Inherited thrombophilias affect over 16% of people and predispose them to venous thromboembolism.1 Pre-eclampsia is associated with occlusion of the placental spiral arteries.2 Thrombophilias may cause thrombosis of placental vessels,3 thereby explaining the link between thrombophilia and pre-eclampsia.4,5 We tested the hypothesis that women with pre-eclampsia have a higher risk of subsequent venous thromboembolism.

Participants, methods, and results

The study was approved by our research ethics board and took place in Ontario, Canada, where all hospital services are publicly funded. We used an administrative database that is based on anonymised populations and which records all hospitalisations from 1 April 1988 onwards. All discharges between 1 April 1990 and 1 January 1994 with a primary ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision) code of pre-eclampsia, severe pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, or toxaemia were identified (see appendix A on bmj.com). These codes had a sensitivity of 89% (95% confidence interval 78% to 94%) and a specificity of 67% (79% to 94%) for patients with true pre-eclampsia (appendix B).

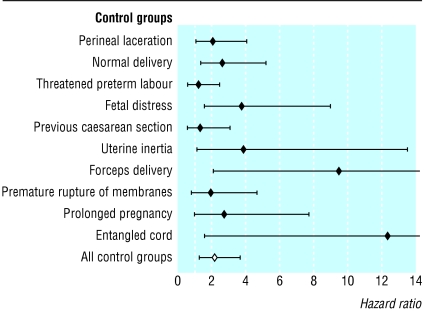

We used multiple control groups consisting of women with the 10 most common primary obstetrical diagnoses at time of discharge (appendix A; see figure). We determined from the hospitalisation database whether patients had had a caesarean section during their index hospitalisation. If they had had one or more admissions for pre-eclampsia, they were assigned to the pre-eclampsia group. Patients were excluded if they were less than 15 years old or if they were admitted to hospital for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (appendix A) before entering the study. These admissions were also identified in the hospitalisations database.

The observation period started when patients were discharged from their index hospitalisation and ended at study end (1 January 1995), when patients died, or when patients were admitted with venous thromboembolism. We chose 1995 as study end because until 1995 patients with thromboembolism were initially treated in hospital with unfractionated heparin. This ensures that virtually all such patients were admitted to hospital and identified in the hospitalisation database (appendix C). Dates of death were determined from the registered patient database that records all deaths in Ontario.

During the study period, 297 912 women were discharged from hospital with one of the study diagnoses. Some were excluded because they were under 15 or had previous thromboembolic disease (n=703 and n=172, respectively). This left 12 849 women in the pre-eclampsia group and 284 188 women in the control groups (range 11 188 to 22 883). Patients with pre-eclampsia were younger (mean 27.8 v 28.1) and more likely to have had a caesarean section (20.0% v 10.6%). Mean follow up was three years.

Venous thromboembolism was more common in the pre-eclampsia group (0.12%, 41.7 events per 100 000 person years observation) than in any of the control groups (range 0.01% to 0.08%, rates of 3.0 to 33.8 events per 100 000 person years observation). We used proportional hazards modelling to control for patient age and caesarean section, and showed that, compared with all control groups combined, women with pre-eclampsia were 2.2 times more likely (95% confidence interval 1.3 to 3.7) to be admitted to hospital with venous thromboembolism (figure). The proportional hazards assumption was valid for all models.

Comment

Women with pre-eclampsia have a small but significantly higher risk of subsequent venous thromboembolic disease compared with women diagnosed as having other common obstetrical diseases. Our results support the association between pre-eclampsia and thrombophilia.

The absolute risk increase with pre-eclampsia is too small to warrant venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for such patients. The signs and symptoms of venous thromboembolism should be reviewed with women who develop or have had pre-eclampsia so that they can seek appropriate medical care if the need arises.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Independent risk of venous thromboembolism for women with pre-eclampsia. The adjusted hazard ratio for admission to hospital with deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is presented for women with pre-eclampsia compared with the 10 most common obstetrical discharge diagnoses. The hazard ratios (shown here with 95% confidence intervals) are adjusted for patient age and whether a caesarean section was performed at the index admission

Footnotes

Funding: CvW and MW are Ontario Ministry of Health career scientists.

Competing interests: None declared.

More information on ICD-9 codes can be found on bmj.com

References

- 1.Rodeghiero F, Tosetto A. The epidemiology of inherited thrombophilia: the VITA Project. Vicenza Thrombophilia and Atherosclerosis Project. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redman CW. Platelets and the beginnings of preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:478–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008163230710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gris JC, Ripart-Neveu S, Maugard C, Tailland ML, Brun S, Courtieu C, et al. Respective evaluation of the prevalence of haemostasis abnormalities in unexplained primary early recurrent miscarriages. The Nimes obstetricians and haematologists (NOHA) study. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:1096–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grandone E, Margaglione M, Colaizzo D, Cappucci G, Paladini D, Martinelli P, et al. Factor V Leiden, C > T MTHFR polymorphism and genetic susceptibility to preeclampsia. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:1052–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kupferminc MJ, Eldor A, Steinman N, Many A, Bar-Am A, Jaffa A, et al. Increased frequency of genetic thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.