Abstract

The Arabidopsis SLY1 (SLEEPY1) gene positively regulates gibberellin (GA) signaling. Positional cloning of SLY1 revealed that it encodes a putative F-box protein. This result suggests that SLY1 is the F-box subunit of an SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase that regulates GA responses. The DELLA domain protein RGA (repressor of ga1-3) is a repressor of GA response that appears to undergo GA-stimulated protein degradation. RGA is a potential substrate of SLY1, because sly1 mutations cause a significant increase in RGA protein accumulation even after GA treatment. This result suggests SCFSLY1-targeted degradation of RGA through the 26S proteasome pathway. Further support for this model is provided by the observation that an rga null allele partially suppresses the sly1-10 mutant phenotype. The predicted SLY1 amino acid sequence is highly conserved among plants, indicating a key role in GA response.

INTRODUCTION

Bioactive gibberellins (GAs) are tetracyclic diterpenoid phytohormones required for germination, stem elongation, induction of flowering, and fertility (Richards et al., 2001). Severe mutants defective in GA biosynthesis (e.g., the deletion of the GA1 gene in ga1-3) display failure to germinate, dwarfism, delayed flowering, and reduced fertility. All of these phenotypes are rescued by GA treatment. By contrast, mutants impaired in GA signaling display similar phenotypes but are not rescued by GA.

Elements of the GA response pathway in Arabidopsis have been defined through the genetic analysis of mutants (Richards et al., 2001; Olszewski et al., 2002). Positive regulators of GA signaling include SLY1 (SLEEPY1) and PKL (PICKLE). PKL encodes a putative chromatin-remodeling factor, CHD3 (Ogas et al., 1999). Recessive mutations in this gene result in adult plants in which the primary root meristem retains embryonic characteristics. This phenotype is enhanced by GA biosynthetic inhibitors.

Negative regulators of GA signaling include SHI, SPY, RGA, GAI, RGL1, and RGL2. Overexpression of the SHI (SHORT INTERNODES) gene results in a GA-insensitive semidwarf phenotype. The predicted SHI gene product is homologous with the RING-finger domain that mediates protein–protein interaction in ubiquitylation and transcription (Fridborg et al., 1999, 2001). Loss of SPY (SPINDLY) function results in a GA-overdose phenotype that includes increased internode length, parthenocarpy, and increased resistance to the GA biosynthetic inhibitor paclobutrazol during vegetative growth and germination (Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993). SPY encodes an O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) (Jacobsen et al., 1996; Swain et al., 2002). OGTs may regulate the target protein function by competing with protein kinases for modification of phosphorylation sites. RGA (REPRESSOR OF GA1-3) and GAI (GA-INSENSITIVE) encode members of the DELLA (VHIID) domain subfamily of the GRAS family of putative transcription regulators (Richards et al., 2001; Olszewski et al., 2002; Peng and Harberd, 2002). Loss of RGA or GAI function results in decreased sensitivity to the GA biosynthetic inhibitor paclobutrazol during vegetative growth. Conversely, mutations in the DELLA domain of GAI and RGA result in a gain-of-function (semidominant) semidwarf phenotype (Peng et al., 1997; Dill et al., 2001). RGA and GAI share 83% amino acid identity and act as GA-repressible repressors of stem elongation in Arabidopsis (Dill and Sun, 2001; King et al., 2001). Recent evidence shows that RGA protein accumulation decreases in response to GA treatment. This finding suggests that RGA is subject to GA-induced proteolysis (Silverstone et al., 2001). Other members of the DELLA gene family in Arabidopsis include RGL1, RGL2, and RGL3 (RGA-LIKE) (Sanchez-Fernandez et al., 1998). RGL2 is a negative regulator of germination whose transcript levels are increased transiently during dormant seed imbibition (Lee et al., 2002). RGL1 appears to be a negative regulator of more diverse GA responses, including germination, stem elongation, leaf expansion, flowering, and flower development (Wen and Chang, 2002).

The DELLA family of GA response genes is a highly conserved gene family of considerable agronomic importance (Peng et al., 1999). Introduction of DELLA domain semidwarf mutations into crop plants resulted in the 16 to 31% increase in yield referred to as the Green Revolution (Allan, 1986; Peng et al., 1999). These genes are negative regulators of GA response. Loss of function leads to increased GA signaling, whereas gain of function results in reduced GA signaling and dwarfism. Although there are five members of the DELLA family in Arabidopsis, there is only a single DELLA gene in rice (SLR1 [SLENDER-RICE]) and in barley (SLN1 [SLENDER]). Like RGA, both SLR1 and SLN1 apparently are subject to GA-regulated proteolysis (Chandler et al., 2002; Gubler et al., 2002; Itoh et al., 2002). Recently, proteolysis of SLN1 was shown to depend on the 26S proteasome, indicating a role for ubiquitin in GA signal transduction (Fu et al., 2002).

The sly1 mutants were isolated as recessive GA-insensitive dwarf mutants in two independent screens based on their increased seed dormancy, a property expected in a GA response mutant. The first screen recovered the ethyl methanesulfonate–induced sly1-2 allele that suppressed the ability of abi1-1 (abscisic acid–insensitive) to germinate on 3 μM abscisic acid. The second screen identified sly1-10 based on brassinosteroid-dependent germination (Steber et al., 1998; Steber and McCourt, 2001). Loss of SLY1 function results in all of the phenotypes expected of a GA response mutant, including increased seed dormancy, growth as a dark green dwarf, delayed flowering, and reduced fertility.

Here, we report map-based cloning of the SLY1 gene, a putative F-box subunit of an SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase. A BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search revealed SLY1 homologs in many plant species, suggesting that its role as a positive regulator of GA response also is conserved. In addition, mutations in SLY1 resulted in high-level RGA protein accumulation even in the presence of GA. This result indicates that the SLY1 gene is needed for the GA-stimulated proteolysis of RGA. The dwarf phenotype of sly1 plants is suppressed by the rga-24 null mutation. Thus, accumulation of high levels of RGA is required for expression of the dwarf phenotype of sly1 mutants. These results suggest that an SCFSLY1 complex mediates the GA-induced degradation of RGA.

