Abstract

The antigenic potential of decorin binding protein A (DbpA) was evaluated in serodiagnosis of human Lyme borreliosis (LB). The dbpA was cloned and sequenced from the three pathogenic Borrelia species common in Europe. Sequence analysis revealed high interspecies heterogeneity. The identity of the predicted amino acid sequences was 43 to 62% among Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii. The respective recombinant DbpAs (rDbpAs) were produced and tested as antigens by Western blotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). One hundred percent of patients with neuroborreliosis (NB) and 93% of patients with Lyme arthritis (LA) reacted positively. Sera from the majority of patients reacted with one rDbpA only and had no or low cross-reactivity to other two variant proteins. In patients with culture-positive erythema migrans (EM), the sensitivity of rDbpA immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM ELISA was low. The DbpA seems to be a sensitive and specific antigen for the serodiagnosis of LA or NB, but not of EM, provided that variants from all three pathogenic borrelial species are included in the combined set of antigens.

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is a multiorgan infection caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. A subspecies, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, causes human LB infections in the United States (38). In Europe, however, three different borrelial subspecies, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii, are known etiologic agents of LB (1).

The diagnosis of LB is clinical, but laboratory tests, culture, PCR, and serologic assays (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and Western blotting [WB]), are frequently needed to confirm the diagnosis. Culturing B. burgdorferi from clinical samples other than erythema migrans lesions is difficult (43), and the PCR-based methods seem to be too insensitive for routine laboratory testing for LB (29, 37), probably because of the scarcity of bacteria in clinical samples (39). The mainstay of laboratory diagnosis for LB has been serologic assays of antibodies against B. burgdorferi, although their performance in different laboratories is highly variable (5). ELISA has been widely used as a screening test. In Europe, however, these assays using whole-cell lysates (WCL) or flagellin as antigens are not standardized, which limits their sensitivity and specificity (11). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States suggested a two-test approach in which unequivocal results in the ELISA are confirmed by WB. In Europe especially, the clinical implications of this recommended strategy have remained unclear (3, 20, 34). WB does not seem to discriminate between true- and false-positive test results or between active and previous B. burgdorferi infections (11). One factor causing difficulties in serologic tests is the existence of three different pathogenic species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato causing LB in Europe (23, 24). Among individual borrelial proteins from different species, sequence heterogeneity varies up to 40% (8, 21, 33, 35), and their use as antigens may affect the sensitivity of the assays (18-20).

In hopes of increasing the specificity of serodiagnosis, a number of borrelial recombinant proteins have been tested (an 83-kDa protein, flagellin, OspA, OspB, OspC, OspE, OspF, p22, BBK32, VlsE, and P39) (10, 17, 25-28, 31, 32, 35). So far, none of them has proved superior to the current routine serology.

Decorin binding protein A (DbpA), a borrelial outer surface protein, is one of the key proteins in B. burgdorferi. DbpA elicits a strong antibody response during experimental murine borreliosis and has been suggested as a potential vaccine protein (6, 9, 14, 15). DbpA has not, however, been tested in the serodiagnosis of human LB.

We therefore tested DbpA in the serodiagnosis of LB. dbpA was cloned and sequenced from the three European pathogenic borrelial species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii and B. garinii. The respective recombinant DbpAs (rDbpA) were thereafter evaluated as antigens in WB and in ELISA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Finnish borrelial strains were received from Matti Viljanen (National Public Health Institute, Turku, Finland). B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA was isolated from cerebrospinal fluid of a Finnish patient with neuroborreliosis (NB), and B. afzelii A91 and B. garinii 40 were isolated from skin biopsy samples of Finnish patients with LB. B. afzelii A91 and B. garinii 40 are low-passage strains, and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA is a high-passage strain. The strains were genotyped by PCR and sequencing, the target DNA being a fragment from the flagellin gene of B. burgdorferi (24). B. afzelii strain SK1 was used in our in-house ELISA to detect antibodies against borrelial WCL proteins. Borrelia cells were cultivated in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK-H) medium (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 33°C in 5% CO2. The Escherichia coli host cell strains used for cloning and expression of recombinant proteins were INFαF (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) and M15 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), respectively.

DNA purification.

Borrelial genomic DNA was purified with a Dneasy tissue kit (Qiagen). Purified DNA was used in PCR and cloning experiments. Plasmid DNA was purified with a QIAprep-spin plasmid kit (Qiagen).

PCR and DNA sequencing.

A PCR-based approach was employed to amplify and sequence the dbpA alleles from three different isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii A91, and B. garinii 40. Primers for dbpA PCR amplification were designed on the basis of published dbpA sequences (Table 1). Several primer pairs were designed and tested to ensure that the entire coding sequence of the dbpA was obtained. To eliminate any errors possibly made by Taq polymerase, the two strands of each dbpA were sequenced independently at least twice. Expression primers for each strain encoding the mature portion of the DbpA protein after cysteine at the site of posttranslational acylation were chosen from the analyzed sequences. Approximately 1 ng of template DNA was used under standard PCR conditions: 30 cycles of 94°C denaturing for 1 min, 50°C annealing for 1 min, and 72°C extension for 1 min 30 s with AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). The PCR amplified full-length or partial dbpA was cloned to the pCR 2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) for sequencing. DNA sequencing was performed at the Core Facility of the Haartman Institute, University of Helsinki, with a DyePrimer (T7, M13Rev) cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.). Sequencing reactions were run and analyzed by the automated sequencing apparatus model 373A (Applied Biosystems Inc.). DNA and protein sequences were analyzed with Lasergene software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR amplification of dbpA

