Abstract

Flagellate green algae have developed a visual system, the eyespot apparatus, which allows the cell to phototax. To further understand the molecular organization of the eyespot apparatus and the phototactic movement that is controlled by light and the circadian clock, a detailed understanding of all components of the eyespot apparatus is needed. We developed a procedure to purify the eyespot apparatus from the green model alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Its proteomic analysis resulted in the identification of 202 different proteins with at least two different peptides (984 in total). These data provide new insights into structural components of the eyespot apparatus, photoreceptors, retina(l)-related proteins, members of putative signaling pathways for phototaxis and chemotaxis, and metabolic pathways within an algal visual system. In addition, we have performed a functional analysis of one of the identified putative components of the phototactic signaling pathway, casein kinase 1 (CK1). CK1 is also present in the flagella and thus is a promising candidate for controlling behavioral responses to light. We demonstrate that silencing CK1 by RNA interference reduces its level in both flagella and eyespot. In addition, we show that silencing of CK1 results in severe disturbances in hatching, flagellum formation, and circadian control of phototaxis.

INTRODUCTION

Flagellate green algae can perceive light information via a primitive visual system, the eyespot apparatus. Light causes two major types of behavioral responses in these algae. One is phototaxis, the directed swimming toward or away from the light source. The other, photoshock, is observed when the cells experience a large and sudden change in light intensity. In most green algae, the photoshock response is accompanied by a transient stop in movement, followed by a short period of backward swimming, after which normal forward swimming in a random direction is resumed. So far, only a few molecular signaling components of these two behavioral responses to light are known. Both involve transmembrane Ca2+ fluxes, which finally lead to temporary changes in flagellar beating. In addition, excitation of rhodopsins located in the eyespot apparatus initiates a cascade of rapid electrical responses finally leading to changes in flagellar beating and peculiar photoresponses (reviewed in Nultsch, 1975; Witman, 1993; Kreimer, 2001; Sineshchekov and Govorunova, 2001; Kateriya et al., 2004).

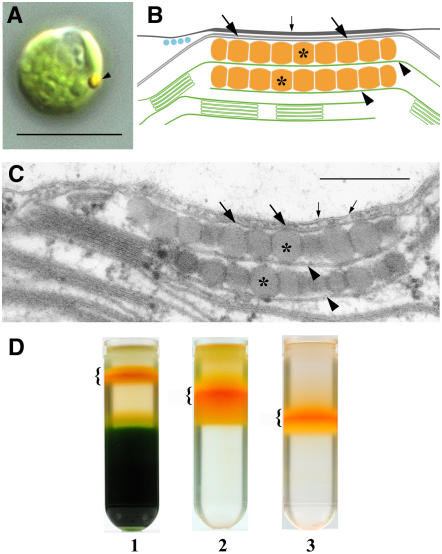

In the light microscope, the eyespot is seen peripherally near the cell's equator as a conspicuous, singular orange-red spot (Figure 1A). The ultrastructure of the functional eyespot apparatus is complex and involves local specializations of membranes from different compartments (reviewed in Melkonian and Robenek, 1984; Kreimer, 2001). In the green model alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the eyespot apparatus is usually composed of two highly ordered layers of carotenoid-rich lipid globules inside the chloroplast (Figures 1B and 1C). The globules exhibit a remarkably constant diameter of 80 to 130 nm and are subtended by a thylakoid membrane. Additionally, the outermost globule layer is attached to specialized areas of the two chloroplast envelope membranes and the adjacent plasma membrane (Figures 1B and 1C). The plasma membrane and the outer chloroplast envelope membrane above the eyespot globules are extremely rich in intramembrane particles resembling most likely membrane proteins (Melkonian and Robenek, 1984).

Figure 1.

Eyespot Location, Structure, and Isolation of a Fraction Enriched in Eyespot Apparatuses by Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation.

(A) Differential interference contrast image of a living cell. The arrow indicates the position of the carotenoid-rich eyespot apparatus. Bar = 10 μm.

(B) Schematic drawing of the eyespot apparatus of C. reinhardtii illustrating the different components of this complex light sensor. Asterisks indicate the carotenoid-rich eyespot globule layers inside the chloroplast, which are associated with thylakoids (arrowheads). The outermost layer is associated with the chloroplast envelope (large arrows). The plasma membrane (small arrow) is closely attached to the chloroplast envelope in the region overlying the eyespot globule layers. In addition, the plasma membrane and the outer chloroplast envelope are enriched in intramembrane particles in this area.

(C) Transmission electron micrograph of the eyespot apparatus of C. reinhardtii. Labeling was done according to (B). Bar = 300 nm.

(D) Distribution of the fraction enriched in eyespot apparatuses (brackets) after flotation on discontinuous sucrose gradients. 1, separation of the cell homogenate; 2, separation of the fraction after the first purification step; 3, separation of the fraction after the second purification step.

The photoreceptors identified so far are generally believed to be located in this plasma membrane patch. Phototaxis requires the cell to determine the direction of incident light. C. reinhardtii most likely accomplishes this by monitoring the modulation of the light intensity reaching its photoreceptors as the cell rolls around its longitudinal cell axis during helical forward swimming. The eyespot globule layers are important for modulation of the light intensity. They confer increased directionality and contrast to the photoreceptors by a dual action. First, they shield them from light passing through the cell body. Second, they reflect light falling directly on the eyespot that is not absorbed by the photoreceptors back onto the overlying plasma membrane. Thus, reflection amplifies the light signal at the photoreceptor location and thereby increases their excitation probability (Foster and Smyth, 1980; Kreimer and Melkonian, 1990; Kreimer et al., 1992; Witman, 1993). Both absorption and reflection increase the front-to-back contrast at the location of the photoreceptors up to eightfold (Harz et al., 1992). In addition, the optical properties of the eyespot apparatus and thereby the generated signal are influenced by the swimming direction relative to the light source (Hegemann and Harz, 1998). Briefly, the signal received by the eyespot apparatus is low and nearly constant when the swimming direction of the cells is well aligned with the light direction but changes when swimming direction deviates from light direction. This periodic signal is then processed in an as yet unknown way and finally initiates corrective flagellar responses to realign the swimming path. Thus, the whole complex (i.e., the specialized membranes and the eyespot globules forming the functional eyespot apparatus) is important for optimal performance of this primitive visual system. This has been demonstrated by analysis of mutants defective in the formation of the eyespot globule layers (Morel-Laurens and Feinleib, 1983; Kreimer et al., 1992). Due to the elaborate structures of algal eyespot apparatuses and the known presence of rhodopsins in some lineages, algae are thought to play an important role in the evolution of photoreception and eyes (Gehring, 2004). Therefore, the structural components forming this early visual system and the signaling cascade from the photoreceptor(s) to tactic movements are not only of great interest to plant biologists but also for developmental and other biologists. This is highlighted by the fact that one of the rhodopsin-like photoreceptors of C. reinhardtii can light-stimulate neurons and trigger behavioral responses in Caenorhabditis elegans (Boyden et al., 2005; Nagel et al., 2003, 2005).

In C. reinhardtii, several mutations affecting eyespot assembly and positioning are known (Hartshorne, 1953; Morel-Laurens and Feinleib, 1983; Pazour et al., 1995; Lamb et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2001; Roberts et al., 2001). Five loci solely involved in formation and/or correct positioning of the eyespot apparatus have been identified so far. The mutant approach has recently led to identification of two genes (min1 and eye2) that are involved in eyespot assembly (Roberts et al., 2001; Dieckmann, 2003). In min1 mutant strains, only miniature eyespots are formed, whereas mutations in eye2 induce loss of a visible eyespot. However, individual eyespot globules are still detectable by electron microscopy in the mutant eye2 (Lamb et al., 1999). Thus, general formation of the globules is probably not affected. The eye2 gene product belongs to the thioredoxin superfamily and exhibits no overall homology to any protein in the databases. EYE2 might act as a specific chaperone in eyespot assembly. The min1 gene also encodes a protein with little homology to known proteins (Dieckmann, 2003). In addition to these proteins important for eyespot development and size control, only four proteins related to function of the eyespot apparatus have been identified so far at the molecular level. These are the two unique seven-transmembrane domain photoreceptors COP3 and COP4, which both act as directly light-gated ion channels (Nagel et al., 2002, 2003; Sineshchekov et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2003; Govorunova et al., 2004). It should be noted that the same proteins have been named differently by independent research groups (see Table 1 for the different nomenclature). COP3 and COP4 can initiate extremely fast depolarizations. Consequently, a truncated COP4, which is permeable to monovalent and divalent cations (Nagel et al., 2003), has recently been expressed in mammalian neurons and used for their light stimulation (Boyden et al., 2005) as already indicated above. In addition, two splicing variants of the abundant retinal binding protein COP (COP1 and COP2) were identified (Deininger et al., 1995; Fuhrmann et al., 2003). Although original experiments suggested these proteins as photoreceptors (Deininger et al., 1995), their silencing showed that they are not acting as photoreceptors in phototaxis and photoshock (Fuhrmann et al., 2001). Based on conserved domain structures, further putative retinal binding proteins encoded in the genome of C. reinhardtii have recently been postulated to be also involved in phototaxis (Kateriya et al., 2004), but in these cases a functional proof is still missing. In conclusion, only six proteins clearly related to the functional eyespot apparatus have been identified so far at the molecular level. Therefore, in this study, we intended to purify the eyespot apparatus in its entire complexity (i.e., the eyespot globules along with the specialized areas of the plasma membrane, chloroplast envelope, and thylakoid membranes; Figures 1B and 1C) to obtain a complete set of proteins from this complex cell organelle by a proteomic approach, although some loss of soluble proteins cannot be ruled out.

Table 1.

