Abstract

The pentameric form of the cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) is known to be a strong mucosal adjuvant and stimulates antigen-specific secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) and systemic antibody responses to antigens when given by mucosal routes. To deliver CTB for prolonged periods of time to the respiratory mucosa, we constructed a Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) strain that produces and secretes assembled pentameric CTB. Mice immunized intranasally (i.n.) with recombinant BCG (rBCG) developed a stronger anti-BCG IgA response in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF) than mice immunized with nonrecombinant BCG. The total IgA response in the BALF of mice immunized with rBCG was also stronger than that in BALF of mice immunized with the nonrecombinant strain. The induction of IgA was well correlated with an increased production of transforming growth factor β1. Simultaneous administration of intraperitoneally delivered ovalbumin and of i.n. delivered CTB-producing BCG induced a long-lasting ovalbumin-specific mucosal IgA response as well as a systemic IgG response, both of which were significantly higher than those in mice immunized with nonrecombinant BCG together with ovalbumin. These results suggest that the CTB-producing BCG may be a powerful adjuvant to be considered for future mucosal vaccine development.

The mucosal surfaces of the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts represent the principal portal of entry for most human pathogens (19). They contain a variety of cell populations involved in the induction and maintenance of immune responses. CD4+ as well as CD8+ lymphocytes may represent up to 80% of the entire mucosal lymphoid cell population. In addition, the mucosa also contains a variety of immune effector molecules, including antibodies. Secretory immunoglobulin A (IgA) is the major antibody isotype in external secretions (19). Because the induction of IgA responses may offer specific protection against many respiratory, enteric, and genital infections, the development of vaccines for mucosal use provides an attractive possibility for immunization against these infections. To date only a few vaccines, including oral polio vaccine and adenovirus, rotavirus, cold-adapted influenza virus, Salmonella enterica, and cholera vaccines, have become available for administration by mucosal routes (1, 2, 16).

As antigens delivered by the mucosal routes are usually less immunogenic than antigens delivered systemically, mucosal adjuvants are generally needed to obtain effective levels of immune responses after mucosal antigen delivery. Among the strategies to enhance mucosal immunization, the use of cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) as a mucosal adjuvant appears to be particularly promising (9). CTB is structured as a pentamer composed of five identical subunits and represents the receptor-binding moiety of the holotoxin (8, 34). Although the holotoxin is considered the most potent mucosal adjuvant known, its toxicity prevents it from being used as such in vaccine strategies. However, CTB, even in the absence of the toxicity-inducing A subunit, also expresses powerful mucosal adjuvant activity (27). Enteric administration of CTB together with antigens increases antigen-specific mucosal IgA responses (21), and oral or intranasal (i.n.) administration of CTB as a carrier conjugated to an antigen leads to the induction of local antigen-specific secretory IgA responses (26, 33). CTB-mediated IgA isotype switching appears to be controlled by transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) (10).

However, CTB administration by the oral route leads to its rapid elimination in the feces or to its inactivation by mucosal enzymes and the bacterial flora. The use of live bacterial vectors designed to deliver recombinant CTB to the mucosa may represent an attractive approach to improving mucosal vaccination by the induction of long-lasting IgA responses (4, 15, 16, 18, 25, 26), especially if the vectors have the ability to persist for prolonged periods of time. Mycobacterium bovis BCG, one of the most widely used live vaccines, has the ability to persist for several months to years after administration, and its use as a delivery system for heterologous antigens by mucosal routes has attracted considerable interest (20). As BCG is derived from a respiratory pathogen, it is particularly well adapted for the delivery of antigens and/or immunomodulatory molecules by i.n. administration (12, 14). With the aim of developing live delivery systems able to enhance mucosal immunity, we generated a CTB-producing BCG strain. We describe here its construction and the influence of CTB production on antigen-specific IgA responses elicited after either i.n. or intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of the CTB-producing BCG as well as on the local production of TGF-β1.

