Abstract

Mice contain a serum factor capable of inactivating some subgroups of murine leukemia viruses. This leukemia virus-inactivating factor (LVIF) is distinct from immunoglobulin and complement; it has been associated with lipoprotein serum fractions and may be an apolipoprotein. The present study demonstrates that some Swiss-derived inbred strains are LVIF negative. Genetic crosses show this factor to be under control of a single gene that maps to distal chromosome 10 at or near the gene encoding a minor serum apolipoprotein, apolipoprotein F (ApoF). To evaluate this gene as a potential candidate for LVIF, the mouse ApoF gene was cloned and sequenced and its expression was assessed in LVIF-positive and -negative mice; no obvious differences were detected, suggesting that LVIF is under the control of a distinct linked gene.

There are major differences among different strains of mice in their susceptibility to murine leukemia viruses (MLVs) and to MLV-induced disease. Genetic crosses between resistant and susceptible mice have identified multiple chromosomal loci responsible for these differences. Many of these genes, like Fv1, Fv2, and Fv4, as well as the various viral receptor loci, have been cloned and are being actively investigated to define their involvement in virus infection.

There remain, however, additional differences among mice in their response to virus infections that are not as well understood. For example, 25 years ago, several laboratories (7, 14) determined that mouse serum contains a factor that inactivates the xenotropic subgroup of the MLVs. This factor, here termed leukemia virus-inactivating factor (LVIF), was found to be stable when exposed to acid pH, ether extraction, freezing, proteases, and brief boiling (12). This factor is separable from immunoglobulin (7, 14) and is also distinct from complement, indicating that it has no relationship to the complement-mediated lysis of oncornaviruses by human sera (3).

Further characterization demonstrated that LVIF is found in the lipoprotein fraction of serum (12) and has the same flotation properties, particle sizes, and electrophoretic charges as lipoproteins. After serum fractionation, LVIF is associated with the triglyceride-rich chylomicrons, the very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs), and the high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), but not the low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) (11, 16). Kane and his colleagues (11) also reported that levels of serum LVIF are affected by diet, and they showed that LVIF-mediated neutralizing activity could be removed by antiserum to apolipoproteins. Characterization of the migratory properties of LVIF showed that it also resembles the apolipoproteins in that its activity can be passively transferred among lipoprotein species (13).

Little has been done to characterize this factor in recent years. In the present study, we demonstrate that this factor is present in the serum of most, but not all, mouse strains. Analysis of genetic crosses between factor-positive and -negative mice determined that LVIF production is controlled by a single locus that we mapped to a position on distal chromosome 10. We also demonstrate very close linkage between this factor and the gene encoding apolipoprotein F (ApoF), and we describe experiments done to evaluate this gene as a candidate for the LVIF serum factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

CAST/Ei mice (CAST) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. NFS/N-Bxv1 mice (NFS) are a congenic strain carrying the Bxv1 provirus from BALB/c on the NFS/N genetic background; this strain was developed and is maintained in our laboratory. NFS/N-RmcSxv mice were similarly bred and carry the Sxv allele of the polytropic/xenotropic MLV receptor locus Rmc1 from Mus musculus domesticus (formerly M. praetextus). SIM/Ut mice were originally obtained from T. Boyse (Sloan Kettering, New York, N.Y.) and are maintained in our laboratory.

CAST males and females were bred to NFS mice, and the F1 hybrids were crossed with NFS to produce first backcross mice (NNC cross). Since LVIF levels can be altered in mice fed a high fat diet (11), all backcross mice were fed a standard diet. Serum samples from parental and backcross mice were obtained by bleeding from tail veins or by cardiac puncture. Additional serum samples from representative inbred strains (see Table 1) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of serum inactivating factor in inbred laboratory and wild mouse strainsalegend

| Strain | % Inactivation |

|---|---|

| Common strains | |

| BALBc/J | 99 |

| 129/J | 97 |

| NZB/B1NJ | 97 |

| CBA/J | 96 |

| DBA/2J | 96 |

| SEA/GnJ | 96 |

| C57L/J | 95 |

| RF/J | 94 |

| MA/MyJ | 93 |

| C3H/HeJ | 92 |

| SM/J | 91 |

| C57BL/6J | 89 |

| P/J | 89 |

| NZW/LacJ | 88 |

| SEC/1ReJ | 87 |

| A/HeJ | 84 |

| AKR/J | 72 |

| NOD/LtJ | 64 |

| Swiss strains | |

| SJL/J | 99 |

| SWR/J | 78 |

| FVB/NJ | 82 |

| SIM/Ut | 25 |

| NFS/N-Bxv1 | 24 |

| NFS/N-Sxv | 19 |

| Wild mouse strains | |

| CZECHII/Ei | 99 |

| CAST/Ei | 90 |

| SKIVE/Ei | 82 |

| MOLF/Ei | 79 |

| SPRET/Ei | 71 |

aPercent inactivation is the reduction in RT activity in virus samples treated for 30 min with a 1:5 dilution of serum from the indicated mouse, compared with virus incubated with an equal volume of medium. Sera were obtained from both males and females, and for some mice sera were pooled from up to five mice. Values from factor-negative strains are underlined.

