Abstract

Human and mouse telomerases show a high degree of similarity in both the protein and RNA components. Human telomerase is more active and more processive than the mouse telomerase. There are two key differences between hTR [human TR (telomerase RNA)] and mTR (mouse TR) structures. First, the mouse telomerase contains only 2 nt upstream of its template region, whereas the human telomerase contains 45 nt. Secondly, the template region of human telomerase contains a 5-nt alignment domain, whereas that of mouse has only 2 nt. We hypothesize that these differences are responsible for the differential telomerase activities. Mutations were made in both the hTR and mTR, changing the template length and the length of the RNA upstream of the template, and telomerase was reconstituted in vitro using mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase generated by in vitro translation. We show that the sequences upstream of the template region, with a potential to form a double-stranded helix (the P1 helix) as in hTR, increase telomerase activity. The longer alignment domain increases telomerase activity only in the context of the P1 helix. Thus the TR contributes to regulating the level of activity of mammalian telomerases.

Keywords: human telomerase, in vitro reconstitution of telomerase, mouse telomerase RNA (mTR), RNA structure, telomerase, telomerase reverse transcriptase

Abbreviations: DTT, dithiothreitol; TR, telomerase RNA; hTR, human TR; mTR, mouse TR; RT, reverse transcriptase; TERT, telomerase RT; mTERT, mouse TERT; TRAP, telomeric repeat amplification protocol

INTRODUCTION

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme responsible for the maintenance of eukaryotic chromosome termini. The telomerase protein subunit {TERT [telomerase RT (reverse transcriptase)]} contains sequence motifs that are homologous with those found in retroviral RTs. The RNA subunit [TR (telomerase RNA)], which is essential for catalysis, contains the ‘template region’ [1] and is thought to directly participate in catalysis [2]. The template region is a short sequence on the TR that is copied repeatedly to produce the telomeric repeats at the ends of chromosomes.

A consensus vertebrate TR secondary structure has been described, in which the 5′-half of the RNA contains a pseudoknot and the template region, and the 3′-half contains a H/ACA box and CR4–CR5, a conserved bulge followed by a stem–loop. Box H/ACA, a motif that is typically found in small nucleolar RNAs, has been shown to be required for TR stability in vivo, but is dispensable for activity in vitro [3]. The CR4–CR5 helices are required for telomerase activity and assembly in vitro and in vivo [4,5]. The pseudoknot domain, which is also required for telomerase assembly and activity, is downstream of the template sequence [6,7]. The template itself contains separate alignment and templating motifs (Figure 1). The templating residues are the nucleotides that the telomerase copies. Upon completion of the synthesis of a single telomeric repeat, the telomerase undergoes a translocation to the start (the 3′-end) of the templating region, and the product is realigned with the template by base-pairing with the alignment motif so that a new repeat can be synthesized.

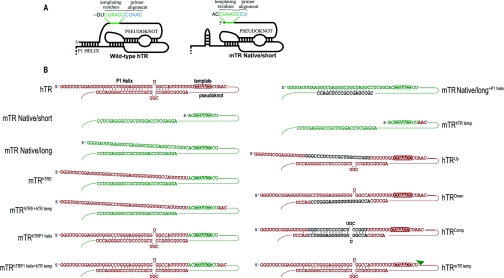

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the major differences between mTR and hTR, and the mutant transcripts used in the present study.

(A) Only the template, pseudoknot and P1 helix of each molecule, based on Chen et al. [6], are shown for clarity. The mTR shows a hairpin in the P1 region, which is predicted here by energy minimization using mfold [39]. The wild-type hTR contains a double-stranded extension 5′ of the template, which is absent from mTR, and the hTR template region is longer than the mTR template. The primer alignment and templating regions are indicated. (B) The sequence of the P1 and template region of each of the TRs tested is shown. The propensity of nucleotides within the P1 region to form complementary base-pairs is indicated. Sequence derived from mTR is coloured green and that from hTR is coloured red. The template sequence is indicated by inverse colouring.

Two mTR (mouse TR) transcripts with distinct 5′-termini have been reported in the literature. Initially, Blasco et al. [8] identified an approx. 430 base transcript containing 36 nt upstream of the template in D3 embryonic stem cells, which was confirmed by promoter analysis and similarity to hTR (human TR) [9]. In a subsequent report, the mTR transcript in NIH 3T3 cells was shown to contain only 2 nt upstream of the template sequence [10]. In the present study, we refer to these two transcripts as Native/long and Native/short mTRs. This contrasts with hTR, which has only one reported transcript with 45 nt 5′ of the template [11] and no obvious homology to the 36 nt of the longer mTR transcript.

Enzymatically active telomerase can be reconstituted from in vitro translated TERT protein and in vitro transcribed TR. This has been demonstrated for the telomerase from several organisms, including human [12–14], and the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila [15]. Mouse telomerase activity has also been reconstituted in vitro [4,16]. However, to date, the only reconstitution of mouse telomerase reported involved the use of two fragments of TR (mTR) separately comprising the pseudoknot and CR4–CR5 domains [4,17], which were shown to be the minimum required for the reconstitution of human telomerase activity [18].

Human telomerase is more processive and more active in vitro than mouse telomerase [16,19]. A hybrid telomerase enzyme containing the mouse protein component and hTR shows much higher levels of activity than either the reciprocal swap [14] or native mouse telomerase [20]. Therefore it appears that the differences in the in vitro activities of human and mouse telomerases are due to structural differences between the RNA moieties of the two enzymes.