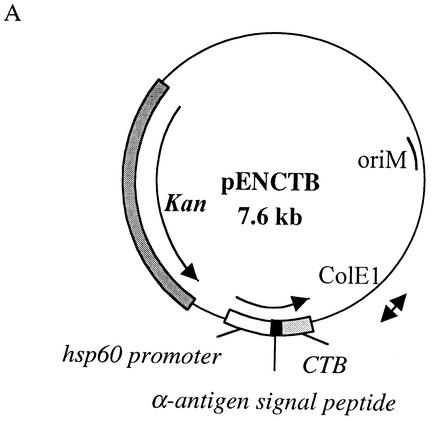

The M. bovis BCG vaccine strain 1173P2 (World Health Organization, Stockholm, Sweden) was genetically modified to produce and secrete CTB by transformation with pENCTB (Fig. 1A), a pRR3 derivative (22) containing the CTB-encoding gene under the control of the BCG hsp60 promoter and modified by replacing the original CTB signal peptide coding sequence with the mycobacterial signal peptide coding sequence from the BCG α-antigen. The 337-bp DNA fragment encoding the mature portion of CTB was amplified by PCR using pTCT1 (3) as the template and the primers 5′-TATAGGATCCACACCTCAAAATATTACTGATTTGT-3′ and 5′-TATAGGTACCATATCTTAATTTGCCATACTAATTG-3′ (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium). The 126-bp DNA fragment encoding the α-antigen signal sequence was amplified by PCR using chromosomal BCG DNA extracted as described previously (11) with the primers 5′-GGCACAGGTCATGACAGACGTGAGCCGAAAGATTCGA-3′ and 5′-GCCGGGATCCCGCGCCCGCGGTTGCCGCTCCGCC-3′ (Eurogentec). The hsp60 promoter was isolated from pUC::hsp60 (11). The production of CTB by the recombinant BCG (rBCG) was analyzed by immunoblotting on mycobacterial cell extracts prepared as described earlier (13), with rabbit anti-CTX (CTA and CTB) antibodies (Sigma) and anti-rabbit antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase. As shown in Fig. 1B, an immunoreactive protein of the expected size was present in the lysate of rBCG (Fig. 1B, lane 3) and was not found in the lysate of untransformed BCG (Fig. 1B, lane 2), indicating that the hsp60 promoter is able to drive expression of the CTB gene in rBCG. The fact that the recombinant CTB comigrated with CTB from purified holotoxin (Fig. 1B, lane 1) suggested that the pre-CTB was totally converted into the mature CTB form and that the α-antigen signal peptide was cleaved off in the rBCG.

FIG. 1.

Production of CTB by rBCG. (A) Structure of pENCTB used for the production and secretion of CTB by rBCG. Dark grey box, kanamycin resistance gene (Kan); ColE1 and oriM, origins of replication from pUC18 and pRR3, respectively; white box, expression cassette containing the BCG hsp60 promoter, the ribosome binding site, and the hsp60 translational initiation codon; black box, α-antigen signal peptide coding sequence; light grey box, CTB coding sequence. (B) Immunoblot analysis of rBCG producing CTB. Lane 1, 100 ng of purified CTX (CTA and CTB); lanes 2 and 3, whole-cell extracts of untransformed BCG and rBCG(pENCTB), respectively. Membranes were probed with a rabbit anti-CTX antibody, followed by incubation with an anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase.