Functional Categorization and Characterization of Identified Proteins from the Eyespot Apparatus

| Gene Model (JGI Version 2)/Protein ID (JGI Version 3) or cpa | No. of Different Peptides | Function and/or Homologies of Depicted Proteins Determined by NCBI BLASTp | TMDsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins important for eyespot development | |||

| C_490073c/188648 | 10 | EYE2, no eyespot | + |

| C_630002c/156645 | 7 | MIN1, mini-eyespot | + |

| Photoreceptors | |||

| C_500071c/95849 | 8 | COP3/CHOP1/CSRA/Acop1; retinal binding protein | + |

| C_3230005c/164843d | 5 | COP1 and COP2; retinal binding protein | − |

| C_390092c/182032 | 3 | COP4/CHOP2/CSRB/Acop2; retinal binding protein | + |

| C_120056/183965 | 3 | PHOT; blue light photoreceptor | − |

| Phosphatasese | |||

| C_760036/193906f | 37 | Protein with PP2Cc (Ser-Thr phosphatases) domain | (+) |

| C_760032/178366g | 22 | Protein with PP2Cc (Ser-Thr phosphatases) domain | (+) |

| Kinasese | |||

| C_60149/131695 | 12 | Cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase II | − |

| C_230061/113847g | 10 | Similar to proteins with AarF (predicted unusual protein kinase) domain | (+) |

| C_110160/192323d | 3 | Similar to proteins with AarF (predicted unusual protein kinase) domain | (+) |

| C_70149/137286 | 2 | CK1 | − |

| Calcium-sensing and binding proteins | |||

| C_1010018/194676 | 8 | Calcium sensing receptor | (+) |

| C_20012/186813 | 5 | Protein with EF-hand, calcium binding motifh | (+) |

| C_280062/183554 | 4 | Protein with EF-hand, calcium binding motif | + |

| C_20380/111945f | 2 | Protein with EF-hand, calcium binding motif | + |

| C_40075/189454f | 2 | Protein with FRQ1 (Ca2+ binding protein) domainh | (+) |

| Putative chemotaxis-related proteins | |||

| C_1250029/189928 | 5 | Similar to MCP (Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102)h | (+) |

| C_390049/133829 | 4 | Similar to UbiE/Coq5 methyltransferases | − |

| C_290078/149419 | 3 | Putative methlytransferase (Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1) | − |

| Channels | |||

| C_280032/146232 | 8 | Similar to voltage-dependent anion channel protein | (+) |

| C_2200010/127172 | 6 | Porin-like protein | (+) |

| Retinal biosynthesis and retina-related proteins | |||

| C_970031/153728d | 14 | Similar to SOUL heme-binding proteins | − |

| C_80229/174292g | 12 | Similar to cyanobacterial retinal pigment epithelial membrane protein and lignostilbene-α,β-dioxygenase | (+) |

| C_2440006/191453f | 2 | Similar to retinol dehydrogenase 13 (all-trans and 9-cis) | (+) |

| Membrane-associated/structural proteins | |||

| Proteins with PAP-fibrillin domain | |||

| C_500037/121152g | 16 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domain | (+) |

| C_2690006/176214g | 12 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domainh | (+) |

| C_30242i | 8 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domain | − |

| C_500033/193429g | 7 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domain | (+) |

| C_250022/190008 | 4 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domain | − |

| C_2460003/154241 | 3 | Similar to harpin binding protein 1 | (+) |

| C_370103/169629d | 3 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domain | (+) |

| C_13870001/176214g | 2 | Protein with PAP-fibrillin domainh | (+) |

| Others | |||

| C_840016/154677 | 3 | Similar to algal-cell adhesin molecule, contains two FAS1 domains | (+) |

| C_190173i | 2 | Similar to Morn repeat protein 1 | (+) |

| Carotenoid and chlorophyll biosynthesis | |||

| C_1950004/194594f | 16 | DXS, 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase | (+) |

| C_230123/113656d | 7 | Cyanobacterial ζ-carotene desaturase-like protein | − |

| C_1330031/195952 | 6 | DVR, 3,8-divinyl protochlorophyllide a 8-vinyl reductase | − |

| C_180047/136810 | 4 | GGR, geranylgeranyl reductase | − |

| C_280053/136589 | 4 | POR, protochlorophyllide reductase | (+) |

| C_490019/78128 | 2 | PDS, phytoene desaturase | + |

| C_330078/191043d | 2 | PPX, protoporphyrinogen oxidase precursor | (+) |

| Lipid metabolism | |||

| C_570065/77062 | 13 | Betaine lipid synthase, extraplastidic | (+) |

| C_6260003/113915j | 3 | Similar to long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases 2 (Arabidopsis) | − |

| C_2030015/98450f | 3 | Similar to proteins with PlsC domain (1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase) | + |

| C_280073i | 3 | Similar to proteins with a diacylglycerol acyltransferase domain | (+) |

| C_220002/119132d | 3 | Similar to cyclopropane fatty acid synthases | − |

| C_7940001/113915j | 2 | Similar to a putative acyl-CoA synthetase (Oryza sativa) | − |

| C_100060/116066d | 2 | Similar to 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase (Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413) | − |

| Chloroplast ATP synthase | |||

| Cp genome | 21 | CF1 ATP synthase β-subunit | (+) |

| Cp genome | 20 | CF1 ATP synthase α-subunit | − |

| C_17110002k | 14 | CF1 ATP synthase, α-subunit | − |

| Cp genome | 8 | CF0 ATP synthase subunit I | + |

| C_200074/134235 | 7 | CF1 ATP synthase, γ-chain | − |

| C_1610012/132678d | 5 | CF1 ATP synthase, δ-chain | − |

| C_28050002k | 4 | CF1 ATP synthase ɛ-subunit | − |

| Cp genome | 4 | CF1 ATP synthase ɛ-subunit | − |

| C_480050k/105641k | 2 | CF1 ATP synthase, β-subunit | (+) |

| Cp genome | 2 | CF0 ATP synthase subunit IV | + |

| Photosystem II and related proteins | |||

| C_880018/148057d | 10 | PSBP oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 2 (23-kD subunit of oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II) | (+) |

| Cp genome | 9 | Photosystem II P680 chlorophyll A apoprotein | + |

| C_940002/130316 | 7 | PSBO oxygen-evolving enhancer protein 1 (33-kD subunit of oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II) | (+) |

| C_32080002k | 6 | Photosystem II P680 chlorophyll A apoprotein | + |

| Cp genome | 6 | Photosystem II 44-kD reaction center protein | + |

| C_1340006/153656d | 5 | PsbQ, oxygen evolving enhancer protein 3 | (+) |

| Cp genome | 4 | Photosystem II reaction center protein D2 | + |

| Cp genome | 3 | Photosystem II reaction center protein D1 | + |

| C_270022/112806f | 3 | HCF136, photosystem II stability/assembly factor | (+) |

| C_180041/190151 | 2 | Putative lumen protein, related to OEE3, PsbQ | + |

| C_770034/193552 | 2 | Lhc-like protein Lhl3 | (+) |

| Cp genome | 2 | Photosystem II reaction center protein H | + |

| LHCII proteins | |||

| C_10030/184810 | 7 | Lhcb4, minor chlorophyll a/b binding protein of photosystem II | (+) |

| C_530002/130414 | 6 | Lhcb5, minor chlorophyll a/b binding protein of photosystem II | (+) |

| C_110177/131156 | 4 | LhcbM5, chlorophyll a/b binding protein of LHCII | (+) |

| C_1460005/138110 | 4 | LhcbM9, chlorophyll a/b binding protein of LHCII | (+) |

| C_70041/184070 | 3 | LhcbM7, chlorophyll a/b binding protein of LHCII | (+) |

| C_1190021/178631d | 3 | LhcbM1, chlorophyll a/b binding protein of LHCII | (+) |

| C_2050001/186064 | 2 | LhcbM3, chlorophyll a/b binding protein of LHCII | (+) |

| Cytochrome b6f complex and plastocyanin | |||

| Cp genome | 17 | Cytochrome f | + |

| C_1090006/185971 | 7 | PETO, cytochrome b6f–associated phosphoprotein | (+) |

| C_20090002k | 4 | Cytochrome b6 | + |

| Cp genome | 4 | Cytochrome b6 | + |

| C_1580045/108310f | 2 | Plastocyanin | (+) |

| Photosystem I and related proteins | |||

| C_100097/136252 | 12 | Crd1, copper response defect 1 protein | − |

| C_1940014/130914 | 5 | PSAF, photosystem I reaction center subunit III | (+) |

| C_300013/120177 | 5 | PSAD, photosystem I reaction center subunit II | − |

| C_450050/182959 | 3 | PSAH, photosystem I reaction center subunit VI | (+) |

| C_490082/128002 | 3 | Cth1, copper target homolog 1 protein | − |

| C_1220023/165418 | 2 | PSAG, photosystem I reaction center subunit V | (+) |

| C_50019/133651 | 2 | PSAN, photosystem I reaction centre subunit N | + |

| Cp genome | 2 | Photosystem I assembly protein ycf4 | + |

| Cp genome | 2 | Photosystem I P700 chlorophyll A apoprotein A2 | + |

| LHCI proteins | |||

| C_270001/134203 | 7 | Lhca8, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | (+) |

| C_100004/78552 | 6 | Lhca7, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | (+) |

| C_1460019/174723 | 4 | Lhca1, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | − |

| C_1610027/153678 | 4 | Lhca3, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | (+) |

| C_490067/183029 | 4 | Lhca2, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | (+) |

| C_130138/133575 | 2 | Lhca5, light-harvesting protein of photosystem I | − |

| Ferredoxin and thioredoxin-related proteins | |||

| C_680071/182093 | 3 | Related to 2Fe2S ferredoxin | − |

| C_200197/142363 | 2 | PRX1 2-cys peroxiredoxin, chloroplast | − |

| Protein translocation, assembly and chaperones, chloroplast | |||

| C_750041/126835 | 14 | Heat Shock Protein 70B | − |

| C_390061/133800 | 7 | Protein disulfide isomerase 1, RB60 | (+) |

| C_270042/187077d | 6 | Similar to Tic62 | (+) |

| C_10066/173082d | 4 | Similar to Tic22 | − |

| C_10196/187295d | 3 | Albino 3-like protein | (+) |

| C_30247/100945d | 3 | Putative peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | − |

| C_460094/143879 | 2 | Similar to TOC75 | − |

| C_1110032/172529g | 2 | Similar to TOC90 | − |

| C_490015/55286d | 2 | Chloroplast DnaJ-like protein 1 | − |

| Diverse chloroplast envelope proteins | |||

| C_320089/143003 | 3 | Similar to putative chloroplast inner envelope protein (O. sativa) | − |

