Abstract

Health care for the Kenyan pastoralist people has serious shortcomings and it must be delivered under difficult circumstances. Often, the most basic requirements cannot be met, due to the limited accessibility of health care provisions to pastoralists. This adds major problems to the daily struggle for life, caused by bad climatic circumstances, illiteracy and poverty.

We argue that strong, integrated and community based primary health care could provide an alternative for these inadequacies in the health system. The question then is how primary health care, which integrates a diversity of basic care provisions, such as pharmaceutical provision, child delivery assistance, mother and childcare and prevention activities, can be implemented. In our view, an appropriate mix of decentralisation forms, warranting better conditions on the one hand and relying on the current community and power structures and culture on the other hand, would be the best solution for the time being.

Keywords: Africa, pastoralists, decentralisation, community care, integration of services

Introduction

The problem of pastoralism in Kenya and elsewhere today is that of its very survival. Pastoralists face dwindling resources, uncertainties and poor health—related to malnutrition, the pastoralist life style, the AIDS/HIV pandemic and the current economic difficulties in the country. Living in areas characterised by low population densities and extensive geographical dispersion with long distances between service delivery points, pastoralists have not profited from service delivery programmes. This happens while the Kenyan health system in general shows significant shortcomings, such as a lack of qualified and motivated staff.

Even long before the current economic problems in Kenya, delivery of health care among the pastoral population showed major deficiencies. In particular, access to services is limited, and minor ailments continue to cause morbidity and mortality. Although immunisation coverage in parts of Kenya, which are inhabited by pastoralist, has probably improved, it still lags behind as compared to the rest of the country. Attempts have been made to increase the number of health care delivery points. However, these do not target pastoral people, but their sedentary counterparts only. Efforts to establish mobile outreach services have failed, due to the high running and maintenance cost.

In our view, to improve this situation, the development of strong, integrated and community based primary health care, which is strongly advocated for in the global call of Health for All (1977), is helpful to give access to basic health care for pastoralist people. In this article, we discuss how primary health care can be developed for the pastoralists in Kenya. We will demonstrate that a firmly established decentralised district management is a basic requisite for success. We will focus on the Marsabit district of Northern Kenya where over 80% of the population are pastoralists. In addition, references are made to other districts in Kenya (for a map of districts, please click http://kenyaweb.com/regions/).

We start with an outline of the health system of Kenya. This is followed by a description of the situation in Marsabit district, including the accessibility for pastoralists of formal and informal services. After that, we turn to our main topic: the relevance of primary health care for pastoralists, and strategies for implementing primary health care. Finally, we draw a number of conclusions. In addition to research data, this paper is based on observations by the first author.

The health system of Kenya

In 1999, Kenya had a population of 29,549,000 inhabitants. For females and males, in 1999, life expectancy at birth was 48.1 and 47.3 years, respectively (http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm). Here, we briefly outline some characteristics of the Kenyan health system. They concern institutions and financing, and the policy of the Ministry of Health.

Health services institutions and financing

For 1997, the total health expenditure in Kenya was estimated to be 4.6% of the GDP. 64.1% of the total health expenditure concerned public expenditure, while 35.9% concerned private, out-of-pocket expenditure. Public expenditure on health was estimated at 11.2% of all public expenditure (http://www3.who.int/whosis/menu.cfm). For the larger part, health services in Kenya are delivered by government and church organisations [16]. In addition, there is a wide range of private and nongovernmental hospitals and health centres. Traditional healers are an important part of the health system in both rural and urban areas. Although there is a strong private medical care sector, the bulk of the population relies heavily on the public health sector [14].

Services in the private sector are provided at a fee. Before 1989, preventive and curative services in government health facilities were provided free of charge to the public. In some cases, the fee for preventive services in missionary health facilities has been subsidised by the government. Since 1989, people have to pay for curative services [5, 9]. Service provision in government dispensaries has remained free of charge. It is expected that in the near future user charges will be increased in government hospitals and health centres, in view of the external pressure for market-based reforms. In addition, probably fees will be introduced in government dispensaries [14].

