Abstract

We have identified a conditional mutation in the shared Rpb6 subunit, assembled in RNA polymerases I, II, and III, that illuminated a new role that is independent of its assembly function. RNA polymerase II and III activities were significantly reduced in mutant cells before and after the shift to nonpermissive temperature. In contrast, RNA polymerase I was marginally affected. Although the Rpb6 mutant strain contained two mutations (P75S and Q100R), the majority of growth and transcription defects originated from substitution of an amino acid nearly identical in all eukaryotic counterparts as well as bacterial ω subunits (Q100R). Purification of mutant RNA polymerase II revealed that two subunits, Rpb4 and Rpb7, are selectively lost in mutant cells. Rpb4 and Rpb7 are present at substoichiometric levels, form a dissociable subcomplex, are required for RNA polymerase II activity at high temperatures, and have been implicated in the regulation of enzyme activity. Interaction experiments support a direct association between the Rpb6 and Rpb4 subunits, indicating that Rpb6 is one point of contact between the Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex and RNA polymerase II. The association of Rpb4/Rpb7 with Rpb6 suggests that analogous subunits of each RNA polymerase impart class-specific functions through a conserved core subunit.

Synthesis of mRNA catalyzed by RNA polymerase (RNAP) II in eukaryotes is an intricately regulated process that involves the coordinate action of numerous regulatory proteins and protein complexes. Chromatin remodeling, histone modifications, and repressors, activators, and coactivator complexes collaborate in the recruitment of the general transcription factors and RNAP II in response to cellular signals (37, 38, 53, 56). RNAP II is a 12-subunit enzyme whose sequence, architecture, and function are strikingly conserved from lower to higher eukaryotes. RNAP II is well characterized in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and its subunits are referred to as Rpb1 to Rpb12 (genes are designated RPB1 to RPB12). Rpb1, Rpb2, Rpb3, and Rpb6 are relatives of the bacterial β′, β, α, and ω subunits, respectively (32, 47, 53).

Rpb6 (also known as ABC23) is a 155-amino acid, 18-kDa subunit that belongs to a subset of five subunits referred to as the “common subunits.” Rpb6, along with Rpb5, Rpb8, Rpb10, and Rpb12, are assembled into RNAPs I, II, and III. The function of Rpb6 is conserved; it can be replaced with its human counterpart in vivo (31). The solution structure of human Rpb6 determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy was the first to correlate regions of high sequence conservation to discrete structural domains (12). High-resolution atomic structures of S. cerevisiae containing Rpb6 followed, allowing the identification of Rpb6 in context with the majority of RNAP II subunits (9, 10, 15). Rpb6 is in proximity to a flexible module containing portions of Rpb1 and Rpb2 called the clamp. The clamp pivots over the active center with a fixed range of motion that appears to enable both open and closed positions that alter the size of the DNA binding cleft.

Rpb6 is one of two RNAP II subunits (along with the Rpb1 subunit predominantly phosphorylated at its carboxy-terminal domain [CTD]) that are phosphorylated (22, 25). Unlike in the case of the well-studied Rpb1 CTD, the biological significance of this modification in Rpb6 is unknown. Interestingly, Rpb6 is positioned at the base of the clamp near a series of switches that control clamp movement (10). The open clamp is thought to allow entry of the promoter DNA. The closed clamp is proposed to sense the conformation of the DNA-RNA hybrid and separate the DNA and RNA strands upstream of the transcription bubble. Rpb6 phosphorylation may influence the position of the clamp and thus the activity of the enzyme.

Despite sharing only limited sequence similarity, the Rpb6 and ω subunits possess significant structural and functional similarities (32). Rpb6 and ω also occupy comparable positions within their respective X-ray crystal structures (11, 36, 55). Both subunits wrap around portions of the largest subunit (β′ or Rpb1) to promote subunit assembly and stability (32). This is in agreement with the results of previous work indicating a role for Rpb6 in assembly (39) and a role for ω in optimal enzyme activity and stability in enzyme reconstitution experiments (35). Rpb6 and ω are proposed to latch the NH2- and COOH-terminal regions of Rpb1 or β′ together, facilitating the stable assembly of the remaining RNAP II or RNAP subunits, respectively (32). Since the largest subunits of all three eukaryotic RNAPs are related in sequence, Rpb6 may also have a similar stabilizing role in RNAPs I and III that has yet to be demonstrated. Since high-resolution atomic structures of RNAPs I and III are not yet available, the precise subunit-subunit contacts in these enzymes are not known.

Rpb6 has also been linked to transcription elongation. Some temperature-sensitive mutants in Schizosaccharomyces pombe are unable to grow in the presence of 6-azauracil (19), a phenotype often associated with defects in elongation (17). A functional and direct physical interaction between TFIIS and Rpb6 was subsequently demonstrated (19). TFIIS and Rpb9 enhance elongation efficiency by facilitating transcription through DNA arrest sites (which cause RNAP II to pause or arrest mRNA synthesis) (2).

Finally, the archaebacterial TFIIB and Rpb6 counterparts have recently been demonstrated to interact in vitro (29). Although an interaction between eukaryotic Rpb6 and TFIIB has not yet been uncovered, TFIIB does directly interact with RNAP II (16). Also, the general position of TFIIB derived from low-resolution structures indicates proximity to Rpb6 (27). Therefore, an interaction between TFIIB and Rpb6 is possible.

In this work, we characterized the effects of a conditional mutation in a highly conserved residue of Rpb6. Although the mutated form of Rpb6 was assembled in each of the three RNAPs, its effect on enzyme activity was variable. RNAP I activity was only marginally altered, while RNAP II and RNAP III activities were severely impaired. RNAP II purified from the Rpb6 mutant lacked the subunits forming the dissociable Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex at both permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. In vivo interaction experiments support a direct association between Rpb6 and the Rpb4 subunit of the Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

The yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Liquid cultures were grown in synthetic complete (SC) or yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium as indicated (49). Growth curves were determined in SC-Leu medium and started at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.08, and cell density was measured at intervals for up to 24 h. The working concentration of 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) used in plasmid shuffle experiments was 1 mg/ml (3).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description |

|---|---|

| Strains | |

| N222 | MATα ura3-52 hisΔ200 leu2-3,112 lysΔ201 ade2 |

| WY37 | MATα ura3-52 hisΔ200 leu2-3,112 lysΔ201 ade2 RPB6Δ::HIS3 [pRP623] |

| WY202 | MATα ura3-52 hisΔ200 leu2-3,112 lysΔ201 ade2 RPB6Δ::HIS3 [pRP665] |

| WY203 | MATα ura3-52 hisΔ200 leu2-3,112 lysΔ201 ade2 RPB6Δ::HIS3 [pRP673] |

| WY204 | MATα ura3-52 hisΔ200 leu2-3,112 lysΔ201 ade2 RPB6Δ::HIS3 [pRP674] |

| SHY407B | MATα ade2Δ hisΔ200 leuΔ0 met15Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 RPB9-Flag-TAP (TRP1) |

| WY205 | MATα ade2Δ hisΔ200 leuΔ0 met15Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 RPB9-Flag-TAP (TRP1) RPB6Δ::HIS3[pRP665] |

| Plasmids | |

| pRP623 | BamHI/HindIII PCR fragment containing the RPB6 open reading frame plus 234-bp promoter sequence in pRS416 (URA3 CEN) |

| pRP665 | rpb6-151 allele in BamHI/HindIII fragment containing the RPB6 open reading frame plus 234-bp promoter in pRS415 (LEU2 CEN) |

| pRP673 | pRP665 with RPB6 open reading frame encoding Rpb6(S75S) |

| pRP674 | pRP665 with RPB6 open reading frame encoding Rpb6(Q100R) |

| pRP671 | rpb6-151 allele in pACT2-1 two-hybrid vector |

| pRP669 | RPB6 in pACT2-1 two-hybrid vector |

| pRP416 | RPB4 in pAS2-1 two-hybrid vector |

| pRP739 | RPB7 in pACT2 two-hybrid vector |

| pRP740 | RPB7 in pAS2-1 two-hybrid vector |

Isolation of Rpb6 mutants.

