Abstract

The secreted Mac protein made by serotype M1 group A Streptococcus (GAS) (designated Mac5005) inhibits opsonophagocytosis and killing of GAS by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. This protein also has cysteine endopeptidase activity against human immunoglobulin G (IgG). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to identify histidine and aspartic acid residues important for Mac IgG endopeptidase activity. Replacement of His262 with Ala abolished Mac5005 IgG endopeptidase activity. Asp284Ala and Asp286Ala mutant proteins had compromised enzymatic activity, whereas 21 other Asp-to-Ala mutant proteins cleaved human IgG at the apparent wild-type level. The results suggest that His262 is an active-site residue and that Asp284 and Asp286 are important for the enzymatic activity or structure of Mac protein. These Mac mutants provide new information about structure-activity relationships in this protein and will assist study of the mechanism of inhibition of opsonophagocytosis and killing of GAS by Mac.

The human pathogen group A Streptococcus (GAS) has evolved multiple mechanisms to evade host defenses, such as phagocytosis and killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) and complement-mediated cell lysis (2, 3). Recently, we identified a secreted protein (designated Mac) with homology to the α-subunit of human Mac-1 protein by proteome analysis of culture supernatant proteins made by serotype M1 and M3 GAS strains (5). Analysis of sera obtained from human patients with GAS infections and mice with soft tissue infections revealed that Mac is made in the course of host-pathogen interactions (5, 6). We reported that Mac binds to human PMNs, diminishes IgG binding to CD16, and inhibits opsonophagocytosis and killing of GAS by human PMNs (6).

Subsequently, it was found that Mac has proteinase activity against human IgG (10), although it does not have significant homology with other known proteases. DNA sequence analysis of the mac gene in natural populations of GAS identified two major allele families of mac that differ from one another largely due to substantial divergence in the middle one-third of the mac gene and Mac protein (Fig. 1) (7). We have also shown that two Mac variants (Mac5005 made by serotype M1 strain MGAS5005 and Mac8345 made by serotype M28 strain MGAS8345) representing two Mac variant complexes have IgG endopeptidase activity (7). Replacement of Cys94 with Ala destroyed the IgG endopeptidase activity of Mac5005 (7), consistent with the idea that this amino acid is a catalytically active residue, an idea put forth on the basis of biochemical data (10). A thiolate-imidazolium ion pair formed from the side chains of active-site residues Cys and His is used for catalysis in many cysteine proteases (8). In addition, an Asp residue is sometimes involved in enzymatic activity in cysteine proteases (1). The goal of the present study was to gain additional insight into structure-activity relationships in Mac protein by identifying histidine and aspartic acid residues involved in Mac IgG endopeptidase activity. We also sought to generate mutant proteins that would be useful for subsequent studies on the mechanism of inhibition of opsonophagocytosis and killing of GAS by Mac.

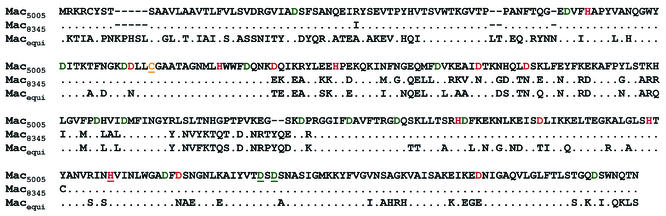

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of Mac5005, Mac8345, and a Mac homologue of S. equi (Macequi), highlighting the conserved Cys (C) (orange), His (H) (red), and Asp (D) (green) and nonconserved Asp (burgundy) amino acid residues. The Cys94, His262, Asp284, and Asp286 residues important for Mac5005 IgG endopeptidase activity are underlined. Amino acid residues identical to those in wild-type Mac5005 (.) and gaps introduced to maximize alignment (-) are indicated.

