Abstract

Studies of yeast have shown that the SIR2 gene family is involved in chromatin structure, transcriptional silencing, DNA repair, and control of cellular life span. Our functional studies of human SIRT2, a homolog of the product of the yeast SIR2 gene, indicate that it plays a role in mitosis. The SIRT2 protein is a NAD-dependent deacetylase (NDAC), the abundance of which increases dramatically during mitosis and is multiply phosphorylated at the G2/M transition of the cell cycle. Cells stably overexpressing the wild-type SIRT2 but not missense mutants lacking NDAC activity show a marked prolongation of the mitotic phase of the cell cycle. Overexpression of the protein phosphatase CDC14B, but not its close homolog CDC14A, results in dephosphorylation of SIRT2 with a subsequent decrease in the abundance of SIRT2 protein. A CDC14B mutant defective in catalyzing dephosphorylation fails to change the phosphorylation status or abundance of SIRT2 protein. Addition of 26S proteasome inhibitors to human cells increases the abundance of SIRT2 protein, indicating that SIRT2 is targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome. Our data suggest that human SIRT2 is part of a phosphorylation cascade in which SIRT2 is phosphorylated late in G2, during M, and into the period of cytokinesis. CDC14B may provoke exit from mitosis coincident with the loss of SIRT2 via ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome.

As the founding member of a vast gene family with members present in archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes, SIR2 was first described in the budding yeast as a gene mediating the transcriptional silencing of the silent mating type (MAT) loci HML and HMR (14, 19). Additional functions for SIR2 in budding have been described, including the silencing of subtelomeric genes (telomere position effect [TPE]) and the regulation of transcription and recombination in the multiple tandem copies of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (for a review, see reference 12). Guarente, Sinclair, and coworkers have shown that the SIR2 gene may suppress aging in budding yeast, through a mechanism involving the suppression of extrachromosomal rDNA circles (ERCs) derived from errant intralocus recombination and suggested that SIR2-related genes in other organisms may be involved in the aging process as well, even in multicellular eukaryotes (13). The mechanism by which SIRT (an acronym for SIR2 related) genes retard aging in metazoans may involve caloric restriction (CR) instead of the ERCs found in yeast (22). Support for this hypothesis has recently come from the key finding that providing the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans with two copies of one of its SIR2-related genes (the gene normally found on chromosome IV) can extend the worm's life span by ∼50% (36). This extension of life span function is seen only for one of the three SIR2-related genes, Sir-2.1, encoding a large nuclear protein orthologous to that coded for by the SIR2-related gene known as SIRT1 in humans and SIR2α in mice. Neither of the other two SIRT genes in the worm (orthologous to the human SIRT4 and -6 genes) can provide this extension of life span.

Multiple SIRT genes are not limited to metazoans. Indeed, the genome of the budding yeast also encodes four additional SIRT genes, first described as homologous to Sir2 (HST), known as HST1, HST2, HST3, and HST4 (5). Unlike Sir2p, which is chiefly nuclear in localization, the protein Hst2p is cytoplasmic, and shows very weak silencing function on subtelomeric genes (TPE), with no remarkable effect on rDNA (29). The fully sequenced Drosophila melanogaster genome harbors five SIR2-related genes, orthologous to human SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT6. Recently Rosenberg and Parkhurst showed that the fly SIRT1 ortholog affects segmentation and sex determination (30), whereas deletion of the mouse SIRT1 gene results in defective embryogenesis and gametogenesis (25). Mice and humans harbor seven SIRT genes, including a SIRT3 gene (located at 11p15 only 40.8 kb from the H19 gene in the imprinted Beckwith-Wiedemann interval) and a SIRT7 gene not found in flies or nematodes. The function of the SIRT1 gene in humans (and its mouse ortholog, SIR2α) surprisingly falls outside of the yeast SIR2 functions, which relate in some way to chromatin structure. The mouse and human SIRT1 gene products of 120 kDa are nuclear proteins that bind directly to the tumor suppressor p53 via its DNA-binding (DB) domain and its C terminus (23, 39). Instead of involvement in a function relating to chromatin structure or gene silencing, the first glimpse at a mammalian SIRT gene suggests a role for SIRT1 in the p53 pathway, including its well-known roles in the response to DNA damage and in apoptosis, a complex cellular response not found in the budding yeast.

SIRT family members can be recognized in BLAST searches due to the presence of a conserved core of ∼203 amino acid (aa) residues (2). The archaebacterial family members are not much larger than this core, ranging in size from 245 to 253 aa in length. The additional ∼45 aa in the archaebacterial SIRT proteins occur as N- and C-terminal extensions flanking the conserved core. The eubacterial members are more divergent in length, ranging in size from 208 residues (Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans) to 299 residues (Streptomyces), with more variation in the N- and C-terminal extensions. Mammalian SIRT2, the focus of this work, is a protein not much larger than the largest prokaryotic SIRT protein. It is, however, considerably smaller than the founding member, Sir2, which is 562 residues in length. SIRT2 in mice and humans can be synthesized in two different forms (352 and 381 residues) as the result of alternative splicing: these forms are similar in size to Hst2 from budding yeast (357 residues). Like Hst2, mammalian SIRT2 is a cytoplasmic protein (1, 29, 43). The conserved core of SIRT proteins (∼203 residues, approximately 24 kDa) folds into an NAD+-binding protein with intrinsic protein deacetylase activity capable of removing the acetyl moiety from the ɛ-amino group of lysine residues in protein substrates, including the N terminus of histone H4 and the C terminus of p53. This apparent deacetylase activity of SIRT proteins differs from the histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity of other mammalian and yeast HDACs in its insensitivity to trichostatin A (TSA), insensitivity to sodium butyrate, and strict requirement for NAD+ as a cofactor. The proposed product of the enzymatic activity of Sir2, O-acetyl ADP-ribose (OAAR), is formed when Sir2 removes an acetyl group from a protein target and transfers the moiety to NAD. This final product as well as ADP-ribose, when injected into starfish oocytes or blastomeres, resulted in the delay or complete blockage of the cell cycle during development (4). Production of OAAR by SIRT proteins is coupled closely to NAD-dependent deacetylase (NDAC) activity, which raises the possibility that OAAR may act as a second messenger, the de novo generation by SIRT proteins of which is focal in the cell at the site where SIRT proteins interact with their acetylated substrates (6).

The protein deacetylase function presumed to be intrinsic to all SIRT proteins may be their only functional commonality. Thus, the chromatin remodeling properties of Sir2 in the budding yeast may be atypical of SIRT proteins, as might be expected from the fact that SIRT genes exist in prokaryotes that are devoid of histones. Presumably, eukaryotic SIRT proteins all share the NDAC activity, but differ in their cellular function due to general subcellular distribution and specific protein-protein interactions with their acetylated protein substrates, properties that would be unique to each SIRT ortholog and presumably determined by the folding of the N-and C-terminal extensions as Avalos et al. (2) have recently suggested. It would not be surprising to find functions for mammalian SIRT proteins that supercede chromatin remodeling, and indeed, we find this to be the case for SIRT2.

We find that human SIRT2 is a cytoplasmic protein that increases in abundance during mitosis (M phase). Using a highly specific rabbit antibody raised to the C terminus of human SIRT2, we have been able to resolve SIRT2 proteins into a family of isoforms that, according to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), differ in their extent of phosphorylation. Using cell synchronization techniques, we show that the hyperphosphorylated forms of SIRT2 are confined to the M phase of the cell cycle, coincident with the G2/M transition, and maintained throughout the M phase. We have derived cell lines expressing wild-type and NDAC-defective SIRT2 and found that the presence of excess SIRT2 NDAC activity severely delays cell cycle progression through mitosis. Because in budding yeast the CDC14 dual-specificity phosphatase (DSP) lies at the head of a signaling cascade regulating mitotic exit, we tested the ability of the two mammalian CDC14-related DSPs to regulate SIRT2 phosphorylation and/or abundance. We found that overexpression of CDC14B, but not CDC14A, leads to the loss of hyperphosphorylated SIRT2, and this effect is abolished by site-specific mutation of CDC14B that eliminates its phosphatase activity. Finally, we found that like other mitotic regulators such as the B-type cyclins, the human SIRT2 protein becomes ubiquitinylated and turns over via the 26S proteasome in a pathway downstream from CDC14B. These findings suggest a novel role for a SIRT protein: namely as a regulator of mitotic progression, presumably acting downstream from CDC14B in a pathway regulating mitotic exit or subsequent cytokinesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfections.

Saos2 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Invitrogen). For both transient and stable transfections, cells were seeded 24 h prior to transfection at 2.2 × 106 cells per 100-mm-diameter plate. Lipofectamine and Plus reagent (Invitrogen) were used for transfections according to the manufacturer's instructions. Unless otherwise indicated, 12 μg of DNA (purified with a Qiagen Maxiprep kit) was transfected per 100-mm-diameter culture dish. Transient transfections were harvested after 48 h. Epoxomicin (Biomol) treatments were initiated 3 h after transfection. For experiments involving epoxomicin, the transfection complexes were removed, and medium containing the inhibitors was added to the cells. Cultures were incubated for 20 h and then harvested. Transfected cells were very sensitive to the proteasome inhibitors. Lactacystin and clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (Sigma) caused extensive cell death and could not be used in transfected cells. For untransfected cells, lactacystin, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, and epoxomicin (each dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) were added to cell cultures at the concentrations indicated. After 8 h, fresh medium containing proteasome inhibitors was added, and cells were incubated for an additional 12 h prior to harvesting for Western blots.

