Abstract

Conformational properties of trimeric and tetrameric 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides, 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), and their 3′,5′-linked analogs, 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4), were examined with the use of heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. The temperature-dependent 3JHH, 3JHP and 3JCP coupling constants, acquired in the range of 273–343 K, gave insight into the conformation of sugar rings in terms of a two-state North ↔ South (N ↔ S) pseudorotational equilibrium and into the conformation of the sugar–phosphate backbone in the model antisense oligonucleotides 1–4. 2′,5′-linked oligomers 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) show preference for N-type conformers and indication of A-type conformational features, which is prerequisite for antisense hybridization. The drive of N ↔ S equilibrium in 1–4 has been rationalized with the competing gauche effects of 2′/3′-phosphodiester and 3′/2′-MOE groups, anomeric and steric effects. Furthermore, the pairwise comparisons of 3′-MOE with 3′-OH and 3′-deoxy 2′,5′-linked adenine trimers emphasized the fine tuning of N ↔ S equilibrium in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) by the steric effects of 3′-MOE group and the possibility of water-mediated H-bonds with vicinal phosphodiester functionality. In full correspondence, the drive of N ↔ S equilibrium towards N by 2′-MOE in 3′,5′-linked analogs 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) is weaker in comparison with 3′-OH group in the corresponding ribo analogs. βt, γ+ and ε– rotamers are preferred in both 2′,5′- and in 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides 1–4.

INTRODUCTION

The success of DNA phosphorothioates as antisense agents has stimulated a wide variety of chemical modifications in the phosphate backbone, pentofuranosyl moieties and nucleo base fragments of nucleic acids (1–4). An ideal antisense oligonucleotide is expected to favorably hybridize with RNA, exhibit cell permeability and resistance to enzymatic degradation as well as induce cleavage of the hybrid duplex by nucleases such as RNase H. All these requirements are difficult to combine in a single construct that is a candidate for potential gene-targeting applications. The second generation of antisense oligonucleotides involves the modification of a 2′-OH group with other electronegative groups that favor N-type sugar conformation through the gauche effect of [O4′-C1′-C2′-X2′] fragments (2,3). Recently, the locked nucleic acids have been introduced in which the 2′-O,4′-C-methylene bridge locks the nucleotide in a C3′-endo (N-type) conformation (5–7). The preference for N-type sugar conformation improves binding affinity (8–10). In addition, carbohydrate modifications at the 2′-position of RNA mimic increase nuclease resistance, chemical stability against depurination and alter the lipophilicity, all of which contribute to improved pharmacokinetic properties (11). For example, 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl)-RNA [(2′-MOE)-RNA] oligonucleotides exhibit C3′-endo sugar conformation, stand out in their binding affinities to target RNAs and show good nuclease resistance (4).

Comprehensive analyses of a two-state North (N, roughly C3′-endo) ↔ South (S, roughly C2′-endo) pseudorotational equilibrium in nucleosides and nucleotides have shown that the sugar conformation is controlled by the gauche effects of [O4′-C-C-O3′/2′] fragments, anomeric effect of the heterocyclic nucleobase and steric interactions (12–17). The quantitative thermodynamic data on N ↔ S equilibrium has proved itself in the design of modifications that lead to the desired engineered major conformers of pentofuranosyl moieties, which subsequently drive sugar–phosphate backbone conformation. The more a nucleoside building block is preorganized in an N-type furanose conformation, the higher the stability of the duplex between the modified oligomer and its RNA complement (2,3). A recent NMR study has shown that DNA with 2′,5′-phosphodiester bonds forms an A-type duplex in solution (18).

In the present study we have focused on the backbone-modified 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides (19) that have recently shown modulation of immunostimulatory properties (20). It has already been shown that antisense applications of 2′-MOE-substituted RNA oligonucleotides, with 3′,5′-linked backbones, exhibit improved nuclease resistance, higher RNA affinity, reduced toxicity and better cellular uptake in comparison with their 2′-OH analogs (4). Here we have prepared 2′,5′-linked adenosine oligonucleotides with 3′-MOE modification 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) (Scheme 1). The conformational properties of 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) (Scheme 1) were assessed in aqueous solution with the use of heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy and compared to their 3′,5′-linked analogs, trimer 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and tetramer 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (4).

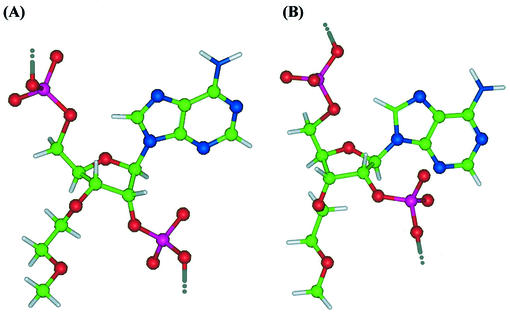

Scheme 1. (A) Non-terminal monomer building block of 2′,5′-linked trinucleoside diphosphate 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and tetranucleoside triphosphate 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2). (B) Non-terminal monomer building block of 3′,5′-linked trinucleoside diphosphate 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and tetranucleoside triphosphate 2′-MOE- A43′,5′ (4).

Our results show that the substitution of 3′-OH group in 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides by 3′-MOE, as found in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), leads to increased populations of N-type conformers that, in addition to all the advantages of 2′-MOE modification in natural 3′,5′-linked analogs, results in conformational preorganization that offers favorable hybridization properties. In contrast, the analysis of temperature-dependent NMR data shows that 2′-MOE modification in natural 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides, 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4), leads to preferential stabilization of S-type conformers in comparison to parent ribo oligomers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NMR measurements

NMR spectra were recorded on Varian Unity Inova 600 NMR spectrometer at the Slovenian NMR Center at 600.07 MHz for 1H nuclei, 150.91 MHz for 13C and 242.91 MHz for 31P nuclei. Spectra were acquired in D2O (99.9% deuterium), 10 mM Na-phosphate buffer at neutral pH (pH* = 6.9) and 18 mM 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), 14 mM 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), 13 mM 2′-MOE-A42′,5′ (3) and 11 mM 2′-MOE-A42′,5′ (4). The pH* values were measured by a combined glass electrode calibrated with standard buffers with a pH of 4, 7 and 10 in H2O and were not corrected for the deuterium isotope effect. Tetramethyl ammonium chloride was used as internal reference for 1H NMR (δ = 3.185 p.p.m.) spectra. 3JH1′H2′, 3JH2′H3′, 3JH3′H4′ and 3JH2′P coupling constants were measured from 1D 1H proton spectra, whereas 3JH4′H5′, 3JH4′H5′′, 3JH5′P and 3JH5′′P coupling constants were obtained from DQF-COSY spectra and JCP coupling constants from HSQC spectra. The errors in coupling constants were: ±0.1 Hz for JHH, ±0.2 Hz for JHP and ±0.4 Hz for JCP and JH5′/5′′P. The sample temperature was varied from 273 to 343 K and controlled to approximately ±0.1 K.

