Abstract

The immunodominant region of the human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), the antibody-binding site of glycoprotein K8.1A, was mapped to the N-terminal region by using overlapping peptides and a residue replacement method. The main epitope was located within residues 44 to 56 (GQVYQDWL----C). Based on this information, we developed an enzyme immunoassay to detect HHV-8 antibodies in human sera using a four-branch multiple antigenic peptide as the antigen. The sensitivity and specificity of the assay were 96 and 99.4%, respectively. This assay should be useful for population-based, epidemiological studies of HHV-8 infection.

Molecular and epidemiological studies have linked the newly identified gamma herpesvirus human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) to Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), body-cavity-based lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman's disease (2, 5, 8, 20, 24). However, the true prevalence of HHV-8 infection in the general population has yet to be determined because there is no “gold standard” diagnostic method. For example, the reported seroprevalence in studies of healthy U.S. blood donors ranged from 0 to 29%, depending on the assay used (1, 6, 11, 19, 22).

Although HHV-8 DNA has been detected in >95% of KS lesions by PCR (2, 5, 12), only approximately 50% of KS patients have detectable viral DNA in their blood (25). Therefore, the utility of PCR for detecting HHV-8 infection is limited. On the other hand, HHV-8 antibodies in patient serum or plasma were consistently detected by several serological methods, including immunoblotting, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), and immunofluorescence assay with a variety of antigen preparations, such as whole viral lysates, recombinant proteins, and synthetic peptides (7, 10, 11, 13, 16, 19, 21, 23, 25). However, in a recent evaluation of assay performance, no single assay was 100% sensitive and specific, and there was frequent disagreement for individual samples, especially in asymptomatic populations (9, 22, 25).

As part of our efforts to develop high-throughput assays for epidemiological studies, we fine mapped the antibody-binding site of glycoprotein K8.1 (gpK8.1A), one of the most antigenic HHV-8 gene products (4, 15, 18), and developed a highly sensitive and specific assay for HHV-8 antibodies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthetic peptides.

Peptides were synthesized according to the manufacturer's protocol with an automatic synthesizer (model 432A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), partially purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.), lyophilized, and stored desiccated at room temperature until use.

For the initial epitope mapping, we used 12 20- to 22-mer overlapping peptides encompassing residues 25 to 197 of gpK8.1A (3) (Table 1). To determine the critical amino acids required for antibody binding, peptide analogs that differed from the wild-type antigenic peptide by one amino acid at a time were synthesized (Table 2). To evaluate the analytical sensitivity of the assay, additional peptides that extended systematically toward the N terminus or the C terminus of the antigenic peptide were used (Table 3). Finally, a four-branch multiple antigenic peptide (MAP) (26) was developed for assay evaluation.

TABLE 1.

Overlapping peptides used for mapping the immunodominant region of gpK8.1A

| Peptide | Residues | Length (mer) |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 25-44 | 20 |

| P2 | 39-58 | 20 |

| P3 | 54-73 | 20 |

| P4 | 69-88 | 20 |

| P5 | 83-104 | 22 |

| P6 | 99-120 | 22 |

| P7 | 115-134 | 20 |

| P8 | 129-148 | 20 |

| P9 | 142-161 | 20 |

| P10 | 154-173 | 20 |

| P11 | 166-185 | 20 |

| P12 | 178-197 | 20 |

TABLE 2.

P2 peptide analogs used for determining the critical amino acids required for antibody bindinga

| Peptide analog | Sequence |

|---|---|

| P2 (wild type) | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.1 | QEVWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.2 | QEGGSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.3 | QEGWGGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.4 | QEGWSVQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.5 | QEGWSGGVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.6 | QEGWSGQGYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.7 | QEGWSGQVGQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.8 | QEGWSGQVYGDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.9 | QEGWSGQVYQGWLGRMNCSY |

| P2.10 | QEGWSGQVYQDGLGRMNCSY |

| P2.11 | QEGWSGQVYQDWGGRMNCSY |

| P2.12 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLVRMNCSY |

| P2.13 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGGMNCSY |

| P2.14 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRGNCSY |

| P2.15 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMGCSY |

| P2.16 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNGSY |

| P2.17 | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCGY |

Amino acid substitutions are indicated in boldface print. Residues comprising the main epitope are underlined.

