Introduction

Medical and social care may be integratively associated within and outside of the health care sector. The societal idea of care of the elderly as part of a general welfare system may be seen as such integration. In this report, we will be discussing integrated care from both the general and the specific perspective. Experience from the Swedish “Ädel-reform” is our case1. The reform concerned care of the elderly and will be described in detail, and in this paper be referred to as “The Elderly Reform”.

Division, decentralisation and specialisation in health care introduce risks of fragmentation and loss of coherence regardless of whether the provider is public or private. Therefore, integrative mechanisms are necessary to create relations between the parts in all health care systems, independent of financing systems and responsibilities for production [6].

A complex system is one, where the parts or actors cannot fulfil the over-all aims without co-operation. Relations between people working in them at all levels create the systems and structures in all complex organisations. Interdependency between units and parts as well as the complementary role of each of them are important features (Scott 1961) [5, 29]. The need of frequent communication between different system units can be reduced by agreements on specific administrative activities and standardisation—guidelines. IT-systems are used to facilitate the integration (Channell 1998).

Integration is a structural and process issue. When integration is lacking patients are lost, activities do not take place, or are delayed (Berwick 1997). Disintegration arises from lack of information or communication as well as due to lack of ability to evaluate and interpret changes in the environment. Disintegration means lack of co-ordination, and is a management problem [27]. System negligence is at the root of medical error [21].

In 1992, the “Elderly Reform” in Sweden came into force. This reform is a good example of a change in paradigm to achieve decentralisation and integration of care and cure. It is a system of comprehensive, pooled or serial, instrumental activities directed toward persons above the age of 65.

“Chain-of-care” or integrated care in the “Elderly Reform-ideology” means successive steps for a patient from primary health care, through specialised care within or outside of a hospital and back to a nursing home or the ordinary home in co-operation with primary health care. Four levels of professional organisations are involved in this transition and two societal bodies. The weak parts of the chains are the steps from one caregiver to the next. If these transitions are smooth we may achieve “seamless care” [9, 14, 28], (Parse 1998).

The Swedish system

Universally, reforms of health care systems have shifted the power from central to periphery [25]. In Sweden the devolution started after WW II when primary health care and psychiatry were still provided by the government, also in charge of the University hospitals. Today all health care in Sweden is run by democratically elected regional county councils or local municipalities. The national government is responsible only for forensic medicine, health care in the prisons, in the national defence and for refugees and immigrants who have not yet been admitted to a municipality.

The counties and communities have a strong position resting on their right to levy local taxes. These taxes are without exemptions and with direct proportionality. Today about 30 percent of the personal income is paid as a local tax to the county and community. The counties receive one third mainly for health care. It is not a system where federal taxes are re-distributed as in the UK or Norway. The system is, together with the Finnish, one of the most decentralised. Approximately 70% of county council revenues are derived from direct taxes, 15% from the federal government and the rest from patient charges. The level of co-payment is 20% if drugs and dental care are included. The responsibility for the counties also includes planning and financing of most of the privately supplied care, which is mainly publicly financed.

The county councils have great freedom to decide the structure of health and medical care in their geographical regions. The balance between primary and secondary care is decided by the local county and on tertiary care in co-operation with other counties in the region. The legal basis is to supply all citizens with “good care”. The national government acts through advice and has legal power only in matter of security, such as epidemiology of contagious diseases, and in matters of competence and accreditation of systems and equipment, or licensing of personnel.

Primary health care districts form the basic level and have a geographical responsibility. These centres are organised with GPs, district nurses and midwives. GPs are employed by the counties or have a contract with the county. Contracts are generally based on capitation.

Formal referral—“gate-keeping”—from a GP or a family physician is not needed to visit a hospital clinic or to be admitted for hospital care. This freedom to seek care and for the hospitals to be reimbursed may stimulate hospitals to produce more medical care than may be “needed”, especially after the introduction of pre-payment systems. There is a risk for “crowding-out” of planned activities in favour of unplanned, non-emergencies entering through the A&E [4]. This phenomenon is illustrated by large local and regional variations in utilisation of hospital treatment for common diseases.

The local level in the Swedish system is care provided by the community based on local taxes. Before the Elderly Reform municipalities were responsible for the social sector with its specific legal basis. After the Elderly Reform, the local municipalities carry the organisational and financial preconditions to provide for all types of care for the elderly above the age of 65 and the responsibility for psychiatric care of the long term ill.