1D 1H measurements were performed under the following spectral and processing conditions: 5.4 kHz sweep width, 32 K time domain, zero filling to 128 K and slight Gaussian apodization to give enhanced resolution. JCP coupling constants were obtained with the use of extensively folded HSQC experiments (21) using gradients for coherence selection; 4096 (ω2) × 2048 (ω1) data points, 16 scans per FID, 16 dummy scans, appropriate delays were calculated according to 1JCH = 140 Hz, 5.4 kHz (ω2) × 2.4 kHz (ω1) spectral width, transformed after multiplication with a sine-bell squared filter shifted by π/2 in both ω2 and ω1 to give 8 × 16 K matrix. DQF-COSY experiments were acquired with 4096 (ω2) × 1024 (ω1) data points, 16 scans per FID, transformed after multiplication with a sine-bell squared filter shifted by π/2 in both ω2 and ω1 to give 8 × 2 K matrix. NOESY experiments were acquired with 4096 (ω2) × 256 (ω1) data points, eight scans per FID, with mixing times from 100 to 400 ms. Digital resolutions were 0.05 Hz in 1H 1D spectra, 0.2 Hz along 1H (f2) axis of DQF-COSY spectra and 0.3 Hz along 13C (f1) axis of HSQC spectra.

Conformational analysis

The conformational analysis of sugar moiety has been performed with the computer program PSEUROT (22,23) with the use of λ electronegativities (24) for the substituents along H-C-C-H fragments and the six-parameter generalized Karplus–Altona equation (25). The following λ electronegativity values were used: 0.0 for H, 0.58 for heterocyclic base, 1.26 for OH, 1.25 for phosphate group, 0.62 for C1′, C2′, C3′ and C4′, 1.27 for O4′ and 0.68 for C5′. In the optimization procedure the geometries and populations of both N- and S-type pseudorotamers were varied to obtain the best fit between the experimental and the calculated coupling constants. Our optimization procedure started with the following values: PN = 18°, ΨmN = 36°, PS = 162° and ΨmS = 36°. The puckering amplitude and phase angle of the minor S-type conformer was kept frozen during the individual iterative least-squares optimization, whereas parameters for the minor N-type were freely optimized and vice versa. The optimization resulted in the following ranges of P and Ψm for the N- and S-type geometries in all residues which best agreed with the experimental 3JHH coupling constant data: –7° < PN < 19°, 146° < PS < 158°, 34° < ΨmN = ΨmS < 36°, r.m.s. < 0.15 Hz, ΔJmax < 0.23 Hz for individual residues in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), –13° < PN < 16°, 140° < PS < 160°, 31° < ΨmN = ΨmS < 38°, r.m.s. < 0.15 Hz, ΔJmax < 0.34 Hz for individual residues in 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), –15° < PN < 32°, 134° < PS < 182°, 33° < ΨmN = ΨmS < 39°, r.m.s. < 0.15 Hz, ΔJmax < 0.32 Hz for individual residues in 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3). For 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) we were able to measure only 3JH1′H2′ coupling constants and thus geometries obtained for 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) were used in conformational analysis of individual residues in 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4), whereas populations of individual conformers were optimized.

MD simulation

MD simulation of 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) was performed with Insight II (v. 2000.1) software package (Accelrys) employing the AMBER force field. Distance-dependent dielectric constant value of 4 was used and Coulombic interactions have been reduced to 0.1. Starting geometry of 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) was energy minimized and MD simulation was started. Simulation was performed for 3 ns at 600 K after a few preliminary short MD simulations at various temperatures from 300 to 1000 K.

RESULTS

The conformational equilibria of trimers 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3), and tetramers 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) in aqueous solution were evaluated with the use of 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR chemical shifts were measured at 11 temperatures between 273 and 343 K (see Table 1 for data at the lowest and the highest temperatures). All proton resonances of sugar and nucleobase protons in model oligonucleotides 1–4 have been completely assigned with the use of NOESY experiments, selective 1D TOCSY and 2D DQF-COSY, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC experiments. The 2′/3′- and 5′-terminal residues in 1–4 were easily identified due to the absence of scalar coupling of respective protons with phosphorous atoms. The temperature-dependent vicinal 3JHH, 3JHP and 3JCP coupling constants (Table 2), and NOE enhancements reflected time-averaged values of several rapidly interconverting conformers in aqueous solution.

Table 1. 1H NMR chemical shifts for 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) at two limiting temperaturesa.

| Compound | Residue | T(K) | H8 | H2 | H1′ | H2′ | H3′ | H4′b | H5′b | H5′′b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A1 | 273 | 8.020 | 7.682 | 5.999 | 5.169 | 4.355 | 4.227 | 3.736 | 3.593 |