| C_2350003/195230 | 2 | Plastidic ATP/ADP transporter | + |

| Stromal proteins | |||

| C_280107/129019 | 9 | GapA, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A | − |

| C_30013/190455 | 5 | Malate dehydrogenase, sodium acetate induced | (+) |

| C_30202/101042f | 3 | SBPase, sedoheptulose-bisphosphatase | − |

| C_4220001/82495d | 3 | FBPase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase | − |

| C_950008/184105 | 2 | PRK, phosphoribulokinase | − |

| Proteases, peptidases, and related proteins | |||

| Chloroplast | |||

| C_1620016/114776d | 12 | FtsH protease 1, probably chloroplast targeted | + |

| C_10225/175878f | 6 | FtsH protease 2, probable ortholog of Arabidopsis FtsH2 | + |

| C_100122/101349f | 5 | Putative chloroplast thylakoidal processing peptidase | (+) |

| C_4010001/140380d | 2 | Similar to ClpC or ClpD chaperone, Hsp100 family, ATP-dependent subunit of Clp protease | − |

| Others | |||

| C_240088/116429g | 7 | Similar to metalloendopeptidases | (+) |

| Cytosolic proteins | |||

| C_1340012/185673 | 6 | HSP70a, Heat Shock Protein 70 α, light and heat inducible | (+) |

| C_550067/158129d | 4 | MDH, cytosolic malate dehydrogenase | + |

| C_1460023/191668d | 3 | Isocitrate lyase, cytosolic or peroxisomal | − |

| C_970001/107783d | 2 | Similar to expressed protein with saccharopine dehydrogenase domain | (+) |

| Mitochondrial | |||

| C_710028/192142 | 11 | ASA2, putative mitochondrial ATP syntase-associated protein | (+) |

| C_3890001/78348 | 8 | β-Subunit of mitochondrial ATP synthase | − |

| C_730039/138185 | 6 | ANT1, mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocator protein | + |

| C_420010/78831 | 5 | ASA1, ATP syntase-associated protein 1 (P60 or MASAP) | − |

| C_230150/182740 | 5 | ASA4, putative mitochondrial ATP syntase-associated protein | − |

| C_490077/100068 | 4 | Putative mitochondrial processing peptidase α-subunit | (+) |

| C_1540001/159938 | 3 | Hypothetical mitochondrial carrier protein | (+) |

| C_530055/191516 | 3 | Putative mitochondrial dicarboxylate transporter | + |

| C_20064/76602 | 2 | α-Subunit of the mitochondrial ATP synthase | (+) |

| C_710036/192157 | 2 | NUOP6, mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase 19-kD subunit precursor | − |

| C_90043/195712d | 2 | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIb/COX12 | − |

| C_750022/152682 | 2 | ASA3, putative mitochondrial ATP syntase-associated protein | − |

| C_1380005/194183 | 2 | ATPase, γ-subunit, probably mitochondria targeted | − |

| C_260140/111351d | 2 | Mitochondrial import receptor subunit Tom40-like | − |

| Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum/vesicle trafficking | |||

| C_490107/94234d | 4 | Similar to Golgi apparatus protein 1 isoform 2 (Canis familiaris) | + |

| C_50001/133859 | 3 | Heat Shock Protein 70, endoplasmic reticulum isoform | + |

| C_250128/78954 | 2 | Calreticulin | (+) |

| C_290072/118846f | 2 | CYN20-1, peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (rotamase), cyclophilin type | + |

| C_490065/144604 | 2 | Putative peptidase | + |

| C_10830001/186126 | 2 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein | − |

| Cytoskeleton | |||

| C_1320004/186023 | 2 | TUA2, α tubulin 2 | (+) |

| Ribosomes, translation, and DNA-related | |||

| C_2390008/195598d | 5 | RPL4, cytosolic ribosomal protein L4 | (+) |

| C_1060035/160406 | 3 | Histone H2A | − |

| C_290113/104082f | 3 | Similar to histone-like bacterial DNA binding protein; possible targeting to organelle | − |

| C_2370012/195131d | 3 | RPL22, cytosolic ribosomal protein L22 | − |

| C_380026/105289f | 3 | RPL7a, cytosolic ribosomal protein L7a | − |

| C_930034/168484 | 3 | RPS3a, cytosolic ribosomal protein S3a | − |

| C_430028/105734f | 3 | RACK1, component of cytosolic 40S subunit | − |

| C_870056/145271 | 3 | RPL14, cytosolic ribosomal protein L14 | − |

| Cp genome | 3 | Chloroplast RNA polymerase β-subunit | − |

| C_3470003/24289 | 2 | RPS15, cytosolic ribosomal protein S15 | − |

| C_1060004l | 2 | HFO8/HFO22, histone H4 | − |

| C_3320003/129809 | 2 | RPL13, cytosolic ribosomal protein L13 | − |

| C_130042/126059 | 2 | RPSa, cytosolic ribosomal protein Sa | − |

| C_1060006/123665 | 2 | HTR5, histone H3 | − |

| C_3670002/174711g | 2 | RPL23a, cytosolic ribosomal protein L23a | (+) |

| C_380137/162845 | 2 | RPL13a, cytosolic ribosomal protein L13a | − |

| C_1480038/143072 | 2 | RPS24, cytosolic ribosomal protein S24 | − |

| C_480013/24344 | 2 | RPS14, cytosolic ribosomal protein S14 | − |

| C_90190/188837g | 2 | RPS4A, cytosolic ribosomal protein S4E | − |

| Others | |||

| C_540038/184617 | 8 | Similar to zonadhesin (Mus musculus) | − |

| C_410057/116285f | 8 | Similar to MGC86418 protein (Xenopus laevis); FAD_Synth, Riboflavin kinase/FAD synthetase domains | − |

| C_1400008/152568 | 8 | Similar to UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase-like proteins | (+) |

| C_80056/184328 | 5 | Similar to chitinase, contains two LysM domains | + |

| C_190016/122660d | 2 | Similar to aldo-keto reductase/oxidoreductase (Arabidopsis) | (+) |

| C_950022/103066f | 2 | Similar to riboflavin biosynthesis-related protein (Arabidopsis); RibD, pyrimidine deaminase (coenzyme metabolism) domain | − |

| C_1040013/132437 | 2 | Similar to putative NADPH-dependent reductase (O. sativa japonica cultivar group) | (+) |

| C_1330014/146801 | 2 | Similar to formate acetyltransferase (Thermosynechococcus elongatus BP-1); PFL1, pyruvate formate lyase domain | − |

| C_1490014/122298d | 2 | Similar to amidophosphoribosyl transferase (Ralstonia metallidurans CH34); PurF domain | − |

| C_1690020/99287, 113924, 54929m | 2 | Similar to adenylosuccinate lyase (Pseudomonas syringae pv Phaseolicola) | − |

| C_4220002/153473 | 2 | Similar to amidophosphoribosyl transferase (Silicibacter sp TM1040); Gln amidotransferases class-II (GN-AT) GPAT-type domain | − |

| C_2020016/154307 | 2 | Similar to methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate-homocysteine methyltransferase (Met synthase, vitamin B12-independent isozyme) | (+) |

| Conserved proteins of yet unknown function | |||

| C_1670026/121991g | 11 | Similar to conserved plant/cyanobacterial proteins of unknown functions, contains two DUF1350 domains | (+) |

| Cp genome | 7 | Hypothetical protein ChreCp059 | + |

| C_350047/183568d | 6 | Similar to conserved hypothetical protein (Prochlorococcus marinus strain NATL2A) | − |

| C_1550001/145347 | 6 | Similar to hypothetical protein TeryDRAFT_4244 (Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101) | − |

| C_1580021/60278 | 5 | Similar to DUF477 domain containing proteins | + |

| C_140123/160137d | 5 | Similar to DUF393 domain containing protein of unknown function (Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501) contains to two CBS domains | (+) |

| C_50005i | 4 | Conserved uncharacterized protein, FAP 24 (found in flagella proteome) | − |

| C_540056/191988 | 4 | Conserved plant protein of unknown function | − |

| C_120189/183944d | 3 | Weakly similar to conserved plant/cyanobacterial proteins | − |

| C_630005/114879d | 3 | Similar to conserved plant/cynanobacterial proteins | − |

| C_740067/194163g | 3 | Weakly similar to possible signaling protein TraB (Halobacterium sp NRC-1) | + |

| C_420064/183448 | 2 | Similar to conserved plant proteins | + |

| C_330033l | 2 | Similar to DUF901 domain containing proteins | (+) |

| Novel proteins of unknown function | |||

| C_110103/95493f | 13 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_1010035/194644 | 7 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | + |

| C_580038/158327d | 7 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | − |

| C_290134/149502 | 5 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_10188/192448d | 4 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | − |

| C_100162i | 3 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | + |

| C_330108/191022d | 3 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp, FAP 102 (found in flagellar proteome) | (+) |

| C_910050/157545d | 3 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_820024/189359 | 3 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_1270018/187882 | 3 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | − |

| C_10105l | 2 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_200025/167270g | 2 | No significant hits in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_17370001/178366g | 2 | No significant hits in NCBI BLASTp | − |

| C_1670008/178671g | 2 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_210162/182705 | 2 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | + |

| C_140087/152606 | 2 | No significant hit in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

| C_1130009/190685g | 2 | No significant hits in NCBI BLASTp | (+) |

cp, chloroplast; JGI, Joint Genome Institute.

Predictions done with TMHMM, TMpred, and TopPred. +, TMDs predicted by all three programs; (+), TMDs predicted by two programs; −, TMDs predicted by only one or no program.

Known or predicted eyespot apparatus-related proteins.

Version 3 gene model differs from gene model version 2; full or partial EST support for gene models of versions 2 and 3.

Kinases and phosphatases that are putative signaling related.

Version 3 gene model differs from gene model version 2; full or partial EST support for gene model version 2.

Version 3 gene model differs from gene model version 2; no EST support for both genome versions.

As E-value limit 1e-05 was set; in a few cases of special functional implications, E-values below are listed, and those have been marked.

No gene model in version 3; full or partial EST support for gene model version 2.

Two version 2 models were fused to one version 3 model.

