Abstract

Sex pheromone plasmids, frequently found in Enterococcus faecalis, have rarely been detected in Enterococcus faecium. pBRG1 is an approximately 50-kb vanA-carrying conjugative plasmid of an E. faecium clinical isolate (LS10) that is transferable to E. faecalis laboratory strains. In cell infection experiments, E. faecium LS10 exhibited remarkably high invasion efficiency and produced cytopathogenic effects in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Growth in the presence of sex pheromones produced by E. faecalis JH2-2 was found to cause self-aggregation of both E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) (a transconjugant obtained by transfer of pBRG1 to E. faecalis JH2-2) and to increase the cell adhesion and invasion efficiencies of both E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1). Sex pheromone cCF10 caused clumping of E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) (a transconjugant obtained by transfer of pBRG1 to E. faecalis OG1RF) at a concentration ∼100-fold higher than the one required for the control strain E. faecalis OG1RF(pCF10). PCR products of the expected sizes were obtained with primers internal to aggregation substance genes of E. faecalis pheromone response plasmids pAD1, pPD1, and pCF10 and primers internal to ash701 of E. faecium pheromone plasmid pHKK701. These findings suggest that pBRG1 of E. faecium LS10 is a sex pheromone response plasmid.

Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, enterococci have gradually become important nosocomial pathogens, and multidrug-resistant enterococcal strains are now a leading cause of hospital-acquired infection (20). Enterococcus faecalis causes 80 to 90% of human enterococcal infections, and Enterococcus faecium causes the majority of the remainder (other enterococcal species being infrequent causes of infection in humans) (17). In enterococci, in particular E. faecium, the emergence and dissemination of high-level resistance to glycopeptides have resulted in clinical isolates resistant to all antibiotics of proven efficacy (4, 30). VanA is the most frequently reported phenotype; it is associated with high-level resistance to vancomycin and cross-resistance to teicoplanin, and it is transferable by conjugation (4).

The high incidence of antibiotic-resistant enterococci involved in nosocomial infections seems to be at least partly due to their natural ability to acquire extrachromosomal elements encoding antibiotic resistance (20). Interestingly, the same mobile extrachromosomal elements carrying antibiotic resistance genes may also code for virulence traits (17, 22), such as aggregation substance (AS), a surface protein encoded by pheromone response plasmids (33).

The sex pheromone response system, first described in 1978 (9), is highly specific for E. faecalis and is related to virulence (6, 36). Pheromone-induced conjugal transfer in E. faecalis involves the production of sex pheromones by the recipient and the subsequent recognition of these pheromones by the donor; each pheromone is specific for a particular plasmid or group of related plasmids (8). In response to pheromones, cells form clumps (aggregates) in broth. Aggregation is mediated by AS, and its expression is induced by the specific pheromone. Besides facilitating the conjugative exchange of plasmids, such as plasmids carrying virulence traits and/or antibiotic resistance genes (6, 22, 36), AS promotes E. faecalis adhesion to and internalization into cultured human cells (5, 24, 28, 35) as well as intracellular survival within macrophages (31). Very recent data suggest that AS might play an indirect role in invasion, possibly simply by increasing the number of organisms taken up as a clump (C. M. Waters, C. L. Wells, and G. M. Dunny, Abstr. 6th Am. Soc. Microbiol. Conf. Streptococcal Genetics, abstr. 121, 2002).

Several distinct sex pheromone plasmids coding for similar aggregation proteins have been described in E. faecalis (6, 33, 36). AS-encoding genes from three pheromone plasmids, pCF10, pAD1, and pPD1, have been sequenced (14, 15, 23), and regions of high conservation have been used to generate primers for AS (12). Conversely, sex pheromone plasmids have rarely been described in E. faecium: interestingly, both pheromone response plasmids described in this species are associated with vancomycin resistance (18, 19).