The RNA components of telomerase from mouse (mTR) and human (hTR) are approx. 65% identical [8] [Supplementary Figure 1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/397/bj3970399add.htm) shows a comparison of the mouse and human telomerase components]. There are two essential differences between them: the length of the template region and the length of sequence upstream of the template (Figure 1A). Although both telomerases synthesize 6-nt repeats of the same sequence (TTAGGG), the template region of mTR is 3 nt shorter than that of hTR. The extra sequence in the hTR template forms a part of the alignment domain, which is 5 nt long in hTR and only 2 nt in mTR. The length of the alignment domain is hypothesized to be important in translocation processivity [8], as the alignment domain base-pairs with the translocated substrate. Secondly, while the mTR transcripts contain 2 or 36 nt upstream of the template region, the hTR contains 45 nt upstream of the template region. This upstream region of hTR potentially base-pairs with a downstream region, allowing the formation of a helical region, not present in mTR, termed the P1 helix. Furthermore, this P1 helix is predicted to be present in most vertebrate TRs [6]. However, there is no evidence of a P1 helix-forming potential for the longer mTR transcript. Even though there is a 36-nt extension upstream of the template region, it has no complementarity with the sequences downstream of the template region.

In the present study, we show that both the short and the long mTR transcripts co-exist within the mouse cells and present in vitro evidence demonstrating that the longer transcript does not produce active telomerase. In contrast with a previous effort [4] to reconstitute mouse telomerase activity using two fragments of mTR, we describe the use of full-length mTR that closely mimics the Native/short mTR. Finally, we elucidate the structural elements of mTR that are distinct from hTR, which may be responsible for its relatively lower level of activity compared with hTR in reconstitutions with the mTERT subunit.

EXPERIMENTAL

Plasmid construction

The mTERT coding sequence was PCR-amplified from a genomic clone (a gift from Dr Ron DePinho, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) and ligated into a pET24b expression vector (Novagen). The plasmid-encoded His tag was removed by insertion of an oligonucleotide (5′-TGAACCGGTACGTC) at the AatII site upstream of the hexahistidine coding sequence.

The mTR sequence was PCR-amplified from a genomic clone (a gift from Dr Ron DePinho) using primers 1a and 1b (see Table 1 for oligonucleotide sequences used in mTR plasmid construction). The vector fragment was created by PCR amplification of the pBluescript KS plasmid (Stratagene) using two adjacent primers 2a and 2b. These primers were used to create BsmBI and ScaI restriction sites at the termini of the resulting linearized plasmid. The mTR PCR product was digested with BsmBI, and the plasmid PCR product was digested with BsmBI and ScaI. The digestion products were ligated to create the wild-type mTR plasmid.

Table 1. Sequences of the oligonucleotides used in the construction of wild-type TR transcription templates.

| Primer | Sequence 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| 1a | CGGCCGTCTCTTATAACCTAACCCTGATTTTC |

| 1b | CTGAAGTACTAGCGGGAATGGGGGTTGTG |

| 2a | CCAACGTCTCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACGC |

| 2b | ACGTCCCGGGCTGCAGGAATTCGATATCAAGC |

| 3a | AGCGCGTCTCAGGGTATTTAAGGTCGAGGGC |

| 4a | TGAGCGTCTCAACCCTATAGTGAGTCG |

The mTR Native/long plasmid was constructed in a similar manner as the Native/short, but a different upstream primer (primer 3a) was used in the mTR PCR amplification. The vector was created by PCR amplification of pBluescript using the upstream primer 4a and the downstream primer 2b. The PCR products were restriction-digested and ligated as for Native/short to create pBluescriptmTR Native/long. All mTR PCR reactions were carried out using Clontech's GC melt PCR system; pBluescript amplifications used Turbo PFU (a thermostable polymerase; Stratagene). Construction of the hTR-encoding plasmid has been described previously [21]. All mutant mTR plasmids were generated via PCR and cassette mutagenesis [22,23]. The resulting transcripts are shown in Figure 1(B). All constructs were sequenced to ensure the absence of undesired mutations. The in vitro transcripts were characterized by sequence determination using AMV RT (Roche) and the primer CCCACAGCTAATGAAAATCAG.

In vitro transcription and translation

Reconstitution of active mouse telomerase was performed using TERT generated in vitro using TNT (an in vitro coupled transcription–translation kit; Promega) and TR transcribed from a T7 phage promoter using the Ampliscribe T7 in vitro transcription kit (Epicentre). Transcripts that contained a canonical T7 RNA polymerase promoter (i.e. those transcripts that contain a guanosine trinucleotide at the 5′-end) were transcribed as described by the manufacturer. Transcripts, which initiated with a non-standard sequence (which included the mTR Native/short transcripts, and variations thereof), were transcribed in reactions with double the normal concentration of both DNA template and T7 polymerase, and the reactions were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The templates for all transcription reactions were pBluescript-derived plasmids containing mTR sequences, linearized with ScaI. Transcripts were gel-purified on a 4% (w/v) denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and quantified by UV absorbance.

Translation reactions were set up as described by the manufacturer and incubated at 30 °C. After 2 h, fresh translation reaction buffer (a component of the TNT in vitro translation kit) and rabbit reticulocyte lysate were added, and mTR was added to a final concentration of 0.2 μM. The initial reaction volume was doubled while maintaining the original concentrations of reaction buffer and rabbit reticulocyte lysate. The reconstitution reaction was allowed to proceed for a further 90 min at 30 °C.