TABLE 3.

P2 peptide analogs used for identifying the boundaries of the antigenic domain

| Peptide analog | Sequence |

|---|---|

| P2 (wild type) | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2+7N | RSHLGFWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2+6N | SHLGFWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2+4N | LGFWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2+2N | FWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY |

| P2+2C | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSYEN |

| P2+6C | QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSYENMTAL |

The one-letter amino acid symbols recommended by the IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature are used throughout this report (14).

PEIA.

Published procedures for the peptide EIA (PEIA), with slight modifications, were followed (21). Briefly, peptides were dissolved in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.4) (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.) to a final concentration of 5 μg/ml (2.5 μg/ml for MAP), and 110 μl of this solution was used to coat microtiter wells by overnight incubation at 4°C. Peptide-coated wells were washed twice with pH 7.4 phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Triton X-100, air dried, and stored desiccated at −20°C until use. Nonspecific binding sites of the peptide-coated wells were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (milk buffer) for 30 min at 37°C just prior to assaying. Sera were diluted 1:100 (initial screening) or 1:150 (final MAP assay) in milk buffer and allowed to react with the peptide-coated wells for 1 h at 37°C. Bound antibodies were detected with goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (heavy and light chains)-peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) and tetramethylbenzidine and hydrogen peroxide substrates (BioFX, Owings, Md.) after the plate was washed five times with PBS-0.05% Triton X-100. The baseline-corrected optical density (the optical density at 450 nm is the A450 minus the A630) was measured. The mean optical density at 450 nm of the 20 normal controls (i.e., KS-negative and human immunodeficiency virus-negative specimens) plus 5 standard deviations was chosen as the assay cutoff.

Human sera.

Sera from KS patients (n = 81) and normal controls (n = 165) were obtained from prior studies conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of the 81 KS patients, 79 were human immunodeficiency virus positive, while the normal controls were healthy blood donors. Specimens were tested for HHV-8 antibodies by a mouse monoclonal antibody-enhanced immunofluorescence assay (mIFA) as described previously (19, 21). All 81 KS-positive specimens were mIFA positive, while the 165 normal control specimens were mIFA negative. Three serum pools (four specimens each) derived from 12 of the 81 KS-positive sera were used for initial epitope mapping.

RESULTS

Mapping of the immunodominant region of gpK8.1A.

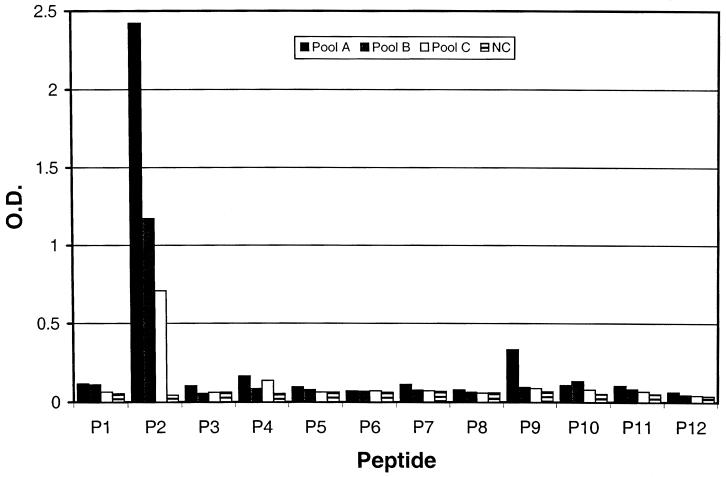

The serum reactivities of the 12 overlapping K8.1 peptides with three KS-positive serum pools and with a normal control specimen are shown in Fig. 1. Peptide P2 (residues 39 to 58; QEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSY) was the only peptide recognized by all three KS-positive serum pools, while none of the peptides reacted with the normal control specimen (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Serum reactivities of 12 overlapping peptides (Table 1) derived from HHV-8 gpK8.1A. Pools A, B, and C are serum pools containing four different randomly chosen specimens from 81 KS patients. NC is a normal control serum from a healthy blood donor. O.D., optical density.

