Abstract

Background

Dengue is a disease which is now endemic in more than 100 countries of Africa, America, Asia and the Western Pacific. It is transmitted to the man by mosquitoes (Aedes) and exists in two forms: Dengue Fever and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. The disease can be contracted by one of the four different viruses. Moreover, immunity is acquired only to the serotype contracted and a contact with a second serotype becomes more dangerous.

Methods

The present paper deals with a succession of two epidemics caused by two different viruses. The dynamics of the disease is studied by a compartmental model involving ordinary differential equations for the human and the mosquito populations.

Results

Stability of the equilibrium points is given and a simulation is carried out with different values of the parameters. The epidemic dynamics is discussed and illustration is given by figures for different values of the parameters.

Conclusion

The proposed model allows for better understanding of the disease dynamics. Environment and vaccination strategies are discussed especially in the case of the succession of two epidemics with two different viruses.

Background

With medical research achievements in terms of vaccination, antibiotics and improvement of life conditions from the second half of the 20th century, it was expected that infectious diseases were going to disappear. Consequently, in developed countries the efforts have been concentrated on illnesses as cancer. However, at the dawn of the new century, infectious diseases are still causing suffering and mortality in developing countries. Malaria, yellow fever, AIDS, Ebola and other names will have marked the memory of humanity forever.

Among these diseases, dengue fever, especially known in Southeast Asia, is sweeping the world, hitting countries with tropical and warm climates. It is transmitted to the man by the mosquito of the genus Aedes and exists in two forms: the Dengue Fever (DF) or classic dengue and the Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF) which may evolve toward a severe form known as Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS). The major problem with dengue is the fact that the disease is caused by four distinct serotypes known as DEN1, DEN2, DEN3 and DEN4. A person infected by one of the four serotypes will never be infected again by the same serotype (homologus immunity), but he looses immunity to the three other serotypes (heterologus immunity) in about 12 weeks and then becomes more susceptible to developing dengue haemorrhagic fever.

The first form (DF) is characterized by a sudden fever without respiratory symptoms, accompanied by intense headaches making its nickname "breakbone fever" well deserved. It lasts between three and seven days but it stays benign. The haemorrhagic form (DHF) is also characterized by a sudden fever, nausea, vomiting and fainting due to low blood pressure caused by fluid leakage. It usually lasts between two and three days and can lead to death. The case of a second infection has therefore a capital importance because of the possibility of evolution toward the haemorrhagic form of the disease.

So far, the strategies of mosquito control by insecticides or similar techniques proved to be inefficient. Moreover, the deterioration of the environment, the climatic changes, the unsanitary habitat, the poverty and the uncontrolled urbanization are as many favorable factors to the infectious illness propagation in general and dengue fever in particular. During the last decades the global prevalence of the dengue progressed dramatically. The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries of Africa and America. The Southeast of Asia and the Western Pacific are seriously affected by the illness.

Before 1970, only nine countries had known epidemics of dengue haemorrhagic fever, but this number had increased more than fourfold in 1995 and about 2500 million of people are now exposed to the risk of the dengue fever. According to the present evaluations of the World Health Organization (WHO), about 50 million cases of dengue occur in the world every year, with an increasing tendency. In 1998, there were more than 616, 000 cases of dengue in America, of which 11, 000 cases of dengue haemorrhagic fever, that's twice the number of cases recorded in the same region during the year 1995. In 2001 there were 400, 000 cases of haemorrhagic fever in Southeast Asia, whereas, in Rio de Janeiro alone, 500, 000 people were struck by a dengue outbreak in 2002. The epidemic effect reached Florida and southern Texas [1-3].

During epidemics of the dengue fever the rate of the infectious among the susceptibles is often between 40 and 50 % but it may reach 80–90 % in favorable geographic and environmental conditions. Every year more then 500, 000 cases of dengue haemorrhagic require an hospitalization.