In the present study, we report the discovery of another pheromone response plasmid of E. faecium associated with vancomycin resistance. This plasmid (pBRG1) is the vanA-carrying conjugative plasmid harbored by the previously described clinical isolate E. faecium LS10 (1, 7).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

A total of 14 strains, including 11 enterococci and 3 listeriae, were used. The strains and their relevant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Enterococci included six vancomycin-resistant clinical isolates (two E. faecium, two E. faecalis, and two E. durans, all displaying the VanA resistance phenotype) and five laboratory strains of E. faecalis. Among clinical isolates, E. faecium LS10 was isolated in 1991 from an infected burn: it is known to harbor a vanA-carrying conjugative plasmid (herein called pBRG1) of about 50 kb transferable to E. faecalis and to listeriae of different species (1); E. faecalis LS4 was isolated in 1991 from catheter-related endocarditis in a transplanted heart (32): it is also known to harbor a vanA-carrying conjugative plasmid (1); the remaining strains were recently isolated from clinical specimens. Identification was performed with API 20 Strep galleries (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and confirmed by conventional laboratory tests. Among laboratory strains, E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) is a vanA transconjugant, previously obtained by conjugative transfer of pBRG1 to E. faecalis JH2-2 (1), whereas E. faecalis OG1RF is a well-characterized pheromone-producing strain, and OG1RF(pCF10) is its derivative containing a pheromone-susceptible plasmid (11). Listerial strains were used in internalization experiments as controls of invasion. Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 43249 is an invasive, hemolytic strain capable of multiplying intracellularly; L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248 is a spontaneous nonhemolytic variant capable of invading but not of multiplying intracellularly; and L. innocua NCTC 11288 is the type strain of the noninvasive species L. innocua.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or referenceb |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecium LS10 | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying conjugative plasmid, pBRG1 (∼50 kb) | Infected burn (1, 7) |

| E. faecium 31E | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying plasmid | Blood (this study) |

| E. faecalis LS4 | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying plasmid | Central venous catheter (1, 32) |

| E. faecalis 24E | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying plasmid | Urine (this study) |

| E. durans 26E | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying plasmid | Blood (this study) |

| E. durans PV1 | Vmr; contains a vanA-carrying plasmid | Abortion (this study) |

| E. faecalis JH2-2 | Fusr Rifr; sex pheromone producer, used as recipient in conjugation experiments | 21 |

| E. faecalis OG1RF | Fusr Rifr; sex pheromone producer, used as recipient in conjugation experiments | 11 |

| E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) | Vmr Fusr Rifr; contains pBRG1 | Conjugation: E. faecium LS10 × E. faecalis JH2-2 (1) |

| E. faecalis OG1RF (pCF10) | Contains the sex pheromone response plasmid pCF10 | 11 |

| E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) | Vmr Fusr Rifr; contains pBRG1 | Conjugation: E. faecium LS10 × E. faecalis OG1RF (this study) |

| L. monocytogenes ATCC 43249 | Invasive, hemolytic, capable of intracellular multiplication | ATCC |

| L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248 | Invasive, nonhemolytic | ATCC |

| L. innocua NCTC 11288T | Noninvasive | NCTC |

Vmr, vancomycin resistant; Fusr, fusidic acid resistant; Rifr rifampin resistant.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; NCTC, National Collection of Type Cultures, Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom

Brain heart infusion (BHI) broth and agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and blood agar base (BAB; Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% defribinated sheep blood were used for routine growth. Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Oxoid) was used in microtiter clumping assays. All laboratory-derived strains were obtained and carefully stored in our laboratory.

Antibiotics and susceptibility testing.

Vancomycin and teicoplanin were obtained from Eli Lilly (Florence, Italy) and Aventis Pharma (Milan, Italy), respectively. MICs were determined according to standard procedures recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (27). Mueller-Hinton broth or agar (Difco) supplemented with 5% sheep blood was used as the test medium.

Plasmid analysis, hybridization, and conjugation experiments.

Plasmid DNA analysis, hybridization, and conjugation experiments were performed as described previously (1).

PCR and restriction analysis of PCR products.