Plasmid constructs and generation of stable clones.

The pEGFP-hCdc14A and pEGFP-hCdc14B plasmids were kindly provided by M. Ljungman (University of Michigan at Ann Arbor) and were used in transient transfections. The ubiquitin expression plasmid, pMT123, was provided by Y. Haupt (Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel). A cDNA containing the entire SIRT2 coding region (Research Genetics, clone T66100) was inserted into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1/HisC (Invitrogen). The resultant plasmid, pcDNA3.1-SIRT2, was sequenced to confirm that the SIRT2 open reading frame (ORF) was in-frame to allow expression of a His-tagged SIRT2 protein from the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter encoded on the vector. The resulting plasmid ORF predicted a 434-residue polypeptide with a calculated molecular mass of 48 kDa, tagged with six His residues. Stable transfectants were generated from Saos2 cells by selection in 100 μg of G418/Geneticin per ml (Invitrogen), initiated 72 h posttransfection. Cells were transfected with either pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 or the empty vector as a control. Individual clones were isolated with cloning cylinders approximately 3 to 4 weeks after selection was initiated and then expanded individually. Potential stable transfectants were analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) to confirm the presence of pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 or the empty vector. The primers used for RT-PCR were T7 (on the vector) and a primer internal to the SIRT2 gene (primer d2r-CTATGTTCTGCGTGTAGCAGCG) or T7 and the BGH reverse primer (Invitrogen) for the vector controls. When stable transfectants were analyzed for the presence of SIRT2 transcripts, four of eight transfectants showed increased RNA expression of the SIRT2 gene as determined by quantitative RT-PCRs (data not shown). Although these four clones showed elevated SIRT2 mRNA levels, Western blot analysis of the clones showed various levels of the different isoforms of SIRT2 protein (see Fig. 3).

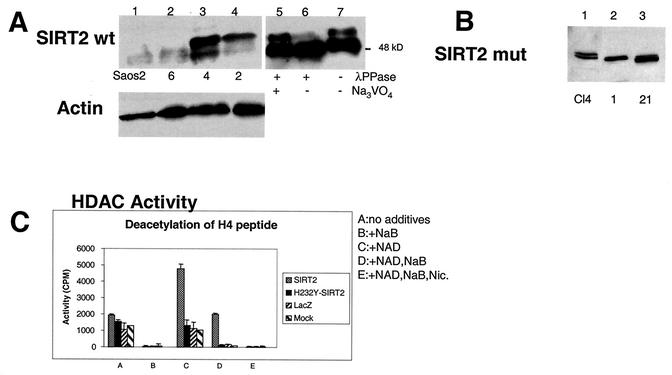

FIG. 3.

SIRT2 expression in stable transfectants of Saos2 cells. Saos2 cells stably transfected with pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 or pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 H232Y express various levels of the phosphorylated form of SIRT2. Crude lysates from individual clones were subjected to immunoblotting with the SIRT2 peptide antibody. (A) Stable transfectants expressing wild-type (wt) SIRT2. Cells ± λPPase and Na3VO4 were used as markers for phosphorylation status. Lanes: 1, untransfected Saos2 cells; 2, clone 6; 3, clone 4; 4, clone 2. Lanes 5 to 7 contained nocodazole-treated cells ± λPPase and Na3VO4. To control for protein loading, blots were also probed with actin (lower panel). (B) Stable transfectants expressing mutant SIRT2, in which histidine 232 was mutated to tyrosine. Lane 1 contained clone 4. Clones 1 and 21 (lanes 2 and 3, respectively) were used in subsequent experiments. (C) SIRT2 NDAC activity in various transfected Saos2 cell lines. Activity was assayed by monitoring the release of 3H-acetyl groups from an H4 peptide (counts per minute) under the conditions indicated. (D) The amino- and carboxy-terminal domains of the H232Y clones are intact. Nickel magnetic agarose beads were used to purify SIRT2. Crude cell lysates prior to pulldown assays are shown in lanes 1 and 2. Lysates and pulldown assays were subjected to immunoblotting with the SIRT2 peptide antibody. (E) Time course of λPPase digestion of SIRT2 stable transfectants. The hyperphosphorylated isoform appears to be the most labile, collapsing sequentially to the final hypophosphorylated SIRT2 isoform.

Site-directed mutagenesis of hCDC14B and SIRT2.

The forward primer GCCATTGCAGTACATTCCAAAGCTGGCCTTGGTCGC and a plasmid-encoded reverse primer, TGATCAGTTATCTAGATCCGGTGGA, were used in a PCR with pEGFP-hCdc14B to generate a 0.5-kb product. The forward primer had a single base change from the wild-type CDC14B sequence (underlined above); this changed the active-site cysteine (TGC) to serine (TCC). The 0.5-kb PCR product was gel purified (Qiagen gel purification kit). A second PCR was performed with the 0.5-kb fragment used as a reverse primer and an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) forward primer, GATCACATGGTCCTGCTGGAGTTC—again with pEGFP-hCdc14B as the template. The final 1.6-kb PCR product was digested with BamHI and KpnI and gel purified. The pEGFP-hCdc14B plasmid was also digested with BamHI and KpnI; this removed the wild-type CDC14B insert from the vector. Finally, the digested 1.6-kb PCR fragment was ligated into the BamHI-KpnI-linearized pEGFP vector and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10F′ cells (Invitrogen). The resulting Cdc14B C314S mutant was sequenced to confirm that the mutation in the Cdc14B ORF was as intended (codon 314) and no other inadvertant mutations were introduced.

Mutagenesis of SIRT2 was performed in two sequential steps. Two primer pairs (H232Y forward, GGAGGCGTACGGCACCTTCTACACATCACAC; pcDNA3.1 reverse, GCAAACAACAGATGGCTGGCAAC; and pcDNA3.1 forward, GAACCCACTGCTTACTGGCTTATC; H232Y reverse, GTGTAGAAGGTGCCGTACGCCTCCTCC) were used in PCRs to produce 1.3- and 0.7-kb fragments, respectively. The H232Y forward and reverse primers have a single base change from the wild-type SIRT2 sequence (underlined above); this changed the conserved histidine (CAC) to tyrosine (TAC). The PCR products were gel purified and then reamplified with the pcDNA3.1 forward and reverse primers (shown above) to produce a final 2.0-kb PCR product. This was digested with Bst98I and NotI, ligated into Bst98I-NotI-linearized pcDNA3.1/HisC vector, and transformed into E. coli TOP10F′ cells. The resulting SIRT2 H232Y mutant was confirmed by sequencing. SIRT2 H232Y stable transfectants were generated as described above. Clones for further analysis were identified by Western blotting and RT-PCR.

Cell synchronization.

In initial experiments, cells were synchronized by double-thymidine block and then treated with nocodazole or Colcemid. Cells at ∼60% confluency were treated with 2 mM thymidine in complete medium without antibiotics for 17 h and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in fresh drug-free medium for 9 h. The cells were then retreated with 2 mM thymidine for 16 h and again allowed to recover for 9 h in fresh medium. Such treatment resulted in cells primarily (>90%) in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. The cells were then incubated in medium containing either 0.4 μg of nocodazole per ml (arrest at the G2/M boundary) or 17 ng of Colcemid per ml (arrest in mid-M phase) for 16 h. The cells were prepared in duplicate for analysis by both flow cytometry and immunoblotting. For analysis of cell recovery from a nocodazole block, 2.2 × 106 cells seeded in 100-mm-diameter dishes 24 h prior to nocodazole addition were grown in complete medium and synchronized by the addition of 0.4 μg of nocodazole per ml for 20 h. Nocodazole-containing medium was then removed, and the cells were incubated in fresh normal medium at 37°C for 5 min. The medium was removed, and cells were gently washed twice with PBS. Fresh drug-free medium was then added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C. The cells were harvested at the times indicated and analyzed by flow cytometry or Western blot.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were washed with PBS, treated with trypsin-EDTA, washed off the dish with normal medium, and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min. The cells were washed with 5 ml of PBS, centrifuged, and resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS. For fixation, the resuspended cells were added to 4.5 ml of ice-cold 70% ethanol and incubated for at least 2 h at −20°C. Fixed cells were then pelleted and stained with propidium iodide (Molecular Probes) as described previously (7). Flow cytometry was performed by the Wayne State University Flow Cytometry Core Facility by using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and ModFit LT v. 2.0 software. Each profile was compiled from at least 10,000 gated events.

Antibodies.

Antibody to SIRT2 was raised in rabbits by Zymed Laboratories with a synthetic peptide antigen corresponding to the carboxy-terminal 12 aa residues of the human SIRT2 protein (DEARTTEREKPQ). The rabbit antiserum was used at the indicated dilutions for all experiments. Actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz. The Ha-11 antibody, specific for the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope, was purchased from Covance. The secondary antibodies used were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or sheep anti-mouse (Pierce) immunoglobulin G (IgG) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Confocal microscopy.

