Abstract

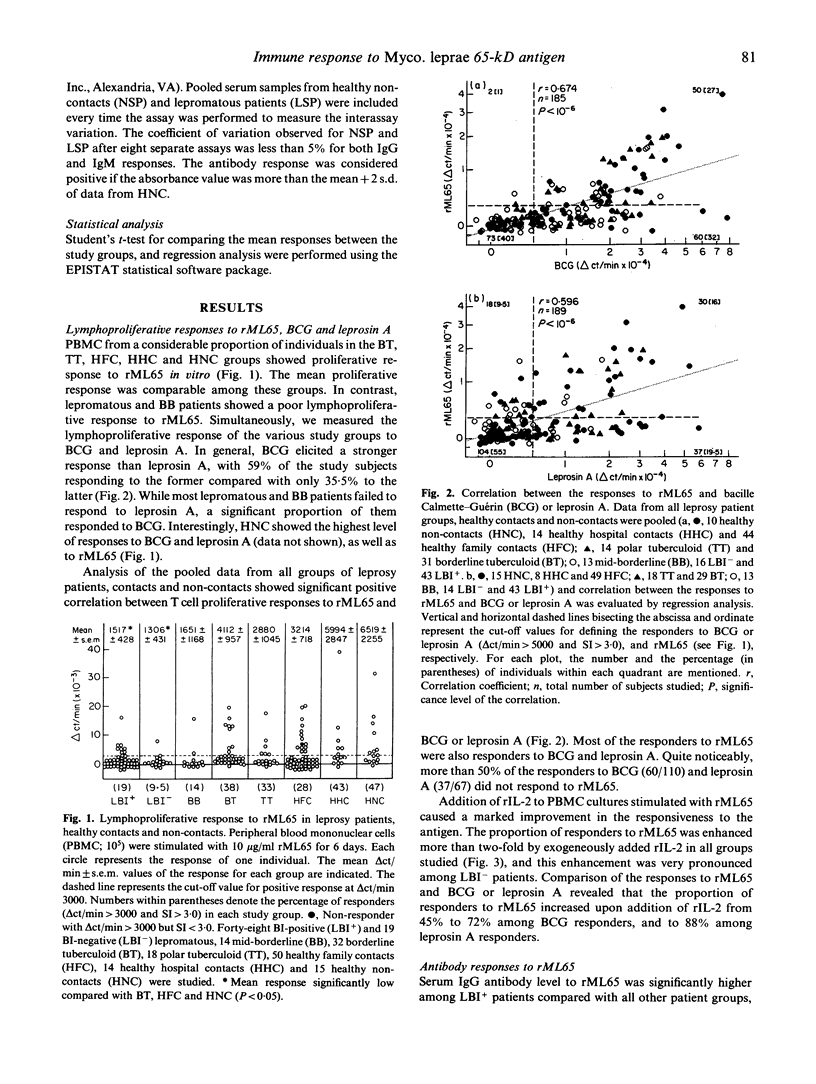

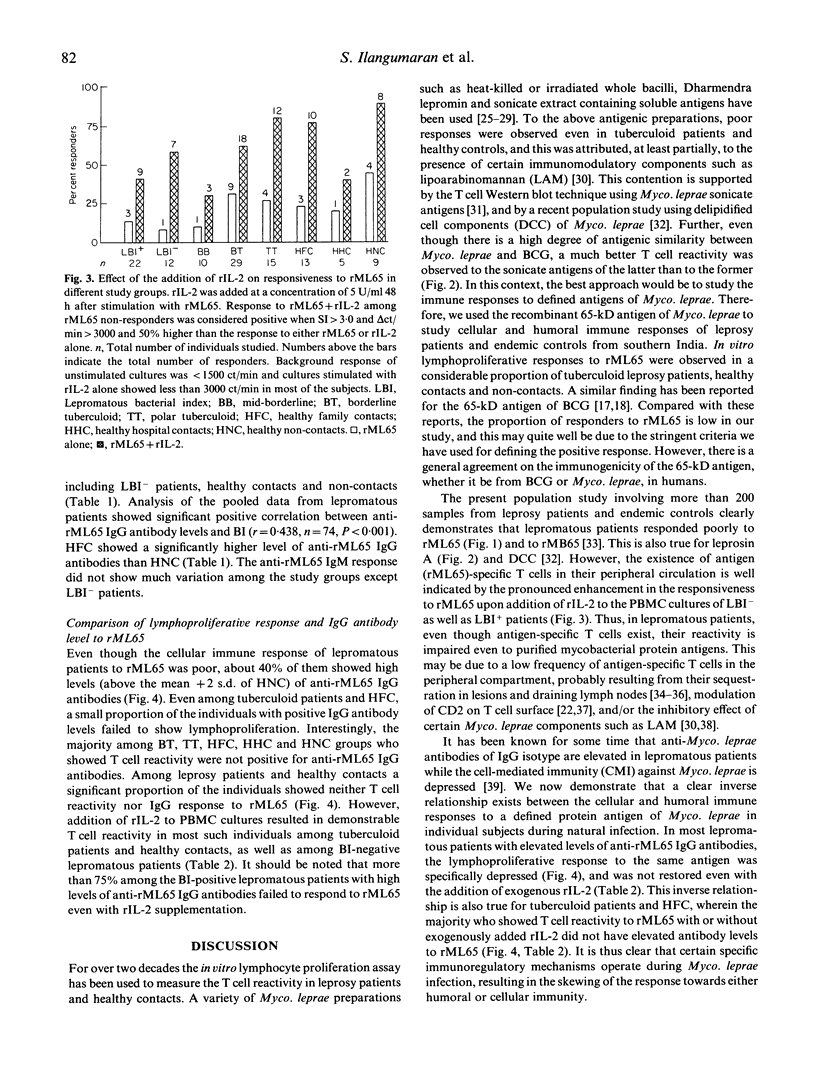

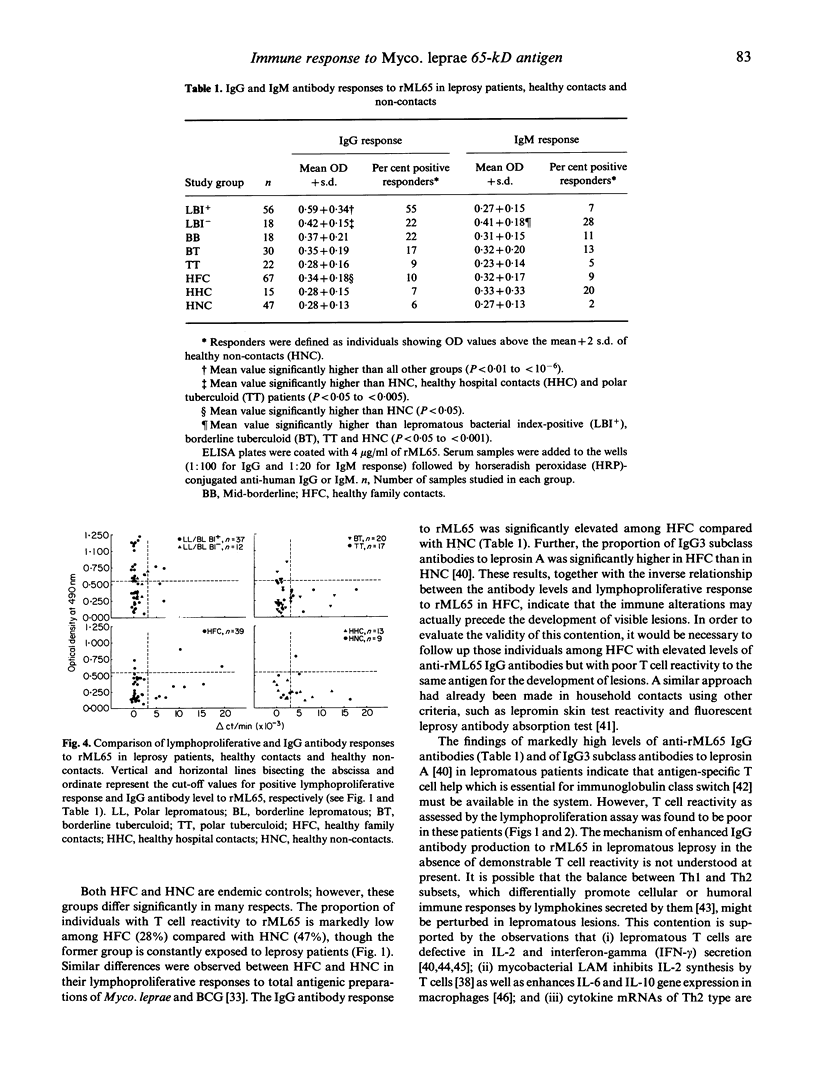

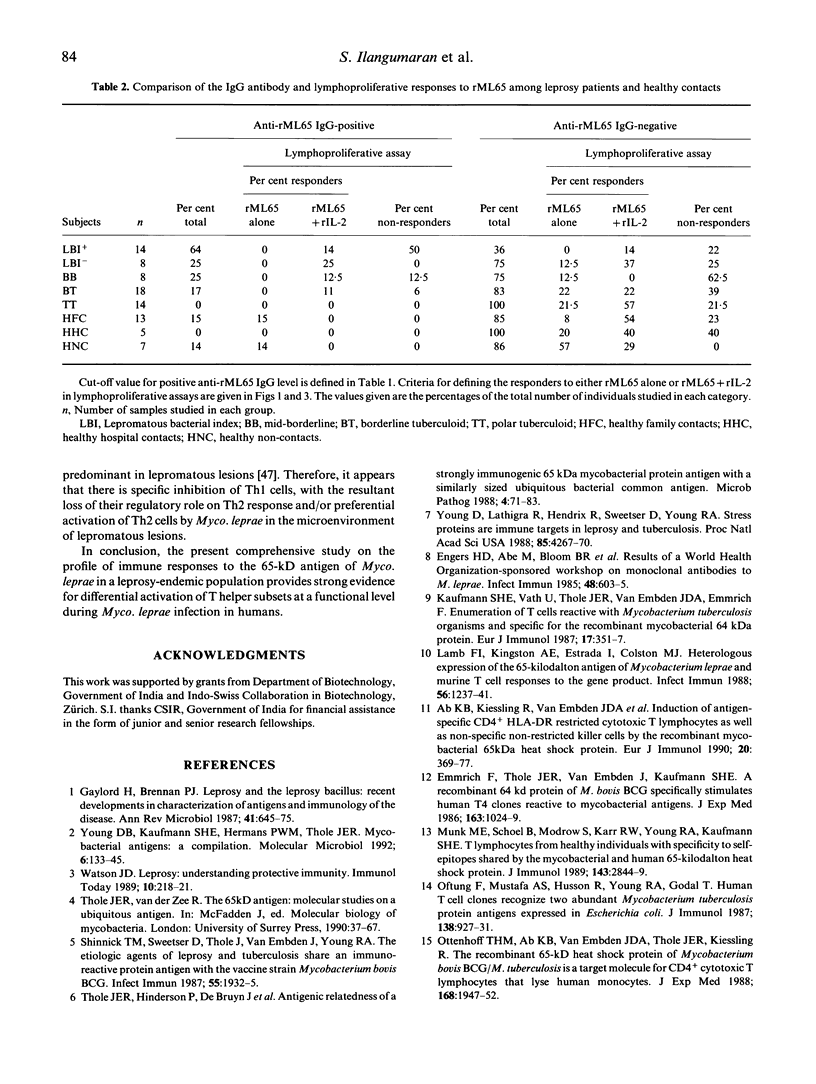

Cellular and humoral immune responses to recombinant 65-kD antigen of Mycobacterium leprae (rML65) were studied in leprosy patients and healthy contacts from a leprosy-endemic population. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a considerable proportion of tuberculoid leprosy patients, healthy contacts and non-contacts showed proliferative response to rML65 in vitro. A strong positive correlation was observed between the responses to rML65 and bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) or leprosin A. Addition of recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) enhanced the proportion of responders to rML65 considerably in all groups of leprosy patients, healthy contacts and non-contacts. Among lepromatous patients this enhancement was more pronounced in the bacterial index (BI)-negative group. These results indicate that the 65-kD antigen of Myco. leprae is a dominant T cell immunogen in our study population. Though lepromatous patients showed poor lymphoproliferative response to rML65, their IgG antibody levels to the same antigen were markedly high. Most of the BI-positive lepromatous patients with elevated anti-rML65 IgG levels did not show T cell reactivity even with the addition of rIL-2. On the other hand, tuberculoid leprosy patients, healthy contacts and non-contacts showed good T cell reactivity but low levels of IgG antibodies to rML65, thus indicating the presence of an inverse relationship between cell-mediated and humoral immune responses to a defined protein antigen of Myco. leprae in humans. A significant proportion of individuals among tuberculoid leprosy patients, healthy contacts and non-contacts showed neither T cell reactivity nor elevated levels of IgG antibody to rML65. However, in most of these subjects, a T cell response to rML65 was demonstrable with the addition of rIL-2. These results are discussed with reference to the immunoregulatory mechanisms occurring during Myco. leprae infection on the basis of differential activation of Th1 and Th2 subsets.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ab B. K., Kiessling R., Van Embden J. D., Thole J. E., Kumararatne D. S., Pisa P., Wondimu A., Ottenhoff T. H. Induction of antigen-specific CD4+ HLA-DR-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes as well as nonspecific nonrestricted killer cells by the recombinant mycobacterial 65-kDa heat-shock protein. Eur J Immunol. 1990 Feb;20(2):369–377. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams E., Garsia R. J., Hellqvist L., Holt P., Basten A. T cell reactivity to the purified mycobacterial antigens p65 and p70 in leprosy patients and their household contacts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990 May;80(2):206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb05235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M. A., Wallach D., Flageul B., Cottenot F. In vitro proliferative response to M. leprae and PPD of isolated T cell subsets from leprosy patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983 Apr;52(1):107–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. F., Chatterjee D., Abrams J. S., Lu S., Wang E., Yamamura M., Brennan P. J., Modlin R. L. Cytokine production induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan. Relationship to chemical structure. J Immunol. 1992 Jul 15;149(2):541–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj V. P., Katoch K. Detection of subclinical infection in leprosy: an 8 years follow-up study. Indian J Lepr. 1989 Oct;61(4):495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjune G. Variation of in vitro lymphocyte responses to M. leprae antigen in borderline tuberculoid leprosy patients. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1980 Mar;48(1):30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock W. E., Jr Perturbation of lymphocyte circulation in experimental murine leprosy. I. Description of the defect. J Immunol. 1976 Oct;117(4):1164–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chujor C. S., Kuhn B., Schwerer B., Bernheimer H., Levis W. R., Bevec D. Specific inhibition of mRNA accumulation for lymphokines in human T cell line Jurkat by mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan antigen. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992 Mar;87(3):398–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closs O., Reitan L. J., Negassi K., Harboe M., Belehu A. In vitro stimulation of lymphocytes in leprosy patients, healthy contacts of leprosy patients, and subjects not exposed to leprosy. Comparison of an antigen fraction prepared from Mycobacterium leprae and tuberculin-purified protein derivative. Scand J Immunol. 1982 Aug;16(2):103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S. D., Birdi T. J., Antia N. H. Presence of Mycobacterium leprae-reactive lymphocytes in lymph nodes of lepromatous leprosy patients. Scand J Immunol. 1988 Aug;28(2):211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1988.tb02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmrich F., Thole J., van Embden J., Kaufmann S. H. A recombinant 64 kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin specifically stimulates human T4 clones reactive to mycobacterial antigens. J Exp Med. 1986 Apr 1;163(4):1024–1029. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.4.