Development and organisation of the health system

Immediately upon gaining independence in 1963, the Kenyan government announced measures to reduce poverty, ignorance and disease, which were considered major hindrances to national development. The Ministry of Health was charged with the responsibility of organising, overseeing and directing health service delivery all over the country. The Ministry launched an all encompassing, nationwide plan for building an infrastructure of hospitals, health centres and dispensaries. Today there are 3200 health care institutions nationwide. Half of these are maintained and run by the Ministry of Health. The remaining half were built and maintained by non-governmental organisations, missionaries and the private sector. The health services institutions cover preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative care. According to the government's policy, each district was supposed to have at least one hospital that also would serve as a referral point for the outlying health centres and dispensaries [10]. To deliver better health care in the government run facilities, the Ministry trained health personnel of various categories, e.g. doctors, nurses, paramedical personnel, dentists, community health workers, environmental health officers. This was done at the universities and intermediate colleges, most of which were directly under its control. In addition, some of the non-governmental sectors, especially the religious based organisations, were allowed to train their nurses and other paramedical staff.

Typical of the health system in Kenya was central decision-making. Health service administration was characterised by a top-down, centre driven process of control. Plans were developed at the Ministry headquarters, while provinces and districts were instructed to implement them on behalf of the Ministry. Drugs and medical supplies were also processed through the Ministry and handed over to the periphery for consumption. Budgets were introduced and funds were allocated to the districts without further consultation. The provincial health team as the basic administrative level and the district health management teams, operating from the district hospitals served both as providers and as the Ministry's administrative representatives. The district health team was held accountable to the provincial management teams and, in turn, the province to the Ministry headquarters. The dispensary and health centre staff were answerable to the district health team accordingly.

In recent years, efforts have been made to change this situation. The health sector reform programme was launched in 1994, which advocates decentralisation of services. As a result, the districts are being revitalised as the overall centre for decision-making. To further promote this development, the district health management teams are being strengthened through training, and district health boards are being installed as the main stakeholders to represent the community's interest [10]. The district health teams are now authorized to raise some revenues through user free charge and to plan service delivery programmes for the district in collaboration with the district health management board. As a result, the district teams must now deal with many challenges, some of which will be discussed below.

In Kenya in general (including Marsabit district), there are two forms of health care: first, the formal officially sanctioned hospital/institution based health care according to western scientific medicine and, second, the informal community oriented culturally/traditionally supported indigenous system. Generally, ill people move between both the formal and informal sectors, sometimes using them both and sometimes adhering to one only, when the treatment in the other sector fails to relieve physical discomfort or emotional distress. The actors in the formal sector are professionals who include physicians, nurses, midwives and paramedics [7]. They operate as public health care providers under the auspices of the Ministry of Health, or as private and non-governmental workers. The informal sector is composed of the traditional health care providers and over-the-counter suppliers of medicines. The traditional herbalists and birth attendants are among the most popular members of this latter group. Although they have continued to provide services in the communities long before the introduction of western medicine in most areas of Kenya, they have been denied legal status as defined by the laws of the country. This has isolated them and distrust and suspicion mark their relationship with the formal sector. However, the reality is that, whether supported or not by the formal sector, the traditional health practitioners in rural Kenya still occupy today a very prestigious place in society. They share the basic cultural values of the society they live in and they hold similar views about the origin, significance and treatment of ill health to which the population ascribes [7].

The situation in Marsabit District

In this section, we discuss the geographical and other features of Marsabit district, and the accessibility of formal and informal health services.

Features of Marsabit district and its pastoralists' health

Marsabit district is one of thirteen districts in Kenya, which are predominantly occupied by pastoralists. With an area of 78,078 square kilometres, it is one of the largest in the country, covering about 13–14% of the total area of Kenya. Administratively, the district is divided into six divisions, which are further subdivided into locations and sub locations.

Marsabit has a population of about 150,000 people, giving a population density of about two persons per square kilometre. Pastoralism is the main preoccupation of 84% of the people. This means that they derive most of their subsistence from keeping domestic livestock in condition, where most of the feed that their livestock eat is natural forage rather than cultivated fodder and pastures (Baxter, 1992). There are three groups of pastoralists. First, there are the pastoral nomads, who rear livestock for their own use and for barter. They do not practice any agriculture or have any permanent places of abode, but they migrate in a seasonal manner. Second, there are semi-nomads who are engaged in unspecialised herding and farming which is mainly a mixed form of subsistence. The third form of pastoralism is practised by sedentary people whose main economic activity is farming. Their seasonal movements are limited in scale, involving only cowherds, shepherds or goatherds (Omar, 1994).

