Abstract

Protein–phosphoinositide interaction participates in targeting proteins to membranes where they function correctly and is often modulated by phosphorylation of lipids. Here we show that protein phosphorylation of p47phox, a cytoplasmic activator of the microbicidal phagocyte oxidase (phox), elicits interaction of p47phox with phosphoinositides. Although the isolated phox homology (PX) domain of p47phox can interact directly with phosphoinositides, the lipid-binding activity of this protein is normally suppressed by intramolecular interaction of the PX domain with the C-terminal Src homology 3 (SH3) domain, and hence the wild-type full-length p47phox is incapable of binding to the lipids. The W263R substitution in this SH3 domain, abrogating the interaction with the PX domain, leads to a binding of p47phox to phosphoinositides. The findings indicate that disruption of the intramolecular interaction renders the PX domain accessible to the lipids. This conformational change is likely induced by phosphorylation of p47phox, because protein kinase C treatment of the wild-type p47phox but not of a mutant protein with the S303/304/328A substitution culminates in an interaction with phosphoinositides. Furthermore, although the wild-type p47phox translocates upon cell stimulation to membranes to activate the oxidase, neither the kinase-insensitive p47phox nor lipid-binding-defective proteins, one lacking the PX domain and the other carrying the R90K substitution in this domain, migrates. Thus the protein phosphorylation-driven conformational change of p47phox enables its PX domain to bind to phosphoinositides, the interaction of which plays a crucial role in recruitment of p47phox from the cytoplasm to membranes and subsequent activation of the phagocyte oxidase.

One of the most dominant themes in current cell biology is acute and sophisticated targeting of proteins to new cellular locations, e.g., to membranes, the nucleus, and so forth. Recruitment of proteins to cell membranes is often triggered by phosphorylation of the lipid phosphatidylinositol (PtdIns), which can create targeting sites for proteins (1, 2). The phosphorylation or hydrolysis of inositol-containing lipids in cell membranes is currently known to orchestrate numerous complex cellular events (3, 4). A variety of protein modules such as pleckstrin homology and FYVE domains recognize specific phosphoinositides (phosphorylated forms of PtdIns) to recruit proteins to appropriate cell membranes (1, 2).

The phagocyte oxidase (phox) homology (PX) domain (5), also known as the phox and Bem1p 2 (PB2) domain (6, 7), occurs in the phox proteins p47phox and p40phox in mammals, the polarity establishment protein Bem1p in budding yeast, and a variety of eukaryotic proteins involved in membrane trafficking. We have determined the NMR structure of the PX domain of p47phox and demonstrated that it interacts with the C-terminal Src homology 3 (SH3) domain of this protein (8). The p47phox PX domain consists of an antiparallel β-sheet formed by three strands and four helices, and an inspection of the molecular surface of the p47phox PX structure reveals a positively charged deep pocket (8) that is supposed to interact with a negatively charged small molecule. Indeed it has been uncovered recently that PX domains function as a phosphoinositide-binding module (9–14). However, it is presently unknown how the lipid-binding activity of PX domains is regulated.

The phagocyte oxidase, dormant in resting cells, becomes activated during phagocytosis to produce superoxide, a precursor of microbicidal oxidants, in consumption with NADPH (6, 15–18). The significance of the NADPH oxidase in host defense is exemplified by recurrent and life-threatening infections that occur in patients with chronic granulomatous disease, the phagocytes of which lack the superoxide-producing system (15–18). The catalytic core of the enzyme is a membrane-integrated flavocytochrome, namely cytochrome b558, comprised of the two subunits gp91phox and p22phox. The activation of the oxidase requires the proteins p47phox and p67phox and the small GTPase Rac, which exist in the cytoplasm of resting phagocytes and translocate after cell stimulation to membranes to interact with the cytochrome, leading to superoxide production (6, 15–19).

It is well established that p47phox plays a central role in membrane translocation of cytosolic factors, an event that is essential for activation of the NADPH oxidase: In chronic granulomatous disease patients with p47phox deficiency, p67phox fails to migrate, whereas p47phox becomes targeted to membranes in stimulated phagocytes from p67phox-defective patients (20). The resting form of p47phox is likely in a closed inactive conformation where its two SH3 domains are masked via an intramolecular interaction with the C-terminal region of this protein (7, 21). Upon cell stimulation, p47phox becomes phosphorylated at the C-terminal quarter, which causes a conformational change that leads to exposure of the SH3 domains (7, 21, 22). The unmasked SH3 domains directly bind to p22phox, an interaction that is required for membrane translocation of p47phox and resultant activation of the oxidase (21, 23). Thus the SH3 domains of p47phox participate in the interaction with p22phox, whereas the C-terminal region negatively regulates the translocation of p47phox via the intramolecular interaction with the SH3 domains. However, the role of the N-terminal PX domain has remained to be elucidated.