| No. | Primera | Location | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. burgdorferi sensu stricto | |||

| 1 | 5"-ATA TTG AAA ATG GTG GAG AG-3" | −172-−153 | B31 (AF069269) |

| 2 | 5"-CCG GAT CCG GAC TAA CAG GAG CAA CAA AAA TAA G-3" | 76-95 | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA (AF441834) |

| 3 | 5"-CAG ATG GAT TTG GTT GGG TAT TGT TTT TA-3" | 628-600 | B31 |

| 4 | 5"-CCG GTA CCC AGA TGG ATT TGG TTG GGT ATT GTT-3" | 628-604 | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA |

| B. garinii | |||

| 5 | 5"-GTC AAT TCT TGG CTA TGT TTG-3" | −356-−336 | Ip90 (AF069258) |

| 6 | 5"-TAA ACA CAG CTG AAA GAT TG-3" | −245-−226 | Ip90 |

| 7 | 5"-GTT AGC CTG TTA GTA GCA TG-3" | 46-65 | B. garinii 40 (AF441832) |

| 8 | 5"-CCG GAT CCG GCT TAA CAG GAG AAA CTA-3" | 67-85 | B. garinii 40 |

| 9 | 5"-CAT GCT ACT AAC AGG CTA AC-3" | 65-46 | B. garinii 40 |

| 10 | 5"-ACT GTT CCT GTC ATT TTT TG-3" | 407-388 | Ip90 |

| 11 | 5"-CCG GTA CCT TAT GTA GTA GCA GCA GTG-3" | 561-543 | B. garinii 40 |

| 12 | 5"-ATA AAA ATG TTG TTT ATT ATG TAG-3" | 578-554 | Ip90 |

| B. afzelii | |||

| 13 | 5"-ATG ATT AAA TAT AAT AAA ATT ATA C-3" | 1-25 | BO23 (AF069267) |

| 14 | 5"-CTA GCC TGT TAG CAG CAT GT-3" | 44-63 | BO23 |

| 15 | 5"-TGT AGT TTA ACA GGA AAA GC-3" | 61-80 | BO23 |

| 16 | 5"-CCG GAT CCA GTT TAA CAG GAA AAG CTA G-3" | 64-83 | B. afzelii A91 (AF441833) |

| 17 | 5"-GCA ACA GAA GAG GAA ACT AT-3" | 199-218 | B. afzelii A91 |

| 18 | 5"-ATA GTT TCC TCT TCT GTT GC-3" | 218-199 | B. afzelii A91 |

| 19 | 5"-TTA TTT TTG ATT TTT AGT TTG TT-3" | 513-491 | B023 |

| 20 | 5"-CCG GTA CCT TAT TTT TGA TTT TTA GTT TGT T-3" | 513-491 | B. afzelii A91 |

| 21 | 5"-ATA AAA ATG TTG TTT ATT TTT G-3" | 529-505 | BO23, B31b |

Restriction enzyme sites of BamHI and KpnI in expression primers are underlined.

3" end from BO23.

Cloning and expression of DbpA.

For expression of recombinant DbpA (rDbpA), six-His-tagged protein constructs were generated. The forward and reverse primers included a BamHI site and a KpnI site, respectively. The PCR-amplified DNA encoding the mature portion of DbpA was cloned into pCR 2.1-TOPO plasmid (Invitrogen). The recombinant plasmid was purified and digested with BamHI and KpnI restriction enzymes. The cleaved dbpA was then ligated to a similarly digested pQE-30 expression plasmid (Qiagen) and transformed into E. coli M15 host cells. The transformation mixture was plated onto Luria-Bertani plates containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. A primary culture for expression of the DbpA construct was started by inoculating a single colony from a fresh transformant plate into 50 ml of Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. The culture was incubated at 37°C with shaking overnight. After 1:50 dilution, 1,500 ml of Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml was incubated at 37°C for 3 h (until growth reached the mid-log phase; the optical density at 600 nm [OD600] was ca. 0.6). Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside was added to a final concentration of 0.7 mM, and the mixture was incubated for a further 3 h. The cells were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm in a superspeed centrifuge, Sorvall RC-5B Plus; DuPont Company, Wilmington, Del.) for 10 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and sonicated in PBS with a Soniprep 150 sonicator (Sanyo, Japan) for 5 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm. The sonicate supernatant containing the rDbpA protein was applied to a Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow column (Pharmacia, Sweden) containing Ni2+ ions. rDbpA was eluted from the column by increasing the amount of imidazole. The expression and purity of the rDbpA was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Immunoblotting.

rDbpAs originating from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA, B. afzelii A91, or B. garinii 40 (referred to here as rDbpABbia, rDbpABaA91, and rDbpABg40, respectively) were fractionated in SDS-PAGE (12.5% polyacrylamide) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad; 0.2-μm pore size) by semidry transfer with 40 mM glycine-50 mM Tris (pH 9.0)-0.375% (wt/vol) SDS-20% (vol/vol) methanol buffer. Twelve micrograms of each rDbpA was used for one 7-cm-wide nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membranes were cut to approximately 2-mm strips which were soaked in 0.1% Tween 20-0.9% NaCl. Serum samples were diluted in 0.1% Tween 20, 0.9% NaCl, 0.1 g of fat-free bovine milk powder per liter (Valio, Helsinki, Finland). Samples were incubated at a 1:100 dilution for 2 h. After four buffer rinses for a total of 20 min, the blots were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.) at 1:5,000 for 2 h. The secondary antibody for immunoblots with plasma from mice infected with B. garinii was alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Orion, Espoo, Finland). After washing, the bands were visualized with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitro blue tetrazolium (Sigma Chemical Co.). The reaction was terminated 10 to 15 min later by washing with distilled water.