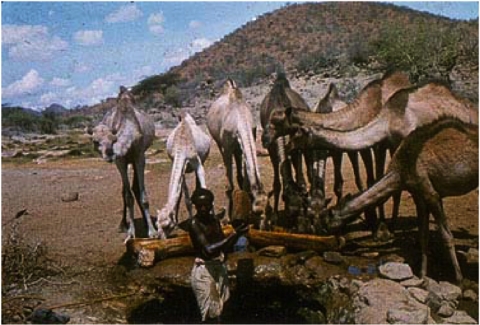

Climatically, Marsabit is one of the driest districts in Kenya. The mean annual rainfall ranges between 150 mm in the low-lying areas to 800 mm in the highlands [11, 12]. Rainfall is erratic and unreliable. The low rainfall is one of the principal factors explaining why pastoralists occupy the district. An annual rainfall of 150 mm is not sufficient for agriculture, and therefore the search for water and pasture is the main reason for the pastoralists' mobility. In essence, the animals migrate and the owners follow them (Omar, 1994). Due to this regular movement, it has always been very difficult to provide the pastoralists with the appropriate health (and others such as veterinary or educational) services, as these services are delivered by stationary facilities. As a result, the pastoralists have difficulties getting treatment for health problems.

Another complicating factor here is the relationship with the livestock they keep. The pastoralists' survival is inextricably intertwined with the existence of their stock. Most pastoralists consider their livestock not only a property but also a means of survival. The animals have a special role in their socio-cultural pattern, which regulates the society's existence. They are used as dowry during marriage, sacrificed during bereavement and offered during prayers. Due to these tight man–animal relations, it is difficult to separate out the special health care for people as one that is completely different from that of the livestock. This situation manifests itself clearly when we look at the factors which affect the pattern of diseases among pastoralists. Although the main cause of morbidity and mortality among pastoralists in Marsabit district are malaria, diarrhoea, respiratory tract infection, measles and tuberculosis, there are also particular disease problems resulting from their animal keeping life (Swift, 1988). For example, because of their proximity to animals, they suffer from diseases such as anthrax and brucellosis. Another consequence of their keeping livestock is that their diet is limited with milk and meat as a main ingredient. The nutritional value of this diet is mainly protein, causing problems of malnutrition.

Access to formal health services for pastoralists in Marsabit District

The number of formal service provisions over the Marsabit divisions is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of health facilities by type and providers in Marsabit District

| Division | Hospitals | Health centers | Dispensaries | Private clinics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 1 | – | 4 | 5 |

| North-Horr | – | 3 | 2 | – |

| Maikona | – | – | 4 | – |

| Loiyangalani | – | 2 | 1 | – |

| Moyale | 1 | – | 3 | 7 |

| Sololo | 1 | – | 3 | – |

| Laisamis | 1 | – | 4 | – |

| Total | 4 | 5 | 21 | 12 |

Source: Ministry of Planning and National Development (1997).

It should be noted that all four hospitals are found along the main highway and in areas that are more central, where transportation and access are relatively easy. It is also noteworthy that the private providers are all concentrating their services in Central Division and Moyale, which are more accessible and convenient than the other remote divisions. In addition, the functioning of the hospitals and other health care provisions is problematic. Although the hospital is supposed to serve as a referral point for the smaller facilities, i.e. the dispensaries and health centres, this function is almost non-existent. In most instances, the hospital is often not different from those smaller units it is supposed to support. The number of personnel may be sufficient in terms of quantity, but not in terms of quality. Personnel often lack the appropriate skills and motivation. This is mainly caused by the high turnover of those with the proper skills, who prefer to transfer from the district or who resign to join institutions where they are well paid. Lack of incentives and poor pay, poor management and lack of resources are some of the major factors contributing to these problems in the hospitals. As a result, for example, often there is only one physician, who is expected to attend to emergencies, work in the theatre, see special cases and handle administrative duties. The same goes for dispensaries and health centres: it is not unusual to see them remain closed, due to a lack of personnel or drugs and supplies that are essential for daily operations. This especially goes for North-Horr, Loiyangalani, Maikona and Laisamis, where the majority of the people are pastoralists.

Another problem is the distance that the patients in various divisions have to travel to reach the health facilities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Average distance to health facility by division in Marsabit District

| Division | Average distance in km |

|---|---|

| Central | 9 |

| North-Horr | 80 |

| Loiyangalani | 80 |

| Moyale | 50 |

| Sololo | 16 |

| Laisamis | 60 |

Source: Ministry of Planning and National Development (1994b).

