Abstract

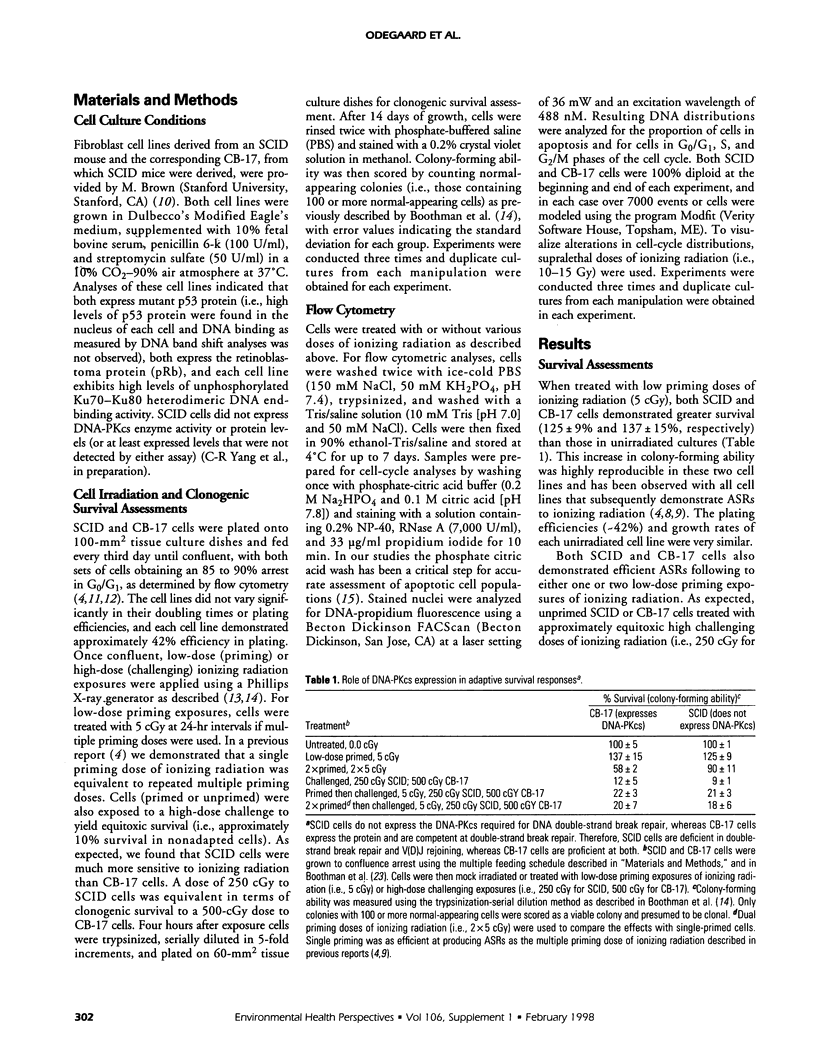

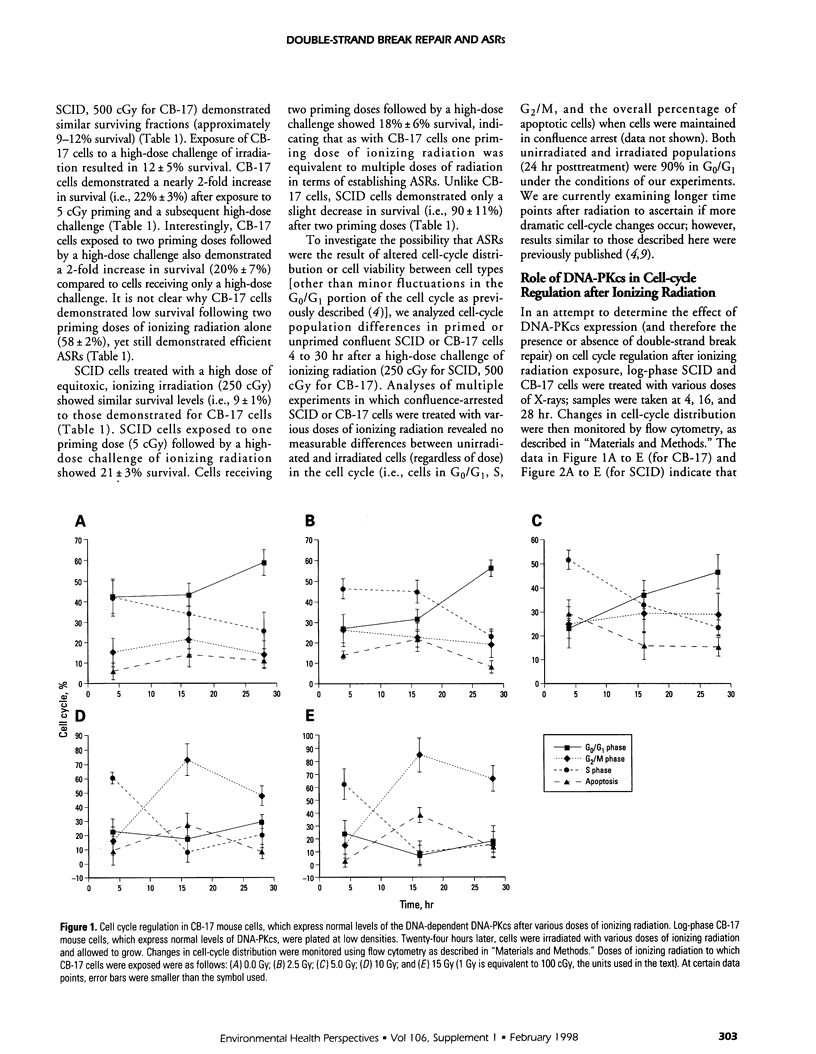

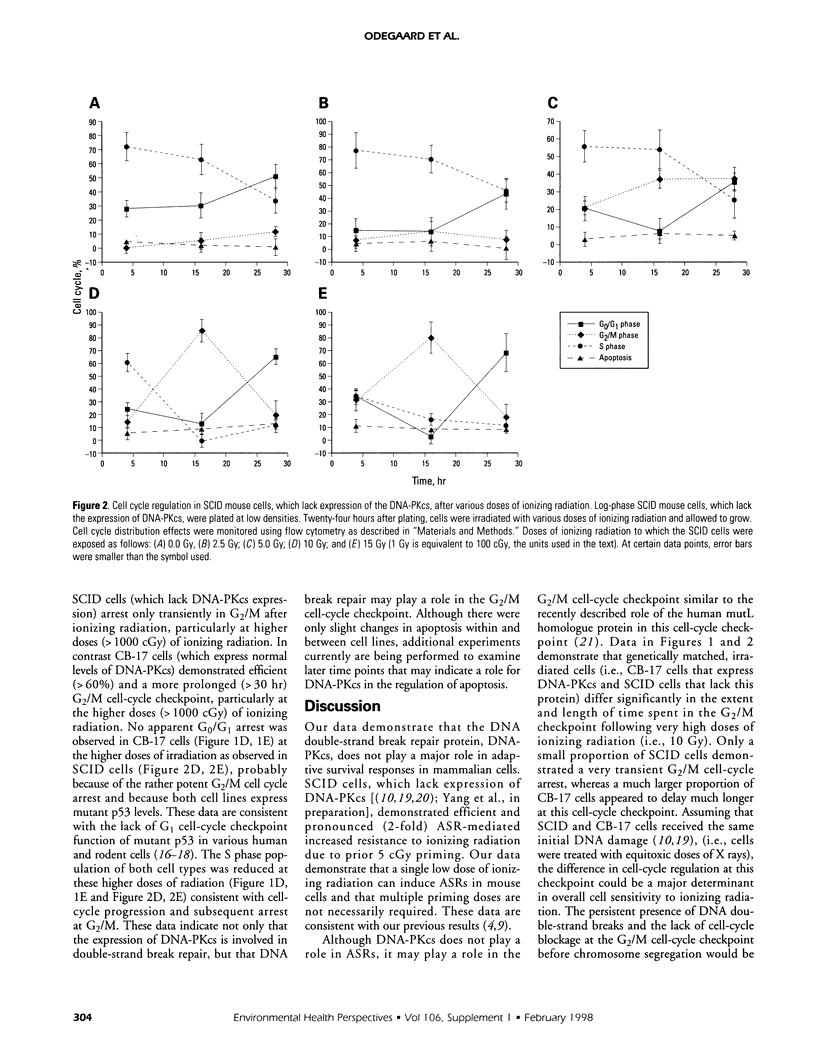

We previously demonstrated that exposure of certain human tumor cells to very low chronic doses of ionizing radiation led to their enhanced survival following exposure to subsequent high doses of radiation. Survival enhancement due to these adaptive survival responses (ASRs) ranged from 1.5-fold to 2.2-fold in many human tumor cells. Furthermore, we showed that ASRs result from altered G1 checkpoint regulation, possibly mediated by overexpression of cyclin D1, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and the X-ray induction of cyclin A. Because cyclin D1 and PCNA proteins are components of many DNA synthetic and repair processes in the cell, we tested the hypothesis that preexposure of cells to low doses of ionizing radiation enabled activation of the DNA repair machinery needed for survival recovery after high-dose radiation. We examined the role of DNA break repair in ASRs using murine cells deficient (i.e., severe combined immunodeficiency [SCID] cells) or proficient (i.e., parental mouse strain [CB-17] cells) in DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) expression and DNA double-strand break repair, DNA-PKcs is a nuclear serine/threonine protein kinase that is activated by DNA breaks and plays a key role in double-strand break repair. DNA-PKcs also phosphorylates several nuclear DNA-binding regulatory transcription factor proteins (e.g., Sp1 and p53), which suggests that DNA-PKcs may play a role in regulating transcription, replication, and recombination as well as DNA repair, after radiation. Therefore, we exposed confluent SCID or CB-17 cells to low priming doses of ionizing radiation (i.e., 5 cGy) and compared the survival responses of primed cells to those of unprimed cells after an equitoxic high-dose challenge. Low-dose-primed SCID or CB-17 cells demonstrated 2-fold enhanced survival after a high-dose challenge compared to that of unprimed control cells. These data suggest that expression of the catalytic subunit of DNA-PKcs (expressed in CB-17 not SCID cells) and the presence of active double-strand break repair processes (active in CB-17, deficient in SCID cells) do not play a major role in ASRs in mammalian cells. Furthermore, we present data that suggest that DNA-PKcs plays a role in the regulation of the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint following extremely high doses of ionizing