Abstract

The present study investigates further the population structure of Candida dubliniensis and its ability to exhibit microevolution. Using 98 isolates (including 80 oral isolates) from 94 patients in 15 countries, we confirmed the existence of two distinct populations within the species C. dubliniensis, designated Cd25 group I and Cd25 group II, respectively, on the basis of DNA fingerprints generated with the C. dubliniensis-specific probe Cd25. The majority of Cd25 group I isolates (48 of 71, 67.6%) were from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals, whereas the majority of Cd25 group II isolates (19 of 27, 70.4%) were from HIV-negative individuals (P ≤ 0.001). Nucleotide sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of the rRNA genes from 19 representative isolates revealed the presence of four separate genotypes. All of the Cd25 group I isolates tested belonged to genotype 1, while the Cd25 group II population was comprised of three distinct genotypes (genotypes 2 to 4), which corresponded to distinct clades within the Cd25 group II population. These findings were confirmed using genotype-specific PCR primers with 70 isolates. We also showed that C. dubliniensis can exhibit microevolution in vivo and in vitro as occurs in other yeast species. DNA fingerprinting using the C. dubliniensis probes Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 and karyotype analysis of multiple oral isolates recovered from the same specimen from each of eight separate patients revealed microevolution in six of eight of the clonal populations. Similarly, sequential clonal isolates from various anatomical sites in two separate patients exhibited microevolution. Microevolution was also shown to occur when two clinical isolates susceptible to fluconazole were exposed to the drug in vitro. The epidemiological significance of the four C. dubliniensis genotypes and the ability of C. dubliniensis to undergo microevolution has yet to be established.

Candida dubliniensis was first identified as a novel Candida species in 1995. It is closely related to Candida albicans, with which it shares many phenotypic characteristics, including the ability to produce germ tubes and chlamydospores and resistance to cycloheximide (57). As a result of these similarities, in the past many isolates of C. dubliniensis have been misidentified as C. albicans, hampering comprehensive epidemiological analysis of this species (56). In recent years a number of tests have been developed which have permitted the rapid and reliable identification of C. dubliniensis in clinical samples.

Phenotype-based tests such as the analysis of carbohydrate assimilation profiles using commercial yeast identification systems (38), growth temperature (39), differentially colored primary colonies on CHROMagar Candida medium (8, 34), chlamydospore production and colony morphology on birdseed agar (1, 53), and molecular tests based on PCR technology (10, 11, 20, 35, 58) have all been shown to be useful in the identification of C. dubliniensis. Using these techniques, C. dubliniensis isolates have been identified throughout the world in a wide variety of patient cohorts (1, 16, 17, 19, 28, 29, 40, 42, 54). Originally associated with oral carriage and oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and AIDS patients (3, 29, 30, 57), C. dubliniensis has more recently been identified in cases of systemic disease in Europe, the United States, and Australia (4, 28, 31, 46).

In an attempt to improve our understanding of the epidemiology of C. dubliniensis, in 1999 Joly et al. (17) developed and characterized three complex DNA fingerprinting probes for C. dubliniensis, one of which (Cd25) was species specific. The remaining two probes (Cd1 and Cd24) reacted weakly with C. albicans DNA. As well as providing a useful means of investigating the epidemiology of C. dubliniensis, the existence of the species-specific sequences contained within Cd25 provided further evidence that C. dubliniensis is a distinct species.

The Cd1 and Cd24 probes were shown to be useful for detecting in vitro and in vivo microevolutionary events, whereas Cd25 yielded stable complex fingerprint patterns suitable for the comparison of strains in epidemiological studies. This probe was used to fingerprint 57 independent C. dubliniensis isolates from 11 countries (17). Computer-assisted analysis of the fingerprints obtained using the software package DENDRON (17, 52) demonstrated that the C. dubliniensis isolates could be clearly divided into two separate groups, groups I and II. Group I isolates comprised 86% of those tested and were all closely related (average similarity coefficient [SAB] = 0.80), whereas the group II isolates, which comprised the remaining 14%, constituted a less closely related clade (average SAB = 0.47).

The purpose of the present study was to investigate further the genetic diversity of C. dubliniensis by analysis of Cd25-generated fingerprint profiles using a larger number of isolates from around the world taken from a broader range of anatomic sites. Secondly, this study sought to determine if the two groups identified on the basis of Cd25-generated fingerprint profile analysis represent specific genotypes which can be differentiated based on nucleotide sequence analysis of the internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS) of the rRNA gene cluster. The third objective of this study was to further investigate the phenomenon of microevolution in C. dubliniensis, both in vivo and in vitro, using the three fingerprinting probes described by Joly et al. (17).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. dubliniensis clinical isolates and culture conditions.

Ninety-eight isolates of C. dubliniensis from 94 separate individuals in 15 different countries were included in this study (Table 1). In addition, multiple single-colony isolates of C. dubliniensis recovered from the same clinical specimen obtained from eight separate individuals (patients A through H, Table 1) were also studied.

TABLE 1.

C. dubliniensis isolates used in this studya

| C. dubliniensis isolate | AIDS or HIV status | Sample | Yr of isolation | Country of origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD71 | + | Oral | 1994 | Argentina | 54 |

| CM1 | + | Oral | 1991 | Australia | 57 |

| CM2 | + | Oral | 1991 | Australia | 57 |

| CM4 | + | Oral | 1991 | Australia | 57 |

| CM5 | + | Oral | 1991 | Australia | 57 |

| CM6 | + | Oral | 1992 | Australia | 57 |

| Can 6 | + | Oral | 1995 | Canada | 39 |

| Can 1 | + | Oral | 1996 | Canada | 39 |

| Can 3 | + | Oral | 1996 | Canada | 39 |

| Can 4 | + | Oral | 1996 | Canada | 39 |

| Can 9 | + | Oral | 1996 | Canada | 39 |

| Can 13 | + | Oral | 1996 | Canada | 39 |

| CD516 | + | Oral | 1996 | Finland | 39 |

| CD96.29 | + | Oral | 1996 | Germany | 39 |

| CD96.34 | + | Oral | 1996 | Germany | 39 |

| CD96.54 | + | Oral | 1996 | Germany | 39 |

| CD96.63 | + | Oral | 1996 | Germany | 39 |

| CD159 | + | Oral | 1995 | Greece | 39 |

| CBS2747 | − | Sputum | 1952 | Netherlands | 31 |

| CBS8500 | − | Blood | 1998 | Netherlands | 31 |

| CBS8501 | − | Blood | 1998 | Netherlands | 31 |

| CD98923 | + | Oral | 1998 | India | 1 |

| CD36 | + | Oral | 1988 | Ireland | 57 |

| CD500 | AIDS | Oral | 1988 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD33 | + | Oral | 1989 | Ireland | 57 |

| CD38 | + | Oral | 1989 | Ireland | 57 |

| CD503 | + | Oral | 1989 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD505 | + | Oral | 1989 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD506 | AIDS | Oral | 1989 | Ireland | This study |

| CD57 | − | Vagina | 1992 | Ireland | 32 |

| CD507 (A, 18) | AIDS | Oral | 1992 | Ireland | This study |

| CD509 | + | Oral | 1992 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD510 | AIDS | Oral | 1994 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD511 | + | Oral | 1995 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD512 | + | Oral | 1995 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD513 | − | Oral | 1995 | Ireland | This study |

| CD514 (B, 11) | − | Oral | 1995 | Ireland | This study |

| CD517 | − | Oral | 1996 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD518 | − | Oral | 1996 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD519 (C, 8) | AIDS | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | This study |

| CD520 | − | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | This study |

| CD521 | + | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD522 | + | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | 39 |

| CD523A (D, 17) | − | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | This study |

| CD523B (D, 3) | |||||

| CD524 | − | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | This study |

| CD525 | − | Oral | 1997 | Ireland | This study |

| CD526 | + | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD527A (E, 15) | AIDS | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD527B (E, 2) | |||||

| CD528 (F, 20) | AIDS | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD529 (G, 18) | AIDS | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD530 | − | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD531 | − | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD532 | − | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD533 | − | Blood | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD536 (H, 10) | − | Oral | 1998 | Ireland | This study |

| CD542 | − | Oral | 1999 | Ireland | This study |

| CD543 | AIDS | Oral | 1999 | Ireland | This study |

| CD2000 | − | Oral | 2000 | Ireland | 1 |

| CD2003 | − | Oral | 2000 | Ireland | 1 |

| CD2004 | − | Oral | 2000 | Ireland | 1 |

| p6265 | − | Sputum | 1999 | Israel | 40 |

| p6785 | − | Urine | 1999 | Israel | 40 |

| p7276 | − | Respiratory tract | 1999 | Israel | 40 |

| p7858 | − | Vagina | 1999 | Israel | This study |

| p7890 | − | Respiratory tract | 1999 | Israel | This study |

| p7852 | − | Vagina | 1999 | Israel | This study |

| p7507 | − | Sputum | 1999 | Israel | This study |

| p7718 | − | Wound | 1999 | Israel | This study |

| CD534 | − | N/A | N/Ab | Japan | 1 |

| CD19398 | + | Oral | 1998 | Norway | 1 |

| CD94191 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD2491 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD94234 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD941026 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD94895 | − | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD94208 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD94924 | + | Oral | 1994 | Spain | 39 |

| CD96104 | − | Oral | 1995 | Spain | 42 |

| Co4 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| Co5 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| Co7 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| P2 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| P7 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| P21 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| P27 | + | Oral | 1993 | Switzerland | 3 |

| NCPF3108 | − | Stool | 1957 | United Kingdom | 57 |

| CD75089 | N/A | Oral | 1973 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD75043 | N/A | Oral | 1975 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD75004 | N/A | Oral | 1975 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD538 | − | Stool | 1986 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD539 | AIDS | Oral | 1994 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD540 | − | Sputum | 1997 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| CD541 | − | Blood | 1997 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| m26b | − | Oral | 1995 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| m262b | − | Oral | 1995 | United Kingdom | 39 |