In Marsabit district, the average distance to the nearest health facility is 60 km. The mainly pastoralist divisions of North-Horr, Loiyangalani and Laisamis have the longest distances to health care facilities. Here, the problem of distance is complicated by a lack of transportation. People resort to walking, camels, donkeys or even humans to transfer the critically ill to the health facilities. Considering the long distance to these facilities, death can sometimes intervene before they are reached. Especially for the critically ill, children, elderly and expectant women the long distance to service delivery points is a burden.

North Horr, Loiyangalani and Laisamis also show the lowest medical/population ratio (Table 3) and the lowest bed/patient ratio (Table 4).

Table 3.

Medical-personnel population ratio by division in Marsabit District

| Division | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Central | 1:124 |

| North-Horr | 1:1993 |

| Maikona | 1:1090 |

| Loiyangalani | 1:1367 |

| Moyale | 1:246 |

| Sololo | 1:848 |

| Laisamis | 1:1240 |

Source: Ministry of Planning and National Development (1997).

Table 4.

Bed Patient ratio by division in Marsabit district

| Division | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Central | 1:124 |

| North-Horr | 1:2623 |

| Loiyangalani | 1:893 |

| Moyale | 1:379 |

| Sololo | 1:236 |

| Laisamis | 1:496 |

Source: Ministry of Planning and National Development (1994b).

Pastoralists are poor people. This is another reason why accessibility of the health services is limited. Because their financial means are scarce, they must weigh expenditure on health services against expenditure on other priorities such as food and clothing. This is not to say that pastoralists never are able to meet the costs of basic health care. However, they do not always have ready cash available to purchase services when they are needed. They may need to sell livestock and the decision to do this takes time, since decision-making may require involving the other members of the family. When the final decision is made, the livestock may need to be driven to the main market, which is often far away, while at the market the prices offered may not be favourable. There is then the issue of regular drought, which affects the livestock market as well. At this time, the animals grow thin and their market values subsequently diminish. This affects the family's income and thereby their purchasing power, not only for health needs but for other basic requirements as well.

Finally, the hospital environment is also not very conducive to pastoralists. They dislike some medicines or chemicals, due to their smell and bitter taste. In addition, the attitude and behaviour of health workers play a part: health workers show a tendency to pay little attention to unsophisticated and simple looking, poor pastoralists, who always seem ignorant and strange. They are thus forced to shy away and eventually withdraw. This makes the pastoralists reluctant to seek health care in hospitals and dispensaries, unless their health condition worsens.

In view of all these problems of getting access to formal health services, it would come as no surprise if people seek alternative, e.g. traditional care. Indeed, a substantial part of the rural population of Marsabit district ascribes to informal services.

Access to informal health services for pastoralists in Marsabit District

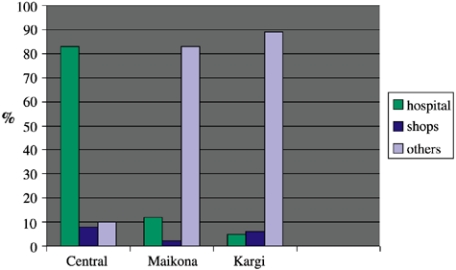

The services provided in the informal sector are mainly curative, and sometimes preventive and rehabilitative. It is given by herbalists, traditional birth attendants, bonesetters, seers and shops. Although the shops' role is not directly recognized, many healing activities take place here. Patients turn up and can easily purchase a medicine for an ailment such as pain, malaria and the common cold. Figure 1 demonstrates the use (in 1992) of hospitals and informal care (shops and others) in three Marsabit divisions: Central (with many formal facilities), Maikona and Kargi. There is a striking contrast between Central Division, with 83% of the people using hospital services when ill, and Maikona and Kargi divisions with 85% and 89% of the population, respectively, resorting to ‘others’.

Figure 1.

Use of services of hospitals, shops and others in three divisions of Marsabit District by percentage of users (Source: [3]).

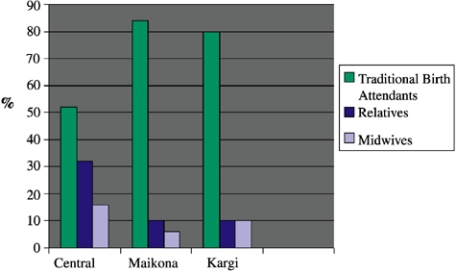

The traditional herbalists and midwives are easily accessible. They are among the most popular in the group of traditional health care providers. The highest percentage of deliveries in Marsabit district still takes place in the villages at the hands of the traditional birth attendants (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Use of services of traditional birth attendants, relatives or midwifes in three divisions of Marsabit District by percentage of users (Source: [3]).

