Abstract

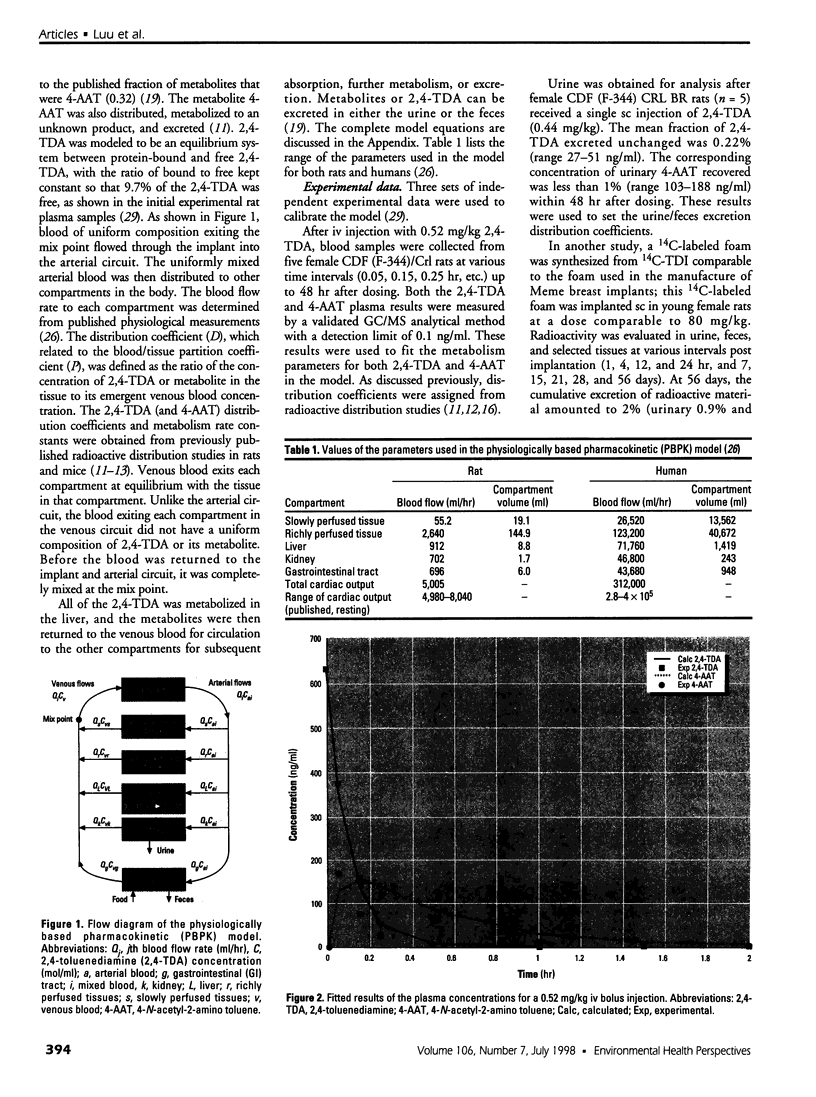

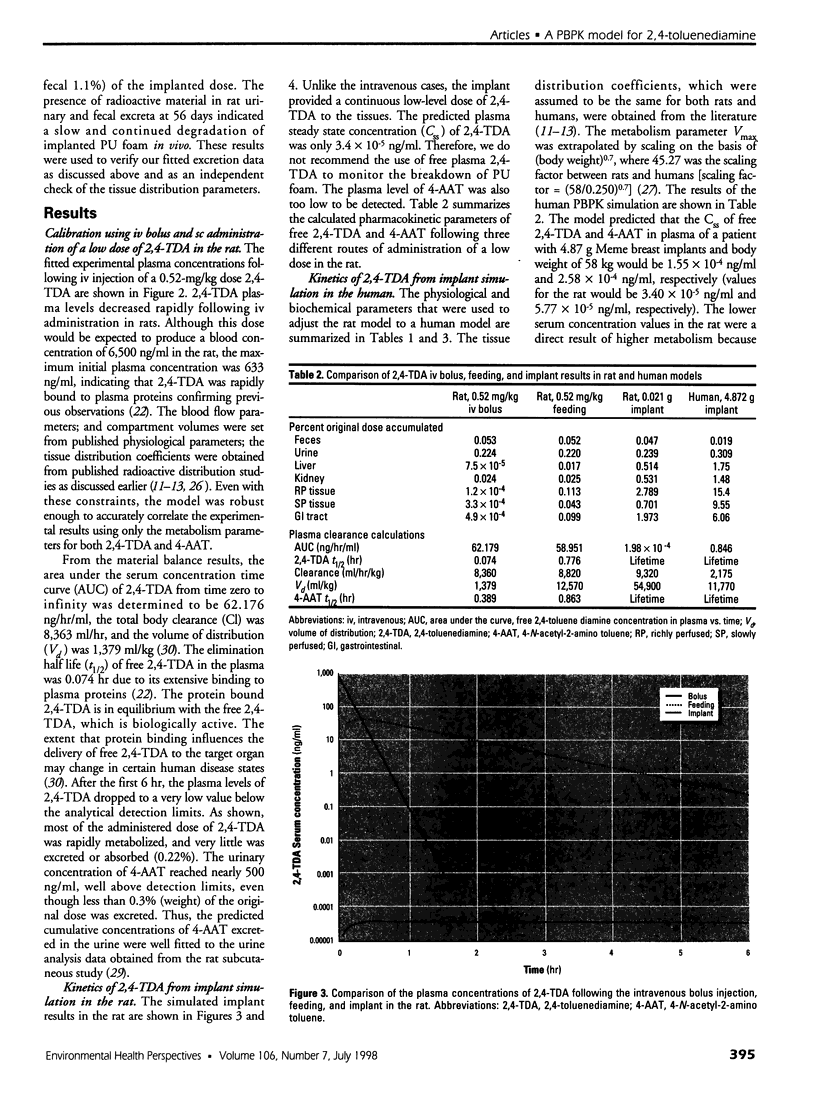

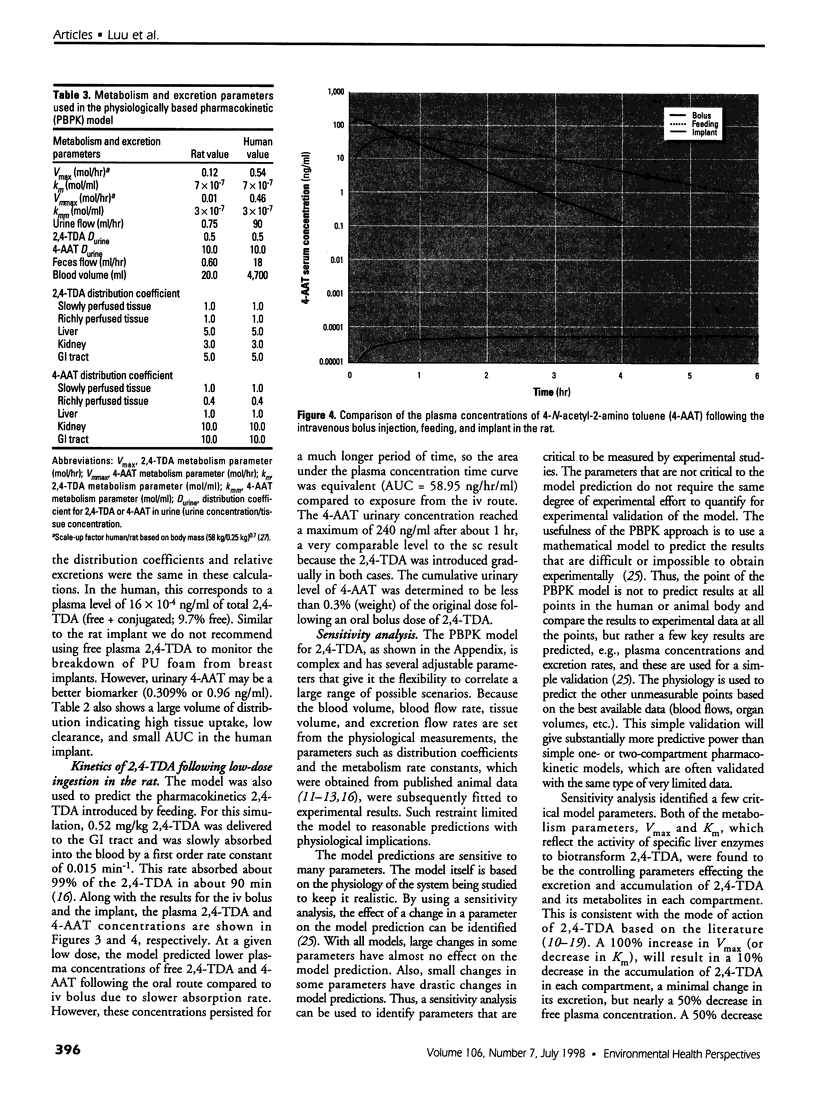

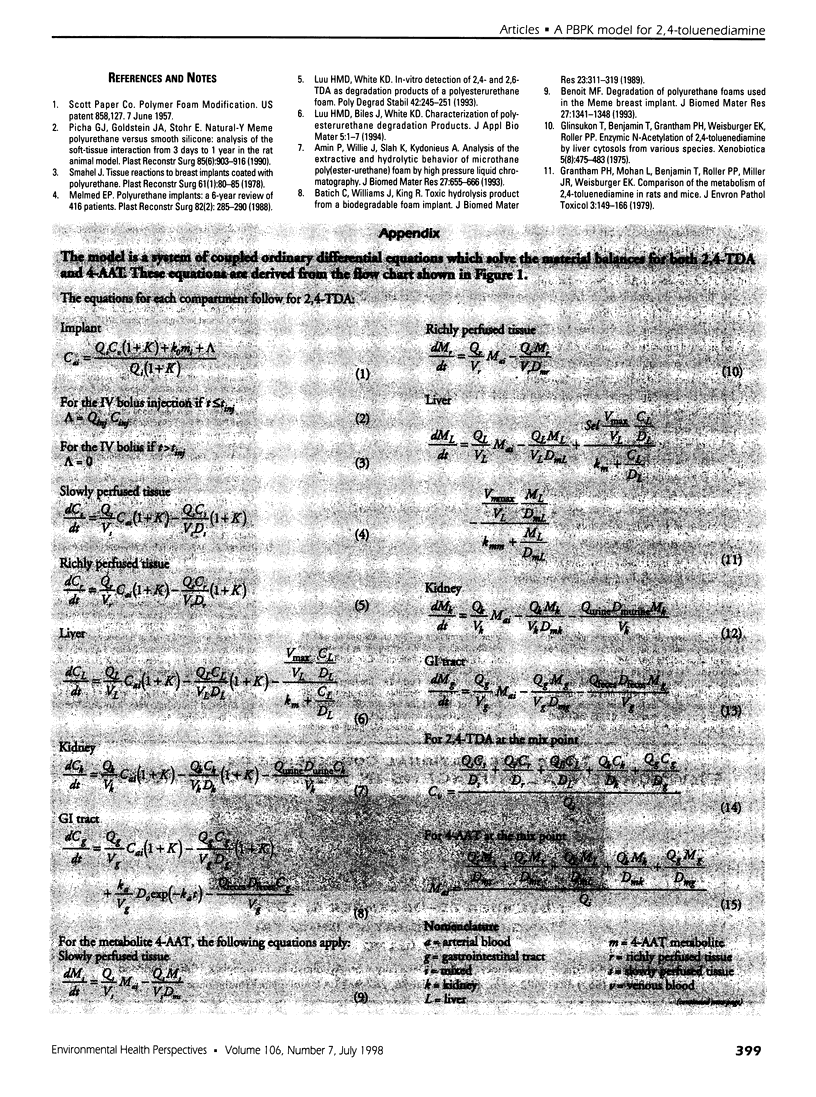

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling was used to assess the low-dose exposure of patients to the carcinogen 2, 4-toluenediamine (2,4-TDA) released from the degradation of the polyester urethane foam (PU) used in Meme silicone breast implants. The tissues are represented as five compartments: liver, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, slowly perfused tissues (e.g., fat), and richly perfused tissues (e.g., muscle). The PBPK model was fitted to the plasma and urine concentrations of 2,4-TDA and its metabolite 4-AAT (4-N-acetyl-2-amino toluene) in rats given low doses of 2, 4-TDA intravenously and subcutaneously. The rat model was extrapolated to simulate oral and implant routes in rats. After adjusting for human physiological parameters, the model was then used to predict the bioavailability of 2,4-TDA released from a typical 4.87-g polyester urethane foam implant found in a patient who weighed 58 kg with the Meme and had the breast implant for 10 years. A quantitative risk assessment for 2,4-TDA was performed and the polyester urethane foam did present an unreasonable risk to health for the patient.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amin P., Wille J., Shah K., Kydonieus A. Analysis of the extractive and hydrolytic behavior of microthane poly(ester-urethane) foam by high pressure liquid chromatography. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993 May;27(5):655–666. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. E., Clewell H. J., 3rd, Gargas M. L., Smith F. A., Reitz R. H. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics and the risk assessment process for methylene chloride. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1987 Feb;87(2):185–205. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batich C., Williams J., King R. Toxic hydrolysis product from a biodegradable foam implant. J Biomed Mater Res. 1989 Dec;23(A3):311–319. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820231406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit F. M. Degradation of polyurethane foams used in the Même breast implant. J Biomed Mater Res. 1993 Oct;27(10):1341–1348. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. P., Delp M. D., Lindstedt S. L., Rhomberg L. R., Beliles R. P. Physiological parameter values for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Toxicol Ind Health. 1997 Jul-Aug;13(4):407–484. doi: 10.1177/074823379701300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. C., Birdsell D. C., Gradeen C. Y. Detection of toluenediamines in the urine of a patient with polyurethane-covered breast implants. Clin Chem. 1991 May;37(5):756–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. C., Birdsell D. C., Gradeen C. Y. Urinary excretion of free toluenediamines in a patient with polyurethane-covered breast implants. Clin Chem. 1991 Dec;37(12):2143–2145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinsukon T., Benjamin T., Grantham P. H., Weisburger E. K., Roller P. P. Enzymic N-acetylation of 2,4-toluenediamine by liver cytosols from various species. Xenobiotica. 1975 Aug;5(8):475–483. doi: 10.3109/00498257509056118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham P. H., Mohan L., Benjamin T., Roller P. P., Miller J. R., Weisburger E. K. Comparison of the metabolism of 2,4-toluenediamine in rats and mice. J Environ Pathol Toxicol. 1979 Dec;3(1-2):149–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N., Hiasa Y., Konishi Y., Marugami M. The development of carcinoma in liver of rats treated with m-toluylenediamine and the synergistic and antagonistic effects with other chemicals. Cancer Res. 1969 May;29(5):1137–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melmed E. P. Polyurethane implants: a 6-year review of 416 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988 Aug;82(2):285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picha G. J., Goldstein J. A., Stohr E. Natural-Y Même polyurethane versus smooth silicone: analysis of the soft-tissue interaction from 3 days to 1 year in the rat animal model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990 Jun;85(6):903–916. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J. C., Andersen M. E. A physiologically based description of the inhalation pharmacokinetics of styrene in rats and humans. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1984 Mar 30;73(1):159–175. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepai O., Henschler D., Czech S., Eckert P., Sabbioni G. Exposure to toluenediamines from polyurethane-covered breast implants. Toxicol Lett. 1995 May;77(1-3):371–378. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smahel J. Tissue reactions to breast implants coated with polyurethane. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978 Jan;61(1):80–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timchalk C., Smith F. A., Bartels M. J. Route-dependent comparative metabolism of [14C]toluene 2,4-diisocyanate and [14C]toluene 2,4-diamine in Fischer 344 rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1994 Feb;124(2):181–190. doi: 10.1006/taap.1994.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring R. H., Pheasant A. E. Some phenolic metabolites of 2, 4-diaminotoluene in the rabbit, rat and guinea-pig. Xenobiotica. 1976 Apr;6(4):257–262. doi: 10.3109/00498257609151635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisburger E. K., Russfield A. B., Homburger F., Weisburger J. H., Boger E., Van Dongen C. G., Chu K. C. Testing of twenty-one environmental aromatic amines or derivatives for long-term toxicity or carcinogenicity. J Environ Pathol Toxicol. 1978 Nov-Dec;2(2):325–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]