Abstract

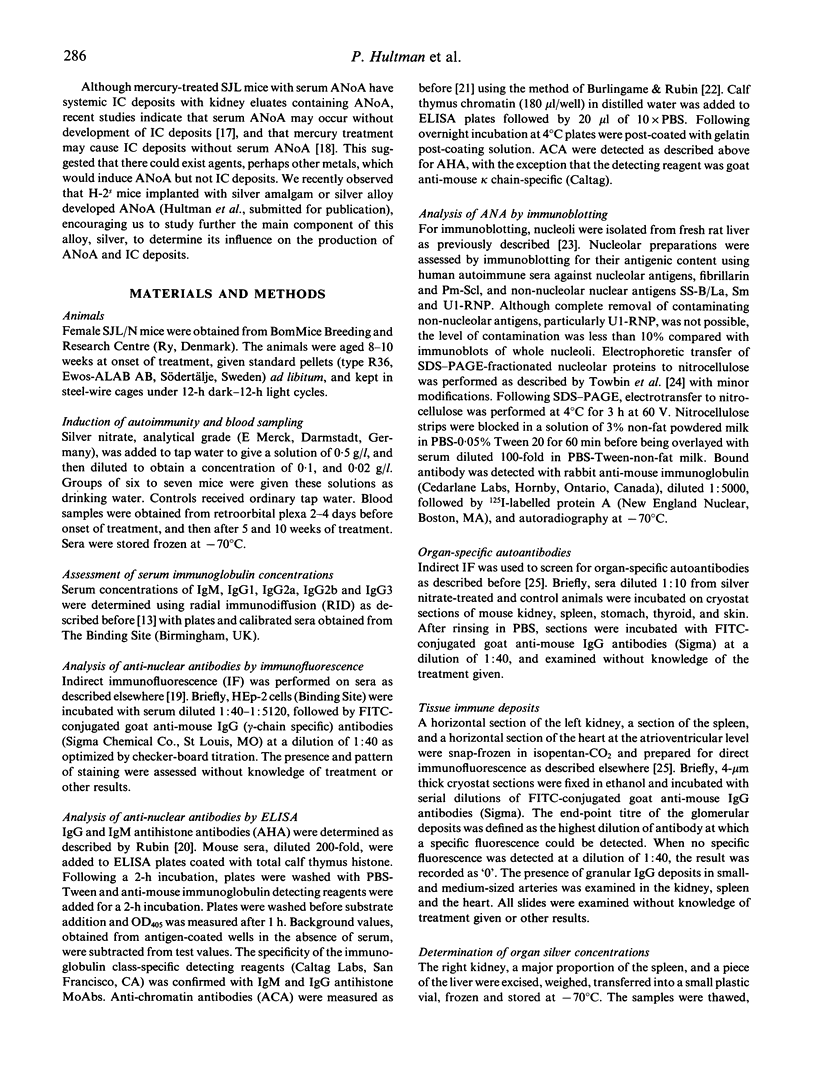

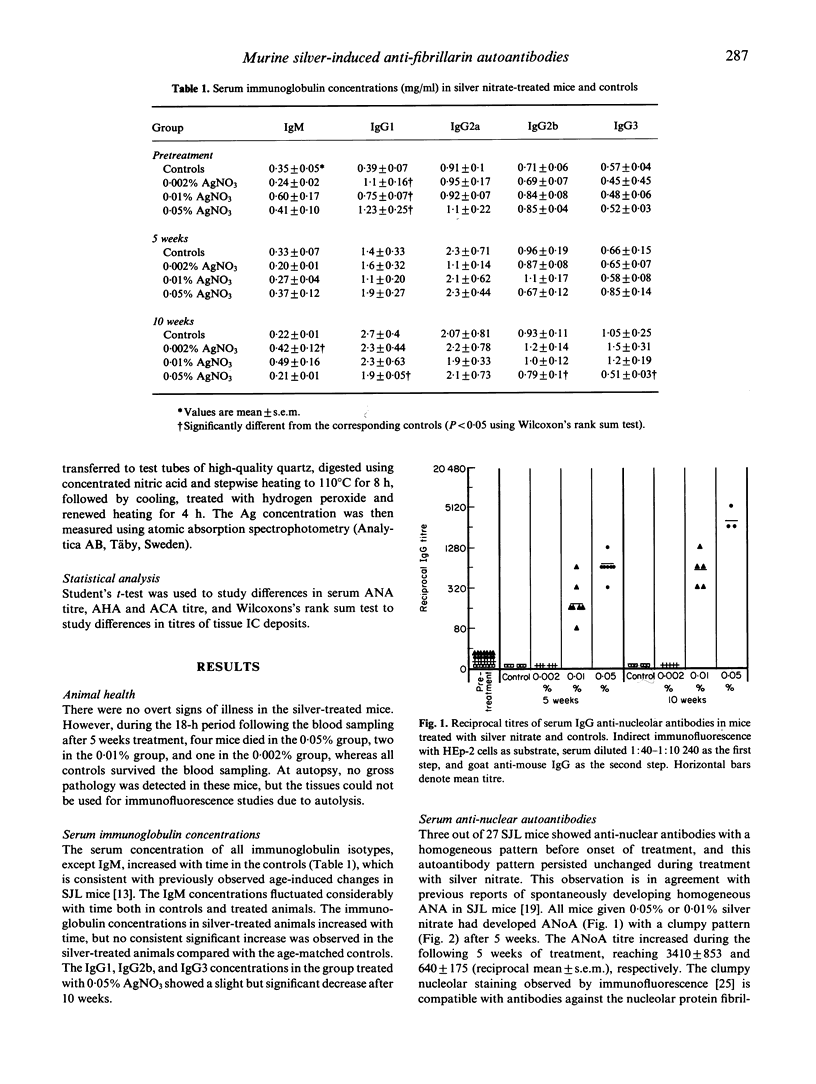

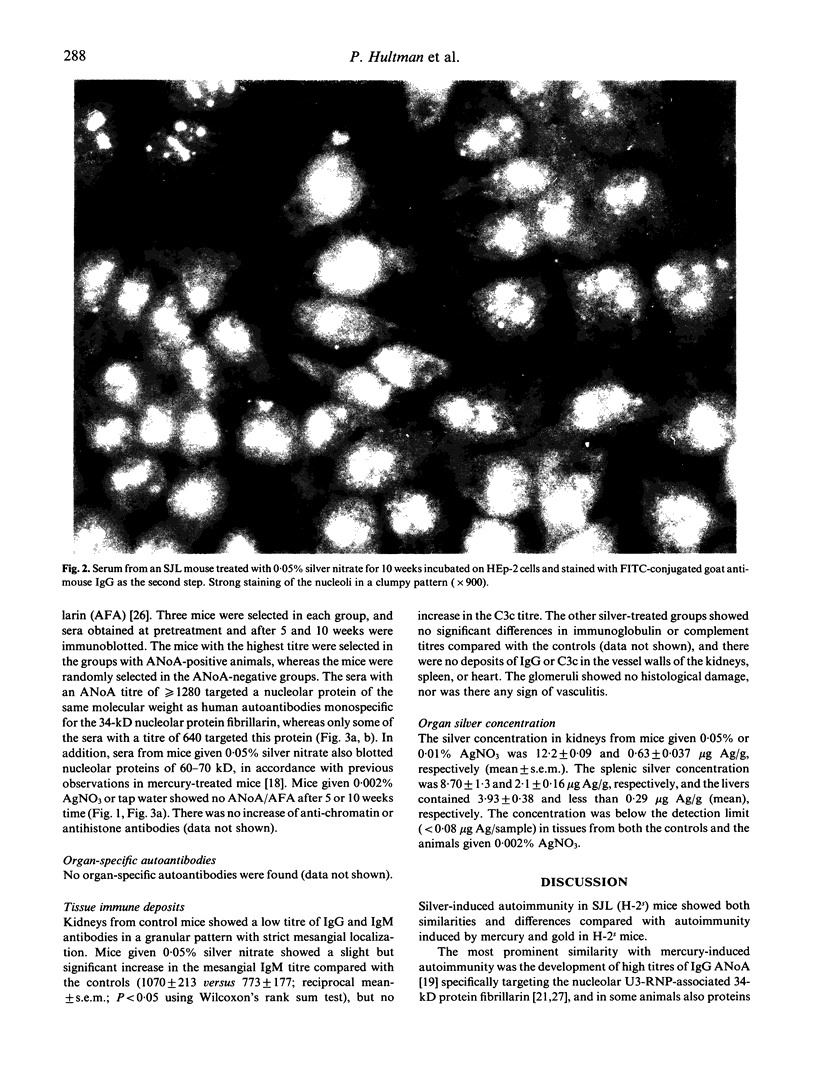

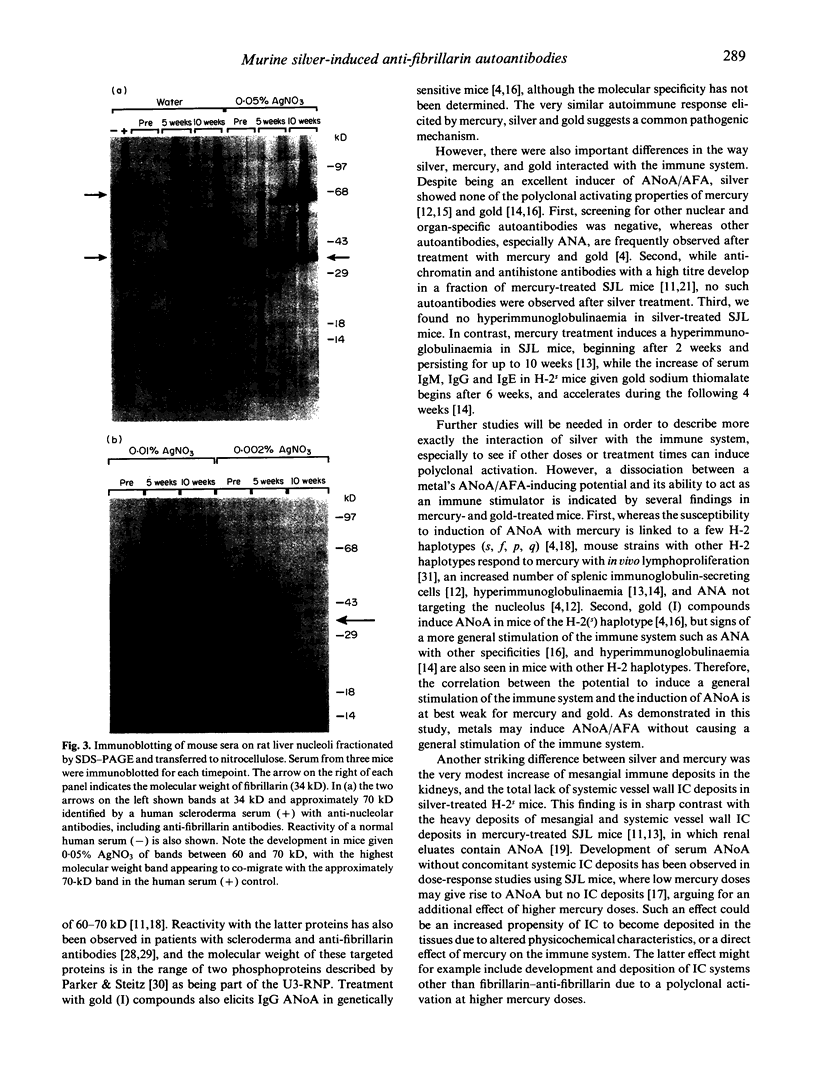

Female SJL (H-2s) mice developed serum IgG anti-nucleolar antibodies (ANoA) after 5 weeks treatment with 0.05% or 0.01% silver nitrate (AgNO3) in drinking water. Five more weeks of treatment increased the ANoA titre to 3410 +/- 853 and 640 +/- 175 (reciprocal mean +/- s.e.m.), respectively. Controls receiving ordinary tap water and mice given 0.002% AgNO3 showed no antinucleolar antibodies. The high-titre ANoA targeted a 34-kD nucleolar protein identified as fibrillarin, the major autoantigen in murine mercury-induced autoimmunity and in a fraction of patients with systemic scleroderma. Serum autoantibodies to chromatin or histones, kidney, spleen, stomach, thyroid, or skin antigens (except the nucleolus) were not found in any of the mice. There was no consistent significant increase of serum IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG3 concentrations after AgNO3 treatment compared with controls. Mice treated with 0.05% AgNO3 for 10 weeks showed a slight decrease in serum IgG1, IgG2b and IgG3 concentrations. These mice also showed a small but statistically significant increase in renal, mesangial IgM deposits, which was not accompanied by any increase in C3c deposits, whereas mice given lower doses of silver nitrate showed no significant increase in mesangial immunoglobulin immune deposits. Systemic vessel wall immune deposits were not found in any of the mice. In mice given 0.05% silver nitrate, the kidney showed the highest concentration of silver (12.2 +/- 0.09 micrograms Ag/g wet weight; mean +/- s.e.m.), followed by the spleen (8.7 +/- 1.3), and the liver (3.9 +/- 0.4). Treatment with 0.01% silver nitrate caused a different distribution of silver, with the highest concentration in the spleen (2.1 +/- 0.16 micrograms Ag/g), followed by the kidney (0.63 +/- 0.037), and the liver (< 0.29 micrograms Ag/g; mean). Silver seems to be a more specific inducer of antinucleolar/anti-fibrillarin autoantibodies than mercury and gold, lacks the general immune stimulating potential of mercury, and has only a weak tendency to induce renal immune deposits. These observations suggest that the autoimmune sequelae induced in mice by metals is dependent, not only upon the genetic haplotype of the murine strain, but also on the metal under investigation.