Policy formulation and problems to be solved by the Elderly Reform

In contrast to many other countries, care of the elderly in Sweden before 1992 was a responsibility for the health care sector i.e. the counties, and not for the social sector i.e. the local municipalities, and was supplied in county-owned local nursing homes in close co-operation with local hospitals and primary care. Communities were responsible for social care based on that legislation, while counties were guided by the health care legislation—rights for the client versus obligations for the provider. The drawback was unnecessarily high levels of medical care with over-use of technical facilities and medication, according to the biomedical rather than the social paradigm.

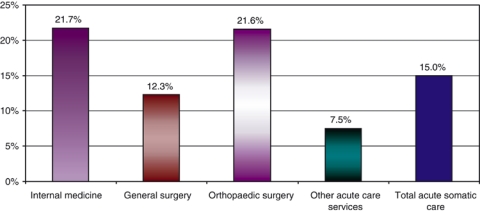

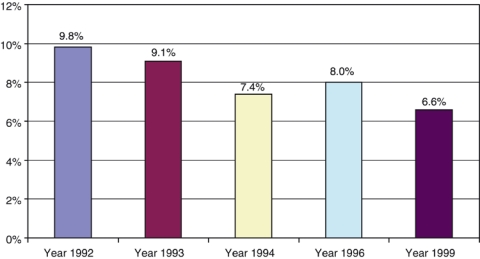

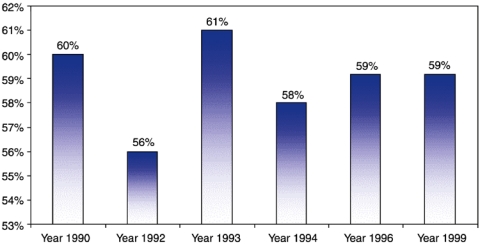

The immediate reason for the Elderly Reform was the problem with “bed-blockers” resulting in crowding out effects and long waiting lines to specialised care. In highly specialised units such as neurosurgery or orthopaedics patients waiting for rehabilitation, nursing care and palliative care in appropriate settings. At the same time, many patients had to wait months and years for hip replacement, heart surgery or other planned procedures. During this time the number of patients who occupied beds at hospital departments was growing. The Federation of County Councils reported that in 1989–1990 15% of all beds at acute somatic care departments were occupied by “bed-blockers” waiting for discharge (Figures 1 and 2). About 60% of all waiting patients were 80 years or older (Figure 3). 75% waited for further long time care in the counties.

Figure 1.

Fractions of in-patients waiting for discharge from acute care hospitals in Sweden year 1990.

Figure 2.

Fractions of patients (%) waiting for discharge from somatic care hospitals during 1992–1999.

Figure 3.

Patients 80 years and older waiting for discharge from acute care hospitals from 1990 through 1999. Geriatrics excluded. Fraction of all in-patients (%).

But a more basic reason was the urge in the society for a change of paradigm in support of elderly persons with age-related disabilities from a high technology, intensive and biomedical to a more individualised, empowered, quality-of-life directed perspective. The political trends were supporting freedom of choice and autonomy. From a quality perspective, it was not acceptable to care for elderly persons for weeks and months in departments for acute somatic care in overcrowded wards with low levels of autonomy, no privacy and low levels of competence for the type of palliative care needed [16].

The third important aspect was economy. Cost for care of a person in a specialised ward is higher than in a nursing home, even if the “bed-blockers” only use the “hotel-function”. It was anticipated that a more comprehensive responsibility for care of the elderly within the communities should trigger the development towards more cost-effective methods. The possibility to develop a more integrated care—the Danish example was important—within the local community was supposed to lower the cost. This aim was even more important, facing the rising numbers of elderly persons needing care in the near future.

To complete the picture of the early 1990s should be added the “waiting-time guarantee” similar to the NHS and Norway among others. In Sweden ten separate groups of patients were included, who should be offered treatment within three months from the day of the decision to treat. If the guarantee could not be kept, patients were free to see any other provider, even private (Socialstyrelsen 1997). The guarantee was supported by seed money from the government during 1992, and was kept in action in the counties for two years or longer. This service reform triggered better waiting line administration as well as a more efficient use of hospital beds, and was supported by the concomitant and politically co-ordinated Elderly Reform.

