. Spectra from regions of brain tissue beyond the mass demonstrated normal NAA, choline and creatine levels and the absence of observable lactate levels.

Figure 2 contains a graph of metabolite levels from 24 1H-MRSI exams of patients with subsequent histologic diagnosis of viable primary brain tumors [37]. Although there were great variations in the metabolite ratios, all regions of confirmed cancer (N=24 patients) demonstrated significant choline levels and a choline/NAA ratio above 1.3. This value is greater than four standard deviations above the mean ratio for 100 spectra obtained from 18 volunteer datasets. Mean normal values were found to be 0.52±0.13. In the five cases of histologically confirmed necrosis, the spectra demonstrated no significant (SNR<2.0) levels of choline, creatine or NAA. Variable levels of lactate/Lipids were observed (which could contain contributions from subcutaneous lipid in some cases). The results of this study indicated that 1) brain tissue exhibited significant levels of creatine, choline and NAA; 2) regions of significant choline levels and absent (or low) NAA resonances corresponded to solid tumor; 3) necrosis was characterized by a lack of choline, creatine and NAA. We found no consistent correlation with lactate levels that were variably present in tumor spectra, even within the same tumor mass. Although a general trend of higher choline was observed in higher grade tumors, this was offset by the presence of increased micronecrosis (lower viable cell density) in the highest grade cancers. The highest choline/ (normal choline) ratios were observed in oligodendrogliomas that were grades II or III cancers with very high cell densities.

Figure 2.

This graph summarizes the MRSI results from histology-proven viable brain tumors. The results demonstrated abnormal MR spectra in all tumors. Choline/NAA ratios were significantly (p<0.001) elevated, with no overlap with the normal values. (From: Proton Chemical Shift Imaging of Cancer. In Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Body (3rd ed). CB Higggins, H Hricak, and A Helms (Eds). Lippincott-Raven Press, New York; with permission.)

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) can monitor the rate of glucose uptake throughout the body and has been used to detect the metabolic differences between brain tissue, tumors and radionecrosis. Brain tumors usually demonstrate increased glucose uptake compared to normal brain whereas necrotic tissue is hypometabolic. Additionally, Di Chiro [95] noted a relationship between the histologic grade of some tumors and their glucose metabolic rate as measured by the FDG uptake. High-resolution FDG-PET and 3D MRSI data were compared in a recent study of 38 patients with malignant brain tumors [77]. Images from the MR and PET exams were aligned using an automated registration technique [96]. The PET and MRS agreed in 16 of 38 cases (Figure 3). In 12 of 38 cases, the MRSI was more definitive than PET in identifying tumor. Figure 4 shows an example where the MRSI detected clearly elevated choline levels and reduced NAA but the non-enhancing lesion is close to the cortex and the PET is unable to demonstrate elevated FDG uptake. The results of this study provided evidence that the MRSI may be more sensitive than FDG-PET in some cases for identifying regions of recurrent tumor.

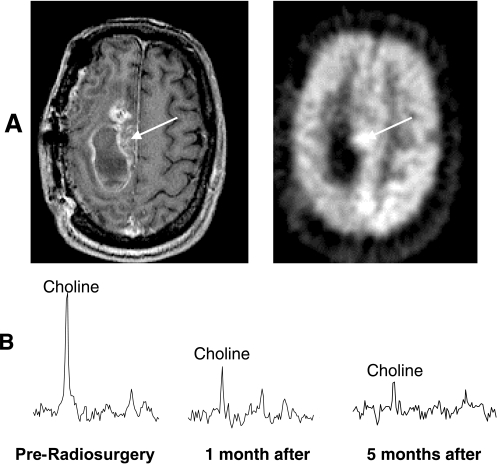

Figure 3.

MRI/MRSI and PET data from recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma before Gamma knife radiosurgery. The partially enhancing mass lesion seen on the post-gadolinium MR image (A, left) coincided spatially with the region of increased FDG uptake on the positron emission tomography image (A). The 1 cm3 spectral voxel centered on this lesion (B) demonstrated elevated choline and no NAA resonance. Following radiosurgery choline intensities in the spectra decreased significantly by 1 month and even further by 5 months. This example demonstrates the utility of MRSI for following radiosurgery treatment.

Figure 4.

MRI/MRSI and PET data of a recurrent patient with anaplastic astrocytoma. The MR images demonstrated a small region of enhancment (top left) and a larger region of high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (top middle). The PET scan demonstrated FDG uptake much lower than cortical gray matter (top right and was inconclusive for tumor). High-resolution 0.34 cm3 MRSI data were acquired using a figure-8 phased array coil placed at the top of the head. The choline resonance was highly elevated in the region of contrast enhancement but also extended posteriorly. Subsequent disease progression and surgical resection confirmed the presence of tumor. This study demonstrates the ability of high-resolution MRSI to not only detect viable cancer but also to assess the spatial extent of the non-enhancing regions of the tumor. (From Ref. [77]; with permission.)

