Abstract

Radiation damage is an inherent problem in x-ray crystallography. It usually is presumed to be nonspecific and manifested as a gradual decay in the overall quality of data obtained for a given crystal as data collection proceeds. Based on third-generation synchrotron x-ray data, collected at cryogenic temperatures, we show for the enzymes Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase and hen egg white lysozyme that synchrotron radiation also can cause highly specific damage. Disulfide bridges break, and carboxyl groups of acidic residues lose their definition. Highly exposed carboxyls, and those in the active site of both enzymes, appear particularly susceptible. The catalytic triad residue, His-440, in acetylcholinesterase, also appears to be much more sensitive to radiation damage than other histidine residues. Our findings have direct practical implications for routine x-ray data collection at high-energy synchrotron sources. Furthermore, they provide a direct approach for studying the radiation chemistry of proteins and nucleic acids at a detailed, structural level and also may yield information concerning putative “weak links” in a given biological macromolecule, which may be of structural and functional significance.

Although radiation damage is an inherent problem in x-ray crystallography, it has not, so far, been widely investigated. It usually is presumed to be nonspecific and to be manifested as a gradual decay in the overall quality of data obtained for a given crystal as data collection proceeds (1–3). The macromolecular crystallographic community has responded to the reality of radiation damage by implementing cryo-techniques (4, 5). However, even during data collection at cryogenic temperatures, using moderate-intensity synchrotron radiation facilities, substantial damage, in terms of loss of resolution, was repetitively observed for large structures like the ribosome (6), as well as for globular proteins (7). At third-generation sources, it is not uncommon for insertion device beamlines to attenuate or defocus the beam (8) simply to lower the available flux density, which is too high even for globular proteins and nucleic acids. To make optimal use of bright synchrotron sources, it is imperative that we come to understand the mechanism of radiation damage and its detailed consequences.

In the following, we present a study on two proteins that provides a description of the molecular consequences of radiation damage at cryogenic temperatures. The initial study, performed in preparation for time-resolved measurements on Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE) (9), showed, in addition to the loss of diffractive power of the crystal and a general increase in atomic B factors, highly specific effects of x-ray irradiation. These included, in particular, breakage of disulfide bonds and loss of definition of the carboxyl groups of acidic residues. Very similar specific radiation damage was observed in studies of a second enzyme, hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL), suggesting the generality of the observed phenomenon. Our studies have direct practical implications for macromolecular crystallographers using bright synchrotron sources, both with regard to data collection and interpretation of the structures obtained. Furthermore, they have served as a starting point for more detailed studies of the mechanism of radiation damage using insertion device x-ray sources at a third-generation synchrotron (R.B.G.R. and S.M., unpublished work). Finally, they show that radiochemistry of macromolecules exposed to synchrotron radiation can be monitored at a detailed structural level and thus may supplement and augment data obtained by use of existing techniques used in radiation research, such as electron spin resonance and electron-nuclear double-resonance spectroscopy (10, 11).

Methods

Materials.

TcAChE is a glycoprotein of subunit molecular weight 65,000. It contains three intramolecular disulfide bonds and an intermolecular disulfide at the C terminus, which participates in dimer formation. TcAChE was purified, subsequent to solubilization with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, by affinity chromatography, as described (12). Trigonal crystals of space group P3121 were grown from 34% polyethyleneglycol 200/0.3 M morpholino-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 5.8, at 4°C (13).

HEWL is a monomeric protein of molecular weight 15,000, containing four intrachain disulfide bonds. It was obtained from Appligene (Illkirch, France). Tetragonal crystals, of space group P43212, were grown from 2–6% NaCl/0.2 M Na acetate, pH 4.7 (14).

Data Collection and Processing.

TcAChE.

Crystals were transferred into mineral oil and flash-cooled by using an Oxford Cryosystems cooling apparatus (Oxford Cryosystems, Oxford, U.K.) operating at 100 K. On a single crystal, a series of nine complete data sets (A–I) were collected on the undulator beamline, ID14-EH4, at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble. The unattenuated beam was used at a wavelength of 0.931 Å. For each data set, 70 frames were collected, with an oscillation range of 0.5° and an exposure time of 3 sec per frame, at a starting angle determined by use of the strategy program (15). The entire duration of collection of each data set was 19 min. Data were processed by using denzo and scalepack (16) (see Table 1). The resolution limit, as determined by <I>/<σI> and Rmerge in the highest resolution shell, was 2.0–2.1 Å for the first three data sets (A–C) and gradually decreased to 3.0 Å for the last data set (I).