Here we show that the PX domain of p47phox exhibits a phosphoinositide-binding activity that is normally suppressed by interacting intramolecularly with the C-terminal SH3 domain. Stimulus-induced phosphorylation of p47phox disrupts the intramolecular interaction to render the PX domain in a state accessible to phosphoinositides, which promotes membrane translocation of this protein and thus plays a crucial role in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. This work provides a previously unknown example of protein phosphorylation eliciting protein–phosphoinositide interaction for its recruitment to membranes.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid Construction and Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins.

The DNA fragment encoding the full-length p47phox or PX domain (p47-PX; amino acids 1–128) was amplified by PCR using a cloned human p47phox cDNA. Mutations leading to the indicated amino acid substitutions were introduced by PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis (7). The DNAs were ligated to pGEX-2T (Amersham Biosciences) and/or pREP4 (Invitrogen) and sequenced for confirmation of their identities. Proteins fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 and purified by glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences) as described (7, 24).

Binding of PX Domain to Liposomes.

The in vitro liposome-binding assay was carried out according to the methods of Patki et al. (25) and Takeuchi et al. (26) with minor modifications (14). Briefly, liposomes were prepared by mixing phosphatidylcholine, PtdIns 4-monophosphate [PtdIns(4)P], PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2], PtdIns 3-monophosphate [PtdIns(3)P], or PtdIns 3,4-bisphosphate [PtdIns(3,4)P2] (purchased from Sigma or Matreya, Pleasant Gap, PA) at the proportions indicated, drying the mixture under nitrogen, and resuspending in a sample buffer (100 mM NaCl/10 mM MgCl2/20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2). Liposomes (100 μM) were incubated with the indicated GST-fusion proteins (100 pmol) in 50 μl of the sample buffer for 10 min at room temperature and collected by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 45 min. The supernatant was removed carefully, and the liposome pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of the sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by 10% SDS/PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. To estimate the amounts of proteins on the gel, densitometric analysis was carried out by using NIH IMAGE software.

Phosphorylation of Recombinant p47phox by Protein Kinase C (PKC).

Phosphorylation of recombinant GST–p47phox was carried out by using human recombinant PKCβ2 (Calbiochem) as described (22). Phosphorylation of p47phox was confirmed by a retarded mobility of the protein on SDS/PAGE and by incorporation of the radioactivity from [γ-32P]ATP as described (22). The protein-phosphatase inhibitor NaF (50 mM) was added to the solution of phosphorylated protein, which was used for the liposome-binding assay.

NMR Spectroscopy.

A uniformly 15N-labeled PX domain of p47phox (amino acids 1–128) was prepared by growing the cells in M9 minimal medium containing 15NH4Cl (1 g/liter) and purifying as described (8). NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C on a Bruker (Billerica, MA) DMX600 spectrometer. The NMR sample contained 0.2 mM p47-PX protein, 5 mM sodium-Mes buffer (pH 5.5), and 5 mM DTT in 95% 1H2O/5% 2H2O. The 1H 15N heteronuclear sequential quantum correlation spectra were recorded in the presence of increasing concentrations of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate or inositol 1,4-bisphosphate up to 1.5 mM (for detail, see Figs. 6 and 7, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). The normalized chemical-shift changes were calculated according to the equation Δδ = {Δδ(1H)2 + [Δδ(15N)/7]2}1/2. Figures were drawn by using the program MOLMOL (27).

Activation of the NADPH Oxidase in a Whole-Cell System.

We transduced both gp91phox and p67phox genes into the leukemic cell line K562 cells as described (7). The pREP4 vector encoding the wild-type full-length p47phox (amino acids 1–390), a full-length mutant p47phox carrying the R90K or S303/304/328A substitution, or a PX-truncated p47phox (p47-ΔPX, amino acids 129–390) was transfected by electroporation to the doubly transduced K562 cells. The K562 cells stably expressing the wild-type or mutant p47phox were selected, and the stable expression in >99% of cells used was confirmed by flow cytometer (FACScan, Becton Dickinson) using anti-p47phox antibody (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). Superoxide production by the K562 cells (1 × 105 cells) in response to 200 ng/ml of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) was determined as superoxide dismutase-inhibitable chemiluminescence detected with an enhancer-containing luminol-based detection system (DIOGENES, National Diagnostics) as described (7, 28).