Saos2 cells were grown on glass coverslips in 24-well tissue culture clusters (4 × 104 cells per well). After 24 h, the cells were washed eight times with Dulbecco's PBS (Invitrogen) and then washed for 10 min in PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde (in PBS) for 10 min, and then washed three times with PBS at room temperature. The fixed cells were incubated for 45 min in PBS with 0.2% bovine serum albumin and then washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% saponin. SIRT2 antibody (1:400 dilution in PBS-0.1% saponin) was added to the coverslips for 3 h at room temperature, and then the coverslips were washed six times with PBS-0.1% saponin. The secondary antibody (FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit) diluted 1:1,000, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes) diluted 1:1,000, and 5% normal donkey serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS-0.1% saponin were added to the coverslips, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h. The coverslips were again washed six times with PBS-0.1% saponin, refixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, washed with water, and mounted with Slow Fade (Molecular Probes) onto slides. As a control, fixed cells were also incubated in SIRT antibody that had been preincubated with the synthetic peptide antigen. No fluorescence was detected when such slides were imaged (data not shown). The slides were imaged at the Wayne State University Microscopy and Imaging Resources Laboratory with a Zeiss LSM-310 confocal microscope.

Western blot analysis.

Cells grown on 100-mm-diameter culture dishes were washed with PBS and then lysed directly on plates with RIPA buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS in PBS, supplemented with 1 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF] per ml, 10 μl of Sigma Protease inhibitor cocktail per ml, 0.1 M Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM NaPPO4). For lysates to be assayed with lambda protein phosphatase (λPPase), the phosphatase inhibitors were omitted. After shearing of genomic DNA through a 21-gauge syringe needle, lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min to 1 h. Debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 20 min in a microcentrifuge. The crude cell lysate was then concentrated with a 50-min spin at 6,300 rpm (Sorvall SS34 rotor) in a Centricon 30 filter unit (Millipore). For Western analysis, crude protein lysates in Laemmli sample buffer were heated to 95°C for 5 min and then separated on 18- by 16-cm SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) gels with an acrylamide/bisacrylamide mass ratio of 150:1. Gels were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST; 10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20)-0.5% powdered milk. SIRT2 antibody (1:1,000 dilution) in TBST-0.5% powdered milk was added for 1 h. Membranes to be probed with actin antibody (1:500 dilution) were incubated with the antibody overnight. The blots were washed twice for 15 min in TBST-0.05% milk, and then goat anti-rabbit or sheep anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody was added for 1 h (1:10,000 dilution). Blots were again washed twice for 15 min each in TBST-0.05% milk and then visualized with the Pierce Super Signal Pico West detection reagents per the manufacturer's instructions. The BenchMark prestained protein ladder (Invitrogen) was run on every gel; the fastest-migrating bands reactive with SIRT2 antibody migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 48 kDa.

λPPase treatments.

λPPase was purchased from New England Biolabs, and assays were performed as suggested by the manufacturer. Briefly, 10 μg of crude protein extract was incubated with 1× reaction buffer, 1× MnCl2, and with or without λPPase, as indicated (20-μl reaction volumes), for 30 min at 30°C. Where indicated, 0.1 mM Na3VO4 was added to inhibit the λPPase. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 2 μl of 250 mM EDTA. Laemmli sample buffer, containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol, was added, and samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min prior to loading on SDS-PAGE gels.

Nickel bead purification of SIRT2 and immunoprecipitations.

Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) magnetic agarose beads (Qiagen) were used to isolate the His-tagged SIRT2 protein according to the manufacturer's directions. Protein was purified under native conditions with 0.5 mg of crude lysate used for each isolation. The protein was eluted from the magnetic beads with 250 mM imidazole. Immunoprecipitations were performed with Ezview red protein A affinity gel (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions with the following changes. The crude lysates were precleared with 20 μl of the affinity gel for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube, 7 μl of SIRT2 antibody was added, and this mixture was then incubated for 2 h at 4 C with gentle, but thorough mixing. Incubation with affinity beads (20 μl) was performed overnight instead of for 1 h.

Peptide labeling and HDAC assay.

NDAC activity was measured with an HDAC kit (Upstate Biotechnology) by using 3H-labeled histone H4 peptide (supplied in the kit) per the manufacturer's instructions. Protein lysates from transient transfections of SIRT2 clones were assayed by incubating them in the presence of 100,000 cpm of 3H-labeled peptide according to the manufacturer's directions. Each deacetylase reaction mixture contained 100 μg of crude protein lysate in 200 μl of HDAC assay buffer. Where indicated, 250 mM sodium butyrate, 5 mM nicotinamide, and/or 0.5 mM NAD was added to a reaction mixture. All reactions were performed in duplicate, and the background for each experiment was determined with a reaction mixture that contained no protein.

RESULTS

PSORT predictions suggest that SIRT2 is a cytoplasmic protein.

Frye (10) performed a phylogenetic analysis of predicted proteins related to yeast SIR2 and defined seven classes, including what he referred to as class I, further subdivided into class Ia and class Ib. According to this classification, the human SIRT2 protein falls into class Ib, along with the closely related SIRT3 protein. The other human SIRT proteins (i.e., SIRT1, -4, -5, -6, and -7) are structurally distinct from SIRT2 and SIRT3 (Table 1). An analysis of amino acid motifs for protein sorting and trafficking by using the P-SORT-II algorithms based on the k-nearest neighbors classifier (28) predicts that SIRT2 would be cytoplasmic in localization (Table 1), consistent with experimental data (Fig. 1) (1, 43). Based on these predictions, SIRT1, -6, and -7 should be nuclear, as has been demonstrated for SIRT1 (23, 39). SIRT3 and SIRT4 are predicted to be located in the endoplasmic reticulum. Recent data, however, indicate that SIRT3 is synthesized as an enzymatically inactive precursor that is processed upon entry into the mitochondria. The mature, processed form of SIRT3 then becomes located in the mitochondrial matrix, where it is enzymatically active (31).

TABLE 1.

Classification of SIR2-related genes

| Gene name | NCBI LocusLink IDa | Human chromosomal location | Protein product(s), conceptual translation | PSORT protein predictions (results of the k-NN prediction)b | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | 23411 | 10q21.3 | Isoform 1 (747 aa), isoform 2 (555 aa) | SIRT1 (747 aa): 69.9% nuclear, 13.0% mitochondrial, 8.7% plasma membrane, 4.3% vesicles of secretory system, 4.3% cytoplasmic | Known as Sir1α in mice; ortholog of the Drosophila SIRT gene located at 34A7-8; ortholog of the C. elegans SIRT gene found on chromosome IV; probable ortholog identified in zebrafish as ESTc |

| SIRT2 | 22933 | 19q13.1 | Isoform 1 (389 aa), isoform 2 (352 aa) | SIRT2 (352 aa): 30.4% cytoplasmic, 21.7% mitochondrial, 17.4% extracellular (including cell wall), 17.4% nuclear, 4.3% cytoskeletal, 4.3% vacuolar, 4.3% endoplasmic reticulum | Known as SIR2L2 in mice ortholog of the Drosophila SIRT gene found on 3R92E; no apparent ortholog in C. elegans |

| SIRT3 | 23410 | 11p15.5 | Isoform A, (257 aa), isoform B (346 aa) | SIRT3 (399 aa): 44.4% endoplasmic reticulum, 22.2% Golgi, 11.1% mitochondrial, 11.1% nuclear, 11.1% cytoplasmic | Known as SIR2L3 in mice; no apparent ortholog in Drosophila or C. elegans |

| SIRT4 | 23409 | 12q | 314 aa | SIRT4 (314 aa): 33.3% endoplasmic reticulum, 22.2% vacuolar, 22.2% plasma membrane, 11.1% Golgi, 11.1% mitochondrial | Drosophila ortholog found at 65E5-6 on chromosome 3; in C. elegans there are 2 closely linked apparent orthologs on chromosome |

| SIRT5 | 23408 | 6pter-p25.1 | Isoform 1 (310 aa), isoform 2 (299 aa) | SIRT5 (310 aa): 65.2% mitochondrial, 8.7% cytoplasmic, 8.7% nuclear, 4.3% vacuolar, 4.3% extracellular (including cell wall) 4.3% plasma membrane, 4.3% peroxisomal | No apparent orthologs in either Drosophila or C. elegans |

| SIRT6 | 51548 | 19p13.3 | Isoform 1 (355 aa), isoform 2 (237 aa) | SIRT6 (355 aa): 78.3% nuclear, 13.0% cytoskeletal, 4.3% Golgi, 4.3% mitochondrial | Drosophila ortholog found at 3R 85F-86A; apparent C. elegans ortholog found on chromosome I |

| SIRT7 | 51547 | 17q25 | 400 aa | SIRT7 (400 aa): 56.5% nuclear, 26.1% cytoplasmic, 13.0% mitochondrial, 4.3% cytoskeletal | No apparent orthologs in either Drosophila or C. elegans |

LocusLink ID is available from the electronic repository at the National Center for Biolotechnology Information (NCBI), available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/LocusLink.

PSORT prediction is a summation of results of the k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) prediction according to the predictive software accessible at http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/form2.html.

EST, expressed sequence tag.