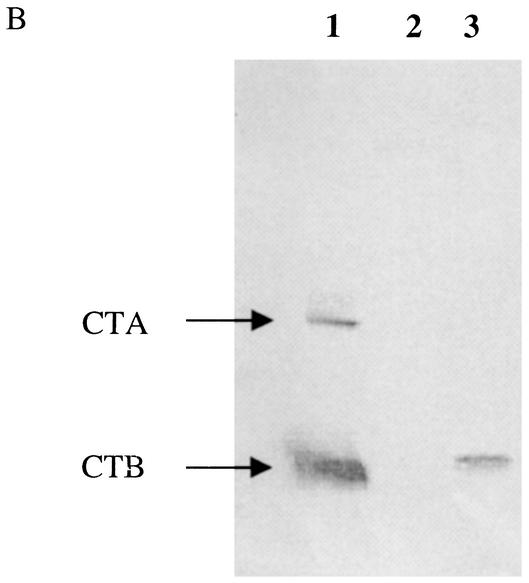

To estimate the amounts of assembled CTB produced by the recombinant strain, a GM1 ganglioside-binding assay was used as reported earlier (5, 24). Only CTB assembled into pentamers is able to bind to the GM1 ganglioside (24). As shown in Fig. 2, assembled CTB can readily be detected in bacterial lysates and in nonconcentrated culture supernatants of rBCG, whereas it is absent in the lysates or culture supernatants from nonrecombinant BCG. Each CTB subunit contains a single intramolecular disulfide bond that is essential for the assembly of the B subunits into the pentamer (7). Consistently, the addition of the reducing agent dithiothreitol to the GM1 ganglioside-binding assay mixture substantially reduced the binding of CTB present in the rBCG lysate and culture supernatant to the ganglioside (Fig. 2). These results indicate that CTB present in cell extracts or in the culture supernatants of the rBCG is pentameric, as it is when naturally produced by Vibrio cholerae (5). This is particularly important, since only pentameric CTB is known to express its mucosal adjuvant activities (24).

FIG. 2.

GM1 ganglioside binding of CTB produced by rBCG. The ability of CTB produced by rBCG to bind to the GM1 ganglioside was analyzed by a GM1 ganglioside ELISA of whole-cell extracts (lanes 1 to 4) or culture supernatants (lanes 5 and 6) from nonrecombinant BCG (lanes 1 and 2) or rBCG (lanes 3 to 6) in the presence or absence of dithiothreitol (DTT) as indicated.

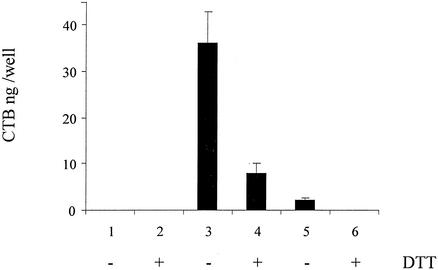

To evaluate the effect of the CTB production by rBCG on the ability to induce antigen-specific IgA in murine bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALF), the levels of anti-BCG IgA were measured in BALF over a 4-month period. Groups of five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice (Iffa Credo, l'Arbresle, France) were i.p. or i.n. immunized with 5 × 106 BCG cells in a final volume of 100 or 40 μl, respectively. Control groups received phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Two months after the first immunization, the mice were given a booster immunization in the same way. The sera and BALF from five mice per group were collected at various time points after the first or the second immunization. The results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that the BALF from mice immunized with rBCG contained significantly more anti-BCG IgA than those from mice that had received nonrecombinant BCG. More importantly, the anti-BCG IgA persisted substantially longer in the BALF from rBCG-immunized mice than in the BALF from the mice immunized with the nonrecombinant strain. Since the growth kinetics of the two BCG strains in vivo in the murine model did not differ (data not shown), the enhanced ability of rBCG to induce IgA responses could not be ascribed to longer persistence and is therefore most likely due to the pharmacological effects of the recombinant CTB. CTB produced by rBCG is thus able to further enhance the natural ability of BCG to induce mucosal immune responses, especially with respect to the duration of the mucosal immune response. In addition to the enhanced IgA responses in BALF, the rBCG also enhanced systemic IgG responses after either i.n. or i.p. immunization (data not shown). These findings suggest that BCG strains producing CTB may constitute attractive mucosal vaccine vehicles able to induce both mucosal and systemic immune responses.

FIG. 3.

Anti-BCG IgA responses in BALF elicited after i.n. immunization with rBCG. BALB/c mice were immunized i.n. with 5 × 106 cells of either nonrecombinant BCG (open circles) or rBCG (black squares) and given a booster immunization 60 days later in the same way. The BALF from each group were collected at the indicated time points and individually analyzed by ELISA for the presence of anti-BCG IgA antibodies. Arrows, times of the first immunization and boosting. ∗, significant difference. Statistical significance was estimated by using the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05).