| m196cd | − | Oral | 1995 | United Kingdom | 39 |

There were multiple isolates of CD507, CD514, CD519, CD523, CD527, CD528, CD529, and CD536. These isolates were recovered from the same oral specimen, in each case, from patients A to H. The patient designation and the number of isolates of each strain examined are indicated in parentheses after the strain name, e.g., CD507 (A, 18) indicates there were 18 isolates of the strain CD507 examined and that this strain came from patient A. Two separate C. dubliniensis strains detected on the basis of Cd25 fingerprint profiles were recovered from patients D and E, and these were termed CD523A and CD523B (patient D) and CD527A and CD527B (patient E). Multiple clonal isolates of strains CBS8500 (six isolates) and CBS8501 (15 isolates) were recovered from various body sites of two separate Dutch patients. Isolates CM1 and CM2 (57) and isolates Can4 and Can6 were both recovered from the same patients at separate clinical evaluations (39). The C. dubliniensis type strain CD36 is lodged with the American Type Culture Collection (accession number MYA-646) and with the British National Collection of Pathogenic Fungi (accession number NCPF 3949). Isolates CBS2747, CBS8500, and CBS8501 are lodged with the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. Ten of the isolates investigated here were included in the Joly et al. study (17), including the seven Cd25 group I isolates CD36, Co4, Co5, CM1, CM2, CM4, and CM6 and the three Cd25 group II isolates CD75089, CD75043, and CD75004. The provenance of specific clusters of isolates highlighted in color in Fig. 1 was as follows: Australian isolates CM1, CM2, CM4, CM5, and CM6, highlighted in dark blue, were from patients at the Fairfield Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria; Canadian isolates Can3, Can4, Can6, and Can9, highlighted in blue, were from patients at the Centre hospitalier de l'Université Laval, Quebec City; Irish isolates CD36, CD38, CD503, CD507, CD522, CD2000, and CD2003, highlighted in green, were from patients at the Dublin Dental Hospital, whereas isolate CD57 was isolated from a patient at St. James's Hospital, Dublin; Spanish isolates CD94924, CD941026, and CD94208, highlighted in red were from patients at the Hospital de Cruces, Bizkaia, Spain, whereas isolate CD94895 was isolated from a patient at the Clínicas Odontológicas, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain.

N/A, not available.

For each population, cells were sampled directly from the site of colonization by plating swab specimens from the mid-dorsum of the tongue onto CHROMagar Candida medium (8, 34). After 48 h of incubation at 37°C, single-colony isolates were presumptively identified as C. dubliniensis on the basis of their dark green coloration (8). Definitive identification was confirmed by the inability of the isolates to grow at 45°C (39) and by their substrate assimilation profiles using the API ID 32C yeast identification system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) as described previously (38). Two of these individuals, patients D and E, each harbored two distinct strains of C. dubliniensis, as determined by DNA fingerprinting analysis (see Results section).

In a separate analysis, serial isolates were recovered from two separate patients in the Netherlands over a defined time period (Table 2) (31). In the first case, a patient receiving chemotherapy for relapsed nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma yielded C. dubliniensis from a variety of anatomic sites (including blood) over a period of 5 months. In the second case, a patient suffering from graft-versus-host disease following an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant also yielded a series of C. dubliniensis isolates in samples taken over a period of 10 days. Following each sampling, isolates were identified as C. dubliniensis on the basis of lack of growth at 45°C, dark green colony color on CHROMagar Candida medium, poor hybridization with the C. albicans fingerprinting probe Ca3, and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprint pattern analysis (31). In each case a single colony was chosen for further analysis.

TABLE 2.

C. dubliniensis serial isolates recovered from various samples from two Dutch patientsa

| Patient no. | Isolate | Date of isolation (day-mo-yr) | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CBS 8501.1 | 26-06-1995 | Oral |

| CBS 8501.2 | 17-07-1995 | Bronchial | |

| CBS 8501.3 | 25-07-1995 | Fecal | |

| CBS 8501.4 | 4-08-1995 | Oral | |

| CBS 8501.5 | 7-08-1995 | Sputum | |

| CBS 8501.6 | 11-08-1995 | Oral | |

| CBS 8501.7 | 13-08-1995 | Fecal | |

| CBS 8501.8 | 13-08-1995 | Blood | |

| CBS 8501.9 | 13-08-1995 | Blood | |

| CBS 8501.10 | 13-08-1995 | Blood | |

| CBS 8501.11 | 14-08-1995 | Oral | |

| CBS 8501.12 | 14-08-1995 | Oral | |

| CBS 8501.13 | 18-08-1995 | Oral | |

| CBS 8501.14 | 19-08-1995 | Wound | |

| CBS 8501.15 | 21-11-1995 | Oral | |

| 2 | CBS 8500.1 | 8-01-1996 | Fecal |

| CBS 8500.2 | 12-01-1996 | Ascites | |

| CBS 8500.3 | 12-01-1996 | Blood | |

| CBS 8500.4 | 15-01-1996 | Blood | |

| CBS 8500.5 | 15-01-1996 | Blood | |

| CBS 8500.6 | 18-01-1996 | Blood |

Serial isolates were recovered from two separate patients in the Netherlands (31). Patient 1 yielded C. dubliniensis from a variety of anatomic sites over a period of 5 months while receiving chemotherapy for relapsed nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma. Patient 2 also yielded C. dubliniensis over a period of 10 days while suffering from graft-versus-host disease following an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Isolates were routinely cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Oxoid) medium, pH 5.6, at 37°C. For liquid culture, isolates were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth at 37°C in an orbital incubator (Gallenkamp, Leicester, United Kingdom) at 200 rpm.

Chemicals, enzymes, radioisotopes, and oligonucleotides.

Analytical-grade or molecular biology-grade chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Ireland Ltd. (Tallaght, Dublin, Ireland), BDH (Poole, Dorset, United Kingdom), or Roche Diagnostics Ltd. (Lewes, East Sussex, United Kingdom). Enzymes were purchased from the Promega Corporation (Madison, Wis.) and from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. [α-32P]dATP (6,000 Ci mmol−1; 222 TBq mmol−1) was purchased from Amersham International Plc. (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). Custom-synthesized oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Genosys Biotechnologies (Europe) Ltd. (Pampisford, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom).

Hybridization analysis and computer-assisted analysis of DNA fingerprint profiles.

Southern blot hybridization of restriction endonuclease-digested genomic DNA from C. dubliniensis isolates was performed as described previously (57). EcoRI-digested DNA was electrophoresed through 0.65% (wt/vol) agarose gels for 16 h at 65 V and transferred by capillary blotting to nylon membrane filters (Osmonics, Westborough, Mass.) as described by Sullivan et al. (57). Hybridization reactions were carried out under high-stringency conditions with 32P-labeled probes labeled by random primer labeling (57).

The C. dubliniensis probes Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 were used for fingerprinting isolates of C. dubliniensis. The complex probe Cd25 was used for fingerprinting independent isolates of C. dubliniensis, whereas Cd24 and Cd1 were used to assess microevolution within individual strains (17). Computer-assisted analyses of hybridization patterns were performed using the DENDRON software package version 2.3 (Solltech, Iowa City, Iowa) as described previously (17, 51, 52). DNA from the C. dubliniensis isolate CM6 (57) was used as a reference on each gel used for computer-assisted analysis. Similarity coefficients (SABs) based on band position alone were calculated for each pairwise combination of isolate patterns according to the formula SAB = 2E/(2E + a + b), where E is the number of bands shared by strains A and B, a is the number of bands unique to A, and b is the number of bands unique to B (52). An SAB of 0.0 represents totally different patterns with no correlated bands, an SAB of 1.00 represents identical patterns, and SABs ranging from 0.01 to 0.99 represent patterns with increasing proportions of bands at the same positions.

PCR amplification.

The ITS1/ITS4 primer pair (Table 3) was used to amplify the internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 (ITS1 and ITS2, respectively) regions and the intervening 5.8S rRNA gene of C. dubliniensis isolates. These primers are complementary to conserved regions of the fungal 18S and 28S rRNA genes, respectively, which flank the ITS1 and ITS2 regions (62). Specific restriction endonuclease cleavage sites were incorporated into the primers to facilitate cloning of amplified products (Table 3). PCR amplifications were performed using the High Fidelity PCR System (Roche, Lewes, East Sussex, United Kingdom) following the recommendations of the manufacturer. In brief, each 100-μl reaction contained 1× Expand High Fidelity buffer; dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP at 200 μM each; 2.6 U of Expand High Fidelity PCR System enzyme mix; 300 nM ITS1 and 300 nM ITS4; 1.5 mM MgCl2; and 100 ng of template DNA. Amplification reactions were carried out in a Perkin Elmer Cetus DNA thermal cycler with initial denaturation for 3 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 58°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. Following amplification, the amplimers were purified using a Promega PCR extraction kit and cloned into pBlusescript II KS(−) by conventional methods (47).

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide sequence of PCR primers used to amplify specific regions of C. dubliniensis DNA

| Primer | Sequencea | Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS1 | 5"-CGGAATTCTCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3" | Forward primer for amplifying the ITSb region | 62 |

| ITS4 | 5"-CGGAATTCTCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying the ITS region | 62 |

| G1F | 5"-TTGGCGGTGGGCCCCTG-3" | Forward primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 1 isolates | This study |

| G1R | 5"-AGCATCTCCGCCTTATA-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 1 isolates | This study |

| G2F | 5"-CGGTGGGCCTCTACC-3" | Forward primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 2 isolates | This study |

| G2R | 5"-CATCTCCGCCTTACC-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 2 isolates | This study |

| G3F | 5"-TTGGTGGTGGGCTTCTG-3" | Forward primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 3 isolates | This study |

| G3R | 5"-GCAATCTCCGCCTTACC-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 3 isolates | This study |

| G4Fc | 5"-GGCCTCTGCCTGCCGCCAGAGGATG-3" | Forward primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 4 isolates | This study |

| G4Rc | 5"-AGCAATCTCCGCCTTACT-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying approx. 330 bp of the ITS region from genotype 4 isolates | This study |

| RNAF | 5"-GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGAAAAG-3" | Forward primer for amplifying approx. 610 bp of the large ribosomal subunit gene, used here as an internal positive control in genotype-specific PCR | 13 |

| RNAR | 5"-GGTCCGTGTTTCAAGACG-3" | Reverse primer for amplifying approx. 610 bp of the large ribosomal subunit gene, used here as an internal positive control in genotype-specific PCR | 13 |

Underlining indicates EcoRI restriction enzyme sites incorporated into the primer to facilitate cloning.