| 343 | 8.110 | 7.937 | 6.084 | 5.162 | 4.313 | 4.260 | 3.786 | 3.658 | ||

| A2 | 273 | 7.971 | 7.776 | 5.949 | 4.961 | 4.463 | 4.193 | 4.057 | 3.912 | |

| 343 | 8.067 | 8.026 | 6.010 | 5.073 | 4.315 | 4.145 | 3.951 | 3.798 | ||

| A3 | 273 | 7.908 | 8.105 | 5.836 | 4.474 | 4.158 | 4.298 | 4.161 | 4.056 | |

| 343 | 8.093 | 8.235 | 5.905 | 4.522 | 4.096 | 4.226 | 4.047 | 4.003 | ||

| 2 | A1 | 273 | 8.031 | 7.691 | 6.019 | 5.211 | 4.391 | 4.219 | 3.718 | 3.587 |

| 343 | 8.086 | 7.937 | 6.078 | 5.162 | 4.313 | 4.251 | 3.781 | 3.655 | ||

| A2 | 273 | 7.852 | 7.826 | 5.851 | 4.685 | 4.272 | 4.127 | 3.997 | 3.937 | |

| 343 | 7.984 | 8.008 | 5.945 | 4.927 | 4.220 | 4.081 | 3.905 | 3.798 | ||

| A3 | 273 | 7.880 | 7.779 | 5.875 | 5.102 | 4.464 | 4.231 | 4.112 | 4.031 | |

| 343 | 8.036 | 8.022 | 5.989 | 5.113 | 4.331 | 4.195 | 4.003 | 3.952 | ||

| A4 | 273 | 7.892 | 8.110 | 5.825 | 4.401 | 4.135 | 4.143 | c | 4.054 | |

| 343 | 8.077 | 8.228 | 5.895 | 4.500 | 4.081 | 4.098 | c | 3.993 | ||

| 3 | A1 | 275 | 8.210 | 7.917 | 5.924 | 4.586 | 4.760 | 4.384 | 3.867 | 3.828 |

| 323 | 8.228 | 8.127 | 5.954 | 4.587 | 4.789 | 4.376 | 3.812 | 3.783 | ||

| A2 | 275 | 8.237 | 8.082 | 5.946 | 4.472 | 4.830 | 4.536 | 4.256 | 4.198 | |

| 323 | 8.343 | 8.182 | 6.036 | 4.601 | 4.889 | 4.534 | 4.188 | 4.188 | ||

| A3 | 275 | 8.253 | 7.979 | 6.046 | 4.351 | 4.550 | 4.359 | 4.279 | 4.192 | |

| 323 | 8.375 | 8.145 | 6.119 | 4.505 | 4.532 | 4.378 | 4.243 | 4.203 | ||

| 4 | A1 | 275 | 8.201 | 7.902 | 5.913 | 4.583 | 4.736 | 4.385 | 3.864 | 3.828 |

| 323 | 8.223 | 8.124 | 5.947 | 4.583 | 4.784 | 4.373 | 3.799 | 3.799 | ||

| A2 | 275 | 8.178 | 7.856 | 5.850 | 4.338 | 4.746 | 4.511 | 4.294 | 4.232 | |

| 323 | 8.303 | 8.077 | 5.970 | 4.562 | 4.860 | 4.529 | 4.219 | 4.219 | ||

| A3 | 275 | 8.122 | 7.879 | 5.866 | 4.508 | 4.806 | 4.537 | 4.244 | 4.192 | |

| 323 | 8.313 | 8.082 | 6.013 | 4.529 | 4.861 | 4.519 | 4.175 | 4.175 | ||

| A4 | 275 | 8.204 | 8.108 | 6.030 | 4.284 | 4.533 | 4.385 | 4.275 | 4.167 | |

| 323 | 8.372 | 8.197 | 6.115 | 4.520 | 4.594 | 4.381 | 4.240 | 4.202 |

aChemical shifts are in p.p.m. (±0.001 p.p.m.).

bChemical shifts for H4′, H5′ and H5′′ resonances in 1–4 have been extracted from DQF-COSY spectra and are for 1 and 2 reported at 275 and 323 K. All other chemical shifts for 1 and 2 are reported at 273 and 343 K.

cH5′ resonance in residue A4 in 2 could not be extracted due to the overlap with CH2 protons.

Table 2. JHH, JHP and JCP coupling constants in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) and 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) at 275 and 323 Ka.

| JHH | JHP | JCP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residue | T | 1′2′ | 2′3′ | 3′4′ | 4′5′ | 4′5′′ | 2′P | 5′P | 5′′P | 1′P2′ | 3′P2′ | 4′P5′ | |

| 1 | A1 | 275 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 8.9 | - | - | 3.7 | 3.3 | - |

| 323 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 9.0 | - | - | 5.9 | 3.3 | - | ||

| A2 | 275 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 9.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 6.6 | 2.3 | 9.2 | |

| 323 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 9.4 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 9.6 | ||

| A3 | 275 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.9 | b | 3.7 | - | b | 2.6 | - | - | 9.2 | |

| 323 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 3.8c | 3.7c | - | b | b | - | - | 9.2 | ||

| 2 | A1 | 275 | 3.5 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 9.2 | - | - | 4.4 | 4.4 | - |

| 323 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 9.0 | - | - | 5.9 | 4.1 | - | ||

| A2 | 275 | 2.0 | 4.4 | b | 3.4 | 4.6 | 9.3 | 4.9 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 7.6 | |

| 323 | 3.1 | 5.0 | b | 3.8 | 4.3 | 8.9 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 7.9 | ||

| A3 | 275 | 3.2 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 9.5 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 7.9 | |

| 323 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 9.3 | b | b | 5.6 | 3.5 | 9.1 | ||

| A4 | 275 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 5.5 | b | 3.6 | - | b | 3.3 | - | - | 10.6 | |

| 323 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 3.8 | - | b | b | - | - | 9.1 | ||

| Residue | T | 1′2′ | 2′3′ | 3′4′ | 4′5′ | 4′5′′ | 3′P | 5′P | 5′′P | 2′P3′ | 4′P3′ | 4′P5′ | |

| | |||||||||||||

| 3 | A1 | 275 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 8.3 | - | - | 3.6 | 2.2 | - |

| 323 | 6.0 | 4.9 | 3.4 | b | b | 8.1 | - | - | 5.3 | 3.3 | - | ||

| A2 | 275 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 8.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 6.8 | |

| 323 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.0 | b | b | 8.0 | b | b | 5.8 | 3.7 | 8.7 | ||

| A3 | 275 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | - | 5.8 | 5.0 | - | - | 9.1 | |

| 323 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 4.4 | 3.4c | 3.9c | - | 3.9 | 4.9 | - | - | 8.9 | ||

aHomo- and hetero-nuclear coupling constants are given in Hz (±0.1 Hz for JHH, ±0.2 Hz for JHP and ±0.4 Hz for JCP). Temperature is in K.

bOverlap in the spectrum prevented the extraction of the individual coupling constants.

cCoupling constants at 298 K are given because signals for H5′ and H5′′ protons were isochronous at 323K.

1H NMR chemical shifts and base–base stacking interactions

The analysis of base–base stacking interactions with the use of chemical shifts is usually based on the curvature observed in the plots of chemical shifts as a function of temperature. The perusal of proton chemical shift changes as a function of increasing temperature in oligonucleotides 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) showed that H8, H2 and sugar H1′, H2′ and H3′ protons exhibited almost linear dependence between 273 and 343 K. The lack of significant curvature in the plots of chemical shifts (δ) as a function of temperature, in particular in 1 and 2, prevented their analysis in terms of a two-state stack ↔ unstack equilibrium (26). The chemical shift changes of aromatic and sugar proton resonances in the temperature range from 273 to 343 K (Δδtot) were below 0.1 p.p.m. except for H2 protons which showed Δδtot values of up to 0.284 p.p.m. (Table 1). In comparison, ApApA exhibited the overall changes of chemical shifts up to 0.380 p.p.m. in the temperature range from 277 to 348 K (27). H2 protons in 3′,5′-linked adenine oligonucleotides were shown to offer the best indication of stacking interactions without significant interference of factors other than the ring current effects (27,28). The chemical shifts of H8 and H2 in 3′,5′-linked 3 and 4 (except H8 in 5′-terminal residues) showed a slight curvature, but an overall change of the chemical shift in 273–343 K temperature range was comparable with Δδtot values in 2′,5′-linked 1 and 2 (Table 1). An additional set of measurements for 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3), at 10 times lower concentration of 1.3 mM, also showed a slight curvature in chemical shift changes with slightly smaller Δδtot values of up to 0.224 p.p.m. We therefore concluded that the stacking in 1–4 is weak. The small 1H NMR chemical shift changes in all studied oligonucleotides 1–4 reflect continuous (intra)molecular destacking over the temperature range of 273–343 K. It is noteworthy that the stacking interactions are comparable in 2′,5′-linked 1 and 2 and in their 3′,5′-linked analogs 3 and 4. Previous comparisons of the stacking properties in 2′,5′- versus 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides (29–31) showed stronger stacking interactions in the former.

In 1981 Altona and coworkers described a correlation between the extent of stacking and the conformational preference for γ+ rotamers across C4′-C5′ bonds (29). The increased γ+ population in a given residue of an oligomer in comparison to monomeric adenosine 5′-methylmonophosphate (MepA) indicates higher population of stacked states (29). In 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides, 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), the preference for γ+ rotamers at 275 K is from 45 to 64% in all residues (see below and Table 4), which is considerably below the 85% found for MepA at 275 K (29) and clearly shows, if any, a minor fraction of conformers with stacked residues. At higher temperatures the population of γ+ rotamers in 1 and 2 is reduced, which is indicative of destacking. The limitation of such interpretation lies in the assumption that γ torsion angles in individual rotamers in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) are equal to those in MepA and thus contribute to the difference in the limiting coupling constants and therefore γ populations. The population of γ+ rotamers in 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) is <39% at 275 K (Table 4) and therefore suggests very weak intramolecular stacking interactions. It is noteworthy that higher γ+ populations in 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotide 1 in comparison to 3′,5′-linked 3 are in agreement with the previous results of stronger tendency to stack in 2′,5′- in comparison to 3′,5′-linked dimers and linear trimers (29) or in branched oligomeric RNAs (30).