Membrane Translocation of p47phox.

The K562 cells expressing the wild-type or mutant p47phox protein were suspended at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells per ml in PBS (137 mM NaCl/2.68 mM KCl/1 mM CaCl2/1 mM MgCl2/5 mM glucose/8.1 mM Na2HPO4/1.47 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and stimulated for 10 min at 37°C with PMA (200 ng/ml). After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in relaxation buffer (100 mM KCl/3 mM NaCl/3.5 mM MgCl2/1.25 mM EGTA/20 μM p-amidinophenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride/80 μg/ml leupeptin/20 μg/ml pepstatin A/20 μg/ml chymostatin/10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) and lysed by three rounds of 5-sec sonication. The sonicates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was overlaid on a 10% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion followed by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 30 min. The high-speed supernatant was used as the cytosolic fraction, whereas the high-speed pellet was washed three times with relaxation buffer, suspended in Laemmli sample buffer, and used as the membrane fraction. Proteins were analyzed by Western blot with the anti-p47phox antibody and developed by using ECL-plus (Amersham Biosciences).

Results

The p47phox PX Domain Is Normally Inaccessible to Phosphoinositides via Intramolecular Interaction with the C-Terminal SH3 Domain.

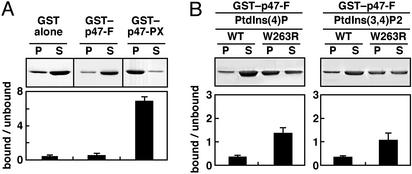

We and others have reported recently that the PX domain of p47phox interacts with various phosphoinositides including PtdIns(4)P, PtdIns(3,4)P2, PtdIns(4,5)P2, and PtdIns(3)P (11, 14), whereas that of p40phox specifically binds to PtdIns(3)P (11, 12, 14). The presence of p47phox in the cytoplasm before cell stimulation suggests that interaction of the p47phox PX domain with membrane phospholipids does not occur in resting cells. Indeed, the full-length wild-type p47phox was incapable of binding to phosphoinositides such as PtdIns(4)P (Fig. 1A) and PtdIns(3,4)P2 (data not shown), whereas an isolated p47phox PX domain did effectively bind to these lipids (Fig. 1A). Thus the PX domain of p47phox seems to be normally inaccessible to phosphoinositides.

Figure 1.

(A) Phosphoinositide-binding activity of the full-length p47phox (p47-F). GST–p47-F, GST–p47-PX, or GST alone was incubated with phospholipids/liposomes containing phosphatidylcholine (90%) and PtdIns(4)P (10%). P and S, liposomal pellet and supernatant after centrifugation, respectively. Samples were analyzed by 10% SDS/PAGE, stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and quantitated by densitometric analysis. The actual bands of GST alone, GST–p47-F, and GST–p47-PX are running at different molecular masses of ≈27, 73, and 40 kDa, respectively. (B) Effect of the W263R substitution on phosphoinositide-binding activity of p47-F. GST–p47-F or GST–p47-F(W263R) was incubated with phospholipids/liposomes containing 10% PtdIns(4)P or PtdIns(3,4)P2. Samples were analyzed as described for A. Each value represents the mean of data from more than three independent experiments, with bars representing the standard deviation.

We have shown recently that the p47phox PX domain interacts intramolecularly with the C-terminal SH3 domain of this protein via the canonical SH3-target PXXP motif (RIIPHLP), and this interaction is abrogated by the amino acid substitution of arginine for the conserved residue Trp-263 in the SH3 domain (8). To elucidate the mechanism that regulates the phosphoinositide-binding activity of the p47phox PX domain, we tested whether the intramolecular interaction prevents the p47phox PX domain from associating with phosphoinositides. The full-length p47phox carrying the W263R substitution in the C-terminal SH3 domain was capable of binding to phosphoinositides such as PtdIns(4)P (Fig. 1B), PtdIns(3,4)P2 (Fig. 1B), and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (data not shown), indicating that the p47phox PX domain in the resting state is likely inaccessible to phosphoinositides via the intramolecular interaction with the C-terminal SH3 domain.

Phosphorylation of p47phox Seems to Cause a Conformational Change That May Render the PX Domain Capable of Binding to Phosphoinositides.