The ITS includes ITS1, 5.8S rRNA gene, and ITS2. The locations of the various GF and GR primer sequences within the ITS region are shown in Fig. 2a.

The G4F and G4R primers each differed from the ITS genotype 4 sequence (shown in Fig. 2a) by a single base-pair change at the 3" end to improve specificity.

PCR identification of isolates belonging to C. dubliniensis genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4 was performed using the primer pairs G1F/G1R, G2F/G2R, G3F/G3R, and G4F/G4R, respectively (Table 3). These primers were designed based on observed differences in the nucleotide sequence of the ITS1 and ITS2 regions of isolates belonging to each of the four C. dubliniensis genotypes (see Results section). The genotype 4-specific forward and reverse primers were designed with a base mismatch at their 3" ends to increase their specificity (Table 3) (13). Each PCR was carried out with one pair of these genotype-specific primers and the universal fungal primers RNAF/RNAR (13), which amplify approximately 610 bp from all fungal large-subunit rRNA genes and were used as an internal positive control.

PCR was carried out using Taq DNA polymerase (Promega). Each 100-μl PCR for genotypes 1, 2, and 3 contained 1× reaction buffer; dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP at 200 μM each; 2.5 U of Taq polymerase; a 300 nM concentration of each primer; 1.5 mM MgCl2; and either 100 ng of purified template DNA or rapidly prepared template DNA obtained by boiling yeast cells. Template DNA obtained by the latter method was prepared by boiling a single 48-h-old PDA-grown colony in 50 μl of sterile ultrapure H2O for 10 min. After boiling, the debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the DNA contained in 25 μl of the supernatant was used as the template for subsequent PCRs. The PCR cycling conditions were initial denaturation for 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 20 s at 72°C, and a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. Optimum conditions for genotype 4-specific PCR were determined empirically. These were as above except that 20 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) were used and the annealing temperature was 55°C.

Following PCR, 5-μl aliquots of the amplification mixture from genotype 1-, 2-, and 3- specific PCRs and 10 μl of the amplification mixture from genotype 4-specific PCR were separated by electrophoresis through 2.4% (wt/vol) agarose gels containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml and were visualized on a UV transilluminator. Due to the lower dNTP concentration, less PCR product is produced in the genotype 4-specific PCR compared to the other three genotype-specific PCRs.

DNA sequencing.

Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed by the dideoxy chain-terminating method of Sanger et al. (48) using an automated Applied Biosystems 377 DNA sequencer and dye-labeled terminators (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The sequencing primers used were the M13 forward and reverse primers. Sequence alignments were carried out using the Clustal W sequence analysis computer software package (59).

Karyotype analysis.

Yeast chromosomes were prepared in agarose plugs by the method of Vazquez et al. (60) and resolved in 1.4% (wt/vol) agarose gels by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis using the CHEF-Mapper system (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome preparations (Bio-Rad) were included on each gel as reference standards. The electrophoresis buffer used was 1× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) (47) and was maintained at 14°C using buffer recycling through a Bio-Rad minichiller (model 1000). Gels were electrophoresed at 4 V/cm for 72 h with an initial switch time of 40 s and a final switch time of 600 s, with a ramping factor of −2.379 and an included angle of 110°. Following electrophoresis, gels were stained with 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml for 15 min, destained in distilled water, and viewed on a UV transilluminator. The C. dubliniensis isolate CD33 (57) was used as a reference isolate for comparing karyotype profiles on different gels.

Exposure of isolates of C. dubliniensis to fluconazole in vitro.

One hundred fluconazole-susceptible colonies of each of the C. dubliniensis strains CD514 and CD36 (Table 1) were inoculated onto yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) agar medium (per liter: 10 g of yeast extract [Oxoid], 20 g of peptone [Difco], 20 g of glucose, and 15 g of Bacto agar [Difco], pH 5.5) containing fluconazole at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. Each colony was then aseptically transferred using sterile toothpicks onto fresh YPD agar containing 0.5 μg of fluconazole per ml and incubated for a further 48 h at 37°C. Each colony was then further subcultured twice as above on YPD agar containing fluconazole at 1, 5, 10, 50, 60, and 70 μg/ml. At 50 μg/ml, derivatives of only 24 of 100 of the CD514 colonies initially selected still grew; 20 of these were selected for further study and termed CD514Flu50 derivatives. At 70 μg of fluconazole per ml, only 13 of 100 of the CD514 colonies still grew; all of these were selected for further study and termed CD514Flu70 derivatives. Derivatives of all 100 CD36 colonies initially selected were obtained which were capable of growing on 70 μg of fluconazole per ml; 20 of these were selected for further study and termed CD36Flu70 derivatives. Similar experiments were also performed with C. dubliniensis CD514 and CD36, which were repeatedly subcultured, as above, but in the absence of fluconazole.

Antifungal susceptibility test methods.

Microdilution susceptibility testing with fluconazole was carried out by the method of Rodriguez-Tudela and Martinez-Suárez on RPMI medium supplemented with 2% (wt/vol) glucose (44), which is a modification of the broth macrodilution method outlined in the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards document M-27P (33). The NCCLS-recommended quality control strains Candida krusei ATCC 6258 and Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 were used (33). Fluconazole powder was a gift from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (Sandwich, Kent, United Kingdom).

RESULTS

DNA fingerprint analysis of a diverse collection of C. dubliniensis isolates.

In order to investigate the range of genetic diversity among C. dubliniensis isolates, a collection of 98 isolates recovered from 94 separate individuals in 15 different countries (Table 1) were fingerprinted with the C. dubliniensis-specific complex probe Cd25. The resulting complex hybridization profiles were subjected to computer-assisted analysis with the fingerprint profile analysis software package DENDRON. Similarity coefficient (SAB) values were computed for every possible pairwise combination of isolates, and these data were used to construct a dendrogram showing the relationships between all of the isolates in the collection (Fig. 1).

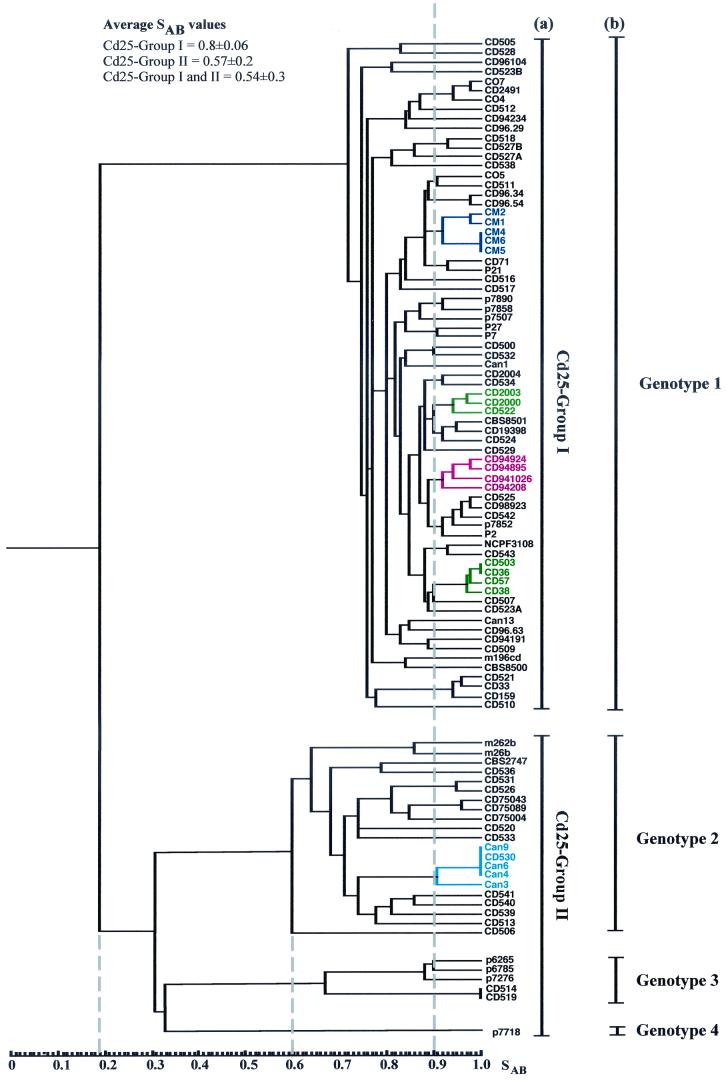

FIG. 1.

Dendrogram generated from the similarity coefficients (SABs) computed for every possible pairwise combination of 98 isolates from 94 patients fingerprinted with Cd25. The origins of the isolates are shown in Table 1. At an SAB of 0.19 (short dashed vertical line), the isolates are divided into two main populations, termed Cd25 groups I and II. At an SAB of 0.6 (short dashed vertical line), four distinct clades are evident; one clade corresponds to Cd25 group I, whereas the other three clades are found within Cd25 group II. Multiple isolates of the same C. dubliniensis strain recovered from the same clinical specimen for each of eight separate individuals yielded SAB values of ≥ 0.93; the SAB value of 0.9 (dashed vertical line) was therefore chosen as an arbitrary threshold value for describing clusters. The cluster of Australian isolates is highlighted in dark blue, two clusters consisting of Irish isolates only are highlighted in green, a cluster of four Spanish isolates is highlighted in red; and a cluster of Canadian isolates and one Irish isolate is highlighted in light blue. The Cd25 groups (a) and the ITS genotypes (b) of the isolates are shown to the right of the dendrogram. All 27 of the Cd25 group II isolates and 43 of 71 of the Cd25 group I isolates had their genotypes determined by genotype-specific PCR.