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filley E., Abou-Zeid C., Waters M., Rook G. The use of antigen-bearing nitrocellulose particles derived from Western blots to study proliferative responses to 27 antigenic fractions from Mycobacterium leprae in patients and controls. Immunology. 1989 May;67(1):75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord H., Brennan P. J. Leprosy and the leprosy bacillus: recent developments in characterization of antigens and immunology of the disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:645–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.003241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill H. K., Mustafa A. S., Godal T. Vaccination of human volunteers with heat-killed M. leprae: local responses in relation to the interpretation of the lepromin reaction. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1988 Mar;56(1):36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godal T. Immunological aspects of leprosy--present status. Prog Allergy. 1978;25:211–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haregewoin A., Godal T., Mustafa A. S., Belehu A., Yemaneberhan T. T-cell conditioned media reverse T-cell unresponsiveness in lepromatous leprosy. Nature. 1983 May 26;303(5915):342–344. doi: 10.1038/303342a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G., Gandhi R. R., Weinstein D. E., Levis W. R., Patarroyo M. E., Brennan P. J., Cohn Z. A. Mycobacterium leprae antigen-induced suppression of T cell proliferation in vitro. J Immunol. 1987 May 1;138(9):3028–3034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Väth U., Thole J. E., Van Embden J. D., Emmrich F. Enumeration of T cells reactive with Mycobacterium tuberculosis organisms and specific for the recombinant mycobacterial 64-kDa protein. Eur J Immunol. 1987 Mar;17(3):351–357. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. B., Deshpande R. G., Davidson S. K., Navalkar R. G. Sero-immunoreactivity of cloned protein antigens of Mycobacterium leprae. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1992 Jun;60(2):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthäuer U., Graf D., Mages H. W., Brière F., Padayachee M., Malcolm S., Ugazio A. G., Notarangelo L. D., Levinsky R. J., Kroczek R. A. Defective expression of T-cell CD40 ligand causes X-linked immunodeficiency with hyper-IgM. Nature. 1993 Feb 11;361(6412):539–541. doi: 10.1038/361539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb F. I., Kingston A. E., Estrada I., Colston M. J. Heterologous expression of the 65-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium leprae and murine T-cell responses to the gene product. Infect Immun. 1988 May;56(5):1237–1241. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1237-1241.