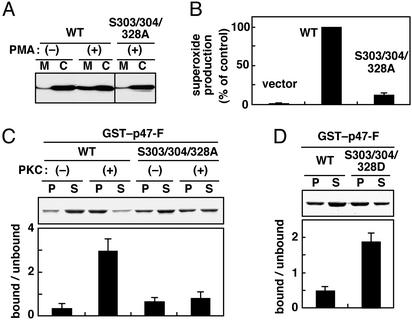

To clarify the mechanism that disrupts the intramolecular interaction between the PX and C-terminal SH3 domains to direct the PX domain toward phosphoinositides, we investigated the effect of phosphorylation of this protein, because it is well established that after cell stimulation p47phox becomes phosphorylated to translocate from the cytoplasm to membranes (29–31). In addition, we have elucidated recently that three serine residues in the C-terminal quarter of p47phox (Ser-303, Ser-304, and Ser-328) are critical for the conformational change leading to the oxidase activation (7, 22). Indeed, when cells were stimulated with PMA, a direct activator of PKC, a mutant p47phox carrying the triple replacement of these serines with the kinase-insensitive alanines (S303/304/328A) failed to translocate to membranes and to activate the NADPH oxidase, whereas the wild-type p47phox became targeted to membranes (Fig. 2A) and fully induced superoxide production (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation-induced conformational change of p47phox, which leads to its interaction with phosphoinositides. (A) Membrane translocation of the wild-type p47phox (WT) and a mutant protein with the S303/304/328A substitution. The gp91phox and p67phox doubly transduced K562 cells were transfected with pREP4 vector or the vector encoding the full-length wild-type p47phox or the one with the S303/304/328A substitution. After cell stimulation with PMA (200 ng/ml), the cell lysates were fractionated by centrifugation, and the cytosolic (C) and membrane (M) fractions were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-p47phox antibody. The actual bands of both wild-type and mutant proteins are running at 47 kDa. (B) Activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase by the wild-type p47phox and a mutant protein with the S303/304/328A substitution. Cells were stimulated with PMA as described for A, and superoxide production was determined by superoxide dismutase-inhibitable chemiluminescence change, monitored with DIOGENES. (C) Effect of phosphorylation of p47phox on its phosphoinositide-binding activity. GST–p47-F (WT) or GST–p47-F (S303/304/328A) was treated with PKC in vitro and incubated with phospholipids/liposomes containing 10% PtdIns(4)P. Samples were analyzed as described for Fig. 1B. The actual bands of both GST-fusion proteins are 74 kDa. (D) Effect of the S303/304/328D substitution of p47phox on its phosphoinositide-binding activity. GST–p47-F(WT) or GST–p47-F(S303/304/328D) was incubated with phospholipids/liposomes containing 10% PtdIns(4)P. Samples were analyzed as described for Fig. 1.

The phosphorylation-induced conformational change of p47phox causes the exposure of the SH3 domains, which are normally masked via an intramolecular interaction; the unmasked SH3 domains bind to p22phox, the small subunit of cytochrome b558 (7, 21, 22). It seems likely that this conformational change also increases the accessibility of the PX domain. As expected, p47phox, which had been phosphorylated in vitro with PKC, was capable of binding to phosphoinositides such as PtdIns(4)P (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, a mutant p47phox with the S303/304/328A substitution could not interact with the lipid even when treated with PKC (Fig. 2C). In addition, a mutant p47phox carrying the simultaneous replacement of the three serines with aspartates (S303/304/328D), mimicking a phosphorylated form (7), was able to bind to PtdIns(4)P without treatment with PKC (Fig. 2D). Thus phosphorylation of p47phox likely induces a conformational change, i.e., a domain rearrangement, which may render the PX domain accessible to phosphoinositides.

Arg-90 Is Present in a Pocket of the p47phox PX Domain and Plays a Crucial Role in Binding to Phosphoinositides.

We finally attempted to answer the question of what the role for the phosphoinositide-binding activity of the p47phox PX domain in the phox activation is. For this purpose, it is necessary to prepare a mutant p47phox protein with an amino acid substitution that leads to a defective interaction with phosphoinositides. To find critical residues of the p47phox PX domain involved in binding to phosphoinositides, we analyzed its interaction with inositol phosphates by NMR.