By contrast to malaria, caused by a parasite mainly in rural areas and transmitted by mosquito bites only at night, dengue is a viral disease resulting from the interaction of susceptible individuals with any of the four serotypes, mosquitoes of genus Aedes. The two recognized species of the vector transmetting dengue are Aedes aegypti and aedes albopictus. The first is highly anthropophilic, thriving in crowded cities and biting primarily during the day while the later is less anthropophilic and inhabits rural areas. Consequently, the importance of dengue is twofold: (i) Even in the absence of fatal forms, and because of its wide spreading and its multiple serotypes, the disease breeds significant economic and social costs (absenteeism, immobilization debilitation, medication). (ii) The potential risk of evolution towards the haemorrhagic form and the dengue shock syndrome with high economic costs and which may lead to death.

Mathematical modelling became an interesting tool for the understanding of these illnesses and for the proposition of strategies. The formulation of the model and the possibility of a simulation with parameter estimation, allow tests for sensitivity and comparison of conjunctures [4].

In the case of dengue fever, the mathematical models we have found in the literature propose compartmental dynamics with Susceptible, Exposed, Infective and Removed (immunised). In particular, SEIRS models [5] and SIR models [6] with only one virus or two viruses acting simultaneously [7] were considered.

In the present paper, while pointing out that the idea of two viruses coexisting in the same epidemic is controversial [7], a model with two different viruses acting at separated intervals of time is proposed. Our main purpose is to study the dynamics of dengue fever, while concentrating on its progression to the haemorrhagic form, in order to understand the epidemic phenomenon and to suggest strategies for the control of the disease. In search of clarity and simplicity, we assume that the latent period is not crucial for the susceptible-infective interaction, hence we omit the compartment of exposed and consider a SIR model.

Formulation of the model and stability analysis

Parameters of the model

We suppose that we dispose of a human population (respectively of mosquito population) of size Nh (resp. Nv) formed of Susceptibles Sh, of Infective Ih and of Removed Rh (resp. Sv and Iv).

The model supposes a homogeneous mixing of human and mosquito population so that each bite has an equal probability of being taken from any particular human. While noting bs the average biting rate of susceptible vectors, phv the average transmission probability of an infectious human to a susceptible vector, the rate of exposure for vectors is given by: (phvIhbs)/Nh. It is admitted [6] that some infections increase the number of bites by the infected mosquitos in relation to the susceptible, therefore, we will assume that the rate of infected mosquito bites bi is greater than the one of the susceptible mosquitos bs.

Noting pvh the average transmission probability of an infectious vector to human and Iv the infectious vector number, the rate of exposure for humans is given by: (pvhIvbi)/Nh so:

• The adequate contact rate of human to vectors is given by: Chv = Phvbs

• The adequate contact rate of vectors to human is given by: Cvh = pvhbi.

The man life span is taken equal to 25 000 days (68.5 years), and the one of the vector is of 4 days. Other parameters values are given in the following section.

Basis parameters

Values of the parameters used in the model are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

definitions and values of basis parameters used in simulations [5]