RESULTS

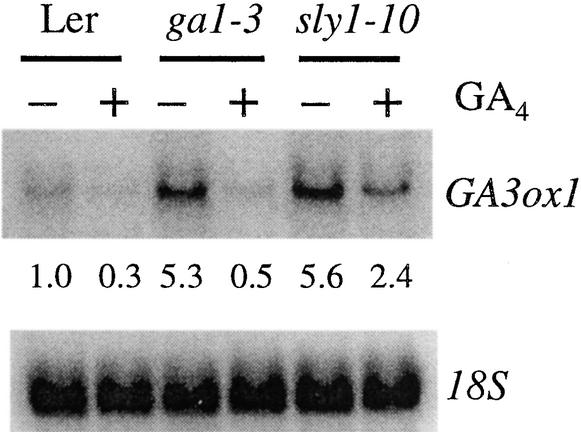

Effect of the sly1-10 Mutant on GA3ox1 Expression

GA biosynthesis is subject to feedback regulation. Decreased GA biosynthesis or response results in increased mRNA accumulation for most of the late GA biosynthetic genes that encode GA-20 oxidase (GA20ox) and GA-3 oxidase (GA3ox), whereas the application of exogenous GA results in decreased expression of the same GA biosynthetic genes (reviewed by Hedden and Phillips, 2000). Because mutations in SLY1 result in reduced GA response, we would expect increased expression of these GA biosynthetic genes in the sly1-10 mutant. To test this hypothesis, we compared the transcript accumulation of one of the GA-3 oxidase genes in Arabidopsis, GA3ox1, in the wild type, ga1-3, and sly1-10 (Figure 1). As shown previously, in the absence of GA, GA3ox1 transcript levels were fivefold higher in the severe GA biosynthetic mutant ga1-3 than in the wild type (Chiang et al., 1995; Cowling et al., 1998; Yamaguchi et al., 1998). Similar to ga1-3, the sly1-10 mutant accumulated fivefold greater GA3ox1 mRNA levels compared with the wild type in the absence of exogenous GA. Application of GA4 resulted in a 10-fold decrease in GA3ox1 expression in ga1-3 but only a 2-fold decrease in sly1-10. This result indicates that the sly1-10 mutant retains some residual sensitivity to GA4.

Figure 1.

Effect of sly1 Mutations on GA3ox1 Transcript.

An RNA gel blot, containing 10 μg of total RNA isolated from 8-day-old Ler (wild-type), ga1-3, and sly1-10 seedlings treated with (+) or without (−) 1 μM GA4 for 2 h, was hybridized with a labeled AtGA3ox1 antisense RNA probe. The blot was reprobed with a labeled 18S oligonucleotide probe. Numerals below the blot indicate the relative levels of AtGA3ox1 mRNA after standardization using the 18S RNA as a loading control. The level of AtGA3ox1 mRNA in the water-treated wild type was arbitrarily set to 1.0.

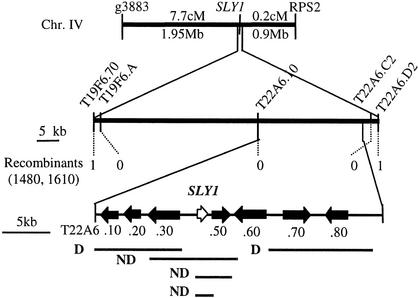

Map-Based Cloning of SLY1

The SLY1 gene was cloned using a map-based approach to further elucidate its function in GA signal transduction. The sly1-2/sly1-2 mutant in the Landsberg erecta (Ler) ecotype was crossed to wild-type ecotype Columbia to generate an F2 mapping population of sly1-2/sly1-2 plants segregating for Ler- and Columbia-specific physical markers. sly1-2/sly1-2 F2 seeds were germinated by cutting the seed coats. As a result of the poor germination and poor fertility of sly1-2, all mapping was performed relative to PCR-based physical markers that differ between the two ecotypes (Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993; Bell and Ecker, 1994). SLY1 was 7.7 centimorgan (cM) from g3883 and 0.2 cM from RPS2 (Figure 2). RPS2 was used as a point from which to begin a chromosome walk toward g3883. A population of 805 sly1-2/sly1-2 F2 plants (1610 chromosomes) was scored for the RPS2 cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence marker (Bent et al., 1994). Four F2 plants heterozygous for the RPS2 marker were recovered and used as a basis for a chromosome walk of 0.9 Mb. The recombination rate across this region was very low, with a ratio of 4500 kb/cM compared with the Arabidopsis average of 200 kb/cM (Schmidt et al., 1995). SLY1 was localized to a 70-kb region between markers T19F6.7 and T22A6.D2.

Figure 2.

Map-Based Cloning of SLY1.

Fine mapping delineated a 70-kb region containing SLY1 between markers T19F6.70 and T22A6.D2. Single recombination events were identified at T22A6.D2 (in 1610 chromosomes) and at T19F6.70 (in 1480 chromosomes). Overlapping BAC clones T22A6 and T19F6 cover this region (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000). Transformation with subclones of these BACs identified an 11.7-kb complementing subclone, T22A6.2G10. Transformation with T22A6.40 (from −1347 to +666 relative to the ATG) rescued sly1. D, dwarf; ND, nondwarf.

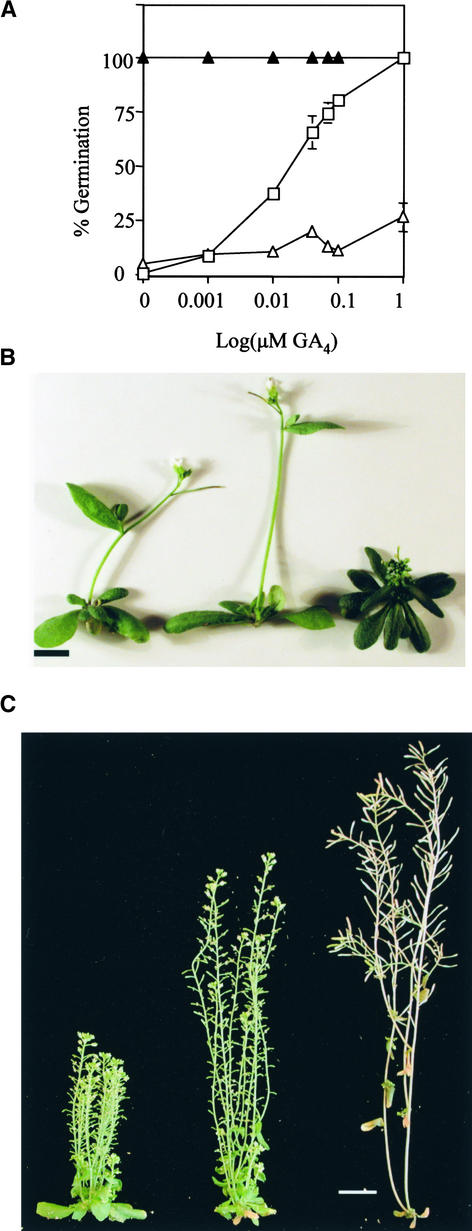

There were 20 predicted genes in the 70-kb region containing SLY1 (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000). Transformation of sly1-2 and sly1-10 plants with BAC subclones revealed that an 11.7-kb subclone, T22A6.2G10, rescued the dwarf (data not shown) and germination (Figure 3A) phenotypes of sly1 mutants. This subclone contains three predicted open reading frames (ORFs): T22A6.30 (At4g24200), T22A6.40 (At4g24210), and T22A6.50 (At4g24220). Transformation with the T22A6.40 ORF alone rescued the sly1-10 mutant phenotypes (Figure 3B). DNA sequence analysis of sly1-2 and sly1-10 revealed that these alleles contain mutations within this 453-bp ORF (Figure 4A). sly1-2 has a 2-bp deletion (Cys-337 and Thr-338) that causes a frameshift that eliminates the last 40 amino acids. sly1-10 contains a 23-bp deletion (amino acids 433 to 456) followed by an ∼8-kb insertion. This causes the loss of only the last 8 amino acids and the addition of 46 random amino acids. Thus, T22A6.40 (At4g24210) is the SLY1 gene. SLY1 contains no introns and encodes a small predicted protein of 151 amino acids containing a putative F-box domain.