ELISA.

For ELISAs measuring anti-DbpA antibodies, the wells in a microtiter plate were coated with 100 μl (2 μg/ml) of variant recombinant DbpA proteins overnight. After washing, 100 μl of diluted serum samples was added to the wells, and these mixtures were incubated overnight. Serum samples were diluted 1:100 or 1:10 in 5 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per ml in 155 mM NaCl-0.04% Tween 20 buffer. The 1:10 dilution was used with serum samples from erythema migrans (EM) patients. After being washed, the wells were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG or IgM (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Inc.) at 1:5,000 in BSA-NaCl-Tween for 2 h. The reactions were visualized with 4-nitrophenylphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) at 1 mg/ml in diethanolamine buffer pH 10.0. The OD measurements were done after 15 to 30 min at a wavelength of 405 nm with a Multiscan photometer (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland).

Samples.

For WB, human serum samples were collected from well-defined, clinically typical LB patients (10 with neuroborreliosis [NB], and 10 with Lyme arthritis [LA]). Clinical diagnosis of all patients was confirmed in ELISA by demonstrating antibodies in serum against WCL from B. afzelii strain SK1 (in-house ELISA) and flagella (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), as described earlier (36). Serum samples from five patients with syphilis, five rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive serum samples, five Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) IgM-positive serum samples, and five serum samples from healthy blood donors were used as controls.

For ELISA analyses, we collected human serum samples from 14 patients with NB, 15 patients with LA, and 23 patients with culture- or PCR-positive EM (B. afzelii, n = 17; B. garinii, n = 4, and genotyping not feasible, n = 2). In patients with NB and LA, the diagnosis was confirmed serologically, as in samples for WB. From the EM patients, serum samples were taken at diagnosis and 1 to 3 months posttreatment. Serum samples from patients with syphilis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), RF positivity, antistreptolysin (ASO) positivity, or EBV infection and from healthy blood donors were used as controls.

Plasma samples from mice infected with B. garinii strain Å218 were obtained from Matti Viljanen (National Public Health Institute, Turku, Finland). The infection was verified by culturing ear pinnae from each mouse at each time point when groups of five mice were sacrificed. Plasma from individual infected mice was pooled at time points 2, 4, 8, and 16 weeks postinfection.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences for the dbpA were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: (B. afzelii A91, XXX; B. garinii 40, YYY; and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA, ZZZ). Published dbpA sequences from B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains BO23 (AF069267), ACA1 (AF069278), PGau (AF069270), U01 (AF069284), Ip90 (AF069258), VSBP (AF069272), PBr (AF069281), JEM4 (AF079362), 297 (U75866), LP4 (AF069271), MC1 (AF079361), HB19 (AF069254), B31 (AF069269), and N40 (AF069252) were obtained from GenBank.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of DbpA of the Finnish borrelial isolates.