Total DNA extraction, primers, and DNA amplification of the vanA gene were done as described previously (2). The primers and DNA amplification technique used for the AS genes (agg) of E. faecalis pheromone plasmids (pAD1, pPD1, and pCF10) were described by Eaton et al. (12) (with an expected product of 1,553 bp). Primers and DNA amplification of the AS gene of E. faecium plasmid pHKK701 (ash701) were designed on the basis of published (19) sequences (5′-ATACAAAGCCAATGTGG and 5′-TACAAACGGCAAGACAAG; expected product, 427 bp). Amplified DNA was separated on 1% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Amplicons were subjected to restriction analysis with DraI according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). GeneRuler 100-bp DNA Ladder Plus was used as a molecular weight marker. Gels were photographed under UV light with Polaroid B/W 667 film and an MP-4 Land camera.

Pheromones and clumping assays.

Enterococcal induction by growth in the presence of sex pheromones was essentially performed as described by Dunny et al. (9, 10). Pheromone preparations were culture filtrates of E. faecalis strains JH2-2 and OG1RF. In induction experiments, bacteria were grown in BHI broth to the late exponential phase and then diluted 1:10 into 10 ml of a 1:1 mixture of filtrate and fresh BHI broth. Bacteria were then incubated with shaking at 37°C for 45 min. After induction, bacteria were used in aggregation or cell infection experiments. Clumping was evaluated microscopically.

cCF10, a peptide sex pheromone produced by E. faecalis OG1RF that specifically induces transfer of pCF10 (25), was kindly supplied by G. M. Dunny (University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis). cCF10 was resuspended in dimethylformamide (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) (0.5 mg/ml) and then diluted in THB to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. cCF10 activity was detected by a microtiter clumping assay as described by Buttaro et al. (3).

Cells.

The human colon carcinoma enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2 (ATCC HTB37) was used between passages 29 and 40. The cells were routinely grown in 25-cm2 plastic tissue culture flasks (Corning Costar, Milan, Italy) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. The culture medium was Dulbecco's modified Eagle's minimum essential medium (DMEM) containing 25 mM glucose, 4 mM l-glutamine, and 3.7 mg of sodium bicarbonate per ml (Euroclone, West York, United Kingdom), with 1% nonessential amino acids supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Euroclone), 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml.

Infection of Caco-2 cells and recovery of viable intracellular bacteria by survival test.

Confluent cell monolayers were trypsinized; cells were then counted and adjusted to a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells per ml in culture medium. One milliliter of the cell suspension was dispensed into each 22-mm well of a 12-well tissue culture plate (Corning Costar) and then incubated to obtain semiconfluent monolayers. Cells were washed with unsupplemented DMEM before infection. After overnight growth in BHI broth (enterococci) or BAB supplemented with 5% sheep blood (listeriae), enterococci were incubated in BHI broth to the late exponential phase (∼5 × 108 bacteria per ml), whereas listeriae were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to an optical density at 540 nm (OD540) of 0.6 ± 0.02 (∼3 × 108 bacteria per ml). Then 1 ml of the suspension, suitably diluted in DMEM, was added to each well to obtain a multiplicity of infection of about 150 (enterococci) or 30 (listeriae) bacteria per cell. Penetration was allowed to occur for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, and then cell monolayers were washed and covered with culture medium containing bactericidal concentrations of gentamicin (10 μg/ml for listeriae and 100 μg/ml for enterococci) and penicillin (5 μg/ml) (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.). After 2 h (T2) and 24 h (T24) of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 with gentamicin and penicillin, cells were extensively washed and lysed in cold distilled water. The CFU of viable bacteria were counted after plating of suitable dilutions of the lysates on BHI agar and incubation for 24 to 36 h at 37°C. Each strain was tested in three separate assays on different days, each assay representing the average of triplicate wells. Cell invasion efficiency was established on the basis of the percentage of survivors (referred to the initial inoculum) recovered after the incubation of infected cells with gentamicin and penicillin, which are unable to reach intracellular bacteria.

Evaluation of bacterial adhesion to cells.