Solutions chosen

In January 1, 1992 the Elderly Reform came into force. The aim of the reform was “to provide municipalities with the organisational and financial preconditions to offer freedom of choice for the patient, security and integrity in the health care and social services for the elderly and disabled.” Another important aim was to promote a more efficient use of society's resources.

In short, the Elderly Reform states that:

The municipalities have the statutory responsibility for financing and quality in all types of institutional housing and care facilities for the elderly (including nursing homes);

The municipalities have the responsibility to provide health care to elderly residents within institutional housing and care facilities.

The municipalities were also given the right to take over the responsibility for home nursing care if they could reach an aggreement with the county councils. However, the responsibility to provide health care does not include care provided by physicians;

The municipalities are financially responsible for long-term institutional care also in facilities, which they themselves do not operate as principals. The responsibility includes patients regarded as “bed-blockers” in acute somatic hospital care and geriatric clinics;

The municipalities were also given the responsibility to provide handicap-aids;

Each municipality is obliged to establish a “special medical nurse”-function, with the prime task to monitor the quality of care according to laws and regulations, not to see individual clients.

To support this revised allocation of responsibilities, a total sum of 20 billion SEK was transferred from counties to municipalities. This corresponded to 20% of total cost for health care in 1992. The Elderly Reform also included 3 billion SEK as incentive grants from the Government to improve the quality of housing for the elderly and disabled in communities.

With the reform the municipalities received the full responsibility for nursing homes. Most of these nursing homes before the reform were owned and managed by the counties. The total number of beds in the counties in 1991 was 93,000 (12/1000 population). Through the reform one third of these (31,000) were transferred to the communities.

The change of paradigm from medical to social care was manifested in the development of new linguistic terms. Care given in all kinds of housing, nursing homes etc, run by the communities by definition is outpatient care. These dwellings are called special living in contrast to own living, meaning ordinary living conditions in an apartment or a house. However, even in special living persons are tenants and not patients. Accordingly persons living in these nursing homes pay separate rent, cost for food, nursing and medical care. It is not a package, the content of which is decided by the community, but offers a variety of choices.

The other important new term is medically completed treatment, meaning that the specialised care is completed and cannot offer any extra benefit, however, the person may need other kinds of care such as nursing home or home care. Three days after notification from a hospital to the community that a person has completed the medical treatment, the community becomes financially responsible for the person's care.

Political process and support for implementation

The main idea behind the reform was to “de-medicalise” care of elderly persons with “normal” disabilities and illnesses characteristic for the process of ageing by the introduction of a health care paradigm into the local communities. Employers in the care-sector in the communities were used to the legislation for social care, with formal decisions and legal rights for the clients. Now they had to combine these principles with the principles of health care based on obligations for the community as a provider, but without formal rights for the patients. The main difference is that needs assessment is made from different perspectives. Nurses and other health personnel had to accept leaders from the social tradition.

The political process was incremental, according to the Swedish tradition of consensus politics through negotiations with all parts and compromise solutions. Already in 1980 the first committee was appointed, which in 1987 published new principles for the care of the elderly: autonomy, integrity, security and free choice of care (Prop 1987/88:176). The next committee (“Äldre delegationen”; see Introduction) suggested the change of responsibility between public providers, which was established in the Elderly Reform. Before the implementation the government negotiated the financial agreements between the central offices for counties and communities. The transfer of taxes was based on these deliberations, which in turn were based on available facts at that time.

The reform was mainly based on the transfer of responsibilities reflected in changes of legislation, and taxation. The new national legislation and regulations constituted a framework for further implementation, and did not give any details except the rules for payment for patients regarded as bed-blockers. Details were expected to be developed by national administrative bodies and through agreements and contracts between parts at local level.

The whole process of implementation was systematically followed and evaluated by the National Board of Health and Welfare and guidelines were developed to support norms for appropriate organisational behaviour [1–3, 24]. These included the practical interpretation of the term “medically completed treatment” (1992), the regulations on responsibilities and competence of the special medical nurse function (1992), and the requirements of discharge planning and transfer of information between providers (1995).