Fine mapping of the P2 epitope.

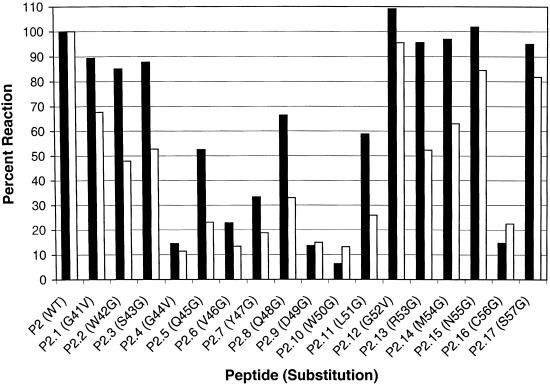

Figure 2 depicts the seroreactivity profiles of two KS-positive specimens with P2 and its replacement analogs listed in Table 2. From these data, we determined that the most critical amino acids for antibody binding were within a linear region from residue 44 (G) to residue 51 (L) and residue 56 (C) of gpK8.1A, since the peptide analogs (P2.4 to P2.11 and P2.16) with substitutions at those positions were on average less than 50% as reactive as wild-type peptide P2.

FIG. 2.

Results of fine epitope mapping by the amino acid replacement method. Peptide sequences are listed in Table 2. Amino acid substitutions are indicated on the x axis. The serum reactivity of each peptide is compared to that of the wild-type (WT) peptide (P2). Black and white bars represent two different KS-positive specimens tested in this assay.

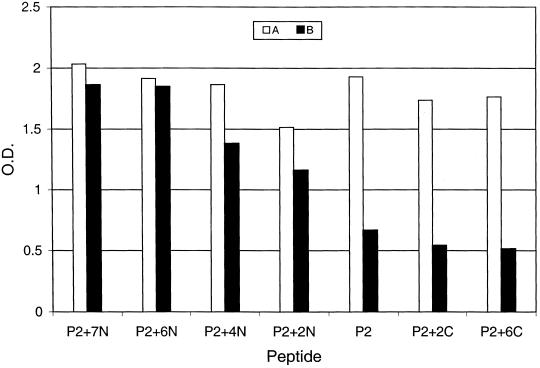

Sensitivity of the linear PEIA.

Preliminary tests showed that P2 detected only 14 of 20 KS-positive specimens (70%), while a 31-residue peptide (PK8.1; RSHLGFWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSYENMT) containing the sequence of P2 (underlined) detected 26 of 30 KS-positive specimens (87%) (25). To investigate which additional amino acids were responsible for the improved assay sensitivity, six additional P2 analogs were synthesized with extensions of different lengths at either the N or the C terminus (Table 3). Figure 3 shows the typical reactivity profiles. Sample A, a highly reactive specimen, reacted equally well with P2 and all of the longer analogs. Sample B, a specimen weakly reactive with P2, showed a gradual increase in reactivity when the peptides were extended toward the N terminus and reached a reactivity level similar to that of sample A after six residues (SHLGFW) were added. However, no change in reactivity was observed when the peptides were extended toward the C terminus.

FIG. 3.

Extending the sequence of P2 toward the N terminus increases the analytical sensitivity with some sera. Serum A is a highly reactive specimen, while serum B is a weakly reactive specimen. O.D., optical density.

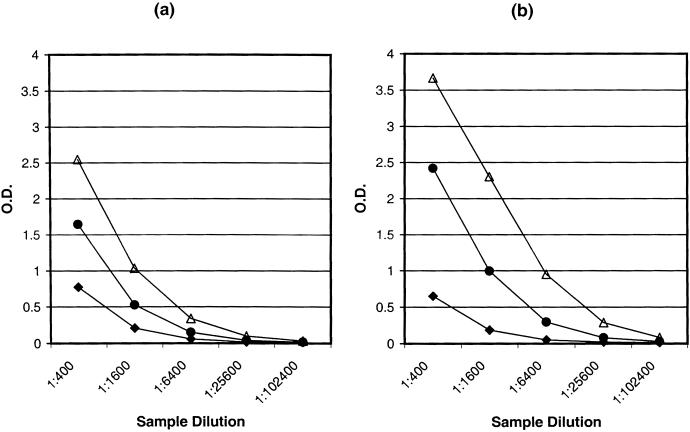

Sensitivity of the PK8.1-MAP EIA.

