Abstract

Seven isoniazid-resistant isolates with mutations in the NADH dehydrogenase (ndh) gene were molecularly typed by IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. All seven isolates with the R268H mutation had identical 1.4-kb IS6110 fingerprints. High-resolution minisatellite-based typing discriminated five of these isolates; two isolates were identical.

DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is useful for the molecular epidemiological analysis of transmission of infection. The most commonly used method is IS6110 fingerprinting (18), which has been used to trace outbreaks in hospitals (6, 8, 15), prisons (8), and communities (2, 4, 7, 20) and for epidemiological studies within countries (14, 16, 19). However, comparison of data obtained by this technique from different laboratories is difficult due to the lack of reproducibility (9) and portability. Another limitation of this technique is that isolates with small numbers of IS6110 copies are not easily analyzed.

Recently, a high-resolution minisatellite typing method based on variable-number tandem repeats (VNTRs) of genetic elements called mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs) was described (12, 17). This PCR-based typing method used 12 MIRU-VNTR loci and was found to provide a level of resolution comparable to that obtained by typing with IS6110. Furthermore, epidemiologically related isolates were found to cluster together, and genetic relationships inferred from MIRU-VNTR typing and typing by IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis correlated significantly.

In the present study, seven isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates, all with the R268H mutation in the NADH dehydrogenase (ndh) gene and with identical single-band IS6110 fingerprints (11), were retyped by the MIRU-VNTR minisatellite typing method in order to determine if the latter method could discriminate the isolates.

Isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates were collected from the Central Tuberculosis Laboratory in Singapore as part of a study of isoniazid and rifampin resistance (3, 10). Drug susceptibility testing was done by the BACTEC 460 (Becton Dickinson, Towson, Md.) radiometric method, and the isoniazid concentration was 0.1 μg/ml.

DNA fingerprinting of M. tuberculosis isolates was done by the standard IS6110-based RFLP analysis method (18). Each of these clinical isolates was obtained from a different individual. Seven isoniazid-resistant isolates with identical single-copy IS6110 fingerprints were also analyzed by the recently described high-resolution minisatellite-based typing method (12, 17), except that the annealing temperature for the MIRU 24 locus was increased to 55°C. The MIRU 4 reverse primer was changed to 5"GCG CAG CAG AAA CGC CAG C (the change is indicated in boldface), as this resulted in more specific bands. PCR products were run as described previously (17) by using a 100-bp ladder (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.).

The M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome, downloaded from Gen-Bank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PMGifs/Genomes/micr.html), was examined to determine the expected sizes of the PCR products. This information, together with information regarding the numbers of repeats and the sizes of the MIRUs (17), is tabulated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

MIRU locus information for M. tuberculosis H37Rv

| MIRU locus | No. of repeats | Size of repeat (bp) | Size of PCR product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 53 | 508 |

| 4 | 3 | 77 | 353 |

| 10 | 3 | 53 | 643 |

| 16 | 2 | 53 | 671 |

| 20 | 2 | 77 | 591 |

| 23 | 6 | 53 | 873 |

| 24 | 1 | 52 | 447 |

| 26 | 3 | 51 | 614 |

| 27 | 3 | 53 | 657 |

| 31 | 3 | 53 | 651 |

| 39 | 2 | 53 | 646 |

| 40 | 1 | 54 | 408 |

IS6110 fingerprinting of seven M. tuberculosis clinical isolates with mutations in the ndh gene showed that all seven isolates with the R268H alteration had identical 1.4-kb IS6110 fingerprints.

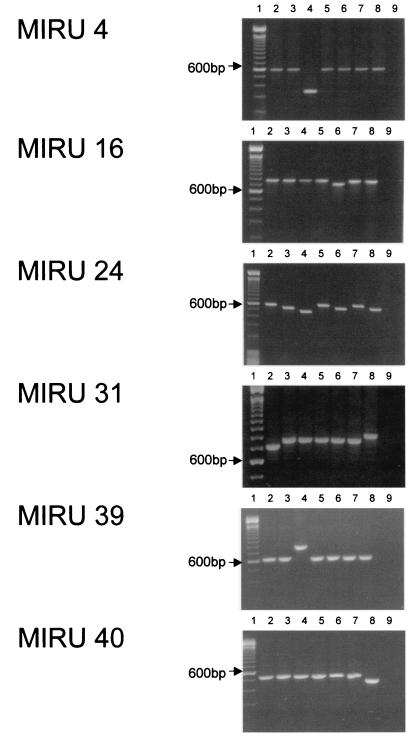

The seven isolates were typed by minisatellite-based typing with the 12 MIRU loci and various numbers of copies of the 51- to 77-bp MIRUs. The MIRU copy numbers in the 12 MIRU-VNTR loci are shown in Table 2. These copy numbers were determined on the basis of the information provided in Table 1. Representative examples of the results of PCR analysis are shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

MIRU copy numbers for seven isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates

| MIRU locus | No. of copies for isolate:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I19 | I54 | I72 | I85 | I87 | I89 | I90 | |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| 10 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 23 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 24 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 26 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 27 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 31 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| 39 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 40 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

FIG. 1.