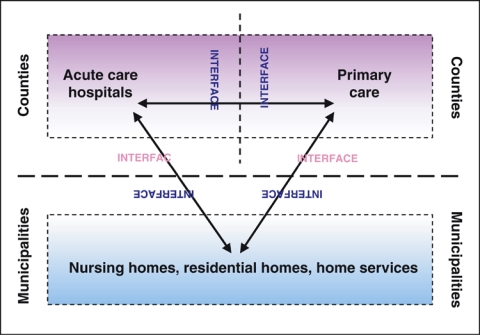

Figure 4 shows the principles for co-operation between counties and municipalities as providers of care according to the Elderly Reform. Note that family practitioners in primary health centres are employed by the counties and are responsible for medical care in nursing homes operated by the communities. The municipalities employ nursing staff.

Figure 4.

Relations between providers according to the Swedish Elderly Reform.

Success of implementation

The immediate results of the implementation of financial responsibilities was a reduction of the number of “bed blockers”, which has gone down from one out of five patients in acute hospital care to 6%, and stabilised at a low level (Figure 2). Particularly elderly patients have shorter length of stay (Figure 3). All beds have become active or have been closed and the average length of stay in acute hospitals has been reduced down to four days for surgery and five days for internal medicine. The most common length of stay is currently two days.

The waiting time for discharge has been shortened down to three days—the notification time. For the counties this reform—in addition to other ongoing changes—has led to a reduction of the number of beds from 12/1000 in 1988 to 4/1000 in 1998. In acute hospitals the number of beds fell from 6/1000 in 1988 to 3.5/1000 in 1998. In geriatric care this reduction was greatest (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fractions of in-patients waiting for discharge from hospital departments in Sweden 1990–94.

| Hospital departments | 1990 % | 1992 (Elderly-reform) % | 1993 % | 1994 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 21.7 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 7.9 |

| General surgery | 12.3 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 4.6 |

| Orthopaedic surgery | 21.6 | 8.6 | 12.1 | 11.0 |

| Other acute care services | 7.5 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| Total acute somatic care | 15.0 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 6.1 |

Effects of the reform

It is now possible to identify the major structural effects of the reform. First, the former problem with “bed-blockers” in hospital care has diminished. Second, the number of special housing alternatives for the elderly have increased considerably. Third, the municipalities have increased the number of qualified nursing care personnel. Finally, the “special medical nurse”-function has meant an increased awareness and higher general standard of quality of nursing care in the municipalities.

Consequently the pressure on all parts of the integrated care of the elderly increased in terms of resources and competence. The shortened length of stay in acute hospital care also increased care-load in the nursing homes. At any given time, there are usually patients in every nursing home requiring advanced medical care (e.g. terminal care patients). Even if the quality of care has developed considerably, it is still possible to find an extensive use of tranquillisers and sedative medication, patients with pressure soars and (urine-) catheters.

The main political aims were reduced societal costs, higher effectiveness and efficiency in acute somatic care and freedom of choice for the elderly to receive care in home-like settings with less medical treatment. In all three respects the reform has been a success. However, as a consequence of the changes in demography over the decade after the reform was invented, there has been an additional increase of care-load in municipal elderly care and the ambitions to develop a more socially oriented (“de-medicalised”) elderly care have only been partly fulfilled. In addition, many elderly patients in community care do not receive the medical treatment needed. Finally, due to the increasing number of very dependent persons communities have had to stratify nursing homes according to needs. This has led to a minimum of choices for the elderly, and in this respect the recent development demands a new reform. This should not be misinterpreted as a failure of the Elderly Reform.

The well-defined need of provision of low technology care in the communities opened a new field for alternative providers, i.e. private and corporate. Consequently there has been a rapid increase of private providers in many communities regardless of political majority.

Remaining problems and future development

Due to the continued changes with more and more persons with large needs in community care, practitioners and physicians should be more involved, without jeopardising the aim of de-medicalisation.

The construction of the reform included a mix between mandatory and non-mandatory elements, e.g. the responsibility for home nursing care. According to several studies, continuity and collaboration seems to function less well, when responsibility for home nursing care is divided between two separate authorities. Similar problems have been brought forward regarding the provision of handicap-aids, although the main problem here is targeting of services.

In a long-term perspective the evaluations have pointed out a need to improve and develop basic and continuing staff training programs, in particular in counties, which did not introduce as many educational programs regarding the care of the elderly as municipalities did. Finally, there is continued need to make service provisions more consumer-oriented in terms of freedom of choice, security and integrity.