Table 4. Conformational preferences across β, γ and ε torsion angles in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) and 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) at two limiting temperaturesa.

| β | γ | ε | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Residue | T | %βt | %γ+ | %γt | %γ– | εt | ε– | %εt | r.m.s. | ΔJmax |

| 1 | A1 | 275 | - | 60 | 23 | 17 | 232 | 275 | 61 | 0.065 | 0.1 |

| 323 | - | 49 | 26 | 25 | 56 | ||||||

| A2 | 275 | 83 | 55 | 25 | 20 | 243 | 279 | 89 | 0.496 | 0.8 | |

| 323 | 86 | 50 | 23 | 27 | 74 | ||||||

| A3 | 275 | 83 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 323 | 83 | 60 b | 20 b | 20 b | |||||||

| 2 | A1 | 275 | - | 64 | 21 | 15 | 221 | 262 | 53 | 0.142 | 0.2 |

| 323 | - | 53 | 23 | 24 | 26 | ||||||

| A2 | 275 | 67 | 54 | 31 | 15 | 227 | 265 | 67 | 0.514 | 0.6 | |

| 323 | 70 | 53 | 27 | 20 | 55 | ||||||

| A3 | 275 | 70 | 45 | 26 | 29 | 218 | 256 | 70 | 0.405 | 0.6 | |

| 323 | 81 | 50 | 30 | 20 | 28 | ||||||

| A4 | 275 | 96 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 323 | 81 | 59 | 21 | 20 | |||||||

| 3 | A1 | 275 | - | 39 | 32 | 29 | 246 | 345 | 76 | 0.131 | 0.3 |

| 323 | - | - | - | - | 62 | ||||||

| A2 | 275 | 59 | 32 | 33 | 35 | 233 | 295 | 79 | 0.136 | 0.2 | |

| 323 | 78 | - | - | - | 66 | ||||||

| A3 | 275 | 82 | 32 | 33 | 35 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 323 | 79 | 61b | 23b | 16b | |||||||

aThe population of rotamers across β, γ, and ε torsion angles are in %, the values of εt and ε– torsions are in degrees, r.m.s. and ΔJmax are in Hz.

bPopulations of γ rotamers are given at 298 K.

N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium

The conformational equilibria of sugar moieties in oligonucleotides 1–4 were assessed with the use of temperature-dependent 3J1′2′, 3J2′3′ and 3J3′4′ proton–proton coupling constants (for data at two limiting temperatures see Table 2). The experimental 3JHH coupling constants, which were acquired at 11 different temperatures between 273 and 343 K, were interpreted in terms of a two-state N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium (12,32,33). The best fit between the experimental and calculated 3JHH was found through iterative optimization of phase angle of pseudorotation and maximum puckering amplitudes of N (PN and ΨmN) and S (PS and ΨmS) pseudorotamers as well as their respective mole fractions. Pseudorotational analysis showed that N-type pseudorotamers of individual residues in 1–4 (Table 3) exhibit puckering with the phase angles (PN) in the range from –9 to 32° (i.e. between C3′-endo/C2′-exo and C3′-endo canonical forms). Their partners in the south region of conformational space showed PS from 131 to 161° (between C2′-endo/C1′-exo and C2′-endo canonical forms, Table 3). The puckering amplitudes (Ψm) of both N and S pseudorotamers were found between 34 and 37°. The sugar moieties of A1 and A2 residues in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) exhibit preference of 68 and 72% for N-type pseudorotamers at 273 K, respectively (Table 3). The population of the major N-type conformers is decreased from 68 to 49% in residue A1 and from 72 to 58% in residue A2 upon increase of temperature from 273 to 343 K (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, the residue A3 in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) showed almost unbiased pseudorotational conformational equilibrium in the entire temperature range (Fig. 1A).

Table 3. N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibriuma in 1–4.

| Compound | Residue | PN | ΨmN | PS | ΨmS | r.m.s. error | ΔJmax | %N (273 K) | %N (343 K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) | A1 | –7 | 36 | 147 | 36 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 68 | 49 |

| A2 | 14 | 34 | 144 | 34 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 72 | 58 | |

| A3 | 12 | 34 | 158 | 34 | 0.10 | 0.2 | 52 | 49 | |

| 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) | A1 | –9 | 36 | 143 | 36 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 67 | 49 |

| A2 | 0 | 36 | 145 | 36 | 0.14 | 0.3 | 86 | 66 | |

| A3 | –8 | 35 | 131 | 35 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 69 | 57 | |

| A4 | 11 | 35 | 154 | 35 | 0.08 | 0.2 | 60 | 50 | |

| 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) | A1 | –1 | 36 | 158 | 36 | 0.09 | 0.3 | 50 | 33 |

| A2 | 2 | 37 | 151 | 37 | 0.10 | 0.3 | 58 | 36 | |

| A3 | 32 | 34 | 161 | 34 | 0.13 | 0.3 | 59 | 43 | |

| 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4)b | A1 | –1 | 36 | 158 | 36 | - | - | 55 | 34 |

| A2 | 2 | 37 | 151 | 37 | - | - | 60 | 37 | |

| A3 | 2 | 37 | 151 | 37 | - | - | 60 | 38 | |

| A4 | 32 | 34 | 161 | 34 | - | - | 61 | 44 |

aPhase angles of pseudorotation (PN and PS) and maximum puckering amplitudes (ΨmN and ΨmS) are in degrees, temperature is in K, r.m.s. error and ΔJmax are in Hz.

bPseudorotational equilibrium of 4 was evaluated only on the basis of temperature-dependent 3J1′2′ coupling constant with the assumption of North and South conformers as they were found in 3.

Figure 1.

The populations of North conformers as a function of temperature in individual residues in (A) 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), (B) 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), (C) 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and (D) 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4). Straight lines are the best fits through experimental data points. Labels on the straight lines indicate residue numbers.

All four residues in 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) show a preference of >60% for N-type sugar conformation at 273 K (Table 3). The populations of N-type conformers decrease from 67 to 49% for A1, from 86 to 66% for A2, from 69 to 57% for A3 and from 60 to 50% for A4 in 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) with the increase in temperature from 273 to 343 K (Fig. 1B).

3′,5′-linked analogs, 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) show a conformationaly unbiased N ↔ S equilibrium at 273 K in comparison to 2′,5′-linked oligomers 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) (Table 3). The populations of N-type conformers in 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) decrease from 50 to 33% in A1, from 58 to 36% in A2 and from 59 to 43% in A3 with the increase in temperature from 273 to 343 K (Fig. 1C). A comparable decrease in the populations of N-type conformers from 55 to 34% in A1, from 60 to 37% in A2, from 60 to 38% in A3 and from 61 to 44% in A4 has been observed in tetramer 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (4) with the increase in temperature from 273 to 343 K (Fig. 1D).