PCR analysis of representative MIRU loci. Lanes 1, 100-bp ladder (with the stronger 600-bp band indicated); lanes 2 to 8, PCR products from M. tuberculosis isolates I19, I54, I72, I85, I87, I89, and I90, respectively; lanes 9, negative control.

As shown in Table 2, isolates I85 and I89 have identical MIRU types. Pairwise comparisons of the isolates have been done, and the number of differences in the loci between the isolates are shown in Table 3. For example, there is one MIRU repeat difference (MIRU locus 31) between I19 and I85, but all the other loci are identical. Hence, isolates with larger numbers of differences are genetically distant. Isolate I72 is genetically distant from all the other isolates, having six or seven MIRU repeat differences compared with the numbers of MIRUs in the other isolates.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise comparisons between strains showing the number of differences at MIRU loci

| Isolate | No. of differences

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I54 | I72 | I85 and I89a | I87 | I90 | |

| I19 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| I54 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| I72 | 6 | 7 | 7 | ||

| I85 and I89a | 2 | 4 | |||

| I87 | 4 | ||||

Isolates I85 and I89 have identical MIRU types.

MIRU-VNTR analysis was able to discriminate the isolates in the samples (Table 2; Fig. 1). Of the seven isolates with identical IS6110 fingerprints, only two isolates, I85 and I89, were identical. For epidemiological investigations, IS6110 fingerprinting is the most widely used technique. In order to discriminate strains with few copies of IS6110, assays such as spoligotyping (1, 9), which is a PCR-based assay, and polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence (PGRS) fingerprinting with recombinant plasmid pTBN12 (21) have been used. Spoligotyping detects 43 known spacer sequences which are interspersed among the direct repeats (DRs) in the DR region of M. tuberculosis complex strains (9). The discriminatory power of spoligotyping has been found to be poorer than that of typing by IS6110 fingerprinting (9) and PGRS fingerprinting (21). A comparison of spoligotyping and PGRS fingerprinting showed that the latter method had a greater power to discriminate among isolates with small numbers of copies of IS6110 (21). Further work is required to compare the discriminatory power of the PGRS fingerprinting method with the MIRU-VNTR method used in the present study.

When the seven isolates with the R268H alteration and single-copy IS6110 fingerprints are excluded, single-copy IS6110 fingerprints were present in only 12 of 215 (5.6%) drug-resistant clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis from Singaporean patients (unpublished data). This suggests that the seven isolates with the R268H mutation have a single common ancestor, since the probability that six subsequent strains will have the single-copy IS6110 fingerprint is only (0.056)6, or 3 × 10−8.

Furthermore, MIRU-VNTR profiles have been estimated to be stable for at least 18 months (12), while IS6110-based RFLP patterns have been observed to have a high degree of stability. Niemann et al. (13) estimated a rate of sequence change of ∼1.9% per possible transmission. After several passages through human hosts, recombination has produced variations in the MIRU-VNTR profiles in the isolates used in the present study. Thus, these strains may have evolved from one original strain with the R268H mutation and the 1.4-kb single-copy IS6110 fingerprint.

The present study has also shown that a comparison of the sizes of the PCR products is adequate for discrimination of the isolates (Fig. 1). Determination of the number of repeats requires knowledge of the size of the repeat for each of the MIRUs as well as the size of the PCR product (Table 1). As the sizes of the MIRU repeats range from 51 to 77 bp, isolates with different number of repeats are easily discriminated by PCR analysis. However, for comparisons between laboratories, a record of the number of repeats for each MIRU locus would allow the portability of results.