With the development of improved MR hardware, it is now possible to measure parameters that reflect tissue vascularization by acquiring echo planar images during the first pass of a bolus of MR contrast agent. Changes in signal intensity of such dynamic data may be used to calculate an image of the regional cerebral blood volume (rCBV). In a comparative analysis of 19 examinations in which both MRSI and rCBV data were acquired from patients with gliomas, Henry et al. [77] found a correlation between rCBV and levels of choline in regions of abnormal metabolism. This was supported by quantitative analysis of corresponding regions of interest (R=0.96) and visual interpretation of images by two independent neuroradiologists. For regions believed to correspond to necrosis the mean normalized choline was 0.3 and mean rCBV was 0.4, whereas the values in putative tumor were 1.4 and 1.5 respectively. The differences between the two populations were statistically significant with a P value of less than .001. For circumstances where the rCBV was close to that of white matter, the MRSI data were more likely to provide definitive criteria for specifying tumor because of the complementary changes in choline and NAA which can be used to separate it from normal tissue.

Planning Focal Therapy

MR spectroscopic imaging has demonstrated the potential to assist in planning radiation and other focal therapy. In a recent study of 36 patients with recurrent gliomas, the spatial extent of the MRSI lesion before Gamma Knife radiosurgery was found to be predictive of clinical outcome [97]. Patients were categorized depending on whether their metabolic abnormality was within or extended beyond the region targeted for radiation treatment and their response assessed in terms of change in contrast-enhancing volume, time-to-further-treatment, and survival. The trends in the overall population were toward a more extensive increase in the percent contrast enhancing volume, a decreased time-to-further-treatment, and a reduced survival time for patients with more extensive initial metabolic abnormalities.

Statistical analysis of the subpopulation of patients with glioblastoma multiforme found a significant increase in relative contrast-enhancing volume (P<.01, Wilcoxon signed rank test), a decrease in time-to-further-treatment (P<.01, log rank test), and a reduction in survival time (P<.01, log rank test) for patients with regions containing tumor-suggestive spectra outside the Gamma Knife target in comparison with patients with spectral abnormalities restricted to the Gamma Knife target. The differences in survival were 10 versus 18 months respectively. Further studies would be needed to establish statistical significance for patients with lower grade lesions and to confirm the results in a larger population of patients. These findings suggest that clinical management and therapy selection for patients with brain tumors can be improved by the consideration of spectroscopic data.

Follow-up After Therapy

MR spectroscopic imaging has also demonstrated the potential to follow the effects of therapy [77,92,94]. Although limited in number, these studies have demonstrated a decrease in choline levels following successful therapy, i.e., a transformation from the tumor pattern of metabolite levels to that resembling necrosis. In cases of disease progression, an increase of voxels with abnormally high choline levels is expected. The correlation between MR parameters from serial examinations is based on volume MR image registration techniques [98] and permits an evaluation of both the morphologic and metabolic response to therapy. This type of analysis was the basis for evaluation of the prognostic significance of MRSI in studies of patients treated with Gamma Knife radiosurgery and allows the assessment of changes in metabolic profiles associated with many other types of therapy.

An example is provided by a recent study of 12 patients with glioblastoma multiforme, where serial MRI/MRSI was used to follow response to brachytherapy [77]. Individual proton spectra from the 3D arrays in these patients showed dramatic differences in spectral patterns in regions corresponding to brain tissue, radiation necrosis and recurrent or residual tumor. Figure 5 contains spectra obtained from a patient with glioblastoma multiforme before and after combined external beam radiation with a brachytherapy boost to the center of the mass. Spectra from the regions implanted with I-125 seeds demonstrated a dramatic reduction in choline levels within 10 weeks following therapy. Spectra from a region of tumor that received only external beam radiation showed a much slower reduction in choline levels. A region of brain tissue outside the tumor mass demonstrated no significant changes in metabolite levels.

Figure 5.

Sequential MR spectra from three spatial locations are shown following external beam radiation therapy with a brachytherapy boost. The spectra from a tumor volume that was within the implant target (top row) showed a dramatic decrease in choline by 10 weeks. Tumor spectra from a region outside of the implant target (middle row) showed a slower reduction in choline levels. Spectra from adjacent brain tissue (bottom row) showed no significant change during the 25-week study. (From Ref. [94]; with permission).