radiation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Boothman D. A., Bouvard I., Hughes E. N. Identification and characterization of X-ray-induced proteins in human cells. Cancer Res. 1989 Jun 1;49(11):2871–2878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman D. A., Greer S., Pardee A. B. Potentiation of halogenated pyrimidine radiosensitizers in human carcinoma cells by beta-lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphtho[1,2-b]pyran- 5,6-dione), a novel DNA repair inhibitor. Cancer Res. 1987 Oct 15;47(20):5361–5366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman D. A., Meyers M., Odegaard E., Wang M. Altered G1 checkpoint control determines adaptive survival responses to ionizing radiation. Mutat Res. 1996 Nov 4;358(2):143–153. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(96)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman D. A., Pardee A. B. Inhibition of radiation-induced neoplastic transformation by beta-lapachone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(13):4963–4967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothman D. A., Trask D. K., Pardee A. B. Inhibition of potentially lethal DNA damage repair in human tumor cells by beta-lapachone, an activator of topoisomerase I. Cancer Res. 1989 Feb 1;49(3):605–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciola-Rosen L. A., Anhalt G. J., Rosen A. DNA-dependent protein kinase is one of a subset of autoantigens specifically cleaved early during apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1995 Dec 1;182(6):1625–1634. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. R., Lees-Miller S. P., Tegtmeyer P., Anderson C. W. The human DNA-activated protein kinase phosphorylates simian virus 40 T antigen at amino- and carboxy-terminal sites. J Virol. 1991 Oct;65(10):5131–5140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5131-5140.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan M. B., Zhan Q., el-Deiry W. S., Carrier F., Jacks T., Walsh W. V., Plunkett B. S., Vogelstein B., Fornace A. J., Jr A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell. 1992 Nov 13;71(4):587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgessner C. U., Patil C. K., Evans J. W., Cuomo C. A., Fried L. M., Carter T., Oettinger M. A., Brown J. M. DNA-dependent kinase (p350) as a candidate gene for the murine SCID defect. Science. 