Amino acid sequence alignment found that 6 His and 16 Asp residues are conserved among protein Mac5005, Mac8345, and a Mac homologue of Streptococcus equi (Fig. 1). These conserved His and Asp residues of the Mac5005 protein were each replaced with alanine using a QuickChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), pSP22 containing mac5005 (5), and oligonucleotide primers (Table 1). The mutant genes were sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired nucleotide substitution and rule out spurious mutations. Each recombinant Mac mutant was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) containing a plasmid with the corresponding mac mutant gene. To screen for IgG endopeptidase activity, recombinant E. coli BL21 was grown at 37°C for 10 h in 3 ml of Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin per liter. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, suspended in 0.3 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), and sonicated for 10 s. The lysate was centrifuged to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was assayed for enzymatic activity.

TABLE 1.

Mac5005 amino acid replacements and primers

| Mac5005mutant | Primer (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| H70A | AAGGTGAAGATGTTTTTGCTGCTCCTTATGTTGCTAAC GTTAGCAACATAAGGAGCAGCAAAAACATCTTCACCTTC |

| H104A | CAGCAGGGAATATGCTTGCTTGGTGGTTCGATCAAAAC GTTTTGATCGAACCACCAAGCAAGCATATTCCCTGCTG |

| H121A | AACGTTATTTGGAAGAGGCTCCAGAAAAGCAAAAAATA TATTTTTTGCTTTTCTGGAGCCTCTTCCAAATAACGTT |

| H224A | GCTATTGACAAGTCGTGCAGATTTTAAAGAAAAAAATC GATTTTTTTCTTTAAAATCTGCACGACTTGTCAATAGC |

| H253A | GGCTCTAGGCCTATCAGCTACCTACGCTAACGTACGCGC GTACGTTAGCGTAGGTAGCTGATAGGCCTAGAGCC |

| H262A | CTAACGTACGCATCAACGCTGTTATAAACCTGTGGG CCCACAGGTTTATAACAGCGTTGATGCGTACGTTAG |

| D30A | GAAGGAGATATACATATGGCTAGTTTTTCTGCTAATC GATTAGCAGAAAAACTAGCCATATGTATATCTCCTTC |

| D67A | CTTCACTCAAGGTGAAGCTGTTTTTCACGCTCCTTATG CATAAGGAGCGTGAAAAACAGCTTCACCTTGAGTGAAG |

| D81A | GCTAACCAAGGATGGTATGCTATTACCAAAACATTCAAT ATTGAATGTTTTGGTAATAGCATACCATCCTTGGTTAGC |

| D90A | CAAAACATTCAATGGAAAAGCAGATCTTCTTTGCGGGGC GCCCCGCAAAGAAGATCTGCTTTTCCATTGAATGTTTTG |

| D91A | CATTCAATGGAAAAGACGCTCTTCTTTGCGGGGCTGC GCAGCCCCGCAAAGAAGAGCGTCTTTTCCATTGAATG |

| D108A | ATGCTTCACTGGTGGTTCGCTCAAAACAAAGACCAAATT AATTTGGTCTTTGTTTTGAGCGAACCACCAGTGAAGCAT |