To further improve the assay sensitivity, we synthesized and evaluated a MAP (PK8.1-MAP) with four branches of the most sensitive extended sequence described above (RSHLGFWQEGWSGQVYQDWLGRMNCSYENX). A diaminopropionic acid residue (Advanced Chemtech, Louisville, Ky.), as indicated by an “X,” was incorporated to improve the solubility of the MAP. This branched peptide showed an eightfold increase in analytical sensitivity over peptide P2 (i.e., an increase in sample dilution) and a twofold increase over peptide PK8.1 (Fig. 4). To evaluate the clinical sensitivity and specificity of the PK8.1-MAP EIA, we tested the 81 mIFA-positive specimens from KS patients and the 165 mIFA-negative specimens from healthy blood donors. Of the 81 KS-positive specimens, 78 (96%) were positive, while only 1 (0.6%) of the 165 normal control specimens was repeatedly positive, with a signal-to-cutoff ratio of 1.3. The average signal-to-cutoff ratio for the 78 positive specimens was over 20.

FIG. 4.

Typical serum reactivities of peptides PK8.1-MAP (▵), PK8.1 (•), and P2 (⧫) with two (a and b) KS-positive specimens. O.D., optical density.

DISCUSSION

HHV-8 glycoprotein K8.1, derived from a spliced transcript of open reading frame K8.1, is one of the most antigenic HHV-8 gene products (3). This characteristic, along with its lack of homology in other herpesviruses, makes it a prime candidate for the development of sensitive and specific serological assays for HHV-8 antibodies.

To develop a peptide-based immunoassay, we first identified the immunodominant region of gpK8.1A. Initial screening of overlapping peptides with pooled KS-positive sera determined that a dominant epitope resides within residues 39 to 58 of K8.1 (P2), in agreement with previous reports that the dominant antigenic domain is located at the N-terminal region of K8.1 (17, 18). It was previously reported that a 31-residue peptide containing the sequence of P2 was useful for detecting HHV-8 antibodies in human sera or plasma (25). Further analysis by the amino acid replacement method revealed the presence of multiple discontinuous epitopes within residues 32 to 58, with the main epitope being GQVYQDWL----C (residues 44 to 56). This information was used to develop a more sensitive assay, PK8.1-MAP EIA, for HHV-8 antibody detection.

MAPs have been widely used as immunogens for antibody production because of their enhanced immunogenicity over linear peptides without the need for conjugation to a carrier protein. This study shows that a MAP is also more strongly immunoreactive than the corresponding linear peptide, possibly due to enhanced binding to the solid phase. Such antigens should prove very useful in diagnostic applications for detecting viral or bacterial infections.

We used mIFA as our gold standard method to select specimens for sensitivity and specificity evaluation. mIFA is known to be the most sensitive assay available today for HHV-8 antibody detection. However, its specificity is yet to be determined. Nevertheless, when mIFA results were used as a gold standard, the PK8.1-MAP EIA was found 96% sensitive for a KS population. The performance of the assay for non-KS populations has not yet been evaluated.

Glycoproteins derived from the HHV-8 K8.1 gene are known to be highly antigenic and may be useful for detecting HHV-8 infections. The use of a recombinant K8.1-glutathione S-transferase fusion protein as an antigen has been described in several studies. Zhu and colleagues (27) described an immunoblot assay that detected 93% of KS-positive specimens, while Katano and coworkers (15) reported an EIA that detected only 52% of KS-positive specimens. The lower sensitivity of the assay of Katano et al. (15) was thought to be due to the lack of glycosylation of the antigen (expressed in bacteria) compared to the method of Zhu et al. (27), who used a glycosylated antigen (expressed in eukaryotic cells). Glycosylated K8.1 has been found to be more immunoreactive than nonglycosylated K8.1 (13). However, the PK8.1-MAP EIA described in this report is as sensitive as if not more sensitive than the assay used by Zhu et al. (27), indicating that a lack of glycosylation may not be the only cause of lower sensitivity. Another difference between the two reported antigens was that the GST fusion domain of the construct used by Katano et al. (15) was at the N terminus of K8.1, while that in the study of Zhu et al. (27) was at the C terminus. Since the immunodominant region of K8.1 is located at the N terminus, it may be partially blocked by the bulky glutathione S-transferase fusion domain (26 kDa).

