Abstract

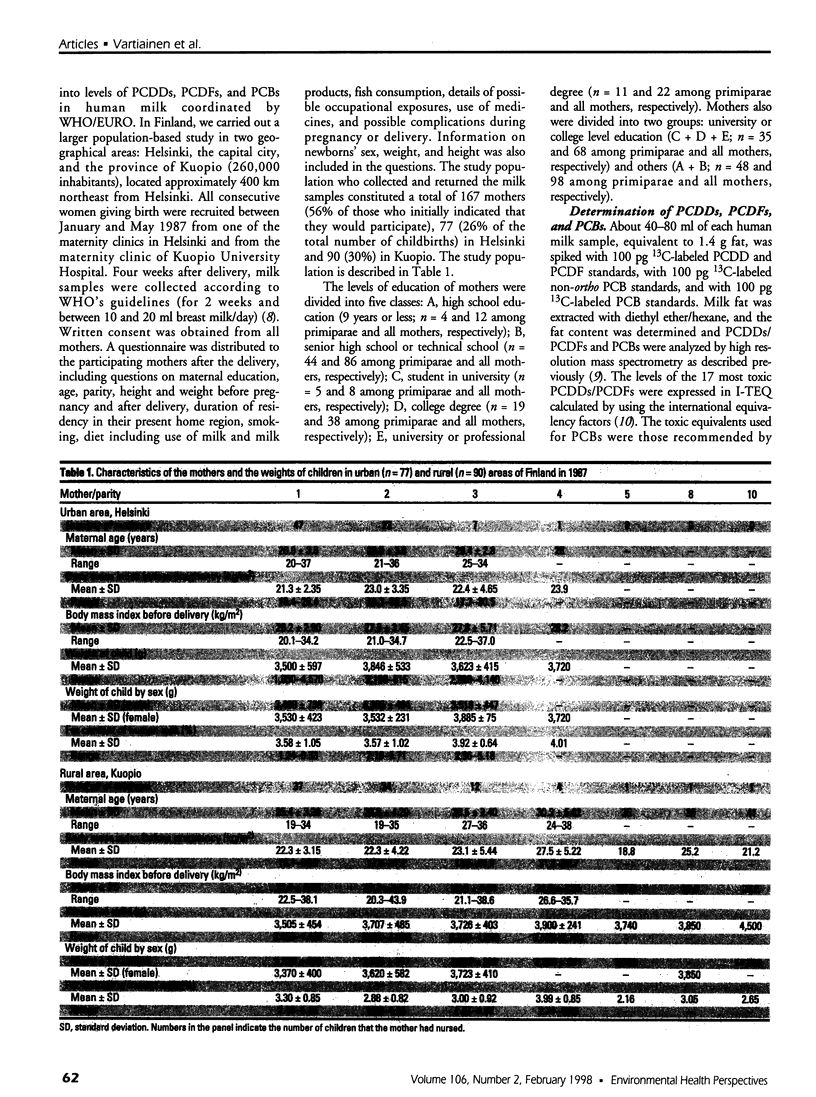

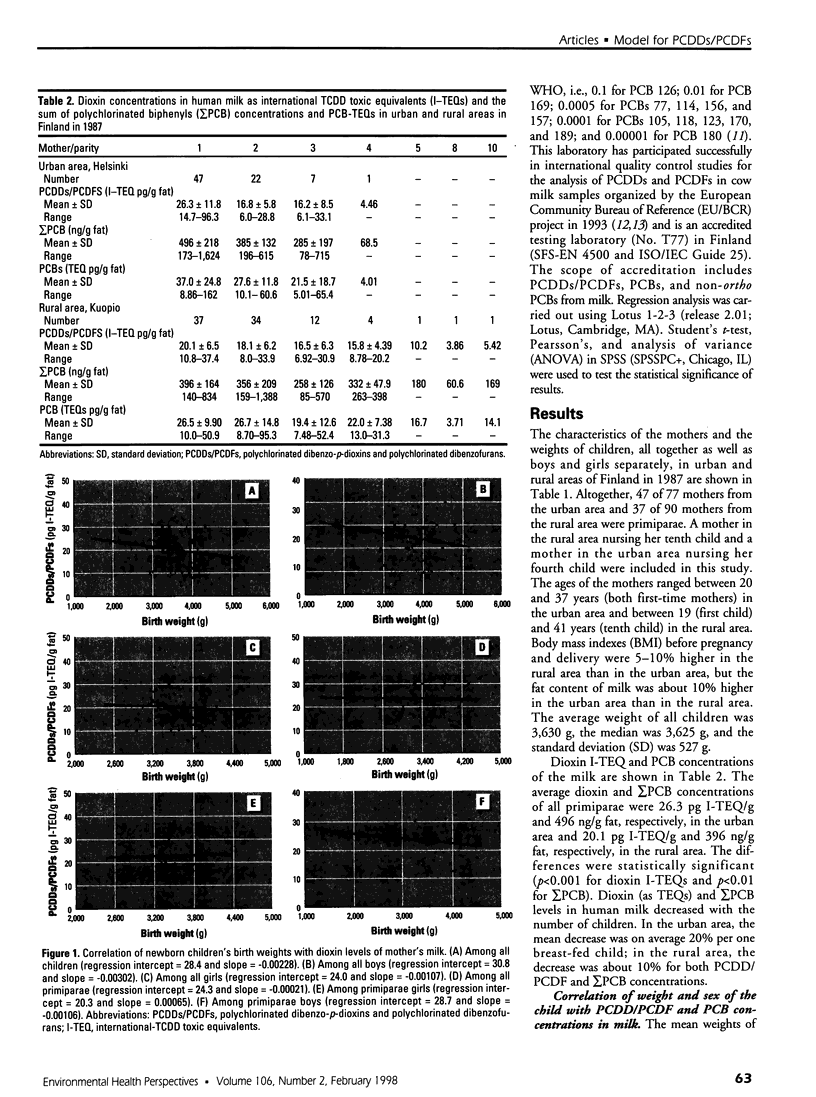

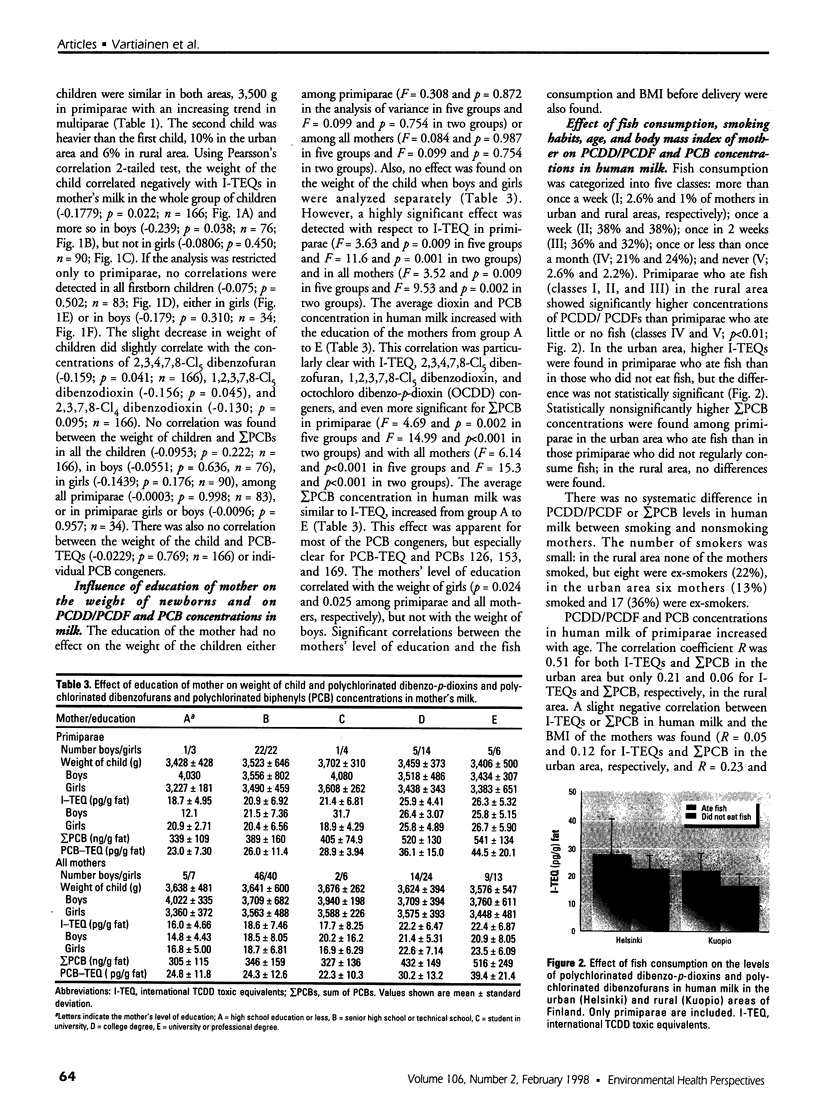

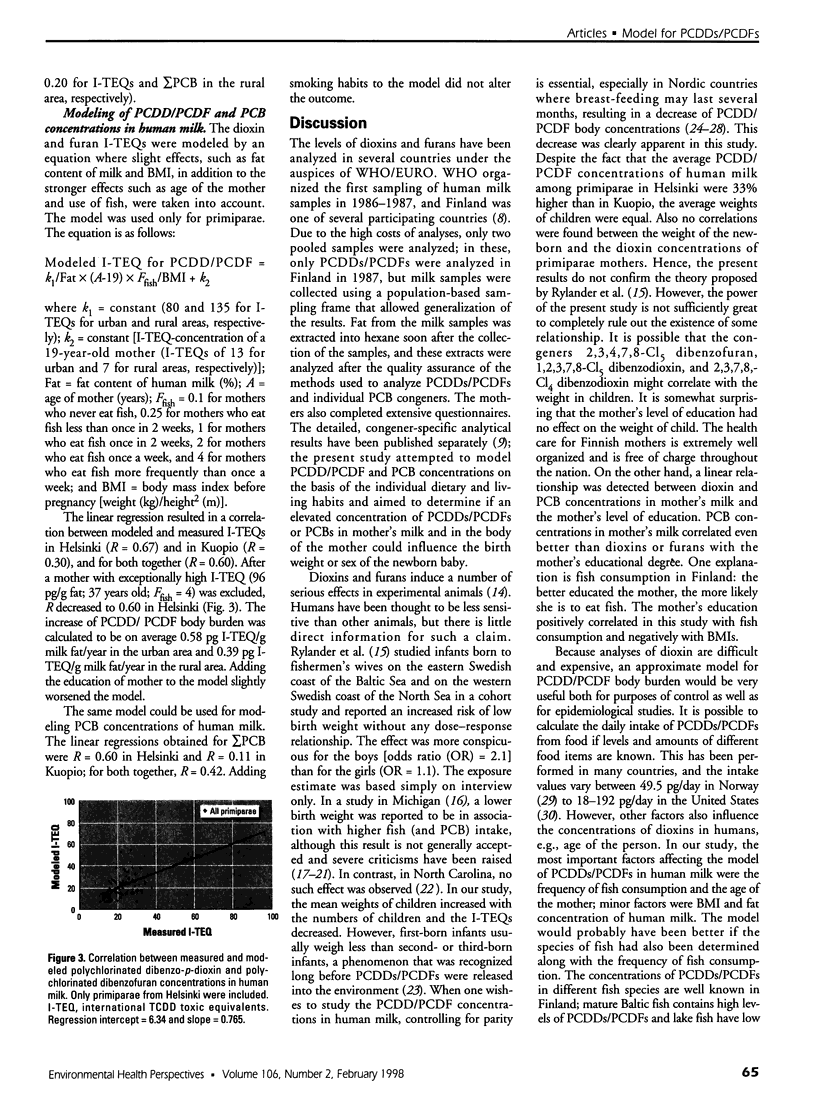

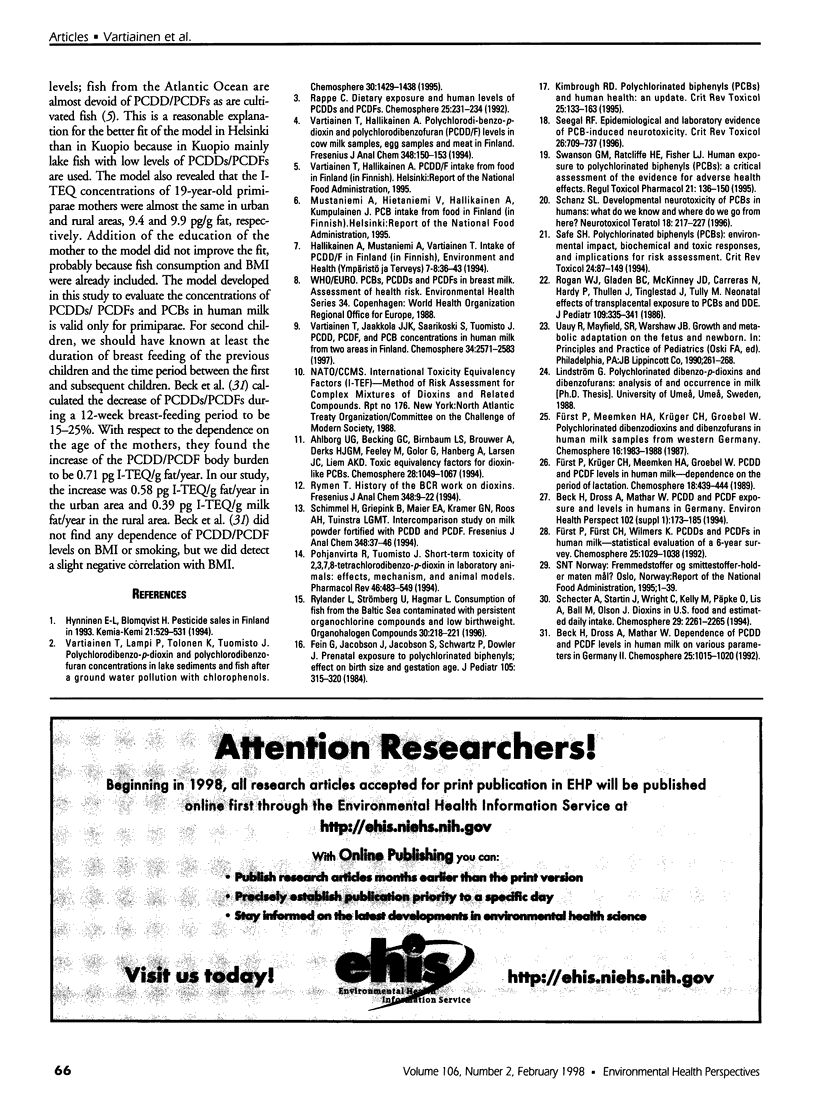

Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (PCDDs), polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PCDFs), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were analyzed in 167 random human milk samples from urban and rural areas in Finland. Dietary habits and background information on each mother and child were gathered by questionnaire. Body mass indexes (BMI) before pregnancy and delivery in the rural area were 5-10% higher than in the urban area, but fat content of mother's milk was about 10% higher in the urban area. The mean weights of children (+/- standard deviation) were similar in the rural and urban areas among primiparae, 3,500 +/- 597 g and 3,505 +/- 454 g, respectively, although dioxin international toxic equivalents (I-TEQs) were significantly higher in the urban area. The mother's level of education did not affect the weight of the child, but concentrations