Viruses, cells, and virus assays.

The viruses used in the infectivity assays were originally obtained from J. Hartley (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, Md.). For these experiments, one polytropic virus, Moloney MCF-HIX (8), and one xenotropic virus, AKR6 (10), were used. The amphotropic virus 4070A (9) was used as a negative control. All three virus stocks were grown in mink lung cells (Mv-1-Lu; ATCC-CCL 64).

Virus titers were assessed by a focus assay or by reverse transcriptase (RT) activity. Aliquots of virus were mixed with equal volumes of mouse serum (up to a 1:50 dilution in medium) at room temperature for 30 min. Virus was then added to mink S+L− cells (19) plated at 2 × 105/60-mm dish with Polybrene (4 μg/ml; Aldrich Chemical Company, Milwaukee, Wis.). Foci were counted 6 to 7 days later.

To determine RT activity, 5 μl of a solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 120 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100 was added to 100 μl of culture supernatant. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, a 25-μl of aliquot was taken and mixed with 25 μl of RT cocktail solution {50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1.2 mM MnCl2, 10 μg of oligo(dT)12-18 per ml, 20 μg of poly(A) per ml, 10 nM [32P]dTTP}. Samples were incubated an additional 2 h at 37°C before the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA. Five microliters of each sample was spotted on DEAE Filtermat (Wallac, Turku, Finland), and the filter was washed three times for 10 min with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at room temperature. The filter was then immersed in 100 ml of 95% ethanol to dehydrate for 5 min. After air drying, the DEAE Filtermat was sealed and counted in an automatic liquid scintillation counter (1450; MicroBeta, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Genome scanning and genetic mapping.

Genomic DNA was prepared by standard methods from livers, tail biopsies, or cells cultured from tail biopsies. PCR amplification of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) was carried out as described previously (5). Selection of SSR markers was based on their location at spaced intervals on all chromosomes and for their high degree of polymorphism among the common strains. Additional distal chromosome 10 markers were selected and typed as indicated below. PCR products were fractionated on 3% gels of MetaPhor agarose (BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, Maine) stained with ethidium bromide. Individual backcross progeny were tested; a pooling strategy was not feasible since amplification was often less efficient with the CAST alleles.

Cloning and sequence analysis of the mouse apolipoprotein F gene.

The human ApoF sequence (4, 25) was used to BLAST search the mouse EST database. Thirteen ESTs that showed more than 70% homology to the human ApoF sequence were obtained from the mouse strain C57BL liver cDNA library (24). These sequences represent a total length of 1,236 bp of cDNA with a poly(A) tail at the 3" end of the aligned sequence. PCR primers were designed based on the assembled EST sequences and were used for cloning and for analysis of genomic structure at the ApoF locus as follows: a, 5"-GGAGCAGGATTGTGGAACTACCG-3"; b, 5"-AGGCAACCAGTGTCTCTACGGTGC-3"; c, 5"-GGTTTGGGCTCTTCAGTTCAGC-3"; d, 5"-GTTGACTTACTACCAGCAGTAGGC-3"; e, 5"-CGGTGTTGTGGAAGAAATAGCC-3"; q, 5"-AGCACCGTAGAGACACTGGTTGCC-3"; r, 5"-GGTGGATGAAGGGCTTGTTAGC-3"; s, 5"-GCCTACTGCTGGTAGTAAGTCAAC-3"; t, 5"-AAATTAGACATGGCTATTTCTTCC-3"; u, 5"-CCACCCATCCATCCATCTACAC-3"; and v, 5"-TGTTCAGGTGGAAGTTAGCCAGC-3".

A PCR product of 1,417 bp was generated from both LVIF-positive and -negative strains (C58/J and NFS, respectively) using primers a and v and was cloned into the pCR-blunt and pCRII-Topo vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and sequenced.

Construction of size-selected genomic libraries.

To construct size-selected genomic libraries, genomic Southern blot analysis was performed to generate a detailed restriction map of the mouse ApoF locus (data not shown). We cloned a 2.3-kb EcoRI/BamHI fragment that contains the mouse ApoF genomic sequence along with about 700 bp 5" and about 200 bp 3" of the 1.4-kb ApoF gene. Total mouse DNA from both LVIF-negative and -positive mice (NFS or CAST) was digested to completion with EcoRI and BamHI, fractionated electrophoretically on a 1.0% agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. DNA was eluted from a gel slice containing fragments of approximately 2.3 kb and was cloned into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of the pBluescript II SK13 vector (21). The ligation mixture was used to transform Escherichia coli XL2-Blue MRF ultracompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Recombinant clones containing the 2.3-kb ApoF DNA were identified by colony hybridization with the 1.4-kb ApoF gene fragment as a probe. The sequence of the 2.3-kb DNA was determined.