Proteins that appear in gene models and at the same time in the chloroplast genome, most likely due to contaminations of the genomic DNA with chloroplast DNA.

No gene model in version 3; no EST support for gene model version 2.

Version 2 gene model has been split in more than one gene model in version 3; few peptides are split also, EST support for versions 2 and 3. Minor changes (e.g., only a few amino acids) in gene model version 3 compared with gene model version 2 are not specified.

Notably, tactic (photo- and chemo-) movements in C. reinhardtii are not only controlled by light but also by the circadian clock (Bruce, 1970; Mergenhagen, 1984; Byrne et al., 1992). Both the rhythms of phototaxis and chemotaxis can be entrained by an LD cycle and continue under constant conditions of light (or darkness) and temperature with a period of ∼24 h. While circadian phototaxis peaks during subjective day (Bruce, 1970; Mergenhagen, 1984), the chemotactic response to ammonium reaches its maximum during subjective night (Byrne et al., 1992). Since the phase of circadian phototaxis can be reset by both red and blue light (Johnson et al., 1991; Kondo et al., 1991), an involvement of different photoreceptors in affecting circadian rhythms is apparent. It can be expected that the eyespot apparatus is involved in the entrainment of the endogenous clock via photoreceptors and a connected signaling cascade, and it might even contain key components of the endogenous oscillator itself. In all eukaryotic model organisms studied so far, including Neurospora crassa, Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster, mice, and humans, phosphorylation plays a key regulatory role within the circadian oscillator. Crucial components of the endogenous oscillator that are regulated via positive and negative feedback loops are progressively phosphorylated, which supports their interaction with other proteins, promotes their nuclear entry, and finally leads to their degradation at a specific stage of the circadian cycle (reviewed in Dunlap, 1999; Harmer et al., 2001; Panda et al., 2002; Reppert and Weaver, 2002; Dunlap and Loros, 2004). While the essential components of the circadian oscillator in the above-mentioned model organisms are not conserved in C. reinhardtii, the involved Ser-Thr kinases (casein kinase 1 [CK1], CK2, and SHAGGY) and the Ser-Thr protein phosphatases (PP2A and PP1) are highly conserved (Mittag et al., 2005). Therefore, appearance of any of these proteins within the eyespot proteome will be indicative of their potential function toward circadian regulation of tactic movements.

Proteomics, which often involves gel electrophoresis, nano-liquid chromatography in combination with electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS), and bioinformatic analysis, has become a powerful tool for the investigation of proteins (Reinders et al., 2004). In plant model organisms like C. reinhardtii and Arabidopsis, several large-scale proteome analyses have been performed in recent years, resulting in the characterization of cellular subfractions such as cilia (Pazour et al., 2005), centrioles (Keller et al., 2005), the vegetative vacuole (Carter et al., 2004), specific chloroplast subproteomes (Peltier et al., 2002; Yamaguchi et al., 2002; Majeran et al., 2005), or the phosphoproteome (Wagner et al., 2006). In this study, we have characterized the proteome of the eyespot apparatus from C. reinhardtii by 1365 peptides belonging to 583 different proteins. In total, 202 proteins were identified via at least two peptides. Here, we describe a detailed analysis of these 202 proteins, including their possible roles in eyespot structure, development, specific metabolic processes, and in tactic (photo- and chemo-) signaling pathways. A functional analysis was performed with one of them, CK1. Our results suggest that it is a major player in several processes, including hatching, flagellum formation, and circadian control of phototactic behavior.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation and Characterization of a Fraction Enriched in Eyespot Apparatuses

One major objective of this study was to yield a strongly enriched eyespot fraction to gain a rather complete proteome of this cell organelle and to minimize contaminating proteins. Due to its complex ultrastructure involving local specializations of different compartments (Figures 1B and 1C), biochemical isolation of the eyespot apparatus is a challenging task. Taking advantage of a previously described method for the isolation of eyespot globules from the green alga Spermatozopsis similis (Renninger et al., 2001), we developed a procedure for the purification of the C. reinhardtii eyespot apparatus that is based on flotation on successive sucrose gradients (see Methods).

As a first visual marker for enrichment of eyespot apparatuses during the purification procedure, we took the striking orange-red color of the eyespot globules (Figure 1A). A deep orange-red fraction was separated from a weak yellow-orange fraction, the bulk of chloroplasts, and cell debris by the first gradient centrifugation step (Figure 1D). This carotenoid-rich fraction was then purified by two additional gradient centrifugation steps to minimize contamination by other cell organelles, thylakoids, and soluble proteins and finally concentrated by a floating centrifugation step (Figure 1D).

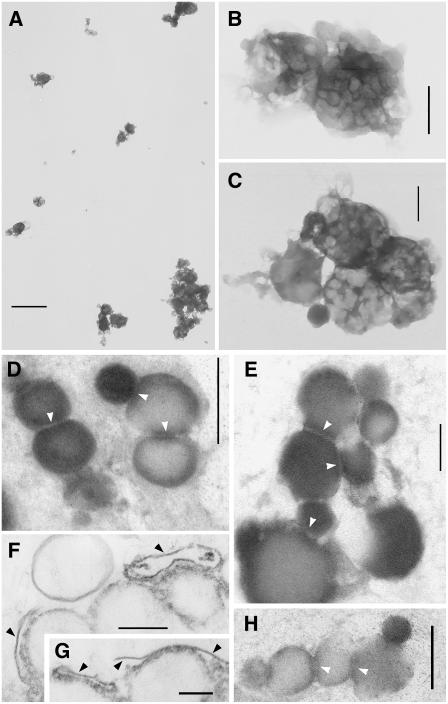

To verify enrichment of eyespot apparatuses and judge their purity, the final fractions of three independent isolations were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (Figure 2). Whole-mount preparations revealed enrichment of globule aggregates overlaid by membrane patches of varying size, which had a strong tendency to form larger aggregates (Figures 2A to 2C). A significant number of isolated single globules were not observed. The average diameter of the individual globule aggregates (0.66 μm) was similar to that of the eyespot apparatus of C. reinhardtii in situ (0.65 μm; Kreimer, 2001; Dieckmann, 2003). Thin sections confirmed the successful isolation of fragments of eyespot apparatuses, (i.e., globules associated with varying layers of membranes; Figures 2D to 2H). The close association and arrangement of these membrane patches with the eyespot globules strongly suggests that they represent those parts of the plasma membrane, the two chloroplast envelope membranes as well as the thylakoid system that form, in conjunction with the eyespot globules, the functional green algal eyespot apparatus (Figures 1B and 1C; Foster and Smyth, 1980; Melkonian and Robenek, 1984; Kreimer, 1994). The structural preservation of the isolated eyespot fragments varied. Although often close packing of the eyespot globules was preserved and the diameter of many globules matched the in vivo range of 80 to 130 nm (Kreimer, 2001), many globules appeared to be fused during the isolation procedure and preparation for electron microscopy (diameters > 250 nm). Except the small amounts of membrane patches that were not associated with eyespot globules (Figure 2A), no contaminations (e.g., by cell debris, intact cell organelles, or flagella) were evident.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the Final Fraction Enriched in Eyespot Apparatus Fragments by Transmission Electron Microscopy.

(A) to (C) Whole-mount preparations. Overview (A); details ([B] and [C]). Note that the eyespot fragments tend to aggregate. Bars = 2500 nm (A) and 400 nm ([B] and [C]).

(D) to (H) Thin sections. White arrow heads indicate the contact sites between the eyespot globules. Black arrowheads indicate eyespot membranes, partially associated with fuzzy fibrilar material typically observed in situ between the plasma membrane and chloroplast envelope in the region of the eyespot apparatus. Bars = 250 nm ([D], [E], [G], [H], and [F]) and 150 nm (F).

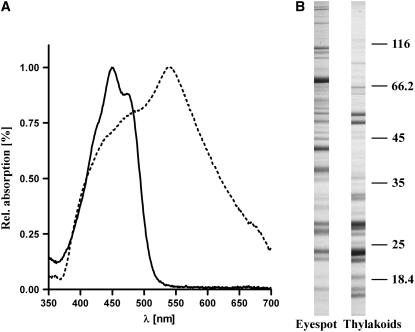

Spectral analysis of the pigments that are present in the eyespot fraction was performed to verify that carotenoids were present at a significantly higher rate in comparison with chlorophyll, which is solely present within the thylakoid membranes (Figure 1B). In aqueous solution, the main absorption peak was observed in the yellow region of the spectrum (539.8 nm ± 1.7 nm; Figure 3A). It coincides well with the peak observed for in vivo eyespot reflectivity in C. reinhardtii (540 to 550 nm; Schaller and Uhl, 1997). In acetone extracts, a typical carotenoid spectrum with major absorption peaks at 449.5 nm ± 0.6 nm and 474.5 nm ± 1.3 nm was observed. Only a rather small chlorophyll peak at 680 nm was detectable (Figure 3A). The carotenoid:chlorophyll ratio (absorbance 478 nm:680 nm) ranged between 60 and 70 in different preparations (Figure 3A). A comparison of the amount of chlorophyll present in the crude extract with the amount of chlorophyll that could be found in the final eyespot fraction revealed that <0.0005% of the chlorophyll remained there. These data indicate that the applied purification strategy has effectively removed thylakoids that are not directly associated with the eyespot apparatus. In addition, comparative SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins from the eyespot fraction and isolated thylakoids corroborates this conclusion. The protein pattern observed for the eyespot fraction clearly differed from that of isolated thylakoids and revealed enrichment of proteins that cannot be found among the thylakoid proteins (Figure 3B). The yielded protein pattern of the eyespot fraction was highly reproducible in five independent purifications, and only for a few proteins were variations in their relative abundances evident (see Supplemental Figure 1A online).

Figure 3.

Spectral Analysis and SDS-PAGE Analysis Demonstrates That Thylakoids Are Not Dominant in the Fraction of Eyespot Fragments.

(A) Normalized absorption spectra of the final fraction in aqueous solution (dashed line) and in 90% acetone (solid line).

(B) Comparison of the protein pattern of the eyespot fraction and isolated thylakoids. Proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated on the right (in kilodaltons).