of PCDDs/PCDFs (I-TEQ, 2,3,4,7,8-Cl5 dibenzofuran,1,2, 3,7,8-Cl5 dibenzodioxin) and PCBs [sum of PCBs (sumPCB), PCB-TEQ, and most PCB congeners] increased with advanced education. This is considered to be due to differences in the mother's consumption of fish. The birth weight, especially of boys, slightly decreased with increasing concentrations of I-TEQ, 2,3,4,7,8-Cl5 dibenzofuran, 1,2,3, 7,8-Cl5 dibenzodioxin, and 2,3,7,8-Cl4 dibenzodioxin; however, when the analysis was restricted to primiparae, there was no statistically significant correlation between birth weight and the concentrations of PCDDs/PCDFs. No correlation was found between the weight of the child and PCBs, PCB-TEQs, or individual PCB congeners in the whole material or among primiparae, or among boys or girls. The concentrations of PCDDs/PCDFs and PCBs inhuman milk were modeled for primiparae by weighing fish consumption, age of mother, milk fat content, and BMI before pregnancy. The linear regression resulted in values of R = 0.67 and 0.30 for the modeled dioxin I-TEQs in the urban and rural areas, respectively, and the corresponding values for sumPCBs of R = 0.60 and 0.11. The increase of PCDD/PCDF body burden was calculated to be on average 0.58 pg I-TEQ/g milk fat/year in the urban area and 0.39 pg I-TEQ/g milk fat/year in the rural area.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beck H., Dross A., Mathar W. PCDD and PCDF exposure and levels in humans in Germany. Environ Health Perspect. 1994 Jan;102 (Suppl 1):173–185. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein G. G., Jacobson J. L., Jacobson S. W., Schwartz P. M., Dowler J. K. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: effects on birth size and gestational age. J Pediatr. 1984 Aug;105(2):315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrough R. D. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and human health: an update. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1995;25(2):133–163. doi: 10.3109/10408449509021611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanvirta R., Tuomisto J. Short-term toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in laboratory animals: effects, mechanisms, and animal models. Pharmacol