At the end of the 1-h infection period, bacteria associated with Caco-2 monolayers were evaluated both as CFU and by gram staining. In both cases, Caco-2 monolayers were infected as described above. Cells were then either lysed in cold distilled water or fixed with methanol for gram staining. In the former experiments, CFU were counted as described above; in the latter, stained monolayers grown on slides were examined microscopically. The percentage of Caco-2 cells with associated bacteria was determined by counting all Caco-2 cells in 10 random microscopic areas: a positive result was scored when there was at least one enterococcal cell per Caco-2 cell. The number of cell-associated bacteria for each strain was determined by examining 100 cells.

CPE in Caco-2 monolayers.

The ability of bacterial strains to produce a cytopathogenic effect (CPE) in Caco-2 monolayers was assessed with trypan blue as described previously (13). Monolayers were photographed at a magnification of ×100 by inverted microscopy with Kodak TMAX 100 professional film.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical tests were performed as described by Selvin (29). In the experiments measuring internalization and survival of enterococci and listeriae in Caco-2 cells, the invasion efficiencies of two distinct strains were compared according to proportion differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The hypothesis that the proportions were equal was checked with the z test. To analyze the influence of sex pheromones produced by E. faecalis on adhesion and invasion efficiency, counts of induced and uninduced bacteria were compared. The odds ratio (OR) was employed as a measure of the association between pheromone induction and ability to adhere to and invade Caco-2 cells. The OR of each strain approximates the relative abilities of adherence and invasion as follows: OR ≅ probability that an induced strain adheres to and invades cells/probability that an uninduced strain adheres to and invades cells.

The natural logarithm of the OR has an approximately normal distribution; this property was used to test the hypothesis that sex pheromone induction was unrelated to adhesion ability (Wald's test).

RESULTS

vanA-carrying plasmids in clinical enterococci and transfer of the vanA plasmid of E. faecium LS10 to E. faecalis OG1RF.

All clinical enterococci were resistant to vancomycin (MIC, ≥64 μg/ml) and teicoplanin (MIC, ≥16 μg/ml). Plasmid analysis and hybridization experiments demonstrated that they all harbored plasmid DNA strongly hybridizing with a probe specific for the vanA resistance determinant (data not shown). In conjugation experiments, pBRG1, the vanA-carrying plasmid of E. faecium LS10, was transferred to E. faecalis OG1RF at a frequency of 1.0 × 10−7.

Internalization and survival of enteroccocci in Caco-2 cells.

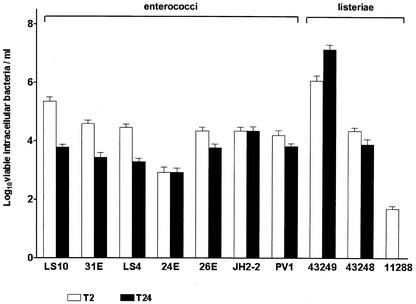

The six clinical enterococci, E. faecalis JH2-2, and the three listeriae were used to infect Caco-2 cells. As shown in Fig. 1, at T2, the common logarithm of the number of viable intracellular enterococci ranged from 2.9 (E. faecalis 24E) to 5.4 (E. faecium LS10), whereas that of viable listeriae was larger with L. monocytogenes ATCC 43249 and ATCC 43248 (6.1 and 4.4, respectively) than with L. innocua 11288T (1.7) (P < 0.0001). At T24, the common logarithm of the number of viable intracellular bacteria decreased to 3 in five enterococcal strains (3.8 for E. faecium LS10, E. durans 26E, and E. durans PV1; 3.4 for E. faecium 31E; and 3.3 for E. faecalis LS4) and in L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248 (3.9), and it remained unchanged in E. faecalis 24E and JH2-2, whereas it increased to 7.1 in L. monocytogenes ATCC 43249. No viable intracellular L. innocua cells were found at T24.

FIG. 1.

Enterococcal and listerial entry into and survival within Caco-2 cells. Shown are the numbers of viable intracellular bacteria after 2 h (T2) and 24 h (T24) of incubation with gentamicin and penicillin.

Clumping of pheromone-induced pBRG1-carrying strains.