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barr R. D. The mercurial nephrotic syndrome. East Afr Med J. 1990 Jun;67(6):381–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein R. M., Steigerwald J. C., Tan E. M. Association of antinuclear and antinucleolar antibodies in progressive systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982 Apr;48(1):43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi P. E. Lessons from animal models: the scope of mercury-induced autoimmunity. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992 Nov;65(2):81–84. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90210-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel G., Potter V. R. Nuclei from rat liver: isolation method that combines purity with high yield. Science. 1966 Dec 30;154(3757):1662–1665. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3757.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame R. W., Rubin R. L. Subnucleosome structures as substrates in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Immunol Methods. 1990 Dec 5;134(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90380-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eneström S., Hultman P. Immune-mediated glomerulonephritis induced by mercuric chloride in mice. Experientia. 1984 Nov 15;40(11):1234–1240. doi: 10.1007/BF01946653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Bell L. J., Eneström S., Pollard K. M. Murine susceptibility to mercury. I. Autoantibody profiles and systemic immune deposits in inbred, congenic, and intra-H-2 recombinant strains. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1992 Nov;65(2):98–109. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Bell L. J., Eneström S., Pollard K. M. Murine susceptibility to mercury. II. autoantibody profiles and renal immune deposits in hybrid, backcross, and H-2d congenic mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993 Jul;68(1):9–20. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Eneström S. Dose-response studies in murine mercury-induced autoimmunity and immune-complex disease. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992 Apr;113(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Eneström S. Mercury induced B-cell activation and antinuclear antibodies in mice. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1989 Mar;28(3):143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Eneström S. Mercury induced antinuclear antibodies in mice: characterization and correlation with renal immune complex deposits. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988 Feb;71(2):269–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Eneström S., Pollard K. M., Tan E. M. Anti-fibrillarin autoantibodies in mercury-treated mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989 Dec;78(3):470–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Eneström S. The induction of immune complex deposits in mice by peroral and parenteral administration of mercuric chloride: strain dependent susceptibility. Clin Exp Immunol. 1987 Feb;67(2):283–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtenbach U., Gleichmann H., Nagata N., Gleichmann E. Immunity to D-penicillamine: genetic, cellular, and chemical requirements for induction of popliteal lymph node enlargement in the mouse. J Immunol. 1987 Jul 15;139(2):411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicka-Muranyi M., Behmer O., Uhrberg M., Klonowski H., Bister J., Gleichmann E. Murine systemic autoimmune disease induced by mercuric chloride (HgCl2): Hg-specific helper T-cells react to antigen stored in macrophages. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1993 Feb;15(2):151–161. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(93)90091-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockie L. M., Smith D. M. Forty-seven years experience with gold therapy in 1,019 rheumatoid arthritis patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985 May;14(4):238–246. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(85)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa M., Takahashi K., Otsuka F. Induction of anti-nuclear antibodies in mice orally exposed to cadmium at low concentrations. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988 Jul;73(1):98–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker K. A., Steitz J. A. Structural analysis of the human U3 ribonucleoprotein particle reveal a conserved sequence available for base pairing with pre-rRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Aug;7(8):2899–2913. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifle J., Anderer F. A., Franke M. Characterisation of nucleolar proteins as autoantigens using human autoimmune sera. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986 Dec;45(12):978–986. doi: 10.1136/ard.45.12.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch P., Vohr H. W., Degitz K., Gleichmann E. Immunological alterations inducible by mercury compounds. II. HgCl2 and gold sodium thiomalate enhance serum IgE and IgG concentrations in susceptible mouse strains. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1989;90(1):47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer G., Steen V. D., Penning C. A., Medsger T. A., Jr, Tan E. M. Correlates between autoantibodies to nucleolar antigens and clinical features in patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Arthritis Rheum. 1988 Apr;31(4):525–532. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter R., Tessars G., Vohr H. W., Gleichmann E., Lührmann R. Mercuric chloride induces autoantibodies against U3 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein in susceptible mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jan;86(1):237–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C. J., Balazs T., Egorov I. K. Mercuric chloride-, gold sodium thiomalate-, and D-penicillamine-induced antinuclear antibodies in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1986 Nov;86(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(86)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrallhammer-Benkler K., Ring J., Przybilla B., Meurer M., Landthaler M. Acute mercury intoxication with lichenoid drug eruption followed by mercury contact allergy and development of antinuclear antibodies. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992 Aug;72(4):294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann D., Kubicka-Muranyi M., Mirtschewa J., Günther J., Kind P., Gleichmann E. Adverse immune reactions to gold. I. Chronic treatment with an Au(I) drug sensitizes mouse T cells not to Au(I), but to Au(III) and induces autoantibody formation. J Immunol. 1990 Oct 1;145(7):2132–2139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller-Winkler R., Radaszkiewicz T., Gleichmann E. Immunopathological signs in mice treated with mercury compounds--I. Identification by the popliteal lymph node assay of responder and nonresponder strains. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1988;10(4):475–484. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(88)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]