Rev. 1994 Dec;46(4):483–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan W. J., Gladen B. C., McKinney J. D., Carreras N., Hardy P., Thullen J., Tinglestad J., Tully M. Neonatal effects of transplacental exposure to PCBs and DDE. J Pediatr. 1986 Aug;109(2):335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe S. H. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1994;24(2):87–149. doi: 10.3109/10408449409049308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schantz S. L. Developmental neurotoxicity of PCBs in humans: what do we know and where do we go from here? Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1996 May-Jun;18(3):217–276. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(96)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A., Startin J., Wright C., Kelly M., Päpke O., Lis A., Ball M., Olson J. Dioxins in U.S. food and estimated daily intake. Chemosphere. 1994 Nov-Dec;29(9-11):2261–2265. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(94)90393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegal R. F. Epidemiological and laboratory evidence of PCB-induced neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1996 Nov;26(6):709–737. doi: 10.3109/10408449609037481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson G. M., Ratcliffe H. E., Fischer L. J. Human exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): a critical assessment of the evidence for adverse health effects. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1995 Feb;21(1):136–150. doi: 10.1006/rtph.1995.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen T., Lampi P., Tuomisto J. T., Tuomisto J. Polychlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and polychlorodibenzofuran concentrations in human fat samples in a village after pollution of drinking water with chlorophenols. Chemosphere. 1995 Apr;30(8):1429–1438. doi: 10.1016/0045-6535(95)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartiainen T., Saarikoski S., Jaakkola J. J., Tuomisto J. PCDD, PCDF, and PCB concentrations in human milk from two areas in Finland. Chemosphere. 1997 Jun;34(12):2571–2583. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(97)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]