Figure 2 also indicates that the communities remote from the urban centre show more adherence to traditional forms of treatment. It is important to note, however, that even in Central Division, where the district hospital is closer, trained midwives conducted only 15% of the deliveries. The rest sought the services of the traditional birth attendants or relatives/neighbours, following the cultural tradition in the country. Traditionally, delivery is the specialty of women and not men, who are commonly found conducting deliveries in most of the hospitals. The pastoralists' bonesetters are another authority to reckon with. Patients with fractures and dislocations rarely attend the hospitals, since the bonesetters treat this condition with a good degree of success, unlike the hospital where cases of disabilities have been experienced.

Primary health care to pastoralist people

Reasoning from the goal of Health for All, the foregoing description of the Kenyan system and the pastoralists' life circumstances indicate that the current health system for these people has considerable shortcomings. The health system is in need of change and innovation, to make services more readily accessible to pastoralists. Below we will discuss which innovations may be appropriate here and how these innovations should be implemented. We will argue that the primary health care approach is a plausible option here, although it is not to say that it provides a complete solution to all pastoralists' health problems.

The relevance of primary health care

According to the World Health Organisation's definition (1997), primary health care is…“essential health care based on practical scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology, made universally accessible to individuals and families in the communities, through their full participation and at a cost that the community and the country can afford (…) It is the first level of contact of individuals, the family and the community with the national health system, bringing health care as close as possible where people live and work, and constitutes the first element of a continuing health care process”.

An important element of the strategy advocated by the WHO, is that primary health care is most likely to be effective if understood and accepted by the community and applied at the cost the community and the country can afford. There is therefore the call for involving community leadership, health workers, including the traditional ones, in its development. It is stressed that the community health workers should reside in the community. They ought to be trained both socially and technically to respond to the expressed needs of the communities they serve. As indicated earlier, all this is lacking in the current health provision to the pastoralists in the Marsabit district. Here the health care resources are concentrated in centralised institutions, particularly hospitals, at the expense of access to health care given at the local levels in the community [2, 6]. The system is not integrated into the community. There is virtually no communication between the people and the system meant to serve them. This has further alienated and isolated the pastoralists, who already feel that they are not considered part of the government system. As a result, people continue to suffer and die from communicable diseases, which perhaps could be prevented by efficient planning, appropriate policy and fair distribution of resources.

The aim of the WHO primary health care strategy was achievement of health for all, by focussing on (sub) strategies concerning four main principle areas, i.e. universal accessibility to need (equity), community participation, intersectoral action and appropriate technology [18]. Application and relevance of each of the (sub) strategies in the frame of developing and delivering primary health care for the Kenyan pastoralists will be discussed below.

Relevant strategies in the frame of primary health care

Universal accessibility and coverage according to need: equity

Provision of adequate coverage of the most important health needs of a whole population (equity) not only means securing additional resources where possible, but also re-allocation of existing resources to those whose needs are greatest. This strategy clearly speaks out in the pastoralists' favour. Such equity can be achieved quicker by primary health care for pastoralists than in hospitals that, once built, cannot be moved. For example, in areas where distance and lack of transportation prevent people from reaching health facilities, trained primary health care workers should be brought into action for providing services at the first level of contact with the population. For this to happen in Marsabit several actions can be undertaken. For example, community health workers and traditional birth attendants could be trained and equipped with basic tools to work together in safe and hygienic circumstances (see also below). To improve access to basic drugs, a village pharmacy could be set up and administered by community health workers, for instance through a revolving community fund that ensures sustainability. In dispensaries and health centres, which are referral points for the community health workers and the traditional birth attendants, adequate staff with a pastoral background could be employed and basic supplies provided.

Community participation

Community participation is the process by which individuals and families assume responsibility for their own health and welfare and of those in the community. It is an important strategy to carry out primary health care for scattered isolated groups as pastoralists, because of the following reasons [4]:

It focuses on communities in their own setting, at the home and village level rather than at hospitals where the interest is on individual patients in a clinical setting.

It advocates primary prevention through appropriate measures before illness occurs rather than treating or curing illness afterwards.

Active community participation is encouraged in preventive efforts rather than patients' compliance with medical regimes.

Appropriate integration and application of social, behavioural, environmental and bio-medical sciences in designing strategies is the focus of intervention.