Figure 3.

Complementation of sly1 Mutants.

(A) GA dose response in germination. Transformation with the T22A6.2G10 subclone rescues the GA-insensitive germination phenotype of sly1-2. Percentage germination of dormant sly1-2 seeds (open triangles), the GA biosynthesis mutant ga1-3 (open squares), and sly1-2 transformed with T22A6.2G10 (closed triangles) is shown. Wild-type Ler germination was identical to that of T22A6.2G10-transformed sly1-2. Error bars represent standard errors for triplicate samples of 50 to 100 seeds.

(B) Transformation with T22A6.40 (−1347 to +666) rescues the dwarf phenotype of sly1-2. Wild-type Ler (left), sly1-2+ T22A6.40 (center), and sly1-2 (right) plants are shown. Bar = 1 cm.

(C) Suppression of sly1-10 by rga-24. sly1-10 (left), the sly1-10 rga-24 double mutant (center), and wild-type Ler (right) plants are shown. rga-24 partly rescues the dwarf phenotype of sly1-10, but not poor fertility. Ler and homozygous mutant plants were grown on soil for 60 days under a long-day photoperiod. Bar = 15 mm.

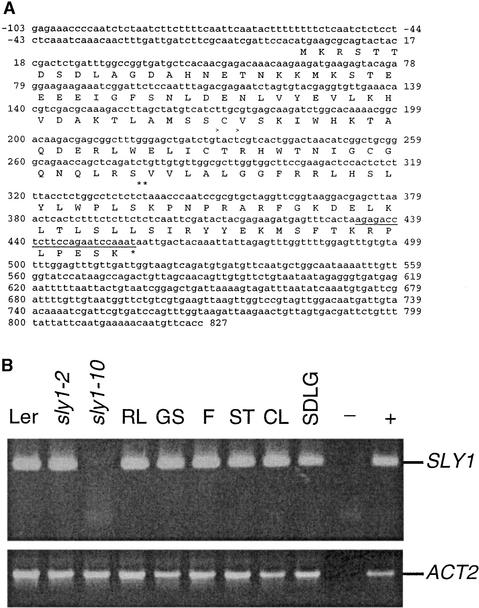

Figure 4.

SLY1 mRNA.

(A) Sequence of full-length SLY1 cDNA. The SLY1 gene contains no introns and predicts a protein of 151 amino acids. The first ATG (+1) in the transcript is the SLY1 translational start site. sly1-2 contains a 2-bp deletion (double asterisks). sly1-10 contains a 23-bp deletion (underlined) and an 8-kb insertion.

(B) RT-PCR analysis of SLY1 mRNA accumulation. An ethidium bromide–stained 2% agarose gel from RT-PCR using 100 ng of total RNA for each sample is shown. SLY1 (250 bp) plus ACT2 (471 bp) accumulation are shown for wild-type Ler, sly1-2, and sly1-10 whole aerial plants and for wild-type Ler rosette leaves (RL), green siliques (GS), flowers (F), stems (ST), cauline leaves (CL), and seedlings (SDLG). For seedlings, tissue was harvested from 4-week-old plants. −, no RNA template; +, genomic DNA.

Expression of SLY1

Sequencing of several full-length SLY1 cDNAs identified 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of 87 and 105 nucleotides (Figure 4A) (http://signal.salk.edu/). The major ORF in this transcript is the SLY1 gene. The long 380-nucleotide 3′ UTR shows a high probability of secondary structure (99.6 kcal/mol) according to Vienna RNA secondary structure prediction (http://www.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi). The Arabidopsis F-box gene TIR1 mRNA also contains a long structured 3′ UTR. Structured 3′ UTRs have been implicated in the control of mRNA stability and localization (Decker and Parker, 1995). Reverse transcriptase–mediated (RT) PCR analysis of wild-type Ler plants showed that the SLY1 transcript is present in all tissues examined (Figure 4B), including rosette leaves, green siliques, flowers, stems, cauline leaves, and seedlings. The SLY1 mRNA was not detected in the sly1-10 mutant, as a result of an 8-kb insertion within the PCR product. However, a band of 9 kb was detected in sly1-10 but not in wild-type Ler by RNA gel blot analysis, indicating that the gene is still expressed (data not shown).

Analysis of the SLY1 Gene Structure

A BLAST search revealed that the predicted SLY1 protein sequence is homologous with the cyclin F-box family of proteins (Figure 5A) (Altschul et al., 1990; Zhang et al., 1998; Gagne et al., 2002). The F-box protein is one of the four main subunits of the SCF (SKP1, Cullin, F-box) complex, one type of E3 ubiquitin ligase (Conaway et al., 2002). The F-box subunit directs the interaction of the complex with a specific target for ubiquitylation. Thus, SLY1 may transduce the GA signal by regulating the stability of GA response proteins through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis.

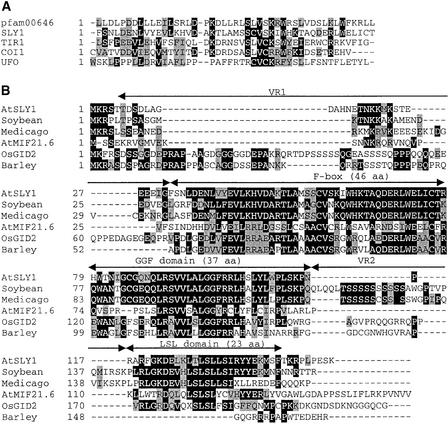

Figure 5.

SLY1 Sequence Alignments.

(A) Alignment of the SLY1 F-box with National Center for Biotechnology Information consensus Pfam00646 (an F-box protein family) and other Arabidopsis F-box proteins.

(B) Alignment of SLY1 with plant homologs from soybean, Medicago truncatula, Arabidopsis MIF21.6, rice OsGID2, and barley. The amino acid sequence predicted from the largest open reading frame in each EST is listed. GGF and LSL refer to conserved residues. aa, amino acids; VR, variable region.