In summary, we conclude that eyespot apparatuses were strongly enriched in the final gradient fraction and that their possible contamination by other cell organelles and soluble proteins was largely reduced. It was shown with freeze fracturing that green algal eyespot apparatuses have a high intramembrane particle density in the plasma membrane and the outer chloroplast envelope (Melkonian and Robenek, 1984) and that proteins are associated with the carotenoid-rich eyespot globules (Renninger et al., 2001, 2006). Thus, specific enrichment of proteins intrinsic to this complex cell organelle can be expected in the purified fraction. In this study, we intended to purify the eyespot apparatus in its entire complexity along with the specialized areas of the plasma membrane, chloroplast envelope, and thylakoid system belonging to the functional eyespot apparatus. However, complete separation of these specialized membrane areas of the eyespot from the nonspecialized parts of these membrane systems cannot be achieved by biochemical methods. Thus, we cannot rule out that a small portion of membrane extensions is still present in the final fraction. Additionally, only a few free membrane patches not associated with the eyespot fragments were observed in the electron microscopy analysis. Thereby, normal constituents of such membranes and, to a lesser degree, also from the stromal and cytosolic compartments could be present among the proteins associated with this fraction.

Proteome Analysis of the Eyespot Apparatus

General Overview

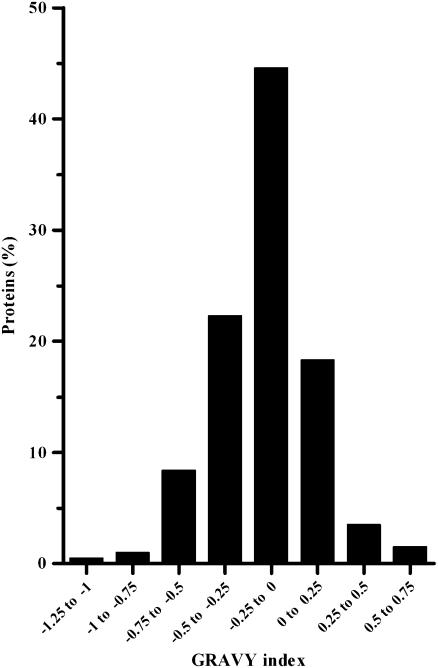

To identify individual proteins of the enriched eyespot fraction by MS/MS, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and the gel was sliced into 54 pieces (see Supplemental Figure 1B online). Proteins from half of each slice were in-gel digested with trypsin. The generated peptide fragments were subjected to nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses using a linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Table 1 summarizes the identified proteins (202 in total) along with the number of different peptides that were found within a given protein, their biological function (if known), and the presence of predicted transmembrane domains (TMDs). Only proteins are listed where at least two different peptides fulfilling the criteria for the Xcorr, the probability score, and the dCN values (see Methods) could be identified by peptide MS/MS using SEQUEST-based Bioworks software (version 3.2) along with Chlamydomonas databases. From the 202 proteins identified with high confidence, 72 proteins were identified by five or more different peptides and 130 proteins by two to four different peptides (Table 1). All different peptides (984 in total) from these proteins are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online along with the charges of the peptides, their Xcorr values, and the GRAVY index of the proteins. The frequency distribution of the GRAVY index (Figure 4) indicates enrichment of proteins with a more hydrophobic character in the eyespot fraction. Similar GRAVY frequency distributions have been reported for typical membrane proteomes (e.g., the Arabidopsis plasma membrane and subfractions of the thylakoid membrane; Friso et al., 2004; Marmagne et al., 2004). Also, the TMD predictions for the 202 proteins corroborate enrichment of proteins with a hydrophobic character. Thirty-nine proteins (19.3%) were predicted to contain TMDs by all three used programs (see Methods; Table 1), and for another 80 proteins (39.6%), two programs predicted their presence (i.e., these proteins have at least a partial hydrophobic character). The enrichment of proteins with a moderate hydrophobic and amphiphatic character correlates well with the ultrastructure of the green algal eyespot apparatus, which is dominated by hydrophobic structures.

Figure 4.

The Majority of the Proteins from the Eyespot Proteome Have a More Hydrophobic Character.

Frequency distribution of the GRAVY index of the proteins identified with at least two peptides in the fraction enriched in eyespot apparatuses.

All six currently known or predicted proteins from C. reinhardtii related to the eyespot apparatus (for detailed discussion, see section on known/predicted eyespot proteins and retinal-related proteins) are among the identified proteins, indicating that the presented proteome data might enclose a rather complete list. Furthermore, with the exception of one of the retinal-based photoreceptors (COP4; three different peptides), these proteins were represented with 5 to 10 different peptides. As the number of peptides identified in complex mixtures by ESI-MS/MS can roughly correlate with the abundance and size of proteins (Washburn et al., 2001), this further supports our conclusion that eyespot proteins are indeed well enriched in the analyzed fraction. However, we cannot rule out that some of the soluble eyespot-related proteins might have been lost during the purification procedure. As expected, a significant proportion of proteins (at least 36%) also represent proteins of thylakoids and chloroplast envelope membranes, which are part of the eyespot apparatus (Figures 1B and 1C). These include, for example, many of the thylakoid membrane–associated proteins of photosystems I and II along with its light-harvesting proteins and the ATPase complex, proteins responsible for translocation over the two chloroplast envelope membrane or plastidic chaperones. By contrast, only a few cytosolic and stromal proteins involved in primary carbon metabolism were identified. Notably, the dominating ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase was not detected. Thirty proteins (14.9%) in the eyespot fraction represented novel and conserved proteins of as yet unknown function. Additionally, the list of proteins identified by two or more peptides was enriched in proteins potentially involved in signaling (9.9%), proteins possessing plastid lipid-associated protein (PAP)-fibrillin domains (4%), and in proteins involved in pigment biosynthesis (4.5%) and lipid metabolism (3.5%). The latter two include also rather specialized enzymes of such pathways. These will be discussed in detail later. Only one protein of the cytoskeleton, α-tubulin, was identified with two peptides. Major contaminants appear to come from cytosolic ribosomes and DNA-related proteins (8.4%), mitochondria (6.9%), and the Golgi/endoplasmic reticulum/vesicle trafficking machinery (3%). Proteins belonging to the latter two groups probably arise from free membrane patches that were not associated with the eyespot fragments, as mentioned before. These values are in the contamination range reported for proteome analysis of other cell organelles rather subtle in isolation, for example, the vegetative vacuole of Arabidopsis (Carter et al., 2004) or the basal bodies of C. reinhardtii (Keller et al., 2005).

An additional 381 proteins were identified by only one peptide (see Supplemental Table 2 online). This group of proteins was not subjected to an in-depth analysis. It contains likely contaminants and small and/or very low abundance proteins possibly related with the eyespot apparatus.

Known/Predicted Eyespot Proteins and Retinal-Related Proteins

As already mentioned, our data set contains all currently known or predicted proteins related to the eyespot apparatus. Besides the two retinal-based photoreceptors, COP3 and COP4 (eight and three different peptides, respectively), that are involved in phototactic and photophobic responses (Nagel et al., 2002, 2003; Sineshchekov et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2003), both splicing variants of the abundant retinal binding protein COP (COP1 and COP2; Deininger et al., 1995; Fuhrmann et al., 2003) were identified with five peptides. Both proteins seem not to be involved in behavioral responses, and their function is still unclear (Fuhrmann et al., 2001). Localization of COP1/2 and COP3 to the eyespot apparatus was previously demonstrated by immunofluorescence and/or green fluorescent protein tagging in C. reinhardtii (Deininger et al., 1995; Fuhrmann et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2003). The theoretical postulated additional photoreceptors that show sequence homology to conserved domains of COP1-4 (Kateriya et al., 2004) were, however, not found in our data set. EYE2 and MIN1, two proteins important for eyespot formation and size control (Lamb et al., 1999; Roberts et al., 2001; Dieckmann, 2003), were identified with 7 and 10 peptides, respectively. EYE2 has been shown by protein gel blot analysis to be enriched in a fraction of intact eyespot apparatuses from S. similis, but was not detectable in purified eyespot globules from this green alga (Dieckmann, 2003; Renninger et al., 2006). Recently, insertions alleles of two other mutants (eye3 and mlt1) that cause defects in eyespot development have been identified (Lamb et al., 1999; Dieckmann, 2003). It will be interesting to check whether these gene products will be among the identified proteins once their sequences will be known and released to public.

Beside proteins involved in the general biosynthesis pathway of carotenoids in C. reinhardtii (e.g., 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase and phytoene desaturase; Grossman et al., 2004), we also identified proteins that are possibly important for retinal biosynthesis in the eyespot proteome. One protein (C_80229) has similarities to cyanobacterial lingostilbene-α,β-dioxygenases and β-carotene-15,15′-monooxygenases. Whereas the latter enzymes are known to produce retinal from β-carotene, it has been recently shown that an enzyme from Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 annotated as lingostilbene-α,β-dioxygenase forms retinal from diverse apo-carotenoids (Ruch et al., 2005). The protein identified in the eyespot fraction has an almost identical molecular mass (54.1 kD) as the Synechocystis protein (54.3 kD) and appears to be quite abundant (12 different peptides). Another protein (C_2440006) has similarities to a retinol dehydrogenase and other members of the oxidoreductase short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family. In the visual cycle of vertebrates, these enzymes can catalyze in principle the retinol or retinal synthesis step (e.g., Palczewski and Saari, 1997). The detection of these two enzymes in the eyespot fraction indicates that at least part of retinal biosynthesis might take place directly in the region of the eyespot apparatus (i.e., in close vicinity to the retinal-based photoreceptors).

A third protein (C_970031) with similarities to the SOUL/HBP family of proteins was detected with 14 peptides in the eyespot proteome. In vertebrates, the SOUL protein is specifically expressed in the retina and pineal gland. However, its physiological role in the eye is not known (Zylka and Reppert, 1999; Sato et al., 2004). Members of the SOUL/HBP family have also been identified in the genomes of Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa), and other higher plants, and a SOUL domain protein is present in the plasma membrane proteome of Arabidopsis (Marmagne et al., 2004). The protein identified in the eyespot fraction has highest similarities to the SOUL-heme binding-like proteins from Arabidopsis and rice. However, functional information is not available yet in plants.