In 10 of the 12 cases, the metabolic information provided by MRSI demonstrated spectral differences between suspected residual/recurrent tumor and contrast enhancing radiation induced necrosis. In all 12 cases, there were abnormal spectral patterns consistent with solid tumor detected outside of regions of contrast enhancement. Changes in the aligned spectra included the significant reduction of choline levels after therapy indicating the transformation of tumor to necrotic tissue (5 of 12 cases). In 9 of 12 cases an increase in choline levels was observed in regions that previously appeared either normal or necrotic. This change correlated with clinical progression of the tumor in all nine cases. Several patients showed regional variations of response to brachytherapy as evaluated by MR spectroscopy. The observation of spectral patterns indicative of tumor in regions not enhancing on the MR images suggests that MR spectroscopy might also be valuable in defining the brachytherapy target volume. This study indicates that it is also possible to noninvasively monitor changes in proton MR spectra following focal therapy and that these data may add specificity to conventional MR imaging.

Proton MRSI of Prostate Tumors

The use of conventional MRI for the assessment of prostate cancer has been more controversial than for brain tumors. Its role has chiefly been the staging of disease (assessment of spread of cancer outside the prostate) rather than the detection and localization of cancer within the prostate [99–101]. The controversy has been due to the variable results reported for the diagnostic accuracy of MRI (54–90%) in the staging of prostate cancer [99,102–107]. Over the past several years more encouraging results have been obtained, with reported staging accuracies consistently between 75% and 90% [99,102,108–112]. The recent improvement in the performance of MRI is likely due to maturation of MRI technology, including improvements in MRI technique. Such improvements include; the use of combined endorectal/phased array coils for signal reception [99], analytical image correction for the endorectal/phased array coils [113], faster imaging sequences, a better understanding of morphologic criteria used to diagnose extraprostatic disease [111], and increased reader experience [111].

Prostate cancer is best identified by T2-weighted MRI as areas of reduced signal intensity in the normally high signal intensity peripheral zone. We have recently demonstrated that the use of T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) imaging and a pelvic phased-array incorporating an endorectal coil can markedly improve the evaluation of extracapsular extension (accuracy 81%; sensitivity for ECE 91%) and seminal vesicle invasion, thereby improving the staging of prostatic cancer [99].

The detection and assessment of intraglandular distribution of prostate cancer is becoming increasingly important, due to the emergence of disease-targeted therapy such as interstitial brachytherapy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, and cryosurgery. In addition, the location of tumor has recently been related to the risk of postprostatectomy tumor recurrence, with a higher risk when surgical margins are positive at the base than at the apex [114]. Studies evaluating clinical data, systematic biopsy, transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), and MRI have shown disappointing results for tumor localization within the prostate [115–118]. High-resolution endorectal MRI has demonstrated good sensitivity (79%) but low specificity (55%) in determining tumor location due to a large number of false positives [99,119]. This low specificity can be attributed to factors other than cancer (e.g., postbiopsy hemorrhage, and prostatitis) causing a decrease in signal intensity on T2-weighted images [118,120]. Additionally, after therapy the prostate is often significantly decreased in size and in most cases the distinction of normal prostatic zonal anatomy and pathology on T2-weighted images is lost [120–122]. Similar to the brain, an accurate assessment of the presence and extent of cancer requires additional methods based on some functional or metabolic aspect of the cancer.

Unlike the brain, conventional contrast-enhanced MRI has not provided any significant advantage in localizing prostate cancer within the prostate, or in assessing extraprostatic spread of cancer [123]. However, recent studies of the enhancement of prostate cancer during the first pass of contrast with fast dynamic imaging, has indicated that dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging may have a role in detecting and localizing cancer within the prostate [124–126]. Prostate cancer has been characterized by early and rapidly accelerating enhancement compared to surrounding tissues [125]. Pharmokinetic modeling demonstrated differences in the amplitude of the initial contrast upslope and contrast exchange rate between tumor and fibromuscular benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and for tumor and fibroglandular BPH, providing improved delineation of intraprostatic tumor extent compared with conventional MRI [126]. Additionally, poorly differentiated tumors showed the earliest and greatest rate of enhancement [125].

Preliminary studies using radiotracer 18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) have demonstrated that FDG-PET cannot reliably differentiate between primary prostate cancer and BPH, and that PET is not as sensitive as bone scintigraphy for the detection of osseous metastases [127–130]. However, FDG-PET may have a role in the detection of lymph node metastases in patients with prostate specific antigen relapse after primary local therapy [128,129,131]. Additionally, PET probes other than FDG have demonstrated greater success in detecting cancer within the prostate. A recent PET study using 11C choline has demonstrated that prostate cancer can be detected by increased uptake of choline into the cell to meet increased synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, an important cell membrane phospholipid that is elevated in prostate cancer [132]. Additionally, the radio-labeled polyamine (N-(3-[18F]fluoropropyl)putrescine) has also demonstrated potential for imaging prostate tumors due to its high uptake in prostate cancer [133].