SCF-mediated proteolysis regulates many aspects of plant development, including senescence, flower development, circadian rhythm, light receptor signaling, and hormone signaling (Hellmann and Estelle, 2002). The SCFTIR1 and SCFCOI1 complexes are needed for auxin and jasmonate signal transduction, respectively (Gray et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2002). SCFTIR1 controls AXR2/IAA7 stability and is the only SCF in Arabidopsis for which a target has been identified to date (Gray et al., 2001). The predicted TIR1 and COI1 F-box proteins share 34% amino acid identity with each other and contain an F-box at the N terminus and a Leu-rich repeat domain at the C terminus. The predicted SLY1 protein is not homologous with these proteins outside of the F-box motif. F-box proteins often contain a C-terminal protein–protein interaction domain, such as Leu-rich repeats, WD40 repeats, or Kelch repeats, for interaction with its target protein (del Pozo and Estelle, 2000). Although SLY1 lacks such a conserved protein–protein interaction domain, its C terminus clearly is important for function. Both sly1-2 and sly1-10 alleles leave the F-box intact but alter the C terminus (Figure 4A). Other examples of F-box proteins lacking a conserved C-terminal protein–protein interaction domain include the mammalian gene Fbx8 and the Arabidopsis gene SON1 (Cenciarelli et al., 1999; Ilyin et al., 2000; Kim and Delaney, 2002).

SLY1 is highly conserved in the plant kingdom. Many members of the SLY1 gene family were identified by tBLASTn search of plant ESTs (Figure 5B). Although homologs were detected in many plant species, none were detected outside of the plant kingdom. Amino acid relatedness with the predicted SLY1 protein ranged from 57% identical/67% similar in the dicot soybean to 42% identical/57% similar in the monocot barley. The rice ortholog of SLY1 was identified independently by Sasaki et al. (2003) by positional cloning of GID2 (GA-INSENSITIVE DWARF). GID2 encodes a predicted 212–amino acid protein that is 43% identical and 56% similar to SLY1. The regions of highest amino acid identity are the F-box and the 37–amino acid GGF region (Figure 5B). Two variable regions (Figure 5B, VR) are absent in AtSLY1. A BLAST search detected a single SLY1 homolog (154 amino acids, 26% identical) in Arabidopsis, MIF21.6 (At5g48170), on chromosome V (Figure 5B).

Accumulation of RGA Is Increased in sly1 Mutants

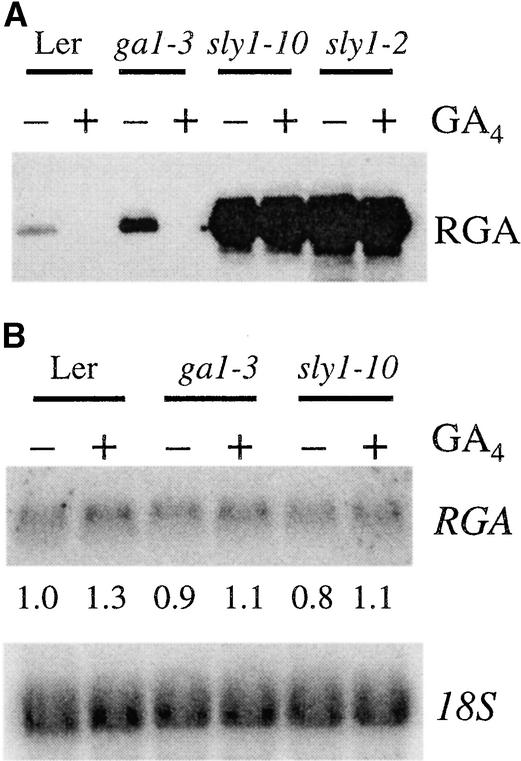

The fact that GA causes reduced accumulation of RGA (Silverstone et al., 2001) prompted the question, Is RGA a target of SCFSLY1 ubiquitin ligase? To explore this hypothesis, we examined the stability of RGA in sly1-2 and sly1-10. RGA accumulates at a much higher level in both sly alleles than in the wild type, even after GA treatment (Figure 6A). By contrast, the RGA mRNA level was not altered dramatically in the sly1-10 mutant (Figure 6B). These results show that SLY1 is directly or indirectly required for the GA-stimulated degradation of RGA. Given that SLY1 contains an F-box domain, we speculate that RGA may be a target of an SCFSLY1 complex.

Figure 6.

RGA Protein Levels, but Not the RGA mRNA, Are Highly Increased in sly1 Mutants.

(A) Eight-day-old seedlings were treated with (+) or without (−) 1 μM GA4 for 2 h, and protein extracts were fractionated by 8% SDS-PAGE. The protein blot was probed with an anti-RGA antibody. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal loading of the blot (data not shown).

(B) A duplicate RNA gel blot (described in Figure 1A) was hybridized with a labeled RGA DNA probe. Numerals below the blot indicate the relative levels of RGA mRNA after standardization using 18S as a loading control. The level of RGA mRNA in the water-treated wild type was arbitrarily set to 1.0.

Analysis of the sly1-10 rga-24 Double Mutant

If the dwarf phenotype of sly1 mutants is attributable to the overaccumulation of RGA, we would expect loss-of-function mutations in the RGA gene to rescue the sly1 dwarf phenotype. The sly1-10 allele was crossed to rga-24 and used to generate a sly1-10 rga-24 double mutant. Figure 3C shows a comparison of sly1-10, the sly1-10 rga-24 double mutant, and Ler after 60 days of growth on soil. The phenotype of the rga-24 mutant was almost identical to that of Ler (Silverstone et al., 1997). The rga-24 mutation clearly resulted in a partial rescue of the sly1-10 dwarf phenotype but did not significantly suppress the germination or fertility defects of sly1-10. This result indicates that rga-24 is epistatic to sly1-10 for stem elongation and that RGA acts downstream of SLY1 in GA signal transduction.

DISCUSSION

We report the map-based cloning of the SLY1 gene of Arabidopsis. SLY1 is a positive regulator of GA response. Recessive mutations in SLY1 affect the full range of GA phenotypes, including feedback regulation of the GA3ox1 biosynthetic gene (Figure 1). Thus, the fact that SLY1 encodes a putative F-box protein suggests that the GA signal is transmitted via an SCFSLY1 E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Ubiquitylation controls target protein activity at multiple levels, including proteolysis and the potentiation of transcriptional activation domains (Conaway et al., 2002). Major members of the SCF complex include homologs of SKP1, cullin, and the RING-finger domain protein Rbx1 (Zheng et al., 2002). The F-box subunit directs the interaction of the complex with a specific target for ubiquitylation. The conserved F-box domain allows the protein to interact with the SKP1 subunit of the SCF. SKP1 tethers the F-box protein to the N terminus of cullin. The RING-finger protein Rbx1 binds the C terminus of cullin and the E2 ubiquitin–conjugating enzyme. The E3 ubiquitin ligase catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the substrate. The formation of a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate targets it for proteolysis by the 26S proteasome.