Multiplex RT–PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated from FM3A cells. cDNA was synthesized using Thermoscript RT (Invitrogen) at a temperature of 55 °C, using the reaction conditions recommended by the manufacturer, in 10 μl reaction volumes containing 6 μg of FM3A total cellular RNA or 1 fmol of in vitro-transcribed purified mTR Native/long RNA, and the primer 3′-RT (CCGGCGCCCCGCGGCTGACAGAG). PCR was performed in 5 μl reaction volumes containing 0.5 μl of each cDNA reaction and 2.5 pmol of 32P-labelled 3′-PCR primer (GCGGCAGCGGAGTCCTAAG), 0.5 μM 5′-a (5′-GAGGGCGGCTAGGCCTCGG), 0.5 μM 5′-b (5′-GCTGTGGGTTCTGGTCTTTTGTTC), 0.2 μM dNTPs, 0.1 unit of titanium Taq and 0.5 μl of reaction buffer (Clontech). Cycling conditions used were 94 °C 2 min, once; 94 °C 1 min, 62 °C 1 min, 68 °C 2 min, 25 times; 68 °C 5 min, once.

Telomerase activity assay

The telomerase assays used here are a modification of the TRAP (telomeric repeat amplification protocol) assay described by Kim and Wu [24], except for that used in Figure 4, where the dGTP was radiolabelled instead of the primer used in the PCR step. The Ts primer (5′-AATCCGTCGAGCAGAGTT-3′; described in [24]) was extended by telomerase in a 10 μl reaction containing 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM spermidine, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 10 μl of reconstituted proteinase inhibitor (Mini tablet-EDTA-free; Roche), 100 μM dTTP, 100 μM dATP, 100 μM dGTP and 180 nM 32P-labelled Ts oligonucleotide. Rabbit reticulocyte lysate, containing reconstituted telomerase, or S100 fraction (from HeLa or FM3A cell lysates), was added to this reaction, which was then incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. The positive control reaction contained R8 (Ts oligonucleotide containing eight telomeric repeats). The reactions were stopped by the addition of 40 μl of: 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 5.5 mM EDTA, 0.11% SDS and 130 ng of proteinase K (Ambion), and incubated at 55 °C for 30 min. The reaction was then phenol/chloroform-extracted, ethanol-precipitated and resuspended in 5 μl of 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0). The resuspended reaction products (2.5 μl) were combined with 2.5 μl of PCR reaction mixture to give final reaction conditions: 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 64 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.01% Tween 20, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 2 mM DTT, 100 μM dNTP, 200 nM ACX (PCR primer; 5′-GCGCGGCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTAACC-3′; described in [24]), 360 nM 32P-labelled Ts oligonucleotide and 0.1 μl/reaction Clontech titanium Taq. The PCR cycle conditions used were 94 °C 2 min, 1 cycle; 94 °C 30 s, 50 °C 30 s, 72 °C 45 s, 25 cycles; 72 °C 3 min, 1 cycle. PCR reaction products were separated by a 10% denaturing PAGE.

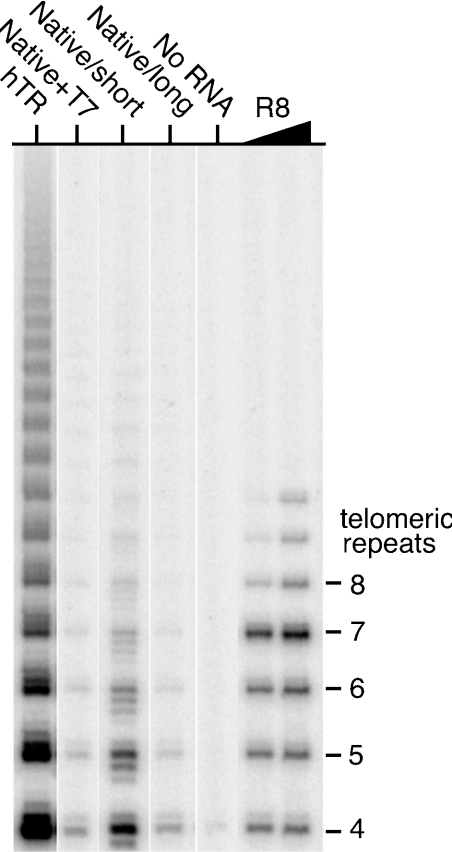

Figure 4. mTR Native/short is the active form of mTR.

The hTR, mTR with a 5′-extension of 4 nt (Native+T7), mTR Native/short (Native/short) and mTR Native/long transcripts were reconstituted with mTERT. TRAP assay was used to measure the telomerase activity of 0.2 μl of the reconstitution reaction, which contained the RNAs as labelled, and mTERT. The lane labelled R8 contains products from PCR amplification of a DNA oligonucleotide with eight telomeric repeats.