| D112A | GGTTCGATCAAAACAAAGCTCAAATTAAACGTTATTTGG CCAAATAACGTTTAATTTGAGCTTTGTTTTGATCGAACC |

| D136A | GGCGAACAGATGTTTGCTGTAAAAGAAGCTATCGACACT AGTGTCGATAGCTTCTTTTACAGCAAACATCTGTTCGCC |

| D142A | GACGTAAAAGAAGCTATCGCTACTAAAAACCACCAGCTA TAGCTGGTGGTTTTTAGTAGCGATAGCTTCTTTTACGTC |

| D149A | CTAAAAACCACCAGCTAGCTAGTAAATTATTTGAATATT AATATTCAAATAATTTACTAGCTAGCTGGTGGTTTTTAG |

| D174A | CACCTAGGAGTTTTCCCTGCTCATGTAATTGATATGTTC GAACATATCAATTACATGAGCAGGGAAAACTCCTAGGTG |

| D178A | TTCCCTGATCATGTAATTGCTATGTTCATTAACGGCTAC GTAGCCGTTAATGAACATAGCAATTACATGATCAGGGAA |

| D202A | GTAAAAGAAGGTAGTAAAGCTCCCCGAGGTGGTATTTTT AAAAATACCACCTCGGGGAGCTTTACTACCTTCTTTTAC |

| D209A | CCCCGAGGTGGTATTTTTGCTCCGTATTTACAAGAGGT ACCTCTTGTAAATACGGAGCAAAAATACCACCTCGGGG |

| D216A | GCCGTATTTACAAGAGGTGCTCAAAGTAAGCTATTGACA TGTCAATAGCTTACTTTGAGCACCTCTTGTAAATACGGC |

| D226A | CTATTGACAAGTCGTCATGCTTTTAAAGAAAAAAATCTC GAGATTTTTTTCTTTAAAAGCATGACGACTTGTCAATAG |

| D237A | CTCAAAGAAATCAGTGCTCTCATTAAGAAAGAGTTAACC GGTTAACTCTTTCTTAATGAGAGCACTGATTTCTTTGAG |

| D270A | ATAAACCTGTGGGGAGCTGCTTTTGATTCTAACGGGAAC GTTCCCGTTAGAATCAAAAGCAGCTCCCCACAGGTTTAT |

| D272A | GTGGGGAGCTGACTTTGCTTCTAACGGGAACCTTAAAGC GCTTTAAGGTTCCCGTTAGAAGCAAAGTCAGCTCCCCAC |

| D284A | AAAGCTATTTATGTAACAGCTTCTGATAGTAATGCATCT AGATGCATTACTATCAGAAGCTGTTACATAAATAGCTTT |

| D286A | ATTTATGTAACAGACTCTGCTAGTAATGCATCTATTGGT ACCAATAGATGCATTACTAGCAGAGTCTGTTACATAAAT |

| D316A | CTAAAGAAATAAAAGAAGCTAATATTGGTGCTCAAGTAC GTACTTGAGCACCAATATTAGCTTCTTTTATTTCTTTAG |

| D333A | ACACTTTCAACAGGGCAAGCTAGTTGGAATCAGACCAAT ATTGGTCTGATTCCAACTAGCTTGCCCTGTTGAAAGTGT |

| D284A/ | CTTAAAGCTATTTATGTAACAGCTTCTGCTAGTAATGCATCTATTGG |

| D286A | CCAATAGATGCATTACTAGCAGAAGCTGTTACATAAATAGCTTTAAG |

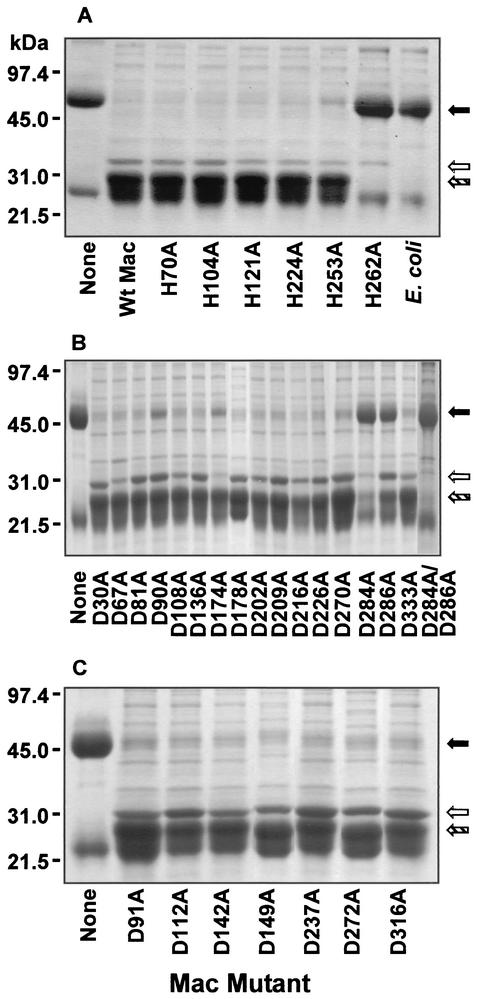

The control E. coli lysate did not cleave human IgG heavy chain (Fig. 2A). The Mac5005 His262Ala mutant did not cleave IgG, whereas the other five Mac5005 His-to-Ala mutant proteins had apparent wild-type proteolytic activity (Fig. 2A), consistent with the idea that His262 is critical for IgG endopeptidase activity. Also consistent with this notion, replacement of the corresponding His residue of Mac8345 (His264) with Ala resulted in a mutant protein that did not cleave IgG (data not shown). These results suggest that His262 of Mac5005 and His264 of Mac8345 play a catalytic role in the enzymatic activity.