Table 1.

Diffraction data statistics AChE

| Data set | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution, Å | 40–2.05 | 40–2.1 | 40–2.1 | 40–2.3 | 40–2.5 | 40–2.65 | 40–2.8 | 40–2.9 | 40–3.0 |

| No unique reflections | 62,401 | 56,543 | 58,334 | 44,671 | 34,910 | 29,417 | 25,004 | 21,801 | 20,415 |

| Redundancy | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉* | 16.4 (2.8) | 13.1 (1.9) | 13.8 (1.6) | 14.2 (1.9) | 13.4 (1.8) | 12.2 (1.7) | 10.7 (1.7) | 8.8 (1.8) | 9.0 (1.9) |

| Completeness (%)* | 99.0 (99.3) | 96.1 (96.9) | 99.0 (99.2) | 99.1 (99.4) | 99.0 (99.4) | 99.0 (99.1) | 98.9 (99.2) | 95.5 (98.6) | 98.8 (99.2) |

| Rmerge, %† | 4.7 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 9.4 | 8.6 |

*Numbers in parentheses indicate statistics for highest resolution shells.

†Rmerge = ∑|I-〈I〉|/∑I.

HEWL.

As part of a longer time series, three data sets were collected on the same undulator beamline, at the same wavelength as for TcAChE, but with an attenuated (ca. 15-fold) beam. The exposure time was 1 sec, and the oscillation range was 0.5° per frame. Total time to collect one data set was 14 min. The attenuated beam had to be used to prevent serious overloads of the low-resolution reflections. Between the second and the third data sets (B and C), the crystal was exposed for 132 sec to the unattenuated beam. The crystal diffracted to better than 1.2 Å for all three data sets, and data processing was carried out as described for TcAChE (see above) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Diffraction data statistics HEWL

| Data set | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution, Å | 25–1.2 | 25–1.2 | 25–1.2 |

| No. unique reflections | 34,095 | 34,062 | 34,143 |

| Redundancy | 3.93 | 3.92 | 3.94 |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉* | 23.7 (4.3) | 23.6 (4.2) | 22.8 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%)† | 95.3 | 95.2 | 95.1 |

| (99.9, 69.2)‡ | (99.9, 68.9)‡ | (100, 67.8)‡ | |

| Rmerge, %§ | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.1 |

*Numbers in parentheses indicate statistics for resolution shell 1.24–1.2 Å.

† Data sets are complete up to 1.4 Å, but incomplete between 1.4 and 1.2 Å because these reflections were measured in the edges of the squared detector.

‡ Numbers in parentheses indicate statistics for resolution shells 1.51–1.42 Å and 1.24–1.2 Å; respectively.

§ Rmerge = ∑|I-〈I〉|/∑I.

Dose Calculations.

A typical flux at the sample position of the utilized beamline is 5 × 1012 photons/sec through a collimator 0.15 mm in diameter. As determined by the crystal size and a calculated absorption coefficient, 1.2% and 2.1% of the photons were absorbed by the crystals of TcAChE and HEWL, respectively, resulting in deposited energies of the order of magnitude of 107 Gγ per data set for TcAChE and 105 Gγ per data set for HEWL. Between the second and third data sets collected on the HEWL crystal, it was exposed to a total absorbed dose of the order of 107 Gγ.

Structure Refinement and Analysis.

For both proteins, all data, up to the high-resolution limit, were used for refinement. For TcAChE, electron density maps were obtained for each data set by routine refinement, using the program cns (17), starting from the model of native TcAChE, namely Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2ACE (13), with minor adjustments obtained from the higher-resolution structure, PDB ID code 1VXR (18) (see Table 3). All six cysteine residues participating in intrachain disulfide linkages were refined as alanines, to avoid any potential bias in the electron density maps (the interchain disulfide was not observed; ref. 19). The programs molscript (20), bobscript (20, 21), and raster3d (22) were used to produce illustrations showing the time course of occurrence of specific structural damage, using electron densities calculated by the program cns (17), and displayed with o (23). For HEWL, structures were refined by using shelxl (24) based on the model of HEWL, namely PDB ID code 194L (M. C. Vaney, S. Maignan, M. Ries-Kautt, and A. Ducruix, personal communication) (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Refinement statistics AChE