An additional pair of genome-typing primers was designed from the 5" flanking region. These are primers X, 5"-TATGGGTGAAAGGGCTGGAGAG-3", and Y, 5"-GCAAATAAGCCAGGGACAGAAAG-3".

Northern and Southern blotting.

Total RNA was isolated from different adult mouse tissues with the Total RNA Isolation Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Approximately 5 μg of total RNA from each tissue was used for Northern blotting. Preparation of RNA samples, electrophoresis, and blotting procedures were as described previously (21).

For Southern blotting, digested DNAs were electrophoresed for 48 h on 0.4% or 1% agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.).

After transfer, the Northern and Southern filters were hybridized with 32P-labeled ApoF DNA (the 1.4-kb PCR fragment). Hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C in a hybridization solution containing 50% formamide. The filter was washed for 20 min in 0.2× SSC, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at room temperature and twice for 20 min in 0.2× SSC, 2% SDS at 65°C and then exposed to X-ray film (XAR5; Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) at −70°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The EMBL accession number for the sequence of the 1.4-kb ApoF gene from the mouse strain C58/J is AF411832. The accession numbers for the sequences of the 2.3-kb fragments containing the ApoF gene from CAST and NFS mice are AF411830 and AF411831, respectively.

RESULTS

Distribution of LVIF in inbred strains.

A previous study had determined that all inbred strains tested contain LVIF, as do the mouse species most closely related to laboratory strains (17). In the present study, we screened sera from the common inbred mice and inbred lines of several wild mouse species for LVIF using both focus and RT assays to assess inactivation (Table 1). For serum samples scored as LVIF positive, virus titers were reduced by more than 60%. For these LVIF-positive samples, the virus titer was reduced, on average, by 88% relative to that of untreated controls. Minimal variability was seen among samples of the same strains, and all serum samples scored as LVIF positive reduced viral titers by at least 62% at the 1:5 serum dilution. At higher dilutions (1:20 or higher), LVIF activity was progressively reduced, with some samples reducing virus titers by only 29 to 50% at a 1:50 dilution. In contrast, amphotropic virus titers were unaffected by exposure to the same serum samples (data not shown). Since the xenotropic, polytropic, and amphotropic virus stocks used here were all grown in mink cells, inactivation is unrelated to specific envelope components contributed by the producer cells. Some of the LVIF-positive sera were exposed to elevated temperature (50°C, 30 min), but this did not alter their ability to inactivate virus (data not shown).

As shown in Table 1, sera from 21 common strains of laboratory mice showed significant virus inactivation, as did the sera from 5 strains derived from wild mouse species. The important exceptions were the NIH Swiss-derived mouse strains NFS and SIM/Ut. For these mice, reduction of virus titer was, at best, 25%, even with undiluted serum samples. This is consistent with the previous observation that serum of some NIH Swiss-derived strains do not inactivate xenotropic MLV (1).

Single gene control of LVIF.

To determine the genetic basis for the production of this factor, we mated factor-negative NFS mice with factor-positive CAST mice, a mouse species of Asian origin selected to maximize the number of polymorphic loci available as markers for genetic mapping. The F1 mice contained LVIF activity at levels comparable to that of the CAST parent, indicating that presence of the factor is dominantly inherited (data not shown).

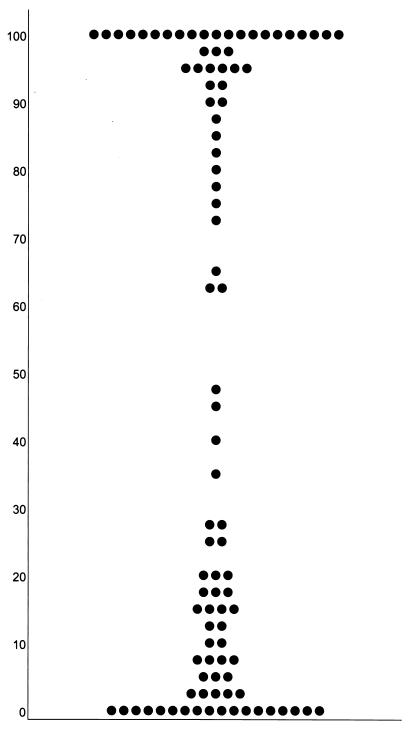

F1 mice were then mated with the factor-negative NFS parent, and 96 NNC backcross mice were tested for serum factor. Each serum sample was tested two to four times using serum dilutions of 1:10 and 1:20. Results from a sample litter are shown in Table 2. The backcross mice could be placed in one of two groups (Fig. 1). Sera from one group of 41 mice reduced virus titers by less than 30%, and these mice were scored as factor negative. Sera from the second group of 48 mice reduced titers by more than 70% and were scored as positive for LVIF. This distribution is consistent with single gene inheritance (χ2 = 0.55, P < 0.5). By the standards chosen to define the two groups, a few samples (seven mice) had weak LVIF activity (62 to 35% inactivation); these were eliminated from the analysis since the mice were not available for retesting.

TABLE 2.