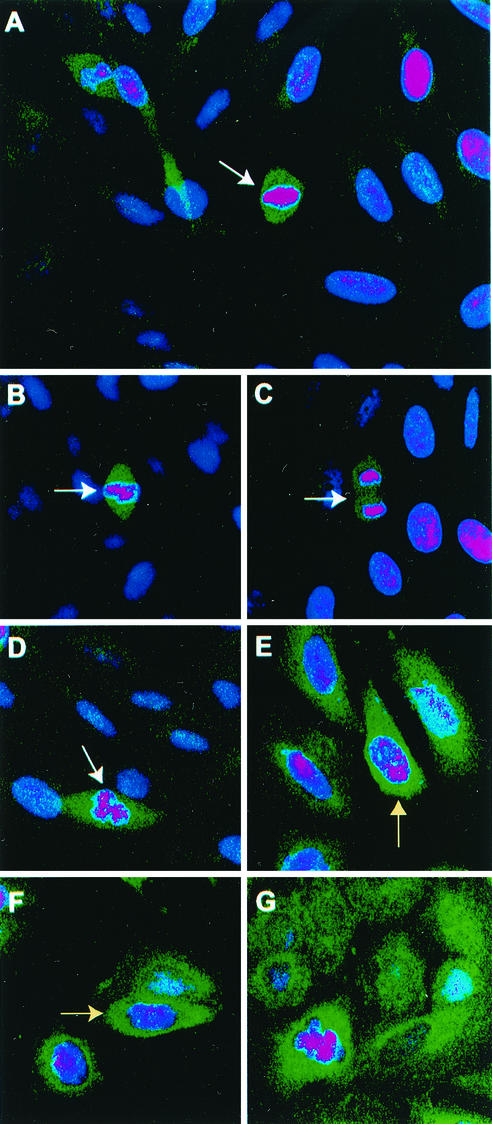

FIG. 1.

Staining of cells with SIRT2 antibody is tightly confined to cells in late G2 or M phase. Confocal microscopy was performed on Saos2 cells grown on coverslips as described in Materials and Methods. DAPI (dihydrochloride)-stained nuclei appear pink. DAPI stain is blue, but in the interests of contrast, the color was enhanced. A green fluorescent FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used to localize the rabbit SIRT2 peptide primary antibody. White arrows point to mitotic cells. (A) Full-field view of unsynchronized Saos2 cells. Only mitotic cells exhibit intense SIRT2 staining. (B to D) Close-up views of individual Saos2 mitotic cells. (E and F) Saos2 cells blocked at G2/M with nocodazole. The intense SIRT2 staining tightly surrounds the condensing chromatin (indicated by yellow arrows). (G) Saos2 cells blocked in metaphase with Colcemid. Again, SIRT2 is intensified around the chromatin.

SIRT2 increases in abundance during mitosis and becomes phosphorylated.

In yeast, SIR proteins are involved in gene silencing and DNA repair and are accordingly localized to the nucleus. However, Hst2, the yeast Sir2-related protein, is strictly cytoplasmic and most closely related to the human SIRT2 protein (29). To define localization of the SIRT2 gene product within mammalian cells, we analyzed Saos2 osteosarcoma cells by immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. Very little SIRT2 protein could be visualized in the majority of cells, but that which could be detected appeared to be cytoplasmic. Previous studies of mouse and human SIRT2 proteins have revealed a similar localization (1, 29, 43). However, we found that in these unsynchronized cell populations, within those cells undergoing mitosis, the SIRT2 protein was far more abundant (Fig. 1A to D). We also performed Western blot analysis and found there was also substantially more SIRT2 protein expression in mitotic cells (described below). These results suggested that SIRT2 protein is regulated during the cell cycle, increasing in abundance specifically during mitosis.

In order to confirm the cell cycle regulation of SIRT2, we analyzed Saos2 cells that had been arrested at various phases of the cell cycle; in G1 by double-thymidine block (37) or in G2/M with nocodazole or Colcemid. SIRT2 was substantially more abundant in both nocodazole (Fig. 1E and F)- and Colcemid (Fig. 1G)-treated cells compared to control untreated cells (Fig. 1A to D). In the nocodazole-treated cells, SIRT2 immunoreactivity appeared to remain cytoplasmic but tightly surrounds the condensing chromatin (Fig. 1E and F, yellow arrows). In the Colcemid-treated cells, the DAPI-stained chromatin was quite distinct, and SIRT2 immunoreactivity was intense throughout the cell (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that there is a marked increase in SIRT2 protein abundance at the G2/M transition. It should also be noted that SIRT2 immunoreactivity is intense in a pair of daughter cells (Fig. 1A) that have reformed their nuclear envelopes and thus have completed telophase and are in the process of cytokinesis.

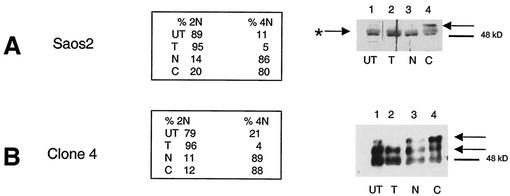

We next analyzed SIRT2 protein phosphorylation in Saos2 cells that had been released from G1 arrest and subsequently blocked at G2/M with nocodazole or M phase with Colcemid. At each arrest, cells were harvested in parallel for DNA content analysis by flow cytometry and for SIRT2 protein content by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). Untreated cells or cells blocked with thymidine contained a predominant 48-kDa SIRT2 band (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). This protein species appeared to be a doublet, which may be due to posttranslational modification or detection of both isoforms of SIRT2. This doublet is present in samples that have been treated with λPPase, which strongly suggests that these two species do not differ by phosphorylation status (described below). Saos2 cells arrested with Colcemid displayed an ∼50-kDa phosphorylated form of SIRT2 (Fig. 2A, lane 4). When untreated Saos2 cells or double-thymidine-block-arrested Saos2 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, we found that the cells were predominantly in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (>89%) and contained little of this phospho-SIRT2. Greater than 80% of cells treated with nocodazole or Colcemid contained a 4N DNA content (Fig. 2A) and increased amounts of phospho-SIRT2 (Fig. 2A, lane 4). These results indicated that there might be a correlation between the SIRT2 phosphorylation status and cell cycle progression through mitosis.

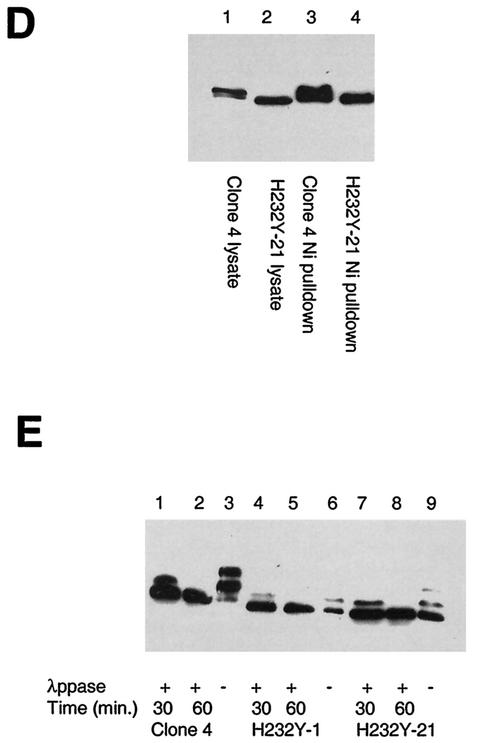

FIG. 2.

There is increased phosphorylation of SIRT2 protein at G2 and in M phase. SIRT2-overexpressing cells are hyperphosphorylated. Saos2 cells (A) and a stable transfectant overexpressing SIRT2 (clone 4 in panel B) were synchronized by double-thymidine block and subsequently treated with nocodazole or Colcemid. The DNA content of synchronized cells was assayed by flow cytometry to confirm the effectiveness of cell cycle blocks. The percentage of cells with a 2N (G1 and S phase) or 4N (G2 and M phase) DNA content is shown. Cell lysates were harvested at each step during synchronization and immunoblotted with SIRT2 peptide antibody. Arrows point to the phosphorylated isoforms. The arrow with an asterisk indicates λPPase-insensitive isoforms of SIRT2. UT, untreated, unsynchronized cells; T, cells harvested after the double-thymidine block; N, cells subsequently treated with nocodazole; C, cells treated with Colcemid after thymidine treatment. Blockade in M phase (Colcemid) results in a more pronounced shift of SIRT2 to the phosphorylated isoform in Saos2 cells.

Because the endogenous level of SIRT2 protein is very low, stable SIRT2 transfectants were generated in Saos2 cells and characterized for their level of SIRT2 protein abundance. One of the transfectants, clone 4, overexpressed all forms of SIRT2 and revealed a new, more highly phosphorylated form of SIRT2 (with an apparent molecular mass of 51 kDa). The phosphorylation status of SIRT2 was analyzed by Western blot analysis of clone 4 cells by arresting these cells in G1 with a double-thymidine block, releasing them and then subsequently adding nocodazole or Colcemid. The second phosphorylated species (51 kDa) increased in abundance when cells were blocked in G2/M or at M (Fig. 2B). The 51-kDa SIRT2 isoform was not present in G1-arrested clone 4 cells. Note that the 4N (G2/M) content of thymidine-arrested cells was only 4%. The untreated clone 4 cells also contained the 51-kDa form, perhaps because 21% of the unsynchronized cells were in G2/M (Fig. 2B). The hyperphosphorylation observed here parallels the phosphorylation observed with the endogenous SIRT2 protein in the parental Saos2 cell line. To demonstrate that the forms of SIRT2 observed in G2/M cells differed from the SIRT2 protein in G1 cells by a phosphorylation event, a cell lysate from clone 4 cells was incubated with λPPase (44). This enzyme catalyzes release of phosphate from phosphoserine, phosphothreonine, and phosphotyrosine residues. λPPase dephosphorylated SIRT2 and reduced the protein to a single band (Fig. 3A, lane 7). This change was inhibited by Na3VO4, a phosphatase inhibitor (Fig. 3A, lane 5).