Proton Single-Voxel MRS of Prostate Tumors

Ex vivo proton MRS studies of animal models, cell lines, and tissue extracts have all demonstrated low citrate and high choline levels in prostatic adenocarcinoma compared to normal prostatic peripheral zone tissue and BPH [26,134–139]. The recent development and use of endorectal surface coils has established the feasibility of obtaining both high resolution anatomic images [99,140–142] and localized proton (1H) magnetic resonance spectra from the in situ human prostate in a clinically reasonable amount of time [26,143–147]. Similar, to the ex vivo studies, in vivo single-voxel 1H MRS studies have also demonstrated a significant increase in prostate choline levels and a significant reduction in prostate citrate levels in regions of cancer (Figure 6). To date, changes in prostate lactate and lipid signals have not been monitored by in vivo MRS because this region of the spectrum needs to be suppressed due to the high probability of contamination from lipids surrounding the prostate. This is unfortunate because several studies have demonstrated the ability of the citrate to lactate ratio to discriminate prostate cancer from benign prostatic tissue and as an indicator of cancer aggressiveness [135,148,149]. Additionally, an early carbon-13 high-resolution NMR study [150], and a more recent proton HR MAS study [151] of surgical prostate cancer specimens have demonstrated elevated lipids in cancer relative to healthy prostatic tissue. Hopefully, future MRSI improvements will allow for the assessment of intraprostatic lactate and lipids.

Figure 6.

Fifty-eight-year-old man with pathologic stage pT3a prostate cancer, Gleason score 5. (A) Reception profile corrected FSE T2-weighted (TR5000/TE 102 msec) axial MR image through the midprostate obtained using an endorectal coil. A tumor focus (arrows) is seen as an area of decreased signal intensity in the peripheral zone of the right gland. (B) Histopathologic section (hematoxylin-eosin stain; magnification 100x) confirmed tumor in the peripheral zone of the right midgland (1) which abuts the inked prostatic margin (a) and is interspersed between normal prostatic glands (b). (C) 0.24 cm3 spectra obtained from area of imaging abnormality (1) in the right peripheral zone demonstrates elevated choline and reduced citrate, a pattern consistent with definite cancer. (D) MR spectra obtained from normal left peripheral zone (2) demonstrates a normal spectral pattern with citrate dominant and no abnormal elevation in choline. (From Ref. [191]; with permission.)

The decrease in citrate with prostate cancer is due both to changes in cellular function [152] and changes in the organization of the tissue that loses its characteristic ductal morphology [153,154]. Healthy prostatic epithelial cells possess the unique ability to synthesize and secrete large amounts of citrate into the prostatic fluids that are contained in the ducts that the epithelial cells line. In prostate cancer, malignant epithelial cells have demonstrated a diminished capacity for net citrate production and secretion [152]. A consequence of citrate production and secretion in normal and BPH prostatic tissues is an inefficient and low level of ATP production. Consequently, it is believed that the transformation of prostate epithelial cells from citrate secreting to citrate-oxidizing cells may be essential to the process of malignancy and metastasis [155]. Also, cancer causes a significant reduction in the volume of glandular ducts that normally contain high levels of citrate [153,154]. Accordingly, Costello et al. [152] and Cornel et al. [135] found a correlation between citrate levels in extracted prostate cancer specimens with the percentage of acinar structures seen histologically. Similarly, the amount of citrate in samples of BPH depend on the percentage of glandular versus stromal tissue present. Because an admixture of both stromal and glandular BPH exists in the central gland of patients with prostate cancer, the amount of citrate observed in BPH tissue has been very variable.

The mechanism for the elevation of the choline peak in prostate cancer is less understood. However, it appears that similar to other human cancers, the elevation of the choline peak is associated with changes in cell membrane synthesis and degradation that occur with the evolution of cancer [156–158]. Phosphatidylcholine is the most abundant phospholipid in biologic membranes and together with other phospholipids, such as phosphatidylethanolamine and neutral lipids, form the characteristic bilayer structure of cells and regulates membrane integrity and function [159,160]. Highresolution 31P and 1H NMR studies of surgical prostate cancer specimens have demonstrated that many of the compounds involved in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis and hydrolysis (choline, phosphocholine (PC), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), ethanolamine, phosphoethanolamine (PE), glycero-phosphoethanolamine GPE)) can be measured and are major contributors to the magnitude of the in vivo “choline” resonance [11,13,26,134,135,137,161]. There is evidence that changes in the levels of these phospholipid metabolites may correlate with cellular proliferation [162–165] and cellular differentiation [166–168]. Similar to the brain [86], changes in cell density may also need to be considered when explaining the elevated choline peak in prostate cancer.

