Abstract

The expression of several genes in Neisseria meningitidis upon contact with epithelial cells was associated with the presence of the contact regulatory elements of Neisseria. These genes are involved in various aspects of meningococcal biology and could be coordinately regulated upon contact with target cells.

Neisseria meningitidis is a gram-negative bacterium of the genus Neisseria. It is an occasional pathogen that provokes septicemia, meningitis, and arthritis in humans. Bacterium-host interaction may require pleiotropic regulatory systems that could act through cis-regulatory promoter elements to coordinate the expression of several genes. Contact regulatory element of Neisseria (CREN) is a 150-bp sequence specific for pathogenic Neisseria species (N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae). It was first described in the promoter regions of pilC1 and crgA genes immediately upstream of the ribosome-binding site (4). CREN is involved in the induction of the transcription of pilC1 and crgA genes upon contact with the target cells. This induction is necessary for optimal adhesion of N. meningitidis to cells (3, 9). CREN harbors a transcription start point preceded by a GG-N8-(A/G)C motif where the GG doublet was required for the induction of the expression of pilC1 (9). PilC1 is required for type IV pilus assembly and adhesion of bacteria to target cells (6). CrgA is a transcriptional regulator that is involved in the switch of bacterial adhesion to intimate adhesion through downregulation of capsule, pilC1, and pili (3, 4). Binding of CrgA to target promoters is independent from the presence of the CREN element. Indeed CrgA-binding sites are located upstream of the CREN element (in pilC1). CrgA also binds to promoters of the pilE and sia genes that are devoid of CREN elements (3, 4). A probe corresponding to CREN of pilC1 of the strain 8013 was able to hybridize to several chromosomal loci in several strains of N. meningitidis from different genetic lineages (4). Moreover, several copies of CREN homologs are present in the published complete genomes of two meningococcal strains (7, 11). We aimed in this work to explore the involvement of new CREN-like elements in the regulation of gene expression upon contact with target cells.

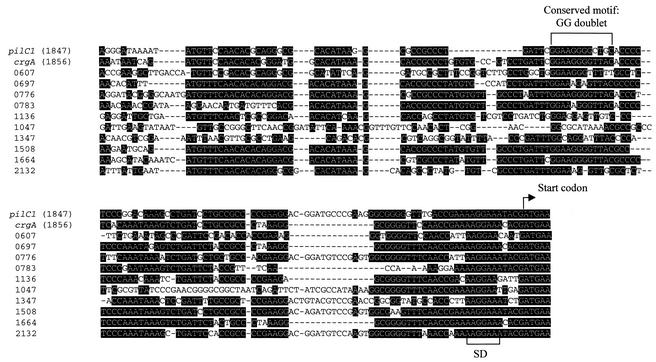

In silico analysis of strain MC58 (serogroup B) (http://www.tigr.org) revealed that different loci showed homology to CREN of pilC1. The sequence identity ranged between 58.5 and 97.4% (Fig. 1). Similar observations were made with the strain Z2491 (serogroup A) (http://www.sanger.ac.uk). CREN corresponds to the repeat element (Rep2) that was described on the complete genomic sequence of N. meningitidis (7). We selected 12 loci on the basis of the presence of an open reading frame (ORF) downstream of these CREN homologs in the strain MC58 (Table 1). All CREN elements from these loci showed a GG-N8-(A/G)C-related motif in comparison to pilC1 and crgA (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of nucleotide sequences of CREN elements of the 12 genes identified in this work. The start codons of the ORFs and the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (SD) are indicated. The conserved GG doublet is also shown. Black background indicates conserved bases.

TABLE 1.

