Among the first major events during development of metazoans is the specification of the anteroposterior (head/tail or mouth/anus) and the dorsoventral (back-belly) embryonic axes. The genetic network controlling dorsoventral axis specification is best understood and remarkably, it is evolutionarily conserved from fruit flies to mammals. Labeling of single cells or small groups of cells and tracing them throughout development has revealed that fate specification in Xenopus and zebrafish depends on the position within the embryo during blastula and gastrula stages, in particular along the future dorsoventral axis. The positional information is furnished by an activity gradient of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) that promote ventral specification in a dose-dependent fashion. The key structure in the establishment of the ventral to dorsal BMP activity gradient in vertebrate embryos is the dorsal gastrula or Spemann–Mangold organizer at the future dorsal side of the embryo (1). Embryological extirpation experiments revealed that the formation of the gastrula organizer and consequently of dorsal structures is specified by maternally supplied determinants in frog and fish. In contrast, whereas the development of ventral fates in Xenopus is associated with maternally expressed BMP-encoding genes, in zebrafish the same set of proteins is exclusively expressed from the zygotic genome. This poses the question about the nature of the upstream regulatory mechanisms involved in zebrafish. In a recent issue of PNAS, a report by Sidi et al. (2) provided thrilling evidence that at least in the zebrafish embryo there may be no ventral default state at all. Sidi and collaborators identified a distinct TFG-β ligand Radar as a part of the maternal dowry that activates the zygotic expression of BMP genes and they start to delineate the pathway involved.

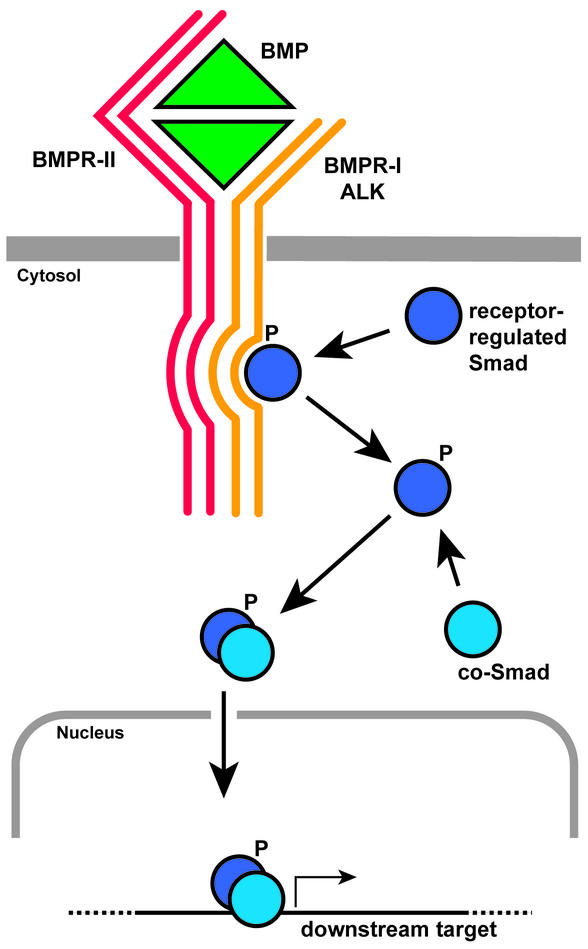

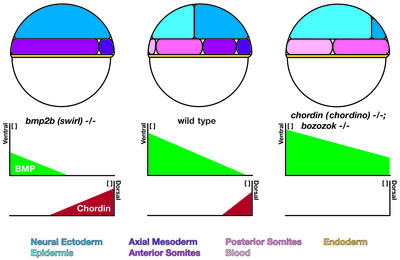

BMP2b, BMP4, and BMP7 have been implicated in dorsoventral axis formation in the zebrafish embryo and form a branch of the large superfamily of transforming growth factor type β proteins (TGF-β) (3, 4). Typically, BMP ligands bind to the homodimeric BMP type II receptor (BMPR-II) that subsequently recruits the homodimeric BMP type I receptor to form the active tetrameric receptor complex. The activated BMP-receptor complex phosphorylates a cytosolic protein of the receptor-regulated Smad family that oligomerizes with a co-Smad and subsequently enters the nucleus to activate gene transcription of downstream targets leading to ventral fate determination (Fig. 1). BMP antagonists act by binding to the BMP ligands and prevent the formation and activation of the BMP receptor complexes, thus promoting dorsal fate specification. Misexpression of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 ligands in Xenopus and zebrafish cause strong reduction of dorsal structures like notochord, brain, and pharynx, whereas ventral structures, including blood, posterior somites, and epidermis, are enlarged (Fig. 2). Similar reduction of dorsal structures is observed in zebrafish mutants in which BMP antagonists and negative regulators are inactivated (5, 6). Conversely, functional inactivation by means of induced mutations in the zebrafish genes bmp2b (swirl) and bmp7 (snailhouse) results in suppression of ventral fates and expansion of dorsal structures (7).