3D 1H-MRSI of Prostate Cancer

The complexity of normal prostate zonal anatomy and the often small, infiltrative, and multifocal nature of prostate cancer requires the mapping of prostate metabolite levels at high resolution throughout the entire gland to be of clinical utility. This has been accomplished using a combination of PRESS volume selection with phase-encoding in two and three dimensions [36,169,170]. In over 2000 prostate MRI/MRSI studies performed at UCSF, the body coil has been used for excitation and the endorectal coil as part of a pelvic phased array was used for signal reception. PRESS selected volumes have been typically between 50 to 100 cm3 with phase encode matrices of 8x8x8 or 16x8x8, and a nominal voxel sizes 0.2 to 0.5 cm3 [36,169,171,172]. MRSI acquisition times for prostate studies are typically 17 minutes.

Similar to surface coil studies of the brain, the inhomogeneous reception profile of the endorectal and external (pelvic phased array) surface coils must be taken into account before interpreting the MR images. If uncorrected, MR images exhibit very high signal intensity close to the coil and lower signal intensity further into the prostate (Figure 7A). Even with continuous adjustments with image windowing and leveling, it is difficult to interpret uncorrected images. The problem with interpretation is further complicated if there is a slight misplacement (i.e., tilt of the coil relative to the prostate) of the endorectal coil. This problem has been addressed by analytically correcting the images for the reception profile of the endorectal coil, thereby eliminating near-coil high signal intensity artifacts [67,113]. This postprocessing correction has been found to be very robust and has resulted in a dramatic improvement in the ability to interpret endorectal coil images (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Comparison of axial endorectal coil/pelvic phased array FSE prostate images (A) beforeand (B) after performing an analytic correction for the reception profiles of the endorectal and pelvic phased array coils. In the corrected image, the high signal intensity close to the endorectal coil has been removed allowing for improved visualization of prostate cancer (low T2 signal intensity white arrows) and the prostatic capsule (thin dark line encompassing the prostate, black arrow).

Metabolic Changes with Zonal Anatomy and Age

MRI/MRSI studies of the in situ human prostate have demonstrated significant metabolic changes with zonal anatomy, increasing age and pathology (cancer and BPH). The prostate is not a homogeneous organ but is composed of several anatomical zones that differ in morphology, function and pathologic significance [173]. MR images, particularly high-resolution endorectal T2-weighted images, provide an excellent depiction of prostate zonal anatomy with the peripheral zone demonstrating higher signal intensity than the central gland (transition, periurethral and central zones, Figure 8A) [120]. The peripheral zone is crescent shaped with a high ductal volume and is the site for approximately 68% of all prostate cancers [174]. High levels of citrate and intermediate levels of choline have been observed throughout the young (<40 years of age) healthy peripheral zone, and these levels do not change with increasing age (Figure 9) [36]. Unlike the normal peripheral zone, both citrate and choline levels change with increasing age in the central gland [36]. These changes are due to the development of benign prostatic hyperplasia of the central gland. Mean citrate levels in the hypertrophied central gland of older men (>40 years old) are significantly increased compared to the central gland of younger individuals (Figure 9) [36]. However, variation in the stromal and epithelial cell content of BPH results in a very wide range of citrate levels. These in vivo findings are consistent with previous high-resolution extract studies of BPH tissues. Schiebler et al. [148] and Costello and Franklin [152] found a roughly linear correlation between the percentage epithelial cell content and citrate levels observed in 1H spectra of extracts of BPH tissue.

Figure 8.

(A) A reception profile corrected axial FSE prostate image taken from the midgland of a patient with prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is anatomically identified as a region of low signal intensity in the right peripheral zone (white arrows) compared to the high signal intensity of the left peripheral zone (blackarrow). (B) Same image as in (A) with corresponding PRESS selected volume (thick solid white line) and a small section (6x6 voxels) of the phase encoded spectral array. (C) 0.24 cm3 proton spectra associated with the region of the prostate indicated by the phase encoded grid in (B). Prostate cancer can be metabolically identified as region of elevated choline and reduced citrate in the right peripheral zone compared to the healthy tissue (low choline and high citrate) in the left peripheral zone. (D) A (choline+creatine)/citrate peak area ratio image (red) overlaid on a the corresponding T2-weighted image. The (choline+creatine)/citrate peak area ratio has been thresholded such that all intensities below three standard deviations of the mean healthy peripheral zone value are translucent whereas those above the threshold demonstrate increasing intensities of red.

Figure 9.