Examination of the dendrogram revealed that the isolates could be clearly divided by a node at an SAB value of 0.19 into two main populations of isolates. The first population of isolates was designated Cd25 group I (71 isolates), and the second population of isolates was designated Cd25 group II (27 isolates) (Fig. 1). These findings confirm and extend the findings of a previous study with Cd25-generated fingerprint profiles obtained with a collection of 57 independent C. dubliniensis isolates from 11 different countries, in which the isolates were clearly separated into two distinct groups at an SAB node value of 0.24 (17). In the present study, the total collection of isolates had an average SAB value of 0.54 ± 0.30, Cd25 group I isolates had an average SAB value of 0.80 ± 0.06, and the Cd25 group II isolates had an average SAB value of 0.57 ± 0.20. At an SAB threshold value of 0.60, four distinct clades are evident (Fig. 1). Cd25 group I isolates form a distinct clade, whereas Cd25 group II isolates consist of three separate clades.

Multiple isolates of the same C. dubliniensis strain (with identical or very closely related Cd25 fingerprint profiles) recovered from the same clinical specimen for each of eight separate individuals (patients A to H, Table 1) yielded SAB values of ≥0.93 in each case (see below). Closely related clusters of isolates (e.g., SAB values of >0.9) are evident in the dendrogram. While many of these clusters have no obvious significance, in some cases clusters correspond to the hospital of isolation and/or the country of origin of the isolates (Fig. 1 and Table 1). For example, there are two clusters that comprise solely isolates from Dublin, Ireland (highlighted in green in Fig. 1), all of the Australian isolates which were obtained in the same Melbourne hospital clustered closely together (highlighted in dark blue in Fig. 1), four of the Spanish isolates which were obtained in two separate clinics or hospitals clustered together (highlighted in red in Fig. 1), and there is a cluster of Canadian isolates from the same hospital with one Irish isolate (highlighted in light blue in Fig. 1). There are also several examples of pairs of isolates recovered in the same hospital from different patients with an SAB value above 0.9 (Fig. 1), including oral isolates CD75089 and CD75043, (SAB = 0.98), recovered from patients in a hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom, and a pair of Irish oral isolates, CD518 and CD527B (SAB = 0.93), recovered in the Dublin Dental Hospital (Fig. 1).

There were several examples where isolates recovered from separate individuals yielded identical Cd25 fingerprint profiles, suggesting that these individuals harbored identical or very closely related strains. In order to confirm this, these isolates were also fingerprinted by karyotype analysis. Three Australian Cd25 group I isolates (CM4, CM5, and CM6, Fig. 1 and Table 1) yielded identical Cd25 patterns; however, Sullivan et al. previously showed that these isolates yielded distinctly different karyotype patterns with ≥5 band differences (57), suggesting that these isolates are not necessarily the same strain. The Irish Cd25 group I isolates CD36 and CD503 (Fig. 1 and Table 1) yielded identical Cd25 fingerprint patterns and similar karyotype patterns (five karyotype bands in common but differed by three bands), the Irish Cd25 group II isolates CD514 and CD519 also yielded identical Cd25 fingerprint patterns and karyotype patterns. This suggests that the isolates in each pair are the same strain in each case.

In addition, the Canadian isolates Can4, Can6 (both recovered from the same patient at different times), and Can9 and the Irish isolate CD530 (Table 1) yielded identical Cd25 fingerprint patterns (Fig. 1) despite the fact that the isolates were recovered in different countries. The isolates Can4, Can6, and Can9 also yielded identical karyotype patterns, strongly suggesting that they do in fact belong to the same strain. However, the Irish isolate CD530 yielded a very different karyotype pattern (only one karyotype band in common) from the Canadian isolates, suggesting that this isolate, which is epidemiologically unrelated to the Canadian isolates, is highly unlikely to be the same strain.

The majority (48 of 71, 67.6%) of the Cd25 group I isolates were recovered from HIV-infected patients, whereas the majority (19 of 27, 70.4%) of the Cd25 group II isolates were recovered from HIV-negative individuals (these include isolates CD75089, CD75043, and CD75004, which were recovered between 1973 and 1975 from a cardiac unit from patients assumed for the purpose of this study to be HIV negative) (Table 1). Overall, 23 of 27 (85%) of the Cd25 group II isolates were recovered from individuals in Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, or Israel. Eight of the 11 English isolates included in this study belonged to Cd25 group II, and of these, 7 were from HIV-negative individuals. A minority (17 of 98, 17.3%) of the C. dubliniensis isolates in the total collection studied were nonoral isolates, and of these, 8 of 17 (47%) belonged to Cd25 group II.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of C. dubliniensis ITS regions.

In order to determine whether the separation of isolates into Cd25 groups I and II on the basis of Cd25 fingerprint patterns was reflected by differences at the nucleotide sequence level, the nucleotide sequences of the ITS1 and ITS2 regions and the intervening 5.8S rRNA encoding DNA of 19 of the C. dubliniensis isolates analyzed by DNA fingerprinting were determined. The 19 isolates examined (Table 1) included 7 Cd25 group I isolates (CD507, CD33, CD505, CD516, CD2491, P2, and CD96.54) and 12 Cd25 group II isolates (Can6, CD539, CD540, CD75043, CD520, CD506, p7718, CD514, CD519, p6265, p6785, and p7276). These 19 isolates were originally selected because they represented a diverse range of isolates from the four clades observed in Fig. 1, and each yielded a different fingerprint profile with the Cd25 probe, apart from CD514 and CD519, which yielded identical fingerprints.

PCR amplification reactions were performed with template DNA from each of the isolates using the ITS1/ITS4 primer pair (Table 3), which were designed to specifically amplify the ITS region and flanking sequences. Specific restriction endonuclease cleavage sites were incorporated into the primers to facilitate cloning of amplified products (Table 3). A single amplimer of approximately 520 bp was obtained with template DNA from each of the 19 isolates. Amplimer DNA from each isolate was digested with restriction endonucleases and cloned into vector plasmid pBluescript, and the nucleotide sequence of both strands of the cloned insert was determined.

The ITS region (from the first nucleotide of ITS1 to the last nucleotide of ITS2) of the seven Cd25 group I isolates was found to be 453 bp in length, whereas the corresponding ITS region of the 12 Cd25 group II isolates varied between 451 and 452 in length. Four sequence types were observed among the 19 isolates sequenced, and the corresponding isolates were designated genotypes 1 to 4 (Fig. 2a). The seven Cd25 group I isolates sequenced belonged to genotype 1 (ITS region 453 bp long; EMBL database accession no. AJ311895), six of the Cd25 group II isolates sequenced belonged to genotype 2 (ITS region 451 bp long; EMBL database accession no. AJ311896), five of the Cd25 group II isolates sequenced belonged to genotype 3 (ITS region 452 bp long; EMBL database accession no. AJ311897), and the final Cd25 group II isolate sequenced belonged to genotype 4 (ITS region 452 bp long; EMBL database accession no. AJ311898) (Fig. 2a).

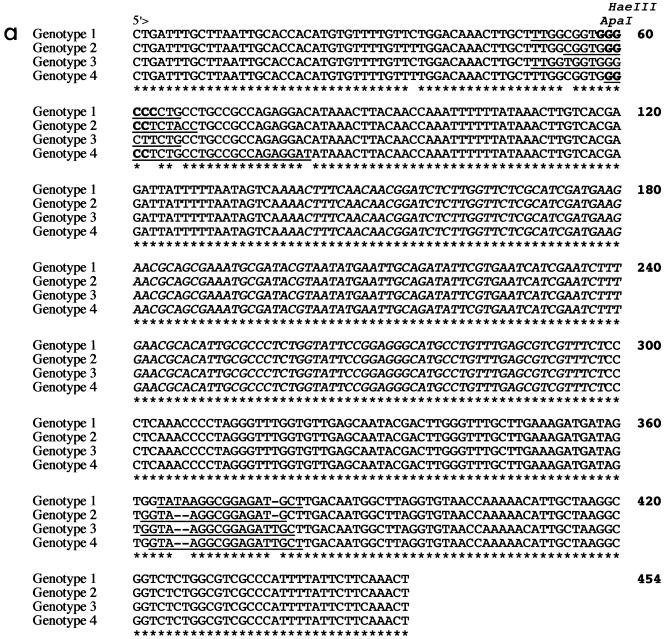

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the sequences of the ITS1, 5.8S rRNA gene, and ITS2 regions of C. dubliniensis strains representative of genotypes 1 (CD33), 2 (CD520), 3 (CD519), and 4 (p7718) generated using the Clustal W software package and a phylogenetic tree generated from the alignment of the ITS sequences (59). Nineteen isolates in total were sequenced, including seven genotype 1 isolates, six genotype 2 isolates, five genotype 3 isolates, and a single genotype 4 isolate. (a), ITS sequence alignment. The central 5.8S rRNA gene sequence is shown in italics, whereas the ITS1 and ITS2 sequences located 5" and 3", respectively, are shown in roman letters. Identical nucleotides are indicated by asterisks, and gaps are indicated by hyphens. Sequence positions of the C. dubliniensis genotype-specific primers G1F/GIR, G2F/G2R, G3F/G3R, and G4F/G4R (Table 2) are underlined. The locations of an ApaI cleavage site (GGGCCC) and a HaeIII cleavage site (GGCC) present only in the genotype 1 sequence and only in the genotype 1, genotype 2, and genotype 4 sequences, respectively, are highlighted in bold. (b) Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree based on ITS sequences. The numbers at the nodes were generated by bootstrap analysis (14) and represent the percentage of times the arrangement occurred in 1,000 randomly generated trees. The scale bar represents 0.02 substitution per site. The ITS sequence of C. albicans was obtained from the GenBank nucleotide sequence database (accession number AB049122). The nucleotide sequences of the ITS regions of the four C. dubliniensis isolates shown in the figure have been deposited in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database as follows: CD33, accession no. AJ311895; CD520, accession no. AJ311896; CD519, accession no. AJ311897; and p7718, accession no. AJ311898.

Genotype 1 isolates differed from genotype 2 isolates at five nucleotide positions, from the five genotype 3 isolates at six nucleotide positions, and from the single genotype 4 isolate at six nucleotide positions (Fig. 2a). Six of the seven genotype 1 isolates examined yielded identical sequences; the remaining isolate exhibited a single base difference (C changed to a T) at nucleotide position 413. Similarly, five of the six genotype 2 isolates examined yielded identical sequences, whereas one isolate showed a single base difference (C changed to a T) at nucleotide position 92. The five genotype 3 isolates yielded identical sequences.

A phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree (45) based on the ITS sequences of the four C. dubliniensis genotypes and C. albicans was generated using Clustal W (Fig. 2b). Each individual C. dubliniensis genotype in this tree corresponds to a distinct clade in the dendrogram shown in Fig. 1. The Cd25 group II isolates separated into three distinct clades in the dendrogram, and these subgroups correspond to ITS genotypes 2, 3, and 4 (Fig. 1). The genotype 3 and 4 isolates separate from the genotype 2 isolates at an SAB node of 0.3. The genotype 4 isolate separated from the genotype 3 isolates at an SAB node of 0.32. Since the order of data input by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean, as used by the Dendron software program, can affect branching and thus affect the stability of clusters in a dendrogram (2), data input was randomized 100 times and 100 separate dendrograms were generated. In these dendrograms, the four genotypes always clustered as four distinct clades (Fig. 1), demonstrating their stability.

Analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the ITS region of genotypes 1 to 4 indicated differences in the presence or absence of specific restriction endonuclease cleavage sites (Fig. 2a). Thus, there is a unique ApaI restriction enzyme site present in the genotype 1 sequence only. A unique HaeIII restriction site is present in the sequences from genotypes 1, 2, and 4 which is absent in the corresponding genotype 3 sequence (Fig. 2a). The presence of these restriction enzyme cleavage sites can be used to distinguish genotypes 1 and 3 by digestion of the 520-bp ITS amplimers generated with the ITS1/ITS4 primers (data not shown). However, genotypes 2 and 4 cannot be distinguished from each other based on these restriction sites (Fig. 2a).

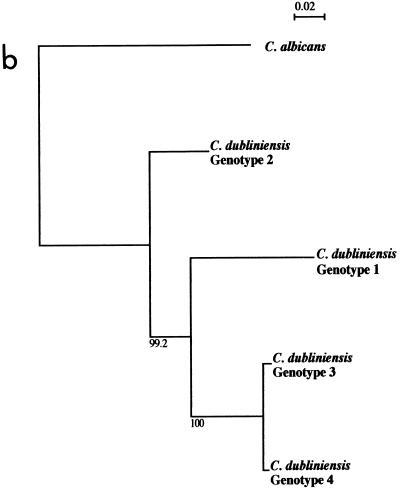

In order to be able to rapidly identify C. dubliniensis isolates belonging to each of the four genotypes determined by ITS region sequencing, genotype-specific primer pairs were designed based on nucleotide sequence differences observed in the ITS1 and ITS2 regions (Fig. 2, Table 3). Each genotype-specific primer pair was used separately to amplify a DNA fragment of approximately 330 bp from C. dubliniensis template DNA from each of 43 genotype 1 isolates (Cd25 group I isolates), all 21 genotype 2 isolates, all five genotype 3 isolates, and the single genotype 4 isolate. PCRs also contained the fungal universal primers RNAF/RNAR (13), which amplify a product of approximately 610 bp from the fungal large-subunit rRNA gene and serve as an internal positive control. While all C. dubliniensis isolates should produce a product of approximately 610 bp with the RNAF/RNAR primers, only C. dubliniensis isolates belonging to the correct genotype should yield a product of approximately 330 bp with the appropriate genotype-specific primer pair.

All 70 C. dubliniensis isolates tested yielded the 610-bp product resulting from amplification with the fungal universal primers. However, only the 43 genotype 1 isolates tested yielded a product of approximately 330 bp with the genotype 1 primer pair (G1F/G1R) (Fig. 3). Similarly, only the 21 genotype 2 isolates yielded a product of approximately 330 bp with the genotype 2 primer set (G2F/G2R), only the five genotype 3 isolates yielded a product of approximately 330 bp with the genotype 3 primer set (G3F/G3R), and only the single genotype 4 isolate yielded a product of approximately 330 bp with the genotype 4 primer set (G4F/G4R) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel showing ethidium bromide-stained amplimers (approximately 330-bp products) from PCRs with C. dubliniensis genotype-specific primer sets G1F/G1R (lanes 2 to 5), G2F/G2R (lanes 6 to 9), G3F/G3R (lanes 10 to 13), and G4F/G4R (14 to 17) and the fungal universal primers RNAF and RNAR (610-bp product). The amplimers shown in the lanes were obtained from template DNA from C. dubliniensis isolates as follows: lanes 2, 6, 10, and 14, CD505 (genotype 1); lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15, CD536 (genotype 2); lanes 4, 8, 12, and 16, CD514 (genotype 3); and lanes 5, 9, 13, and 17, p7718 (genotype 4). Lanes 1 and 19, molecular size reference markers (100-bp ladder); lane 18, negative control reaction lacking template DNA but including RNAR and RNAF primers.

Karyotype analysis of C. dubliniensis isolates.

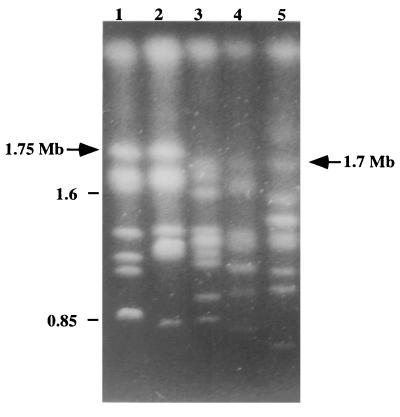

Eighty-eight of the C. dubliniensis isolates fingerprinted with the Cd25 probe were also investigated by karyotype analysis, including 65 Cd25 group I isolates and 23 Cd25 group II isolates (including 17 ITS genotype 2 isolates, the 5 ITS genotype 3 isolates, and the single ITS genotype 4 isolate). All 23 Cd25 group II isolates tested had a chromosome-sized DNA band of approximately 1.7 Mb present in their karyotype profiles that was absent in the corresponding profiles of all but 5 (5 of 65, 7.6%) of the Cd25 group I isolates tested. Furthermore, the majority (60 of 65, 92.3%) of the Cd25 group I isolates tested had a chromosome-sized DNA band of approximately 1.75 Mb present in their karyotype profiles that was absent in the corresponding profiles of all 23 Cd25 group II isolates tested (Fig. 4). A 1.7-Mb band was also present in the five Cd25 group I isolates lacking the band of approximately 1.75 Mb.

FIG. 4.

Karyotype analysis of C. dubliniensis isolates. The karyotypes shown correspond to C. dubliniensis genotype 1 isolates CD33 (lane 1) and CD94924 (lane 2) and genotype 2 isolates Can6 (lane 3), Can3 (lane 4), and CD541 (lane 5). The position of a chromosome-sized band of approximately 1.75 Mb present in the genotype 1 isolate profiles but absent in genotype 2 isolate profiles is indicated by an arrow. The position of a chromosome-sized band of approximately 1.7 Mb present in the genotype 2 isolate profiles but absent in the majority of genotype 1 isolate profiles is also indicated by an arrow. Genotypes 3 and 4 lacked a band at 1.75 Mb and, like the genotype 2 isolates, had a band at approximately 1.7 Mb (data not shown). The relative positions of molecular size reference markers (in megabases) are shown on the left.

In vivo microevolution in populations of C.

dubliniensis. (i) Genetic variation in multiple isolates of C. dubliniensis from the same clinical specimen. To assess the genetic relatedness of populations of C. dubliniensis isolates from particular individuals, multiple single-colony isolates recovered from the same oral specimen from each of eight separate patients attending the Dublin Dental Hospital, either with (patients A, C, D, and E, Table 1) or without (patients B, F, G, and H, Table 1) signs of oral candidiasis, were fingerprinted with the complex probe Cd25. All of the isolates tested from six of eight patients studied (patients A, B, C, F, G, and H, Table 1) were found to be clonal in each case (mean SAB for isolates in each population, >0.93) (Table 4). Patients D and E were each found to harbor two separate strains of C. dubliniensis, based on the Cd25 fingerprint profiles obtained (examples from patient D are shown Fig. 5A). The SAB values calculated for the two different strains present in patients D (strains CD523A and CD523B, Table 1) and E (strains CD527A and CD527B, Table 1) were 0.76 and 0.80, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Variability in DNA fingerprint and karyotype profiles in eight clonal populationsa of C. dubliniensis isolates detected with the Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 probes and by karyotype analysis

| Patient | Strainb | Probe or karyotype analysis | No. of isolates tested | Avg SABc | No. of isolates with the predominant pattern | No. of isolates with a minor pattern | No. of minor patterns | Band differences in minor patternsd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | CD507 (I, 1) | Cd25 | 18 | 0.987 ± 0.021 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 1(−1), 1(−1), 1(+1) |

| Cd24 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 3(+1,−1), 4(+1,−1), 1(+1), 1(+2,−2), 1(+2,−1) | ||||

| Cd1 | 0 | 18 | 18 | All 18 isolates had a different pattern | ||||

| Karyotype | 5 | 13 | 6 | 3(+1,−1), 1(−1), 2(+1,−2), 5(−1), 1(+1,−2), 1(+2,−1) | ||||

| B | CD514 (II, 3) | Cd25 | 11 | 1.00 | 11 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Cd24 | 11 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| Cd1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| Karyotype | 11 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| C | CD519 (II, 3) | Cd25 | 8 | 1.00 | 8 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Cd24 | 8 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| Cd1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| Karyotype | 8 | 0 | 0 | None | ||||

| De | CD523A (I, 1) | Cd25 | 17 | 0.937 ± 0.072 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 2(+3), 1(+3,−1), 1(+1), 1(+1,−1) |

| Cd24 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 1(+1), 1(+3,−2), 1(−1) | ||||

| Cd1 | 4 | 13 | 11 | 3(−1), 1(+2,−2), 1(−1), 1(−1), 1(−1), 1(−1), 1(+1,−3), 1(+3,−2), 1(+2,−1), 1(+3,−2), 1(+1,−1) | ||||