In Arabidopsis, there are at least 21 Skp1 homologs (ASK [Arabidopsis Skp1]), 11 cullin homologs, and 2 Rbx homologs (Farras et al., 2001; Lechner et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2002). Recent work has characterized the superfamily of 694 putative F-box protein genes in Arabidopsis (Gagne et al., 2002; Kuroda et al., 2002). According to Gagne et al. (2002), the SLY1 gene falls into the C2 family of F-box proteins. Representatives of the Arabidopsis F-box family, including C2, were found to interact with Arabidopsis SKP1 homologs using yeast two-hybrid assays, indicating that they are part of functional SCF complexes. A representative of the C2 F-box family was shown to interact with ASK1, ASK2, ASK4, ASK11, and ASK13 (Gagne et al., 2002). SCF complexes in Arabidopsis may be regulated by self-ubiquitylation of the F-box or by RUB modification of the cullin subunit (Conaway et al., 2002; del Pozo et al., 2002). It was shown recently that RUB1 modification of AtCUL1 is required for normal auxin signal transduction. However, the precise role of RUB modification is unknown.

A number of previously published reports support the notion that the GA signal is transmitted by ubiquitylation and proteolysis. Reynolds and Hooley (1992) reported the isolation of a GA-regulated tetraubiquitin cDNA from Avena fatua. It is possible that an increased pool of ubiquitin is needed for GA response. Chen et al. (1995) identified a GA-induced cDNA that encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme in rice. Finally, the negative regulator of GA response, RGA, appears to be subject to GA-stimulated proteolysis (Silverstone et al., 2001). The barley and rice homologs of RGA, SLN1 and SLR1, respectively, also appear to be subject to GA-stimulated proteolysis (Chandler et al., 2002; Gubler et al., 2002; Itoh et al., 2002). This result suggests that this aspect of GA signal transduction is conserved among dicots and monocots. Recently, inhibitor studies suggested that the GA-stimulated proteolysis of barley SLN1 was dependent on the 26S proteasome, suggesting a role for the 26S proteosome in the GA-induced proteolysis of the RGA/SLN1/SLR1 family (Fu et al., 2002).

We propose that GA causes the ubiquitylation of RGA via an SCFSLY1 E3 ubiquitin ligase. According to this hypothesis, SLY1 acts positively in the GA response because it is the negative regulator of RGA, which is a negative regulator of the GA response. Evidence in favor of this model include the following: (1) sly1 mutants have a GA-insensitive phenotype; (2) the predicted SLY1 protein is homologous with an F-box; (3) RGA accumulates at high levels in sly1 mutants even in the presence of GA; and (4) the rga-24 mutation suppresses the dwarf phenotype of sly1-10. Figure 6 shows that mutations in SLY1 result in the high-level accumulation of RGA. Although this evidence does not directly prove an interaction between SLY1 and RGA, it is highly suggestive that an SCFSLY1 complex may direct the GA-stimulated degradation of RGA. If this hypothesis is correct, SLY1 will be the second F-box protein in plants for which a target has been identified. It is possible that the DELLA motif of RGA is needed for regulation by SCFSLY1, because this motif is essential for the GA-induced degradation of RGA (Dill et al., 2001). Like the sly1-10 mutation, deletion of the DELLA motif stabilizes RGA even in the presence of GA (Dill et al., 2001).

It is tempting to speculate that an SCFSLY1 complex might target the entire DELLA family, including GAI, RGL1, RGL2, and RGL3, for destruction. However, RGL2 appears to be regulated in transcription (Lee et al., 2002), and it was shown that RGL1-GFP (green fluorescent protein) and GAI-GFP translational fusion proteins are not subject to GA-regulated proteolysis (Fleck and Harberd, 2002; Wen and Chang, 2002). Although this work has not yet been confirmed by examination of native RGL1 and GAI proteins, it suggests that RGL1 and GAI are not subject to regulation by classic ubiquitin-directed proteolysis. Nevertheless, the sly1 mutants are defective in the full range of GA responses, whereas RGA affects stem elongation, leaf expansion, and flowering time. Thus, the sly1 phenotypes of increased seed dormancy and reduced fertility likely result from a mechanism other than increased levels of RGA protein. It will be important to determine if SLY1 regulates other GA response genes, including other members of the DELLA family.

sly1 mutant phenotypes are not as strong as those of the GA biosynthetic mutant ga1-3. The ga1-3 seeds have an absolute requirement for added GA to germinate. Although sly1 mutants show increased seed dormancy (5% germinate; Figure 2), they do eventually afterripen and hence germinate (C. Steber, unpublished data). The ga1-3 mutant has a stronger dwarf phenotype than sly1 mutants (Steber et al., 1998). Whereas ga1-3 plants are fully infertile, sly1 mutants are partially infertile. One possible explanation for this difference may be that the SLY1 homolog MIF21.6 may be functionally redundant with SLY1. This fact also may explain why GA can cause some reduction in GA3ox1 transcript levels in the sly1 mutant background. By contrast, GA cannot cause the reduction of RGA protein levels in a sly1 mutant background. This finding suggests that SLY1 is involved more directly in the regulation of RGA than in the regulation of GA3ox1.

Although the sly1 dwarf phenotype is not as strong as that of ga1-3, the sly1 mutants result in a considerably higher (approximately fivefold) level of RGA protein accumulation than ga1-3 (Figure 6). If plant height were a direct function of RGA protein levels, we would expect sly1 plants to be smaller than ga1-3 plants. There are two possible explanations for this finding. One is that the plant may compensate for RGA overabundance in sly1 mutants by downregulating other DELLA family proteins. Another is that the RGA protein that accumulates in sly1 mutants may not be fully functional.

How does GA control the activity of SCFSLY1? Most SCF ubiquitin ligase–regulated proteins are targeted for ubiquitylation and degradation by phosphorylation (Willems et al., 1999). However, there are examples of ubiquitin ligase–regulated proteins being targeted for ubiquitylation and destruction by Pro hydroxylation or by glycosylation (Huang et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2002). Phosphorylation was implicated recently in the regulation of the 26S proteosome–mediated proteolysis of the barley DELLA protein SLN1 (Fu et al., 2002). In addition, Sasaki et al. (2003) report evidence that the RGA homolog SLR1 is targeted for degradation by phosphorylation. Given that proteolysis is a conserved mechanism for regulating the DELLA family of proteins in plants, it is reasonable to speculate that RGA also may be regulated by phosphorylation. However, at present, there is no direct evidence of this phenomenon. In this model, SCFSLY1 would recognize RGA only when it is phosphorylated by a GA-stimulated kinase. Thus, a GA-regulated kinase and/or phosphatase may play a crucial role in GA signaling.