Recently, Inoue and coworkers (13) described an IFA with recombinant Semliki Forest viruses expressing gpK8.1A in BHK-21 cells as the antigen (K8.1-IFA); this assay was as sensitive as the mIFA. Although our PK8.1-MAP EIA is slightly less sensitive than either the mIFA or the K8.1-IFA, it should perform adequately in large-scale epidemiological investigations that require high throughput, ease of operation, and high specificity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablashi, D., L. Chatlynne, H. Cooper, D. Thomas, M. Yadav, A. W. Norhanom, A. K. Chandana, V. Churdboonchart, S. A. Kulpradist, M. Patnaik, K. Liegmann, R. Masood, M. Reitz, F. Cleghorn, A. Manns, P. H. Levine, C. Rabkin, R. Biggar, F. Jensen, P. Gill, N. Jack, J. Edwards, J. Whitman, and C. Boshoff. 1999. Seroprevalence of human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) in countries of Southeast Asia compared to the USA, the Caribbean and Africa. Br. J. Cancer 81:893-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cesarman, E., Y. Chang, P. S. Moore, J. W. Said, and D. M. Knowles. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1186-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandran, B., C. Bloomer, S. R. Chan, L. Zhu, E. Goldstein, and R. Horvat. 1998. Human herpesvirus-8 ORF K8.1 gene encodes immunogenic glycoproteins generated by spliced transcripts. Virology 249:140-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandran, B., M. S. Smith, D. M. Koelle, L. Corey, R. Horvat, and E. Goldstein. 1998. Reactivities of human sera with human herpesvirus-8-infected BCBL-1 cells and identification of HHV-8-specific proteins and glycoproteins and the encoding cDNAs. Virology 243:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, Y., E. Cesarman, M. S. Pessin, F. Lee, J. Culpepper, D. M. Knowles, and P. S. Moore. 1994. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science 266:1865-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatlynne, L. G., and D. V. Ablashi. 1999. Seroepidemiology of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Semin. Cancer Biol. 9:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, D. A., R. W. Humphrey, F. M. Newcomb, T. R. O'Brien, J. J. Goedert, S. E. Straus, and R. Yarchoan. 1997. Detection of serum antibodies to a Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific peptide. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1071-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupin, N., M. Grandadam, V. Calvez, I. Gorin, J. T. Aubin, S. Havard, F. Lamy, M. Leibowitch, J. M. Huraux, J. P. Escande, and H. Agut. 1995. Herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in patients with Mediterranean Kaposi's sarcoma. Lancet 345:761-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engels, E. A., D. Whitby, P. B. Goebel, A. Stossel, D. Waters, A. Pintus, L. Contu, R. J. Biggar, and J. J. Goedert. 2000. Identifying human herpesvirus 8 infection: performance characteristics of serologic assays. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:346-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao, S. J., L. Kingsley, D. R. Hoover, T. J. Spira, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, P. Parry, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao, S. J., L. Kingsley, M. Li, W. Zheng, C. Parravicini, J. Ziegler, R. Newton, C. R. Rinaldo, A. Saah, J. Phair, R. Detels, Y. Chang, and P. S. Moore. 1996. KSHV antibodies among Americans, Italians and Ugandans with and without Kaposi's sarcoma. Nat. Med. 2:925-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang, Y. Q., J. J. Li, M. H. Kaplan, B. Poiesz, E. Katabira, W. C. Zhang, D. Feiner, and A. E. Friedman-Kien. 1995. Human herpesvirus-like nucleic acid in various forms of Kaposi's sarcoma. Lancet 345:759-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue, N., E. C. Mar, S. C. Dollard, C. P. Pau, Q. Zheng, and P. E. Pellett. 2000. New immunofluorescence assays for detection of human herpesvirus 8-specific antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 7:427-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). 