Presence or absence of serum inactivating factor (LVIF) in individual mice of a single litter of the NNC cross

| Mouse | Sex | RT activity (cpm), virus + serum (1:10) | Surviving fraction (%) | LVIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2-1 | F | 18,694 | 97.4 | − |

| H2-2 | F | 3,214 | 11.5 | + |

| H2-3 | M | 19,447 | 101.7 | − |

| H2-4 | M | 3,387 | 14.7 | + |

| H2-5 | M | 18,585 | 90.5 | − |

| H2-6 | M | 20,524 | 105.2 | − |

| No serum | 19,262 |

FIG. 1.

Distribution of LVIF activity in 96 progeny of the NNC cross. Each mouse is represented by a closed circle showing the fraction of RT activity remaining in a virus sample after a 30-min incubation with an equal volume of the mouse's serum (1:10 dilution).

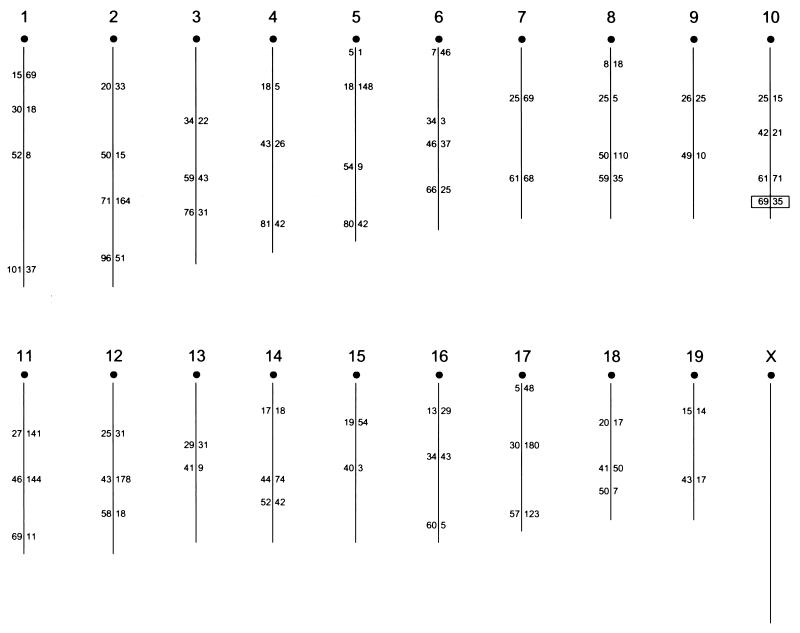

To position the gene on the mouse linkage map, we selected 50 of these mice, half of which had been scored as LVIF positive and half of which were negative. DNA extracted from tail biopsy tissue was used in a genome scan with 58 polymorphic microsatellite markers well distributed over the genome (Fig. 2). This initial scan identified linkage to one marker, D10Mit35, on distal mouse chromosome 10 (recombination = 0.08; χ2= 35.28, P < 0.0005) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Chromosomal positions of the 58 SSR markers typed in NNC backcross mice. The MIT number of each marker is given to the right of each chromosome stick figure; the number on the left represents the centimorgan distance of the marker from the centromere. Linkage was detected between LVIF expression and the boxed marker D10Mit35 (r = 0.08).

We then typed these same 50 mice along with an additional set of 36 mice for additional markers on distal mouse chromosome 10. As shown in Fig. 3A, Lvif could be positioned just proximal to D10Mit269 on distal chromosome 10. We examined the composite linkage map of chromosome 10 (Mouse Genome Database, Mouse Genome Informatics web site, The Jackson Laboratory [http://www.informatics.jax.org/]) as well as the region of conserved synteny on human 12q13-14 to identify potential candidate genes for this factor. The most intriguing candidate identified in this region was apolipoprotein F (Apof). Previous studies had indicated that LVIF is associated with lipoprotein-containing serum fractions and had specifically implicated apolipoprotein (11). Furthermore, the initial studies on human apolipoprotein F had shown ApoF to be predominantly associated with HDL, overlapping the distribution reported for the serum LVIF factor. Therefore, we decided to evaluate this gene as a potential candidate for LVIF.

FIG. 3.

Genetic map location of Lvif on mouse chromosome 10. (A) Loci are listed in centromere-telomere order on the left. Each column represents the chromosome type, with C representing the CAST allele and N the NFS allele. The number of progeny inheriting each chromosome is given at the bottom of each column. (B) Linkage map of distal chromosome 10. The loci are given to the right and the numbers represent the recombination distance between adjacent markers ± the standard error.

Mouse apolipoprotein F.

Human apolipoprotein F has been cloned and sequenced (4, 25). We used the entire human ApoF cDNA sequence to search the mouse EST database, and we identified 13 overlapping EST sequences from the same mouse cDNA library. One of the sequences contained the 5" end, including a UTR of the ApoF RNA, and all the other sequences contained a 3" UTR. The 1,236-bp cDNA sequence assembled from these EST sequences appears to represent a full-length open reading frame (ORF) for ApoF protein. The primers (a and v) designed to amplify the corresponding genomic DNA for the ApoF gene produced a PCR fragment of about 1.4 kb from the C58/J mouse strain, which is about 200 bp longer than the assembled cDNA sequence. This PCR fragment was cloned into the pCRII-topo vector. The size discrepancy is due to a 225-bp intron in the 5" UTR of ApoF (see below).