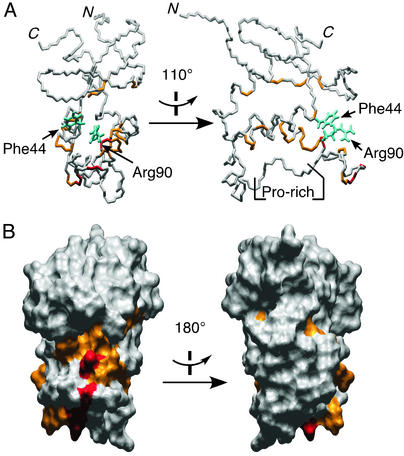

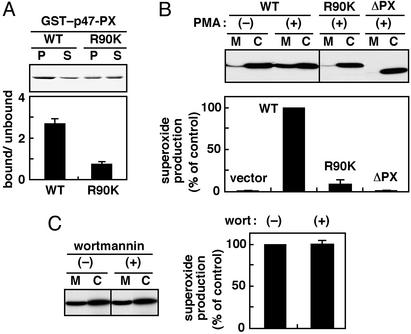

The solution structure of the p47phox PX domain, which we determined recently, consists of three β-strands and four helices (8). An inspection of the molecular surface of the p47phox PX domain structure reveals a positively charged deep pocket (≈8 Å in depth), where the two strongly conserved residues in various PX domains, Arg-90 and Phe-44, are exposed to the solvent (Fig. 3A). Among the residues in the pocket, Arg-90 displayed the largest chemical-shift perturbation in the presence of the inositol phosphate (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting its direct involvement in recognition of polar heads of phosphoinositides. To test this possibility, we prepared a mutant p47phox PX domain and examined its activity in binding to phosphoinositides by the liposome assay. We chose lysine for the substitution for the arginine residue considering the possibility of bidentate nature of the hydrogen-bond interactions between the arginine side chain and the phosphate groups of inositol phosphates. This R90K substitution is more conservative than that of other amino acid residues, e.g., leucine as reported (11), because it does not change the electrostatic property of the molecular surface. To clarify that the substitution does not affect the structural integrity of the domain, we measured the 1H 15N heteronuclear sequential quantum correlation spectrum of the R90K mutant of the p47phox PX domain. The NMR spectrum was essentially the same as that of the wild-type p47phox PX domain (data not shown), confirming the unchanged overall conformation after the R90K substitution. The mutant p47phox PX domain with the R90K substitution bound to PtdIns(3,4)P2 (Fig. 4A) and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (data not shown), but only weakly. Thus, this conserved residue is directly involved in binding to phosphoinositides.

Figure 3.

NMR analysis of the interaction of the p47phox PX domain and inositol phosphate. The normalized chemical-shift changes were calculated after adding 1.5 mM inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate to a sample of 0.2 mM 15N-labeled p47phox PX domain. The residues with 1H 15N crosspeaks that shifted >0.065 ppm are shown in orange (Ile-9, Leu-11, Tyr-26, Phe-44, Thr-53, Lys-55, Glu-56, Trp-80, Ala-87, Gln-91, Gly-92, Thr-93, Leu-94, Glu-96, Tyr-97, and His-113), and those that shifted >0.150 ppm (maximum 0.227 ppm) are shown in red (Phe-81, Gly-83, and Arg-90) on the stick drawing (A) and the molecular surface (B) of the p47phox PX structure (PDB ID code 1GD5). The two conserved residues Phe-44 and Arg-90 involved in the inositol phosphate binding are drawn in cyan. (Left) Viewed in the same orientation. (Right) Rotated 110° (A) and 180° (B) along the vertical axis.

Figure 4.

Role of the p47phox PX domain and its phosphoinositide-binding activity in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. (A) Arg-90 of the p47phox PX domain, which is involved in binding to phosphoinositides. GST–p47-PX or GST–p47-PX (R90K) was incubated with phospholipid/liposomes containing 10% PtdIns(3,4)P2. Samples were analyzed as described for Fig. 1. (B) Membrane translocation of the wild-type p47phox (WT), a mutant protein lacking the PX domain (ΔPX), and the one with the R90K substitution and activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase in cells expressing these proteins. The gp91phox- and p67phox-transduced K562 cells were transfected with pREP4 vector or the vector to express the indicated form of p47phox. (Upper) After cell stimulation with PMA (200 ng/ml), the cell lysates were fractionated by centrifugation, and the cytosolic fraction (C) and membrane fraction (M) were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-p47phox antibody. The actual bands of p47phox-wild type, p47phox-R90K, and p47phox-ΔPX are running at 47, 47, and 45.5 kDa, respectively. (Lower) Superoxide production was determined by superoxide dismutase-inhibitable chemiluminescence change. (C) Effect of wortmannin on membrane translocation and activation of the oxidase. Cells expressing p47phox-wild type were preincubated in the presence or absence of 100 nM wortmannin (wort) and stimulated with PMA (200 ng/ml). Membrane translocation of p47phox (Left) and superoxide production (Right) were analyzed as described for B.