Plot of individual (x's) and mean (circles) choline/normal peripheral zone choline (A) citrate/normal peripheral zone citrate (B) area ratios for the central gland, periurethral tissues, BPH and prostate cancer. (C) Plot of individual (x's) and mean (circles) (creatine+choline)/citrate area ratios for regions of prostate cancer, BPH, normal peripheral zone in young volunteers and patients. Note the absence of overlap of individual (choline+creatine)/citrate ratios between regions of normal peripheral zone (Pz) and prostate cancer. Also note that older individuals demonstrated peripheral zone ratios that were not different from the younger volunteer values. (From Ref. [36]; with permission.)

A mean threefold reduction in prostate citrate levels and a twofold elevation of prostate choline levels have been observed in regions of cancer relative to the normal peripheral zone (Figure 8C) [36]. These significant metabolic changes with prostate cancer are consistent with, but are more dramatic than changes reported by previous in vivo single-voxel 1H studies of prostate cancer [26,143–147]. This is most likely due to reduced partial volume averaging with surrounding normal tissue in the higher-resolution MRSI data (≈0.24 cm3) compared to the single-voxel data (≈1–6 cm3). In these studies, the peak area ratio of choline/citrate or the (choline+creatine)/citrate ratio have emerged as very specific markers for prostate cancer due to the opposite nature of the changes in choline and citrate that occur in regions of cancer [36]. The creatine peak area is often added into the ratio for robustness of quantification, because it is often difficult to resolve it from the choline resonance especially in normal tissue. The magnitude of the reduction in citrate and elevation in choline has been very variable leading to more than a 10-fold range of individual cancer (choline+creatine)/citrate peak area ratios [36]. Although there has been a wide range of (choline+creatine)/citrate ratios in cancer, there has been minimal overlap of (choline+creatine)/citrate peak area ratios between normal peripheral zone and cancer values (Figure 9) [36]. There was, however, significant overlap between (choline+creatine)/citrate ratios in regions of cancer and predominately stromal BPH. Predominately stromal BPH, like cancer, demonstrates low signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging, and low citrate levels giving rise to overlap between the pathologies.

MRSI and Cancer Aggressiveness

There is also evidence that the magnitude in choline elevation and citrate reduction is related to cancer aggressiveness. MRI/MRSI study of 26 patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer before radical prostatectomy and step-section pathologic examination has demonstrated a strong linear correlation between the decrease in citrate and the elevation of choline with Gleason grade, a pathologic measure of cancer aggressiveness [175] (Figure 10). To minimize the partial volume averaging with surrounding normal tissue in this study, spectroscopic voxels were shifted during post processing to be within the region of cancer as identified on pathology and T2-weighted imaging. There was a significant (P<.05) correlation of the elevation of choline and (choline+creatine)/citrate ratio, and reduction in citrate with cancer grade. These findings are consistent with early biochemical studies that have indicated that citrate levels in prostatic adenocarcinomas are grade dependent, with citrate levels being low in well differentiated prostatic cancer and effectively absent in poorly differentiated prostatic cancer [149,176,177]. Costello et al. [176] and Cornel et al. [135] found a correlation between citrate levels in extracted prostate cancer specimens with the percentage of acinar structures seen histologically.

Figure 10.

Representative 0.24 cm3 PRESS 1H spectra (TR-1 sec, TE-130 ms) “voxel shifted” to be within regions of cancer based on T2-weighted MRI and subsequent step-section histopathology of the surgically resected prostate. A region of Gleason Grade; (A) 5 (2+3), (B) 6 (3+3), (C) 7 (3+4), (D) 8 (4+4), and (E) metastatic prostate cancer in brain.

The in vivo (cancer choline)/(normal choline) ratio was found to be the most significant metabolic (P<.0001) discriminator of high (7+8) from low grade (5+6) cancers [178]. Increased choline and phosphorylcholine levels and choline kinase activity have been documented in many human cancers, including cancers of the brain, breast, liver, and colon [179–183]. Activation of the enzyme choline kinase leads to increased production of phosphorylcholine, a putative second messenger involved in cellular proliferation, in ras-oncogene transformed cells [163,165,184–190]. Furthermore, administration of choline kinase inhibitors have been found to lead to a profound inhibition of cellular proliferation [163,188]. These results support an important role of choline kinase and elevated choline and phosphocholine levels in cancer aggressiveness.

Although histologic scores will remain the standard for confirming the presence of prostate cancer and predicting biologic behavior, the potential of MRSI to provide similar information is very exciting. Due to the great heterogeneity of prostate cancers and biopsy sampling errors, cancers are often not detected or are inaccurately graded. In these cases, 3D MRSI might be valuable in providing an additional assessment of cellular function and organization, noninvasively and throughout the gland.