FIG. 2.

IgG endopeptidase activity of Mac mutants assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis. IgG was treated with Mac mutants present in recombinant E. coli lysates (H, histidine; D, aspartic acid; A, alanine). (A) Digestion of IgG heavy chain by histidine-to-alanine Mac mutants. Treatment of IgG with E. coli lysate alone or wild-type (Wt) Mac5005 was included as controls. (B) Digestion of IgG heavy chain by conserved aspartic acid-to-alanine Mac5005 mutants. The rightmost lane contains an Asp284Ala and Asp286Ala double mutant (D284A/D286A). (C) Digestion of IgG heavy chain by nonconserved aspartic acid-to-alanine Mac5005 mutants. The positions of undigested human IgG heavy chain (black arrow), recombinant Mac protein (white arrow), and proteolytic product (hatched arrow) are shown to the right of the gels.

Replacement of 14 of the 16 conserved Asp residues in Mac5005 protein with Ala did not demonstrably alter IgG endopeptidase activity (Fig. 2B). However, the Asp284Ala and Asp286Ala amino acid replacements resulted in substantially decreased enzymatic activity (Fig. 2B). The level of enzymatic activity of the Asp284Ala/Asp286Ala double-mutant protein was similar to that of the Asp284Ala mutant protein (Fig. 2B), ruling out the possibility that Asp284 of Asp286Ala mutant protein and Asp286 of Asp284Ala mutant protein were responsible for the residual activities of the mutants. Inasmuch as Mac5005 and Mac8345 have more than 50% mismatched amino acid residues in the central one-third of the proteins, it is possible that nonconserved Asp residues may be important for enzymatic activity. To rule out this possibility, seven nonconserved Asp residues of Mac5005 were replaced with Ala. All of these mutants cleaved human IgG at the apparent wild-type level (Fig. 2C).

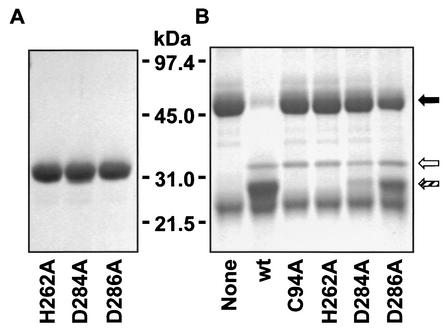

To compare enzymatic activity more accurately, the Mac5005 His262Ala, Asp284Ala, and Asp286Ala mutant proteins were purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 3A) by the procedures previously described for the wild-type Mac5005 protein (7). All of the results generated with crude recombinant enzyme present in the E. coli lysates were confirmed with the purified mutant proteins (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

(A) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of purified recombinant His262Ala, Asp284Ala, and Asp286Ala Mac5005 mutant proteins. (B) Digestion of human IgG heavy chain by the purified Mac5005 mutant proteins. Wild-type (wt) Mac5005 and Cys94Ala Mac5005 mutant proteins were included for comparison. The positions of undigested human IgG heavy chain (black arrow), recombinant Mac protein (white arrow), and proteolytic product (hatched arrow) are shown to the right of the gel.