RESULTS

The relative abundance of the two mTR transcripts in murine cells

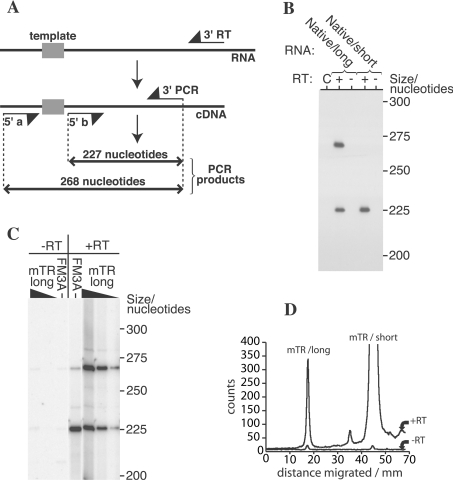

As the functional role of the two different mTR transcripts is unknown, the activity levels of mouse telomerase in cellular extracts could reflect the relative ratio of the two mTR transcripts in the cell. Therefore we wished to first determine the relative abundance of the two types of mTR transcripts in murine cells. A multiplex RT–PCR assay was designed to specifically detect both mTR transcripts in FM3A (a murine mammary carcinoma cell line). The first-strand synthesis was performed using a downstream primer complementary to the 3′ region of the mTR transcripts. PCR was then carried out on the resulting cDNA using two different upstream primers, a primer either complementary to the sequence immediately upstream of the template region, or complementary to sequence downstream from the template (Figure 2A). Thus the former primer will detect only those mTR transcripts that extend 5′ of the template region and the latter should detect any mTR transcripts that extend at least to the template region. After confirming the ability of this assay to detect the two types of mTRs using in vitro transcripts (Figure 2B), we used total RNA isolated from FM3A cells as template for the multiplex RT–PCR assay. Our results (Figure 2C) show that both mTR transcripts can be detected in FM3A cells. Quantification of the two bands, via phosphoimage analysis, showed that the longer transcript is between 2.5 and 10% of the more abundant shorter transcript (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. The mTR Native/short and mTR Native/long transcripts co-exist in murine cells.

(A) Reaction scheme, showing the size of the expected products from mTR with short or long extensions 5′ of the template. (B) Autoradiograph of PAGE showing the products of multiplex RT–PCR performed on in vitro transcribed mTR Native/long and Native/short. Fragments of the expected sizes can be seen. The left lane labelled C is the no RNA control. (C) Autoradiograph of PAGE showing the products of reaction performed on FM3A RNA and in vitro transcribed mTR Native/long (1–0.04 amol of RNA per reaction in the lanes labelled ‘mTR long’). The gel shows that a longer mTR transcript is present in FM3A cells, but constitutes a smaller fraction of total mTR. (D) Profiles generated from a phosphoimage of the gel in (C) using ImageQuant. To show that the signal generated from the FM3A cells required RT, but not due to amplification from DNA, the data from –RT reactions shown in (C) are also plotted.

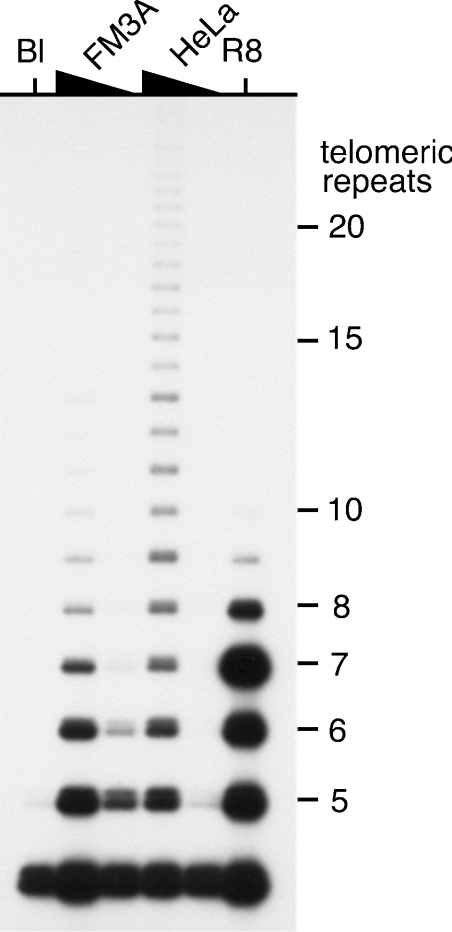

Relative activities of mouse and human telomerases in cell extracts

In order to facilitate the functional analysis of the two mTR transcripts, the telomerase activity in the FM3A and HeLa cell lysates was measured using a modified TRAP assay. In agreement with the results of Prowse et al. [19], our results (Figure 3) show that the telomerase activity from FM3A cells is much lower than that from HeLa cells. The input protein from FM3A cell lysates was 10-fold higher than HeLa cell lysates between the reactions being compared (Figure 3, lanes 2 and 4 or lanes 3 and 5). Furthermore, the telomerase from HeLa cell extracts resulted in longer products than that from FM3A cell extracts, i.e. human telomerase appeared to be more processive than mouse telomerase, also in agreement with Prowse et al. [19].

Figure 3. Mouse telomerase is less active than human telomerase.

S100 extracts from human (HeLa) and mouse (FM3A) cells were assayed for telomerase activity using a modified TRAP assay. The mouse telomerase assays used 400 or 40 ng of total protein from the cell extract per telomerase assay, and the human telomerase assays used 40 or 4 ng of total protein. Lane Bl: a negative control assay containing only buffer; lane R8: an assay with 0.05 amol of the positive control R8 oligonucleotide.

Comparison of Native/long and Native/short mTR transcripts

In order to examine how sequence and structural differences in TR can affect telomerase activity, a series of modified mTR and hTR RNA transcripts were generated (Figure 1B). All of the in vitro reconstitutions used a pET24b.mTERT construct in which the His6 tag was deleted from the C-terminus of the protein, as the presence of the tag led to suboptimal telomerase activity (results not shown). The Native/short transcript was synthesized with T7 RNA polymerase from a modified T7 RNA polymerase promoter. The transcript from this promoter did not contain any promoter-derived guanosines, thus resulting in a native mTR sequence. It has previously been demonstrated that at least two of the guanosine residues could be altered, although the resulting RNA yield is reduced [25]. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a T7 promoter has been used that contains no guanosines in the +1 to +3 region. The 5′-terminus of the transcripts, up to the terminal nucleotide, was confirmed by direct sequencing of the RNA.