The van’t Hoff analysis using populations of the N and S pseudorotamers at 11 different temperatures enabled us to calculate the enthalpy and entropy contributions to the drive of the N ↔ S equilibrium for the individual residues in 1–4 (Fig. 2). The bar plots in Figure 2 show that the pseudorotational equilibrium is driven towards major N-type conformers by enthalpy contributions. Entropy terms drive the N ↔ S equilibrium in 1–4 towards S. The conformational purity in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) is reduced at higher temperatures due to the increased entropy contribution, which becomes equal to enthalpy.

Figure 2.

The experimental thermodynamic parameters for N ↔ S equilibrium [ΔH0 (dashed bars), –TΔS0 at 298 K (gray bars), ΔG0 (white bars)] in various adenosine trimers. Individual residues in oligonucleotides are denoted with A1–A4 beginning from the 5′-terminal end. A positive sign of ΔH0, –TΔS0 and ΔG0 denotes a drive of the N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium towards the North-type conformers, whereas the negative sign denotes the drive towards South-type conformers. The values of ΔH0 and ΔS0 were calculated from slopes and intercepts of van’t Hoff plots according to the relation: ln (XS/XN) = –(ΔH0/R)(1000/T) + ΔS0/R. The Pearson correlation coefficients of van’t Hoff plots were –0.995 for A1 in 1, –0.990 for A2 in 1, –0.811 for A3 in 1, –0.991 for A1 in 2, –0.993 for A2 in 2, –0.974 for A3 in 2 and –0.992 for A4 in 2. Thermodynamic quantities for ApApA and 3′d(A2′p5′A2′p5′A) were calculated from reported populations (27,40).

Conformational equilibria along the sugar–phosphate backbone

The population of rotamers across C4′-C5′ bond (torsion angle γ) has been evaluated on the basis of experimental 3J4′5′ and 3J4′5′′ proton–proton coupling constants (Table 2), which have been interpreted with the assumption of the conformational equilibrium between three staggered conformers (34). The results shown in Table 4 indicate that γ+ rotamers predominate in all residues in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2). The populations of the major γ+ rotamers vary from 45 to 64% at 275 K and decrease with an increase in temperature (Table 4). The analysis of populations across C4′–C5′ bonds in 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) and 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) was hampered due the strong overlap of sugar resonances that prevented the analysis in 2′-MOE-A43′,5′ (4) in particular and made it only partly possible in trimer 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3). The populations of γ+, γ– and γt rotamers were comparable in 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) (Table 4), except in A3 residue, where γ+ rotamers were predominant at higher temperatures (61% at 298 K).

The conformational equilibria across C5′–O5′ bonds (torsion angle β) were assessed with the use of the experimental 3JC4′P coupling constants (Table 2) (35). βt conformers were populated by >59% in the temperature range of 275–323 K in 1–3 (Table 4). Small changes in 3JC4′P coupling constants, which were determined from 2D 1H-13C HSQC (digital resolution of ±0.4 Hz) spectra, did not allow us to evaluate minor conformational redistribution across β torsion angle as a function of temperature and make correlations with the other degrees of freedom (Table 4).

The conformational analysis across C2′–O2′ bond (torsion angle ε′, for simplicity named just ε) in 1 and 2, with the use of experimental 3JC3′P, 3JC1′P and 3JH2′P coupling constants, has been performed with the assumption of a two-state εt ↔ ε– conformational equilibrium. A similar assumption is usually made in 3′,5′-linked analogs (14,36). This assumption was supported by our MD simulation on 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1), which showed the equilibrium between only two conformers, one in trans region with ε ∼195° and the other in gauche– region with ε ∼285°. Conformational analysis of coupling constants has shown that εt rotamers in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) occupy angles from 218 to 243°, while the characteristic torsion angles for ε– rotamer are between 256 and 279° (Table 4). εt conformers are slightly preferred in 1 and 2 by 53–89% at 275 K. The two-state εt ↔ ε– conformational equilibrium shifts towards ε– conformers in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) upon the increase in temperature. The precision of 3JCP coupling constants (± 0.4 Hz) at three temperatures (275, 298 and 323 K) hampered our interpretations with the three-parameter Karplus type equations. Additionally, parameters of the Karplus equation that have been derived empirically from data on nucleotides with 3′,5′-linked sugar–phosphate backbone (36–38) are probably different for 2′,5′-linked backbone. Nevertheless, the increase of ε– rotamer population in 1 and 2 is correlated with the increase in the population of S-type conformers. This is in agreement with earlier studies on monomeric 3′-ethylphosphate nucleotides, which have shown that N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium and εt ↔ ε– equilibrium are strongly coupled and exhibit (N, εt) ↔ (S, ε–) equilibrium (14).

Conformational equilibria along glycosidic torsion angles in 1 and 2

The populations of syn- and anti-rotamers around torsion angle χ[O4′-C1′-N9-C4] have been assessed semi- quantitatively by the comparison of intraresidual H1′-H8 versus H2′-H8 and H3′-H8 NOESY cross-peak volumes. The anti orientation of adenine is slightly preferred in the case of A1 residues (i.e. 5′-end) in both 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) at 275 K. The spectral overlap prevented the integration of H2′ and H3′ crosspeaks in all other residues in both 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2). H8-H1′ cross-peaks were, however, well resolved and their volumes were larger than those for A1 in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), which suggests that A2, A3 and A4 residues adopt predominantly syn conformation.

Orientation of MOE group in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2)

Heavy signal overlap of 3′-MOE protons in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) prevented the assignment and extraction of 3JHH coupling constants, which could define the relative orientation of 3′-OCH2CH2O fragments. In addition, the methyl groups of 3′-MOE in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) did not give any NOE cross-peaks with aromatic and sugar resonances, which is in agreement with very fast conformational changes (short correlation time) and implies weak NOE interactions. The 3′-O-CH2CH2-O- fragment is, however, expected to preferentially adopt gauche orientation of vicinal oxygen atoms (39). Our MD calculations on 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) showed comparable preferences of ∼30% for gauche+, gauche– and trans populations for O-C-C-O torsion angles in MOE groups.

DISCUSSION

How do 2′-phosphate and 3′-MOE groups drive pseudorotational equilibria in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2)?