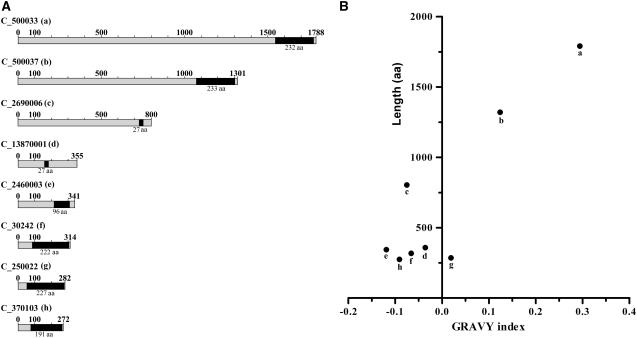

Proteins with PAP-Fibrillin Domains Are Enriched in the Eyespot Apparatus Fraction

None of the structural proteins preventing coalescence of the carotenoid-rich eyespot globules in the highly ordered eyespot globule plate are currently known. Potential candidates for such functions may belong to the fibrillin family. Fibrillin, also termed PAP, is a major protein of carotenoid-rich fibrils and plastoglobules in chromoplasts and chloroplasts and plays an important role in carotenoid sequestration (Deruère et al., 1994; Pozueta-Romero et al., 1997). Proteins belonging to the fibrillin family are characterized by the PAP-fibrillin domain (gnl|CDD|16052; pfam 04,755) and constitute a conserved group of proteins present in most plastid types. They are mainly localized at the interface between lipids and the stroma (Rey et al., 2000). Their molecular masses range typically between ∼25 and ∼45 kD. Thus, the sizes of fibrillins associated with thylakoids/plastoglobules in Arabidopsis varies between 234 and 409 amino acids, and their conserved PAP-fibrillin domain sizes range from 151 to 217 amino acids (Friso et al., 2004). In the fraction enriched in eyespot apparatuses, eight proteins with PAP-fibrillin domains were identified (Table 1). Five of these proteins fall in this size range, whereas three are significantly larger (800 to 1788 amino acids; Figure 5A). In addition, two proteins (C_2690006 and C_13870001) that have an unusual small PAP-fibrillin domain (27 amino acids) were found. Notably, all PAP-fibrillin domain containing proteins in the eyespot fraction have a hydrophobic character, but the two largest are more hydrophobic than the others (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Proteins with PAP-Fibrillin Domains Are Enriched in the Eyespot Fraction and Some Are up to Four Times Larger Than Fibrillins Associated with Higher Plant Thylakoids and Plastoglobules.

(A) Polypeptides (N to C termini) identified in our MS analysis are represented schematically. PAP-fibrillin domains that were identified by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLASTp conserved domain searches are indicated in black and their length is given below in amino acids (aa). The reduced PAP-fibrillin domains observed in C_13870001 and C_2690006 are identical.

(B) Correlation between protein length (in amino acids) and the GRAVY index for those proteins containing PAP-fibrillin domains. Letters refer to the gene model given in (A).

One function of members of the fibrillin family in higher plants is stabilization of carotenoid fibrils, plastoglobules, and thylakoids (Deruère et al., 1994; Gillet et al., 1998; Eymery and Rey, 1999; Kessler et al., 1999; Rey et al., 2000). Most notably, overexpression of fibrillin in higher plants resulted in organization of plastoglobules in clusters, whose degree appears to be correlated with the abundance of this protein. Also, fibrillin was suggested to prevent coalescence of plastoglobuli and to mediate interactions between carotenoid-rich fibrils (Deruère et al., 1994; Rey et al., 2000). Therefore, the presence of several proteins with PAP-fibrillin domains in the eyespot proteome is of special interest with regard to its structure. In the functional eyespot apparatus, the carotenoid-rich globules exhibit a close hexagonal packing and have an intimate contact to thylakoids and the chloroplast envelope. Thus, we hypothesize that some of the proteins with PAP-fibrillin domains might have functions in globule stabilization and may also be involved in interactions necessary to form the highly ordered eyespot globule layers. The presence of a specialized interface between the eyespot globules and toward the stroma is supported by thin section and freeze fracture electron microscopy, which demonstrated regularly arranged particles at the eyespot globule surface in different green algal species (Walne and Arnott, 1967; Renninger et al., 2001). In addition, biochemical evidence for the involvement of a protein scaffold in globule stabilization and globule–globule as well as globule–membrane interactions has been provided by the use of proteases (Renninger et al., 2001, 2006). However, not all proteins possessing this domain might have these functions. One of the PAP-fibrillin domain proteins identified in the eyespot proteome (C_2460003) has similarities to higher plant proteins annotated in the databases as harpin-interacting proteins. Harpins are proteins produced by bacterial plant pathogens, which elicit the complex natural defense mechanisms in plants (Wei et al., 1992) and also possess a PAP-fibrillin domain.

Beside the PAP-fibrillin domain-containing proteins, two further potential candidates for mediating membrane–membrane interactions came up in the eyespot proteome. The first is encoded by gene model C_840016 and has similarities to a cell adhesion protein from the colonial green alga Volvox carteri. In addition, this protein contains two weak fascilin I domains. These domains are present in cell adhesion molecules of vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, and bacteria. The second protein (C_190173) contains a region with similarities to an algal MORN repeat protein. The MORN repeat motif functions in attaching proteins to membranes and forming junctional complexes between membranes (Takeshima et al., 2000; Shimada et al., 2004). In the eyespot apparatus, proteins mediating membrane–membrane interactions might be involved in, for example, maintaining the close contact between the plasma membrane and the chloroplast envelope.

Ca2+ Binding Proteins, Kinases, and Phosphatases Are Present in the Eyespot Apparatus

The eyespot apparatus acquires light information via photoreceptors and forwards it through signaling pathways to the flagella. In these signaling cascades, Ca2+ is intricately involved (Witman, 1993; Pazour et al., 1995; Sineshchekov and Govorunova, 1999). Excitation of the photoreceptors in the eyespot apparatus initiates fast inward directed complex photoreceptor currents in the eyespot region, which are mainly carried by Ca2+ (Harz and Hegemann, 1991; Holland et al., 1996). COP3 and COP4 are directly light-gated channels allowing an extreme fast depolarization at high light intensities (Nagel et al., 2002, 2003). At low light intensities, however, delay of the photoreceptor currents by several milliseconds suggests involvement of a signal amplification system indirectly activating ion channel activity in the eyespot apparatus (Braun and Hegemann, 1999; Sineshchekov and Govorunova, 2001). As COP4 is mainly permeable to Ca2+ (Nagel et al., 2003), an early increase in the free concentration of Ca2+ in the narrow space between the plasma membrane and chloroplast envelope in the region of the eyespot apparatus can be expected to be involved in signaling. In accordance with the major role of Ca2+ fluxes in both photoresponses, we identified five proteins with potential roles in Ca2+ signaling in the eyespot proteome. One protein (C_1010018, eight different peptides) is annotated as a calcium sensing receptor of C. reinhardtii, and the other four proteins have Ca2+ binding domains belonging to the EF-hand superfamily (two to five different peptides). For these proteins, similarities in BLAST searches are restricted to the Ca2+ binding domains. The hydrophobic character of all five proteins favors their local restriction to membranes in the region of the eyespot apparatus. Thus, these proteins are potential candidates for spatially restricted Ca2+ signaling processes likely to occur upon stimulation of the photoreceptors. In accordance with this suggestion, these proteins are absent from the flagella, in which Ca2+ also plays a major signaling role (Witman, 1993; Pazour et al., 2005).

Changes in the free concentration of Ca2+ from 10−8 to 10−7 M have been shown to strongly affect rapid protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in isolated green algal eyespot apparatuses (Linden and Kreimer, 1995). Based on homology searches and domain analyses, four kinases and two phosphatases were identified in the eyespot proteome (Table 1), underlining the potential importance of protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in signaling processes in the eyespot apparatus. Two proteins (C_230061 and C_110160) are defined by their AarF domain as members of a group of unusual protein kinases. The other two gene models encode known protein kinases: the cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase II (C_60149) and CK1 (C_70149). In addition, the blue light photoreceptor phototropin was identified in the eyespot proteome. As a member of the phototropin family, this C. reinhardtii protein contains a Ser-Thr kinase domain (Huang et al., 2002). Interestingly, these three proteins are also localized in the flagella (Huang et al., 2004; Pazour et al., 2005), pointing to their importance for motility and possibly also tactic responses. CK1 experimental evidence for this assumption will be presented later.

Based on the high number of different peptides, it can be assumed that the two Ser-Thr phosphatases encoded by the gene models C_760036 (37 different peptides) and C_760032 (22 different peptides) are rather dominating proteins in the eyespot fraction. Both are members of the PP2C family of phosphatases. Different PP2Cs have been found as regulators of signal transduction pathways and development in plants (Schweighofer et al., 2004). Their apparent dominance may point to the need of rapid downregulation of signaling pathways initiated by protein kinases in the eyespot apparatus. This assumption would be in accordance with the recurrent theme in higher plants that PP2Cs regulate signaling negatively (Schweighofer et al., 2004). As with the Ca2+ binding proteins, their moderate hydrophobic character might allow special restriction to the region of the eyespot apparatus. These phosphatases are not present in the flagella, where massive protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is crucial for signaling and motility control (Porter and Sale, 2000; Pazour et al., 2005).

Functional characterization of these putative signaling elements may aid future research in unraveling the signaling mechanisms starting from the eyespot apparatus. However, it should be considered that some soluble and low abundance proteins might be missing in the list of putative signaling proteins present in this complex cell organelle.