1995 Feb 24;267(5201):1178–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.7855601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgessner C. U., Tosto L. M., Biedermann K. A., Kovacs M., Araujo D., Stanbridge E. J., Brown J. M. Complementation of the radiosensitive phenotype in severe combined immunodeficient mice by human chromosome 8. Cancer Res. 1993 Dec 15;53(24):6011–6016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992 Jul 2;358(6381):15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. G., Kastan M. B. DNA strand breaks: the DNA template alterations that trigger p53-dependent DNA damage response pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1994 Mar;14(3):1815–1823. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchon S. M., Wuerzberger S., Frydman B., Witiak D. T., Hutson P., Church D. R., Wilding G., Boothman D. A. Beta-lapachone-mediated apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) and human prostate cancer cells: a p53-independent response. Cancer Res. 1995 Sep 1;55(17):3706–3711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadley J. D. Chromosomal adaptive response in human lymphocytes. Radiat Res. 1994 Apr;138(1 Suppl):S9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadley J. D., Dai G. Q. Cytogenetic and survival adaptive responses in G1 phase human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 1992 Feb;265(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(92)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadley J. D., Dai G. Evidence that the adaptive response of human lymphocytes to ionizing radiation acts on lethal damage in nonaberrant cells. Mutat Res. 1993 Mar;301(3):171–176. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(93)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. Adaptation to ionizing radiation induced by prior exposure to very low doses. Chin Med J (Engl) 1994 Jun;107(6):425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S., Afzal V., Jostes R. F., Wiencke J. K. Indications of repair of radon-induced chromosome damage in human lymphocytes: an adaptive response induced by low doses of X-rays. Environ Health Perspect. 1993 Oct;101 (Suppl 3):73–77. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101s373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S., Jostes R., Cross F. T., Hui T. E., Afzal V., Wiencke J. K. Adaptive response of human lymphocytes for the repair of radon-induced chromosomal damage. Mutat Res. 1991 Sep-Oct;250(1-2):299–306. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(91)90185-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]