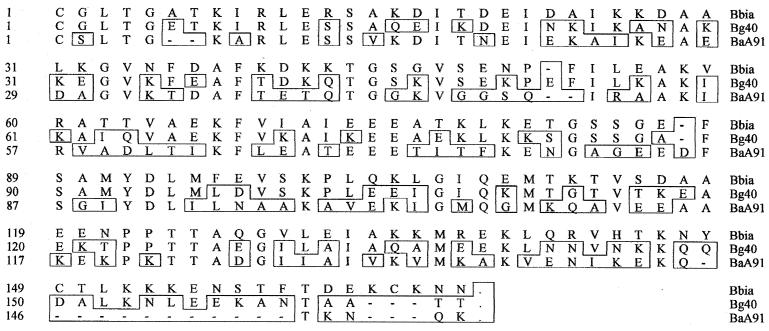

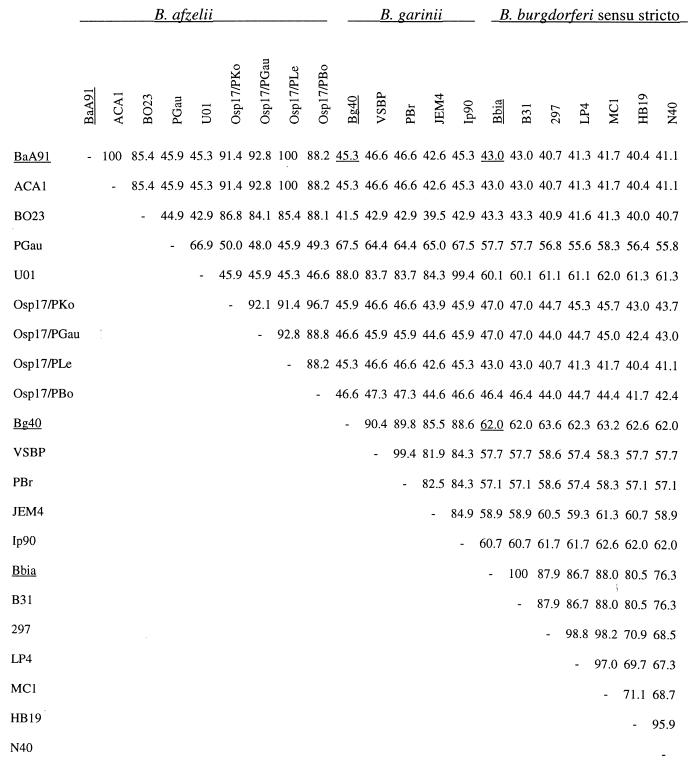

The deduced mature portions of DbpABaA91, DbpABg40, and DbpABbia contained 150, 165, and 167 residues, respectively (Fig. 1). Differences in the amino acid sequences were distributed along the entire sequence, but deletions in DbpABaA91 were near the carboxy terminus. The calculated molecular masses of the predicted mature proteins DbpABaA91, DbpABg40, and DbpABbia (without lipid acylation) were 16.2, 18.0, and 18.5 kDa, respectively. Protein analysis revealed only slight differences in the frequency of charged, polar, and hydrophobic amino acid composition (data not shown), yet the balance between acidic and basic amino acids differed, yielding a calculated pI for DbpABaA91 of 5.69, but pIs of 8.75 and 8.20 for DbpABg40 and DbpABbia, respectively. Comparison of the deduced mature DbpA amino acid sequences of DbpABaA91 and DbpABbia, DbpABaA91 and DbpABg40, and DbpABg40 and DbpABbia showed 43, 45.3, and 62% identity, respectively (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of predicted amino acid sequences of mature DbpA of the Finnish isolates B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA (Bbia), B. garinii 40 (Bg40), and B. afzelii A91 (BaA91). Residues different from those of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA are boxed.

FIG. 2.

Identities of deduced amino acid sequences of DbpA among B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. The percent identities were calculated without the sequence encoding the leader peptide by Multiple sequence alignment, according to the Jotun Hein method, with Lasergene software. Underlined numbers represent identities of DbpA between the Finnish borrelial isolates. BaA91, B. afzelii A91; Bg40,B. garinii 40; Bbia, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA.

B. afzelii sequence analyses.

The amino acid sequence of DbpABaA91 was compared with the published human B. afzelii DbpA sequences from the BO23 (AF069267), ACA1 (AF069278), PGau (AF069270), and U01 (AF069284) strains (Fig. 2). The percentages of deduced mature amino acid sequence identity among them ranged from 45 to 100%. DbpABaA91 protein was identical to that in strain ACA1. The DbpA sequences in strains PGau and U01 showed the highest divergence among the B. afzelii strains: 45.9 and 45.3% identity to DbpABaA91, respectively. The DbpABaA91 sequence was also compared with four published outer surface protein 17 (Osp17) sequences from European B. afzelii strains (22). The identity between DbpABaA91 and the four Osp17 sequences ranged from 88.2 to 100%. The differences in DbpA and Osp17 sequences of B. afzelii strains were evenly spread along the protein.

B. garinii sequence analyses.

The DbpABg40 sequence was compared with published B. garinii DbpA sequences from the Ip90 (AF069258), VSBP (AF069272), PBr (AF069281), and JEM4 (AF079362) strains (Fig. 2). The identity ranged from 85.5 to 90.4%. The differences in the DbpA sequences were located mainly near the carboxy terminus.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto sequence analyses.

The DbpABbia sequence was compared with published DbpA sequences of human B. burgdorferi sensu stricto from the 297 (U75866), LP4 (AF069271), MC1 (AF079361), and HB19 (AF069254) strains and with two sequences from the tick isolates B31 (AF069269) and N40 (AF069252) (Fig. 2). The deduced mature amino acid sequence identity ranged from 76.3 to 100%. The dbpA sequence in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA differs by only one nucleotide (position 100) from the dbpA sequence of strain B31, which does not change the translated amino acid sequence.

Immunoblot reactivity of LB patient samples.

Serum samples from 16 of the 20 LB patients were positive in immunoblots with rDbpABaA91, rDbpABg40, and rDbpABbia as antigens (Table 2). Nine of the 10 patients with NB reacted positively; 4 samples showed immunoreactivity with rDbpABaA91, 5 with rDbpABg40, and 2 with rDbpABbia. Two samples recognized two rDbpAs each—one rDbpABaA91 and rDbpABg40 and the other rDbpABaA91 and rDbpABbia. Seven of the 10 samples from patients with LA were positive; 5 with rDbpABaA91, 3 with rDbpABg40, and 2 with rDbpABbia antigens. One sample showed antibodies against all three rDbpAs, and one had antibodies to rDbpABaA91 and rDbpABg40. Four sera that reacted with two or three rDbpAs showed a strong reaction with one protein, but also some immunoreactivity against the other rDbpAs. All of the control samples were negative against the three rDbpAs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

IgG WB reactivity against recombinant DbpA proteins from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii of LB patients and controls

| Patient/control group | No. of positive WBs/no. of samples

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | rDbpA

|

||||

| B. afzelii A91 | B. garinii 40 | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA | |||

| NBa | 9/10 | 4/10 | 5/10 | 2/10 | |

| LAb | 7/10 | 5/10 | 3/10 | 2/10 | |

| Syphilis | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | |

| Positive for RF | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | |

| IgM positive for EBV | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | |

| Blood donors | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | |

Two samples reacted with two DbpAs.