Analysis of wild-type and NDAC-defective SIRT2 stable transfectants.

Western blot analysis of four wild-type SIRT2 stable transfectants (clones 2, 4, and 6) revealed various levels of the different isoforms of SIRT2 protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 2-4). As expected, a clone stably transfected with the empty pcDNA3.1 vector (data not shown) and untransfected cells showed no increase in SIRT2 protein or its phosphorylated forms (Fig. 3A, lane 1). Note that the unphosphorylated forms of SIRT2 are visible as a tight doublet of 48 kDa and a doublet of approximately 48.5 kDa when the phosphorylated form is not highly prominent. (Overexpression of the phosphorylated SIRT2 often masks this tight doublet, but it is clearly visible in Fig. 2A and is indicated by the arrow with an asterisk.) Treatment with λPPase does not affect these two endogenous SIRT2 isoforms. The same two λPPase-insensitive isoforms are also present in clone 4 (which can be seen below in Fig. 5D, lane 1). Therefore, SIRT2 protein appears to be modified by an additional posttranslational mechanism other than phosphorylation. The nature of these modifications of SIRT2 is under investigation.

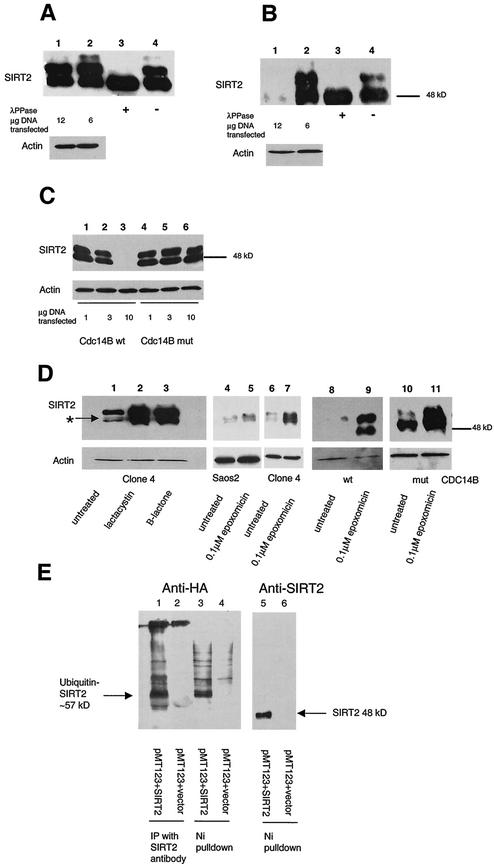

FIG.5.

Transfection of functional Cdc14B into clone 4 causes SIRT2 protein levels to decrease and targets SIRT2 for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome. Clone 4 cells were transiently transfected with CDC14A, CDC14B, or the CDC14B C314S mutant at the indicated DNA concentrations. As a control, a lysate from untransfected clone 4 cells was treated with or without λPPase (lanes 3 and 4, respectively, in panels A and B). Ten micrograms of crude protein lysate was loaded in each lane and subjected to immunoblotting with the SIRT2 peptide antibody. (A) Clone 4 transfected with CDC14A. There was very little change in SIRT2 when either 6 or 12 μg of CDC14A DNA was transfected into cells (lanes 1 and 2). The arrow marked with an asterisk indicates the unphosphorylated SIRT2 isoforms. (B) Clone 4 transfected with CDC14B. When 12 μg of CDC14B was transfected into cells, there was a dramatic decrease in protein and loss of the phosphorylated SIRT2 (lane 1). (C) Clone 4 transfected with the either CDC14B wild type (wt) or a Cdc14B C314S mutant (mut) that has no phosphatase activity. With increasing amounts of CDC14B, there was a corresponding decrease in SIRT2 (lanes 1 to 3). There was no change in SIRT2 with increasing concentrations of the CDC14B C314S mutant plasmid (lanes 4 to 6). (D) The 26S proteasome inhibitors lactacystin, clasto-lactacystin β-lactone, and epoxomicin stabilize SIRT2 isoforms and prevent ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Following a 20-h incubation with the indicated inhibitors, cells were harvested and processed for Western blot analysis. Lanes: 1 and 6, untreated clone 4 lysates; 2, clone 4 treated with 10 μM lactacystin; 3, clone 4 treated with 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone; 4, untreated Saos2 lysate; 5, Saos2 treated with 0.1 μM epoxomicin; 7, clone 4 treated with 0.1 μM epoxomicin; 8 and 9, clone 4 transfected with CDC14B (wt) minus or plus 0.1 μM epoxomicin, respectively; 10 and 11, clone 4 transfected with CDC14B C314S (mut) minus or plus 0.1 μM epoxomicin, respectively. To control for protein loading, all blots were probed with actin as well. (E) SIRT2 and ubiquitin coprecipitate in both nickel magnetic agarose bead pulldown assays and protein A SIRT2 immunoprecipitations. Saos2 cells were transiently cotransfected with the HA-tagged, ubiquitin-expressing plasmid pMT123 and either pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 or the empty vector pcDNA3.1/HisC. Lysates from the transfected cells were incubated with Ni-NTA magnetic agarose beads or SIRT2 antibody bound to protein A affinity gel. Samples were processed as described above and immunoblotted with HA-ll antibody (lanes 1 to 4) or SIRT2 peptide antibody (lanes 5 and 6).

In addition, stable Saos2 cell lines were generated by using a mutated SIRT2 in which a highly conserved histidine 232 necessary for protein deacetylase activity was changed to tyrosine (9). Representative stable clones are shown in Fig. 3B. As with the wild-type SIRT2 clones, various levels of expression were seen. Two clones (H232Y-1 and H232Y-21 in Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3, respectively) were chosen for further study because they expressed the mutant SIRT2 to about the same level as wild-type SIRT2 clone 4.

When cell lysates were examined for NDAC activity, the cells overexpressing wild-type SIRT2 protein contained NDAC activity, whereas those expressing the H232Y SIRT2 mutant protein were devoid of SIRT2 NDAC activity (Fig. 3C). These assays were performed with an acetylated histone peptide as a substrate (16). The NDAC levels in H232Y-1 and H232Y-21 were similar to the activity of control Saos2 or LacZ-transfected cells (Fig. 3C). Note that NDAC activity of SIRT2 is specifically dependent on NAD, resistant to sodium butyrate, and sensitive to nicotinimide (Fig. 3C).

The H232Y SIRT2 protein is phosphorylated in a similar fashion to the wild-type SIRT2 in clone 4. The SIRT2 protein in the H232Y stable transfectants appeared to be phosphorylated following treatment with nocodazole, although to a lesser extent than the SIRT2 protein in clone 4 cells (Fig. 3E). In order to analyze this phosphorylation, lysates were isolated from clone 4, H232Y-1, and H232Y-21 cells following G2/M arrest with nocodazole. These lysates were treated with λPPase for 30 or 60 min. SIRT2 protein in lysates without λPPase treatment contains multiple phosphorylated protein species (Fig. 3E). The λPPase time course suggested that the 51-kDa, slowest-migrating phosphorylated form was the most labile and the protein becomes converted stepwise into the hypophosphorylated 48-kDA isoform (Fig. 3E, lanes 2, 5, and 8). Because the mutant SIRT2 protein appeared to migrate more quickly on SDS-PAGE gels, we investigated the reason for the apparent lower molecular mass than that of the wild-type SIRT2 protein. The entire H232Y construct was sequenced prior to transfection into cells, and except for the single base change engineered to change the amino acid H232Y, the sequence was identical to that of the wild-type construct. To ensure that no unusual processing of the mutant SIRT2 protein was occurring, wild-type and mutant SIRT2 proteins were isolated from lysates of Saos2-transfected cells by using Ni-NTA magnetic agarose beads, which specifically bind to the amino-terminal His tag. When SIRT2 was eluted from the beads with 250 mM imidazole, the wild-type and H232Y mutant proteins were detectable by Western blotting with the SIRT2 antibody, which is specific for the carboxy-terminal 14 aa of the protein (Fig. 3D). Thus, the H232Y protein appeared to be intact, and we concluded that the mutation caused a conformational change in the protein, which accounts for the different electrophoretic mobility from that of the wild-type protein. The targeted His residue in this mutant occurs at the precise point in the three-dimensional structure at which the SIRT2 polypeptide chain winds from the lower Rossmann-fold lobe up into the helical domain centered on a Zn2+ finger (2). Not only is this His essential for catalysis, but changing it from His to Tyr may bring about a destabilization of the three-dimensional structure and thus be reflected in a mobility shift on our conformationally-sensitive SDS-PAGE separations.

Exit from mitosis is slower in cells expressing high levels of SIRT2.