Improved Localization of Cancer

A recent MRI/MRSI study of 53 patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer before radical prostatectomy and step-section pathologic examination has demonstrated, that by combining the specificity of MRSI with the sensitivity of MRI, the ability to localize cancer to a sextant of the prostate can be significantly increased [191]. Receiver operating characteristic analysis showed significantly (P<.001) improved tumor localization when MR spectroscopic imaging was added to MR imaging (Figure 11). High specificity (up to 91%) was obtained when combined MR imaging and 3D MR spectroscopic imaging indicated cancer, whereas high sensitivity (up to 95%) was determined when either test provided a positive result.

Figure 11.

ROC curve comparing the diagnostic performance of MRI alone and combined with MRSI. The addition of MRSI improved the diagnostic performance of MRI in the localization of prostate cancer to a sextant of the prostate. (Adapted from Ref. [191] with permission.)

Postbiopsy hemorrhage represents a common impedance to the accurate detection of prostate cancer. It has been demonstrated that the staging accuracy of prostate cancer was significantly improved when MRI was deferred for 21 days following biopsy [118]. However, low or high signal intensity postbiopsy artifacts may persist for an indeterminate amount of time. The metabolic information provided by MRSI can help in the determination of whether tissues underlying a region of post biopsy hemorrhage are cancer. In a study of 175 patients with prostate cancer, who had evidence of postbiopsy hemorrhage, we found the addition of 3D MRSI to MRI resulted in a significant increase (P<.01) in accuracy (52.6% to 74.8%) and specificity (26.6% to 65.8%) of tumor detection over MRI alone [192].

There are several areas of prostate cancer management that benefit from improved localization of cancer within the prostate: 1) targeting TRUS guided biopsies for patients with prostatic specific antigen (PSA) levels indicative of cancer but negative previous biopsies (Figure 12); 2) better stratification of patients in clinical trials; 3) monitoring the progress of patients who select “watchful waiting” or other minimally aggressive cancer management options; 4) guiding and assessing emerging “focal” prostate cancer therapies.

Figure 12.

An axial T2-weighted images through the prostate of a patient who had significantly enlarged central gland due to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH, dashed arrow) and a compressed peripheral zone. Due to an elevated PSA (12 ng/ml), he underwent a TRUS guided biopsy that was negative. The sampling error of TRUS guided biopsy which is already large in the average-size gland is further increased in very large prostates. Prostate cancer was identified in a subsequent MRI/MRSI exam based on low signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (A, solid arrow), and by elevated choline and reduced citrate in the corresponding 0.24 cm3 array of proton spectra (C). A subsequent MRI/MRSI MR targeted, TRUS guided biopsy confirmed the presence of cancer in the right peripheral zone.

Improved Assessment of Extracapsular Spread of Cancer

Knowledge of the spread of cancer outside the prostate is critical for choosing an appropriate therapy. Patients with cancer that is localized within the prostate or has spread minimally beyond the capsule are candidates for local therapy, whereas those with greater cancer spread require systemic therapy or a combination of systemic and local therapy. Because prior histopathologic studies have demonstrated that prostate cancer volume is a significant predictor of extracapsular escape (ECE) of prostate cancer [174,193], tumor volume estimates based on MRSI findings [112] have been used in conjunction with high specificity MRI criteria [111] to diagnose ECE. A recent MRI/MRSI study of 53 patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer before radical prostatectomy and step-section pathologic examination has demonstrated that the addition of MRSI to MRI improves the accuracy of MRI in the diagnosis of ECE in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer (Figure 13) [112].

Figure 13.

ROC curve comparing the diagnostic performance of MRI alone and combined with MRSI. The addition of MRSI improved the diagnostic performance of MRI in the prediction of spread of cancer outside the prostate. (Adapted from Ref. [112] with permission.)

Follow-up After Therapy

After successful surgery or radiation therapy, serum levels of the prostate tissue marker, prostatic specific antigen (PSA), are often useful in predicting radiation failure [194,195]. However, PSA is not specific for cancer and can be elevated due to the presence of residual benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or normal prostatic tissues [194,195]. The accuracy of conventional radiologic techniques (TRUS, CT, MRI) for detecting residual/recurrent cancer is poor because most therapies induce tissue changes that mimic cancer [99,121,196]. The only definitive means of identifying residual or recurrent disease remains histologic analysis of ultrasound guided biopsy samples, which may be subject to large sampling errors.

Recent studies have indicated that residual or recurrent prostate cancer can be discriminated from normal and necrotic tissue after cryosurgery [169,171,172]. In a study of 25 patients before and after cryosurgery, histologically confirmed necrotic tissue (N=432 voxels) did not demonstrate any observable choline or citrate (Figure 14A). The (choline+creatine)/citrate ratio in regions of histologically confirmed benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH, 0.61±0.21, N=52 voxels, Figure 14B) and cancer (2.4±1.0, N=65 voxels, Figure 14C) after cryosurgery were not significantly different from those observed before therapy, but were significantly different from necrosis and each other.