Discussion and conclusions

From the late 1980s, Swedish politics was influenced by new ideas on what constitutes effectiveness and efficiency in organisations. The ideal of the private company as the most effective and efficient was introduced, as well as new expectations on quality of services. The citizens should be regarded as customers and the traditional Swedish model of stabile administration as supporting justice and equal access was replaced by the model of more organic organisation, able to adopt to changing environments, and efficient as private companies in an open market. Requirements on decentralisation and reduced central governance led to the following transformation of the Swedish legislation from traditionally detailed laws and instructions to more general recommendations and only sporadic regulations. This development was also reflected in the Elderly Reform that only stated a few central, national principles, and left the details to the local level.

In the light of the political and economic transitions in Europe at the end of the 1980s a more individualistic approach had been legitimate and replaced the collective and group oriented approach from the 1960s and 70s. The sensitivity to individual needs of the elderly as a political goal replaced the macro level oriented and mechanistic approach applied previously to all issues regarding public policy.

There are both democratic and quality consequences of the reform. The laws, which only constituted the framework for this large-scale institutional change, left open for alternative provisions and various standards of quality of care due to economy in counties and communities, as well as the global conjuncture. The medical consequences of the reform often were undesirable variations in the access to medical and nursing services, as a response to the local allocation of resources and different ideologies on how to prioritise, manage and integrate organisations. On the other hand, the reform created possibilities for various organisational experiments, consistent with the values prevalent in different local communities.

The reform also increased the awareness and created potential to adopt to ongoing changes in medical technology and the growing number of elderly, and created preconditions for further development, such as “hospital at home” or other alternatives to institutional care. In this respect the reform may be regarded as an invisible and generally unrecognised instrument for prioritisation.

The main steering mechanism of the reform was not only the introduction of financial incentives but also the division of the process of illness into an acute, short-term period and conditions lasting for longer periods and subsequently requiring long-term care. This division was reflected in the physical division of resources and the development of geriatrics as a speciality taking care of emergency conditions of the aged, belonging to the field of internal medicine. In acute care hospitals there was an increased demand for specialised nurses and in communities a new need for generalist nurses and nurse assistants with medical training.

The Swedish Elderly Reform in essence was a decentralisation and the concept of integrated delivery systems is central to the idea of decentralisation. The regional model was the underlying concept in the NHS and in other systems internationally [14]. In the USA this concept was known already in the 1960s- and 1970s, and re-emerged when the American Hospital Association proposed “community care networks” in the 1990s, that now are referred to as integrated delivery systems [15].

According to Luke and Wholey, integrated delivery systems help to eliminate redundancies in service capacity, generate synergies in the provision of care, and improve the flows of patients through the increasingly webbing of health care delivery.

The aim of the Swedish Elderly Reform to decentralise, specialise and integrate included all three aspects. Redundancy was apparent before the reform with caring in acute hospitals for persons more appropriately taken care of in nursing homes. Before the reform the basic security for the elderly was interrupted when people became sicker and the responsibility moved from the community to the county. By transferring responsibility and by integrating social and medical activities in the community the main flow of elderly patients was no longer a problem.

Organisational control and co-ordination are key features for maintaining organisational rationality. Differentiation means almost the same as specialisation, but also reflects the interaction between organisations and their environment [27]. Through the Elderly Reform acute hospital care as well as community care specialised in separate sectors. Before the reform many bed-blockers received lousy care by personnel trained for acute and emergency tasks. When these patients were moved to the communities, co-operation with families and exposure to the environment became natural.

Flaws in communication between providers threatened the Elderly Reform; accordingly a specific governmental regulation was issued on transfer of relevant information from hospitals to community care. In one study, we found that the format of information from one provider to the next was not well adjusted to the needs of the caregiver or to the patient's needs. Most alarming was the lack of correct information regarding medication (Andersson 1997).

Integrative activities comprise both structure and processes between parts of a system. They reflect both relationships across the system as well as incentives of participants. The actions undertaken of an organisation in order to reduce uncertainty in the environment or in relationships between their parts describe co-operation strategies, and the integrative efforts of an organisation [29]. To support the reform many counties and communities developed common guidelines for large groups of patients such as for stroke, heart failure and COPD.