CREN-harboring genes and their characteristics

| Locus in MC58 | CREN (% identity)a | Homology | Predicted size (amino acids) of protein | Presence of ORF in:

|

Presence of CREN in N. meningitidis strainsb | Induction of expression in 8013 strain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains of N. meningitidisb | Nonpathogenic Neisseriac | ||||||

| NMB0607 | 58.5 | secD protein, export membrane protein | 618 | + | + | Not determined | Not determined |

| NMB0697 | 66 | ksgA dimethyl adenosine transferase involved in protein synthesis | 259 | + | − | + | + |

| NMB0776 | 73.1 | gly1 of N. gonorrhoeae; effect on cytotoxicity | 139 | + | +d | +e | + |

| NMB0783 | 60 | No hmology | 159 | + | +d | +f | −h |

| NMB1047 | 59.9 | No homology | 123 | + | +d | + | + |

| NMB1136 | 61 | No homology | 184 | + | + | + | + |

| NMB1347 | 68.5 | suhB extragenic suppressor protein | 261 | + | − | + | + |

| NMB1508 | 77.1 | No homology | 472 | + | − | + | + |

| NMB1664 | 68.4 | Peptidase family U32 | 451i | + | +d | + | + |

| NMB1847 | 97.4 | pilC1; adhesion and pilus assembly | 1,028 | + | − | + | + |

| NMB1856 | 68.5 | crgA; regulation of adhesion | 299i | + | − | + | + |

| NMB2132 | 74.8 | Related to transferrin-binding protein | 493 | + | +d | +g | −h |

Percentage of identity to the CREN element of pilC1 gene from the 8013 strain.

Strains of N. meningitidis tested were LNP10817 (serogroup A); LNP16645, LNP16646, LNP14912, and MC58 (serogroup B); LNP18012, 290/94, and 8013 (serogroup C), and LNP17617 and LNP18399 (serogroup W135).

Nonpathogenic Neisseria strains were N. lactamica LNP411, N. denitrificans LNP412, N. animalis LNP413, N. flavescens LNP414, N. flava LNP3264, and N. sicca LNP3265.

ORF was absent from some strains belonging to nonpathogenic Neisseria species (N. denitrificans strain LNP412, N. animalis strain LNP413, and N. flava strain LNP 3264.

The CREN element was of a higher size in strains LNP18012, 290/94, LNP17617, and LNP18399.

The CREN element was only present in strains LNP16645, LNP16646, LNP14912, and MC58 (serogroup B).

The CREN element was only present in strains LNP14912 and MC58 (serogroup B, ET-5 clonal complex).

Absence of CREN in 8013 strain.

Signal sequence.

Two of the 12 selected loci corresponded to two known genes in N. meningitidis. The first gene was pilC1 (NMB1847), and the second gene was crgA (NMB1856) (Table 1). As for the other 10 loci, 1 (NMB0776) corresponded to the gly1 gene that has been identified in N. gonorrhoeae (1). Another locus (NMB2132) showed homology to transferrin-binding proteins. Four other loci showed homologies to known genes in other bacterial species, and four loci showed no homology to the proteins in the sequence data bank (8, 12, 13) (Table 1).