Thermodynamics of a two-state N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium in nucleosides and nucleotides were recently rationalized on the basis of competing steric, gauche and anomeric effects that were evaluated in a quantitative manner (12,15,16). It is noteworthy that the drive of the N ↔ S equilibrium by stereoelectronic forces was evaluated in the absence of any intramolecular stacking interactions due to the intrinsic structural features of mononucleosides and nucleotides. The N ↔ S equilibrium in individual residues of 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) is driven towards N by the anomeric effect of adenine and by the gauche effect of the [O4′-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragment (Fig. 3A), and towards S by the gauche effects of [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment and [N9/1-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragments (Fig. 3B). The steric effects drive N ↔ S equilibrium through the preference of bulky substituents to adopt pseudoequatorial orientation (e.g. adenine would adopt S-type conformation due to the steric effect alone, while 3′-MOE group would prefer N-type sugar conformation in 1 and 2, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Relative orientations of adenine, phosphodiester functionality, 3′-MOE group and other substituents in (A) N- and (B) S-type conformers of non-terminal residues in 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2). The 3′-MOE group adopts pseudoequatorial orientation in the N-type conformation (A). In addition, oxygen atoms of 3′-MOE group which adopt gauche orientation are predisposed for water-mediated H-bonding interactions with 2′-phosphodiester functionality. In S-type conformation the 3′-MOE group adopts less favorable pseudoaxial orientation (B).

It has been shown that the gauche effects of [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′PO3H–] and [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′PO3Et–] fragments are stronger by 1.2 and 0.8 kJ mol–1, respectively, than the gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′H] fragment in 2′-deoxyadenosine (13). Similarly the gauche effect of 3′-ethylphosphate is stronger by 2.3 kJ mol–1 than the gauche effect of 3′-OH in adenosine (14). In 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) the phosphate group is at the 2′-position and thus stabilizes N-type conformers by the gauche effect of [O4′-C1′-C2′-O2′PO2OR–] fragments (Fig. 3A). The preferential stabilization of N-type conformers by 2′-phosphate over 2′-hydroxy functionality is nicely manifested by the additional stabilization of N-type conformation by up to 26 unit % for non-2′-terminal residues in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) (Table 3). The drive towards N-type conformers is perhaps best appreciated through the comparison of thermodynamic parameters depicted in Figure 2. The enthalpy that drives the N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibria towards N-type conformers is opposed by the entropy term of similar strength at 298 K.

To further evaluate the impact of gauche effects in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) we have made comparisons of their conformational properties with those in trimeric adenine oligonucleotides with different substituents at atom C3′. N ↔ S equilibria in non-2′-terminal residues of 3′d(A2′p5′A2′p5′A) are conformationaly strongly biased towards N by ∼94% at 298 K (40) (Table 5). The high conformational purity of sugar moieties in 3′d(A2′p5′A2′p5′A) can be attributed to the gauche effect of the [O4′-C1′-C2′-O2′PO2OR–] fragment and anomeric effect of adenine, which both drive N ↔ S equilibrium towards N. There is no opposing gauche effect of 3′-O substituent, which would drive N ↔ S equilibrium towards S. In comparison, the pseudorotational equilibria in A2′p5′A2′p5′A, where H3′ is substituted with 3′-OH group (29), showed only slight preference for N-type conformers (Table 5). The examination of thermodynamic contributions to the drive of N ↔ S equilibrium nicely illustrates the effect of 3′-H, 3′-OH and 3′-MOE modifications on the sugar conformation in 2′,5′-linked trimers (Fig. 2A). The drop in ΔH° values in 3′-OH and 3′-MOE analogs, in comparison to the parent 3′-deoxy trimer 3′d(A2′p5′A2′p5′A), which is correlated with the reduced stabilization of N-type pseudorotamers, can be explained by the gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment that drives N ↔ S equilibrium towards S-type conformers. It is noteworthy that the gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment is apparently stronger in A2′p5′A2′p5′A in comparison to 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) (Fig. 2 and see below).

Table 5. Comparison of conformational parameters in various 2′,5′- and 3′,5′-linked adenosine trimersa at 298 K.

| Compound | Residue | PN | ΨmN | PS | ΨmS | %N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) | A1 | –7 | 36 | 147 | 36 | 58 |

| A2 | 14 | 34 | 144 | 34 | 68 | |

| A3 | 12 | 34 | 158 | 34 | 52 | |

| 3′d(A2′p5′A2′p5′A)b | A1 | 15 | 31 | 162 | 34 | 93 |

| A2 | 11 | 32 | 162 | 34 | 94 | |

| A3 | 11 | 31 | 161 | 34 | 78 | |

| A2′p5′A2′p5′Ab | A1 | 14 | 33 | 160 | 33 | 55 |

| A2 | 3 | 33 | 148 | 33 | 61 | |

| A3 | 16 | 33 | 159 | 33 | 55 | |

| 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) | A1 | –1 | 36 | 158 | 36 | 41 |

| A2 | 2 | 37 | 151 | 37 | 47 | |

| A3 | 32 | 34 | 161 | 34 | 47 | |

| 2′d(ApApA)b | A1 | 10 | 35 | 168 | 35 | 8 |

| A2 | 10 | 35 | 152 | 36 | 10 | |

| A3 | 10 | 35 | 144 | 32 | 34 | |

| ApApAb | A1 | - | - | - | - | 66 |

| A2 | - | - | - | - | 72 | |

| A3 | - | - | - | - | 63 |

aPhase angles of pseudorotation (PN and PS) and puckering amplitudes (ΨmN and ΨmS) are in degrees, temperature is in K and populations of N-type conformers at 298 K are in %.

Effect of MOE group on the N ↔ S equilibrium in 2′,5′-linked and 3′,5′-linked oligomers

The pairwise comparison of N ↔ S equilibria of A1 and A2 residues in 2′,5′-linked 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and in A2′p5′A2′p5′A at 298 K shows that N-type conformers are preferred by 3 and 7 unit % in the former, respectively (Table 5). N-type conformers of A1 and A2 are preferentially stabilized in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) in comparison to A2′p5′A2′p5′A by ΔΔH0 of 3.1 and 4.2 kJ mol–1, respectively (Fig. 2). The strength of the gauche effect of [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment, which drives N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium towards S is apparently decreased in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1). The weaker gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment could be due to the smaller electron withdrawing nature of MOE group in comparison to OH group. An additional reason for the 3′-MOE group to stabilize N-type conformers, in comparison with the 3′-OH group in 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides, lies in the possibility of water-mediated H-bond formation between the 3′-MOE group and 2′-phosphate oxygen atoms (4). It is reasonable to assume that the ethylenic fragment of the MOE group in all studied oligomers 1–4 adopts a gauche orientation (39). Such orientation is predisposed for water-mediated H-bonding interactions of -OCH2CH2O- fragment with vicinal phosphodiester functionality at 2′ position in 1 and 2 (Fig. 3A). The structural and spatial requirements for water-mediated H-bonding interactions between phosphate oxygens and 3′-O-CH2CH2-O- oxygens were analyzed on a series of structures obtained from our in vacuo MD simulations of 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1). In the final 1 ns of our 3 ns MD simulation A2 residues showed distances between phosphate oxygens and 3′-O-CH2CH2-O- oxygens from 3 to 5 Å, which supports the possibility of water-mediated H-bond formation.

The other possible explanation for the stabilization of N-type conformers in 1 and 2 involves the steric interactions of the 3′-MOE group, which plays an important role in the drive of N ↔ S equilibrium in 3′-MOE-substituted 2′,5′-linked oligonucleotides. It has been shown (12,15,16,41) that bulky substituents in mononucleos(t)ides (e.g. nucleobase) adopt pseudoequatorial orientation (Fig. 3B). In the case of 2′,5′-linked 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2), the MOE group at C3′ adopts pseudoequatorial position in N-type conformation. The gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment is therefore opposed by the steric effect of the 3′-MOE group. This fine tuning of N ↔ S equilibrium in 1 and 2 is in perfect agreement with experimentally determined conformational preferences (Table 5).