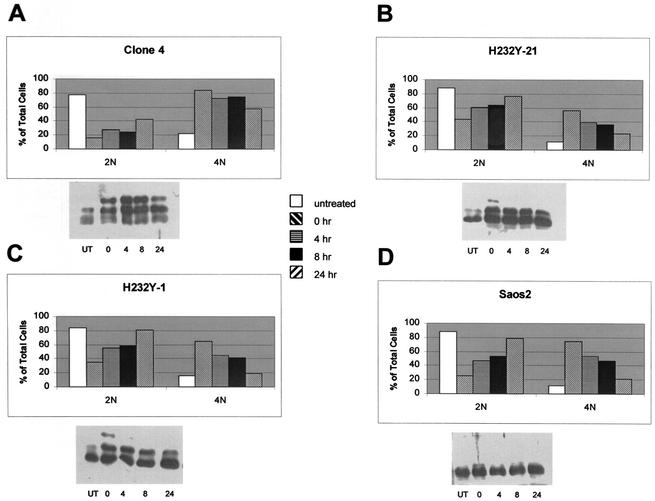

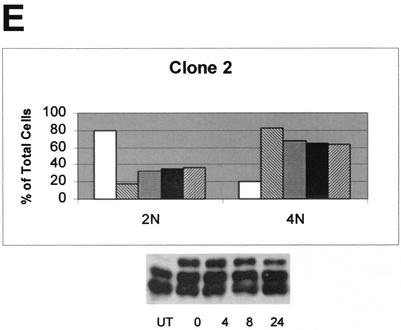

Because nocodazole reversibly blocks cells at the G2/M boundary, when this drug is removed from the culture medium, the cells are able to enter M phase and resume passage through the cell cycle (18). Stable transfectants and the parental Saos2 cell lines were tested for their ability to exit mitosis and enter the cell cycle after release from nocodazole block in M. For this experiment, we did not use a double-thymidine block, but rather, the cells were grown to ∼80% confluency, and then the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing nocodazole. The cells were harvested after 20 h of nocodazole treatment (designated as the 0-h time point) or at the various times after removal of nocodazole from the medium and analyzed by flow cytometry and Western blot analysis (Fig. 4). Following removal of nocodazole from the medium, the parental cell line Saos2, H232Y-1, and H232Y-21 readily resumed the cell cycle and entered into G1, as evidenced by the increase in 2N DNA content after 6 h (Fig. 4B, C, and D). After 24 h, 65 to 80% of the cells had a 2N DNA content. In contrast, even 24 h after removal of nocodazole from SIRT2-overexpressing clone 2 and clone 4 cells, 60 to 65% of the cells remained in G2/M (Fig. 4A and E). Like clone 4, clone 2 overexpressed the phosphorylated SIRT2 isoforms. Clone 6, which expressed little phosphorylated SIRT2 (Fig. 3A, lane 2), behaved similarly to the parental Saos2 cell line after nocodazole block (data not shown). We found that the amount of NDAC activity in clone 4 cells remained at increased levels throughout the 24 h after release from nocodazole block (data not shown). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the presence of phosphorylated SIRT2 isoforms and increased NDAC activity function to delay the exit of cells from mitosis.

FIG. 4.

SIRT2 stable transfectants that overexpress the wild-type phosphorylated forms of SIRT2 return to G1 less effectively than cells expressing mutant SIRT2 or nonhyperphosphorylated cell lines. Cell lines were treated with nocodazole for 20 h, and then the nocodazole was washed out. Cells were collected for flow cytometry at the indicated times after the initiation of nocodazole washout. In panels A to E, graphs indicate the percentage of cells with a 2N and 4N DNA contents at each time point for each cell line. Cell lysates were harvested at each time point and immunoblotted with SIRT2 peptide antibody (results shown below each graph). UT, untreated, unsynchronized cells. These results are representative of those obtained in multiple experiments. The more hyperphosphorylated the cell line is, the slower the exit from mitosis is.

Overexpression of the protein phosphatase CDC14B results in SIRT2 dephosphorylation and a substantial reduction in SIRT2 protein.

Because there appeared to be a correlation between SIRT2 phosphorylation status and exit from mitosis, we sought to identify a phosphatase or kinase that might influence SIRT2 phosphorylation status. It has been reported that the budding yeast Cdc14 dual-specificity phosphatase is sequestered in the nucleolus during most of the cell cycle and becomes active only in mitosis, at which time it dephosphorylates the mitosis-specific kinase Cdc28/Clb as part of the activation of the mitotic exit network (MEN) (15, 32). In humans, there are two genes encoding putative homologs of yeast CDC14. CDC14A is contained in humans at 1p21.2, and CDC14B is contained at 9q22.32 (21). Expression plasmids pEGFP-hCDC14A and pEGFP-hCDC14B, encoding these human CDC14 homologs (20), were transiently transfected into clone 4. Cells were harvested after 48 h, and the abundance of SIRT2 was analyzed by Western blot analysis. Since the CDC14A and -B plasmids were constructed by fusing the CDC14A or -B cDNA to the carboxy terminus of green fluorescent protein (GFP), transfection efficiency could be monitored by the acquisition of green fluorescence. The efficiencies of transfection of CDC14A and -B were both approximately 30% when transfected into clone 4 cells (data not shown). The transfection of CDC14B into clone 4 resulted in a reduction in phosphorylation status of SIRT2 and a significant loss of total SIRT2 protein (Fig. 5B, lane 1). This dramatic reduction in SIRT2 protein was seen when 12 μg of the pEGFP-hCDC14B was transfected into clone 4, and less so after transfection of 6 μg of CDC14B (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, there was little effect on SIRT2 protein when 6 or 12 μg of CDC14A was transfected into clone 4 (Fig. 5A); there may be some dephosphorylation, because there was a slight reduction in the amount of the slowest-migrating phosphorylated species (Fig. 5A, lane 1).

In order to determine whether the dephosphorylation and reduction of SIRT2 protein were due to the phosphatase activity of CDC14B, we constructed a mutant CDC14B protein via site-directed mutagenesis. CDC14B contains the HCXAGXXR(S/T) motif, which is present at the active site of all protein tyrosine and DSP phosphatases (35). A single amino acid substitution of any of the highly conserved C, A, or R residues within this motif results in an inactive phosphatase in yeast (20). The highly conserved cysteine (C) in the active site (codon TGC) was changed to serine (S; codon TCC). The resulting construct (Cdc14B C314S) and the wild-type CDC14B were transiently transfected into clone 4 cells. With increasing DNA concentrations, the wild-type CDC14B dramatically decreased the abundance of SIRT2 protein (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 to 3) in proportion to the amount of DNA transfected, whereas the Cdc14B C314S plasmid had no effect on SIRT2 status at the DNA concentrations examined (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 to 6). Using GFP fluorescence in transfected cells to monitor expression of the Cdc14B C314S protein, we found that the subcellular localization of the Cdc14B C314S protein was identical to that of the wild-type protein. The fact that the wild-type CDC14B, but not the inactive CDC14B mutant, caused the loss of SIRT2 protein suggests that there is a functional link between CDC14B phosphatase activity, SIRT2 phosphorylation, and SIRT2 abundance, consistent with a role for these proteins in mitosis.

Inhibitors of the 26S proteasome allow stabilization of SIRT2 protein.

The budding yeast CDC14 protein is involved in activation of ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic degradation (38, 41). In this system, CDC14p is thought to target proteins via dephosphorylation for subsequent ubiquitination and proteolysis. Lactacystin and epoxomicin are two highly specific inhibitors of the 26S proteasome, a protease complex responsible for most nonlysosomal protein degradation in cells (8, 26). Clone 4 cells were treated for 20 h with 10 μM lactacystin, 10 μM clasto-lactacystin β-lactone (the biologically active form of lactacystin), or 0.1 μM epoxomicin. As a control, Saos2 cells were also treated with epoxomicin. Addition of either class of proteasome inhibitor stabilized all SIRT2 isoforms compared to untreated controls (Fig. 5D, lanes 1 to 7). Because lactacystin and epoxomicin specifically inhibit the catalytic subunits of the proteasome, these results suggested that SIRT2 is targeted for ubiquitination and proteolysis by the 26S proteasome. Clone 4 cells were also transiently transfected with pEGFP-hCDC14B or the CDC14B C314S plasmid and then treated with 0.1 μM epoxomicin. Epoxomicin relieved the effects of CDC14B on SIRT2 degradation (Fig. 5D, lanes 8 and 9). Cells transfected with CDC14B C314S behaved similarly to untransfected clone 4 cells in that little SIRT2 degradation was observed (Fig. 5D, lanes 10 and 11). These results suggest a direct correlation between the CDC14B-induced degradation of SIRT2 protein and the 26S proteasome.

We also directly tested whether SIRT2 is ubiquitinylated by transiently cotransfecting a plasmid containing the HA epitope tag fused 5′ to eight ubiquitin peptide-expressing cDNAs (pMT123) and pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 into Saos2 cells. As a control, cells were cotransfected with pMT123 and pcDNA3.1/HisC empty vector. After 48 h, SIRT2 was isolated either with Ni-NTA magnetic beads or immunoprecipitated with protein A and SIRT2 antibody and analyzed by Western blotting. Antibodies to SIRT2 and to HA were used to detect the SIRT2 levels and to determine whether the protein was ubiquitinylated. Cotransfection of pcDNA3.1-SIRT2 and pMT123 yielded a 57- to 60-kDa band that was not present in control lysates (Fig. 5E). There was some nonspecific background, especially from Ni-NTA isolations, but the predominate ubiquitin-SIRT2 band was not present in the controls (compare Fig. 5E, lanes 1 and 3, with lanes 2 and 4). Upon prolonged exposure of lane 5, a band comigrating with ubiquitinated SIRT2 (about 57 kDa) was visible. In summary, consistent with our observation that proteasome inhibitors affect the stability of SIRT2 and as such it is a ubiquitinylated protein, both immunoprecipitation and Ni-NTA isolations resulted in coassociation of HA-tagged ubiquitin and SIRT2.