Two samples reacted with two or three DbpAs.

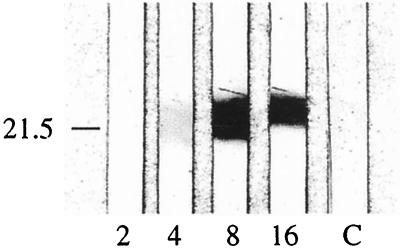

Immunoblot reactivity in mouse samples.

When rDbpABg40 was used as the antigen in the immunoblot assay, weak reactions were observed with the infected mouse plasma 4 weeks postinfection with B. garinii. At 8 and 16 weeks postinfection, the pooled plasma reacted positively with rDbpABg40 (Fig. 3). The infected mouse plasma did not react with rDbpABaA91 or rDbpABbia at any time point (data not shown). Plasma from sham-infected mice was immunoblot negative (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Recombinant DbpA IgG immunoblot with plasma from mice infected with B. garinii. Pooled samples were tested against rDbpABg40 at 2, 4, 8, and 16 weeks postinfection. Control plasma (C) is from sham-infected mice. The value to the left denotes the location of the 21.5-kDa molecular mass standard. The image was produced with an Agfa Arcus II Desktop Scanner and Adobe Photoshop 5.0 and Adobe PageMaker 6.0 software.

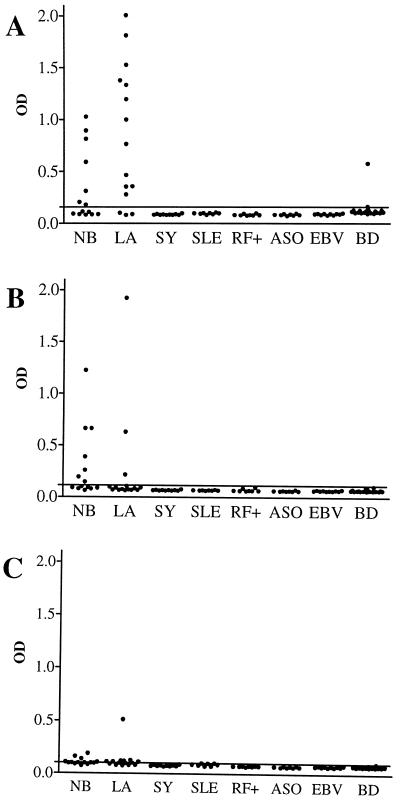

ELISA.

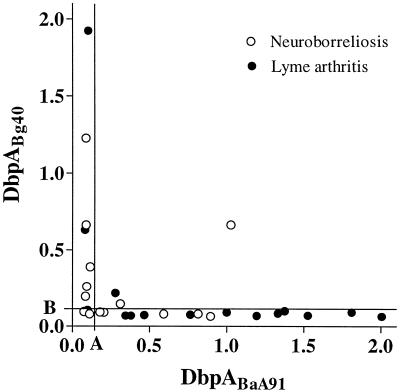

In IgG ELISA, 14 of 14 samples (100%) from patients with NB were positive. Seven of 14 (50%), 7 of 14 (50%), and 6 of 14 (43%) were positive when rDbpABaA91, rDbpABg40, and rDbpABbia, respectively, were used as antigens (Fig. 4). Fourteen of the 15 samples (93%) from patients with LA were positive; 12 of 15 (80%), 3 of 15 (20%), and 9 of 15 (60%) were positive with rDbpABaA91, rDbpABg40, and rDbpABbia, respectively (Fig. 4). The majority of immunoreactivity was against rDbpA from B. afzelii and B. garinii. Of the 26 positive samples with either rDbpABaA91 or rDbpABg40, 23 reacted with one antigen only (Fig. 5). Only three samples “cross-reacted”, and their OD values with the two antigens were equally high. One patient only with LA had a high antibody response against rDbpA from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Fig. 4C). This sample also reacted with the other rDbpAs, but these antibody responses were weak positives. Two samples from patients with NB were positive only for rDbpABbia. The majority of the 15 positive reactions against rDbpABbia were close to the cutoff level (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

IgG ELISA OD values with recombinant DbpA as an antigen from B. afzelii A91 (BaA91 [A]), B. garinii 40 (Bg40 [B]), and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto IA (Bbia [C]) with serum samples from NB and LA patients. Control samples were obtained from patients with syphilis (SY), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), EBV infection, positive for RF (RF+), or positive for antistreptolysin antibody (ASO) and from healthy blood donors (BD). The cutoff level (mean + 3 standard deviations of healthy blood donor samples) is indicated by a line.

FIG. 5.

Correlation between OD values in IgG ELISA with recombinant DbpA from B. afzelii A91 (rDbpABaA91) and B. garinii 40 (rDbpABg40). The cutoff level (mean + 3 standard deviations of healthy blood donor values) for rDbpABaA91 is indicated by line A, and that for rDbpABg40 is indicated by line B. Open circles indicate patients with NB, and solid circles indicate patients with LA.

ELISA of EM patient samples.