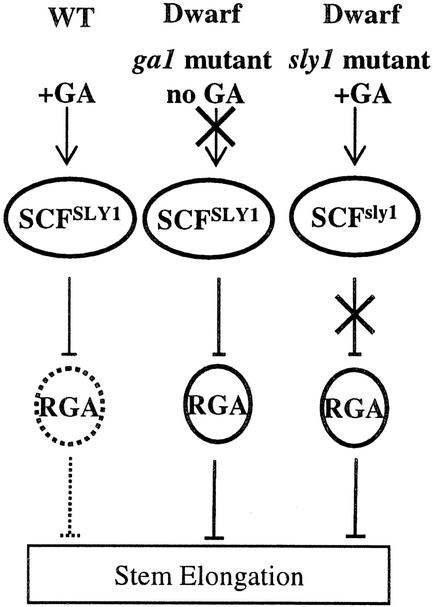

In summary, we propose a model for the role of SLY1 in GA signal transduction (Figure 7). Wild-type plants (+GA) reach normal height because GA stimulates SCFSLY1 to target RGA for degradation, thus alleviating the RGA inhibition of stem elongation. In GA biosynthetic mutants (no GA), there is insufficient GA to stimulate the SCFSLY1 complex to target RGA for proteolysis. The overabundance of RGA inhibits stem elongation, leading to a dwarf phenotype. Mutations in SLY1 prevent the degradation of RGA in both the presence and absence of GA, leading to RGA inhibition of stem elongation and a dwarf phenotype.

Figure 7.

Model for the Role of SLY1 in GA Signaling.

The dwarf phenotype of GA biosynthetic mutants results from the accumulation of active RGA protein. In wild-type (WT) plants (+GA), GA stimulates SCFSLY1 (directly or indirectly) to target RGA for degradation, resulting in normal height. The ga1 biosynthetic mutant is a dwarf because there is insufficient GA to stimulate SCFSLY1 to target RGA for proteolysis. The sly1 mutant is a dwarf because a lack of functional SCFSLY1 results in increased accumulation of RGA.

METHODS

Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Landsberg erecta and Columbia and BAC clones used in this study were obtained from the ABRC (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). Plants were grown under a regimen of 16-h days at 22°C and 8-h nights at 16°C under halide lights at 100 to 150 μE·m−2·s−1. sly1 mutants are less fertile if grown under continuous light. Before plating on 0.5× Murashige and Skoog (1962) basal salt mixture (Sigma) plus 0.8% (g/v) agar, seeds were surface-sterilized by incubation in 10% (v/v) bleach and 0.01% SDS for 10 min followed by six washes in sterile water. Seeds were allowed to imbibe for 4 days at 4°C to ensure synchronous germination and then moved to continuous fluorescent light at 50 μE·m−2·s−1 and 22°C. Seeds with emerging radicals were scored as germinated after 7 days under lights. Stock solutions of GA4 (Sigma or a gift from Tadao Asami, RIKEN, Saitama, Japan) were made in ethanol. Plant hormones were added to autoclaved medium cooled to 55°C.

For the analysis of RGA protein levels and expression of RGA and GA3ox1 transcripts, Arabidopsis seedlings were grown as described previously (Silverstone et al., 2001). To facilitate germination, ga1-3 seeds were pretreated with 100 μM GA4 during the stratification period and then washed five times with water. Treatments with GA4 or water were performed by adding 1 mL of solution directly to the surface of the agar. Whole seedlings were harvested and ground directly in liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar.

Map-Based Cloning

Simple sequence length polymorphism and cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) markers were used to localize SLY1 to chromosome IV (Konieczny and Ausubel, 1993; Bell and Ecker, 1994). CAPS markers used to fine map the SLY1 gene are listed in the supplemental data online. Clones marked “cereon” were based on the Cereon markers at the TAIR World Wide Web site (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). All other markers were derived in this study. The germination and dwarf phenotypes of the sly1 mutant necessitated using PCR-based mapping markers. Nineteen new CAPS markers were defined by screening 56 2-kb PCR products using 4-bp cutters (see supplemental data online). To identify the SLY1 gene by complementation, sublibraries were generated from BAC clones T19F6 and T22A6 by partial digestion with Sau3AI. Inserts ranging from 5 to 20 kb were inserted into the BamHI cloning site in pBIN19. Subclones representing the region were transformed into sly1-2 or sly1-10 (Bechtold et al., 1993; Clough and Bent, 1998). Sequence alignments were determined using tBLASTn to search the TIGR EST and GenBank databases (Altschul et al., 1990; Smith et al., 1996; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, 2002; www.tigr.org,2002).

The SLY1 Transcript

The SLY1 cDNA 3′ end was determined by sequencing the 3′ ends of full-length cDNAs recovered from an Arabidopsis Columbia uni-Zap XR cDNA library (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to identify a polyadenylated sequence. The 3′ end was amplified (2 μL of cDNA library, 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM primer, 1× reaction buffer, and 5 units of Ex-Taq polymerase [Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan] for 40 cycles of 96°C for 25 s, 60°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 80 s) using sly1-2f (5′-AGACGAGCGGCTTTGGGAGC-3′) for five cycles before the addition of T7 primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′). This PCR product was used as a template for the reaction using 2-63f (5′-TCTCTCTAAACC-CAATCCG-3′) for five cycles before the addition of T7 primer. PCR products were gel purified (Qiaex II; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cloned using the TOPO-XL PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Clones were sequenced using fluorescence-based dideoxy terminators and Ampli-Taq polymerase and run on an Applied Biosystems sequencer (model 377; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, CT).

Because of the presence of the MIF21.6 SLY1 homolog on chromosome V, it was difficult to specifically detect the SLY1 transcript by RNA gel blot analysis. Thus, qualitative reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR was used to search for the presence or absence of SLY1 mRNA in various aerial tissues and in sly1 mutants. Tissue was harvested from 8-week-old Arabidopsis plants or from seedlings (where indicated). Total RNA was extracted from 0.1 g of plant tissue using the RNeasy Plant Mini Prep Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with the addition of an RNase-free DNaseI treatment (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Reverse transcriptase–mediated PCR was conducted on 100 ng of total RNA using a Roche LightCycler and the LightCycler RNA Amplification Kit SYBR Green I (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions at an annealing temperature of 56°C with 5 mM MgCl2. A no–reverse transcription control was included for all RNA preparations to confirm the absence of genomic DNA contamination. The primers used for SLY1 amplification were 5′-TCTCTCTAAACCCAATCCG-3′ and 5′-CCAGCATTGAACATCACATCTGAC-3′. The primers used for ACT2 amplification were 5′-CTGGATTCTGGTGATGGTGTGTC-3′ and 5′-TCT-TTGCTCATACGGTCAGCG-3′ (An et al., 1996). The products of amplification were separated on a 2% agarose gel for 3 h at 60 V (Sambrook et al., 1989).