| Name of the parameter | Notation | Base value |

| transmission probability of vector to human | phv | 0.75 |

| transmission probability of human to vector | pvh | 0.75 |

| Bites per susceptible mosquito per day | bs | 0.5 |

| Bites per infectious mosquito per day | bi | 1.0 |

| Effective contact rate, human to vector | Chv | 0.375 |

| Effective contact rate, vector to human | Cvh | 0.75 |

| Human life span | 25000 days | |

| Vector life span | 4 days | |

| Host infection duration | 3 days |

Equations of the model

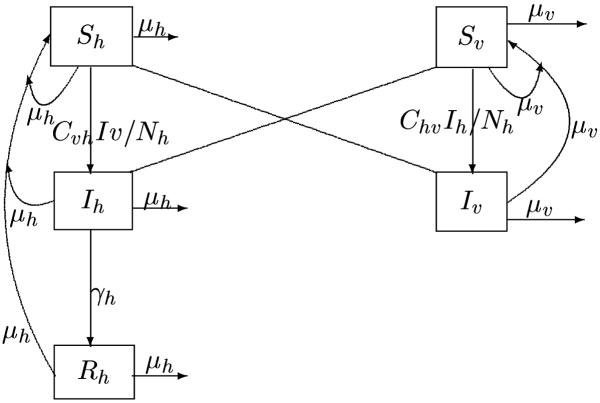

A schematic representation of the model is shown in Figure 1. We consider a compartmental model that is to say that every population is divided into classes, and that one individual of a population passes from one class to another with a suitable rate.

Figure 1.

schematic diagram: compartments of human and vector populations

Up to now there is no vaccine against dengue viruses but research is going on and the eventuality of an immunization program is not excluded in the medium term. In this study we investigate the effect of such an immunization option and we also discuss the possibility of a partial vaccination against each serotype that will enable the control of the second epidemic and the evolution of dengue to dengue haemorrhagic fever.

In the case of first epidemic, the simplest assumption is that a random fraction, p, of susceptible humans can permanently be immunized against all the four serotypes. While for the second epidemic, a partial immunization is applied to the removed from the first epidemic. The dynamics of this disease in the host and vector populations is given by the following equations:

First epidemic

The model is governed by the following equations:

Human population

Vector population

With the conditions Sh + Ih + Rh = Nh and Sv + Iv = Nv, so:

Rh = Nh - Sh - Ih and Sv = Nv - Iv

then the two previous systems become:

Equilibrium points

Let the set Ω given by:

Ω = {(Sh,Ih,Iv)/0 ≤ Iv ≤ Nv; 0 ≤ Ih; 0 ≤ Sh, (1 + p/μh)Sh + Ih ≤ Nh}

then we have the following theorem:

Theorem 1

The previous system admits two equilibrium points E1(Nh/(1 + p/μh), 0, 0) and E2 ( ,

, ,

, ) where

) where  ,

,  and

and

Proof:

see appendix A.1

Remark 1

Letting  , we can notice that:

, we can notice that:

• if R - 1 ≤ p' the trivial state E1 is the only equilibrium.

• if R - 1 >p' then the endemic equilibrium E2 will also be in Ω.

stability

Theorem 2

i) For R ≤ 1 + p' the state E1(Nh/(1 + p'), 0, 0) is globally asymptotically stable (ie  ).

).

ii) For R > 1 + p' the state E2 ( ,

, ,

, ) is locally asymptotically stable.

) is locally asymptotically stable.

Proof

see appendix A.2

Remark 2

The inequality R - 1 ≤ p' (ie μh(R - 1) ≤ p) represents the principle of herd immunity because the susceptible population may be protected from epidemics if enough people are immunized.

Second epidemic

In the same way as in the previous section we suppose the onset of a second epidemic with another virus. But in this case, we may assume that a proportion of the population of susceptibles is globally immunized against the four serotypes or partially immunized against one, two or tree viruses. Consequently, we may concentrate only on the removed from the first epidemic who are exposed to the DHF by taking the new population  . Therefore the model is given by the following equations:

. Therefore the model is given by the following equations:

Human population

Vector population

With the conditions  and Sv + Iv = Nv so:

and Sv + Iv = Nv so:

et Sv = Nv - Iv then the two previous systems become:

et Sv = Nv - Iv then the two previous systems become:

Equilibrium points

Let the set Ω given by:

with p' = p/μh

with p' = p/μh

Theorem 3

The previous system admits two equilibrium points: E1( /(1 + p'), 0, 0) and E2(

/(1 + p'), 0, 0) and E2( ,

,  ,

,  ) with

) with  ,

,  ,

,  and

and

Remark 1

We have two equilibrium points: the first E1 = ( /(1 + p'), 0, 0) is trivial, corresponding to to the state where the whole population is and will remain healthy. The second point is: E2 = (

/(1 + p'), 0, 0) is trivial, corresponding to to the state where the whole population is and will remain healthy. The second point is: E2 = ( ,

,  ,

,  ) it corresponds to the endemic state in which the disease persists in the two populations.