Our data are highly suggestive that proteasome-mediated proteolysis of SIRT2 results from the action of CDC14B either directly or indirectly. However, attempts to demonstrate a direct physical interaction between CDC14B and SIRT2 in vitro have failed, although we could readily detect the interaction of CDC14B and p53 (21; F. Nahhas and M. A. Tainsky, unpublished results).

DISCUSSION

Our studies suggest a role for the SIRT2 NDAC in the control of mitotic exit or possibly cytokinesis, a function only recently explored in yeast Sir2 or the metazoan SIRT orthologs. Brachman et al. (5) found that deletion of Hst3 and Hst4 resulted in a delay in cell cycle progression. However, SIRT2 is more closely related to the yeast Hst2 protein, which has not been implicated in cell cycle regulation (5) until very recently. Borra et al. (4) showed that Hst2 delayed or blocked starfish embryonic cell division. In addition, they showed that human SIRT2, as well as Hst2, delays or blocks starfish oocyte maturation. Our studies suggest that one of the two CDC14-like DSPs, namely CDC14B, acts upstream of SIRT2 as a negative regulator, probably by targeting SIRT2 for 26S proteasome-mediated destruction. Consistent with this hypothesis, we detected ubiquitination of SIRT2 and stabilization of SIRT2 by proteasome inhibitors, particularly after CDC14B stimulated SIRT2 protein loss. This interaction of CDC14B with SIRT2 is likely to be indirect, because we have been unable to show a direct interaction between CDC14B and SIRT2 (Nahhas and Tainsky, unpublished). It will be important to identify the pathway of proteins that interact directly with SIRT2 to better understand the role of SIRT2 in progression through mitosis and whether this represents a role for protein acetylation/deactylation in a mitotic checkpoint (42).

The highest levels of expression of SIRT2 are found during mitosis. Using confocal microscopy of asynchronously growing Saos2 cells, we found that SIRT2 increased in abundance at mitosis, coalescing around the mitotic chromatin. Although our data and those of others (1, 29, 43) suggest SIRT2 is cytoplasmic, our results are the first to demonstrate mitotic accumulation of SIRT2 protein. Analysis of Saos2 and overexpressing SIRT2 transfectants revealed that SIRT2 is phosphorylated during mitosis. The inability to detect hyperphosphorylation in Saos2 is due, we believe, to the extremely low abundance of SIRT2 in these cells.

Overexpression of wild-type SIRT2 causes cells to delay reentry into the cell cycle as compared to the parent Saos2 cells or cells overexpressing an NDAC-defective mutant of SIRT2. These data clearly demonstrate that the NDAC activity of SIRT2 is responsible for the delay in mitotic exit. SIRT2 is a class III NDAC that requires NAD as a cofactor for activity (9, 29, 31). Acetylation and deacetylation of proteins involved in cell cycle regulation are well documented (for a recent review, see reference 42). Overexpression of SIRT2 NDAC activity could prevent cells from reentering the cell cycle in a timely fashion by preventing the acetylation of a downstream target or continuously deacetylating a target protein that must be acetylated for mitosis to proceed. The Saos2 cells expressing H232Y SIRT2 resume cell cycling normally after release from nocodazole blockage in mitosis. These mutant SIRT2 proteins are hyperphosphorylated, although not to the extent of the wild-type protein (Fig. 4A and E). As they enter the cell cycle, the phosphorylated isoforms decrease in abundance (Fig. 4B and C), indicating the conformation or activity of the mutant NDAC protein is not affecting its recognition by cellular protein phosphatases. As shown in Fig. 4, clone 4 (panel A) and clone 2 (panel E) retain an abundance of phosphorylated isoforms 24 h post-nocodazole washout. These data also suggest that increased NDAC activity, due to stabilization from proteasome degradation, is the key determinant of the role of SIRT2 in mitotic exit.

The possibility that the phosphorylation of SIRT is a signal in a cascade involved in mitosis is strongly suggested by the functional relationship between CDC14B and SIRT2. When increasing amounts of CDC14B are introduced into SIRT2-overexpressing Saos2 cells, SIRT2 concentrations were reduced. This effect was not seen when CDC14A or a phosphatase-defective mutant of CDC14B was introduced into cells. In addition, the effect of CDC14B on SIRT2 degradation is dose dependent in that as more CDC14B is transfected into cells, less SIRT2 can be detected (Fig. 5C). Our inability to show direct interaction between CDC14B and SIRT2 suggests that either the interaction is very transient or CDC14B is acting as a signal to activate an as-yet-unidentified phosphatase or inhibit a putative SIRT2 protein kinase. In yeast, CDC14 is active only during mitosis and is involved in activation of the mitotic exit network (15, 32). Recent work (24) has shown that both overexpression and down regulation of human CDC14A disrupt centrosome separation and chromosome segregation. These authors demonstrated that CDC14B was localized to the nucleolus and when overexpressed showed little effect on the cell cycle, whereas CDC14A induced apoptosis. Our data implicating CDC14B in mitotic exit would suggest a conservation of function through eukaryotic evolution with as-yet-unknown targets.

The human CDC14A and the yeast Cdc14 phosphatase have both been implicated in the regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex, which mediates the degradation of cell cycle regulators via ubiquitination (3, 35, 38). Since CDC14B promotes the disappearance of SIRT2, the likelihood that ubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome are both involved in SIRT2 turnover is clearly indicated. Therefore, we analyzed the effects of protease inhibitors on the abundance of SIRT2 protein. Lactacystin; its active form, clasto-lactocystin-β-lactone; and epoxomicin have all been shown to be highly potent and specific inhibitors of the 26S proteasome (8, 26). The link between SIRT2 and CDC14B is further suggested by the fact that these proteasome inhibitors stabilize SIRT2. Our observation that SIRT2 is ubiquitinated further supports the notion that CDC14B phosphatase can provoke SIRT2 degradation via the 26S proteasome-dependent pathway. We propose that phosphorylation stabilizes SIRT2 and that CDC1B causes destabilization, thereby controlling the cell cycle-dependent abundance of SIRT2, its NDAC activity, and mitotic exit.

What sense can be made (if any) of the apparent p53-directed function of SIRT1, the developmental regulation of the Drosophila dSir2, and the M phase regulatory function of SIRT2? Could it be that these proteins have acquired a cell cycle regulatory function during metazoan evolution, which focuses an NAD+-dependent deacetylase intrinsic to SIRT protein onto evolutionarily innovative targets enabling diversification of cell cycle parameters that distinguish higher eukaryotes? Both the timing and spatial organization of mitosis in early development are key to the diversification of the patterns of metazoan development. For example, in frogs, flies, and echinoderms, the first 10 to 12 mitotic cycles are rapid and synchronous, are missing the G1 and G2 phases, and regulate the cell cycle at later stages. This occurs in early mammalian embryonic development as well. Spatial diversification of mitosis is also key to taxonomic diversification of embryonic pattern. Unlike insects, both nematodes and echinoderms rapidly institute asymmetric cell divisions in early development, a phenomenon that seems to be enabled in C. elegans by an interplay between astral microtubules and the juxtamembrane cytoskeletal network known as the cortex (11). In addition, the cellular underpinnings of asymmetric mitoses involve asymmetric activity of microtubule-associated molecular motors (dyneins, kinesins, and myosin V) and other microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs), which may regulate “microtubule catastrophe” (27).

How might SIRT2 play into this process? Hyperphosphorylated SIRT2 is confined to M phase in cycling cultured cells, and we believe that SIRT2's enzymatic activity is confined to this period. We hypothesize that a specific acetylated protein target in the spindle apparatus (including the centrosome) is the target of SIRT2, and SIRT2 might provide a continuous level of deacetylation of this target during M phase to counteract a continuous “on-reaction” (i.e., acetylation). Such a partnering of SIRT2 with a spindle apparatus protein not only might result in deacetylation of this spindle protein, but also might provide a distinct subcellular focal source point in the spindle apparatus for generation of the novel metabolite OAAR (34). In this model, CDC14B release late in M phase would spread a wave of CDC14B throughout the cell, thereby removing SIRT2 function. In yeast, Cdc14p is believed to be regulated by its subcellular location. It is sequestered in the nucleolus until its release during early anaphase by the Cdc14 early anaphase release (FEAR) network, and then in late anaphase, the MEN prevents Cdc14p from relocalizing to the nucleolus, as part of this network, Cdc14p dephosphorylates its mitotic cyclin and Cdk targets, allowing reentry into the cell cycle (32, 40). In humans, CDC14A interacts with centrosomes and is involved in correct centrosome separation and chromosome segregation, but no in vivo function has been identified for CDC14B (17, 24). It is tempting to speculate that in humans, CDC14B is in a phosphorylation pathway upstream of SIRT2 and that SIRT2 NDAC activity serves as a late mitotic checkpoint to ensure correct segregation of chromosomes during cytokinesis. Once this function has been served, CDC14B targets SIRT2 for dephosphorylation and ubiquitination, thus turning off SIRT2's NDAC activity and allowing acetylation of a target protein, which would then stimulate transcription of factors required for entry into G1 of the cell cycle. This function of SIRT2 would put it in a parallel pathway to that of SIRT1 and its interactions with p53 (23, 33, 39), wherein SIRT1 deacetylation of p53 is involved in the regulation of the p53 checkpoint induced by DNA damage or stress.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

Recently North et al. showed that the human SIRT2 is an NAD+-dependent tubulin deacetylase and colocalizes with microtubules; these data further support our evidence for a role for SIRT2 in the control of mitosis (B. J. North, B. L. Marshall, M. T. Borra, J. M. Denu, and E. Verdin, Mol. Cell 11:437-444, 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank George Brush for help with the λPPase experiments and gel conditions for separating phosphorylated isoforms of SIRT2 and Gabriel Fenteany for hints on how to use the proteasome inhibitors, as well as Y. Haupt for the use of pMT123. We also thank George Brush and Gen Sheng Wu for critical reading of the manuscript and Judith Abrams for statistical analysis of flow cytometry data.