The six enterococcal clinical strains, E. faecalis JH2-RFV(pBRG1), and E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) were microscopically examined for clumping after growth in the presence of pheromones of E. faecalis JH2-2. The activity of pheromone cCF10 on E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) was tested in a microtiter assay. E. faecalis OG1RF(pCF10) was used as a control for clumping.

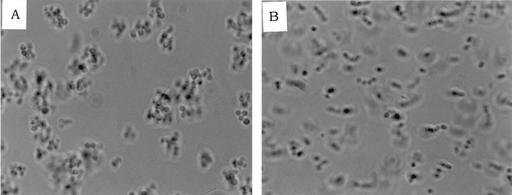

Growth of strains in the presence of pheromones of E. faecalis JH2-2 was found to cause clumping of pBRG1-carrying strains [E. faecium LS10, E. faecalis JH2-RFV(pBRG1), and E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1)] (Fig. 2), whereas growth in the presence of pheromones of E. faecalis OG1RF was found to have a barely detectable effect or no effect. Clumps of JH2-2-induced pBRG1-carrying strains were smaller than those obtained with the control strain OG1RF(pCF10).

FIG. 2.

Clumps of E. faecium LS10 after induction with sex pheromones from E. faecalis JH2-2. (A) Induced; (B) uninduced.

In microtiter assays, a positive clumping reaction required 3 μg of cCF10 per ml with E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) and 0.025 μg/ml with the control strain, OG1RF(pCF10).

Effects of induction with pheromones on adhesion and invasion efficiency of pBRG1-carrying strains.

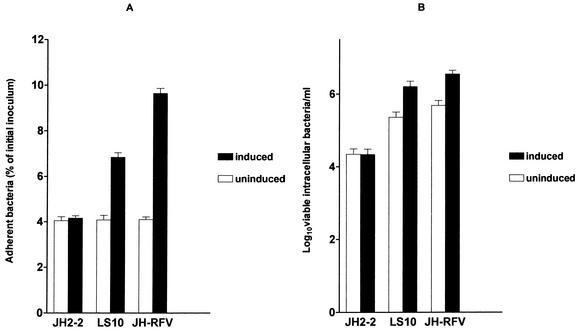

In cell infection experiments, E. faecium LS10, E. faecalis JH2-2, and E. faecalis JH2-RFV(pBRG1) were pregrown in pheromone-containing BHI broth from E. faecalis JH2-2 before infection of Caco-2 cells.

In adhesion experiments, a larger number of cells with associated bacteria and a larger number of bacteria per cell were observed after 1 h of infection in gram-stained monolayers with induced E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) than with the same strains uninduced or E. faecalis JH2-2. Approximately 50% of Caco-2 cells with associated bacteria (10 to >50 bacteria per cell) were observed when cells were infected with induced E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1), whereas approximately 13% of Caco-2 cells with associated bacteria (two to three bacteria per cell) were observed when cells were infected with uninduced E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) or with E. faecalis JH2-2. The numbers of adherent bacteria recovered after 1 h of infection with E. faecium LS10 and E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1) were 1.72 (95% CI, 1.723 to 1.725) and 2.522 (95% CI, 2.520 to 2.524) times greater (P < 0.0001), respectively, with induced strains than with the same strains uninduced (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Infection of Caco-2 cells before and after induction with sex pheromones from E. faecalis JH2-2. (A) Adhesion; (B) invasion.

In invasion experiments, the numbers of viable intracellular bacteria recovered at T2 from cells infected with induced bacteria were 6.896 (95% CI, 6.867 to 6.926) times (E. faecium LS10) and 7.224 (95% CI, 7.203 to 7.246) times [E. faecalis JH-RFV(pBRG1)] greater (P < 0.0001) than those with the same strains uninduced (Fig. 3B).