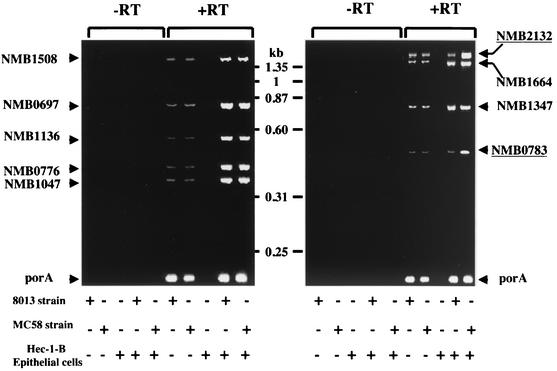

We studied the conservation of these genes among 10 different strains of N. meningitidis from different genetic lineages and serogroups. Oligonucleotides were designed to amplify entirely each ORF from the MC58 strain (Table 2). Forward oligonucleotides (coding strand) start at the ATG codon, while reverse oligonucleotides (noncoding strand) start immediately upstream of the stop codon of each ORF. PCR amplification using these oligonucleotides showed that these genes were present in all tested meningococcal strains (Table 1). For one locus corresponding to NMB0607 in the MC58 strain, no amplification was obtained from strain 8013, but Southern hybridization using the entire PCR product corresponding to the NMB0607 ORF from the strain MC58 as a probe confirmed the presence of this locus in strain 8013 (data not shown; Table 1). The absence of PCR amplification may be due to the DNA polymorphisms between strains MC58 and 8013 in the sequences binding to the oligonucleotides. The same analysis revealed that the presence of these genes was variable among six strains belonging to six different species of nonpathogenic Neisseria (Table 1). Next, we tested whether genes from these different meningococcal strains harbored the CREN element in their promoter regions. Oligonucleotides were designed to amplify the promoter regions of genes from the MC58 strain except for NMB0607. Oligonucleotides at the 5′ side were upstream from each CREN element, whereas the oligonucleotides at the 3′ side were designed immediately downstream from the start codon of each ORF (Table 2). The expected size of PCR products corresponding to different loci was 400 bp. All tested strains revealed PCR fragments identical in size to the fragments from the strain MC58 for the loci corresponding to NMB1047, NMB1136, NMB1347, NMB1508, and NMB1664 as well as crgA and pilC1. DNA sequencing confirmed the presence of CREN elements in these loci in strain 8013. For the locus NMB0776, PCR-amplified fragments of a larger size than that of the strain MC58 was obtained for few strains (550 and 400 bp, respectively) (Table 1). DNA hybridization using the CREN element of pilC1 as a probe confirmed the presence of CREN homologs in these strains. Moreover, DNA sequencing of the PCR fragment obtained from strain 8013 verified the presence of CREN elements. For two loci corresponding to NMB0783 and NMB2132, PCR fragments from all the strains (except for strains LNP14912 and MC58, which are of serogroup B and belong to the ET-5 clonal complex) were smaller than that from the MC58 strain (250 and 400 bp, respectively). However, homologs to the locus NMB2132 (but not to the locus NMB0783) from other serogroup B strains belonging to other genetic lineages showed a smaller promoter region than that of MC58 and LNP14912 strains. DNA sequencing of the PCR fragments obtained from strain 8013 further confirmed the absence of CREN elements in the two loci corresponding to NMB0783 and NMB2132 (Table 1). We next monitored the expression of the genes identified in this work during bacterial adhesion to target cells. Hec-1-B epithelial cells were infected by strain 8013 or MC58 as previously described (4). Total RNA was prepared from the same number of bacteria for both strains from cell-associated bacteria and bacteria grown alone in cell culture medium in the absence of Hec-1-B cells. Bacteria were counted under microscopy using a Petroff-Hausser counting chamber (Touzart & Matignon). Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was performed as previously described (3). In order to prevent the RT-PCR from being saturated, we first standardized the assays using the abundantly expressed porA gene that lacks a CREN element and that is not induced. RT-PCR was performed using 1, 2, 5, 7, and 10 μg of total RNA. The increase of the signal was linear up to 5 μg (data not shown). RT-PCR assays were subsequently performed using 5 μg of total RNA. After 1 h of adhesion, the expression of loci corresponding to NMB0697, NMB0776, NMB1047, NMB1136, NMB1347, NMB1664, and NMB1508 was higher in cell-associated bacteria (Fig. 2). However, no induction of the transcription was detected in the strain 8013 for the genes corresponding to NMB0783 and NMB2132 (devoid of CREN element in their promoter regions in strain 8013). By contrast, these two genes were induced in the MC58 strain (Fig. 2). These results reinforce the association between the CREN element and the induction of the transcription upon contact with target cells.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| ORF purpose and name | Sequence | Relevant characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| ORF amplification | ||