Mouse telomerase was reconstituted using the Native/long and Native/short transcripts. The activity of the reconstituted telomerase containing these transcripts and the mTERT protein was measured by the TRAP assay (Figure 4). Reconstitution with Native/short transcript resulted in robust activity, whereas that with the longer (mTR Native/long) transcript led to very little or no activity. Additionally, reconstitution was tested with a Native/short transcript (Native+T7), with a 5′-extension of 4 nt (GGGC) as a consequence of transcription from the native T7 promoter, which also resulted in telomerase with very low activity.

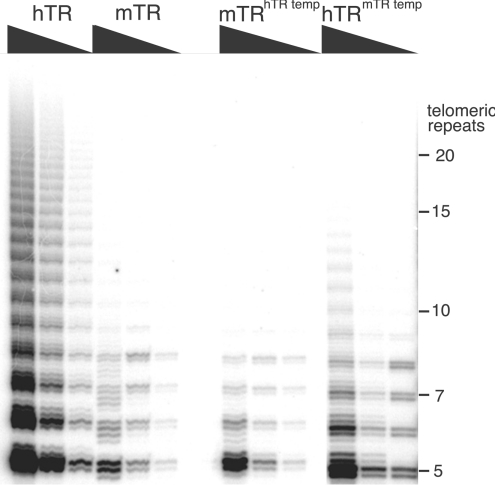

Structural features of mTR responsible for its lower activity

In order to delineate the basis for the activity differences between mTR and hTR, we constructed a set of mutant mTR transcripts that contained selected elements of the hTR transcript (Figure 1B). First, we examined the differences in the template region as the basis of lower activity of mTR. It is possible that the presence of a longer primer alignment region in the hTR is responsible for its higher level of telomerase activity. Therefore we created an mTR transcript containing three additional nucleotides in the primer alignment segment of the template region. The resulting mTR transcript (mTRhTR temp) contained a template region identical with that of hTR. The telomerase reconstituted from such a transcript was assayed using the TRAP assay and the results showed that the level of activity of the mTRhTR temp was similar to that of wild-type mTR (Figure 5). Therefore it appeared that the differences in the template region alone were not responsible for the differences in the activity of the two TRs. A reciprocal alteration in hTR, namely the reduction of the primer alignment segment by 3 nt, followed by reconstitution with mTERT, led to a significant reduction in its activity compared with the native hTR (Figure 5). This result suggests that the longer alignment segment in hTR indeed plays a role in the efficient telomere repeat synthesis by the human enzyme.

Figure 5. Influence of the length of the primer alignment region on telomerase activity.

hTR, mTR and their variants with swapped template regions (hTRmTR temp and mTRhTR temp) were reconstituted with mTERT and assayed using the TRAP assay. Each TRAP assay contained 0.2, 0.02 or 0.002 μl of the reconstitution reaction.

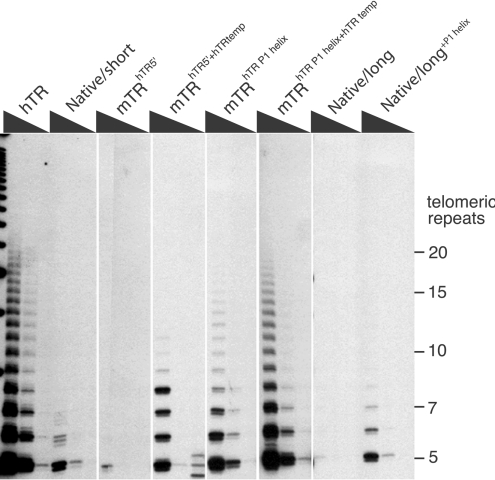

To examine the effect of the sequence upstream of the template region, we added the 43-base extension (excluding the dinucleotide immediately 5′ of the template) from hTR on to the mTR Native/short transcript, to create mTRhTR 5′. This led to a virtual abolition of activity when the telomerase enzyme was reconstituted. If, in addition to the hTR 5′-extension, the template regions were also swapped (mTRhTR 5′+hTR temp), the level of activity was increased compared with mTRhTR 5′ transcript (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Structural features of mTR responsible for the lower activity of mouse telomerase.

Telomerase was reconstituted using mTERT and hTR, mTR Native/short, mTRhTR 5′, mTRhTR 5′+hTR temp, mTRhTR P1 helix, mTRhTR P1 helix+hTR temp, mTR Native/long or mTR native long+P1 helix. TRAP assays of telomerases reconstituted were performed using 0.2, 0.02 or 0.002 μl of the reconstitution reaction.

The 5′-extension of hTR, in its native context, has the potential to form a P1 helix by base-pairing with sequences downstream of the template region. Therefore we inserted a 27-base sequence downstream of the mTR template region to facilitate the formation of a native hTR-like P1 helix in the mTR. This insertion mutant was combined with the mTRhTR 5′ construct described above, resulting in the transcript (mTRhTR P1 helix) which contains a P1 helix and a native mTR template region. When reconstituted with mTERT, this transcript dramatically increased the level of activity compared with the ‘P1-less’ mTRhTR 5′. This activity was further increased by the inclusion of the hTR template in the transcript (mTRhTR P1 helix+hTR temp). This mutant mTR, which contained the hTR template and P1 helix sequences, displayed a level of activity similar to native hTR. The increase in telomerase activity due to a longer primer-annealing segment was more striking in the presence of the hTR P1 helix than in its absence.