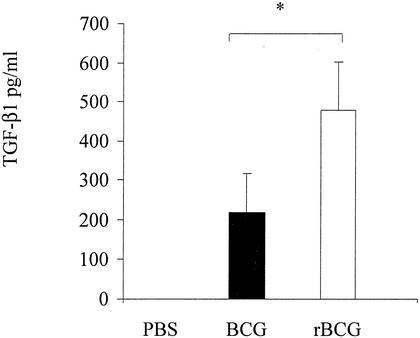

Since TGF-β1 is known to be involved in CTB-induced IgA switching (10), we measured the amounts of TGF-β1 in BALF from mice immunized with the recombinant BCG strain. Mice were sacrificed 2, 59, 66, 96, and 120 days after immunization. For each time point, the BALF from five mice were collected by washing their lungs by lavage with 500 μl of PBS inserted through the trachea of the sacrificed mice. The BALF were then assessed for the presence of cytokines by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (13). The anti-TGF-β1 antibodies (clone 1D11 for capture and WS09 for detection) used for the detection were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, Calif.) and used as recommended by the supplier. The results illustrated in Fig. 4 indicate that, in agreement with previous studies (6, 31), 120 days after the first administration, BCG induced substantial amounts of TGF-β1, whereas no TGF-β1 was detected in the BALF from the control mice that had received PBS. Interestingly, the BALF from mice immunized with the CTB-producing BCG contained approximately twice as much TGF-β1 as the BALF from mice that had received the control strain. TGF-β1 has been described as a major cytokine involved in the induction of mucosal tolerance (32), which may explain the ability of CTB to enhance oral tolerance for coupled proteins (17, 27, 29, 30). Although these observations are consistent with the possibility that the enhanced IgA production induced by rBCG over that induced by nonrecombinant BCG is related to the increase in TGF-β production, we cannot rule out the possibility that the enhanced immune responses observed after rBCG administration may be due to better uptake by antigen-presenting cells.

FIG. 4.

Secretion of TGF-β1 after i.n. administration of rBCG or nonrecombinant BCG. BALB/c mice were immunized i.n. with 5 × 106 cells of either nonrecombinant BCG (black bar) or rBCG (white bar) or received PBS (left) and were boosted 60 days later in the same way. BALF from each group of mice were collected and analyzed by ELISA for the presence of TGF-β1. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. ∗, significant difference. Statistical significance was estimated by using the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05).

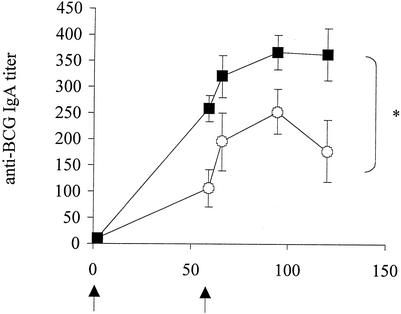

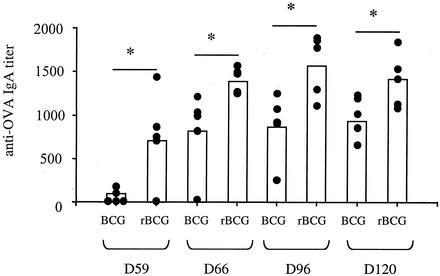

To study the effect of CTB-producing BCG on the immune responses induced against nonrelevant soluble antigens, we coadministered the model antigen ovalbumin (OVA) i.p. along with the BCG strains. The i.p. administration of OVA was chosen because preliminary experiments indicated that coadministration of BCG with OVA by the i.n. route resulted in suffocation of the mice, due to the viscosity of the suspension. Mice received 5 × 106 BCG cells i.n. together with 1 μg of OVA (Sigma) in 100 μl i.p., with alum as the adjuvant. After a booster dose was given 60 days later in the same way, the anti-OVA IgA responses in the BALF were analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5, mice that had received the rBCG developed a strong specific mucosal anti-OVA IgA response, which was significantly higher than that in mice that had received the nonrecombinant BCG. No anti-OVA antibodies could be detected when OVA was administered i.p. without i.n. administration of BCG (data not shown). Administration of a BCG strain containing the empty vector without the CTB-encoding gene showed effects indistinguishable from those observed with the nonrecombinant BCG, indicating that the enhanced IgA response observed after coadministration of rBCG is due to the production of CTB. CTB-producing BCG may thus represent an interesting tool for inducing specific mucosal immune responses against foreign protective antigens. The ability of CTB delivered to the mucosa to enhance protective immunity by coupling to protein antigens has been documented in several models (9), including those involving immunization against schistosomal chronic infections with CTB conjugated to Schistosoma mansoni Sm28GST (28) and immunization against Helicobacter pylori infection with CTB coupled to heparan sulfate-binding proteins (23). Therefore the development of recombinant BCG strains simultaneously producing CTB and heterologous antigens may be useful for inducing protective immunity against bacteria, virus, or parasites present at mucosal surfaces. However, before rBCG strains can be given as i.n. delivery vehicles, important safety issues need to be addressed, such as the risk of inducing meningitis or other neurological or respiratory illnesses.