The comparison of N ↔ S conformational preferences in both 2′,5′- and 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides gives additional insight into the effects and roles that 3′-MOE as well as 2′-MOE groups play in the drive of pseudorotational equilibria of sugar rings in 1–4. N ↔ S equilibria of A1 and A2 in dApdApdA with the 3′,5′-linked backbone (26) show high conformational bias towards S-type conformers at 298 K (Table 5). The high conformational purity can be attributed to the gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment, which stabilizes S type conformers. The lower population of S-type conformers in the 3′-terminal residue of dApdApdA can be explained by the weaker gauche effect of [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′H] and therefore the weaker drive towards S in comparison to the [O4′-C4′-C3′-3′phosphate] fragment.

The replacement of H2′′ in dApdApdA with 2′-OH group in ApApA shifts the N ↔ S equilibrium strongly towards N with the populations from 63 to 72% at 298 K (Table 5). The shift towards N-type conformers by 58 and 62 unit % for A1 and A2 in ApApA in comparison to dApdApdA can be rationalized by the gauche effect of the [O4′-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragment which drives N ↔ S equilibrium towards N and therefore opposes the gauche effect of the [O4′-C4′-C3′-O3′] fragment. The 2′-OH group of sugar moieties in ApApA is, in addition, involved in the gauche effect of the [N9-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragment, which drives N ↔ S equilibrium towards S, but is apparently weaker. Shift towards N-type conformers can also be promoted by the involvement of the 2′-OH group in H-bonds with vicinal 3′-phosphate oxygens (42).

The comparison of conformational preferences and thermodynamic data for the N ↔ S equilibrium in ApApA and 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) shows that the 2′-MOE group apparently shifts the N ↔ S equilibrium towards S-type conformers by 25 unit % in 3′-non-terminal residues (Table 5). The substitution of 2′-OH group with 2′-MOE affects the strength of two gauche effects that oppose each other in the drive of pseudorotational equilibrium. The gauche effect of the [O4′-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragment drives N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium towards N, while the gauche effect of [N9-C1′-C2′-O2′] fragment drives it towards S conformers. The large shift towards S-type conformers in 2′-MOE-A33′,5′ (3) cannot be explained solely by the gauche effects of the 2′-MOE group. The 2′-MOE group in 3′,5′-linked oligonucleotides adopts sterically less hindered pseudoequatorial orientation in the S-type conformation. S-type conformation is also preferred by the steric effect of the adenine base where it can interact with the vicinal 2′-MOE group. Such stabilization by interactions of the MOE group and adenine could not occur in 2′,5′-linked analogs where the MOE group is at the 3′ position. Pyrimidine nucleosides and nucleotides are, in comparison with their purine counterparts, characterized by a higher conformational bias towards N-type conformations due to the stronger anomeric effects of cytosine and thymine (12). In 2′,5′-linked pyrimidine oligomers the anomeric effect and gauche effect of the 2′-phosphodiester would therefore both drive the N ↔ S equilibrium towards N-type conformers, which would be opposed by the gauche effect of the 3′ substituent. It can be predicted that pyrimidine trimers and tetramers would therefore exhibit higher preferences for the N-type sugar conformation.

In conclusion, trinucleoside diphosphates 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) were prepared as novel modifications of antisense oligonucleotides with unique 2′,5′-phosphodiester linkages and 3′-MOE functionalities. The study of conformational properties of 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) by NMR spectroscopy revealed A-type conformational features that are prerequisite for good antisense hybridization. The interpretation of temperature-dependent 3JHH coupling constants in terms of a two-state N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium gave insight into the thermodynamics of the drive towards N-type conformers by 2′-phosphate groups in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2). 3′-MOE groups in 3′-MOE-A32′,5′ (1) and 3′-MOE-A42′,5′ (2) drive N ↔ S pseudorotational equilibrium additionally towards N-type conformers in comparison to 3′-OH in the analogous trimer and tetramer oligonucleotide. Conformational equilibria around the sugar–phosphate backbone showed a predominance of βt, γ+ and εt rotamers.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of Republic of Slovenia (Grant no. J1-3309-0104) and European Commission (ICA1-CT-2000-70034) for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal S. and Zhao,Q.Y. (1998) Antisense therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 2, 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manoharan M. (1999) 2′-Carbohydrate modifications in antisense oligonucleotide therapy: importance of conformation, configuration and conjugation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1489, 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manoharan M., Kawasaki,A.M., Prakash,T.P., Fraser,A.S., Prhavc,M., Inamati,G.B., Casper,M.D. and Cook,P.D. (1999) Carbohydrate modifications in antisense oligonucleotide therapy: new kids on the block. Nucl. Nucl., 18, 1737–1746. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teplova M., Minasov,G., Tereshko,V., Inamati,G.B., Cook,P.D., Manoharan,M. and Egli,M. (1999) Crystal structure and improved antisense properties of 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl)-RNA. Nature Struct. Biol., 6, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obika S., Nanbu,D., Hari,Y., Andoh,J., Morio,K., Doi,T. and Imanishi,T. (1998) Stability and structural features of the duplexes containing nucleoside analogues with a fixed N-type conformation, 2′-O,4′-C-methyleneribonucleosides. Tetrahedron Lett., 39, 5401–5404. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koshkin A.A., Singh,S.K., Nielsen,P., Rajwanshi,V.K., Kumar,R., Meldgaard,M., Olsen,C.E. and Wengel,J. (1998) LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis of the adenine, cytosine, guanine, 5-methylcytosine, thymine and uracil bicyclonucleoside monomers, oligomerisation and unprecedented nucleic acid recognition. Tetrahedron, 54, 3607–3630. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S.K., Nielsen,P., Koshkin,A.A. and Wengel,J. (1998) LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis and high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chem. Commun., 455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egli M. (1996) Structural aspects of nucleic acid analogs and antisense oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 35, 1895–1910. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herdewijn P. (1996) Targeting RNA with conformationally restricted oligonucleotides. Liebigs Ann., 1337–1348. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egli M. (1998) Conformational preorganization, hydration and nucleic acid duplex stability. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev., 8, 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabahi A., Guidry,J., Inamati,G.B., Manoharan,M. and Wittung-Stafshede,P. (2001) Hybridization of 2′-ribose modified mixed-sequence oligonucleotides: thermodynamic and kinetic studies. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 2163–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plavec J., Tong,W.M. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1993) How do the gauche and anomeric effects drive the pseudorotational equilibrium of the pentofuranose moiety of nucleosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115, 9734–9746. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plavec J., Thibaudeau,C., Viswanadham,G., Sund,C. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1994) How does the 3′-phosphate drive the sugar conformation in DNA. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 781–783. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plavec J., Thibaudeau,C., Viswanadham,G., Sund,C., Sandstrom,A. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1995) The interaction of the 2′-OH group with the vicinal phosphate in ribonucleoside 3′-ethylphosphate drives the sugar–phosphate backbone into unique (S,ε–) conformational state. Tetrahedron, 51, 11775–11792. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plavec J., Thibaudeau,C. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1996) How do the energetics of the stereoelectronic gauche and anomeric effects modulate the conformation of nucleos(t)ides? Pure Appl. Chem., 68, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polak M., Mohar,B., Kobe,J. and Plavec,J. (1998) Anomeric effect in purine nucleosides. Evaluation of the steric effect of a purinic aglycon from the pseudorotational equilibrium of cyclopentane in carbocyclic C-nucleoside 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 120, 2508–2513. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thibaudeau C. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1999) Stereoelectronic Effects in Nucleosides and Nucleotides and their Structural Implications. Uppsala University Press, Uppsala, Sweden.