To further assess the importance of a putative P1 helix within the mTR transcript, the mTR Native/long transcript, which had earlier been shown to result in telomerase with very low levels of activity, was engineered to potentially form a P1 helix (Figure 6, mTR Native/long+P1 helix). This was achieved by mutating the sequence downstream of the pseudoknot so that it was complementary to the 5′-extension found in the mTR Native/long transcript (mTR Native/long+P1 helix). Although the level of activity with this mutated mTR Native/long transcript was not increased to the level seen in mTRhTR P1 helix+hTR temp, there was a clear increase in activity compared with the Native/long. These results show that irrespective of its sequence, the mere presence of a helix can contribute to some increase in activity.

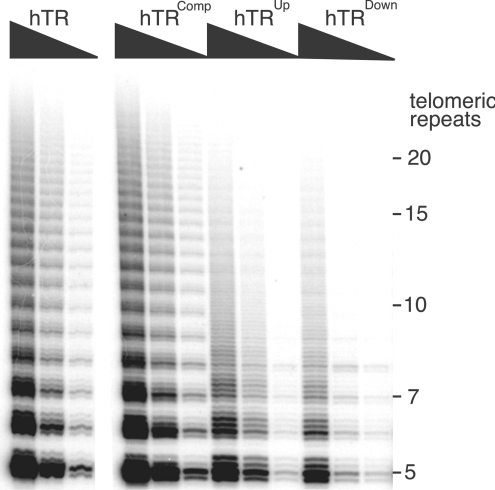

Mutating the hTR

It was of interest to determine whether the P1 helix in hTR, which is absent from mTR, was critical to its activity. First, the P1 helix of hTR was disrupted by replacing the top strand (5′ segment of the helix) or the bottom strand (3′ segment of the helix) with a non-complementary sequence and, in a separate mutant, recreating a P1 helix by combining the two mutations, which were complementary to each other. Reconstitution of the transcripts with mTERT showed that disruption of P1 helix results in reduced levels of activity compared with the wild-type hTR. The hTR transcript in which the helix was reconstructed, although of a different sequence, led to wild-type levels of activity (Figure 7). These results confirm that the presence of a helix is required for optimal telomerase activity. However, the sequence of the P1 helix appears to be not important, at least in the in vitro assays.

Figure 7. Human telomerase requires an intact P1 helix in the hTR for its optimal activity.

The telomerase activities of mTERT reconstituted with hTR, hTRComp, hTRUp or hTRDown were assayed using the TRAP assay. Each TRAP assay contained 0.2, 0.02 or 0.002 μl of the reconstitution reaction.

DISCUSSION

All vertebrate TRs described to date, except for hamster, mouse and rat, contain 5′-extensions upstream of the template sequence (ranging in length between 14 nt in the vole and 52 nt in the manatee [6]). The 5′-extension of the vertebrate TR is predicted to base-pair with a region downstream of the pseudoknot to form the P1 helix [6]. Even in TRs of ciliates such as Tetrahymena, helix I is formed by base-pairing between the sequences upstream of the template and a region downstream of the pseudoknot [26–28], with the result that the 5′-terminus of the RNA is double-stranded. Helix I has been shown to be required for optimal activity of Tetrahymena telomerase, but not required for binding of TR to TERT [29,30]. Therefore it was of interest to know the contribution of the longer 5′-extension to telomerase activity [8,10]. First, we found evidence that both long and short transcripts were present in FM3A cells. Secondly, the short transcript was much more abundant than the longer one. Furthermore, the in vitro reconstitutions of mouse telomerase with the longer transcript resulted in very low levels of activity compared with the short transcript, which was more active. The activity of the Native/short mTR transcript was dramatically reduced when four additional nucleotides were present at the 5′-terminus of mTR Native/short transcript (Figure 4), suggesting that the precise configuration of the 5′-terminus is important for mouse telomerase activity. Although it is unclear why mouse cells make two mTR transcripts, this may be a part of a mechanism evolved to regulate the level of telomerase activity.

A comparison of mouse and human telomerases shows that the mouse telomerase activity is generally low compared with human telomerase. We were interested in understanding the basis for this differential activity. It has been shown that mTR and hTR are functionally equivalent. For example, hTR can compensate for the absence of mTR in mTR−/− mice [20]. Furthermore, telomerase reconstituted using mTERT and hTR displays a high level of activity ([14] and Figure 4), similar to that obtained with hTERT reconstituted with hTR, suggesting that the determinants of this differential activity may be in the TR component. Therefore we have attempted to delineate the sequence and distinctive secondary structure features of the mTR that are responsible for a lower activity.

One of the key differences between mTR and hTR is that the primer alignment segment of the template is shorter by three bases in mTR (Figure 1). Our results show that reducing the length of this segment in hTR from 5 to 3 nt reduces the telomerase activity levels reconstituted with mTERT. It has recently been reported [31] that hTR with an mTR-like template reconstituted with hTERT leads to inactive telomerase. However, our results are in agreement with another report, which showed a reduction in activity when a similar TR mutation was reconstituted with either mTERT or hTERT [16]. This suggests that telomerase is sensitive to changes within the RNA sequence 3′ of the template and that these changes can cause different effects depending on the precise change made, reconstitution or assay conditions.