Phosphoinositide-Binding Activity of the p47phox PX Domain Is Essential for Membrane Translocation of This Protein and Activation of the Phagocyte NADPH Oxidase.

Upon cell stimulation, p47phox migrates from the cytoplasm to membranes, an event that is required for activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (15–18). To test the role for the p47phox PX domain, especially the role for its phosphoinositide-binding activity, we expressed a p47phox lacking the PX domain and a full-length one with the R90K substitution in p47phox-deficient K562 cells (7). In response to PMA, an agent that directly stimulates PKC and fully activates the oxidase in cells, the wild-type p47phox translocated to membranes and induced superoxide production (Fig. 4B), whereas the PX-truncated protein could not (Fig. 4B). Intriguingly, the R90K substitution also resulted in a severely impaired translocation and decreased superoxide production (Fig. 4B), indicating that both events require the phosphoinositide-binding activity per se. Thus the p47phox PX domain plays an essential role via its phosphoinositide-binding activity in translocation of this protein to membranes and activation of the NADPH oxidase. In addition, neither translocation of the wild-type p47phox nor the oxidase activation was affected by the PtdIns 3-kinase inhibitors wortmannin (Fig. 4C) and LY294002 (data not shown), indicating that the lipid kinase does not regulate both events in PMA-stimulated K562 cells.

Discussion

In the present study we show that although the isolated PX domain of p47phox can interact directly with phosphoinositides, the lipid-binding activity of this protein is normally suppressed by intramolecular interaction of the PX domain with the C-terminal SH3 domain. Stimulus-induced phosphorylation of p47phox disrupts the intramolecular interaction to direct the PX domain toward phosphoinositides. Resultant interaction of the PX domain with the phospholipids promotes membrane translocation of p47phox and thus plays an essential role in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Hence the protein phosphorylation-driven conformational change of p47phox regulates the phosphoinositide-binding activity of the PX domain, which determines the localization of this protein, thereby serving as a switch for the oxidase.

The PX domain is thus required but does not seem sufficient for membrane translocation of p47phox, because the isolated p47phox PX domain neither binds to cell membranes in resting cells nor translocates to cell membranes in PMA-stimulated cells (R.T. and H.S., unpublished data). This may be due to the fact that it only binds weakly to phosphoinositides compared with other PX domains (ref. 11 and R.T. and H.S., unpublished data).

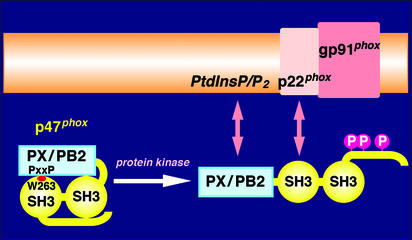

We have shown previously that the SH3 domains of p47phox are masked in the resting state (21, 32) and that phosphorylation causes a conformational change that renders the SH3 domains capable of specifically interacting with p22phox, an interaction that also is essential for membrane translocation of p47phox and thus for the oxidase activation (7, 22). Taken together with the present findings, we propose a previously uncharacterized mechanism underlying the regulation of p47phox in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase (Fig. 5). Stimulus-induced phosphorylation of p47phox causes a conformational change, by which both PX and SH3 domains become accessible to their membranous targets, phosphoinositides and p22phox, respectively. Cooperation of these two interactions, each being indispensable but not sufficient, enables p47phox to form a stable complex with cytochrome b558, leading to activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase.

Figure 5.

A proposed mechanism underlying the regulation of p47phox in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Human p47phox comprises 390 amino acid residues, and PX/PB2 represents the PX domain (5), also called the PB2 domain (6, 7). The C-terminal SH3 domain, containing Trp-263, interacts intramolecularly with the PXXP motif of the PX domain. Stimulus-induced phosphorylation of p47phox causes a conformational change, by which both PX and SH3 domains become accessible to their membranous targets, phosphoinositides and p22phox, respectively. Cooperation of these two interactions, each being indispensable, enables p47phox to form a stable complex with cytochrome b558 (composed of the two subunit gp91phox and p22phox), leading to activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase.