Figure 1.

BMP signaling pathway (see text for details).

Figure 2.

Fate specification in zebrafish embryos at the onset of gastrulation. In wild type, the BMP activity gradient is set up by the combination of positive autoregulation and negative regulation through BMP-antagonists like Chordin. In the absence of Chordin and Bozozok, the influence of BMP signaling expands dorsally, and ventral tissues such as posterior somitic mesoderm and blood are enlarged. Inactivation of bmp2b causes the opposite scenario; activity of BMP dramatically increases leading to the induction of excessive dorsal fates like neuroectoderm and anterior somitic mesoderm.

The first key step in shaping the ventral to dorsal BMP activity gradient occurs at blastula stages and depends on maternally provided dorsal determinants. Upon fertilization, dorsal determinants deposited at the vegetal pole of the egg are transported to the prospective dorsal blastomeres. The dorsal determinants promote transcriptional activation of the genes required to establish the blastula organizer, which is responsible for the formation of the Spemann–Mangold organizer at the future dorsal side of the gastrula. As a consequence of the translocation of the dorsal determinants, β-catenin, a downstream component of the Wnt-signaling pathway, accumulates more strongly in the nuclei in the dorsal region of frog and zebrafish blastulae. Down-regulation of β-catenin by antisense oligonucleotides in frog embryos, interference with its nuclear accumulation in the zebrafish ichabod (8) mutant, or mutational inactivation in the mouse causes dramatic increase in BMP activity and complete lack of dorsal structures. Conversely, ventral overexpression of β-catenin elicits secondary axis formation. In summary, there is a wealth of experimental data strongly arguing in favor of the maternal canonical Wnt pathway being the key player during dorsal fate specification. In Xenopus, one possible scenario includes the microtubule-dependent translocation of Dishevelled protein from vegetal to the future dorsal side of the embryo (9). As Dishevelled is a positive regulator of β-catenin, this would ultimately cause an asymmetric distribution of nuclear β-catenin accumulation along the dorsoventral axis. Dorsally acting β-catenin activates a gene cascade whose main function is to directly or indirectly eliminate dorsal expression of bmp genes expression in the blastula (10–14).

The somewhat late activation of the ventralizing BMP2/4/7 signaling pathway during zebrafish embryogenesis does not support the simplified assumption of a maternally regulated ventral default state within the early blastoderm. On the other hand, mutational and molecular analyses have revealed a maternal requirement of the TGF-β type I receptor Alk8 for the initiation of BMP2/4/7 signaling, as embryos from females homozygous for the mutant alk8 allele lost-a-fin or alk8-morphant embryos are strongly dorsalized (15, 16). Interestingly, bmp2b expression is significantly reduced in zebrafish gastrulae after RNA injection of dominant-negative alk8 constructs, whereas overexpression of constitutively active Alk8 causes increase in bmp2b, without influencing bmp4 expression (17). Furthermore, embryos derived from females homozygous for null mutations in the smad5 locus exhibit reduced levels of the initial bmp7 and bmp2b expression (18, 19). These observations already predicted the existence of a maternal signal, likely from TGF-β superfamily, inducing bmp gene expression in zebrafish.

The zebrafish gene radar represents a compelling candidate for the mysterious maternal activator of bmp gene expression. Initial work had revealed Radar possessed a strong ventralizing activity when overexpressed in the early embryo, comparable to effects seen after BMP2b and BMP4 misexpression (20), and a careful analysis of the expression profile showed that radar transcripts are already maternally contributed.

Earlier studies had shown that zygotic expression of radar occurring at the end of gastrulation may not be needed for dorsoventral axis formation, though a function in establishing the integrity of the zebrafish axial vasculature may involve dorsoventral patterning events as well (21). Mutational analysis of radar did not reveal any participation in early dorsoventral axis formation (20). To distinguish between the zygotic and maternal functions of Radar, Sidi et al. (2) have elegantly used an antisense RNA interference technology mediated by so called morpholino (MO)-oligonucleotides (22). One MO-oligonucleotide was targeted to inhibit translation of processed transcripts of both maternal and zygotic origin (23). Another MO-oligonucleotide was designed to interfere with processing of newly, zygotically synthesized, but not with maternally provided RNAs (24). Injecting zebrafish embryos with the latter MO-oligonucleotide recapitulates the phenotype observed in embryos carrying a genomic deletion encompassing the radar locus. That dorsoventral axis formation was not affected in these embryos is consistent with the notion that zygotic radar does not regulate axis specification (25). Strikingly, when former radar-MO was used, 50% of the embryos also exhibited excessive development of dorsal tissues. Three nonexclusive scenarios may explain why only a fraction of embryos was affected and to varying degrees. Injected MO-oligonucleotides compete for deposited maternal radar transcripts with the translation machinery. In addition, active Radar protein may already be present in the oocyte before fertilization. Functional redundancy with related factors that harbor ventralizing activity as well cannot be ruled out. However, another zebrafish GDF6 ortholog, dynamo (gdf6α), is not involved in early dorsoventral axis formation (26).