FIG. 5.

Mucosal immune responses elicited after coinjection of OVA along with BCG. BALB/c mice were immunized i.n. with 5 × 106 cells of either nonrecombinant BCG (BCG) or CTB-producing BCG (rBCG) in the presence of OVA given i.p. and were given a booster immunization 60 days later in the same way. BALF from each group of mice were collected and individually analyzed by ELISA for the presence of anti-OVA IgA antibodies. ∗, significant difference. Statistical significance was estimated by using the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Holmgren for useful discussion.

This work was supported by Institut Pasteur de Lille, INSERM, Région Nord-Pas de Calais, and an EU grant (QLRT-PL 1999-01093).

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Caceres, V. M., and R. W. Sutter. 2001. Sabin monovalent oral polio vaccines: review of past experiences and their potential use after polio eradication. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:531-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin, S. E., and P. A. Offit. 1998. Induction of mucosal B-cell memory by intramuscular inoculation of mice with rotavirus. J. Virol. 72:3479-3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glineur, C., and C. Locht. 1994. Importance of ADP-ribosylation in the morphological changes of PC12 cells induced by cholera toxin. Infect. Immun. 62:4176-4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajishengallis, G., E. Harokopakis, S. K. Hollingshead, M. W. Russell, and S. M. Michalek. 1996. Construction and oral immunogenicity of a Salmonella typhimurium strain expressing a streptococcal adhesin linked to the A2/B subunits of cholera toxin. Vaccine 14:1545-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy, S. J., J. Holmgren, S. Johansson, J. Sanchez, and T. R. Hirst. 1988. Coordinated assembly of multisubunit proteins: oligomerization of bacterial enterotoxins in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:7109-7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Pando, R., H. Orozco, K. Arriaga, A. Sampieri, J. Larriva-Sahd, and V. Madrid-Marina. 1997. Analysis of the local kinetics and localization of interleukin-1 alpha, tumour necrosis factor-alpha and transforming growth factor-beta, during the course of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. Immunology 90:607-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirst, T. R., and J. Holmgren. 1987. Conformation of protein secreted across bacterial outer membranes: a study of enterotoxin translocation from Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:7418-7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmgren, J. 1981. Actions of cholera toxin and the prevention and treatment of cholera. Nature 292:413-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmgren, J., C. Czerkinsky, N. Lycke, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1994. Strategies for the induction of immune responses at mucosal surfaces making use of cholera toxin B subunit as immunogen, carrier, and adjuvant. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 50:42-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, P. H., L. Eckmann, W. J. Lee, W. Han, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1998. Cholera toxin and cholera toxin B subunit induce IgA switching through the action of TGF-beta 1. J. Immunol. 160:1198-1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kremer, L., A. Baulard, J. Estaquier, J. Content, A. Capron, and C. Locht. 1995. Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 85A antigen promoter region. J. Bacteriol. 177:642-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremer, L., L. Dupre, G. Riveau, A. Capron, and C. Locht. 1998. Systemic and mucosal immune responses after intranasal administration of recombinant Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin expressing glutathione S-transferase from Schistosoma haematobium. Infect. Immun. 66:5669-5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremer, L., G. Riveau, A. Baulard, A. Capron, and C. Locht. 1996. Neutralizing antibody responses elicited in mice immunized with recombinant bacillus Calmette-Guerin producing the Schistosoma mansoni glutathione S-transferase. J. Immunol. 156:4309-4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langermann, S., S. Palaszynski, A. Sadziene, C. K. Stover, and S. Koenig. 1994. Systemic and mucosal immunity induced by BCG vector expressing outer-surface protein A of Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature 372:552-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liljeqvist, S., P. Samuelson, M. Hansson, T. N. Nguyen, H. Binz, and S. Stahl. 1997. Surface display of the cholera toxin B subunit on Staphylococcus xylosus and Staphylococcus carnosus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2481-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGhee, J. R., M. E. Lamm, and W. Strober. 1999. Mucosal immune responses: an overview, p. 485-506. In P. L. Ogra, J. Mestecky, M. E. Lamm, W. Strober, J. Bienenstock, and J. R. McGhee (ed.), Mucosal immunology, 2nd ed. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 17.McSorley, S. J., C. Rask, R. Pichot, V. Julia, C. Czerkinsky, and N. Glaichenhaus. 1998. Selective tolerization of Th1-like cells after nasal administration of a cholera toxoid-LACK conjugate. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:424-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mielcarek, N., S. Alonso, and C. Locht. 2001. Nasal vaccination using live bacterial vectors. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 51:55-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogra, P. L., H. Faden, and R. C. Welliver. 2001. Vaccination strategies for mucosal immune responses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:430-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohara, N., and T. Yamada. 2001. Recombinant BCG vaccines. Vaccine 19:4089-4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierre, P., O. Denis, H. Bazin, E. Mbongolo Mbella, and J. P. Vaerman. 1992. Modulation of oral tolerance to ovalbumin by cholera toxin and its B subunit. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:3179-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranes, M. G., J. Rauzier, M. Lagranderie, M. Gheorghiu, and B. Gicquel. 1990. Functional analysis of pAL5000, a plasmid from Mycobacterium fortuitum: construction of a “mini” mycobacterium-Escherichia coli shuttle vector. J. Bacteriol. 172:2793-2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Bustos, E., A. Sierra-Beltran, M. J. Romero, C. Rodriguez-Jaramillo, and F. Ascencio. 2000. Protection of BALB/c mice against experimental Helicobacter pylori infection by oral immunisation with H. pylori heparan sulphate-binding proteins coupled to cholera toxin beta-subunit. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:535-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sack, D. A., S. Huda, P. K. Neogi, R. R. Daniel, and W. M. Spira. 1980. Microtiter ganglioside enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for vibrio and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins and antitoxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11:35-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slos, P., P. Dutot, J. Reymund, P. Kleinpeter, D. Prozzi, M. P. Kieny, J. Delcour, A. Mercenier, and P. Hols. 1998. Production of cholera toxin B subunit in Lactobacillus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 169:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stok, W., P. J. van der Heijden, and A. T. Bianchi. 1994. Conversion of orally induced suppression of the mucosal immune response to ovalbumin into stimulation by conjugating ovalbumin to cholera toxin or its B subunit. Vaccine 12:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun, J. B., J. Holmgren, and C. Czerkinsky. 1994. Cholera toxin B subunit: an efficient transmucosal carrier-delivery system for induction of peripheral immunological tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:10795-10799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, J. B., N. Mielcarek, M. Lakew, J. M. Grzych, A. Capron, J. Holmgren, and C. Czerkinsky. 1999. Intranasal administration of a Schistosoma mansoni glutathione S-transferase-cholera toxoid conjugate vaccine evokes antiparasitic and antipathological immunity in mice. J. Immunol 163:1045-1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun, J. B., C. Rask, T. Olsson, J. Holmgren, and C. Czerkinsky. 1996. Treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by feeding myelin basic protein conjugated to cholera toxin B subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:7196-7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun, J. B., B. G. Xiao, M. Lindblad, B. L. Li, H. Link, C. Czerkinsky, and J. Holmgren. 2000. Oral administration of cholera toxin B subunit conjugated to myelin basic protein protects against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing transforming growth factor-beta-secreting cells and suppressing chemokine expression. Int. Immunol. 12:1449-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toossi, Z., P. Gogate, H. Shiratsuchi, T. Young, and J. J. Ellner. 1995. Enhanced production of TGF-beta by blood monocytes from patients with active tuberculosis and presence of TGF-beta in tuberculous granulomatous lung lesions. J. Immunol. 154:465-473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiner, H. L. 2001. The mucosal milieu creates tolerogenic dendritic cells and T(R)1 and T(H)3 regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2:671-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, H. Y., and M. W. Russell. 1993. Induction of mucosal immunity by intranasal application of a streptococcal surface protein antigen with the cholera toxin B subunit. Infect. Immun. 61:314-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, R. G., D. L. Scott, M. L. Westbrook, S. Nance, B. D. Spangler, G. G. Shipley, and E. M. Westbrook. 1995. The three-dimensional crystal structure of cholera toxin. J. Mol. Biol. 251:563-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]