The rpb6-151 allele was isolated after PCR mutagenesis (34). WY-37 was transformed with PCR-mutagenized plasmid DNA, and transformants were then grown on 5-FOA and tested for growth at either high (37 or 38°C) or low (12 or 15°C) temperature. Plasmids were isolated from the mutants exhibiting the strongest conditional phenotypes. Each was reintroduced into WY-37 to confirm the original growth phenotypes after 5-FOA treatment. The RPB6 coding region was sequenced in the mutants exhibiting the strongest growth phenotypes. The Rpb6(Q100R) and Rpb6(P75S) mutants were created by site-directed PCR mutagenesis (18) and transformed into WY-37. Transformants were subjected to 5-FOA selection and tested for growth at 12, 30, and 37°C. Structures highlighting the positions of the two Rpb6 mutations were created and analyzed by Richard Ebright using DS ViewerPro by Accelrys.

Transcription extract preparation and in vitro transcription assays.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from isogenic wild-type and mutant cells according to published procedures (52). Yeast cells were grown in YPD medium to an OD600 of 3. The final extract was dialyzed until the conductivity of a 1:200 dilution was below 100 μS/cm. The protein concentration was measured, and the extract was stored at −70°C. Two independently prepared extracts for wild-type and mutant strains were used for the in vitro transcription assays to ensure reproducibility.

The RNAP II activity of the whole-cell extracts was measured by both promoter-dependent and -independent transcription assays (28). For promoter-independent transcription, denatured salmon sperm DNA was used as the template and reactions were carried out with or without the RNAP inhibitor α-amanitin added to a concentration effective for specific inhibition of RNAP II synthesis (50 μg/ml). For promoter-dependent transcription, the template plasmid used for the transcription reactions, pGAL4CG−, contained a hybrid promoter consisting of a single Gal4-binding site and a CYC1 TATA element that drives synthesis of two predominant ∼350-nucleotide transcripts from a G-less cassette template. Omission of GTP during the reaction and subsequent treatment with RNase T1 significantly increased the signal by digestion of nonspecific transcripts. The activator used was pure, recombinant Gal4-VP16. Transcription reactions contained 300 μg of extract and 200 ng of template. Reactions for both assays were performed in triplicate.

Measurement of total poly(A) RNA levels and Northern analysis.

RNA was prepared from samples harvested at intervals after a temperature shift to 37°C from cells grown in SC-Leu medium (wild-type cells were transformed with YEplac111). Duplicates containing 40 μg of total RNA per sample were immobilized to nitrocellulose and hybridized with an excess of radioactively labeled (poly)dT oligonucleotide. Band intensities were quantified using a phosphorimager.

Twenty micrograms of total RNA was subjected to Northern analysis to determine the steady-state levels of specific mRNAs. The following restriction fragments were used for radioactively labeled hybridization probes: PGK1, 0.72-kb BamHI/EcoRI; U3, 0.5-kb BamHI/HpaI; and RPL3 (TCM1), 0.75-kb BglII/XbaI.

β-galactosidase assays to measure activation.

The LACZ reporter plasmids pJH359, pLGSD5, and pN703, containing a CYC1 TATA element and the INO1, GAL1, or PHO5 upstream activation sequence (UAS) element, respectively, were separately transformed into wild-type or mutant cells. To quantify activation at the INO1 UAS by Ino2, cells were grown at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase in minimal medium containing 400 μM inositol. Cells were washed, followed by incubation with agitation for 10 h in the minimal medium containing 10 μM inositol. For analysis of activation at the GAL1 UAS by Gal4, cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C in SC medium containing 2% raffinose, collected by centrifugation, washed, and then incubated for 3 h at 30°C in SC medium containing 5% galactose. For PHO5, cells were grown at 30°C in either low-phosphate (inducing) or high-phosphate (noninducing) YPD medium. Cultures were started at an OD600 of 0.01 and harvested at an OD600 of approximately 0.5. For low- and high-phosphate YPD media, potassium phosphate was added to final concentrations of 0.1 and 7.5 mM, respectively. Cells were harvested, extracts were prepared, enzyme levels were assayed, and unit calculations were performed according to standard methods (4).

Quantification of newly synthesized RNAP I and RNAP III transcripts.

Levels of newly synthesized RNAP I and III transcripts were measured using oligonucleotides complementary to the junction of mature and processed RNA species: tryptophan tRNA (tRNAw) for RNAP III (see Fig. 5) (7) or the 25S rRNA precursor for RNAP I (see Fig. 6). Detailed methods for the S1 nuclease digestion experiments using these oligonucleotides plus equivalent amounts of total RNA (total RNA samples were the same as those used for quantification of mRNA) have been described previously (33).

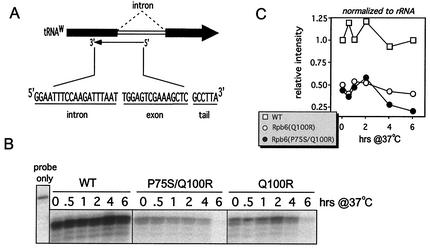

FIG. 5.

Assessment of RNAP III activity. (A) tRNAw oligonucleotide sequence, components, and approximate annealing location. (B) S1 analysis of total RNA harvested at the time points indicated after a 37°C temperature shift using the probe shown in panel A. The probe-only control demonstrated that the S1 treatment was effective, since the 6-nucleotide tail was cleaved from digested samples. (C) Band intensities in panel B were quantified and normalized to the wild-type (WT) 0-h time point, followed by a final normalization step to rRNA levels (as measured in Fig. 6).

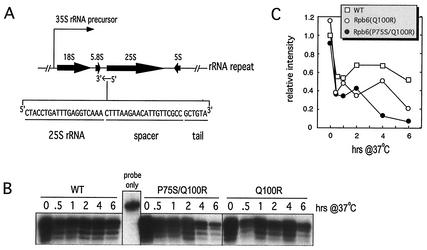

FIG. 6.

Assessment of RNAP I activity. (A) 25S rRNA oligonucleotide sequence, components, and approximate annealing location. (B) S1 analysis of total RNA harvested at the time points after a 37°C temperature shift using the probe shown in panel A. The probe-only control demonstrated that the S1 treatment was effective, since the 6-nucleotide tail was cleaved from digested samples. (C) Band intensities in panel B were quantified and normalized to the wild-type (WT) 0-h time point.