E. faecium LS10 causes moderate CPE in Caco-2 cell monolayers.

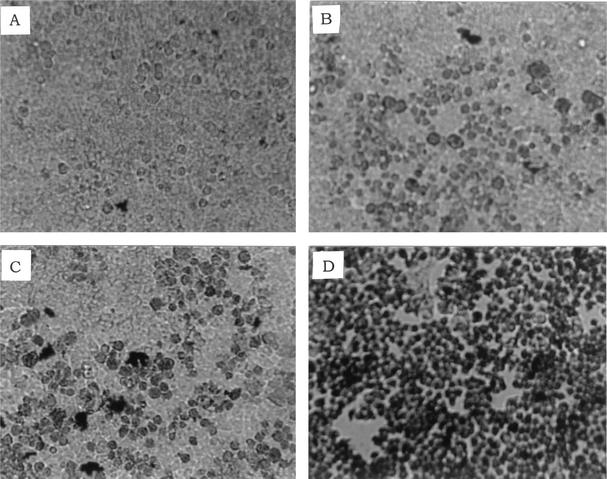

The viability of infected Caco-2 cells was assessed with trypan blue, which stains dead cells but is actively excluded from viable eukaryotic cells. In these experiments, the ability of E. faecium LS10 to cause CPE in Caco-2 monolayers was tested and compared with those of L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248 and ATCC 43249. E. faecium LS10 produced a moderate CPE. Monolayers infected with E. faecium LS10 and L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248 displayed scattered clusters of stained cells (∼15% of nonviable cells), whereas those infected with L. monocytogenes ATCC 43249 displayed large, almost contiguous stained areas (∼95% of nonviable cells) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

CPE in Caco-2 monolayers. CPE was assessed with trypan blue, which stains only dead cells. (A) Uninfected control; (B) E. faecium LS10; (C) L. monocytogenes ATCC 43248; (D) L. monocytogenes ATCC 43249. Magnification, ×100.

Presence of an AS gene in pBRG1.

An amplicon of approximately 1,550 bp was detected with the agg primers internal to the AS genes of E. faecalis pheromone response plasmids pAD1, pPD1, and pCF10 (expected size, 1,553 bp), whereas an amplicon of 427 bp was detected with the primers internal to ash701 of E. faecium plasmid pHKK701 (expected size, 427 bp) in E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1). Amplicons of the same sizes were detected in E. faecalis OG1RF(pCF10). DraI digests from 427-bp amplicons were identical in E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) and OG1RF(pCF10) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Evidence that enterococci can be efficiently internalized by nonphagocytic eukaryotic cells has been provided for E. faecalis (34), which is also able to survive in mouse peritoneal macrophages (16), but has not yet been provided for other enterococcal species. In the present study, six vancomycin-resistant enterococcal clinical isolates of three different species (E. faecium, E. faecalis, and E. durans) were investigated for their ability to enter and survive inside human cultured enterocytes (Caco-2). Plasmid analysis and hybridization experiments demonstrated that all six vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus clinical isolates harbored a vanA plasmid. All strains, independently of their clinical source, proved to be capable of penetrating and surviving within Caco-2 cells, exhibiting intracellular counts similar to those of invasive, nonhemolytic L. monocytogenes strain ATCC 43248, which enters the cells but is unable to multiply intracellularly. Our findings suggest that the ability to penetrate and survive inside human enterocytes may be a common feature of enterococci other than E. faecalis.

A significant result of the present study is the finding that pBRG1, the vanA-carrying plasmid of E. faecium LS10, is a pheromone response plasmid. E. faecium LS10 was more invasive than the other enterococcal strains, but its invasion efficiency was lower than that of an invasive, hemolytic L. monocytogenes strain (ATCC 43249) that actively multiplies intracellularly. Moreover, in infected monolayers, E. faecium LS10 produced a CPE similar to that produced by an invasive, nonhemolytic L. monocytogenes strain (ATCC 43248). These results suggest that E. faecium LS10 is unable to multiply intracellularly. Growth of E. faecium LS10 and a transconjugant obtained by transfer of pBRG1 to E. faecalis JH2-2 in the presence of sex pheromones produced by E. faecalis JH2-2 was found to cause clumping and an increase in cell adhesion and cell invasion efficiency. cCF10, a well-known sex pheromone, caused clumping of E. faecalis OG1RF(pBRG1) at a concentration ∼100-fold higher than the one required for E. faecalis OG1RF(pCF10). These results do not allow conclusive determination of whether pBRG1 specifically responds to cCF10. In other experiments, PCR products of the expected sizes were obtained with primers internal to the AS genes of the pheromone response plasmids of E. faecalis (pAD1, pPD1, and pCF10) and E. faecium (pHKK701). Only two other pheromone response plasmids, both associated with vancomycin resistance, have been described previously in E. faecium: one encoding vancomycin resistance (18) and one capable of mobilizing a coresident vancomycin resistance plasmid (19). In contrast, no pheromone response plasmids described in E. faecalis are known to confer glycopeptide resistance (26).