) it corresponds to the endemic state in which the disease persists in the two populations.

stability

Theorem 4

i) For R1 ≤ 1 + p' the state E1( , 0, 0) is globally asymptotically stable

, 0, 0) is globally asymptotically stable

ii) For R1 > 1 + p' the state E2 ( ,

,  ,

,  ) is locally asymptotically stable.

) is locally asymptotically stable.

Results and Discussion

Assuming a vaccination program as an option that would enable a proportion p of susceptible humans to be globally immunized against the four serotypes, the stability analysis shows that the population may be protected from epidemics if p satisfies the principle of herd immunity: μh(R - 1) ≤ p, where R is a function of the model parameters, defined as the number of new infected by an infective in interaction with susceptibles. Otherwise, there will be an endemic equilibrium and the disease will persist. But the problem is precisely in finding a vaccine against the four serotypes, which makes a strategy based on global immunization irrealistic in the short term. Meanwhile, a search leading to a partial vaccine against each serotype should be more feasible. In this direction, the proposed model shows that the evolution of dengue to dengue haemorrhagic fever can be controlled by a partial vaccine restricted to the people affected by the first epidemic.

In order to illustrate the dynamics of each epidemic and to study different strategies, a simulation was carried out using MATLAB routines with different values of the parameters implied in each model.

Mainly two directions can be envisaged to control the disease. The first may act on the number of mosquitoes and the second may consider the number of susceptible humans.

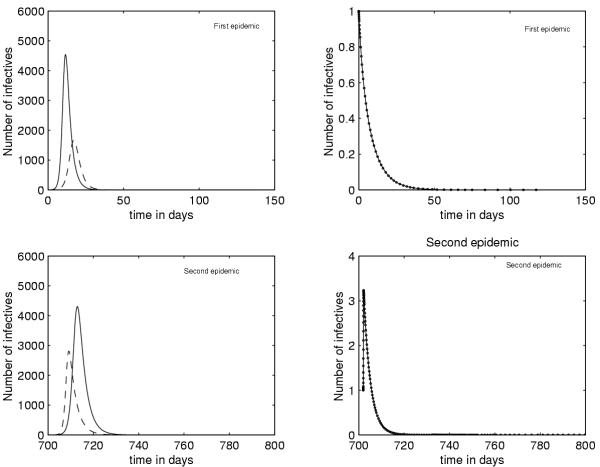

Figure 2 shows the effect of the reduction of the number of susceptibles with different values of the mosquito population Nv in the absence of vaccination (p = 0).

Figure 2.

the role of reduction of susceptible humans (Sh) and mosquito population (Nv) to control the disease in the first and second epidemic (model without vaccination (ie p = 0)) Sh = 10000, Nv = 50000 Sh = 2000, Nv = 5000 Sh = 5000, Nv = 50000

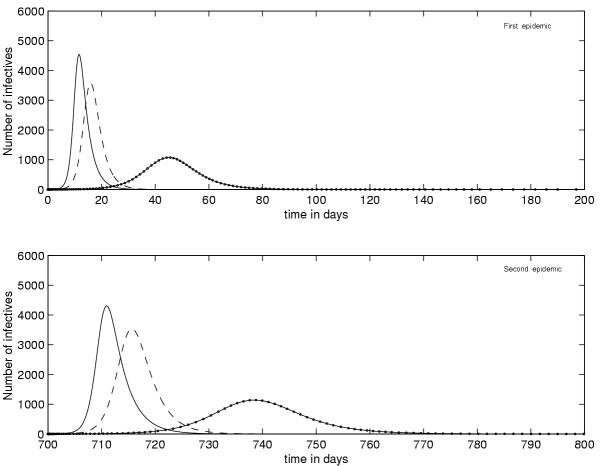

Figure 3 shows that in absence of vaccination (p = 0), a reduction of the mosquito population Nv is not sufficient to prevent the epidemic, it can only delay it's occurrence.