| Karyotype | 16 | 1 | 1 | 1(+3, −2) | ||||

| Ee | CD527A (I, 1) | Cd25 | 15 | 0.985 ± 0.028 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 1(+1,−2), 1(+1) |

| Cd24 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 4(−1), 1(−2) | ||||

| Cd1 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 5(−1) | ||||

| Karyotype | 3 | 12 | 9 | 1(+1,−1), 2(+1,−1), 3(+2,−1), 1(+3,−2), 1(+3,−2), 1(+3,−2), 1(+3,−3), 1(+2,−1), 1(+2,−2) | ||||

| F | CD528 (I, 1) | Cd25 | 20 | 0.992 ± 0.011 | 17 | 3 | 1 | 3(+1) |

| Cd24 | 8 | 12 | 2 | 7(−1), 5(+2,−1) | ||||

| Cd1 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 1(+1,−2), 3(+1,−1), 3(+1,−1), 2(+1,−2), 1(+2,−1), 1(+1,−1) | ||||

| Karyotype | 9 | 11 | 3 | 5(+1), 4(+1), 2(+3,−1) | ||||

| G | CD529 (I, 1) | Cd25 | 18 | 0.994 ± 0.016 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) |

| Cd24 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1,−1) | ||||

| Cd1 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 2(−1), 3(−1), 3(+1,−1), 2(+1,−1), 1(+1,−2), 2(+2,−1) | ||||

| Karyotype | 13 | 5 | 4 | 1(+1), 1(+1), 2(+1,−1), 1(+1,−1) | ||||

| H | CD536 (II, 2) | Cd25 | 10 | 1.00 | 10 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Cd24 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) | ||||

| Cd1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1(+1,−3), 2(+1), 1(+1,−1), 1(−1) | ||||

| Karyotype | 10 | 0 | 0 | None |

Multiple single-colony isolates recovered from the same oral specimen for each of eight individuals were investigated.

The Cd25 group (I or II) and the genotype (1, 2, or 3) to which each strain belongs are indicated in parentheses.

Similarity coefficient (SAB) values were calculated from the Cd25-generated hybridization patterns for all possible combinations of isolate pairs in each population using the DENDRON software package. The mean average SAB value for the isolates in each population is shown.

Each variant pattern was assessed according to the number of bands differing from the predominant pattern, e.g., (+1), a band addition; (−1), a band loss; (+1, −1), a band addition and a band loss. Numbers in front of the parentheses refer to the number of isolates with the particular variant pattern, e.g., 2(+2, −1) indicates that two isolates had the same pattern that differed from the predominant pattern by the addition of two bands and the loss of one band.

Patients D and E were each found to harbor two distinct strains of C. dubliniensis on the basis of Cd25 fingerprint profiles, one of which predominated in each case. The C. dubliniensis isolate population from patient D studied consisted of 17 isolates of strain CD523A and 3 isolates of strain CD523B (Table 1), whereas the C. dubliniensis isolate population studied from patient E consisted of 15 isolates of strain CD527A and 2 isolates of strain CD527B (Table 1). None of the CD523B or CD527B isolates showed variation in fingerprint patterns with any of the three probes used, and only one isolate of CD523B showed a minor variation in karyotype profile (data not shown).

None of the isolates tested from patients B, C, and H yielded any variants with the Cd25 probe (for each population, the mean SAB was 1; Table 4). However, minor hybridization band differences were observed in the profiles of the clonal isolates from patients A, F, and G (mean SAB of 0.987 ± 0.021, 0.992 ± 0.011, and 0.994 ± 0.016, respectively) and in the profiles of the isolates of the most abundant strain in each case from patients D and E (mean SAB of 0.937 ± 0.072 and 0.985 ± 0.028, respectively) (Fig. 5A, Table 4). No variation in the Cd25 fingerprint profiles of the minority strains from patient D (strain CD523B, three isolates) or E (strain CD527B, two isolates) was observed.

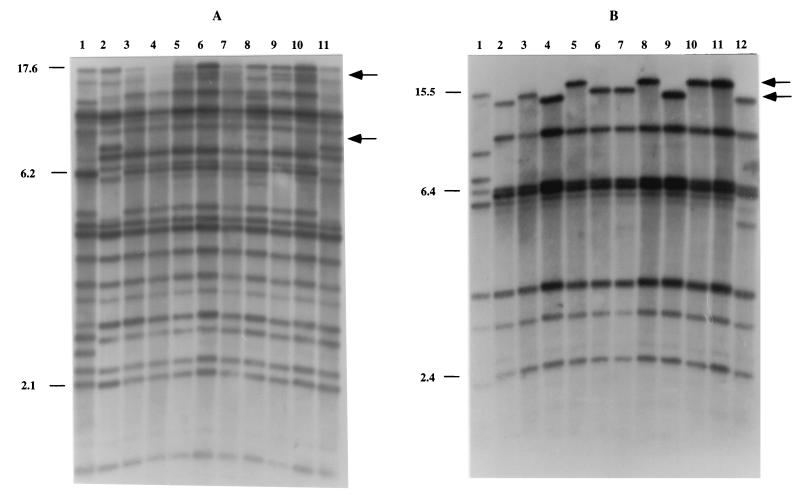

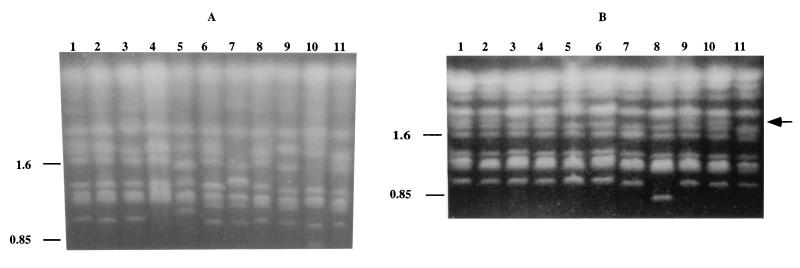

FIG. 5.

DNA fingerprinting patterns of multiple C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from the same clinical specimen from patients A and D. (A) Probe Cd25-generated hybridization patterns of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from 10 single-colony isolates of C. dubliniensis from patient D (Table 1). This patient harbored two distinct strains of C. dubliniensis, termed CD523A and CD523B. Lane 1, C. dubliniensis reference strain CM6 (57); lane 2, CD523B isolate 1; lanes 3 to 10, CD523A isolates 1 to 8, respectively; lane 11, CD523B isolate 2. Examples of polymorphisms in the profiles of CD523A isolates are indicated by arrows. (B) Probe Cd24-generated hybridization patterns of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA from 11 single-colony isolates of C. dubliniensis from patient A. This patient harbored a single strain of C. dubliniensis (CD507 isolate series, Table 1). Lane 1, C. dubliniensis reference strain CM6; lanes 2 to 12, CD507 isolates 1 to 11, respectively. Polymorphisms in the profiles are indicated by arrows. The relative positions of molecular size reference markers (in kilobases) are shown on the left of the panels.

Joly et al. (17) previously reported that the Cd1 and Cd24 C. dubliniensis fingerprinting probes were superior to Cd25 for assessing variability within a strain over time. In the present study, Cd1 and Cd24 were used separately to fingerprint the clonal populations from patients A to H. Using these probes, minor band variation, or microevolution, was observed in the populations from patients A, D, E, F, and G, as also seen with Cd25, but in addition, microevolution was also observed in the population from patient H but not in the populations from patients B and C (Table 4). Furthermore, the hybridization patterns obtained with probes Cd24 and Cd1 readily distinguished the two strains detected in the population of isolates from patients D and E using the Cd25 probe (data not shown). Figure 5B shows examples of the variability detected among clonal isolates from patient A with the Cd24 probe. As with Cd25, no variation in the Cd24 and Cd1 fingerprint profiles of the minority strains of patient D (strain CD523B, three isolates) and E (strain CD527B, two isolates) was observed.

Isolates from each of the populations recovered from patients A to H were also examined by karyotype analysis. Variation in the karyotype profile was observed in the same isolate populations that exhibited microevolution using Cd25 (patients A, D, E, F, and G) but not in the populations from patients B, C, and H (Table 4). Furthermore, the karyotype patterns obtained also distinguished the two strains detected in the population of isolates from patients D (data not shown) and E using the Cd25 probe (Fig. 6, lanes 1 and 2). The clonal isolates belonging to the majority strain from patient E (strain CD527A, Table 1) showed the greatest variability in karyotype pattern, with nine different patterns detected in 15 isolates examined (Table 4), examples of which are shown in Fig. 6, lanes 2 to 8. Variability was observed in the karyotype pattern of one of the three isolates of the minority strain of patient D (data not shown), although no variability was observed in the minority strain of patient E (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Variability in karyotype profiles of multiple C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from the same clinical specimen from patient E (CD527 isolate series, Table 1). This patient harbored two distinct strains of C. dubliniensis, termed CD527A and CD527B. Lane 1, CD527B isolate 1; lanes 2 to 8, CD527A isolates 1 to 7, respectively. An example of a karyotype polymorphism at approximately 0.85 Mb is indicated by an arrow. The relative positions of molecular size reference standards (in megabases) are indicated on the left of the panel.

The isolates from patients A to D and F to H were all susceptible to fluconazole (≤8 μg/ml), while the isolates from patient E (CD527) varied in their susceptibility to fluconazole. Four of the 15 isolates of the predominant strain from patient E (CD527A) had reduced susceptibility to fluconazole (MIC, 16 μg/ml), whereas the remaining 11 isolates were susceptible to fluconazole (MIC, ≤1 μg/ml). The four isolates with reduced susceptibility to fluconazole and one isolate that was susceptible to fluconazole (MIC, 1.0 μg/ml) had Cd24 and Cd1 patterns which differed from the patterns of the remaining 10 susceptible isolates. The karyotype profiles of the four isolates with reduced susceptibility to fluconazole and one isolate that was susceptible to fluconazole (MIC, 1.0 μg/ml) all lacked a band at approximately 0.85 Mb (Fig. 6, lanes 5 to 8) that was present in the remaining 10 susceptible isolates (Fig. 6, lanes 2 to 4). The two isolates from the minority strain from patient E (CD527B) were susceptible to fluconazole (MIC, 1 μg/ml).