| Data set | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R factor, % | 21.6 | 21.4 | 21.2 | 20.3 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 19.4 | 19.9 | 19.1 |

| Rfree, % | 22.9 | 23.0 | 22.7 | 22.0 | 21.6 | 21.9 | 22.3 | 22.6 | 21.6 |

| No. protein atoms | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 | 4,239 |

| No. solvent molecules | 333 | 320 | 314 | 335 | 325 | 297 | 293 | 284 | 260 |

| Average B factor, Å2 | 30.5 | 33.9 | 39.1 | 41.1 | 43.9 | 46.1 | 46.4 | 43.0 | 46.1 |

| rmsd bond length, Å | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| rmsd bond angle, ° | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

rmsd, rms deviation.

Table 4.

Refinement statistics HEWL

| Data set | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| R factor, % | 14.1 | 14.5 | 14.6 |

| Rfree, % | 18.7 | 19.1 | 19.0 |

| No. protein atoms | 1,021 | 1,021 | 1,021 |

| No. solvent molecules | 184 | 184 | 184 |

| No. heterogen atoms | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Average B factor, Å2 | 16.9 | 16.4 | 17.5 |

| rmsd bond length, Å | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| rmsd angle distance, Å | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.029 |

rmsd, rms deviation.

Results

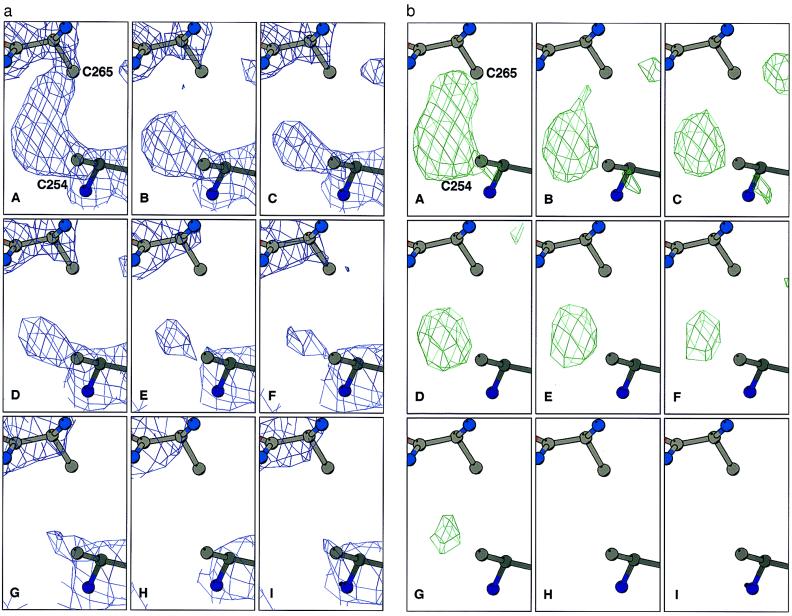

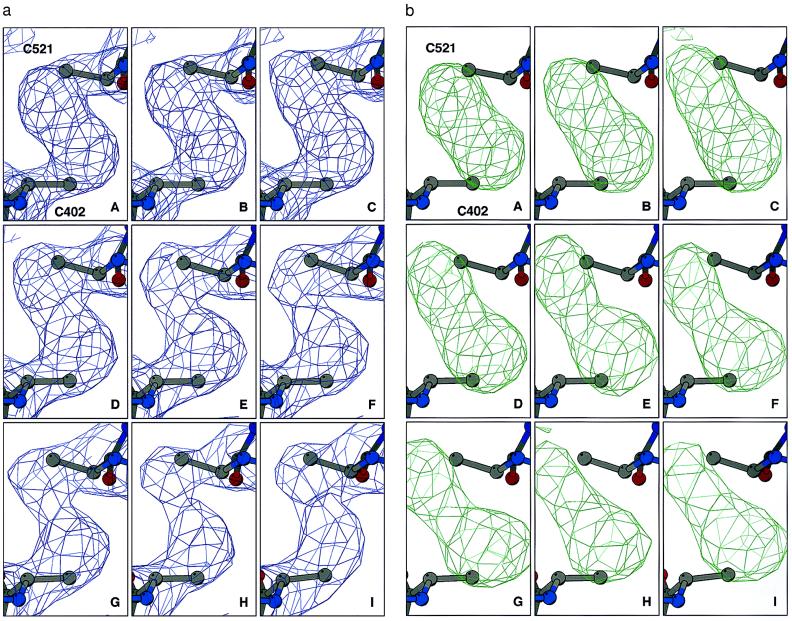

Comparison of the series sequence of refined structures for TcAChE reveals specific and time-dependent changes in electron density in the region corresponding to the disulfide bridge between Cys-254 and Cys-265 (Fig. 1a). To be certain that there was no model bias in these maps, all six cysteine residues taking part in intrachain disulfide linkages were refined as alanines. This permitted unequivocal visualization of the Sγ atoms in difference Fourier maps (Fig. 1b). The other two disulfide bonds, Cys-402–Cys-521 (Fig. 2) and Cys-67–Cys-94 (data not shown), appear substantially more stable over the same period of time. Similar cleavage of S-S bonds has been noted in a number of other x-ray crystallographic measurements on TcAChE using ID14-EH4, in which the cryogenic temperature was varied, and both shorter and longer exposure times were used (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Sequential Fourier maps showing the time course of cleavage of the Cys-254–Cys-265 disulfide bond in TcAChE. Cysteine residues were refined as alanine residues to avoid model bias. (a) 3Fo-2Fc maps, contoured at 1.5 σ. (b) Fo-Fc maps, contoured at 3 σ.

Figure 2.