The present findings indicate that the p47phox PX domain in the resting state is inaccessible to phosphoinositides via its intramolecular interaction with the C-terminal SH3 domain. This effect on the PX domain may be due to the fact that the SH3 domain directly masks the phosphoinositide-binding pocket or that the SH3 domain attenuates the PX–phosphoinositide interaction in an allosteric fashion. Data from our structural analyses prefer the latter explanation. We reported recently that chemical-shift changes are observed throughout the p47phox PX structure when the p47phox C-terminal SH3 domain interacts with the proline-rich segment of the PX domain, suggestive of an SH3 domain-induced conformational change (8). In particular, Arg-90 and Phe-44 in the inositol phosphate-binding pocket are influenced by the interaction with the SH3 domain. In the present study, we performed another NMR titration experiment in which the addition of inositol phosphates to a solution of the p47phox PX domain caused chemical-shift changes of several residues (Ile-9, Leu-11, Thr-53, Lys-55, Glu-56, and His-113) distant from the binding pocket (Fig. 3), suggesting that a change of the PX domain conformation is induced by the inositol phosphate binding. Consistent with this, it is suggested that conformational changes of the PX domain of the yeast vacuole protein Vam7p accompany its interaction with PtdIns(3)P (9). Thus, the two PX ligands, i.e., inositol phosphates and the p47phox C-terminal SH3 domain, seem to mutually influence the other's binding through conformational changes of the p47phox PX domain. A similar SH3 domain-mediated regulation may occur in other PX domain-containing proteins that also harbor SH3 domains such as Bem1p and p40phox (32).

Phosphorylation-mediated membrane association is also observed in other PX-containing proteins such as mammalian phospholipase D1 (33, 34) and its yeast homologue Spo14p (35), raising the possibility that the translocation also may be mediated by the PX domain and regulated by protein phosphorylation. On the other hand, in some cases the interaction of the PX domain with phosphoinositides could be constitutive rather than inducible. It has been shown that sorting nexins (36, 37) and the class II PtdIns 3-kinases (38) localized in the membrane fraction without cell stimulation, suggesting that their PX domains may interact constitutively with phosphoinositides.

This study provides a previously unknown example that protein–phosphoinositide interaction is elicited by protein phosphorylation. It seems evident that changes in the levels of phosphoinositides such as PtdInsP3 and PtdInsP2 are not involved in the interaction of p47phox with phosphoinositides, at least in PMA-stimulated cells, because PMA does not affect the levels of the lipids (39, 40), and PtdIns 3-kinase inhibitors do not affect membrane translocation of p47phox in PMA-stimulated cells (Fig. 4C). In contrast, in other known cases, a kinase or phosphatase for the inositol-containing lipids modulates interaction between lipids and proteins by producing specific phosphoinositides (1, 2). Although the association of p47phox with phosphoinositides is thus primarily regulated by protein phosphorylation, it is also possible that PtdIns 3-kinase can enhance the membrane recruitment in neutrophils stimulated with chemoattractants such as formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP): The PX domain of p47phox is capable of binding to PtdIns(3,4)P2, a product of the lipid kinase, with high preference (11, 14). It is well known that fMLP efficiently activates PtdIns 3-kinase in neutrophils, and fMLP-elicited superoxide production is inhibited by PtdIns 3-kinase inhibitors (39–41).

It also should be noted that the PX domain of p40phox preferentially binds to PtdIns(3)P, whereas the p47phox PX domain prefers other phosphoinositides such as PtdIns(4)P and PtdIns(3,4)P2 (11, 12, 14). Because both proteins are tightly associated in the same protein complex in resting cells and simultaneously migrate to membranes upon cell stimulation (6, 15–19), the difference in phosphoinositide specificity may suggest that the two PX domains associate with distinct types of membranes to facilitate a membrane fusion, which is expected to proceed during phagocytosis when the NADPH oxidase becomes activated. This possibility should be tested in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Masato Hirata (Kyushu University) and Dr. Kazuhisa Ota (Kanazawa University) for helpful comments, and Yohko Kage (Kyushu University) for excellent technical assistance. This work was partly supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan, ONO Medical Research Foundation, and the BIRD project of the Japan Science and Technology Corporation.