(ii) Genetic variation in serial isolates of C. dubliniensis.

Serial isolates of C. dubliniensis from two separate patients were also fingerprinted. These two cases of systemic infection caused by C. dubliniensis were recently reported by Meis et al. (31). For one of the patients concerned, samples were taken from a variety of anatomic locations, including oral, bronchial, fecal, wound, and blood samples, during a 5-month period (Table 2). The first sample was taken from the oral cavity, which had signs of oral candidosis. Other samples (including sputum, fecal, oral, and wound samples) were subsequently taken during the following 5 months for surveillance purposes. Blood samples were also taken when the patient had a fever, which was refractory to antibiotic therapy, suggesting a possible fungal infection. C. dubliniensis was recovered in combination with C. albicans from all of the samples, with the exception of the blood cultures, which yielded C. dubliniensis only.

In each case, a single C. dubliniensis colony was taken from the primary isolation plate and fingerprinted. Using the Cd25 probe, all 15 isolates recovered from different clinical samples yielded very similar fingerprint patterns (average SAB = 0.98 ± 0.03) belonging to Cd25 group I, suggesting that the candidemia was endogenously acquired. Fingerprinting using the probes Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 (data not shown) and karyotype analysis (Fig. 7) revealed the presence of minor polymorphisms indicative of microevolution.

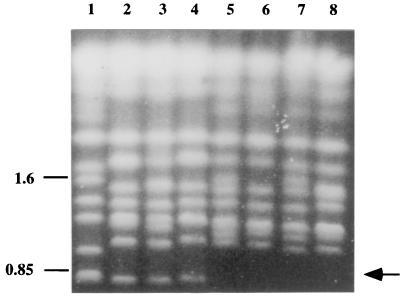

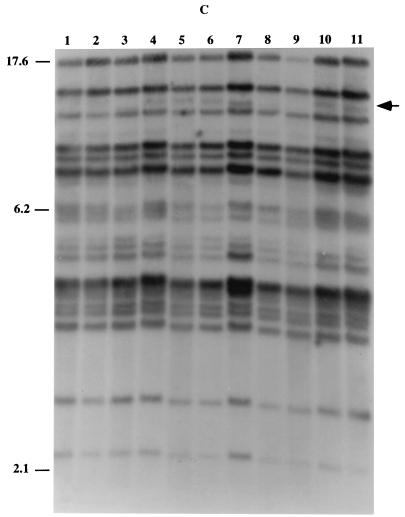

FIG. 7.

Karyotype profiles of 14 serial clonal isolates of C. dubliniensis strain CBS8501 recovered from different anatomic sites of a single Dutch patient (Table 2). Lane 1, CBS 8501.1 (oral); lane 2, CBS 8501.2 (bronchial); lane 3, CBS 8501.3 (fecal); lane 4, CBS 8501.4 (oral); lane 5, CBS 8501.5 (sputum); lane 6, CBS 8501.6 (oral); lane 7, CBS 8501.7 (fecal); lane 8, CBS 8501.8 (blood); lane 9, CBS 8501.9 (blood); lane 10, CBS 8501.10 (blood); lane 11, CBS 8501.12 (oral); lane 12, CBS 8501.13 (oral); lane 13, CBS 8501.14 (wound); and lane 14, CBS 8501.15 (oral). An arrow indicates the position of polymorphisms. The relative position of molecular size reference standards (in megabases) are indicated on the left of the panel.

In a second patient, C. dubliniensis isolates were recovered from four blood, one fecal, and one ascites sample taken over a period of 10 days. All six isolates were found to belong to a single Cd25 group I strain using the Cd25 probe. Fingerprinting with the Cd25 (average SAB = 0.99 ± 0.02) and Cd1 probes and karyotype analysis showed that there were minor variants present; however, no variation was observed with the Cd24 probe (data not shown).

In vitro microevolution in clonal populations of C. dubliniensis exposed to fluconazole.

It has previously been shown that fluconazole resistance can be induced in C. dubliniensis by in vitro exposure to the drug (32). In a similar experiment, 20 fluconazole-resistant (MIC, 64 μg/ml) derivatives of the Cd25 group I (ITS genotype 1) C. dubliniensis strain CD36, termed CD36Flu70, were obtained by repeated subculture of the fluconazole-susceptible (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) parental isolate on agar medium containing increasing concentrations of drug (range, 0.5 to 70 μg/ml). All 20 resistant derivatives grew well on medium containing 70 μg of fluconazole per ml.

Twenty control derivatives, termed CD36(control), were simultaneously repeatedly subcultured on agar medium without fluconazole. These CD36Flu70 and CD36(control) derivatives were tested for microevolution by hybridization analysis with the Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 probes and by karyotype analysis. A single variant (Table 5) was detected in the hybridization patterns of the 20 CD36Flu70 derivatives with the Cd25 probe while no variants were observed in the control derivatives (Table 5). Three variants (Table 5) were detected in the hybridization patterns of the CD36Flu70 derivatives with the Cd24 probe while only one variant (Table 5) was observed with the control derivatives. Variability was observed in the Cd1 hybridization patterns in both the fluconazole-resistant and control derivatives (data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Variability in DNA fingerprint and karyotype profiles in clonal derivatives of two C. dubliniensis strains repeatedly subcultured in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of fluconazolea

| C. dubliniensis derivatives | No. of derivatives analyzed | Fingerprinting method | No. of isolates with the parental pattern | No. of isolates with a minor pattern | No. of minor patterns | Band differences in minor patternsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD36Flu70 | 20 | Cd25 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) |

| Cd24 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 2(−3), 1(+1) | ||

| Karyotype | 10 | 10 | 6 | 1(−1), 1(+2,−2), 1(+2,−3), 4(+1,−1), 1(+1, −2), 2(−1) | ||

| CD36(control) | 20 | Cd25 | 20 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Cd24 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1(+2,−1) | ||

| Karyotype | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1,−1) | ||

| CD514Flu50 | 20 | Cd25 | 6 | 14 | 10 | 1(+1), 1(+1), 1(+1), 1(+1), 2(+1,−1), 2(+1,−1), 3(−1), 1(+1,−1), 1(+1,−1), 1(−1) |

| Cd24 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1(−1) | ||

| Karyotype | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1(+1) | ||

| CD51450(control) | 20 | Cd25 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 1(+1), 1(+1) |

| Cd24 | 20 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Karyotype | 20 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| CD514Flu70 | 13 | Cd25 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 3(+1,−1), 1(−1), 1(+1,−3), 1(−2), 3(−2) |

| Cd24 | 13 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Karyotype | 13 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| CD51470(control) | 13 | Cd25 | 13 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Cd24 | 13 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Karyotype | 13 | 0 | 0 | None |

Twenty fluconazole-resistant (MIC, 64 μg/ml) derivatives of the Cd25 group I C. dubliniensis strain CD36, which were obtained by repeated subculture of the fluconazole-susceptible (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) parental isolate on agar medium containing increasing concentrations of drug (range, 0.5 to 70 μg/ml), were tested for microevolution by hybridization analysis with the Cd25 probe and Cd24 probe and by karyotype analysis. All 20 resistant derivatives grew well on medium containing 70 μg of fluconazole per ml and were termed CD36Flu70 derivatives. Twenty control derivatives which were simultaneously repeatedly subcultured on agar medium without fluconazole were also tested; these were termed CD36(control) derivatives. Variability in the presence or absence of a chromosome-sized band at approximately 1.65 Mb was observed in the karyotype patterns in both the fluconazole-resistant and the control derivatives, and therefore only variability in other chromosomal bands was assessed for microevolution. In similar experiments with the Cd25 group II (genotype 3) C. dubliniensis isolate CD514, it proved more difficult to generate fluconazole-resistant derivatives. However, 20 derivatives that were recovered from agar plates containing 50 μg of fluconazole per ml (CD514Flu50 derivatives) and 13 derivatives that were recovered from plates containing 70 μg of fluconazole per ml (CD514Flu70 derivatives) were studied. Control derivatives which were simultaneously repeatedly subcultured on agar medium without fluconazole were also tested; these were termed CD51450(control) and CD51470(control) derivatives.

See Table 4, footnote d.

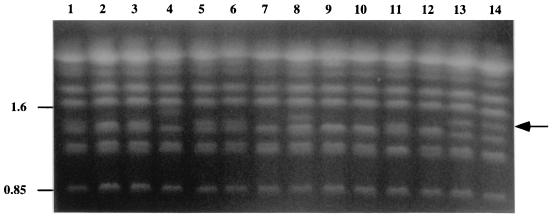

Variability in the presence or absence of a chromosome-sized band of approximately 1.65 Mb was observed in the karyotype patterns in both the fluconazole-resistant and the control derivatives (Fig. 8A and 8B). This band was present in 5 of 20 of the CD36Flu70 derivatives and 11 of 20 of the control derivatives. In addition, 18 separate colonies of the parental CD36 strain from the same PDA plate culture were also fingerprinted by karyotype analysis, and 12 of 18 colonies had a band at approximately 1.65 Mb (data not shown). However, apart from variability in this band at 1.65 Mb, only 1 of 20 of the control derivatives showed variability in other karyotype bands, compared with 10 of 20 of the CD36Flu70 derivatives (Fig. 8A and 8B). These results suggested that exposure of C. dubliniensis CD36 to fluconazole in vitro might be associated with increased levels of genetic variation, manifested as changes in Cd24 fingerprint and/or karyotype profiles, particularly the latter.

FIG. 8.