The advantages of the use of the MIRU-VNTR method over the use of the IS6110 fingerprinting method are that it is easy to set up; it yields results within a day, as it is PCR based; it is relatively inexpensive; and it is easily adaptable to a standard molecular biology laboratory even in less developed countries. Most importantly, the MIRU-VNTR method is able to discriminate isolates with small numbers of copies of IS6110, which account for >40% of isolates from India (5) and from Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam (14).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Central Tuberculosis Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, for providing isolates. We are grateful to the Clinical Research Unit, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, for administrative support and the staff of the Clinical Immunology Laboratory, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, for use of equipment.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Medical Research Council of Singapore (grant NMRC/329/1999).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer, J., A. B. Andersen, K. Kremer, and H. Miorner. 1999. Usefulness of spoligotyping to discriminate IS6110 low-copy-number Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains cultured in Denmark. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2602-2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bifani, P. J., B. Mathema, Z. Liu, S. L. Moghazeh, B. Shopsin, B. Tempalski, J. Driscol, R. Frothingham, J. M. Musser, P. Alcabes, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Identification of a W variant outbreak of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via population-based molecular epidemiology. JAMA 282:2321-2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudville, I. C., S. Y. Wong, and I. Snodgrass. 1997. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore 26:549-556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, W. Z., J. Koehler, H. El-Hajj, P. C. Hopewell, A. L. Reingold, C. B. Agasino, M. D. Cave, S. Rane, Z. Yang, C. M. Crane, and P. M. Small. 1998. Dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis across the San Francisco Bay area. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1104-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das, S., C. N. Paramasivan, D. B. Lowrie, R. Prabhakar, and P. R. Narayanan. 1995. IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Madras, south India. Tuber. Lung Dis. 76:550-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frieden, T. R., L. F. Sherman, K. L. Maw, P. I. Fujiwara, J. T. Crawford, B. Nivin, V. Sharp, D. Hewlett, Jr., K. Brudney, D. Alland, and B. N. Kreisworth. 1996. A multi-institutional outbreak of highly drug-resistant tuberculosis: epidemiology and clinical outcomes. JAMA 276:1229-1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey-Faussett, P., P. Sonnenberg, S. C. Shearer, M. C. Bruce, C. Mee, L. Morris, and J. Murray. 2000. Tuberculosis control and molecular epidemiology in a South African gold-mining community. Lancet 356:1066-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutierrez, M. C., V. Vincent, D. Aubert, J. Bizet, O. Gaillot, L. Lebrun, C. Le Pendeven, M. P. Le Pennec, D. Mathieu, C. Offredo, B. Pangon, and C. Pierre-Audigier. 1998. Molecular fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and risk factors for tuberculosis transmission in Paris, France, and surrounding area. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:486-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kremer, K., D. van Soolingen, R. Frothingham, W. H. Haas, P. W. Hermans, C. Martin, P. Palittapongarnpim, B. B. Plikaytis, L. W. Riley, M. A. Yakrus, J. M. Musser, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2607-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, A. S. G., I. H. K. Lim, L. L. H. Tang, A. Telenti, and S. Y. Wong. 1999. Contribution of kasA analysis to detection of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Singapore. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2087-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, A. S. G., A. S. M. Teo, S. Y. Wong. 2001. Novel mutations in the ndh gene in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2157-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazars, E., S. Lesjean, A.-L. Banuls, M. Gilbert, V. Vincent, B. Gicquel, M. Tibayrenc, C. Locht, and P. Supply. 2001. High-resolution minisatellite-based typing as a portable approach to global analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis molecular epidemiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:1901-1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niemann, S., S. Rusch-Gerdes, E. Richter, H. Thielen, H. Heykes-Uden, and R. Diel. 2000. Stability of IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains in actual chains of transmission. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2563-2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park, Y. K., G. H. Bai, and S. J. Kim. 2000. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from countries in the western Pacific region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:191-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterling, T. R., D. S. Pope, W. R. Bishai, S. Harrington, R. R. Gershon, and R. E. Chaisson. 2000. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from a cadaver to an embalmer. N. Engl. J. Med. 342:246-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suffys, P. N., M. E. Ivens de Araujo, M. L. Rossetti, A. Zahab, E. W. Barroso, A. M. Barreto, E. Campos, D. van Soolingen, K. Kremer, H. Heersma, and W. M. Degrave. 2000. Usefulness of IS6110-restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of Brazilian strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and comparison with an international fingerprint database. Res. Microbiol. 151:343-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Supply, P., E. Mazars, S. Lesjean, V. Vincent, B. Gicquel, and C. Locht. 2000. Variable human minisatellite-like regions in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Mol. Microbiol. 36:762-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Embden, J. D., M. D. Cave, J. T. Crawford, J. W. Dale, K. D. Eisenach, B. Gicquel, P. Hermans, C. Martin, R. McAdam, T. M. Shinnick, and P. M. Small. 1993. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:406-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Soolingen, D., M. W. Borgdorff, P. E. de Haas, M. M. Sebek, J. Veen, M. Dessens, K. Kremer, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in The Netherlands: a nationwide study from 1993 through 1997. J. Infect. Dis. 180:726-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaganehdoost, A., E. A. Graviss, M. W. Ross, G. J. Adams, S. Ramaswamy, A. Wanger, R. Frothingham, H. Soini, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Complex transmission dynamics of clonally related virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with barhopping by predominantly human immunodeficiency virus-positive gay men. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1245-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, Z. H., K. Ijaz, J. H. Bates, K. D. Eisenach, and M. D. Cave. 2000. Spoligotyping and polymorphic GC-rich repetitive sequence fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains having few copies of IS6110. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3572-3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]