Purification of RNAP II.

We used the tandem affinity purification (TAP) method (42, 43) to isolate RNAP II. We first transformed either the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) or Rpb6(Q100R) plasmid into an Rpb9-TAP-tagged strain (kindly provided by the laboratory of Steve Hahn), followed by deletion of the chromosomal copy of RPB6. After confirmation of the constructed strain by Southern analysis and the presence of a conditional phenotype, we prepared a whole-cell extract (described above) from the mutant and isogenic wild-type TAP-tagged strains. We then followed a purification protocol available online (http://www-db.embl-heidelberg.de/jss/servlet/de.embl.bk.wwwTools.GroupLeftEMBL/ExternalInfo/seraphin/TAPpurification.html). Calmodulin beads were purchased from Stratagene, recombinant TEV protease was obtained from Invitrogen, and immunoglobulin G Sepharose 6 Fast Flow was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. Purified protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized by silver stain.

Protein interaction studies.

The Matchmaker two-hybrid system (Clontech) was used as a source of plasmids and yeast strains. Detailed protocols for the procedures used can be found in the downloadable yeast protocols handbook at the company website (www.clontech.com). pAS2-1 was used to express a GAL4 DNA binding domain-Rpb4 fusion protein. pACT2 was used to express the GAL4 activation domain fused to the coding region of either wild-type Rpb6 or Rpb6(P75S/Q100R). Various other combinations of GAL4 activation domain-GAL4 DNA binding domain plasmid pairs (e.g., Rpb4-Rpb7 and Rpb6-Rpb7) were transformed into pJ69-4A yeast cells (20) expressing a GAL1-lacZ reporter plasmid, as well as the pVA3-pTD1 positive control plasmid pair and all negative control combinations. Interactions were assessed after quantification of β-galactosidase activity (normalized to protein concentration) derived from individual transformants by using the liquid culture assay (with o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside [ONPG] as the substrate). All samples were tested in triplicate, with each sample in a set being derived from separate transformants.

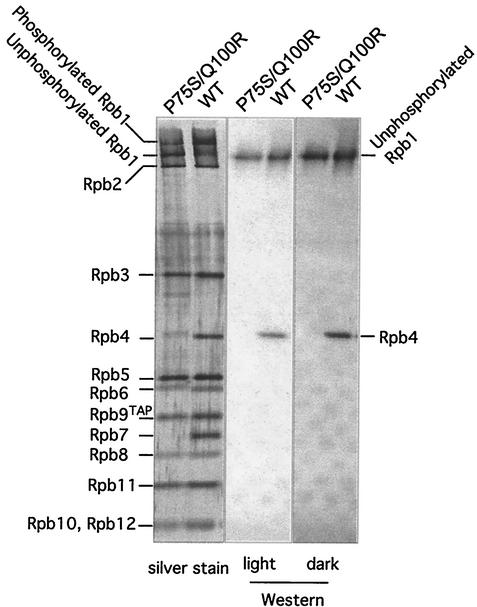

Monoclonal antibodies to Rpb1 CTD (8WG16) and Rpb4 (Neoclone) were used for Western analysis (Fig. 7). The 8WG16 monoclonal antibody (48) preferentially recognizes the unphosphorylated form of the CTD (5).

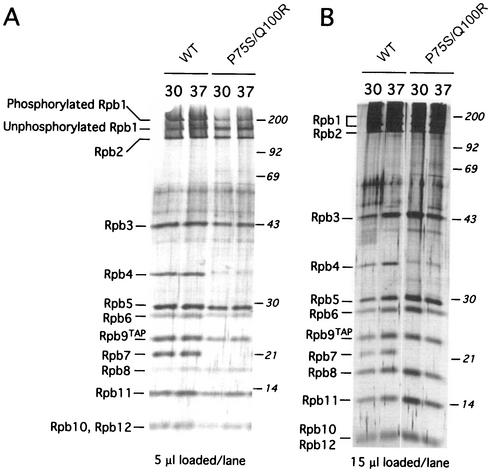

FIG. 7.

Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) is not generally defective in assembly but lacks Rpb4 and Rpb7. (A) Equivalent volumes of final purified product (amounts shown below each panel) derived from equal numbers of yeast cells harvested before and after a 2-h shift to 37°C were loaded in each lane. Molecular-weight markers are shown on the right, and positions of RNAP II subunits are shown on the left. WT, wild type. (B) Equivalent amounts of purified product were loaded in excess to clearly demonstrate the absence of the Rpb4 and Rpb7 bands.

RESULTS

Identification of an Rpb6 conditional mutant in a conserved domain that exhibits transcriptional defects.

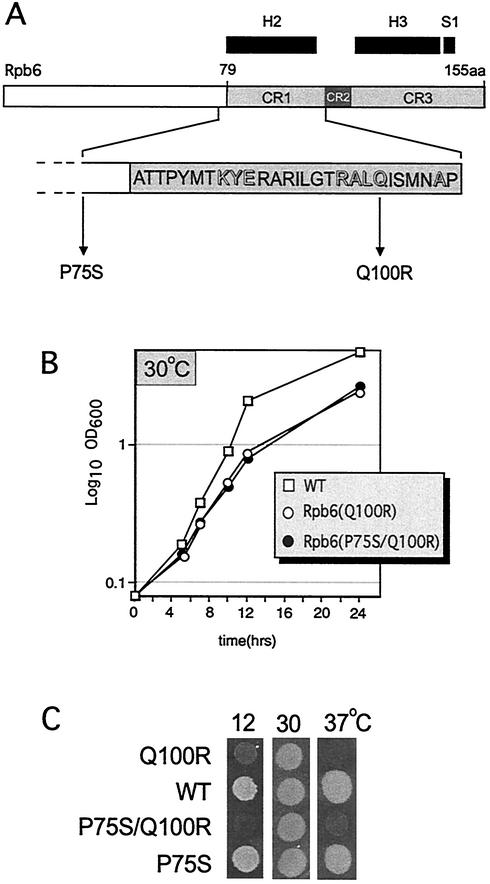

The carboxy-terminal half of Rpb6 is highly conserved among all eukaryotes (e.g., over 90% of the residues between human and S. cerevisiae are identical or similar). However, once archaeal and bacterial subunits are added to the alignment, the regions of conservation (based on a combination of structural and sequence similarity) are distilled to three discrete regions designated CR1, CR2, and CR3 (32). Only about one-third of the amino acids comprising CR1, CR2, and CR3 exhibit strong conservation among all species. We identified one conditional mutant, rpb6-151, from our collection of sequenced RPB6 conditional mutations worth pursuing in further detail, since it possessed a mutation in CR1 and exhibited a defect in transcription.

rpb6-151 cells were cold sensitive and temperature sensitive (Fig. 1C). This mutant allele carried two mutations in RPB6: one in the helix 2 region of CR1 (Q100R) and the other outside of CR1 (P75S) (Fig. 1A). To determine whether both of the mutations contributed to the defects in growth and transcription, we constructed strains that expressed each mutation in isolation. Only the Rpb6 Q100R mutation in CR1 reconstituted the growth phenotype (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the Rpb6(P75S) cells were able to grow at high and low temperatures. At permissive temperature, Rpb6(Q100R) and Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) cells behaved in a similar manner: each grew more slowly than did wild-type cells (exhibiting estimated doubling times of 3 h instead of 2 h [Fig. 1B]).