Karyotype and Cd25 hybridization patterns of isolates of C. dubliniensis exposed to fluconazole in vitro. (A) Karyotype profiles of C. dubliniensis isolate CD36 and derivatives (CD36Flu70) exposed to fluconazole in vitro. Lane 1, C. dubliniensis parental isolate CD36; lanes 2 to 11, CD36Flu70 derivatives. The relative positions of molecular size reference markers (in megabases) are shown on the left of the panel. (B) Karyotype profiles of C. dubliniensis isolate CD36 and CD36(control) derivatives repeatedly subcultured in the absence of fluconazole. Lane 1, C. dubliniensis parental isolate CD36; lanes 2 to 11, CD36(control) derivatives. The arrow indicates the position of a chromosome-sized band of approximately 1.65 Mb which was present in 11 of 20 of the CD36(control) derivatives tested, examples of which are shown here in lanes 2, 4, 9, and 10. The relative positions of molecular size reference markers (in megabases) are shown on the left of the panel. (C) Cd25 hybridization patterns of C. dubliniensis isolate CD514 and derivatives (CD514Flu50)exposed to fluconazole in vitro. Lane 1, C. dubliniensis parental isolate CD514; lanes 2 to 11, CD514Flu50 derivatives. An arrow indicates the position of polymorphisms. The relative positions of molecular size reference markers (in kilobases) are shown on the left of the panel.

In similar experiments using the Cd25 group II (ITS genotype 3) C. dubliniensis isolate CD514, it proved more difficult to generate fluconazole-resistant derivatives. The majority of the 100 colonies plated on increasing concentrations of fluconazole grew very poorly; at 50 μg of fluconazole per ml, only 24 out of the original 100 colonies grew, and at 70 μg of fluconazole per ml, only 13 colonies grew.

Twenty derivatives recovered from agar plates containing 50 μg of fluconazole per ml (CD514Flu50 derivatives) and 13 derivatives recovered from plates containing 70 μg of fluconazole per ml (CD514Flu70 derivatives) were investigated for genetic variation. Most of the CD514Flu50 derivatives and CD514Flu70 derivatives grew poorly on medium containing 50 μg and 70 μg of fluconazole per ml, respectively. Four each of the CD514Flu50 and the CD514Flu70 derivatives exhibited dose-dependent fluconazole susceptibility (MIC, 16 μg/ml), one of the CD514Flu70 derivatives expressed fluconazole resistance (MIC, 64 μg/ml), while all the remaining derivatives were fluconazole susceptible (MIC, <8 μg/ml). No variability was observed in any of the fluconazole-exposed or control derivatives with the Cd1 probe. Variability was observed in one fluconazole-exposed derivative (Table 5) with the Cd24 probe, but no variability was observed in any of the control derivatives (Table 5). However, minor variations were detected in some fluconazole-exposed derivatives with the Cd25 probe, including susceptible derivatives and derivatives with reduced susceptibility (Fig. 8C, Table 5). None of the control derivatives of CD514 which were subcultured in the absence of drug exhibited Cd24 or Cd1 fingerprint or karyotype variations, but two exhibited a minor band variation in the Cd25 fingerprint pattern (Table 5).

One of the fluconazole-exposed derivatives of CD514 exhibited a minor band change in the karyotype profile. It is interesting that when multiple single-colony isolates of CD514 originally recovered from the same clinical specimen (and the identical strain CD519) were examined by Cd25, Cd24, and Cd1 fingerprinting and by karyotype analysis, no variation was detected.

DISCUSSION

Cd25 fingerprint analysis of C. dubliniensis isolates from disparate geographic locations.

Analysis of hybridization patterns generated by complex DNA probes has proven to be one of the most effective methods for investigating the epidemiology of several species of Candida, since it fulfills many of the requirements for performing computer-assisted broad epidemiological studies (12, 18, 24, 50, 51, 52). In 1999 Joly et al. (17) used the moderately repetitive C. dubliniensis-specific DNA fingerprinting probe Cd25 to investigate 57 independent C. dubliniensis isolates and found that the isolates appeared to fall into two distinct populations. One of the purposes of the present study was to investigate the findings of Joly et al. and to examine further the population structure of C. dubliniensis using a larger number of isolates from a broader geographical range than used in the original study.

Ninety-eight isolates of C. dubliniensis from 94 separate individuals obtained from 15 countries around the world were studied, including 10 of the isolates from the study of Joly et al. (17) (Table 1). These were subjected to DNA fingerprinting analysis using the Cd25 fingerprinting probe. Computer-assisted analysis of the fingerprint patterns obtained showed that the isolates separated clearly into two populations corresponding to the two groups described by Joly et al. (17). The first population of isolates was designated Cd25 group I, and the second population was designated Cd25 group II (Fig. 1). A similar form of dichotomy was observed previously in C. albicans by Pujol et al. (41), who used the complex probe Ca3 to distinguish major groups in C. albicans. These groups were subsequently confirmed by Lott et al. (25) using microsatellites and IS1 analysis. In addition, a recent study using the complex C. parapsilosis fingerprinting probe Cp3-13 confirmed the existence of three major subgroups of C. parapsilosis (12), originally suggested on the basis of restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (49), random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (21), karyotype analysis (26), isoenzyme profiles, and ITS sequencing (22).

In the present study, the majority (72%) of the isolates examined belonged to Cd25 group I, with a mean SAB value of 0.80 ± 0.06, indicating that they are very closely related despite being recovered from geographically disparate areas, including North America, South America, Europe, and Israel (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Cd25 group II isolates had a mean SAB of 0.57 ± 0.20 and came from Canada, Ireland, Israel, and England. This value is greater than that observed in the eight group II isolates previously identified by Joly et al. (17) (SAB, 0.47). However, it is evident that there is still significantly greater diversity within the group II population than within the group I population. Joly et al. (17) suggested that the greater variability found among Cd25 group II isolates could be associated with a higher frequency of Cd25 sequence reorganization than in group I isolates or that group I represents a more recent and therefore a more homogeneous subgroup of C. dubliniensis that has become predominant worldwide.

In the strain collection examined in the present study, we observed that 48 of 71 (67.6%) of the Cd25 group I isolates were recovered form HIV-infected patients, while 19 of 27 (70.4%) of the Cd25 group II isolates were recovered from HIV-negative individuals. While these differences are significant (P ≤ 0.001), their epidemiological relevance is not clear. It is possible that the group I isolates are specifically adapted for colonization and survival within the oral cavity and that they have become overrepresented in the human population as a result of the HIV pandemic. However, in order to validate this hypothesis, a much broader epidemiological study will have to be conducted. In the Joly et al. study (17), six of eight (75%) Cd25 group II isolates were from the United Kingdom, suggesting that there may be some reason for the clustering of these isolates in a specific geographical region. However, we did not observe such a geographical bias, with only 8 of 27 group II isolates (30%) originating from the United Kingdom.

In the present study, several sets of C. dubliniensis isolates yielded identical Cd25 patterns. The Irish isolates CD36 and CD503 (Table 1), recovered from separate individuals attending the Dublin Dental Hospital in 1988 and 1989, respectively, gave identical Cd25 fingerprints and highly similar karyotype profiles, indicating that the isolates are closely related. Interestingly, the Irish isolates CD514 and CD519 also yielded identical Cd25 and karyotype patterns, suggesting that they are the same strain, despite the fact they were recovered 2 years apart from separate individuals attending the same hospital as outpatients (Table 1). In contrast, while the Australian isolates CM4, CM5, and CM6, from separate individuals, all had identical Cd25 fingerprint patterns, their karyotype patterns differed significantly, suggesting that they are in fact separate strains. Similarly, the Canadian isolates Can4, Can6, and Can9 and the Irish isolate CD530 all gave identical Cd25 fingerprints. However, while all three Canadian isolates gave identical karyotype profiles, suggesting that they belong to the same strain, the Irish isolate CD530 gave a very different karyotype profile, suggesting that it is unlikely that the Irish and Canadian isolates are epidemiologically related. Therefore, it is possible that Cd25 fingerprint profiling is not sufficiently discriminatory to distinguish among all strains of C. dubliniensis. However, considerable variation can occur in the karyotype profiles within some C. dubliniensis strains due to microevolution (see below), and this could explain why some isolates of the same strain with identical Cd25 fingerprint profiles may exhibit karyotype differences.

A study by Pfaller et al. (37) suggested that individual strains of C. albicans can become established in some hospitals, infecting and colonizing patients, and can subsequently diversify rapidly through microevolution. As described earlier, there appears to be no epidemiological link between the isolates in many of the clusters evident in the dendrogram shown in Fig. 1. However, there are several clusters of closely related C. dubliniensis isolates that were recovered from separate patients attending specific hospitals. The pair of isolates CD36 and CD503 were oral isolates recovered from separate patients at the Dublin Dental Hospital in 1988 and 1989, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 1). Furthermore, the cluster of Australian isolates CM1, CM2, CM4, CM5, and CM6 were all recovered from patients attending the same hospital in Melbourne, Australia, between 1991 and 1992. The English isolates CD75098 and CD75043 came from different patients attending the same hospital in Leeds in 1973 and 1975, respectively. Other examples are also evident in Fig. 1. These findings suggest that, in some cases, strains of C. dubliniensis may establish themselves in individual hospitals or patient populations and diversify through microevolution.

ITS sequencing, genotype-specific PCR, and genotype analysis using karyotype profiling.

The Cd25 DNA fingerprinting data obtained in this study confirm the findings of Joly et al. (17) that there are distinct subpopulations present within the species C. dubliniensis. In addition, when an SAB threshold of 0.60 was used to identify subgroups, the group I isolates remained as a single group, but the group II isolates separated into three distinct subgroups or clades. This suggests that there are significant differences in the genomic organization of these subpopulations. In order to investigate if these differences are also manifested at the level of nucleotide sequence, the ITS regions of seven representative Cd25 group I isolates and 12 Cd25 group II isolates were compared.

Four genotypes were identified among the isolates based on sequence differences; the seven Cd25 group I isolates sequenced were genotype 1, six Cd25 group II isolates sequenced were genotype 2, five Cd25 group II isolates sequenced were genotype 3, and one Cd25 group II isolate sequenced was genotype 4. Sequence variations in the isolates belonging to the four different genotypes were distributed between the ITS1 and ITS2 regions, while the 5.8S rDNA regions were identical (Fig. 2a). These differences correlated exactly with the clusters identified in the dendrogram generated from SAB values obtained from Cd25 fingerprinting. Genotype 1 and genotype 2 isolates separate from each other at an SAB node value of 0.19, and the five genotype 3 isolates and the single genotype 4 isolate separate from the genotype 2 isolates at an SAB node of 0.3. The genotype 4 isolate separates from, the genotype 3 isolates at an SAB node of 0.32.