This work was supported by the Barbara and Fred Erb Endowed Chair in Cancer Genetics to M.A.T.; funds from the Karmanos Cancer Institute; and the Applied Genomics Core, Core Flow Cytometry, Biostatistics Core, and Confocal Microscopy facilities of the Karmanos Cancer Institute and Wayne State University (P30CA022453).

REFERENCES

- 1.Afshar, G., and J. P. Murnane. 1999. Characterization of a human gene with sequence homology to Saccharomyces cerevisiae SIR2. Gene 234:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avalos, J. L., I. Celic, S. Muhammad, M. S. Cosgrove, J. D. Boeke, and C. Wolberger. 2002. Structure of a Sir2 enzyme bound to an acetylated p53 peptide. Mol. Cell 10:523-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bembenek, J., and H. Yu. 2001. Regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex by the dual specificity phosphatase human Cdc14a. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48237-48242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borra, M. T., F. J. O'Neill, M. D. Jackson, B. Marshall, E. Verdin, K. R. Foltz, and J. M. Denu. 2002. Conserved enzymatic production and biological effect of O-acetyl-ADP-ribose by silent information regulator 2-like NAD+-dependent deacetylases. J. Biol. Chem. 277:12632-12641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brachmann, C. G., J. M. Sherman, S. E. Devine, E. E. Cameron, L. Pillus, and J. D. Boeke. 1995. The Sir2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 9:2888-2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, J.-H., H.-C. Kim, K.-Y. Hwang, J.-W. Lee, S. P. Jackson, S. D. Bell, and Y. Cho. 2002. Structural basis for the NAD-dependent deacetylase mechanism of Sir2. J. Biol. Chem. 277:34489-34498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darzynkiewicz, Z., and G. Juan. 1997. DNA content measurement for DNA ploidy and cell cycle analysis, 2nd ed., vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Fenteany, G., and S. L. Schreiber. 1998. Lactacystin, proteasome function, and cell fate. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8545-8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finnin, M. S., J. R. Donigian, and N. P. Pavletich. 2001. Structure of the histone deacetylase SIRT2. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:621-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frye, R. 2000. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273:793-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonczy, P., J. M. Bellanger, M. Kirkham, A. Pozniakowski, K. Baumer, J. B. Phillips, and A. A. Hyman. 2001. zyg-8, a gene required for spindle positioning in C. elegans, encodes a double cortin-related kinase that promotes microtubule assembly. Dev. Cell 1:363-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarente, L. 1999. Diverse and dynamic functions of the Sir silencing complex. Nat. Genet. 23:281-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guarente, L. 2000. Sir2 links chromatin silencing, metabolism, and aging. Genes Dev. 14:1021-1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivy, J. M., A. J. S. Klar, and J. B. Hicks. 1986. Cloning and characterization of four SIR genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:688-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaspersen, S. L., J. F. Charles, R. L. Tinker-Kulberg, and D. O. Morgan. 1998. A late mitotic regulatory network controlling cyclin destruction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:2803-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juan, L. J., W. J. Shia, M. H. Chen, W. M. Yang, E. Seto, Y. S. Lin, and C. W. Wu. 2000. Histone deacetylases specifically down-regulate p53-dependent gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20436-20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser, B. K., Z. A. Zimmerman, H. Charbonneau, and P. K. Jackson. 2002. Disruption of centrosome structure, chromosome segregation, and cytokinesis by misexpression of human Cdc14A phosphatase. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2289-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur, G., M. Stetler-Stevenson, S. Sebers, P. Worland, H. Sedlacek, C. Myers, J. Czech, R. Naik, and E. Sausville. 1992. Growth inhibition with reversible cell cycle arrest of carcinoma cells by flavone L86-8275. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 84:1736-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klar, A. J., S. Fogel, and K. Macleod. 1979. Mar1-A regulator of the HMa and HMa loci in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 93:37-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, L., B. R. Ernsting, M. J. Wishart, D. L. Lohse, and J. E. Dixon. 1997. A family of putative tumor suppressors is structurally and functionally conserved in humans and yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 272:29403-29406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, L., M. Ljungman, and J. E. Dixon. 2000. The human Cdc14 phosphatases interact with and dephosphorylate the tumor suppressor protein p53. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2410-2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, S. J., P. A. Defossez, and L. Guarente. 2000. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 289:2126-2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo, J., A. Y. Nikolaev, S.-I. Imai, D. Chen, F. Su, A. Shiloh, L. Guarente, and W. Gu. 2001. Negative control of p53 by Sir2a promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107:137-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mailand, N., C. Lukas, B. K. Kaiser, P. K. Jackson, J. Bartek, and J. Lukas. 2002. Deregulated human Cdc14A phosphatase disrupts centrosome separation and chromosome segregation. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:317-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBurney, M. W., Y. Yang, K. Jardine, M. Hixon, K. Boekelheide, J. R. Webb, P. M. Lansdorp, and M. Lemieux. 2003. The mammalian SIR2a protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 23:38-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng, L., R. Mohan, B. H. Kwok, M. Elofsson, N. Sin, and C. M. Crews. 1999. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:10403-10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchison, T., and M. Kirschner. 1984. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature 312:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai, K., and P. Horton. 1999. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:34-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perrod, S., M. M. Cockell, T. Laroche, H. Renauld, A. L. Ducrest, C. Bonnard, and S. M. Gasser. 2001. A cytosolic NAD-dependent deacetylase, Hst2p, can modulate nucleolar and telomeric silencing in yeast. EMBO J. 20:197-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg, M. I., and S. M. Parkhurst. 2002. Drosophila Sir2 is required for heterochromatic silencing and by euchromatic Hairy/E(Spl) bHLH repressors in segmentation and sex determination. Cell 109:447-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwer, B., B. J. North, R. A. Frye, M. Ott, and E. Verdin. 2002. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase. PG. J. Cell Biol. 158:647-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shou, W., J. H. Seol, A. Shevchenko, C. Baskerville, D. Moazed, Z. W. Chen, J. Jang, H. Charbonneau, and R. J. Deshaies. 1999. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97:233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, J. 2002. Human Sir2 and the "silencing' of p53 activity. Trends Cell Biol. 12:404-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanny, J. C., and D. Moazed. 2001. Coupling of histone deacetylation to NAD breakdown by the yeast silencing protein Sir2: evidence for acetyl transfer from substrate to an NAD breakdown product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:415-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor, G. S., Y. Liu, C. Baskerville, and H. Charbonneau. 1997. The activity of Cdc14p, an oligomeric dual specificity protein phosphatase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for cell cycle progression. J. Biol. Chem. 272:24054-24063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tissenbaum, H. A., and L. Guarente. 2001. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 410:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toyoshima, F., T. Moriguchi, A. Wada, M. Fukuda, and E. Nishida. 1998. Nuclear export of cyclin B1 and its possible role in the DNA damage-induced G2 checkpoint. EMBO J. 17:2728-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Traverso, E. E., C. Baskerville, Y. Liu, W. Shou, P. James, R. J. Deshaies, and H. Charbonneau. 1931. 2001. Characterization of the net1 cell cycle-dependent regulator of the Cdc14 phosphatase from budding yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21924-21931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaziri, H., S. K. Dessaln, E. N. Eaton, S.-I. Imai, R. A. Frye, T. K. Pandita, L. Guarente, and R. A. Weinberg. 2001. hSir2SIRT1 functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell 107:149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visintin, R., and A. Amon. 2000. The nucleolus: the magician's hat for cell cycle tricks. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:752.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visintin, R., E. S. Hwang, and A. Amon. 1999. Cfi1 prevents premature exit from mitosis by anchoring Cdc14 phosphatase in the nucleolus. Nature 398:818-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, C., M. Fu, S. Mani, S. Wadler, A. M. Senderowicz, and R. G. Pestell. 2001. Histone acetylation and the cell-cycle in cancer. Front. Biosci. 6:D610-D629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang, Y. H., Y. H. Chen, C. Y. Zhang, M. A. Nimmakayalu, D. C. Ward, and S. Weissman. 2000. Cloning and characterization of two mouse genes with homology to the yeast Sir2 gene. Genomics 69:355-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhuo, S., J. C. Clemens, D. J. Hakes, D. Barford, and J. E. Dixon. 1993. Expression, purification, crystallization, and biochemical characterization of a recombinant protein phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 268:17754-17761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]