Possible Chemotaxis-Related Proteins in the Eyespot Apparatus

C. reinhardtii exhibits chemotactic responses to various substances. Its sensitivity to chemical stimuli is tightly related to its life cycle and is controlled by blue light. Phototropin has been shown to control multiple steps in the sexual life cycle of C. reinhardtii and to play a crucial role in mediating changes in chemotaxis during the initial phase of the sexual life cycle (Huang and Beck, 2003; Ermilova et al., 2004; Govorunova and Sineshchekov, 2005). As already mentioned, it is present in the eyespot proteome. In addition, chemical stimuli interfere with the inward photoreceptor currents, the earliest detectable events in the signal transduction chain of the photoresponses, pointing to a possible integration of photosensory and chemosensory signaling pathways at their initial steps (Govorunova and Sineshchekov, 2003, 2005). In this context, the detection of a protein with similarities to a cyanobacterial methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein (MCP) in the eyespot proteome is of special interest. MCPs are the receptor proteins in bacterial chemotaxis (Szurmant and Ordal, 2004). The protein, encoded by gene model C_1250029, is completely covered by ESTs and exhibits a weak similarity to a MCP of Nostoc. It was identified by five different peptides in our analysis. Its molecular mass (18.8 kD) is slightly larger than that of the Nostoc protein (11.7 kD). Of the 107 aligned amino acids, 44.9% are identical and 21.5% are in addition functionally conserved between both proteins. Notably, two proteins (C_290078 and C_390049) with similarities to cyanobacterial methyltransferases (three and four different peptides, respectively) also were identified along with the MCP-like protein in the eyespot fraction. In bacterial chemotaxis, methylation and demethylation of MCPs is important for sensory adaptation and provide a memory mechanism in chemotaxis (Webre et al., 2003; Szurmant and Ordal, 2004). However, the involvement of these proteins in chemosensory signaling of C. reinhardtii remains to be demonstrated experimentally.

Proteins of the Eyespot Apparatus That Might Be Involved in Circadian Regulation

Both tactic movements (phototaxis and chemotaxis) in C. reinhardtii are controlled by the circadian clock (Bruce, 1970; Mergenhagen, 1984; Byrne et al., 1992). Therefore, it seems likely that the photoreceptor(s) relevant for circadian control and clock-related signaling components are located in or close to the eyespot. When searching the eyespot proteome for proteins that might be involved in the circadian input/signaling pathways, two candidates came up. One of them is the already mentioned blue light photoreceptor phototropin. The presence of blue light receptors in or close to the eyespot apparatus was not considered until now. Additionally, phototropin has not been characterized with regard to a possible circadian function. However, it is a potential candidate for a circadian photoreceptor in C. reinhardtii since physiological studies have shown that blue light (besides red light) can reset the phase of circadian phototaxis (Johnson et al., 1991; Kondo et al., 1991). Of course, this has to be experimentally analyzed in the future. Notably, phototropin is additionally located in the flagella (Huang et al., 2004; Pazour et al., 2005) as pointed out earlier.

The other protein found in the eyespot proteome that could represent a circadian-related signaling component is the above-mentioned CK1. Similar to phototropin, it is additionally located in the flagella (Yang and Sale, 2000; Pazour et al., 2005). Casein kinases belong to the Ser-Thr kinases. In Drosophila and mammals, CK1 is involved in the phosphorylation of PERIOD, a key oscillatory component thus gating the circadian feedback loop (Panda et al., 2002; Reppert and Weaver, 2002). In Drosophila, mutations of CK1 (known as DBT) either shorten or lengthen the period of circadian rhythms (Preuss et al., 2004). CK1 is highly conserved in C. reinhardtii as well as other circadian relevant Ser-Thr kinases (CK2 and SHAGGY) and phosphatases (PP1 and PP2A; Mittag et al., 2005). In the eyespot proteome, these other kinases and phosphatases were not found. However, two Ser-Thr phosphatases of type PP2C were present in this proteome, while PP1 and PP2A appear in the flagella proteome (Pazour et al., 2005).

CK1 Influences Several Processes, Including Hatching, Flagella Formation, and Circadian Phototaxis

CK1 represents a bona fide candidate as member of a circadian signaling cascade transducing light information that is taken up by one of the photoreceptors in the eyespot to the flagella, thus mediating circadian phototaxis and chemotaxis. Therefore, we decided to select at first CK1 among the eyespot proteins for further functional analysis.

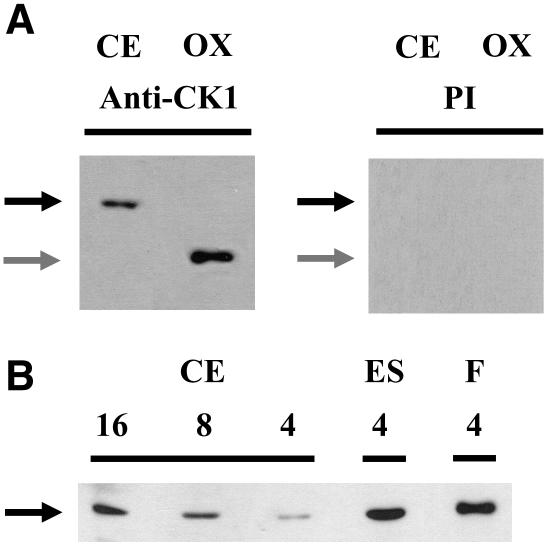

Presence of CK1 in the Eyespot and the Flagella

In the eyespot proteome, CK1 was only identified via two peptides. To verify enrichment of this kinase in the eyespot, we conducted protein gel blot analyses with antipeptide CK1 antibodies. Selectivity of the antibodies toward CK1 (theoretical molecular mass of 38.4 kD) was analyzed by comparison with preimmmune serum and by loading a low amount (1.5 ng) of overexpressed His-tagged CK1 lacking the N terminus (theoretical molecular mass 25.9 kD). While the anti-CK1 peptide antibodies detected a protein of ∼37 kD and the purified His-tagged CK1 fragment (determined molecular mass of ∼26.5 kD), these proteins were not recognized by the preimmune serum (Figure 6A). We also examined the presence of CK1 in a crude extract, an eyespot, and a flagella fraction. CK1 was clearly identified in the eyespot and the flagella fractions as well as in the crude extract (Figure 6B). Furthermore, CK1 is significantly enriched in the eyespot fraction and in the flagella in comparison with a crude extract. Presence of CK1 in the eyespot was verified in five independent preparations.

Figure 6.

CK1 Is Enriched in Eyespot and Flagella Fractions.

(A) Proteins from a crude extract (CE; 8 μg per lane) and overexpressed His-tagged CK1 lacking the N terminus (OX; 1.5 ng per lane) were separated on SDS-PAGE along with a molecular mass standard, blotted, and probed with antipeptide CK1 antibodies (anti-CK1) and preimmune serum (PI), respectively. The position of CK1 is indicated with a black arrow. Its determined molecular mass (∼37 kD) differs only slightly from its theoretical molecular mass (38.4 kD). In the case of the E. coli–overexpressed CK1, its determined molecular mass (∼26.5 kD; gray arrows) also differs only minimally from its theoretical molecular mass (25.9 kD).

(B) Proteins from a crude extract (CE; 4, 8, and 16 μg per lane), an eyespot (ES; 4 μg per lane), and a flagella fraction (F; 4 μg per lane) were separated on SDS-PAGE along with a molecular mass standard and immunoblotted with antipeptide CK1 antibodies. The position of CK1 is indicated with a black arrow.

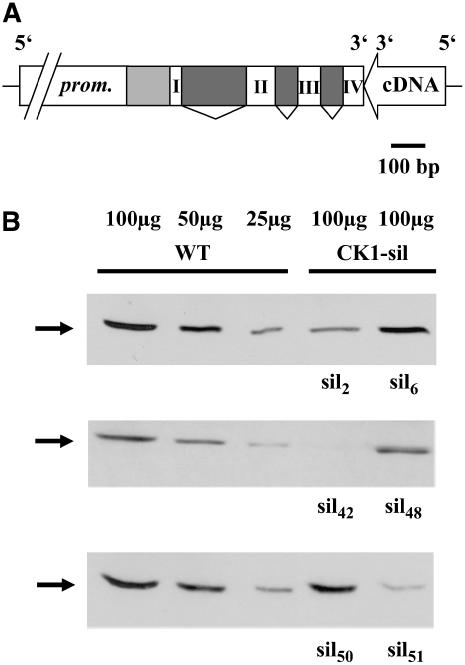

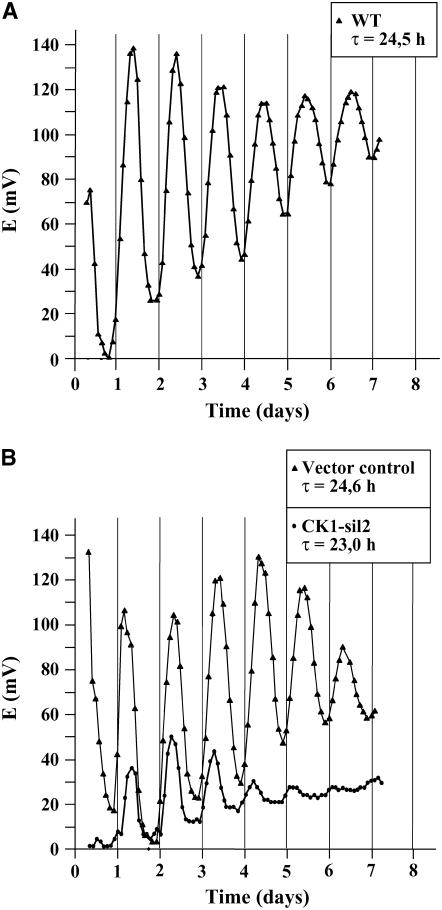

Silencing of CK1 Causes Period Shortening of the Circadian Phototaxis Rhythm and a Tendency to Arrhythmicity after 4 to 5 d

To obtain functional information about the role of CK1 in C. reinhardtii, it was silenced by RNA interference (RNAi). For silencing of CK1, an RNAi construct was created following the strategy developed for C. reinhardtii by Fuhrmann et al. (2001). Thereby, the potential endogenous promoter region of ck1 (780 bp upstream of the gene) along with the 5′ region containing its 5′ untranslated region and the first four exons, including three introns, were fused to a cDNA fragment covering exons 1 to 4 in opposite direction (3′ → 5′; Figure 7A). As selection marker, the aphVIII gene encoding resistance to paromomycin (Sizova et al., 2001) was used. Transformed strains growing on paromomycin were used for further analysis. Cells were grown up to a cell density of ∼4 to 5 × 106 cells/mL, and crude extracts were prepared. For comparison, a crude extract from nontransformed wild-type cells was used. CK1 silencing was checked in protein gel blot analysis with the antipeptide CK1 antibodies (Figure 7B). Different amounts of proteins from the wild type (100, 50, and 25 μg per lane) were separated on SDS-PAGE and quantitatively compared with proteins from transformed strains (100 μg per lane) after immunoblotting with the CK1 antibody. Equal loading was checked by Ponceau staining. While some strains showed only very little silencing of CK1 (CK1-sil6, CK1-sil48, and CK1-sil50), others were significantly silenced down. Thus, CK1-sil2 was silenced to a level between 25 and 40%; CK1-sil42 and CK1-sil51 were silenced even below 25% in comparison with the wild-type level of CK1.