Sequential Fourier maps showing the time course of structural changes in the Cys-402–Cys-521 disulfide bond in TcAChE. Data collection and refinement were as in Fig. 1. (a) 3Fo-2Fc maps, contoured at 1.5 σ. (b) Fo-Fc maps, contoured at 3 σ.

Detailed inspection of the nine temporal steps for the Cys-254–Cys-265 bond reveals that already in the first data set (Fig. 1bA) some reduction of density is observed for Cys-265Sγ relative to that of Cys-254Sγ, with disappearance of any linking density already apparent in the second data set. Subsequently, it appears as if Cys-265Sγ first moves away from Cys-254γ (Fig. 1 bB and bC), then is detached and finally disappears. Although Cys-254Sγ does not appear to move, its electron density gradually diminishes, and by the eighth step (Fig. 1bH) it is no longer visible.

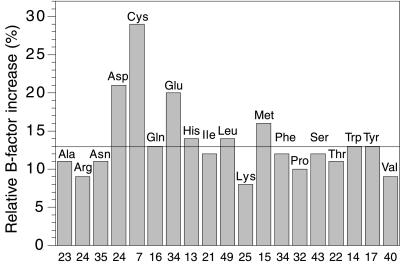

Comparison of the overall structures does not reveal any major change in backbone conformation occurring concomitantly with disulfide bond cleavage. B factors do change as a function of time, but not uniformly throughout the protein. Specifically, the B factors for Cys, Asp, and Glu side chains increase much more than those for other amino acids (Fig. 3). Examination of individual amino acids shows that the rate of increase in B factor for the side chain of Cys-265, for the first three data sets, is the highest in the whole protein and that for the side chain of Cys-254 is only exceeded by that for the side chain of the exposed glutamic acid residue, Glu-306. The side chain of the glutamic acid in the catalytic triad, Glu-327, also shows a marked increase in B factor of 50% in the second (B) compared with the first (A) data set. Although the B factors for histidine residues in general do not increase remarkably (Fig. 3), that for the catalytic triad residue, His-440, increases by 34%.

Figure 3.

Histogram showing the increase in B factors for the side chains of the different types of amino acid in TcAChE as a consequence of synchrotron irradiation. The horizontal line indicates the mean increase in side-chain B factors. The numbers along the x-axis show the number of occurrences of each type of amino acid in TcAChE. The individual bars show the average increase in B factor for each type of amino acid for the second data set (B), as compared with the first data set (A), namely (B factorB − B factorA)/B factorA. Data in this figure, as well as values for increases in B factors mentioned in the text, are derived from models in which the six Sγ atoms of cysteine residues participating in intrachain disulfide linkages were included in the refinement.