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of rpb6-151. (A) Bar diagram of S. cerevisiae Rpb6. The three regions in the Rpb6 carboxy-terminal half (CR1, CR2, and CR3) displaying significant sequence similarity between all Rpb6 counterparts are delineated (gray boxes); regions of defined secondary structure (helices 2 and 3 and strand 1) are shown at top (black boxes). The complete sequence of CR1 is shown, with residues that are identical in nearly all Rpb6-related proteins in bacteria, archaebacteria, and eukaryotes highlighted (adapted from reference 32). The two amino acids mutated in rpb6-151 cells are also shown. (B) Growth curve of mutant and isogenic wild-type (WT) strains at the permissive temperature (30°C) (C) Equivalent amounts of mutant and wild-type cells were spotted onto YPD medium and incubated at the temperatures indicated.

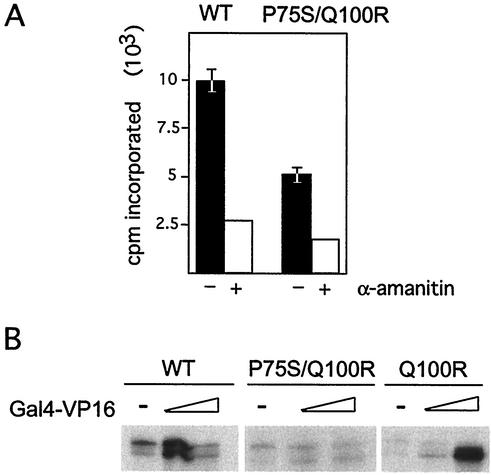

To measure transcription competence, we prepared whole-cell extracts from mutant [Rpb6(Q100R) as well as the original Rpb6(P75S/Q100R)] and isogenic wild-type strains. In a rough measurement of transcription levels supported by the original mutant, we detected a 50% decrease in activity by the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) extract in a promoter-independent assay (Fig. 2A). Using a more precise promoter-dependent assay, we found that mutant extracts supported a lower level of basal transcription initiation relative to wild-type cells. However, Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) extracts failed to respond to activation by Gal4-VP16 at low or high concentrations (enough to cause a squelching effect with wild-type extracts), while Rpb6(Q100R) extracts responded to the activator at the higher concentration only (Fig. 2B). In both assays, the deficiencies were apparent without preheating the extract or performing the transcription reaction at higher temperatures, indicative of a strong effect on transcription. In contrast, visualization of defects in transcription caused by conditional mutants in other components of the transcription machinery often requires one of these manipulations to detect transcriptional deficiencies (26).

FIG. 2.

Transcription defects in rpb6-151 cell extracts. (A) Mutant extracts have reduced activity in a promoter-independent transcription assay. Equivalent amounts of extracts were assayed for transcription on a denatured salmon sperm DNA template in the absence (−) or presence (+) of α-amanitin. Samples without α-amanitin were tested in triplicate and averaged. (B) Mutant extracts support reduced basal activity and are defective for activation in a promoter-dependent transcription assay. Shown are transcription products from wild-type (WT) and mutant whole-cell extracts with small or large amounts of Gal4-VP16 (elongated triangle) or without Gal4-VP16 (−) included in the transcription reaction. All transcription reactions used equal concentrations (300 mg) of whole-cell extracts from wild-type and mutant cells and 300 μg of template. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the mutant phenotype was confirmed with two independently purified whole-cell extracts.

mRNA levels are significantly reduced in both Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) and Rpb6(Q100R) mutants.

To compare the effects of the mutations on transcription in vivo, we prepared total RNA from Rpb6(P75S/Q100R), Rpb6(Q100R), or isogenic wild-type cells harvested at permissive temperature or at intervals after a shift to 37°C. We then used this RNA in assays designed to evaluate the activity of RNAP I, II, or III in mutant cells.

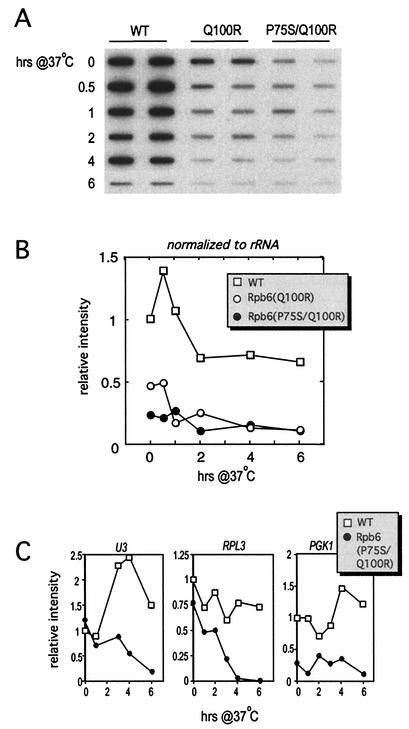

We first quantified steady-state mRNA levels to estimate RNAP II activity. Equivalent amounts of total RNA were immobilized to a filter and hybridized to radioactively labeled oligo(dT). mRNA levels decreased significantly after the temperature shift in both mutants (Fig. 3A and B). Eventually, steady-state mRNA levels began to decrease in the wild-type strain since the nonpermissive temperature is at the upper limit for growth in this genetic background. Although profiles from both mutants were nearly identical after the temperature shift, they displayed differences in the amount of steady-state mRNA present at late logarithmic phase at permissive temperature (Fig. 3A and B, 0-h time points). Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) and Rpb6(Q100R) possessed only 30 and 50% of wild-type mRNA levels, respectively. The lower steady-state mRNA levels for both mutant cells likely contributed to their lower growth rate at normal temperature (Fig. 1B). The difference in activities before the temperature shift is also consistent with the differences noted in the promoter-dependent transcription assay and indicates that both the double and single mutants are significantly impaired for transcription by RNAP II in vivo.

FIG. 3.

mRNA levels are significantly reduced in both Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) and Rpb6(Q100R) mutants. (A) Steady-state mRNA levels were assessed upon hybridization of radioactively labeled poly(dT)30 to 20 μg of immobilized total RNA prepared from wild-type (WT) and Rpb6 mutant cells harvested in increments after a 37°C temperature shift. (B) Band intensities in panel A were quantified and normalized to the WT 0-h time point, followed by a final normalization step to rRNA levels (as measured in Fig. 6). (C) Quantification of selected mRNA transcripts. Ten micrograms of total RNA was loaded into each lane, subjected to Northern analysis, and hybridized to the indicated DNA probes. Graphs represent quantified data from Northern analysis, with normalization to the respective 0-h time point.

We also measured the steady-state levels of three mRNA transcripts involved in different processes: ribosomal protein L3 (RPL3), snoRNA U3 gene SNR17A, and phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1). All three transcripts steadily decreased in abundance after the temperature shift (Fig. 3C). The cumulative results demonstrate that the Q100R mutation accounts for the growth and most of the transcription defects attributed to the original rpb6-151 allele possessing P75S and Q100R mutations. However, the P75S mutation is not inconsequential; it contributes to the overall transcription phenotype of the mutant.