Although further work is needed to better characterize pBRG1 at the molecular level, our study suggests that pBRG1 encodes an AS involved in internalization into cultured intestinal epithelial cells, as previously demonstrated for the E. faecalis pheromone response plasmid pCF10, which encodes the Asc10 AS (28, 35). This study also suggests that the spread of plasmids carrying both vancomycin resistance and AS genes might contribute to the appearance of E. faecium strains with enhanced ability to cause disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. M. Dunny for kindly supplying E. faecalis strains OG1RF and OG1RF(pCF10) and a sample of sex pheromone cCF10.

This study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biavasco, F., E. Giovanetti, A. Miele, C. Vignaroli, B. Facinelli, and P. E. Varaldo. 1996. In vitro conjugative transfer of VanA vancomycin resistance between enterococci and listeriae of different species. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:50-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biavasco, F., A. Miele, C. Vignaroli, E. Manso, R. Lupidi, and P. E. Varaldo. 1996. Genotypic characterization of a nosocomial outbreak of vanA Enterococcus faecalis. Microb. Drug Res. 2:231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buttaro, B. A., M. H. Antiporta, and G. M. Dunny. 2000. Cell-associated pheromone peptide (cCF10) production and pheromone inhibition in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4926-4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cetinkaya, Y., P. Falk, and C. G. Mayhall. 2000. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:686-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow, J. W., L. A. Thal, M. B. Perri, J. A. Vazquez, S. M. Donabedian, D. B. Clewell, and M. J. Zervos. 1993. Plasmid-associated hemolysin and aggregation substance production contribute to virulence in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:2474-2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clewell, D. B., and G. M. Dunny. 2002. Conjugation and genetic exchange in enterococci, p. 265-300. In M. S. Gilmore (ed.), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 7.Conti, S., W. Magliani, S. Arseni, E. Dieci, R. Frazzi, A. Salati, P. E. Varaldo, and L. Polonelli. 2000. In vitro activity of monoclonal and recombinant yeast killer toxin-like antibodies against antibiotic-resistant gram-positive cocci. Mol. Med. 6:613-619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunny, G. M., M. H. Antiporta, and H. Hirt. 2001. Peptide pheromone-induced transfer of plasmid pCF10 in Enterococcus faecalis: probing the genetic and molecular basis for specificity of the pheromone response. Peptides 22:1529-1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunny, G. M., B. L. Brown, and D. B. Clewell. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3479-3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunny, G. M., R. A. Craig, R. L. Carron, and D. B. Clewell. 1979. Plasmid transfer in Streptococcus faecalis: production of multiple sex pheromones by recipients. Plasmid 2:454-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunny, G. M., C. Funk, and J. Adsit. 1981. Direct stimulation of the transfer of antibiotic resistance by sex pheromones in Streptococcus faecalis. Plasmid 6:270-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton, T. J., and M. J. Gasson. 2001. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1628-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facinelli, B., E. Giovanetti, G. Magi, F. Biavasco, and P. E. Varaldo. 1998. Lectin reactivity and virulence among strains of Listeria monocytogenes determined in vitro using the enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Microbiology 14:109-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galli, D., F. Lottspeich, and R. Wirth. 1990. Sequence analysis of Enterococcus faecalis aggregation substance encoded by the sex pheromone plasmid pAD1. Mol. Microbiol. 4:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galli, D., A. Friesenegger, and R. Wirth. 1992. Transcriptional control of sex-pheromone inducible genes on plasmid pAD1 of Enterococcus faecalis and sequence analysis of a third structural gene for (pPD1 encoded) aggregation substance. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1297-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentry-Weeks, C. R., R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. Pikis, M. Estay, and J. M. Keith. 