A corresponding increase in the length of the primer alignment segment in mTR from 2 to 5 nt did not increase the telomerase activity. This may be due to the extra potential base-pairs formed between the primer and the template, as a result of longer template having no influence on the telomerase activity. The extra bases allow for specificity but not necessarily stability of the TERT–TR complex. This stabilizing influence is probably afforded by the presence of a P1 helix, as shown by an increase in activity when both the P1 helix and a longer template region were added to the mTR (Figure 6).

Our results have demonstrated that the double-stranded nature of the hTR upstream region is required for optimal activity; telomerase activity was higher in an mTR containing the hTR P1 helix compared with the native mTR. Further, in the mTR engineered to contain an hTR-like P1 helix, activity was further increased by extending the mTR template to resemble the hTR template. In the absence of a P1 helix, the hTR template did not significantly increase activity of reconstituted telomerase containing mTR. The most likely explanation for this is that the double-stranded P1 helix is required to stabilize the substrate–enzyme complex after translocation. We have shown that if mTR is engineered to form a P1 helix, the resultant telomerase displays increased activity. As reported by Chen and Greider [17], when a different P1 helix was engineered into mTR, the template boundary definition of mouse telomerase was enhanced. However, it has recently been suggested that the mouse telomerase template is not well defined in the native enzyme, and that synthesis is terminated by run-off transcription [32]. This transcript is then likely nucleolytically processed, resulting in a telomeric repeat sequence. Such nucleolytic activity has been described to be associated with human telomerase [33,34].

Mutations of the portions of hTR that have the potential to base-pair and form the P1 helix caused a reduction in resultant telomerase activity if the potential P1 helix was disrupted; however, compensatory mutation, allowing the potential formation of the helix, resulted in wild-type activity. Earlier published results showed that mutations within the P1 helix of hTR reduced human telomerase activity without affecting hTERT–hTR binding [7,35], and in vivo, a mutation that disrupts the P1 helix was found to lead to a loss of telomerase activity, leading to pancytopenia, a haematological disorder [36]. Our work has shown that it is the structure (i.e. a potentially base-paired 5′-terminus) and not the sequence that is important for activity. The work presented here also shows that this increase in activity does not require hTERT as the protein component of the reconstitution. This suggests that the ability of the hTR to form a P1 helix is important for telomerase activity and that the increase in activity is an inherent feature of the RNA structure. Chemical probing of in vitro transcribed hTR was inconclusive in the P1 region, suggesting that the 5′-terminal portion of hTR may adopt several different structures in vitro [37]. However, probing of hTR extracted from cells suggested that the P1 region was indeed double-stranded [38]. Co-variation analysis of vertebrate TRs also suggested that the 5′-terminus was likely to base-pair with a complementary region downstream of the pseudoknot [6]. Our work provides direct evidence that the 5′-end of hTR must be double-stranded in order for high levels of telomerase activity to be realized.

Our results, showing that the template length of mTR contributes partly to the lower telomerase activity, are somewhat different from that in a previous report by Chen and Greider [16] addressing the same question. Chen and Greider [16] suggested that the difference between processivity of telomerase reconstituted with mTR compared with hTR was solely due to the length of the template region; extending the mTR template to resemble that of hTR resulted in hTR-like activity. There were, however, several differences in the way that the experiments were carried out. The work by Chen and Greider [16] used telomerase reconstituted with mTR supplied as two separate fragments – one fragment containing the template sequence and the pseudoknot and a second fragment containing the CR4–CR5 domain. This mTR transcript also contained a sequence at the 5′-end not present in the wild-type sequence, added as a result of transcription from a native T7 polymerase promoter. In contrast, we have used a single transcript (Native/short mTR), which possessed a 5′-terminus that closely mimics the more active, abundant mTR transcript found in murine cells. Additionally, there were important differences in the manner in which the assays were performed [6].

If the presence of a P1 helix is conserved in most vertebrate TRs, and a P1-like helix is even found in organisms as far removed as ciliates, then why is this structure absent from mTR? The organisms with TR lacking a P1 helix, namely mouse, rat and hamster, also have short telomerase template sequences, with reduced alignment domains. All other vertebrate TRs, except for the tree shrew, have alignment domains of 4 or 5 nt; these rodents have only 2 or 3 nt in their alignment domains [6]. If the P1 helix works in conjunction with an extended template, and therefore longer alignment domain, to increase telomerase processivity, then the absence of a P1 helix would reduce the conservation of sequence required to maintain the longer template; there would no longer be evolutionary pressure to maintain the longer alignment domain. This suggests that the mouse and related organisms have evolved telomerase of lower activity than the organisms with consensus TR, by loss of the conserved P1 helix. Two possibilities exist for these organisms; either an unknown associated factor compensates for the lack of a P1 helix, or some advantage is gained by having a telomerase enzyme with lower activity.

Online Data

Acknowledgments

We thank the Albert Einstein's Cancer Center DNA Sequencing Facility for automated sequencing, Mark E. Martin (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, U.S.A.) for FM3A cells and Dr Ron DePinho for the mTR and mTERT clones. This work was supported by the Public Service Research Grant to V. R. P. (AI30861).