Southern hybridization analysis using multiple restriction enzymes showed that ApoF is encoded by a single gene in the mouse genome (data not shown). To study the gene structure and regulation of ApoF, we cloned genomic DNA containing ApoF along with flanking sequences. To this end, we constructed size-selected libraries from both LVIF-positive (CAST) and LVIF-negative (NFS) strains of mice. We isolated a single clone from each of the libraries. In both cases the insert is about 2.3 kb and contains ApoF and flanking sequences (see below).

Genetic map location of Apof.

To determine whether ApoF could be responsible for LVIF activity, we mapped the gene, Apof, in the NNC cross to determine the proximity of these genes. Primers X and Y were first used to generate a 551-bp PCR product from the 5" end of the flanking region of ApoF from progeny DNAs. This fragment contains a DdeI restriction site but at different positions in the LVIF-positive and LVIF-negative strains. Thus, digestion of this fragment with DdeI can distinguish the two alleles (results not shown). One recombinant between Lvif and Apof in the 86 progeny was detected; however, this mouse represented a single-locus recombinant in which Lvif had been scored as positive while the other distal chromosome 10 markers were homozygous for NFS alleles, suggesting a possible mistyping (Fig. 3A). Unfortunately, no serum remained from this mouse for retyping. These data indicate that Lvif and Apof are very closely linked, with no confirmed recombinants in 86 mice.

Structural analysis of the ApoF gene in LVIF-positive and -negative mice.

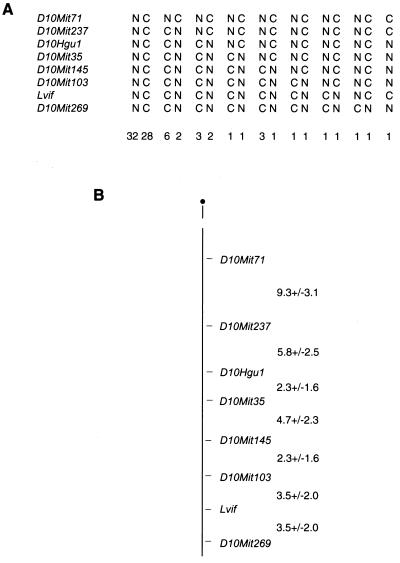

The 1.4-kb ApoF fragment was used as the hybridization probe for DNAs from LVIF-positive (CAST) and -negative (NFS) mice in Southern blotting. ApoF-reactive fragments were detected after digestion with EcoRI, BamHI, XbaI, BagII, and HindIII. No differences were observed in fragment sizes among the DNAs.

To determine if there are any detectable differences in the genomic structure of Apof in C58/J and NFS mice, PCR amplification was performed using overlapping primers covering the entire cDNA. The position of the pairs and the PCR products are shown in Fig. 4. The results show that the products produced from both genomic DNAs have identical lengths, indicating that Apof has no gross alterations in genomic structure in LVIF-negative mice.

FIG. 4.

(A) Genomic structure of Apof. The dashed line indicates the intron sequence. Boxes represent the sequence of the mRNA: the open box represents the transcribed but untranslated regions; the gray box represents amino acids that are absent from the mature ApoF protein; the black box represents the mature ApoF protein. The position of the signal peptide is indicated by an arrow. The three glycosylation sites and four hydrophobic domains are indicated by stars and dotted lines, respectively. (B) PCR primers and predicted products. (C) Gel electrophoresis of PCR products. N, DNA from LVIF-negative (NFS) mice; C, DNA from LVIF-positive (CAST) mice.

Expression of ApoF.