Activation is not generally defective in Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) cells.

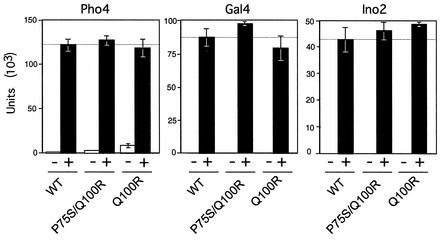

Since a defect in activation was noted in vitro, we wanted to assess the effects of the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) mutant on activator-dependent transcription in vivo. We tested activator function by measuring expression levels of a reporter gene driven by an inducible promoter containing a UAS element bound by Gal4, Pho4, or Ino2, which activates the GAL1 to GAL10, PHO5, or INO1 gene, respectively (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Activation is not generally defective in Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) cells. Assays were performed on extracts prepared from cells harvested after growth under activating (+) or nonactivating (−) conditions. The activator whose function was tested is designated above each diagram. Values are expressed as nanomoles of ONPG cleaved per minute per milligram of protein.

Wild-type and Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) cells containing the reporter plasmid for measuring activation were grown at the permissive temperature under nonactivating or activating conditions. β-Galactosidase activity measured in extracts prepared from each strain revealed levels of activation in the mutants that were equivalent to those in the control. Our results indicated that the mutant was not generally impaired for activation and suggests that the effects seen in vitro are likely to be indirect.

Mutation in a common subunit causes severe defects in transcription by two of the three RNAPs.

In contrast to mRNA transcripts, which have relatively short half-lives, tRNAs and rRNAs are extremely stable. Therefore, quantification of steady-state levels of any given rRNA or tRNA is not an accurate barometer of changes in RNAP I or III activity. Instead, we employed an assay designed to measure only new RNA synthesis in living cells. After annealing of the radioactively labeled oligonucleotide to RNA, the reactions were treated with S1 nuclease and the products (along with appropriate controls) were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

To assess RNAP III activity, we measured the levels of a newly synthesized tRNA by using an oligonucleotide probe that is complementary to an intron-exon junction of a rapidly processed yeast tRNA (Fig. 5A). Our study followed the synthesis of tRNAw in mutant and wild-type cells (7). New synthesis of tRNAw was significantly reduced in both mutants before and after the temperature shift (Fig. 5B and C). As was the case with our measurements of steady-state mRNA, the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) and Rpb6(Q100R) mutant cells behaved similarly in this analysis. Another parallel between RNAP II and III was the obvious deficiency in RNAP III activity even before exposure to nonpermissive conditions; both mutants showed an approximately 50% reduction in RNAP III activity at permissive temperature. All time points after the shift revealed a progressive decrease in tRNAw.

RNAP I transcript levels were measured by using a 35S rRNA precursor oligonucleotide that was complementary to the junction of the rapidly processed spacer between the 5.8S and 25S rRNA transcripts and the 5′ end of the 25S rRNA transcript (Fig. 6A). After the temperature shift, both wild-type and mutant RNAP I transcription decreased. However, after 1 h the wild-type RNAP I activity began to rebound. In contrast, RNAP I activity decreased gradually in both mutants (Fig. 6B and C). The decrease in RNAP I synthesis beyond the 2-h time point, which corresponded to very low steady-state mRNA levels, may be due to an indirect effect caused by the stringent response (51). This response is triggered by amino acid deprivation, indirectly in this case, due to the severe reduction in expression of amino acid genes and of genes encoding components of amino acid synthetic pathways, that leads to reduced synthesis of ribosomal proteins and rRNA. Whether the late decrease in rRNA synthesis originates directly from the mutant form of RNAP I containing Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) or indirectly from the stringent response, the effect on RNAP I is distinct from that on RNAP II and III.

RNAP II containing Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) lacks the Rpb4/Rpb7 subunit pair.

We purified RNAP II from the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) mutant and wild-type cells before and after a 2-h temperature shift to nonpermissive temperature. Remarkably, a dissociable subcomplex uniquely assembled into RNAP II, Rpb4/Rpb7, no longer associates with RNAP II both before and after the shift (Fig. 7). The amount of each of the remaining subunits in the mutant RNAP II was comparable to that seen with wild-type cells. Thus, there was no apparent defect in the Rpb6-Rpb1 interaction leading to defective assembly and destabilization of the RNAP II complex, as seen in another Rpb6(E144K) mutant (39). Although there is a band present near the position of Rpb4 with distinctly slower mobility, this band does not appear to be Rpb4. First, Rpb7 is clearly absent; the association of Rpb7 with the enzyme appears to occur predominantly through Rpb4 (8, 14, 25; our data in the following section). Second, the slower mobility is not associated with phosphorylation since only Rpb1 and Rpb6 have been demonstrated to possess this modification. Finally, Western blot analysis using an Rpb4 monoclonal antibody revealed the presence of an Rpb4 band in wild-type, but not mutant, RNAP II preparations (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Rpb4 is absent in Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) cells. Western analysis of mutant and wild-type (WT) samples used monoclonal antibodies to the unphosphorylated form of the CTD and to Rpb4. A silver stain of comparable samples used for Western analysis is shown on the left.

Rpb6 interacts with Rpb4 but not Rpb7.

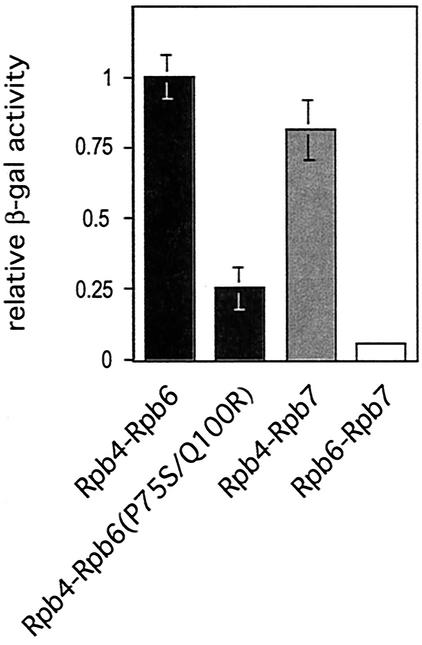

We used a two-hybrid approach to test whether the interaction between Rpb6 and the Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex is direct and, if so, to determine which subunit(s) interacts with Rpb6. To quantify the degree of the interaction, we measured relative β-galactosidase activities in extracts prepared from cells grown in liquid culture. Along with appropriate positive and negative controls, we tested for physical interactions between Rpb4 and either wild-type Rpb6 or Rpb6(P75S/Q100R), between Rpb7 and Rpb6, and between Rpb4 and Rpb7 (as another positive control). We documented an interaction between Rpb4 and Rpb6 (that appeared stronger than that between Rpb4 and Rpb7) but found little measurable interaction between Rpb7 and Rpb6 (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Two-hybrid analysis. Four independent experiments were performed; activities derived for interaction pairs in all four experiments were then normalized to that of the Rpb4-Rpb6 wild-type sample, averaged, and plotted as shown.