Given that active TGF-β molecules are thought to interact with the receptor complex as either homo- or heterodimers, overexpressing C-terminally truncated forms of Radar could act in a dominant-negative manner by forming heterodimers with endogenous ligands that are unable to signal. Overexpression of such dominant-negative Radar (RadarDN) in young embryos causes stronger dorsalization than observed in radar-MO-injected embryos, providing an independent support for the idea of maternal Radar being a key player in early axis specification.

How does Radar impact embryonic patterning? Induction of bmp2b and bmp4 gene expression at early blastula stages was found to be dramatically reduced in radar morphants, whereas expression of bmp7 was unchanged, leading to the conclusion that induction of bmp2b and bmp4 but not bmp7 requires Radar function. Remarkably, the onset and expression domain of the organizer-specific BMP antagonist chordin was not affected. Similarly, dorsal expression of bozozok, encoding a negative regulator of bmp2b gene expression, and a direct downstream target of β-catenin was also unchanged. Consistently, the functionally redundant ventralizing genes vox/vega1 and vent/vega2 in zebrafish, which are not dependent on BMP signaling at early stages, are not down-regulated in radar morphant embryos. These observations clearly demonstrate that maternally provided Radar is required to initiate zygotic gene expression of bmp2b and bmp4 specifically, and suggest that it does not interact with dorsal-specifying or BMP-independent genes. The observation of stronger dorsalization after overexpression of RadarDN versus MO-induced down-regulation of Radar function can be easily explained by the stronger suppression of bmp2b, bmp4 and especially of bmp7 gene expression at blastula and pregastrula stages. The expression domain of the BMP antagonist Chordin is expanded ventrolaterally, which by itself could explain the much stronger dorsalization capacity of overexpressed RadarDN. In contrast to the radar-MO oligonucleotides that cannot interfere with putative maternally deposited Radar protein, RadarDN may actually heterodimerize with maternally supplied wild-type Radar protein. Thus, overexpression of dominant negative Radar could reflect a complete removal of Radar function. However, the possibility of functional interference by RadarDN with related BMP/GDF proteins cannot be ruled out. Sidi and collaborators provide compelling evidence that induction of dorsal and ventral fates both seem to be controlled maternally and that very likely there are additional and possibly related factors in the zebrafish embryo that act to specify ventral fates.

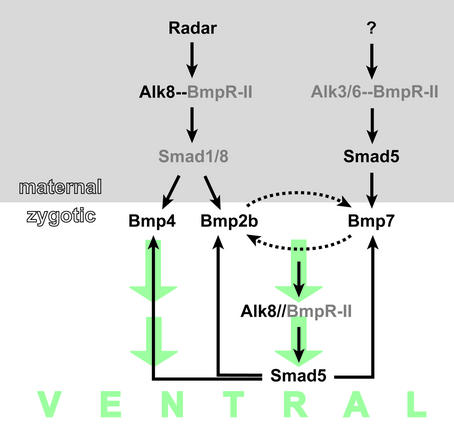

Epistatic analysis further supports the notion of radar acting upstream of bmp gene expression (3). Excess Radar function in early embryo was unable to rescue the mutant and morphant phenotypes of several BMP pathway components, including bmp2b, bmp7 and the TGF-β type I receptor alk8 (MO). Conversely, misexpression of bmp2b, bmp4, bmp7, and constitutively active alk8 all suppressed the radar-morphant phenotype, showing that maternal function of radar is crucial for initiation of the ventral character in the early zebrafish embryo. Maternal inactivation of smad5 or alk8, respectively, led to stronger dorsalization than inactivation of individual BMP ligands, reminiscent of embryos with impaired radar function. This raises the question of whether the TGF-β type I receptor and the intracellular messenger are also involved in Radar signaling. In addition, double alk8 and radar MO-injection studies have also indicated that alk8 and radar might cooperate in ventral specification. Whereas injections of subinhibitory alk8 and radar MO-concentrations when applied individually, typically produce only mildly dorsalized phenotypes, coinjection of MO-alk8 and MO-radar at the same doses caused significantly stronger dorsalization, with bmp2b and bmp4 expression eliminated. The synergistic interactions between Radar and the TGF-β type I receptor Alk8 suggest that maternal Radar signals through maternal Alk8 (Fig. 3). However, the dorsalization in maternal-zygotic alk8 mutant embryos is much stronger than in radar-morphant embryos. The next challenge is to determine whether additional ligands cooperate with Radar in activating Alk8, whether other type I receptors are also at work in induction of BMP gene expression, and which Smad factors are used in this pathway. Although the dominant negative mutant allele smad5 is epistatic to radar as well, several newly identified smad5 null alleles, have revealed that in contrast to Radar positively regulating bmp2b and bmp4 expression, maternal Smad5 rather acts on bmp7 (ref. 19; Fig. 3). It will be important to test whether overexpression of Radar can suppress the strongly dorsalized phenotype of maternal smad5 mutant embryos.