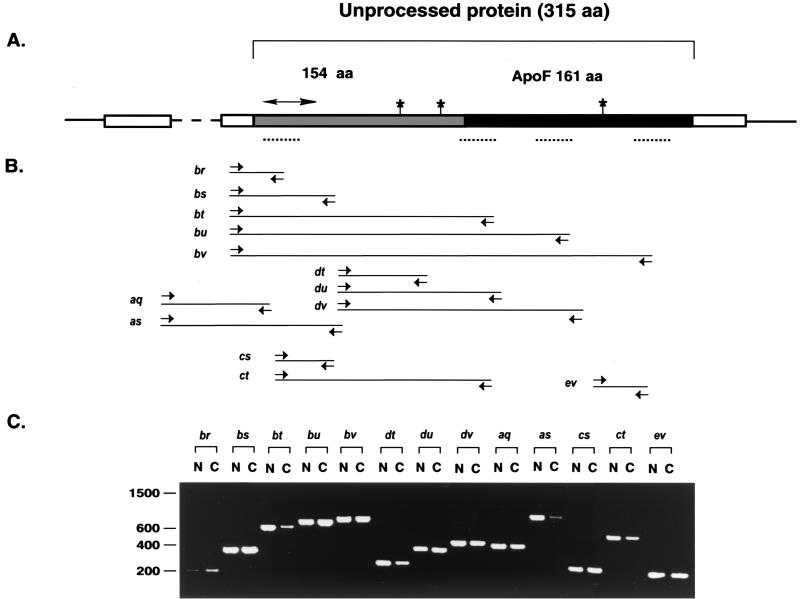

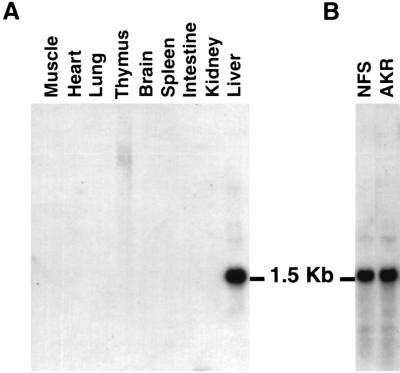

We examined the expression pattern of ApoF by Northern blot analysis. The result showed that a single mRNA transcript of about 1.5 kb was expressed in the liver (Fig. 5), but not in other tissues. This is consistent with the expression pattern of human ApoF (4).

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of ApoF transcripts. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA from various mouse tissues. (B) Northern blot analysis of total liver RNA from LVIF-negative (NFS) and LVIF-positive (AKR) mice. Five micrograms of total RNA was resolved by gel electrophoresis, transferred to a filter, and hybridized with the 1.4-kb ApoF gene fragment as a probe.

We then compared the expression pattern of ApoF between LVIF-negative (NFS) and LVIF-positive (BALB/cJ) strains of mice (Fig. 5). There was no detectable difference in either size or the level of the transcript between these two strains.

Sequence comparison of ApoF in LVIF-positive and -negative mice.

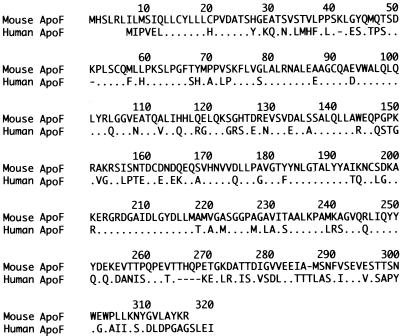

Several independent clones of the 1.4-kb ApoF PCR product from C58/J genomic DNA were sequenced on both strands. The ApoF sequence contains a single ORF encoding a 316-amino-acid protein, starting with a putative ATG translation initiation codon at position 309. The ORF ends with a putative TAG translation termination codon at position 1253. The unprocessed protein contains a putative 22-amino-acid signal peptide at the N terminus. The mature ApoF protein is composed of the C-terminal 161 amino acids after proteolytic cleavage between residues 154 and 155 (Arg/Ser). The predicted amino acid sequence of the mature mouse ApoF protein is 57% identical to that of the human protein, but the longer unprocessed protein is 61% identical to the human protein. It is noteworthy that there are some differences between the two unprocessed proteins. Compared to the human sequence, the unprocessed mouse protein has an extra six amino acids at the N terminus and a four-amino-acid deletion at the C terminus. In addition, there is a four-amino-acid insertion at position 264 of the mouse protein (Fig. 6). It is not clear whether these differences have any effect on function.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of predicted amino acid sequences of mouse and human unprocessed apolipoprotein F. Dots represent amino acid identities and dashed lines represent insertions in mouse ApoF.

Sequencing identified the presence of a 225-bp intron in the 5" UTR. ApoF is exceptional among the apolipoproteins in that the others have four or three exons with the introns at similar locations. The single ApoF intron interrupts the 5" UTR of the gene in a location comparable to the first intron of the other apolipoprotein genes. The other apolipoproteins, however, have a second intron near the signal peptide cleavage site along with one or two additional introns that interrupt the mature peptide (15). These observations together with the insignificant sequence homology between ApoF and the others suggest a much more distant evolutionary relationship for ApoF in this gene family.

Genomic ApoF DNA was also cloned from NFS mice, the strain lacking LVIF activity, and the sequence was compared with that of C58/J mice. This analysis revealed two nucleotide substitutions at positions 55 and 363 in NFS. Both positions have C substituted for T in NFS. Position 55 is in the 5" UTR, and position 363 is a silent substitution in the unprocessed protein region.

The 1,236-bp cDNA assembled from the two EST sequences (AI 528149 and AI 195838) contains a polyadenylation consensus signal (AATAAA) at positions 1206 to 1212. The distance between the termination codon and the poly(A) tail is 194 bp. The conservation of both the polyadenylation signal consensus and the distance between the polyadenylation consensus and the poly(A) addition suggests that the poly(A) in the EST sequences represent an authentic poly(A) tail. The genomic clones that we isolated from both LVIF-positive and LVIF-negative mice contained sequences that extend 184 bp downstream of this 194-bp 3" UTR. Sequence comparisons showed that the genomic sequence encoding this 194-bp 3" UTR and the 184-bp downstream sequence are identical between LVIF-positive and LVIF-negative mice and the 3" UTR of the cDNA sequence is identical to the corresponding genomic sequence.