Integration can be accomplished either through ownership or contractual relationships. These forms of integration have been referred to as vertical and virtual, respectively. Ownership-based integration can reduce transaction costs and can lower production costs associated with achieving economies of scope and scale. Contractual-based integration provides increased flexibility in response to changing conditions in the environment and offers opportunities for learning and building trust. Integrative structures can be built into contractual relationships and strengthen the linkages across contracting organisations. These provisions involve additional costs not present when the service is directly provided by an organisation [6].

According to Shorthell and co-workers (1994) efforts to more tightly link hospitals and physicians can be classified as clinical, physician, and functional integration.

Clinical integration is defined as the extent to which care is co-ordinated across various personnel, functions, activities, and operating units of the organisation.

Physician integration is the extent to which physician may identify with the system and participate in its planning, management and governance.

Functional integration address the extent to which key support functions and activities such as financial management, human resources, strategic planning, information management, and quality improvement can be co-ordinated across operating units.

The Swedish Elderly Reform presupposed contractual-based integration between providers with separate financing and contracts for exchange of tasks and money. Population-based statistics with personal identification numbers have kept cost for bookkeeping low. However, transaction costs have been substantial due to the lack of clear-cut rules and need for negotiations on individual cases as well as the slow development of common clinical guidelines.

Through the Elderly Reform the traditional link between practitioners and nursing homes was cut. Before the reform, when counties operated nursing homes, there were regular walk-rounds as in hospitals. This traditional sign of a medical environment was looked at by disgust by many and represented a medicalisation of social care. This habit disappeared, however, also the advantages by a close contact between practitioners and nursing homes. Clinical and physician integration was lost.

According to Scott (1961), interaction between parts of every human system of organised behaviour occurs by three kinds of linking processes: communication, balance and decision-making . Communication may be formal or informal, vertical-horizontal, line-staff, and functions as a mechanism which links the segments of the system together. It acts as stimuli resulting in action but also as a control and co-ordination mechanism, that links the decision centres in the system into a synchronical pattern. Thompson [29] argued that integrative mechanisms vary due to the nature of dependence between system levels or parts. By standardising communication and information exchange the need of frequent communication could be reduced, when there are serial dependencies between system units.

Although the Elderly Reform was supported by special legislation on communication between providers, there still after eight years, are important flaws. However, this is an area in which many providers work together to formalise and simplify flow of information. Many such projects aim at using IT more efficiently (Channell 1998).

Lessons learned

The Elderly Reform in Sweden was a political experiment with great success. Even if the Swedish Federation of Physicians did not support the change due to “disruption of primary care continuum for some patient groups” translated to “we will lose power” [18], today there are few arguments for returning to the former division of responsibilities between providers. The de-medicalisation of care for the elderly has been widely accepted. In addition, the role for community nurses became more prominent, one of the political goals, when primary care practitioners did not support care of the elderly in the local communities, which had limited experience of medical care. This support failed when nursing homes and home care were transferred from the counties, the employers of primary care physicians, to the municipalities, employers for the nurses.

The Elderly Reform relied on self-regulating systems, individual case co-ordination, professional adaptation, and communication between professionals. The effects of the lack of details in the legislation were conflicts between professionals in clinical care, nursing care and social care, all with competing goals and different definitions of quality. This conflict was related to the shift of power, and to preservation of microcultural professional identity instead of assimilation of increased diversity through differentiation [11].

New, subordinate goals were not developed supporting interorganisational efforts. According to Provan (1992) case co-ordination needs more than referrals i.e. reciprocal activities and mutual professional commitment. There was a lack of cross-professional process- and outcome measures describing outputs and outcomes of the large-scale process innovation. In addition, a commonly accepted clinical definition of “medically completed treatment” was not established, which introduced uncertainty about the need of resources and skills in municipalities and in primary health care. This lack of demarcation induced duplications as well as time consuming conflicts on organisational level.

The result of the decentralisation was a dilution of responsibilities due to the lack of definitions of tasks and their limits, and with professional norms and cultures—without incentives—as the backbone. The change from the planned, hierarchical and stable form of organisation to a more dynamic, organic form, characterised by strong reliance on cross-professional co-operation and one-by-one management instead of population based aims, led to “The Old Maid game”: this is not my responsibility.

Health care in Sweden certainly has many problems, such as waiting lines and unnecessary low levels of patient-centred service, however, these are due mainly to demography and lack of leadership, and not to the various reforms that have been implemented during the last decade. On the contrary, in the future there will be a continuing de-medicalisation and further development of the subsidiary principle, a heavier load for the family and an increased statutory responsible for communities, possibly supported by primary health care.