1984. Nomenclature and symbolism for amino acids and peptides, recommendations 1983. Eur. J. Biochem. 138:9-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katano, H., T. Iwasaki, N. Baba, M. Terai, S. Mori, A. Iwamoto, T. Kurata, and T. Sata. 2000. Identification of antigenic proteins encoded by human herpesvirus 8 and seroprevalence in the general population and among patients with and without Kaposi's sarcoma. J. Virol. 74:3478-3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kedes, D. H., D. Ganem, N. Ameli, P. Bacchetti, and R. Greenblatt. 1997. The prevalence of serum antibody to human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus) among HIV-seropositive and high-risk HIV-seronegative women. JAMA 277:478-481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang, D., A. Birkmann, F. Neipel, W. Hinderer, M. Rothe, M. Ernst, and H. H. Sonneborn. 2000. Generation of monoclonal antibodies directed against the immunogenic glycoprotein K8.1 of human herpesvirus 8. Hybridoma 19:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang, D., W. Hinderer, M. Rothe, H. H. Sonneborn, F. Neipel, M. Raab, H. Rabenau, B. Masquelier, and H. Fleury. 1999. Comparison of the immunoglobulin-G-specific seroreactivity of different recombinant antigens of the human herpesvirus 8. Virology 260:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lennette, E. T., D. J. Blackbourn, and J. A. Levy. 1996. Antibodies to human herpesvirus type 8 in the general population and in Kaposi's sarcoma patients. Lancet 348:858-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore, P. S., and Y. Chang. 1995. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi's sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:1181-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pau, C. P., L. L. Lam, T. J. Spira, J. B. Black, J. A. Stewart, P. E. Pellett, and R. A. Respess. 1998. Mapping and serodiagnostic application of a dominant epitope within the human herpesvirus 8 ORF 65-encoded protein. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1574-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabkin, C. S., T. F. Schulz, D. Whitby, E. T. Lennette, L. I. Magpantay, L. Chatlynne, and R. J. Biggar. 1998. Interassay correlation of human herpesvirus 8 serologic tests. HHV-8 Interlaboratory Collaborative Group. J. Infect. Dis. 178:304-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson, G. R., T. F. Schulz, D. Whitby, P. M. Cook, C. Boshoff, L. Rainbow, M. R. Howard, S. J. Gao, R. A. Bohenzky, P. Simmonds, C. Lee, A. de Ruiter, A. Hatzakis, R. S. Tedder, I. V. Weller, R. A. Weiss, and P. S. Moore. 1996. Prevalence of Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus infection measured by antibodies to recombinant capsid protein and latent immunofluorescence antigen. Lancet 348:1133-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soulier, J., L. Grollet, E. Oksenhendler, P. Cacoub, D. Cazals-Hatem, P. Babinet, M. F. d'Agay, J. P. Clauvel, M. Raphael, L. Degos, and F. Sigaux. 1995. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood 86:1276-1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spira, T. J., L. Lam, S. C. Dollard, Y. X. Meng, C. P. Pau, J. B. Black, D. Burns, B. Cooper, M. Hamid, J. Huong, K. Kite-Powell, and P. E. Pellett. 2000. Comparison of serologic assays and PCR for diagnosis of human herpesvirus 8 infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2174-2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tam, J. P. 1988. Synthetic peptide vaccine design: synthesis and properties of a high-density multiple antigenic peptide system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:5409-5413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu, L., R. Wang, A. Sweat, E. Goldstein, R. Horvat, and B. Chandran. 1999. Comparison of human sera reactivities in immunoblots with recombinant human herpesvirus (HHV) -8 proteins associated with the latent (ORF73) and lytic (ORFs 65, K8.1A, and K8.1B) replicative cycles and in immunofluorescence assays with HHV-8-infected BCBL-1 cells. Virology 256:381-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]