Community participation should include planning as well as the management of services. Involving people not only is a way of getting things done, but it also increases understanding, maintains interest and develops self-reliance. Furthermore, it lessens resistance to change [8]. Practically, one could think of appointing a member of the committee of community leaders to work with primary health care teams. As for pastoralist communities, traditional leadership is an important avenue, because traditional leaders are usually the ones responsible for dealing with community affairs. They are able to mobilise and build community support. An additional advantage is that they are regularly in contact with and deliberate about community issues, so that communication and decision-making on health affairs can easily be carried out. Another possibility to foster community participation is promoting and improving the role of traditional health practitioners in the delivery of community based primary health care in the villages and communities where they live.

Intersectoral action for health

It is recognised that the health of a society is closely related to its socio-economic situation and the extent of poverty within it. With this in mind, primary health care should not be the only responsible sector for health. Other sectors, which are important for national and community development, must bear responsibility as well, with special attention to agriculture, industry, education, animal husbandry, food, housing and public works. This requires the coordinated efforts of all those sectors [18], in order to achieve integrated care. The practical implication of this statement is that the health care system should be able to coordinate its actions with other sectors at the appropriate level. For example, a dispensary responsible for a defined pastoral population would need to work closely with the veterinary department, for instance by establishing a link to identify and promptly report outbreak of diseases in livestock and people. Subsequently, they should be able to jointly plan and carry out the control of such epidemics by sharing resources such as knowledge, personnel and transportation. They may also conduct human and livestock immunisation campaigns as well as education on human and livestock health. The close relation between pastoralists and their livestock would then be used as a channel for action and for communicating health information, for livestock and people.

Appropriate technology

Technology in primary health care refers to equipment as well as knowledge, organisational procedures and skills, to be combined for the sake of producing benefits [18]. The use of technology should contribute to cost-effectiveness, which means the allocation of technological resources in such a manner as to yield the greatest benefit, to be measured by the extent to which the health needs of the largest number of people can be met. For example, district health management teams could bring the services to the dispersed and ‘hard to reach’ population by investing more resources in simple dispensaries that are run by nurses along with public health technicians who provide preventive and promotive services. The dispensaries should then be equipped with the basic supplies and drugs to enable them to handle the health problems presented by the patients. The nurses and public health technicians could also be given more training in primary health care techniques, so that they are able to train the community health workers and traditional birth attendants. The best choice of community health workers for pastoral communities is the traditional health practitioners, who are already offering health care at this level. Once they are given a basic training as that required for conventional community health workers, and once they are formally recognised as ‘community doctors’, they could be more productive and deliver a better quality of care. Their training should focus on areas such as maternal and child health services, antenatal care, AIDS prevention and education on preventive and promotive care such as diarrhoeal disease control, as well as that of the zoonoses such as brucellosis and anthrax. The reason for this advocacy is that traditional health practitioners are reliable people who are already working in the community, offering the same services. They are recognised and accepted by the community and there is less chance of them abandoning the service, since they do not fully depend on it as a means of living. In addition, most of them perform a dual role in both human and animal health care. They could therefore be used for both purposes as long as they are willing to be trained. Experience so far shows that the traditional birth attendants are willing to be trained and the other groups (herbalists, bonesetters) are likely to support such an initiative. These personnel can serve as a link between the health system and the community in which they work. This link is also a point where to establish an intersectoral team of all stakeholders such as livestock and veterinary technicians who have close working interest with the community.

Summarizing the above strategies, it should be said that, to minimise cost and to maximise benefits to individuals and communities, the resources of community leadership and traditional health practitioners should be involved, thus making use of the prevailing power structures, routines and community structures. The same goes for better and more coordination between and within different sectors. A coherent primary health care development and delivery provides the best setting to practically realise these strategies.

Decentralisation for efficient implementation and management

Three types of decentralisation and its application in Kenya

As argued earlier, the development of primary health care should be undertaken at the most basic, community level of society. As, here:

one can find the most appropriate knowledge on culture, needs and daily life of the people the care is developed for and delivered to;

the support of the community can be promoted and be used as a basis for implementing the desired primary health care services;

communication and decision-making networks can more easily be established.

Another advantage of the adoption of such a decentralised manner of working is that it fits the current developments in Kenya quite well.