| 0607-1 | 5′-ATGATGAACCGTTATCCTTTATGGAAA-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0607-2 | 5′-CTCCTTGCCTCCTGCCATTTC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 0697-1 | 5′-ATGAAAGAACACAAAGCCCGCAAG-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0697-2 | 5′-GACGACCTTGCCCGCCAGATA-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 0776-1 | 5′-ATGAAAAAAATGTTCCTTTCTGCC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0776-2 | 5′-GGAAAAATCGTCATCGTTGAAATT-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 0783-1 | 5′-ATGAAACACATACTCCCCCTGATT-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0783-2 | 5′-TTCGCCTACGGTTTTTTGTATCAG-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1047-1 | 5′-ATGAATAAAACCTTGTCTATTTTGCCG-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1047-2 | 5′-GCGGTACAGGTGTTTGAAGCA-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1136-1 | 5′-ATGAACAATATGTTTGCCG-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1136-2 | 5′-CTATACTTTTAGGGCGAC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1347-1 | 5′-ATGAATCCGTTTTTGAATACAGCC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1347-2 | 5′-AACGTGTGCGGAAATGATTTTCAA-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1508-1 | 5′-ATGAATATTCACACCCTGCTCTCC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1508-2 | 5′-TTTGATTTTGAAGTTCAGCCAGGC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1664-1 | 5′-ATGAAAGCACCCGAACTCTTATTG-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1664-2 | 5′-GGGTTCAACACGCGTGCGAT-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 2132-1 | 5′-ATGAAGGAGATGATGATGTTTAAACGCAGC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 2132-2 | 5′-ATCCTGCTCTTTTTTGCCGGC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| porA0 | 5′-GATGTCAGCCTATACGGCGAAATCAAA-3′ | Coding strand |

| porA101 | 5′-GCCGATAAACGAGCCGAAATC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| CREN element amplification | ||

| 0697-3 | 5′-CTTCGGCGGCAACACGGGATCGAA-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0697-4 | 5′-CTGCCCGAAACGCTTGCGGGC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 0776-3 | 5′-CGTTGCCGACGCGCGTGCCCA-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0776-4 | 5′-CAGCCGACAGAAGCAATACGGCAG-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 0783-3 | 5′-CGTGCCGAAGCCGCCCTTCAA-3′ | Coding strand |

| 0783-4 | 5′-CGGATGCGGCAATCAGGGGGA-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1047-3 | 5′-CGTGTTGATACCCGCAGTAGGTTT-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1047-4 | 5′-CCGAGTAAGATTGCCACCGGC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1136-3 | 5′-CGTCGTCAAATTCGGGCAATGCCA-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1136-4 | 5′-AACCAGTTTGGACAATTTTGCGGC-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1347-3 | 5′-CATTGTTTTCATCGCGCGCGCGGC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1347-4 | 5′-TGACCGGCACGGCGGGCGGCT-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1508-3 | 5′-CATTCCCCTTTTCCCGCCCCT-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1508-4 | 5′-CCATTGTTTGGAGAGCAGGGTGTG-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 1664-3 | 5′-CGATTTTAGGATTCATCACATTCTCTC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 1664-4 | 5′-CGCCGGCGGGCAATAAGAGTT-3′ | Noncoding strand |

| 2132-3 | 5′-CATTATCGGCGTGATTCAGGATTC-3′ | Coding strand |

| 2132-4 | 5′-GCCATTGCGATTACGCTGCGTTTA-3′ | Noncoding strand |

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR analysis of the expression of different genes identified in this study. Oligonucleotides used amplified the entire ORF for each gene (Table 2). We used oligonucleotides porA0-porA101 to amplify the porA gene as a control (Table 2). Total RNA was extracted from strains 8013 and MC58 that were grown alone in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL), from noninfected Hec-1-B epithelial cells, and from cell-associated bacteria. Monolayers of Hec-1-B epithelial cells were infected by centrifugation as described previously (3), and the RT-PCR analysis was performed after 1 h of infection. RT was from Promega. The two genes (NMB0783 and NMB2132) that were only induced in the MC58 strain are underlined. Size markers are also shown.

The presence of the CREN element for the NMB2132 locus only in strains belonging to the clonal complex ET-5 needs to be confirmed in a larger collection of strains. However, it may be responsible for a physiological polymorphism caused by a differential gene expression pattern upon contact with target cells. Such a polymorphism may provoke a distinct behavior for these strains that are thought to be virulent but with low transmissibility (2). The initial events occurring upon contact of N. meningitidis to target cells at the nasopharynx appear to be crucial in establishing effective colonization (and subsequent invasion of internal compartments) or shedding and dissemination to other hosts (10).