Figure 3.

the reduction of the mosquito population is not sufficient to eradicate dengue fever (model without vaccination (ie p = 0)) Nv = 50000 Nv = 30000 Nv = 800

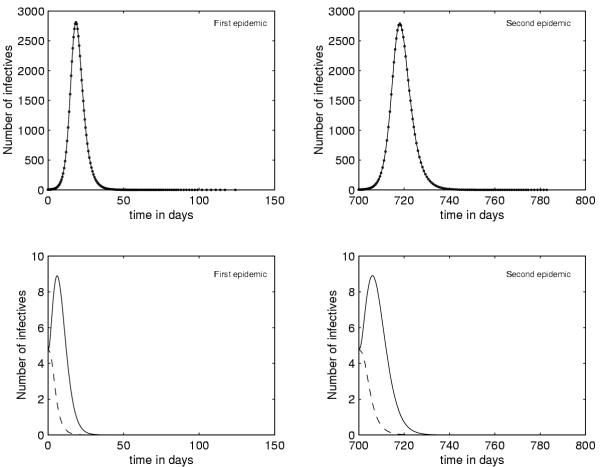

Figure 4 illustrates the benefit of vaccination in the control of the epidemic, a comparison is given for different values of the proportion p (p = 0, 0.25, 0.75), but this eventuality remains subject to the advent of the vaccine.

Figure 4.

The role of vaccination in the eradication of the disease in the first and second epidemic without vaccination (ie p = 0) p = 0.25 p = 0.75

Conclusion

As mentioned in the introduction, Our main purpose was to study the dynamics of dengue fever and its progression to the dengue haemorrhagic fever in order to understand the epidemic phenomenon and to suggest strategies for the control of the disease in general and the haemorrhagic form in particular. The nature of dengue epidemics is complex since it conjugates human, environmental, biological, geographical and socio-economic factors. Our model and simulations show that the strategy based on the prevention of dengue epidemic using vector control through environmental management (to eliminate the larval resting places such as containers like bottles, limp of canned foods, tire or other objects susceptible to keep water) or chemical methods (application of insecticides) remains insufficient since it only permits to delay the outbreak of the epidemic (figure 4). This conclusion agrees with the experiences realized by EA. Newton and P. Reiter using insecticides [5].

On the other hand, although the model suggests the reduction of susceptibles via vaccination, such a strategy is unlikely to be applicable in the short term because it faces some hurdles due to the fact that a vaccine must protect against the four serotypes at the same time. However, we consider this option since its eventuality is not excluded in the medium and long term.

In the short term, an intermediate solution would be to combine as much as possible, the environmental prevention and a partial vaccination essentially to avoid the haemorrhagic form of the disease caused by different viruses. This suggestion may help health-care policy makers to tackle environment causes as preventive measures and researchers to investigate and concentrate on the search for a vaccine against each serotype rather than looking for a vaccine against the four serotypes at the same time.

Appendix

proof of theorem 1

the equilibrium points satisfy the following relations:

From the equation (3) we have: ChvIh/Nv(Nv - Iv) - μvIv = 0

![]()

From the equation (1) we have: μhNh - (μh + p + CvhIv/Nh)Sh = 0 then

![]()

(because we have  ,

,  and

and  )

)

From the equation (2) we have:

![]()

On the other hand:

![]()

therefore it can be seen that values of Ih are:  = 0 or

= 0 or  substituting the equilibrium values of

substituting the equilibrium values of  in the equations (4) and (5) we obtain two equilibrium points:

in the equations (4) and (5) we obtain two equilibrium points:

i) the first E1 = (Nh/(1 + p'), 0, 0) is trivial in the sense that all individual are healthy and stay healthy for all time.

ii) The second point is: E2 = ( ,

,  ,

, ), (where

), (where  ,

,  and

and  ) that corresponds to the endemic state i.e the case where the disease persists in the two populations. ■

) that corresponds to the endemic state i.e the case where the disease persists in the two populations. ■

proof of theorem 2

i) For E1 the matrix of linearization (Jacobian matrix) is giving by:

Thus the eigenvalues of matrix  are:

are:

so E1 is stable for R < 1 + p'.