- 18.Robinson H., Jung,K.E., Switzer,C. and Wang,A.H.J. (1995) DNA with 2′-5′ phosphodiester bonds forms a duplex structure in the A-type conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 117, 837–838. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adah S.A., Bayly,S.F., Cramer,H., Silverman,R.H. and Torrence,P.F. (2001) Chemistry and biochemistry of 2′,5′-oligoadenylate-based antisense strategy. Curr. Med. Chem., 8, 1189–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu D., Kandimalla,E.R., Zhao,Q.Y., Cong,Y.P. and Agrawal,S. (2002) Immunostimulatory properties of phosphorothioate CpG DNA containing both 3′-5′- and 2′-5′-internucleotide linkages. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 1613–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmieder P., Ippel,J.H., van den Elst,H., van der Marel,G.A., van Boom,J.H., Altona,C. and Kessler,H. (1992) Heteronuclear NMR of DNA with the heteronucleus in natural abundance—facilitated assignment and extraction of coupling constants. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 4747–4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Leeuw F.A.A.M. and Altona,C. (1983) Computer assisted pseudorotation analysis of 5-membered rings by means of proton spin spin coupling constants—program Pseurot. J. Comput. Chem., 4, 428–437. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haasnoot C., de Leeuw,F.A.A.M., Huckriede,D., van Wijk,J. and Altona,C. (1993) PSEUROT—a program for the conformational analysis of five membered rings, version 6.0. Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 24.Altona C., Francke,R., de Haan,R., Ippel,J.H., Daalmans,G.J., Hoekzema,A.J.A.W. and van Wijk,J. (1994) Empirical group electronegativities for vicinal NMR proton-proton couplings along a C-C bond—solvent effects and reparameterization of the Haasnoot equation. Magn. Reson. Chem., 32, 670–678. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haasnoot C.A.G., de Leeuw,F.A.A.M. and Altona,C. (1980) The relationship between proton-proton NMR coupling-constants and substituent electronegativities. 1. An empirical generalization of the Karplus equation. Tetrahedron, 36, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsthoorn C.S.M., Bostelaar,L.J., van Boom,J.H. and Altona,C. (1980) Conformational characteristics of the trinucleoside diphosphate dApdApdA and its constituents from nuclear magnetic resonance and circular dichroism studies – Extrapolation to the stacked conformers. Eur. J. Biochem., 112, 95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C.H. and Tinoco,I. (1980) Conformation studies of 13 trinucleoside diphosphates by 360 MHz PMR spectroscopy—a bulged base conformation. 1. Base protons and H1′ protons. Biophys. Chem., 11, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardi A., Martin,F.H. and Tinoco,I. (1981) Comparative study of ribonucleotide, deoxyribonucleotide and hybrid oligonucleotide helices by nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry, 20, 3986–3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doornbos J., den Hartog,J.A.J., van Boom,J.H. and Altona,C. (1981) Conformational analysis of the nucleotides A2′-5′A, A2′-5′A2′-5′A and A2′-5′U from nuclear magnetic resonance and circular dichroism studies. Eur. J. Biochem., 116, 403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glemarec C., Jaseja,M., Sandstrom,A., Koole,L., Agback,P. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1991) Solution structure of branched U3′p5′A3′p5′C(2′p5′G) and its comparison with A3′p5′U(2′p5′G) by 500 MHz NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron, 47, 3417–3430. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sund C., Agback,P., Koole,L.H., Sandstrom,A. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1992) Assessment of competing 2′-5′ versus 3′-5′ stackings in solution structure of branched-RNA by 1H- and 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron, 48, 695–718. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altona C. and Sundaralingam,M. (1972) Conformational analysis of sugar ring in nucleosides and nucleotides—new description using concept of pseudorotation. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 94, 8205–8212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altona C. and Sundaralingam,M. (1973) Conformational analysis of sugar ring in nucleosides and nucleotides—improved method for interpretation of proton magnetic resonance coupling constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 95, 2333–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haasnoot C.A.G., de Leeuw,F.A.A.M., de Leeuw,H.P.M. and Altona,C. (1979) Interpretation of vicinal proton-proton coupling constants by a generalized Karplus relation—conformational analysis of the exocyclic C4′-C5′ bond in nucleosides and nucleotides. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas-J. Roy. Neth. Chem. Soc., 98, 576–577. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lankhorst P.P., Haasnoot,C.A.G., Erkelens,C. and Altona,C. (1984) Carbon-13 NMR in conformational analysis of nucleic acid fragments. 2. A reparametrization of the Karplus equation for vicinal NMR coupling constants in CCOP and HCOP fragments. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 1, 1387–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lankhorst P.P., Haasnoot,C.A.G., Erkelens,C., Westerink,H.P., van der Marel,G.A., van Boom,J.H. and Altona,C. (1985) Carbon-13 NMR in conformational analysis of nucleic acid fragments. 4. The torsion angle distribution about the C3′-O3′ bond in DNA constituents. Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 927–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mooren M.M.W., Wijmenga,S.S., van der Marel,G.A., van Boom,J.H. and Hilbers,C.W. (1994) The solution structure of the circular trinucleotide Cr(GpGpGp) determined by NMR and molecular mechanics calculation. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 2658–2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plavec J. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1995) Reparametrization of Karplus equation relating 3J(C-C-O-P) to torsion angle. Tetrahedron Lett., 36, 1949–1952. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkateswarlu D., Lind,K.E., Mohan,V., Manoharan,M. and Ferguson,D.M. (1999) Structural properties of DNA:RNA duplexes containing 2′-O- methyl and 2′-S-methyl substitutions: a molecular dynamics investigation. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 2189–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doornbos J., Charubala,R., Pfleiderer,W. and Altona,C. (1983) Conformational analysis of the trinucleoside diphosphate 3′d(A2′-5′A2′-5′A). An NMR and CD study. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 4569–4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thibaudeau C., Kumar,A., Bekiroglu,S., Matsuda,A., Marquez,V.E. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1998) NMR conformation of (-)-beta-D-aristeromycin and its 2′-deoxy and 3′-deoxy counterparts in aqueous solution. J. Org. Chem., 63, 5447–5462. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plavec J., Thibaudeau,C. and Chattopadhyaya,J. (1994) How does the 2′-hydroxy group drive the pseudorotational equilibrium in nucleoside and nucleotide by the tuning of the 3′-gauche effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 6558–6560. [Google Scholar]