1999. Survival of Enterococcus faecalis in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:2160-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock, L. E., and M. S. Gilmore. 2000. Pathogenicity of enterococci, p. 251-258. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 18.Handwerger, S., M. J. Pucci, and A. Kolokathis. 1990. Vancomycin resistance is encoded on a pheromone response plasmid in Enterococcus faecium 228. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:358-360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heaton, M. P., L. F. Discotto, M. J. Pucci, and S. Handwerger. 1996. Mobilization of vancomycin resistance by transposon-mediated fusion of a VanA plasmid with an Enterococcus faecium sex pheromone-response plasmid. Gene 171:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huycke, M. M., D. F. Sahm, and M. S. Gilmore. 1998. Multiple-drug resistant enterococci: the nature of the problem and an agenda for the future. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:239-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob, A. E., and S. J. Hobbs. 1974. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J. Bacteriol. 117:360-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jett, B. D., M. M. Huycke, and M. S. Gilmore. 1994. Virulence of enterococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kao, S.-M., S. B. Olmsted, A. S. Viksnins, J. C. Gallo, and G. M. Dunny. 1991. Molecular and genetic analysis of a region of plasmid pCF10 containing positive control genes and structural genes encoding surface proteins involved in pheromone-inducible conjugation in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 173:7650-7664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kreft, B., R. Marre, U. Schramm, and R. Wirth. 1992. Aggregation substance of Enterococcus faecalis mediates adhesion to cultured renal tubular cells. Infect. Immun. 60:25-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori, M., Y. Sakagami, Y. Ishii, A. Isogai, C. Kitada, M. Fujino, J. C. Adsit, G. M. Dunny, and A. Suzuki. 1988. Structure of cCF10, a peptide sex pheromone which induces conjugative transfer of the Streptococcus faecalis tetracycline resistance plasmid, pCF10. J. Biol. Chem. 263:14574-14578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mundy, L. M., D. F. Sahm, and M. Gilmore. 2000. Relationships between enterococcal virulence and antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:513-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 28.Olmsted, S. B., G. M. Dunny, S. L. Erlandsen, and C. L. Wells. 1994. A plasmid-encoded surface protein on Enterococcus faecalis augments its internalization by cultured epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1549-1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selvin, S. 1996. Statistical analysis of epidemiologic data. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 30.Spera, R. V., and B. F. Farber. 1992. Multiply-resistant Enterococcus faecium. The nosocomial pathogen of the 1990s. JAMA 268:2563-2564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sussmuth, S. D., A. Muscholl-Silberhorn, R. Wirth, M. Susa, R. Marre, and E. Rozdzinski. 2000. Aggregation substance promotes adherence, phagocytosis, and intracellular survival of Enterococcus faecalis within human macrophages and suppresses respiratory burst. Infect. Immun. 68:4900-4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venditti, M., F. Biavasco, P. E. Varaldo, A. Macchiarelli, L. De Biase, B. Marino, and P. Serra. 1993. Catheter-related endocarditis due to glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecalis in a transplanted heart. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:524-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weaver, K. E. 2000. Enterococcal genetics, p. 259-271. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 34.Wells, C. L., E. M. van de Westerlo, R. P. Jechorek, and L. S. Erlandsen. 1996. Intracellular survival of enteric bacteria in cultured human enterocytes. Shock 6:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells, C. L., E. A. Moore, J. A. Hoag, H. Hirt, G. M. Dunny, and S. L. Erlandsen. 2000. Inducible expression of Enterococcus faecalis aggregation substance surface protein facilitates bacterial internalization by cultured enterocytes. Infect. Immun. 68:7190-7194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wirth, R. 1994. The sex pheromone system of Enterococcus faecalis. More than just a plasmid-collection mechanism? Eur. J. Biochem. 222:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]