Figure 14.

(A) Representative 0.24 cm3 PRESS 1H spectrum of necrosis and corresponding histologic slide of necrotic biopsy tissue. (B) Representative 1H spectrum of BPH and corresponding histologic slide of BPH biopsy tissue. (C) Representative 1H spectrum of prostate cancer and corresponding histologic slide of malignant biopsy tissue. (Adapted from Ref. [169].)

There is also evidence that the same is true for other therapies such as hormone ablation therapy [197,198], radiation therapy [199], and even for detection of residual cancer in the prostatic bed after radical prostatectomy [200]. Studies are currently under way investigating the accuracy of MRI/MRSI in assessing the presence and spatial extent of prostate cancer after these therapies, and the prognostic value of early metabolic changes. The detection of residual cancer at an early stage following treatment would allow earlier intervention with additional therapy, and provide a more quantitative assessment of therapeutic efficacy.

Conclusions

Proton MRSI studies of the brain and prostate have demonstrated the feasibility of noninvasively assessing human cancers based on metabolite levels before and after therapy in a clinically reasonable amount of time. In the brain, MRSI studies have demonstrated dramatic spectral differences between normal brain tissue (low choline and high NAA) and brain tumors (low NAA, high choline). The lower levels of NAA detected in brain tumors is presumably due to differences in cell type because NAA is found predominantly only in neurons. In the prostate, MRSI studies have demonstrated dramatic spectral differences between normal prostate tissue (low choline and high citrate) and prostate cancer (low citrate, high choline). The lower levels of citrate detected in prostate tumors is presumably due to a loss of glandular function (production of citrate) and the loss of characteristic ductal morphology (where citrate accumulates) in regions of cancer. The higher choline resonance observed in both brain and prostate tumors is probably due to altered membrane phospholipid metabolism, mobility, and composition. The presence of edema and necrosis in both the prostate and brain was reflected by a reduction of the intensity of all resonances due to reduced cell density. In all cases MRSI was still able to discriminate necrosis (absence of all metabolites, except lipids and lactate) from viable normal tissue and cancer.

The results of current MRSI studies provide compelling evidence for the discrimination of solid tumor, viable brain and prostate, and necrotic tissues based on cellular metabolite levels. When combined with volumetric MR images, it is possible to obtain an anatomic and metabolic picture of the tumor and surrounding tissue in response to therapy. Further studies are needed to determine the sensitivity and specificity of MR parameters as predictors of treatment outcome, but initial studies have been very exciting. The concept of combining MRI and MRS techniques within a single examination is particularly attractive because it reflects the extension of an existing diagnostic test rather than the introduction of expensive new technology. We therefore see the role of MRSI as being part of an integrated clinical examination which is routinely performed in follow-up of patients with brain and prostate tumors. Quantitative analysis of both the MRI and MRS lesions would provide an objective basis for assessing disease progression or response to therapy. This capability is expected to have a major impact on patient care by providing a basis for classifying tumors based on their functional characteristics, predicting which treatments will be effective for a particular patient and understanding the reasons for success or failure of new therapies.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ryan Males, Mark Swanson, Khanh Tran, Tracy McKnight, Sue Noworolski, Ted Graves, Roland Henry, Mark Day, Lucas Carvajal, Larry Wald, Josh Star-Lack, Evelyn Proctor. Gary Ciciriello, and Niles Bruce for their contribution to the human MRI/MRSI studies. We also acknowledge the technical support of Ralph Hurd, Tom Raidy, Pom Salisuta, Jim Tropp, and Ann Shimakawa from General Electric.

Abbreviations

- MRSI

magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- CHESS

chemical shift selective suppression

- STIR

short-time inversion recovery

- BASING

band selective inversion with gradient dephasing

- SLR

Shinnar-Le Roux

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- VSS

very selective suppression (pulses)

- PRESS

point resolved spectroscopy

- STEAM

stimulated echo acquisition mode spectroscopy

- CSI

chemical shift imaging

- CC/C

choline + creatine/citrate (ratio)

- TRUS

transrectal ultrasound

- FDG-PET

fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- rCBV

regional cerebral blood volume

Footnotes

This research was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health grants CA59897, CA64667, CA79980, CA59880, and CA57236, and the American Cancer Society grants RPG-96-146, EDT-117, and EDT-34, and research awards from the CaP CURE Foundation

References

- 1.Arnold DL, Shoubridge EA, Feindel W, Villemure JG. Metabolic changes in cerebral gliomas within hours of treatment with intra-arterial BCNU demonstrated by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]