Immunoblot Analysis

Total protein was extracted from water- or GA4-treated seedlings as described previously (Silverstone et al., 2001). For each sample, 20 μg of total protein was fractionated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and examined by immunoblot analysis (Silverstone et al., 2001) using a 2000-fold dilution of an anti-RGA antibody from rat and a 7500-fold dilution of peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rat IgG. Immunoreactive species on the blots were detected using Supersignal Dura Reagent (Pierce). Ponceau staining was performed by incubating the blot with 0.2% (w/v) Ponceau S (Sigma) in 1% (v/v) acetic acid.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of GA3ox1 and RGA Transcripts

Total RNA was isolated and GA3ox1 mRNA was detected using an antisense GA3ox1 RNA probe as described previously (Yamaguchi et al., 1998). The RGA transcripts were analyzed using a random primed labeled 2.3-kb RGA DNA probe as described (Silverstone et al., 1998). As a loading control, blots were reprobed with a labeled 18S oligonucleotide probe as described previously (Dill and Sun, 2001). The RNA blots were exposed to a Storage Phosphor Screen (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA) and quantified with a PhosphorImager (model 455Si; Molecular Dynamics) using Imagequant version 5.1 software.

Generation of the sly1-10 rga-24 Mutant

We isolated the sly1-10 rga-24 homozygous double mutant by crossing rga-24 and sly1-10. The genotypes of homozygous F2 plants were confirmed using allele-specific PCR primers. Genotyping of the rga-24 allele was performed as described previously (Dill and Sun, 2001). Primers sly1-10f (5′-TCGTCACTGGACTAACATCGGCTG-3′) and 2-63r (5′-GCT-AACAGTCTGGCTTATGGATAC-3′) were used to amplify a 350-bp product in SLY1 but not sly1-10. Primers sly1-10f and sly1-10r2 (5′-GAGCATGCTTGATCCTAGGA-3′) were used to amplify a 320-bp product in sly1-10 but not in SLY1. PCR was performed as described (Dill and Sun, 2001).

Upon request, all novel materials described in this article will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank accession number for the SLY1 gene is NM_118554. Other accession numbers are as follows: Arabidopsis TIR1, AF327430; SLY1 plant homologs from soybean, BI785351; Medicago truncatula, BQ239225; Arabidopsis MIF21.6, AB023039; rice OsGID2, AB100246; and barley, BF622212.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Fjeld, J. Sibert, K. Smiley, and J. Allemandi for expert technical assistance. We thank P. McCourt for helpful discussions. We thank M. Matsuoka for sharing data before publication. This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Grant 99-01809 to C.M.S. and by National Science Foundation Grant IBN-0078003 to T.-p.S.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.010827.

References

- Allan, R.E. (1986). Agronomic comparison among wheat lines nearly isogenic for three reduced-height genes. Crop Sci. 26, 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.Q., McDowell, J.M., Huang, S., McKinney, E.C., Chambliss, S., and Meagher, R.B. (1996). Strong, constitutive expression of the Arabidopsis ACT2/ACT8 actin subclass in vegetative tissues. Plant J. 10, 107–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold, N., Ellis, J., and Pelletier, G. (1993). In planta Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 316, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.J., and Ecker, J.R. (1994). Assignment of 30 microsatellite loci to the linkage map of Arabidopsis. Genomics 19, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent, A.F., Kunkel, B.N., Dahlbeck, D., Brown, K.L., Schmidt, R., Giraudat, J., Leung, J., and Staskawicz, B.J. (1994). RPS2 of Arabidopsis thaliana: A leucine-rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Science 265, 1856–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarelli, C., Chiaur, D.S., Guardavaccaro, D., Parks, W., Vidal, M., and Pagano, M. (1999). Identification of a family of human F-box proteins. Curr. Biol. 9, 1177–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, P.M., Marion-Poll, A., Ellis, M., and Gubler, F. (2002). Mutants at the Slender1 locus of barley cv Himalaya: Molecular and physiological characterization. Plant Physiol. 129, 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X., Wang, B., and Wu, R. (1995). A gibberellin-stimulated ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene involved in α-amylase gene expression in rice aleurone. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, H.H., Hwang, I., and Goodman, H.M. (1995). Isolation of the Arabidopsis GA4 locus. Plant Cell 7, 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway, R.C., Brower, C.S., and Conaway, J.W. (2002). Emerging roles of ubiquitin in transcription regulation. Science 296, 1254–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling, R.J., Kamiya, Y., Seto, H., and Harberd, N.P. (1998). Gibberellin dose–response regulation of GA4 gene transcript levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 117, 1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker, C.J., and Parker, R. (1995). Diversity of cytoplasmic functions for the 3′ untranslated region of eukaryotic transcripts. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 7, 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo, J.C., Dharmasiri, S., Hellmann, H., Walker, L., Gray, W.M., and Estelle, M. (2002). AXR1-ECR1–dependent conjugation of RUB1 to the Arabidopsis cullin AtCUL1 is required for auxin response. Plant Cell 14, 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo, J.C., and Estelle, M. (2000). F-box proteins and protein degradation: An emerging theme in cellular regulation. Plant Mol. Biol. 44, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill, A., Jung, H.S., and Sun, T.P. (2001). The DELLA motif is essential for gibberellin-induced degradation of RGA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14162–14167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill, A., and Sun, T. (2001). Synergistic derepression of gibberellin signaling by removing RGA and GAI function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 159, 777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farras, R., Ferrando, A., Jasik, J., Kleinow, T., Okresz, L., Tiburcio, A., Salchert, K., del Pozo, C., Schell, J., and Koncz, C. (2001). SKP1-SnRK protein kinase interactions mediate proteasomal binding of a plant SCF ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 20, 2742–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, B., and Harberd, N.P. (2002). Evidence that the Arabidopsis nuclear gibberellin signalling protein GAI is not destabilised by gibberellin. Plant J. 32, 935–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg, I., Kuusk, S., Moritz, T., and Sundberg, E. (1999). The Arabidopsis dwarf mutant shi exhibits reduced gibberellin responses conferred by overexpression of a new putative zinc finger protein. Plant Cell 11, 1019–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg, I., Kuusk, S., Robertson, M., and Sundberg, E. (2001). The Arabidopsis protein SHI represses gibberellin responses in Arabidopsis and barley. Plant Physiol. 127, 937–948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X., Richards, D.E., Ait-Ali, T., Hynes, L.W., Ougham, H., Peng, J., and Harberd, N.P. (2002). Gibberellin-mediated proteasome-dependent degradation of the barley DELLA protein SLN1 repressor. Plant Cell 14, 3191–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, J.M., Downes, B.P., Shiu, S.H., Durski, A.M., and Vierstra, R.D. (2002). The F-box subunit of the SCF E3 complex is encoded by a diverse superfamily of genes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11519–11524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, W.M., Kepinski, S., Rouse, D., Leyser, O., and Estelle, M. (2001). Auxin regulates SCFTIR1-dependent degradation of AUX/IAA proteins. Nature 414, 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler, F., Chandler, P.M., White, R.G., Llewellyn, D.J., and Jacobsen, J.V. (2002). Gibberellin signaling in barley aleurone cells: Control of SLN1 and GAMYB expression. Plant Physiol. 129, 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden, P., and Phillips, A.L. (2000). Gibberellin metabolism: New insights revealed by the genes. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, H., and Estelle, M. (2002). Plant development: Regulation by protein degradation. Science 297, 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., Zhao, Q., Mooney, S.M., and Lee, F.S. (2002). Sequence determinants in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α for hydroxylation by the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39792–39800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyin, G.P., Rialland, M., Pigeon, C., and Guguen-Guillouzo, C. (2000). cDNA cloning and expression analysis of new members of the mammalian F-box protein family. Genomics 67, 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, H., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Sato, Y., Ashikari, M., and Matsuoka, M. (2002). The gibberellin signaling pathway is regulated by the appearance and disappearance of SLENDER RICE1 in nuclei. Plant Cell 14, 57–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.E., Binkowski, K.A., and Olszewski, N.E. (1996). SPINDLY, a tetratricopeptide repeat protein involved in gibberellin signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9292–9296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.E., and Olszewski, N.E. (1993). Mutations at the SPINDLY locus of Arabidopsis alter gibberellin signal transduction. Plant Cell 5, 887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S., and Delaney, T.P. (2002). Arabidopsis SON1 is an F-box protein that regulates a novel induced defense response independent of both salicylic acid and systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 14, 1469–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, K.E., Moritz, T., and Harberd, N.P. (2001). Gibberellins are not required for normal stem growth in Arabidopsis thaliana in the absence of GAI and RGA. Genetics 159, 767–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konieczny, A., and Ausubel, F.M. (1993). A procedure for mapping Arabidopsis mutations using co-dominant ecotype-specific PCR-based markers. Plant J. 4, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, H., Takahashi, N., Shimada, H., Seki, M., Shinozaki, K., and Matsui, M. (2002). Classification and expression analysis of Arabidopsis F-box-containing protein genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1073–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner, E., et al. (2002). The AtRbx1 protein is part of plant SCF complexes, and its down-regulation causes severe growth and developmental defects. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50069–50080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., Cheng, H., King, K.E., Wang, W., He, Y., Hussain, A., Lo, J., Harberd, N.P., and Peng, J. (2002). Gibberellin regulates Arabidopsis seed germination via RGL2, a GAI/RGA-like gene whose expression is up-regulated following imbibition. Genes Dev. 16, 646–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T., and Skoog, F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473.–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ogas, J., Kaufmann, S., Henderson, J., and Somerville, C. (1999). PICKLE is a CHD3 chromatin-remodeling factor that regulates the transition from embryonic to vegetative development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13839–13844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, N., Sun, T.P., and Gubler, F. (2002). Gibberellin signaling: Biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell 14 (suppl.), S61.–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., Carol, P., Richards, D.E., King, K.E., Cowling, R.J., Murphy, G.P., and Harberd, N.P. (1997). The Arabidopsis GAI gene defines a signaling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes Dev. 11, 3194–3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., and Harberd, N. (2002). The role of GA-mediated signalling in the control of seed germination. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., et al. (1999). “Green revolution” genes encode mutant gibberellin response modulators. Nature 400, 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, G.J., and Hooley, R. (1992). cDNA cloning of a tetraubiquitin gene, and expression of ubiquitin-containing transcripts, in aleurone layers of Avena fatua. Plant Mol. Biol. 20, 753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, D.E., King, K.E., Ait-Ali, T., and Harberd, N.P. (2001). How gibberellin regulates plant growth and development: A molecular genetic analysis of gibberellin signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 67–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E.F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