Rpb4 and Rpb7 tend to dissociate from the purified enzyme under mild denaturing conditions, native gel electrophoresis, and upon anion exchange chromatography (13, 45). Our data support the results of previous studies implicating Rpb4 as the subunit which directly contacts RNAP II (14, 25) and are consistent with the recently refined 12-subunit RNAP II structure (8). This structure revealed that the interaction of the Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex with the remainder of RNAP II occurs predominantly through Rpb4.

In agreement with the results of our RNAP II purification experiment, the interaction between Rpb4 and Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) was significantly reduced (to 25% of wild type). Although the Rpb6 mutations did not completely abolish the association between these two subunits in living cells, the interaction was not stable enough to survive biochemical purification steps. The growth phenotype of our mutant cells (Fig. 1C) is consistent with the existence of some association of Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) with Rpb4. Strains lacking the RPB4 gene (and thus the stable association of an Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex with RNAP II) are temperature sensitive at 32 to 34°C (depending on strain background), not 37°C as with the Rpb6(P75S/Q100R) mutant (54).

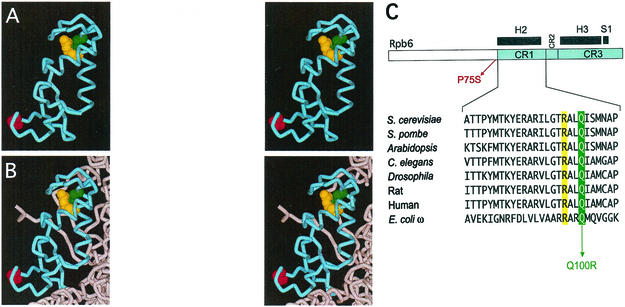

The Q100R mutation may alter the conformation of Rpb6.

We mapped the location of the two Rpb6 mutations in the atomic structure of RNAP II lacking Rpb4 and Rpb7 (Fig. 10). P75 was not in proximity to Q100 (Fig. 10A and B). Therefore, the two residues most likely do not function cooperatively and the subtle defects on transcription caused by the P75S mutation are mechanistically independent of those caused by Q100R. Since the Q100R mutation alone recapitulated the growth phenotype of the original rpb6-151 Q100R/P75S mutant and nearly the same level of transcription deficiencies, its integrity is important. Nearly all Rpb6 counterparts in archaebacteria, bacteria, and eukaryotes have a glutamine residue at this position.

FIG. 10.

Localization of Rpb6 Q100, R97, and P75. Panels A and B (courtesy of R. Ebright, Rutgers University, Piscataway, N.J.) represent stereo pairs to enable three-dimensional viewing. (A) Structure of the conserved Rpb6 carboxy-terminal half highlighting the positions of Q100 (green), R97 (yellow), and P75 (red) displayed in Cα plus side-chain format. The structure of the amino-terminal half of Rpb6 is disordered and not included in high-resolution crystal structures derived from Protein Data Bank structure no. 1I50. (B) Rpb6 carboxy-terminal half (blue) and portions of Rpb1 (gray) represented as ribbon diagrams (also from Protein Data Bank structure no. 1I50); residues Q100, R97, and P75 are shown as in panel A. (C) Alignment of Rpb6 CR1 from an array of eukaryotes plus the Escherichia coli ω subunit. The positions of the two mutations plus R97 are highlighted in colors analogous to those used in panels A and B. Alignments are adapted from reference 32.

The residues in contact with Q100 were examined, and three important points resulted from this analysis. (i) Q100 of Rpb6 does not contact Rpb1; the region of Rpb6 analogous to the region of ω that interacts with Rpb1 is on the side of Rpb6 opposite that of Q100. (ii) The position of Q100R would allow for interaction with Rpb4/Rpb7 based on the most recent estimates of Rpb4/Rpb7 placement in RNAP II (8). (iii) Q100 interacts with R97 through a hydrogen bond; R97 is completely buried in a hydrophobic region. Since charged residues prefer to reside on the surface of a protein, this buried arginine needs its hydrogen-bonding ability satisfied to stabilize it. Although glutamines can serve as hydrogen bond donors or acceptors, arginines can serve only as hydrogen bond donors. Therefore, the Q100R mutant now has two positively charged arginines at positions 100 and 97 in a hydrophobic area. This destabilizes the protein because both residues now need to form hydrogen bonds, but a hydrogen bond acceptor is not in proximity. The importance of the integrity of the Q100 and R97 residues is reflected by their absolute conservation in all Rpb6 and ω counterparts (Fig. 10C). Therefore, the Q100R mutation almost certainly changes the conformation of Rpb6 (possibly by changing the position of the surface-exposed loop next to positions 97 and 100 [viewed best at the top of panels A and B]). This putative conformational change may alter the activity of the enzyme and perturb the interaction of RNAP II with Rpb4 and Rpb7.

DISCUSSION

The function of the common subunits may change based on subunit context.

Since Rpb6 is assembled with all three RNAPs, its function was assumed to be identical. From a screen for random mutants that alter transcription, we identified a mutant form of the Rpb6 subunit assembled into RNAP I, II, and III that has differential effects on transcription. Other examples of common subunits with variable effects on transcription by RNAPs I, II, and III have been reported previously (44, 50). The Rpb6 Q100R mutation falls within a region corresponding to a very conserved hydrophobic area that forms a shallow groove predicted previously to form a surface for protein-protein interactions (12). We have shown that this is indeed the case, but the interaction partner was the Rpb4/Rpb7 subcomplex instead of the more obvious partner, Rpb1. Interestingly, two recent reports have revealed that subunits functionally related to the Rpb4/Rpb7 subunit pair exist in both RNAP I (A14 and A43) and RNAP III (C17 and C25) (18a, 41, 46). It is not yet known which subunit(s) these Rpb4/Rpb7 counterparts interact with in the context of their respective RNAPs.

Rpb4/Rpb7 interacts with RNAP II through Rpb6.

We have determined that Rpb6 serves as one point of contact for Rpb4/Rpb7 with the remainder of RNAP II. Although these substoichiometric subunits are absent from the highest-resolution crystal structures, previous work has predicted that the Rpb4 and Rpb7 subunits reside near the DNA binding cleft on the enzyme (1, 21). Their estimated position was recently refined with an 18-Å crystal structure (8). This study places the Rpb4/Rpb7 subunit pair in proximity to Rpb6 (the precise positions of individual subunits are not readily discernible at this level of resolution), consistent with the Rpb6-Rpb4/Rpb7 interaction that we have documented. Finally, using two-hybrid analysis, we have determined that Rpb4, and not Rpb7, is the likely point of contact between Rpb6 in RNAP II and the Rpb4/Rpb7 complex.

Connecting Rpb4/Rpb7 function to Rpb6.

Rpb4/Rpb7 is important for transcription initiation since in vitro transcription with nuclear extracts prepared from cells lacking the RPB4 gene showed marginal levels of basal transcription and greatly reduced levels of activated transcription (14). This effect was similar to our in vitro transcription results (Fig. 2B), suggesting that some of the effects described for our Rpb6 mutant may actually originate from the unstable Rpb4/Rpb7 association. When the RPB4 gene is deleted from living cells, RNAP II is rapidly inactivated at high temperatures and displays some transcriptional abnormalities at normal growth temperatures (30, 33).