Northern blot analysis showed that the ApoF transcript is about 1.5 kb in size (Fig. 5). This result and the analysis of the 3" sequence (see above) suggest that the 1,236-bp cDNA assembled from the EST sequences missed about 300 bp of the 5" UTR. The genomic DNA sequence that we isolated extends 700 bp upstream of the 5" end of the assembled 1,236-bp cDNA sequence, and it is thus 400 bp upstream of the presumed transcription start site. Although this 400-bp region contains no obvious TATA element, sequence analysis of this region revealed the presence of a number of other promoter elements which include three CTF1/NF1 binding sites, an MLTF/USF binding site, three AP4 sites, and an AP5 site. The presence of these promoter elements is consistent with the tentative assignment of the 5" end of the ApoF transcription unit to this region, and it is also consistent with the fact that many housekeeping genes have no TATA elements (22, 23). Among the apolipoprotein genes, some, like ApoC-II, have a TATA box (26), while many others, like the ApoL family of genes, have TATA-less promoters (6).

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrate that mice, with the notable exception of some NIH Swiss-derived strains, contain a factor that can inactivate the xenotropic and polytropic MLVs. This strain difference was used in a classical genetic analysis to determine that a single gene controls the presence of this factor. This factor is likely to be the same serum factor described in earlier studies (7, 14) because of its specificity for xenotropic and polytropic MLVs, its absence in some NIH Swiss-derived strains, and its insensitivity to heat inactivation.

This gene, termed Lvif, was positioned on distal mouse chromosome 10. Lvif was mapped at or near Apof, a good candidate gene for LVIF, based on the fact that LVIF has been identified as a lipoprotein and is likely to be an apolipoprotein based on its migratory properties and its inactivation by apolipoprotein antisera (11). The fact that the distribution of human ApoF in HDL overlaps the distribution of LVIF in mouse sera further implicates ApoF. ApoF, a minor serum apolipoprotein, is thought to be involved in transport and/or esterification of cholesterol. While this does not point to an obvious mechanism of virus inactivation involving ApoF, it is known that enveloped viruses, including retroviruses such as human immunodeficiency virus and Friend MLV, have higher cholesterol levels than their host cell membranes (2) and that depletion of cholesterol from the envelope of one enveloped virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, correlates with a decrease in virus infectivity (18). How cholesterol content could affect infectivity is unclear, but cholesterol content can alter membrane fluidity and thickness and thereby affect the function of transmembrane proteins. Our comparative sequence analysis of ApoF, however, in factor-positive and -negative mice failed to identify any amino acid differences within the coding region or any differences within the 5" and 3" UTRs that could result in altered expression of the gene or processing of the protein. Consistent with the sequencing data, no differences were detected in the ApoF message in factor-positive and -negative mice.

We are now expanding our genetic screening of this region of chromosome 10 to identify other potential candidates. The mouse contains at least 14 other apolipoprotein genes, but 3 of these are clustered on chromosome 7 and 3 are on chromosome 9, with the remainder scattered on eight different chromosomes (15). No other apolipoprotein gene has been linked to the ApoF gene. Low-stringency hybridization of genomic Southern blots failed to identify other ApoF-related sequences in the mouse (data not shown), suggesting that we are not missing a related gene in this region. We are now typing additional backcross mice as well as more markers in the region to provide a more precise location for the Lvif gene relative to other expressed genes in the region.