CREN elements seem to control various genes (contact regulon) that are involved in several aspects of the meningococcal biology (metabolism, adhesion, and transcriptional regulation). The molecular signals recognized by N. meningitidis upon contact with target cells and the regulatory proteins involved in signaling pathways have not yet been identified. Other contact-regulated genes have been recently reported using a DNA microarray technique, suggesting that several contact-inducing mechanisms may exist (5). Their interference with CREN-associated genes remains to be analyzed. The pattern of coordinate expression of bacterial genes harboring CREN elements may permit an optimal physiological status enabling either colonization or transmission between hosts.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jean-Michel Alonso for constant support and encouragement.

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Arvidson, C. G., R. Kirkpatrick, M. T. Witkamp, J. A. Larson, C. A. Schipper, L. S. Waldbeser, P. O'Gaora, M. Cooper, and M. So. 1999. Neisseria gonorrhoeae mutants altered in toxicity to human fallopian tubes and molecular characterization of the genetic locus involved. Infect. Immun. 67:643-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartwright, K. (ed.). 1995. Meningococcal disease, p. 115-146. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 3.Deghmane, A. E., D. Giorgini, M. Larribe, J.-M. Alonso, and M.-K. Taha. 2002. Down-regulation of pili of Neisseria meningitidis upon contact with epithelial cells is mediated by CrgA regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1555-1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deghmane, A. E., S. Petit, A. Topilko, Y. Pereira, D. Giorgini, M. Larribe, and M.-K. Taha. 2000. Intimate adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial cells is under the control of the crgA gene, a novel LysR-type transcriptional regulator. EMBO J. 19:1068-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grifantini, R., E. Bartolini, A. Muzzi, M. Draghi, E. Frigimelica, J. Berger, G. Ratti, R. Petracca, G. Galli, M. Agnusdei, et al. 2002. Previously unrecognized vaccine candidates against group B meningococcus identified by DNA microarrays. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:914-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassif, X., J-L. Beretti, J. Lowy, P. Stenberg, P. O'Gaora, J. Pfeifer, S. Normark, and M. So. 1994. Roles of pilin and PilC in adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3769-3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkhill, J., M. Achtman, K. D. James, S. D. Bentley, C. Churcher, S. R. Klee, G. Morelli, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, et al. 2000. Complete DNA sequence of a serogroup A strain of Neisseria meningitidis Z2491. Nature 404:502-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pugsley, A. P., M. G. Kornacker, and I. Poquet. 1991. The general protein-export pathway is directly required for extracellular pullulanase secretion in Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Microbiol. 5:343-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taha, M.-K., P. C. Morrand, Y. Pereira, E. Eugene, D. Giorgini, M. Larribe, and X. Nassif. 1998. Pilus-mediated adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis: the essential role of cell contact-dependent transcriptional upregulation of the PilC1 protein. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1153-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taha, M.-K., A. E. Deghmane, A. Antignac, M. L. Zarantonelli, M. Larribe, and J. M. Alonso. 2002. The duality of Virulence and transmissibility in Neisseria meningitidis. Trends Microbiol. 10:376-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tettelin, H., N. J. Saunders, J. Heidelberg, A. C. Jeffries, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, K. A. Ketchum, D. W. Hood, J. F. Peden, R. J. Dodson, et al. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B strain MC58. Science 287:1809-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Buul, C. P., and P. H. van Knippenberg. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the ksgA gene of Escherichia coli: comparison of methyltransferases effecting dimethylation of adenosine in ribosomal RNA. Gene 38:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano, R., H. Nagai, K. Shiba, and T. Yura. 1990. A mutation that enhances synthesis of sigma 32 and suppresses temperature-sensitive growth of the rpoH15 mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:2124-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]