References

- 1.Shippen-Lentz D., Blackburn E. H. Functional evidence for an RNA template in telomerase. Science. 1990;247:546–552. doi: 10.1126/science.1689074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilley D., Lee M., Blackburn E. H. Altering specific telomerase RNA template residues affects active site function. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2214–2226. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell J. R., Cheng J., Collins K. A box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-like domain at the human telomerase RNA 3′ end. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:567–576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J. L., Opperman K. K., Greider C. W. A critical stem–loop structure in the CR4–CR5 domain of mammalian telomerase RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:592–597. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachand F., Triki I., Autexier C. Human telomerase RNA–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3385–3393. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.16.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J.-L., Blasco M. A., Greider C. W. Secondary structure of vertebrate telomerase RNA. Cell. 2000;100:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bachand F., Autexier C. Functional regions of human telomerase reverse transcriptase and human telomerase RNA required for telomerase activity and RNA-protein interactions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:1888–1897. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1888-1897.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco M. A., Funk W., Villeponteau B., Greider C. W. Functional characterization and developmental regulation of mouse telomerase RNA. Science. 1995;269:1267–1270. doi: 10.1126/science.7544492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J.-Q., Hoare S. F., McFarlane R., Muir S., Parkinson E. K., Black D. M., Keith W. N. Cloning and characterization of human and mouse telomerase RNA gene promoter sequences. Oncogene. 1998;16:1345–1350. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinkley C., Blasco M. A., Funk W., Feng J., Villeponteau B., Greider C., Herr W. The mouse telomerase RNA 5′-end lies just upstream of the telomerase template sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:532–536. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng J., Funk W. D., Wang S.-S., Weinrich S. L., Avilion A. A., Chiu C.-P., Adams R. R., Chang E., Allsopp R. C., Yu J., et al. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science. 1995;269:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7544491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beattie T. L., Zhou W., Robinson M. O., Harrington L. Reconstitution of human telomerase activity in vitro. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinrich S. L., Pruzan R., Ma L., Ouellette M., Tesmer V. M., Holt S. E., Bodnar A. G., Lichsteiner S., Kim N. W., Trager J. B., et al. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg R. A., Allsopp R. C., Chin L., Morin G. B., DePinho R. A. Expression of mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase during development, differentiation and proliferation. Oncogene. 1998;16:1723–1730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins K., Gandhi L. The reverse transcriptase component of the Tetrahymena telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:8485–8490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J. L., Greider C. W. Determinants in mammalian telomerase RNA that mediate enzyme processivity and cross-species incompatibility. EMBO J. 2003;22:304–314. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen J. L., Greider C. W. Template boundary definition in mammalian telomerase. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2747–2752. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tesmer V. M., Ford L. P., Holt S. E., Frank B. C., Yi X., Aisner D. L., Ouellette M., Shay J. W., Wright W. E. Two inactive fragments of the integral RNA cooperate to assemble active telomerase with the human protein catalytic subunit (hTERT) in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:6207–6216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prowse K. R., Avilion A. A., Greider C. W. Identification of a nonprocessive telomerase activity from mouse cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:1493–1497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martín-Rivera L., Herrera E., Albar J. P., Blasco M. A. Expression of mouse telomerase catalytic subunit in embryos and adult tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:10471–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drosopoulos W. C., DiRenzo R., Prasad V. R. Human telomerase RNA template sequence is a determinant of telomere repeat extension rate. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:32801–32810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506319200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyer P. L., Hughes S. H. Site-directed mutagenic analysis of viral polymerases and related proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1996;275:538–555. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)75030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gayle R. B., III, Auger E. A., Gough G. R., Gilham P. T., Bennett G. N. Formation of MboII vectors and cassettes using asymmetric MboII linkers. Gene. 1987;54:221–228. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N. W., Wu F. Advances in quantification and characterization of telomerase activity by the telomeric repeat amplification protocol (TRAP) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2595–2597. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milligan J. F., Groebe D. R., Witherell G. W., Uhlenbeck O. C. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero D. P., Blackburn E. H. A conserved secondary structure for telomerase RNA. Cell. 1991;67:343–353. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormick-Graham M., Romero D. P. Ciliate telomerase structural features. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1091–1097. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.7.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperger J. M., Cech T. R. A stem–loop of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA distant from the template potentiates RNA folding and telomerase activity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7005–7016. doi: 10.1021/bi0103359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai C. K., Miller M. C., Collins K. Roles for RNA in telomerase nucleotide and repeat addition processivity. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1673–1683. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason D. X., Goneska E., Greider C. W. Stem–loop IV of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA stimulates processivity in trans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5606–5613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5606-5613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gavory G., Farrow M., Balasubramanian S. Minimum length requirement of the alignment domain of human telomerase RNA to sustain catalytic activity in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4470–4480. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J., Ly H., Hussain A., Abraham M., Pearl S., Tzfati Y., Parslow T. G., Blackburn E. H. A universal telomerase RNA core structure includes structured motifs required for binding the telomerase reverse transcriptase protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:14713–14718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405879101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huard S., Autexier C. Human telomerase catalyzes nucleolytic primer cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2171–2180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oulton R., Harrington L. A human telomerase-associated nuclease. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:3244–3256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ly H., Blackburn E. H., Parslow T. G. Comprehensive structure-function analysis of the core domain of human telomerase RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:6849–6856. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6849-6856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ly H., Calado R. T., Allard P., Baerlocher G. M., Lansdorp P. M., Young N. S., Parslow T. G. Functional characterization of telomerase RNA variants found in patients with hematologic disorders. Blood. 2005;105:2332–2339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blasco M. A., Lee H.-W., Hande M., Samper E., Lansdorp P., DePinho R. A., Greider C. Telomere shortening and tumour formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell. 1997;91:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antal M., Boros E., Solymosy F., Kiss T. Analysis of the structure of human telomerase RNA in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:912–920. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.