The role of this antiviral activity in the induction and progression of virus-induced disease in the mouse has not been examined. Although LVIF inactivates xenotropic virus, in laboratory mice the spread of these viruses is already restricted, since the cells of laboratory mice are not susceptible to xenotropic virus infection. LVIF-susceptible polytropic viruses, on the other hand, are not only infectious for mouse cells but generally represent the proximal etiological agent in the induction of neoplastic disease. During disease induction, ecotropic viruses recombine with multiple endogenous polytropic proviruses. The appearance of recombinant infectious polytropic viruses is restricted to thymic and other lymphoid tissues (20). The fact that the strains with the highest incidence of virus-induced disease, like AKR, contain the LVIF serum factor indicates that LVIF cannot prevent disease. However, it is possible that LVIF functions to limit the spread of leukemogenic polytropic viruses. We are currently developing congenics in which we are removing Lvif from the AKR genetic background to evaluate its effect on the spread of virus in these mice and on the disease process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yong-Tae Jung and Jonathan Silver for many helpful discussions, Jonathan Silver for some of the RNA samples, and M. Charlene Adamson for excellent technical assistance. We thank Carol Ball for invaluable editorial assistance in proofreading and editing the manuscript and bibliography.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaronson, S. A., and J. R. Stephenson. 1974. Widespread natural occurrence of high titers of neutralizing antibodies to a specific class of endogenous mouse type-C virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:1957-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloia, R. C., H. Tian, and F. C. Jensen. 1993. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5181-5185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper, N. R., F. C. Jensen, R. M. Welsh, Jr., and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1976. Lysis of RNA tumor viruses by human serum: direct antibody-independent triggering of the classical complement pathway. J. Exp. Med. 144:970-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day, J. R., J. J. Albers, T. L. Gilbert, T. E. Whitmore, W. J. McConathy, and G. Wolfbauer. 1994. Purification and molecular cloning of human apolipoprotein F. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 203:1146-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietrich, W., H. Katz, S. E. Lincoln, H. S. Shin, J. Friedman, N. C. Dracopoli, and E. S. Lander. 1992. A genetic map of the mouse suitable for typing intraspecific crosses. Genetics 131:423-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchateau, P. N., C. R. Pullinger, M. H. Cho, C. Eng, and J. P. Kane. 2001. Apolipoprotein L gene family: tissue-specific expression, splicing, promoter regions; discovery of a new gene. J. Lipid Res. 42:620-630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischinger, P. J., J. N. Ihle, D. P. Bolognesi, and W. Schafer. 1976. Inactivation of murine xenotropic oncornavirus by normal mouse sera is not immunoglobulin-mediated. Virology 71:346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischinger, P. J., S. Nomura, and D. P. Bolognesi. 1975. A novel murine oncornavirus with dual eco- and xenotropic properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:5150-5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartley, J. W., and W. P. Rowe. 1976. Naturally occurring murine leukemia viruses in wild mice: characterization of a new “amphotropic” class. J. Virol. 19:19-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartley, J. W., N. K. Wolford, L. J. Old, and W. P. Rowe. 1977. A new class of murine leukemia virus associated with development of spontaneous lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:789-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane, J. P., D. A. Hardman, J. C. Dimpfl, and J. A. Levy. 1979. Apolipoprotein is responsible for neutralization of xenotropic type C virus by mouse serum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:5957-5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leong, J. C., J. P. Kane, O. Oleszko, and J. A. Levy. 1977. Antigen-specific nonimmunoglobulin factor that neutralizes xenotropic virus is associated with mouse serum lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:276-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy, J. A., J. Dimpfl, D. Hardman, and J. P. Kane. 1982. Transfer of mouse anti-xenotropic virus neutralizing factor to human lipoproteins. J. Virol. 42:365-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy, J. A., J. N. Ihle, O. Oleszko, and R. D. Barnes. 1975. Virus-specific neutralization by a soluble non-immunoglobulin factor found naturally in normal mouse sera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72:5071-5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, W. H., M. Tanimura, C. C. Luo, S. Datta, and L. Chan. 1988. The apolipoprotein multigene family: biosynthesis, structure, structure-function relationships, and evolution. J. Lipid Res. 29:245-271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montelaro, R. C., P. J. Fischinger, S. B. Larrick, N. M. Dunlop, J. N. Ihle, H. Frank, W. Schafer, and D. P. Bolognesi. 1979. Further characterization of the oncornavirus inactivating factor in normal mouse serum. Virology 98:20-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nara, P. L., N. M. Dunlop, W. G. Robey, R. Callahan, and P. J. Fischinger. 1987. Lipoprotein-associated oncornavirus-inactivating factor in the genus Mus: effects on murine leukemia viruses of laboratory and exotic mice. Cancer Res. 47:667-672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pal, R., Y. Barenholz, and R. R. Wagner. 1981. Depletion and exchange of cholesterol from the membrane of vesicular stomatitis virus by interaction with serum lipoproteins or poly(vinylpyrrolidone) complexed with bovine serum albumin. Biochemistry 20:530-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peebles, P. T. 1975. An in vitro focus-induction assay for xenotropic murine leukemia virus, feline leukemia virus C, and the feline-primate viruses RD-114/CCC/M-7. Virology 67:288-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe, W. P., M. W. Cloyd, and J. W. Hartley. 1980. Status of the association of mink cell focus-forming viruses with leukemogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 44:1265-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Semenza, G. L. 1998. Transcription factors and human disease. Oxford Monographs on Medical Genetics. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 23.Smale, S. T. 1997. Transcription initiation from TATA-less promoters within eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1351:73-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki, Y., K. Yoshitomo-Nakagawa, K. Maruyama, A. Suyama, and S. Sugano. 1997. Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5"-end-enriched cDNA library. Gene 200:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, X., D. M. Driscoll, and R. E. Morton. 1999. Molecular cloning and expression of lipid transfer inhibitor protein reveals its identity with apolipoprotein F. J. Biol. Chem. 274:1814-1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei, C. F., Y. K. Tsao, D. L. Robberson, A. M. Gotto, Jr., K. Brown, and L. Chan. 1985. The structure of the human apolipoprotein C-II gene. Electron microscopic analysis of RNA: DNA hybrids, complete nucleotide sequence, and identification of 5" homologous sequences among apolipoprotein genes. J. Biol. Chem. 260:15211-15221. (Erratum, 261: 39101986.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]