Figure 7.

Silencing of CK1 by RNAi Down to Levels Below 25% in Comparison with the Wild Type.

(A) The RNAi construct used for silencing of CK1 is demonstrated. The numbers represent the involved exons. Dark gray regions are introns. The light gray area represents the 5′ untranslated region. The potential promoter region (prom.) comprises 780 bp in front of the ck1 gene.

(B) Different amounts of proteins from a crude extract (100, 50, and 25 μg per lanes) of wild-type cells were separated on SDS-PAGE (large-scale size) and used for protein gel blot analysis with the antipeptide CK1 antibodies along with proteins of crude extracts (100 μg per lane) from different CK1-silenced strains (CK1-sil).

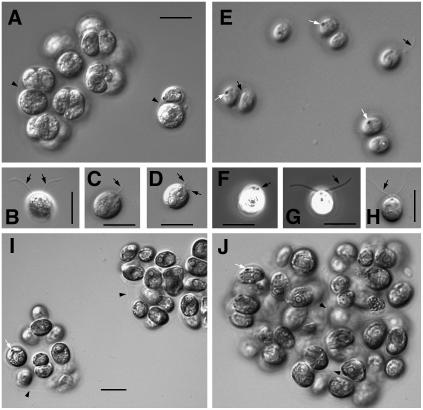

The three well-silenced strains (CK1-sil2, CK1-sil42, and CK1-sil51) were maintained and further analyzed by differential interference contrast and phase contrast microscopy. These analyses revealed that CK1 silencing causes multiple defects that depend on the degree of silencing. In all three stains, hatching (Figure 8, Table 2) and flagella formation (Figure 8, Table 3) were disturbed. The defects were more pronounced in Tris-acetate-phosphate (TAP) medium (used for usual culturing) than in minimal medium (used for phototactic measurements). In the CK1-sil2 strain (silencing between 25 and 40%), 19.2% of cells (TAP medium) and 54.3% of cells (minimal medium) occurred as single cells, while the others occurred as pallmeloids (aggregates of two or more cells within the mother cell wall). This phenotype is indicative for defects in hatching. In addition, flagella formation was affected. Only 31.7% (TAP) and 80.2% (minimal medium) of the cells had normal flagella. Others had either medium sized flagella, flagella stumps, or a bald phenotype. In the CK1 RNAi strains sil42 and sil51 that are silenced below 25%, the disturbances in hatching and flagella formation were even more severe. Thus, <10% (minimal medium) occurred as single cells (Table 2), and <8% from the single cells had normally size flagella (Table 3). Other obvious effects of CK1 silencing on the phenotype (e.g., pyrenoid or eyespot number) were not evident.

Figure 8.

Characterization of CK1-Silenced C. reinhardtii Strains by Light Microscopy.

(A) to (H) Differential interference contrast and phase contrast images of CK1-sil2 strain grown in TAP ([A] to [D]) or minimal medium ([E] to [H]). Cells tend to form aggregates (palmelloids) enclosed by the mother cell wall most likely due to defects in hatching ([A] and [E]). This tendency increases with the level of CK1 silencing. For quantitative analysis, see Table 2. Single cells also exhibit variation in flagella length. Cells with normal ([B], [G], and [H]; for quantitative analysis, see Table 3), intermediate (C), and flagella stumps ([D] and [F]).

(I) CK1-sil42 strain grown in TAP medium.

(J) CK1-sil51 strain grown in TAP medium.

Black arrows, flagella/flagella stumps; white arrows, eyespot; arrowheads, mother cell walls. Bars = 10 μm.

Table 2.

Silencing of CK1 Affects Hatching

| Percentage of

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Medium | Strain | Single Cells | Aggregates of Two Cellsa | Aggregates of More Than Two Cells |

| Minimal mediumb | CK1-sil2 | 54.3 | 34.2 | 11.5 |

| CK1-sil42 | 9.0 | 21.0 | 70.0 | |

| CK1-sil51 | 2.7 | 9.3 | 88.0 | |

| TAP | CK1-sil2 | 19.2 | 15.8 | 65.0 |

| CK1-sil42 | 12.8 | 20.2 | 67.0 | |

| CK1-sil51 | 2.6 | 9.0 | 88.4 | |

n = 292 to 500 analyzed cells/cell aggregates.

Analyses were done 24 h after transfer of cells from TAP to minimal medium.

Table 3.

Silencing of CK1 Affects Flagella Formation

| Growth Medium | Strain | Percentage of Single Cells with Normal Flagella |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal medium | CK1-sil2 | 80.2 |

| CK1-sil42 | 37.0 | |

| CK1-sil51 | 16.7 | |

| TAPa | CK1-sil2 | 31.7 |

| CK1-sil42 | 7.5 | |

| CK1-sil51 | 0.6 |

Cultures were treated with autolysin for 15 to 20 min to release cells from palmelloids before fixation.

These data indicate multiple functions of CK1 within the cell. In the case of hatching defects, for example, the autolysin production of vegetative cells that is necessary to release the daughter cells after division from the mother cell wall (Harris, 1989) might be disturbed. CK1 activity might therefore either be necessary in the autolysin production pathway or be involved in its release. Also, CK1 is clearly necessary for flagella formation. It was previously reported that CK1 phosphorylates a component of the abundant inner arm flagellar dyneins (Yang and Sale, 2000), and it may well be that additional flagellar proteins are also be phosphorylated by this kinase. In this context, it was also of interest to see if the remaining flagella of single cells of CK1-sil2 (∼30% of all cells) have wild type–like CK1 levels or also a reduced CK1 content. The latter would imply that silencing of CK1 down to a minimum degree finally leads to defect flagella formation. Flagella isolation from CK1-sil42 and CK1-sil51 was not considered as practicable due to the very low percentage of cells that have flagella. Thus, flagella from CK1-sil2 were isolated, and the level of CK1 silencing was checked by protein gel blot analysis. In addition, the eyespot from CK1-sil2 was also isolated to examine if the level of CK1 is in parallel reduced in the eyespot. A significant reduction in the level of CK1 was observed in both flagella and eyespot in the CK1-sil2 strain (Figure 9A). We also isolated the eyespot from CK1-sil51 where CK1 is silenced below 25% and checked in protein gel blot analysis if the CK1 level is reduced. Again, we found a significant reduction of CK1 (Figure 9B). Thus, silencing of CK1 occurs in both eyespot and flagella.

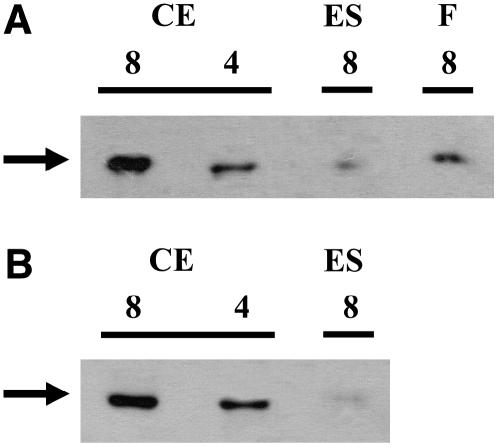

Figure 9.

The Level of CK1 Is Significantly Reduced in Flagella of CK1-sil2 and Eyespot Fractions of CK1-sil2 and CK1-sil51.

(A) Proteins from a crude extract of wild-type cells (CE; 4 and 8 μg per lane) and the eyespot (ES; 8 μg per lane) and flagella fractions (F; 8 μg per lane) of CK1-sil2 were separated on SDS-PAGE along with a molecular mass standard and immunoblotted with antipeptide CK1 antibodies.

(B) Proteins from a crude extract of wild-type cells (CE; 4 and 8 μg per lane) and the eyespot fraction (ES; 8 μg per lane) of CK1-sil51 were separated on SDS-PAGE along with a molecular mass standard and immunoblotted with antipeptide CK1 antibodies.

Black arrows indicate the position of CK1. Exposure time was lengthened in comparison with Figure 6B to allow detection of low amounts of CK1 in the subcellular fractions of the CK1-silenced strains.

We also aimed to check if phototactic behavior was disturbed by CK1 silencing. For this purpose, wild-type cells and CK1-sil2 cells were grown in a light/dark (LD) cycle and manually transferred to a phototaxis measuring unit during the middle of the day (LD 6 and 8) and during the middle of the night (LD 18 and 20). Wild-type cells showed a strong phototactic response toward the light source during the day but not during the night (Table 4). CK1-sil2 cells also showed an increased phototactic response toward the light source during the day, but the amplitude was significantly reduced in comparison with the wild type. This can be explained by the fact that only ∼30% of the CK1-sil2 cells represent single cells with normal size flagella and thus are fully motile. In conclusion, both strains exhibit a diurnal variation in their phototactic behavior with a maximum during the day.

Table 4.

Wild-Type and CK1-sil2 Cells Show Diurnal Phototactic Behavior

| Time | Strain | Extinction (mV) Reflecting the Amount of Cells That Swim to the Light |

|---|---|---|

| LD 6a | Wild type | 290.0 |

| LD 8a | Wild type | 265.0 |

| LD 18b | Wild type | 17.5 |

| LD 20b | Wild type | 22.5 |

| LD 6a | CK1-sil2 | 109.0 |

| LD 8a | CK1-sil2 | 96.0 |

| LD 18b | CK1-sil2 | 26.0 |

| LD 20b | CK1-sil2 | 24.5 |

LD 6 and LD 8: 6 or 8 h after light was switched on in a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle representing the middle of the day;

LD 18 and LD 20: 6 or 8 h after light was switched off in a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle representing the middle of the night.