We also tested serum samples from culture- or PCR-positive EM patients for anti-DbpA antibodies. In IgM ELISA with rDbpABaA91 or rDbpABg40 as an antigen, 1 or 2 of the 23 samples (4 to 9%) at diagnosis and 1 or 2 (4 to 9%) at the convalescence phase, respectively, were positive (data not shown). In IgG ELISA, 3 or 1 of the 23 samples (13 to 4%) at diagnosis and 4 or 0 (17 to 0%) at the convalescence phase were positive when rDbpABaA91 or rDbpABg40, respectively, was used as an antigen (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We analyzed and compared sequences of DbpA from three European isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii. Compatibly with a previous study (33), we observed high interspecies heterogeneity. Our hypothesis was that the heterogeneity of the amino acid sequences might have major implications for the usefulness of a given antigen in the serodiagnosis of LB. If the antigenic epitopes in the variant proteins were different, the sensitivity of an immunoassay would be low with a single variant antigen only. In the present study, we demonstrate that inclusion of DbpA variants from three pathogenic species of B. burgdorferi as antigens significantly increased the sensitivity of the Western blotting and ELISAs, compared with the use of a single DbpA antigen.

For reliable serodiagnosis of LB, a confirmatory immunoblotting after the ELISA has been advocated. In Europe especially, the use of different species and strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato as sources of antigens leads to inconsistent results because of variations in the expression of the immunogenic proteins (18, 34). Furthermore, immunoblotting not only is a tedious procedure in the laboratory routine, but also is prone to subjective interpretations of band intensities. A recent European multicenter study formulated a panel of seven immunoblotting rules to be adopted in relation to the characteristics of LB in local areas (34). In another European study, exclusion of EBV and cytomegalovirus infections by appropriate serology gave better predictive power than confirmation with immunoblotting after the ELISA (11). Beyond any doubt, this emphasizes the need for novel methods that would be standardized at least with regard to performance, relevance, techniques, and antigen preparation. Use of recombinant antigens is an option. In the present study, rDbpAs from B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates seemed to be sensitive and specific antigens in the WB and ELISAs for disseminated LB. Among well-defined patients with LA or NB, up to 93 to 100% of samples reacted positively with rDbpAs. WB results and quantification of immunoreactivities by ELISA provided evidence for the species specificity of serological responses. In the majority of cases with positive reactions against more than one DbpA variant proteins, the immunoreactivity was superior against one DbpA antigen. Moreover, the absence of immunoreactivity in non-Lyme sera indicates specificity of DbpA antigens.

Unfortunately, the low sensitivity of IgM and IgG serology for EM limits the utility of rDbpA as a diagnostic antigen in early stages of LB. This has been the experience with several other recombinant borrelial antigens (27, 28). Obviously, the immunological properties and/or differences in expression of the DbpA molecule account for the delayed antibody response during the course of Lyme disease. Also, it is unclear at the moment whether early antibiotic treatment of EM patients would have contributed to our inability to detect anti-DbpA antibodies when using convalescent-phase sera.

To our knowledge, only one study has evaluated immune responses to rDbpA in the serodiagnosis of human LB (7). In Italian patients, immune responses to rDbpA from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto 297 were detected in 13% of patients with EM and 35% of those with disseminated LB (NB and LA). In children with suspected LB, by using rDbpA originating from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto N40, we observed the immunoreactivity to be at approximately the same level (unpublished observations). The proportion of samples reacting with rDbpA from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the present study is in accord with the previous results. These findings are probably due to heterogeneity of the proteins resulting in differences in the epitope specificity of the antibodies. In the present study, the predominance of immunoreactivity to rDbpA from B. afzelii and B. garinii is compatible with the greater prevalence of these two genospecies compared to that of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in Europe (24, 41).

The immunoreactivity to DbpA in experimental murine borreliosis in this study supports the species specificity of LB serology. The antibody response in infected mice corresponds to that in earlier studies, in which detectable antibody levels were seen at 2 to 4 weeks postinfection (9, 14, 15). Feng et al. (9) observed some cross-reactivity of antibodies against heterologous DbpA. They reported that plasma from mice infected with the B. afzelii PKo strain or B. garinii PBi strain reacted against rDbpA from genetically distant B. burgdorferi sensu stricto N40, yet at significantly lower levels than those against plasma from mice infected with homologous B. burgdorferi sensu stricto N40. These data suggest some degree of cross-reactivity among isolates of antigenically divergent B. burgdorferi sensu lato. In fact, this is in line with the observed differences in the immune responses to the DbpA variants in the present study.

A recent study described a novel immunodominant outer surface protein of B. afzelii, Osp17 (22); sequence similarities with DbpA suggested a relationship between this protein and DbpA. In that study, osp17 genes could not be amplified from B. garinii or B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains, indicating heterogeneity between the sequences. Interestingly, on comparison of the four published Osp17 sequences with the DbpA sequence from the B. afzelii strain in the present study (DbpABaA91), the identity of the sequences was 88 to 100%. In contrast, the homology of the Osp17 sequences and DbpA sequences from B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was approximately 45%, corresponding to that of DbpABaA91 and DbpA from B. garinii and B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. Taken together, the close homology between DbpA and Osp17 from the B. afzelii strains suggests that these proteins represent species-specific variants of the same (ancestral) protein. Even more definitely, on the basis of genetic and biochemical evidence, Ulbrandt et al. (40) very recently concluded that Osp17 and DbpA from B. afzelii strain Pko are the same protein. The Osp17 antigen from this particular borrelial strain has been proposed as a component in a new recombinant serodiagnostic immunoblot (42), with seropositivity of 24 to 36% in patients with early disseminated borreliosis and up to 85% in patients with late disease (30, 42). It is obvious that inclusion of rDbpAs (Osp17) derived from different strains would increase the sensitivity of the recombinant blot.