Footnotes

The ÄDEL reform

The concept of “Ädel” is an abbreviation of “Äldre (meaning elderly in English) Delegation” a governmental committee designing the reform. In addition the word “ädel” has its own meaning: pure, precious or nobel. Therefore, the “Ädel”-concept is a non-translatable word-game with positive associations.

Contributor Information

Grazyna Andersson, University of Uppsala, Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Health Services Research, Uppsala, Sweden.

Ingvar Karlberg, Professor of Health Services Research, Nordic School of Public Health, Göteborg, Sweden.

References

- 1.Andersson G. Admissions and discharges of patients 65 years and older from 19 ED:s at departments of internal medicine in Sweden in April 1994. On behalf of the Swedish government. Reference number 95-00-55. The National Board of Health and Welfare; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson G, Wester PO, Karlberg I. Admissions and readmissions to departments of internal medicine in Alvsborg and Skaraborg. Reference number 1995-81-8. Countywide surveillance, The National Board of Health and Welfare; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson G. How are the needs of patients satisfied after discharge from hospital? Reference number 95-82-5. Countywide surveillance, The National Board of Health and Welfare; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson G, Karlberg I. Lack of integration, and seasonal variations in demand explained performance problems and waiting times for patients at emergency departments. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00113-5. Submitted February 18, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batalden PB, Mohr J. Building Knowledge of Health Care as a System. Quality Management in Health Care. 1997;5(3):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazzoli G, Shortell SM, Dubbs N, Chan C, Kralovec P, Methods A Taxonomy of health networks and systems: bringing order out of chaos. HSR, Health Services Research. 1999;33(6):1683–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellandi D. Integrating systems for chronic care. Modern Health Care. 1999;29:32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick D. Controlling variation in health care. A consultation from Walter Shewhart. Medical Care. 1991;12:29–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burda D. Seamless delivery. Modern Healthcare. 1992;22:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Channell T. Getting it straight. Health Service Journal. 1988;108:32–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox TH. Intergroup conflict. In Cultural diversities in organisations. San Francisco CA: Berret-Koehler Publ; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Federation of County Councils and The National Board of Health and Welfare. Hospital In-Patient Care. Annual statistics on hospital activity. Stockholm, Sweden: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gramann D. New frontiers in integrated care. Caring. 1999;18:14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibberd PA. The primary/secondary interface. Cross-boundary teamwork—missing link for seamless care? Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1998;7:274–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1998.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luke RD, Wholey DR. Commentary: On “Taxonomy of Health Care Networks and Systems: Bringing Order Out of Chaos”. HSR, Health Services Research. 1999;33(6):1719–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maxwell RJ. Quality assessment in health. British Medical Journal (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288(6428):1470–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrisey MA, Alexander J, Burns LR, Johnson V. The effects of managed care on physician and clinical integration in hospital. Medical Care. 1999 Apr;37(4):350–61. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munkhammar L. I Ädel-reformens skugga. Editorial. Läkartidningen. 2000;22(97):2705. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mur-Veeman I, Raak van A, Paulus A. Integrated care: the impact of governmental behaviour on collaborative networks. Health Policy. 1999;49:149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onafowokan A, Mulley GP, editors. Age-related geriatric medicine or integrated medical care? Age Ageing. 1999;28:245–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Øvretveit J. System negligence is at the root of medical error. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 2000;13:103–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips-Harris C. The acute and long-term care interface. Integrating the continuum. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 1995;11:481–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pyle TO, Connell S. Seamless. Frontiers of Health Services Management. 1993;9:42–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rinder L, editor. Overcrowding—about the elderly at hospitals. Evaluation report 1994:12. Stockholm, Sweden: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saltman RB, Figueras J, editors. European health care reform. Analysis of current strategies. WHO Regional publications, European series, No 72, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott WG. Organization Theory: an overview and an appraisal. In: Shafritz JM, Ott JS, editors. Classics of Organization Theory. 4. Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996. pp. 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafritz JM, Ott JS. Classics of Organization Theory. 4. Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Southworth A. A seamless service for community care. Nursing Standard. 1992;6:40. doi: 10.7748/ns.6.27.40.s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson JD. Organisations in action. McGraw-Hill; 1967. [Google Scholar]