For the global stability, we consider the following Liapunov function:

![]()

thus:

![]()

So in Ω and for R ≤ 1 + p' we have:  ≤ 0.

≤ 0.

= 0

= 0

![]()

⇒ If R < 1 + p' then (Nh - (1 + p')Sh)Iv = 0, Ih = 0.

and If R = 1 + p' then (Nh - (1 + p')Sh)Iv = 0, IvIh = 0.

Thus the set {E1} is the largest invariant set within the set {(x, y, z)/ (x, y, z) = 0}. So according to the invariant set theorem: every trajectory in Ω tends to E1 as time t increases and as E1 is locally stable then it is globally asymptotically stable

(x, y, z) = 0}. So according to the invariant set theorem: every trajectory in Ω tends to E1 as time t increases and as E1 is locally stable then it is globally asymptotically stable

ii) the point E2

The local stability of E2 is governed by the matrix of linearization (Jacobian matrix) of E2 is given by:

Then the characteristic polynomial of  is given by:

is given by:

P(λ) = λ3 + Aλ2 + Bλ + C where:

![]()

and C = -det( ) thus:

) thus:

Or we have:

So: AB >C then following Routh-Hurwitz conditions for the polynomial P, the state E2 is locally asymptotically stable for R > 1 + p' ■

Authors' contributions

M.D contributed to Bibliography, the stability analysis, simulation and TEX writing

A.B proposed the models, contributed to discussion and writing

E.H.T contributed to bibliography, discussion of numerical results and English writing. All the authors read the final version before submission.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Royal Society of London under the DWSV scheme and the Moroccan C.N.R under the program PARS MI 23.

Contributor Information

M Derouich, Email: Derouich@sciences.univ-oujda.ac.ma.

A Boutayeb, Email: boutayeb@sciences.univ-oujda.ac.ma.

EH Twizell, Email: E.H.Twizell@brunel.ac.uk.

References

- Derouich M. Modélisation et Simulation de modèles avec et sans structure d'âge : Application au diabète et à la fièvre dengue. PhD thesis Faculty of Sciences, Oujda Morocco. 2001.

- Sesser S. Plague proportion. The Asian Wall Street Journal 2002. August 30 Septembre 1.

- Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever http://www.who.int/inf.fs/en/fact117.html

- Hethcote HW. The Mathematics of Infectious Diseases. SIAM review. 2000;42:599–653. [Google Scholar]

- Newton EA, Reiter P. A model of the transmission of dengue fever with an evaluation of the impact of ultra-low volume (ULV) Insecticide applications on dengue epidemics. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:709–720. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteva L, Vargas C. Analysis of a dengue disease transmission model. Mathematical Biosciences. 1998;150:131–151. doi: 10.1016/S0025-5564(98)10003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Hernàndez V. Competitive exclusion in a vector-host model for the dengue fever. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 1997;35:523–544. doi: 10.1007/s002850050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luenberger DG. Introduction to Dynamic systems, Models, and Applications. Theory, Models, and Applications, John Wiley & sons. 1997.

- Luenberger DG. Introduction to Applied Non linear systems and Chaos. S Wiggins, Springer. 1996.

- Dietz K. Transmission and control of arbovirus diseases. In: Ludwing D, editor. In Proceedings of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Epidemiology: Philadelphia. Philadelphia; 1974. pp. 104–106. [Google Scholar]