Figure 3.

Model of the maternal Radar signaling pathway mediating early steps of dorsoventral axis formation. Radar acts through the TGF-β type I receptor Alk8 and causes transcriptional activation of BMP2b and BMP4. The intracellular signal transducer, believed to be a member of the Smad1/5/8 protein family is not known (indicated in gray), although Smad5 may be excluded. Maternal Smad5 may transduce the signal of a hypothesized distinct maternal signaling pathway acting in parallel to Radar. Alk8 is also the receptor for zygotic BMP2b/7 signaling, and Smad5 transduces that signal, leading to the autoregulatory transcriptional activation of BMP2b/4/7.

In contrast to the situation in Xenopus, where BMP2/4/7 are provided maternally and may create a default state, the delayed zygotic initiation of ubiquitous bmp2b/4/7 expression in the zebrafish embryo could be interpreted as a ventral default setting of the prospective blastoderm in a similar way. Now with the report by Sidi et al. identifying a maternally contributed secreted factor upstream of BMP2b/4/7 expression, a revised picture of ventral fate specification in zebrafish is at hand.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 3315 in issue 6 of volume 100.

References

- 1.Spemann H, Mangold H. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45:13–38. (reprint of translated original paper from 1924). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidi S, Goutel C, Peyriéras N, Rosa F M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3315–3320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530115100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massagué J. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–178. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan B L. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1580–1594. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammerschmidt M, Pelegri F, Mullins M C, Kane D A, van Eden F J M, Granato M, Brand M, Furutani-Seiki M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C-P, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;123:95–102. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez E, Fekany-Lee K, Carmany-Rampey A, Erter C, Topczewski J, Solnica-Krezel L. Genes Dev. 2000;14:3087–3092. doi: 10.1101/gad.852400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullins M C, Hammerschmidt M, Kane D A, Odenthal J, Brand M, van Eden F J M, Furutani-Seiki M, Granato M, Haffter P, Heisenberg C-P, et al. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;123:81–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelly C, Chin A J, Leatherman J L, Kozlowski D J, Weinberg E S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:3899–3911. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller J R, Rowning B A, Larabell C A, Yang-Snyder J A, Bates R L, Moon R T. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:427–436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fekany-Lee K, Gonzalez E, Miller-Bertoglio V, Solnica-Krezel L. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:2333–2345. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudoh T, Dawid I B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7852–7857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141224098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan C-M, Sokol S Y. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:2581–2589. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13017–13022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glavic A, Gomez-Skarmeta J L, Mayor R. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:368–376. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mintzer K A, Lee M A, Runke G, Trout J, Whitman M, Mullins M C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:859–869. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer H, Lele Z, Rauch G J, Geisler R, Hammerschmidt M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:849–858. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payne T L, Postlethwait J H, Yelick P C. Mech Dev. 2001;100:275–289. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid B, Fürthauer M, Connors S A, Trout J, Thisse B, Thisse C, Mullins M C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2000;127:957–967. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer C, Mayr T, Nowak M, Schumacher J, Runke G, Bauer H, Wagner D S, Schmid B, Imai Y, Talbot W S, et al. Dev Biol. 2002;250:263–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goutel C, Kishimoto Y, Schulte-Merker S, Rosa F M. Mech Dev. 2000;99:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00470-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall C J, Flores M V, Davidson A J, Crosier K E, Crosier P S. Dev Biol. 2002;251:105–117. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heasman J, Kofron M, Wylie C. Dev Biol. 2000;222:124–134. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasevicius A, Ekker S C. Nat Genet. 2000;26:216–220. doi: 10.1038/79951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draper B W, Morcos P, Kimmel C B. Genesis. 2001;30:154–156. doi: 10.1002/gene.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Délot E, Kataoka H, Goutel C, Yan Y L, Postlethwait J, Wittbrodt J, Rosa F M. Mech Dev. 1999;85:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruneau S, Rosa F M. Mech Dev. 1997;61:199–212. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]