For some time now, the district level management has been the central player for the management of health services. To a certain degree, the central government transferred authority in public planning, management and decision making from the national level to the district level. It did so by three types of decentralisation, namely delegation, devolution and deconcentration as differentiated by the WHO (1997). Delegation pertains to the transfer of managerial responsibility for defined functions to organisations that are not covered and only indirectly controlled by the government structure. Devolution means creation or strengthening of sub national levels of government that are substantially independent of the national level with respect to a defined set of functions, such as local authorities. Deconcentration refers to handing over some administrative authority to locally based offices of central government Ministries. Depending on the type of decentralisation, the powers handed over may concern policy-making, legislative competences, revenue raising, resource allocation, deployment of staff, regulation, management, intersectoral collaboration and training [18].

All three forms of decentralisation to the district level can be considered a move towards the creation of community participation, motivation of local staff and transfer of decision-making nearer to the services. For handing over authority, deconcentration, however, is not as far-reaching a variant as the other two. It is exactly this form of decentralisation, which is most frequently applied by the national government. As a result, government control is still felt at the district level. There is still significant room left for steering from above by the Ministry, as far as approval of plans and policies are concerned. For example, alternative ways of raising revenues or seeking support from external sources without passing through the Ministry of Health (devolution) is not possible and yet some funders do not sponsor because of the bureaucratic procedure involved. The Ministry also has a say in the appointment of members of the district health management boards, who are the community representatives at the district level. It is doubtful if this agrees with the concepts of empowerment and self-reliance envisaged by the primary health care strategy.

On the other hand, it is important to maintain a certain degree of central control and influence by the Ministry, since implementation of national policies needs to be coordinated. In addition, the Ministry must be allowed to execute a certain amount of control over the districts. This way, it can prevent abuse of power by cliques or elites in the districts, although, currently there is no machinery to monitor possible abuse. Furthermore, decentralisation may enhance existing differences between districts, which is not considered acceptable. In addition, coordination of nation-wide implementation of primary health care is necessary to strike a balance with other developments in the health system. Finally, fragmentation of coordination may cause growing differences of opinions as to what the concept of primary health care should concern. This may later create new problems, including inequity.

Looking for the most appropriate mix of decentralisation

Because of the emphasis on deconcentration in Kenya, currently, the three types of decentralisation are not balanced. Thus, what should be worked on in the future is to achieve the most appropriate mix of types of decentralisation. It concerns a mix that fits the circumstances that are outlined below.

At short notice, for the pastoralist districts, the existing mix may very well be favourable. The main reason for this concerns financial resources. Most pastoralist districts are sparsely populated and very poor. They are not able to raise sufficient funds for running and maintaining services. They cannot afford employment and payment of staff and supply of drugs and equipment. This prompts them to regularly rely on the central government for financial support. In the case of deconcentration there is still room left for government support, because then services remain under control of the government. Total separation of the districts from the centre due to e.g. devolution, may not work out well under these circumstances. In addition, a slow and steady introduction of delegation is needed for the time being. In the case of delegation, the system is expected to raise and generate funds through the services it offers. This makes the system more expensive to the poor, which is incompatible with the primary health care principle of affordability and accessibility, when it results in exclusion of the poorer section of the community.

Notwithstanding that, in the long term, to create primary health care provision that better meets the pastoralists' needs, deconcentration should gradually become better balanced with the other types of decentralisation. A first step would be to give the districts more power to raise funds from donors and other interested supporters, without the obligation to pass through the bureaucratic procedures of the Ministry. More importantly, the government should secure the distribution of the national resources over the districts in accordance to need. It should give the districts more discretionary powers to spend these resources and to take measures to foster primary health care. To effectively control the districts, the district health management teams should be required to make plans for developing more community oriented primary health care. These plans must concern implementation of primary health care programmes that are based on available resources and on the support of the community, whose representatives should play a key role in developing the plans. Through community participation in joint planning, the poor and needy section of the population could then be targeted. This would allow the development of appropriate interventions devised to their need, thereby creating opportunities to promote equity. These plans can be used afterwards by the government for evaluation purposes.

Conclusion

For the pastoralists the Kenyan health system has serious shortcomings and services must be delivered under difficult circumstances. Often, the most basic requirements cannot be met, thus adding major problems to the daily struggle for life. We argue that the implementation of community based, integrated primary health care could contribute to remedying the inadequacies in the health system. To achieve this, it is necessary that the government gradually work towards an appropriate mix of types of decentralisation to the district level.