The high sequence heterogeneity of DbpA among the three borrelial subspecies raises interesting considerations regarding the potential differences in the interaction between this protein and the host immune system. The DbpA of B. burgdorferi has been suggested to have a biological function (i.e., decorin binding activity) (12, 13), during the mammalian phase of LB. This ability is believed to be important for promoting colonization by the spirochetes when they penetrate into the skin via a tick bite and adhere to the collagen-associated proteoglycan decorin (15). Evaluation of the decorin binding activity of our DbpA constructs was beyond the scope of this study. However, the critical lysine residues responsible for this activity (4) were present in all three Finnish human isolates of B. burgdorferi sensu lato examined (data not shown). The heterogeneity of DbpA proteins may also have implications for the vaccine development of this antigen (6, 15, 16). Although a recent study suggests that conformational epitopes are needed to elicit protective antibodies against homologous and heterologous strains (40), the present findings on the species specificity of serologic responses to DbpA imply that development of a wide-spectrum vaccine may be more complicated than anticipated.

In conclusion, DbpA seems to be a sensitive and specific antigen for the serodiagnosis of LA or NB, provided that variants from all pathogenic borrelial species are included in the antigen set. This approach may reduce the number of false-negative results. The present findings also imply that DbpA antigens might be used for the species-specific serodiagnosis of LA and NB. These characteristics could be useful at least for epidemiologic purposes, as well as, possibly, prognostic or therapeutic purposes. It has been shown that the three pathogenic borrelial subspecies are preferentially associated with distinct clinical pictures (41). Moreover, a recent study suggested that even at the subspecies level, certain strains, on the basis of genetic diversity of ospC genes, might cause more invasive or severe disease than other strains (2). Given the well-known difficulties in detecting borreliae from clinical samples, either by culture or PCR, it can be speculated that knowledge of the causative borrelial subspecies might be beneficial when evaluating the course of the disease and intensity of the antibiotic therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Foundation for Pediatric Research, Finland; the National Technology Agency (TEKES), Finland; and the Helsinki Central Hospital Research Funds, Finland.