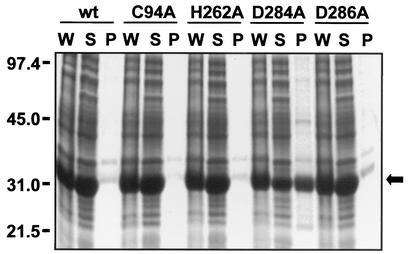

The Mac5005 Asp284Ala mutant protein was present in the E. coli lysate at a level notably lower than those of the wild-type and most of the other mutant proteins (Fig. 2B), suggesting that this mutant protein might form an insoluble aggregate (inclusion body). To examine this issue further, the levels of the Asp284Ala mutant protein present in the whole cell, soluble fraction, and insoluble fraction of the recombinant E. coli cells were compared with those of wild-type and Cys94Ala, His262Ala, and Asp286Ala mutant Mac5005 proteins. The amount of Mac5005 Asp284Ala mutant protein present as an inclusion body exceeded those of the other recombinant Mac proteins (Fig. 4), suggesting that the Asp284Ala amino acid replacement changes the structure of Mac. In contrast, the Asp286Ala mutant protein did not form an inclusion body (Fig. 4), suggesting that this amino acid replacement did not alter the structure of Mac. Although the decrease in the enzymatic activity caused by the Asp286Ala mutation suggests that Asp286 participates in catalysis, an alternative explanation is that this aspartic acid residue simply enhances proteolytic efficiency. Consistent with this idea, only cysteine and histidine amino acid residues are used for catalysis in many cysteine proteases, with other amino acids serving to increase enzyme efficiency by stabilizing the active-site conformation (9).

FIG. 4.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of the whole cell (W), soluble fraction (supernatant [S]), and insoluble fraction (pellet) of the recombinant E. coli cells demonstrating that more than 50% of Mac5005 Asp284Ala mutant protein was present in an inclusion body. Wild-type (wt) and Cys94Ala, His262Ala, and Asp286Ala mutant Mac5005 proteins not forming an inclusion body were included for comparison. The position of Mac protein is indicated by the arrow to the right of the gel.

In summary, we identified amino acid residues important for Mac IgG endopeptidase activity, thereby providing new insight into structure-activity relationships in this important virulence protein. Together with our previous site-specific mutagenesis results for Cys94 (7), the data suggest that Cys94 and His262 are active-site residues, and Asp284 and Asp286 are important for the enzymatic activity or structure of Mac. As shown for streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B, another extracellular cysteine protease made by GAS (4), crystal structure analysis will be important to resolve the relationships of the amino acid residues in and around the active site and to define the catalytic and structural roles of these residues. The Mac mutants described herein will facilitate further study of the mechanism used by Mac to inhibit opsonophagocytosis and killing of GAS by human PMN (6, 7).

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett, A. J., and N. D. Rawlings. 2001. Evolutionary lines of cysteine peptidase. Biol. Chem. 382:727-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank, M. M. 2001. Annihilating host defense. Nat. Med. 7:1285-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kagawa, T. F., J. C. Cooney, H. M. Baker, S. McSweeney, M. Liu, S. Gubba, J. M. Musser, and E. N. Baker. 2000. Crystal structure of the zymogen form of the streptococcal virulence factor SpeB: an integrin-binding cysteine protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2235-2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lei, B., F. R. DeLeo, N. P. Hoe, M. R. Graham, S. M. Mackie, R. L. Cole, M. Liu, H. R. Hill, D. E. Low, M. J. Federle, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evasion of human innate and acquired immunity by a bacterial homologue of CD11b that inhibits opsonophagocytosis. Nat. Med. 7:1298-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lei, B., F. R. DeLeo, S. D. Reid, J. M. Voyich, L. Magoun, M. Liu, K. R. Braughton, S. Ricklefs, N. P. Hoe, R. L. Cole, J. M. Leong, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Opsonophagocytosis-inhibiting Mac protein of group A Streptococcus: identification and characteristics of two genetic complexes. Infect. Immun. 70:6880-6890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis, S. D., F. A. Johnson, and J. A. Shafer. 1981. Effect of cysteine-25 on the ionization of histidine-159 in papain as determined by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy: evidence for a His-159-Cys-25 ion pair and its possible role in catalysis. Biochemistry 20:48-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernet, T., D. C. Tessier, J. Chatellier, C. Plouffe, T. S. Lee, D. Y. Thomas, A. C. Storer, and R. Menard. 1995. Structural and functional roles of asparagine 175 in the cysteine protease papain. J. Biol. Chem. 270:16645-16652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Pawel-Rammingen, U., B. P. Johansson, and L. Björck. 2002. IdeS, a novel streptococcal cysteine proteinase with unique specificity for immunoglobulin G. EMBO J. 21:1607-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]