- Sanchez-Fernandez, R., Ardiles-Diaz, W., Van Montagu, M., Inza, D., and May, M.J. (1998). Cloning of a novel Arabidopsis thaliana RGA-like gene, a putative member of the VHIID-domain transcription factor family. J. Exp. Bot. 49, 1609–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, A., Itoh, H., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Ishiyama, K., Kobayashi, M., Jeong, D.-H., An, G., Kitano, H., Ashikari, M., and Matsuoka, M. (2003). A defect in a putative F-box gene causes accumulation of the phosphorylated repressor protein for GA signaling. Science 299, 1896–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R., West, J., Love, K., Lenehan, Z., Lister, C., Thompson, H., Bouchez, D., and Dean, C. (1995). Physical map and organization of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 4. Science 270, 480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.H., Parmentier, Y., Hellmann, H., Lechner, E., Dong, A., Masson, J., Granier, F., Lepiniec, L., Estelle, M., and Genschik, P. (2002). Null mutation of AtCUL1 causes arrest in early embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1916–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone, A.L., Ciampaglio, C.N., and Sun, T. (1998). The Arabidopsis RGA gene encodes a transcriptional regulator repressing the gibberellin signal transduction pathway. Plant Cell 10, 155–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone, A.L., Jung, H.S., Dill, A., Kawaide, H., Kamiya, Y., and Sun, T.-p. (2001). Repressing a repressor: Gibberellin-induced rapid reduction of the RGA protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13, 1555–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone, A.L., Mak, P.Y.A., Martinez, E.C., and Sun, T. (1997). The new RGA locus encodes a negative regulator of gibberellin response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 146, 1087–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.F., Wiese, B.A., Wojzynski, M.K., Davison, D.B., and Worley, K.C. (1996). BCM Search Launcher: An integrated interface to molecular biology data base search and analysis services available on the World Wide Web. Genome Res. 6, 454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steber, C.M., Cooney, S.E., and McCourt, P. (1998). Isolation of the GA-response mutant sly1 as a suppressor of ABI1-1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 149, 509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steber, C.M., and McCourt, P. (2001). A role for brassinosteroids in germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 125, 763–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain, S.M., Tseng, T.S., Thornton, T.M., Gopalraj, M., and Olszewski, N.E. (2002). SPINDLY is a nuclear-localized repressor of gibberellin signal transduction expressed throughout the plant. Plant Physiol. 129, 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.K., and Chang, C. (2002). Arabidopsis RGL1 encodes a negative regulator of gibberellin responses. Plant Cell 14, 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems, A.R., Goh, T., Taylor, L., Chernushevich, I., Shevchenko, A., and Tyers, M. (1999). SCF ubiquitin protein ligases and phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 354, 1533–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., Liu, F., Lechner, E., Genschik, P., Crosby, W.L., Ma, H., Peng, W., Huang, D., and Xie, D. (2002). The SCFCOI1 ubiquitin-ligase complexes are required for jasmonate response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14, 1919–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S., Smith, M.W., Brown, R.G., Kamiya, Y., and Sun, T. (1998). Phytochrome regulation and differential expression of gibberellin 3β-hydroxylase genes in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 10, 2115–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, Y., et al. (2002). E3 ubiquitin ligase that recognizes sugar chains. Nature 418, 438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Schaffer, A.A., Miller, W., Madden, T.L., Lipman, D.J., Koonin, E.V., and Altschul, S.F. (1998). Protein sequence similarity searches using patterns as seeds. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 3986–3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, N., et al. (2002). Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416, 703–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.