Abbreviations

- PtdIns

phosphatidylinositol

- phox

phagocyte oxidase

- PX

phox homology

- SH3

Src homology 3

- PtdIns(4)P

PtdIns 4-monophosphate

- PtdIns(4,5)P2

PtdIns 4,5-bisphosphate

- PtdIns(3)P

PtdIns 3-monophosphate

- PtdIns(3,4)P2

PtdIns 3,4-bisphosphate

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Fruman D A, Rameh L E, Cantley L C. Cell. 1999;97:817–820. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corvera S, D'Arrigo A, Stenmark H. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:460–465. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corvera S, Czech M P. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:442–446. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rameh L E, Cantley L C. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8347–8350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponting C P. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2353–2357. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sumimoto H, Ito T, Hata K, Mizuki K, Nakamura R, Kage Y, Nakamura M, Sakaki Y, Takeshige K. In: Membrane Proteins: Structure, Function and Expression Control. Hamasaki N, Mihara K, editors. Basel: Karger; 1997. pp. 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ago T, Nunoi H, Ito T, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33644–33653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiroaki H, Ago T, Ito T, Sumimoto H, Kohda D. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;6:526–530. doi: 10.1038/88591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheever M L, Sato T K, de Beer T, Kutateladze T G, Emr S D, Overduin M. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:613–618. doi: 10.1038/35083000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu Y, Hortsman H, Seet L, Wong S H, Hong W. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:658–666. doi: 10.1038/35083051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanai F, Liu H, Field S J, Akbary H, Matsuo T, Brown G E, Cantley L C, Yaffe M B. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:675–678. doi: 10.1038/35083070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellson C D, Gobert-Gosse S, Anderson K E, Davidson K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Thuring J W, Cooper M A, Lim Z-Y, Holmes A B, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:679–682. doi: 10.1038/35083076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song X, Xu W, Zhang A, Huang G, Liang X, Virbasius J V, Czech M P, Zhou G W. Biochemistry. 2001;40:8940–8944. doi: 10.1021/bi0155100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ago T, Takeya R, Hiroaki H, Kuribayashi F, Ito T, Kohda D, Sumimoto H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:733–738. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeo F R, Quinn M T. J Leukocyte Biol. 1996;60:677–691. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babior B M. Blood. 1999;93:1464–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nauseef W M. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111:373–382. doi: 10.1111/paa.1999.111.5.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark R, A. J Infect Dis. 1999;179, Suppl. 2:S309–S317. doi: 10.1086/513849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito T, Matsui Y, Ago T, Ota K, Sumimoto H. EMBO J. 2001;20:3938–3946. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyworth P G, Curnutte J T, Nauseef W M, Volpp B D, Pearson D W, Rosen H, Clark R A. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:352–356. doi: 10.1172/JCI114993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumimoto H, Kage Y, Nunoi H, Sasaki H, Nose T, Fukumaki Y, Ohno M, Minakami S, Takeshige K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5345–5349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiose A, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33644–33653. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leto T L, Adams A G, de Mendez I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10650–10654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noda Y, Takeya R, Ohno S, Naito S, Ito T, Sumimoto H. Genes Cells. 2001;6:107–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patki V, Virbasius J, Lane W S, Toh B-H, Shpetner H S, Corvera S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7326–7330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi H, Matsuda M, Yamamoto T, Kanamatsu T, Kikkawa U, Yagisawa H, Watanabe Y, Hirata M. Biochem J. 1998;334:211–218. doi: 10.1042/bj3340211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:52–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koga H, Terasawa H, Nunoi H, Takeshige K, Inagaki F, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25051–25060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Benna J, Faust L P, Babior B M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23431–23436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inanami O, Johnson J L, McAdara J K, El Benna J, Faust L R P, Newburger P E, Babior B M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9539–9543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J, Kleinberg M E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19731–19737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hata K, Ito T, Takeshige K, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4232–4236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sung T C, Zhang Y, Morris A J, Frohman M A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3659–3666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim Y, Han J M, Park J B, Lee S D, Oh Y S, Chung C, Lee T G, Kim J H, Park S-K, Yoo J-S, et al. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10344–10351. doi: 10.1021/bi990579h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudge S A, Morris A J, Engebrecht J. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:81–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurten R C, Cadena D L, Gill G N. Science. 1996;272:1008–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haft C R, de la Luz Sierra M, Barr V A, Haft D H, Taylor S I. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7278–7287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arcaro A, Volinia S, Zvelebil M J, Stein R, Watton S J, Layton M J, Gout I, Ahmadi K, Downward J, Waterfield M D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33082–33090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.33082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Traynor-Kaplan A E, Thompson B L, Harris A L, Taylar P, Omann G M, Sklar L A. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15668–15673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stephens L, Eguinoa A, Corey S, Jackson T, Hawkins P T. EMBO J. 1993;12:2265–2273. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akasaki T, Koga H, Sumimoto H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18055–18059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.