Although the overall structures of the two enzymes are highly similar, RNAP II lacking Rpb4/Rpb7 is in a more open conformation, while crystals from the wild-type enzyme are in a closed conformation (1, 8, 21). The proximity of Rpb4/Rpb7 to the flexible clamp and its influence on clamp position in low-resolution structures suggests that this subunit pair may modulate the position of this flexible module (10). In the high-resolution RNAP II structure lacking Rpb4/Rpb7, Rpb6 is in proximity to the clamp in a location consistent with a regulatory role for Rpb6 in clamp movement. Rpb6 is connected to the base of the clamp through a set of five “switches” that serve as control panels for clamp movement (10). The newfound association of the Rpb4/Rpb7 pair with the Rpb6 subunit both (i) explains previous observations linking both of these subunits with modulation of clamp movement and (ii) suggests that Rpb4/Rpb7 may regulate the position of the clamp by signaling through Rpb6, possibly at the level of phosphorylation.

Rpb4 and Rpb7 have been hypothesized to play a role in modulation of RNAP II activity. Rpb4 and Rpb7 are present at substoichiometric levels, and the subunit pair has been reported to preferentially associate with RNAP II during stress and stationary phase (6). There are also conflicting reports in the literature about the localization of these subunits. In one study, a portion of S. pombe Rpb4 was reported to be cytoplasmic (23). In another study, on human subunits, Rpb4 was exclusively nuclear while Rpb7 localization varied. Human Rpb7 is mainly nuclear, but a portion of the subunit is also present in the cytoplasm (23). Rpb7 has also been the only RNAP II subunit repeatedly surfacing in two-hybrid interaction screens with mammalian transcription factors as bait (40, 57). Finally, previous studies on the recently identified mammalian counterpart of the RNAP III subunit C17 (related to Rpb4) called CGRP-RCP focused on its role in signal transduction (46).

A new function for Rpb6.

Both genetic and direct interactions between Rpb1 and Rpb6 have been documented previously (32, 39). In fact, Rpb6 and ω have been proposed to promote subunit assembly by stabilizing the largest RNAP subunit. In this scenario, Rpb6 and ω act by latching two conserved segments of the largest subunits to their C-terminal tails, resulting in less conformational entropy (32). We have demonstrated that Rpb6 has another distinct function involving an Rpb4/Rpb7 association. Examination of the atomic structure for RNAP II revealed that the Q100 region of Rpb6 does not contact Rpb1; the region of Rpb6 analogous to the region of ω that interacts with Rpb1 is on the side of Rpb6 opposite that of Q100. As with Rpb3 and its α subunit counterpart in bacteria, certain basic functions are preserved from bacteria to eukaryotes while new features facilitate enhanced regulatory complexity. While both bacterial and eukaryotic RNAP II have movable clamps involving Rpb1/β′, Rpb2/β, and Rpb6/ω (9, 10, 37, 53), ω is not known to be phosphorylated and there are no apparent functional counterparts to Rpb4 and Rpb7 in bacteria. Recent studies on S. pombe have revealed that the Rpb4 subunit interacts with the Rpb1 CTD phosphatase Fcp1 (24). Therefore, certain characteristics of the Rpb4/Rpb7 complex as well as CTD phosphorylation are linked to Rpb6 function. All of these proteins, Fcp1, Rpb4/Rpb7, and Rpb6, may contribute to clamp movement and/or cooperate in other RNAP II functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Ebright for numerous conversations and insights and for contributing panels A and B of Fig. 10; Michael Hampsey and Yuh-Hwa Wang for scientific discussions; and Bo-Shiun Chen for technical advice. We are grateful to Steve Hahn for kindly providing the Rpb9-TAP-tagged yeast strain. Gal4-VP16 was provided by the laboratory of Danny Reinberg. Finally, we thank Angela Then for sequencing the Rpb6 mutants and Keith McKune for technical assistance.