We thank Matti Viljanen for donating the B. burgdorferi strains used in this study. The support and collaboration of Michael Norgard and Kayla Hagman are gratefully acknowledged. English usage was checked by Jean Margaret Perttunen.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baranton, G., D. Postic, I. Saint Girons, P. Boerlin, J.-C. Piffaretti, M. Assous, and P. A. D. Grimont. 1992. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:378-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranton, G., G. Seinost, G. Theodore, D. Postic, and D. Dykhuizen. 2001. Distinct levels of genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with different aspects of pathogenicity. Res. Microbiol. 152:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaauw, A. A. M., A. M. van Loom, J. F. P. Schellecens, and J. W. J. Bijlsma. 1999. Clinical evaluation of guidelines and two-test approach for Lyme disease. Rheumatology 38:1121-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, E. L., B. P. Guo, P. O'Neal, and M. Höök. 1999. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi. Identification of critical lysine residues in DbpA required for decorin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26272-26278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, S. L., S. L. Hansen, and J. J. Langone. 1999. Role of serology in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. JAMA 282:62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassatt, D. R., N. K. Patel, N. D. Ulbrandt, and M. S. Hanson. 1998. DbpA, but not OspA, is expressed by Borrelia burgdorferi during spirochetemia and is a target for protective antibodies. Infect. Immun. 66:5379-5387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cinco, M., M. Ruscio, and F. Rapagna. 2000. Evidence of Dbps (decorin binding proteins) among European strains of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and in the immune response of LB patient sera. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellinger, W., A. Farencena, B. Redl, V. Sambri, R. Cevenini, and G. Stoffler. 1995. Amino acid sequence heterogeneity of chromosomal encoded Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato major antigen P100. New Microbiol. 18:163-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng, S., E. Hodzic, B. Stevenson, and S. W. Barthold. 1998. Humoral immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi N40 decorin binding proteins during infection of laboratory mice. Infect. Immun. 66:2827-2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber, M. A., E. D. Shapiro, G. L. Bell, A. Sampieri, and S. J. Padula. 1995. Recombinant outer surface protein C ELISA for the diagnosis of early Lyme disease. J. Infect. Dis. 171:724-727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goossens, H. A. T., A. E. van den Bogaard, and M. K. E. Nohlmans. 1999. Evaluation of fifteen commercially available serological tests for diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 18:551-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo, B. P., S. J. Norris, L. C. Rosenberg, and M. Höök. 1995. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect. Immun. 63:3467-3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, B. P., E. L. Brown, D. W. Dorward, L. C. Rosenberg, and M. Höök. 1998. Decorin-binding adhesins from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 30:711-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagman, K. E., P. Lahdenne, G. Popova, S. F. Porcella, D. R. Akins, J. D. Radolf, and M. V. Norgard. 1998. Decorin-binding protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is encoded within a two-gene operon and is protective in the murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 66:2674-2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanson, M. S., D. R. Cassat, B. P. Guo, N. K. Patel, M. P. McCarthy, D. W. Dorward, and M. Höök. 1998. Active and passive immunity against Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A (DbpA) protects against infection. Infect. Immun. 66:2143-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson, M. S., N. K. Patel, D. R. Cassat, and N. D. Ulbrandt. 2000. Evidence for vaccine synergy between Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A and outer surface protein A in the mouse model of Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 68:6457-6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauser, U., and B. Wilske. 1997. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with recombinant internal flagellin fragments derived from different species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato for the serodiagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 186:145-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauser, U., H. Krahl, H. Peters, V. Fingerle, and B. Wilske. 1998. Impact of strain heterogeneity on Lyme disease serology in Europe: comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using different species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:427-436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hauser, U., G. Lehnert, and B. Wilske. 1998. Diagnostic value of proteins of three Borrelia species (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato) and implications for development and use of recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:456-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauser, U., G. Lehnert, and B. Wilske. 1999. Validity of interpretation criteria for standardized Western blots (immunoblots) for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis based on sera collected throughout Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2241-2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauris-Heipke, S., R. Fuchs, M. Motz, V. Preac-Mursic, E. Schwab, E. Soutschek, G. Will, and B. Wilske. 1993. Genetic heterogeneity of the genes coding for the outer surface protein C (OspC) and the flagellin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 182:37-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jauris-Heipke, S., B. Roessler, G. Wanner, C. Habermann, D. Rössler, V. Fingerle, G. Lehnert, R. Lobentanzer, I. Pradel, B. Hillenbrand, U. Schulte-Spechtel, and B. Wilske. 1999. Osp17, a novel immunodominant outer surface protein of Borrelia afzelii: recombinant expression in Escherichia coli and its use as a diagnostic antigen for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Junttila, J., R. Tanskanen, and J. Tuomi. 1994. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in selected tick populations in Finland. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 26:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila, J., M. Peltomaa, H. Soini, M. Marjamäki, and M. K. Viljanen. 1999. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus ticks in urban recreational areas of Helsinki. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1361-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrenz, M. B., J. M. Hardman, R. T. Owens, J. Nowakowski, A. C. Steere, G. P. Wormser, and S. J. Norris. 1999. Human antibody responses to VlsE antigenic variation protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3997-4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang, F. T., A. C. Steere, A. R. Marques, B. J. B. Johnson, J. N. Miller, and M. T. Philipp. 1999. Sensitive and specific serodiagnosis of Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a peptide based on an immunodominant conserved region of Borrelia burgdorferi VlsE. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3990-3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnarelli, L. A., E. Fikrig, S. J. Padula, J. F. Anderson, and R. A. Flavell. 1996. Use of recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi in serologic tests for diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:237-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnarelli, L. A., J. W. Ijdo, S. J. Padula, R. A. Flavell, and E. Fikrig. 2000. Serologic diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with recombinant antigens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1735-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadelman, R. B., and G. P. Wormser. 1998. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 352:557-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pohl-Koppe, A., A. Kaunicnik, and B. Wilske. 2001. Characterization of the cellular and humoral immune response to outer surface protein C and outer surface protein 17 in children with early disseminated Lyme borreliosis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 189. [Online.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Rauer, S., M. Kayser, U. Neubert, C. Rasiah, and A. Vogt. 1995. Establishment of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using purified recombinant 83-kilodalton antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2596-2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rauer, S., N. Spohn, C. Rasiah, U. Neubert, and A. Vogt. 1998. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant OspC and the internal 14-kDa flagellin fragment for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:857-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts, W. C., B. A. Mullikin, R. Lathigra, and M. S. Hanson. 1998. Molecular analysis of sequence heterogeneity among genes encoding decorin binding proteins A and B of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Infect. Immun. 66:5275-5285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson, J., E. Guy, N. Andrews, B. Wilske, P. Anda, M. Granström, U. Hauser, Y. Moosmann, V. Sambri, J. Schellekens, G. Stanek, and J. Gray. 2000. A European multicenter study of immunoblotting in serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2097-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roessler, D., U. Hauser, and B. Wilske. 1997. Heterogeneity of BmpA (P39) among European isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and influence of interspecies variability on serodiagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2752-2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seppälä, I. J. T., R. Kroneld, K. Schauman, K. O. Forsen, and R. Lassenius. 1994. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: non-specific serological reactions with Borrelia burgdorferi sonicate antigen caused by IgG2 antibodies. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:293-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigal, L. H. 1998. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheum. 41:195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steere, A. C. 1995. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease, Lyme borreliosis), p. 2143-2155. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Churchill Livingstone, New York, N.Y.

- 39.Straubinger, R. K. 2000. PCR-based quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi organisms in canine tissues over a 500-day postinfection period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2191-2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulbrandt, N. D., D. R. Cassatt, N. K. Patel, W. C. Roberts, C. M. Bachy, C. A. Fazenbaker, and M. S. Hanson. 2001. Conformational nature of the Borrelia burgdorferi decorin binding protein A epitopes that elicit protective antibodies. Infect. Immun. 69:4799-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, G., A. P. van Dam, I. Schwartz, and J. Dankert. 1999. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: taxonomic, epidemiologic, and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:633-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilske, B., C. Habermann, V. Fingerle, B. Hillenbrand, S. Jauris-Heipke, G. Lehnert, I. Pradel, D. Roessler, and U. Schulte-Spechtel. 1999. An improved recombinant IgG immunoblot for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 188:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wormser, G. P., J. Nowakowski, R. B. Nadelman, S. Bittker, D. Cooper, and C. Pavia. 1998. Improving the yield of blood cultures for patients with early Lyme disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:296-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]