Whereas scarce resources and problems in the infrastructure may be major obstacles to improve service delivery to pastoralists, it is preferable to maintain a certain level of centralisation. Only the national government might be able to improve the infrastructure and to provide better financial conditions for service delivery. As to health care provision itself, however, decentralisation should be strongly advocated. Care delivery should be dealt with at the lowest, i.e. community level, in order to bring the services closer to the people. This way, physical accessibility will improve. In addition, it warrants a better link to the culture, routines and power structures of the communities. This requires that traditional health care workers, community health care workers and the community leadership should be involved.

In conclusion, in order to substantially improve the health care provision to pastoralist people, integration should be pursued on different levels: between the health care system and other systems such as the veterinary sector, between policy-making on the national and local level respectively, between the local health care and the local culture and power relations, between traditional and western oriented health care and between health care services as such. A first step to achieving this is for the central government to delegate the responsibility for the development of such an integrated, community-based primary health care delivery to the district level management, and, at the same time, take action to develop the coordination between health and other sectors and to monitor and protect the developments at the district level. For the time being, this is the best mix of types of decentralisation to achieve better accessibility and more equity in the Kenyan health system.

Contributor Information

Huka H. Duba, Department of Health, Organisation, Policy and Economics, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

Ingrid M. Mur-Veeman, Department of Health, Organisation, Policy and Economics, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

Arno van Raak, Department of Health, Organisation, Policy and Economics, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Vitae

Henry Huka Duba is born of pastoralist parenthood in Kenya. After graduating with a diploma in public health in 1984, he worked for the Kenyan Ministry of Health as a public health officer, especially in pastoralist districts of Northern Kenya, delivering preventive/promotive health care amongst pastoralists. He also worked five years in Moyale and Marsabit districts as a district public health worker. In the meantime he obtained a certificate in community health and a post-graduate certificate in health management. In 1988/1999 he followed the Master of Public Health course at the University of Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Ingrid Mur-Veeman is associate professor at the University of Maastricht, Faculty of Health Sciences, department of Health Organisation Policy and Economics. She holds a PhD in organisation sociology. She teaches organisational science and management, also in the Master of Public Health course. In addition, she is head of the Research Group Integrated Care. This group conducts both qualitative and quantitative studies on care innovation leading to integrated care to people with complex health problems. The group members address organisation and network research, international comparative studies and economic evaluations.

Arno van Raak is lecturer at the University of Maastricht, Faculty of Health Sciences, department of Health Organisation Policy and Economics. He holds a PhD in sociology. He teaches in the areas of management and control of health organisations and research methods. He is also a teacher in the Master of Public Health course and a member of the Research Group Integrated Care. He conducts research on network development and international comparisons.

References

- 1.Baxter P. Pastoralists are people. Why development for pastoralists, not the development of pastoralism? The Rural Extension Bulletin. 1994;4:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunton R, MacDonald B. Health promotion. Discipline and Diversity. New York: Routledge; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christian Children Fund Inc. General Survey Marsabit. 1992.

- 4.Collins CH, Green A. Decentralization and primary health care. International Journal of Health Services. 1994;24:459–75. doi: 10.2190/G1XJ-PX06-1LVD-2FXQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins DH, Quick J, Musau SN, Kraushaar DL. Health financing reform in Kenya: the fall and rise of cost sharing, 1989–94. Boston, MA: Management Sciences for Health, Stubbs Monograph Series Nr. 1; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green LW, Raeburn JM. Health promotion. What is it? Health Promotion. 1988;3:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helman CG. Culture Health and Illness. An Introduction for Health Professionals. Oxford: Biddles; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kar SB. Health promotion: indicators and actions. New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health. Introduction of cost-sharing in health service. Nairobi, Official Circular No. B/13/118B; 1989.

- 10.Ministry of Health. Kenya's Health Policy Framework. Nairobi: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Planning and National Development, Kenya. Marsabit Development Programme. Health and Nutrition Survey. 1994

- 12.Ministry of Planning and National Development, Kenya. Marsabit District Development Plan, 1994–1996. Nairobi: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Planning and National Development, Kenya. Marsabit District Development Plan, 1997–2001. 1997

- 14.Mwabu G, Wang'Ombe J. Financing rural health services in Kenya. Population Research and Policy Review. 1998;17:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omar MA. Health Care for Nomads. World Health Forum. 1992;13:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Republic of Kenya. Development plan, 1988–1993. Nairobi: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organisation. Health for all by the year 2000. World Health Assembly. Geneva: WHO; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Primary Health Care Concepts and Challenges in a changing World. Geneva: WHO; 1997. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1997/WHOARACC97.1.pdf. [Google Scholar]