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis W. R., Meeker H. C., Schuller-Levis G. B., Gillis T. P., Marino L. J., Jr, Zabriskie J. Serodiagnosis of leprosy: relationships between antibodies to Mycobacterium leprae phenolic glycolipid I and protein antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Dec;24(6):917–921. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.6.917-921.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker H. C., Williams D. L., Anderson D. C., Gillis T. P., Schuller-Levis G., Levis W. R. Analysis of human antibody epitopes on the 65-kilodalton protein of Mycobacterium leprae by using synthetic peptides. Infect Immun. 1989 Dec;57(12):3689–3694. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.12.3689-3694.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehra V., Mason L. H., Fields J. P., Bloom B. R. Lepromin-induced suppressor cells in patients with leprosy. J Immunol. 1979 Oct;123(4):1813–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. R., Coffman R. L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk M. E., Schoel B., Modrow S., Karr R. W., Young R. A., Kaufmann S. H. T lymphocytes from healthy individuals with specificity to self-epitopes shared by the mycobacterial and human 65-kilodalton heat shock protein. J Immunol. 1989 Nov 1;143(9):2844–2849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukkaruppan V., Chakkalath H. R., James M. M. Immunologic unresponsiveness in leprosy is mediated by modulation of E-receptor. Immunol Lett. 1987 Jul;15(3):199–204. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(87)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira N., Kaplan G., Levy E., Sarno E. N., Kushner P., Granelli-Piperno A., Vieira L., Colomer Gould V., Levis W., Steinman R. Defective gamma interferon production in leprosy. Reversal with antigen and interleukin 2. J Exp Med. 1983 Dec 1;158(6):2165–2170. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oftung F., Mustafa A. S., Husson R., Young R. A., Godal T. Human T cell clones recognize two abundant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein antigens expressed in Escherichia coli. J Immunol. 1987 Feb 1;138(3):927–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenhoff T. H., Ab B. K., Van Embden J. D., Thole J. E., Kiessling R. The recombinant 65-kD heat shock protein of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin/M. tuberculosis is a target molecule for CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes that lyse human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1988 Nov 1;168(5):1947–1952. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Results of a World Health Organization-sponsored workshop on monoclonal antibodies to Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1985 May;48(2):603–605. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.603-605.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley D. S., Jopling W. H. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966 Jul-Sep;34(3):255–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche P. W., Theuvenet W. J., Britton W. J. Cellular immune responses to mycobacterial heat shock proteins in Nepali leprosy patients and controls. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1992 Mar;60(1):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook G. A., Carswell J. W., Stanford J. L. Preliminary evidence for the trapping of antigen-specific lymphocytes in the lymphoid tissue of 'anergic' tuberculosis patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1976 Oct;26(1):129–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheela R., Ilangumaran S., Muthukkaruppan V. R. Flow cytometric analysis of CD2 modulation on human peripheral blood T lymphocytes by Dharmendra preparation of Mycobacterium leprae. Scand J Immunol. 1991 Feb;33(2):203–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinnick T. M., Sweetser D., Thole J., van Embden J., Young R. A. The etiologic agents of leprosy and tuberculosis share an immunoreactive protein antigen with the vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1987 Aug;55(8):1932–1935. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1932-1935.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thole J. E., Hindersson P., de Bruyn J., Cremers F., van der Zee J., de Cock H., Tommassen J., van Eden W., van Embden J. D. Antigenic relatedness of a strongly immunogenic 65 kDA mycobacterial protein antigen with a similarly sized ubiquitous bacterial common antigen. Microb Pathog. 1988 Jan;4(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. D. Leprosy: understanding protective immunity. Immunol Today. 1989 Jul;10(7):218–221. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(89)90253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. D. Prospects for new generation vaccines for leprosy: progress, barriers, and future strategies. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1989 Dec;57(4):834–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura M., Uyemura K., Deans R. J., Weinberg K., Rea T. H., Bloom B. R., Modlin R. L. Defining protective responses to pathogens: cytokine profiles in leprosy lesions. Science. 1991 Oct 11;254(5029):277–279. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5029.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D. B., Kaufmann S. H., Hermans P. W., Thole J. E. Mycobacterial protein antigens: a compilation. Mol Microbiol. 1992 Jan;6(2):133–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D., Lathigra R., Hendrix R., Sweetser D., Young R. A. Stress proteins are immune targets in leprosy and tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jun;85(12):4267–4270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]