This work was funded by grant GM 55736 from the National Institutes of Health to N.A.W. M.H.P. was supported by a training grant, Virus-Host Interactions in Eukaryotic Cells from NIH-NIAID 2 T32 AI07403-10, awarded to Sidney Pestka.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asturias, F. J., G. D. Meredith, C. L. Poglitsch, and R. D. Kornberg. 1997. Two conformations of RNA polymerase II revealed by electron crystallography. J. Mol. Biol. 272:536-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awrey, D. E., R. G. Weilbaecher, S. A. Hemming, S. M. Orlicky, C. M. Kane, and A. M. Edwards. 1997. Transcription elongation through DNA arrest sites. A multistep process involving both RNA polymerase II subunit RPB9 and TFIIS J. Biol. Chem. 272:14747-14754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeke, J. D., J. Trueheart, G. Natsoulis, and G. R. Fink. 1987. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 154:164-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke, D., D. Dawson, and T. Stearns. 2000. Methods in yeast genetics. A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 5.Cho, E. J., M. S. Kobor, M. Kim, J. Greenblatt, and S. Buratowski. 2001. Opposing effects of Ctk1 kinase and Fcp1 phosphatase at Ser 2 of the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain. Genes Dev. 15:3319-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choder, M., and R. A. Young. 1993. A portion of RNA polymerase II molecules has a component essential for stress responses and stress survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6984-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack, B. P., and K. Struhl. 1992. The TATA-binding protein is required for transcription by all three nuclear RNA polymerases in yeast cells. Cell 69:685-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craighead, J., W. Chang, and F. Asturias. 2002. Structure of yeast RNA polymerase II in solution. Implications for enzyme regulation and interaction with promoter DNA. Structure 10:1117-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer, P., D. A. Bushnell, J. Fu, A. L. Gnatt, B. Maier-Davis, N. E. Thompson, R. R. Burgess, A. M. Edwards, P. R. David, and R. D. Kornberg. 2000. Architecture of RNA polymerase II and implications for the transcription mechanism. Science 288:640-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cramer, P., D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 2001. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science 292:1863-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darst, S. A. 2001. Bacterial RNA polymerase. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.del Rio-Portilla, F., A. Gaskell, D. Gilbert, J. A. Ladias, and G. Wagner. 1999. Solution structure of the hRPABC14.4 subunit of human RNA polymerases. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dezelee, S., F. Wyers, A. Sentenac, and P. Fromageot. 1976. Two forms of RNA polymerase B in yeast. Proteolytic conversion in vitro of enzyme BI into BII. Eur. J. Biochem. 65:543-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards, A. M., C. M. Kane, R. A. Young, and R. D. Kornberg. 1991. Two dissociable subunits of yeast RNA polymerase II stimulate the initiation of transcription at a promoter in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 266:71-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gnatt, A. L., P. Cramer, J. Fu, D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 2001. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 angstrom resolution. Science 292:1876-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha, I., S. Roberts, E. Maldonado, X. Sun, L. U. Kim, M. Green, and D. Reinberg. 1993. Multiple functional domains of human transcription factor IIB: distinct interactions with two general transcription factors and RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 7:1021-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hampsey, M. 1997. A review of phenotypes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13:1099-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Hu, P., S. Wu, Y. Sun, C. C. Yuan, R. Kobayashi, M. P. Myers, and N. Hernandez. 2002. Characterization of human RNA polymerase III identifies orthologues for Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase III subunits. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8044-8055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishiguro, A., Y. Nogi, K. Hisatake, M. Muramatsu, and A. Ishihama. 2000. The Rpb6 subunit of fission yeast RNA polymerase II is a contact target of the transcription elongation factor TFIIS. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1263-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James, P., J. Halladay, and E. A. Craig. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144:1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen, G. J., G. Meredith, D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 1998. Structure of wild-type yeast RNA polymerase II and location of Rpb4 and Rpb7. EMBO J. 17:2353-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayukawa, K., Y. Makino, S. Yogosawa, and T. Tamura. 1999. A serine residue in the N-terminal acidic region of rat RPB6, one of the common subunits of RNA polymerases, is exclusively phosphorylated by casein kinase II in vitro. Gene 234:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimura, M., H. Sakurai, and A. Ishihama. 2001. Intracellular contents and assembly states of all 12 subunits of the RNA polymerase II in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:612-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura, M., H. Suzuki, and A. Ishihama. 2002. Formation of a carboxy-terminal domain phosphatase (Fcp1)/TFIIF/RNA polymerase II (pol II) complex in Schizosaccharomyces pombe involves direct interaction between Fcp1 and the Rpb4 subunit of pol II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1577-1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolodziej, P. A., N. Woychik, S. M. Liao, and R. A. Young. 1990. RNA polymerase II subunit composition, stoichiometry, and phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:1915-1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, Y. C., S. Min, B. S. Gim, and Y. J. Kim. 1997. A transcriptional mediator protein that is required for activation of many RNA polymerase II promoters and is conserved from yeast to humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4622-4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leuther, K. K., D. A. Bushnell, and R. D. Kornberg. 1996. Two-dimensional crystallography of TFIIB- and IIE-RNA polymerase II complexes: implications for start site selection and initiation complex formation. Cell 85:773-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao, S. M., I. C. Taylor, R. E. Kingston, and R. A. Young. 1991. RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain contributes to the response to multiple acidic activators in vitro. Genes Dev. 5:2431-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magill, C. P., S. P. Jackson, and S. D. Bell. 2001. Identification of a conserved archaeal RNA polymerase subunit contacted by the basal transcription factor TFB. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46693-46696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maillet, I., J. M. Buhler, A. Sentenac, and J. Labarre. 1999. Rpb4p is necessary for RNA polymerase II activity at high temperature. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22586-22590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKune, K., and N. A. Woychik. 1994. Functional substitution of an essential yeast RNA polymerase subunit by a highly conserved mammalian counterpart. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4155-4159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minakhin, L., S. Bhagat, A. Brunning, E. A. Campbell, S. A. Darst, R. H. Ebright, and K. Severinov. 2001. Bacterial RNA polymerase subunit omega and eukaryotic RNA polymerase subunit RPB6 are sequence, structural, and functional homologs and promote RNA polymerase assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:892-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyao, T., J. D. Barnett, and N. A. Woychik. 2001. Deletion of the RNA polymerase subunit RPB4 acts as a global, not stress-specific, shut-off switch for RNA polymerase II transcription at high temperatures. J. Biol. Chem. 276:46408-46413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muhlrad, D., R. Hunter, and R. Parker. 1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast 8:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukherjee, K., and D. Chatterji. 1997. Studies on the omega subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase—its role in the recovery of denatured enzyme activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 247:884-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murakami, K. S., S. Masuda, and S. A. Darst. 2002. Structural basis of transcription initiation: RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 4 angstrom resolution. Science 296:1280-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers, L. C., and R. D. Kornberg. 2000. Mediator of transcriptional regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:729-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narlikar, G. J., H. Y. Fan, and R. E. Kingston. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nouraini, S., J. Archambault, and J. D. Friesen. 1996. Rpo26p, a subunit common to yeast RNA polymerases, is essential for the assembly of RNA polymerases I and II and for the stability of the largest subunits of these enzymes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:5985-5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perbal, B. 1999. Nuclear localisation of NOVH protein: a potential role for NOV in the regulation of gene expression. Mol. Pathol. 52:84-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peyroche, G., E. Levillain, M. Siaut, I. Callebaut, P. Schultz, A. Sentenac, M. Riva, and C. Carles. 2002. The A14-A43 heterodimer subunit in yeast RNA pol I and their relationship to Rpb4-Rpb7 pol II subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14670-14675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puig, O., F. Caspary, G. Rigaut, B. Rutz, E. Bouveret, E. Bragado-Nilsson, M. Wilm, and B. Seraphin. 2001. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods 24:218-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rigaut, G., A. Shevchenko, B. Rutz, M. Wilm, M. Mann, and B. Seraphin. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:1030-1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubbi, L., S. Labarre-Mariotte, S. Chedin, and P. Thuriaux. 1999. Functional characterization of ABC10α, an essential polypeptide shared by all three forms of eukaryotic DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 274:31485-31492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruet, A., A. Sentenac, P. Fromageot, B. Winsor, and F. Lacroute. 1980. A mutation of the B220 subunit gene affects the structural and functional properties of yeast RNA polymerase B in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 255:6450-6455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siaut, M., C. Zaros, E. Levivier, M. L. Ferri, M. Court, M. Werner, I. Callebaut, P. Thuriaux, A. Sentenac, and C. Conesa. 2003. An Rpb4/Rpb7-like complex in yeast RNA polymerase III contains the orthologue of mammalian CGRP-RCP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:195-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan, Q., K. L. Linask, R. H. Ebright, and N. A. Woychik. 2000. Activation mutants in yeast RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 provide evidence for a structurally conserved surface required for activation in eukaryotes and bacteria. Genes Dev. 14:339-348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson, N. E., D. B. Aronson, and R. R. Burgess. 1990. Purification of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II by immunoaffinity chromatography. Elution of active enzyme with protein stabilizing agents from a polyol-responsive monoclonal antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7069-7077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Treco, D. A., and V. Lundblad. 1993. Preparation of yeast media, p. 13.1.1-13.1.7. In K. Janssen (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 2. Greene Publishing Associates, Inc. and John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Voutsina, A., M. Riva, C. Carles, and D. Alexandraki. 1999. Sequence divergence of the RNA polymerase shared subunit ABC14.5 (Rpb8) selectively affects RNA polymerase III assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:1047-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warner, J. R., and C. Gorenstein. 1978. Yeast has a true stringent response. Nature 275:338-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wootner, M., P. A. Wade, J. Bonner, and J. A. Jaehning. 1991. Transcriptional activation in an improved whole-cell extract from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4555-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woychik, N. A. 1998. Fractions to functions: RNA polymerase II thirty years later. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woychik, N. A., and R. A. Young. 1989. RNA polymerase II subunit RPB4 is essential for high- and low-temperature yeast cell growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:2854-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang, G., E. A. Campbell, L. Minakhin, C. Richter, K. Severinov, and S. A. Darst. 1999. Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase at 3.3 angstrom resolution. Cell 98:811-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, Y., and D. Reinberg. 2001. Transcription regulation by histone methylation: interplay between different covalent modifications of the core histone tails. Genes Dev. 15:2343-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou, H., and K. A. Lee. 2001. An hsRPB4/7-dependent yeast assay for trans-activation by the EWS oncogene. Oncogene 20:1519-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]