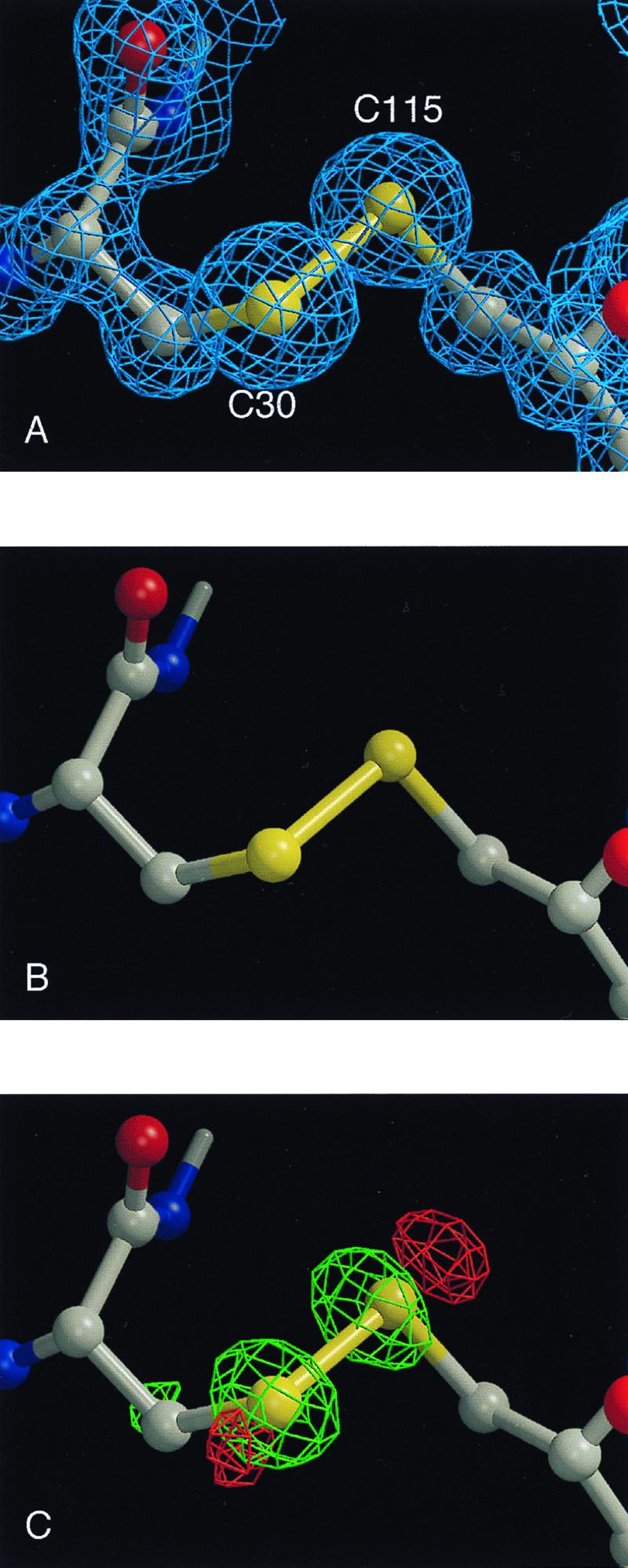

For HEWL, exposure to the unattenuated x-ray beam produced chemical damage similar to that observed for TcAChE. Disulfide bond breakage was the most noteworthy effect. Cys-6–Cys-127 is the most susceptible disulfide bond. The Cys-76–Cys-94 bond is partially cleaved, with an alternative rotamer position for Cys-94Sγ clearly visible. The Cys-30–Cys-115 (Fig. 4A) and Cys-64–Cys-80 bonds appear to be the least susceptible. B factors for aspartic acid residues, and for the two glutamates present in lysozyme, increase more than those for other amino acids. By using the attenuated beam, it was possible to mitigate bond breakage substantially. Specifically, comparison of the first two data sets, collected with the attenuator in place, shows no apparent difference in the electron density maps for the Cys-30–Cys-115 bond (Fig. 4B). However, comparison of the second data set to a third data set collected similarly, but after exposing the crystal to the unattenuated beam, shows clear peaks in the sequential Fourier difference map, indicating significant reduction in electron density of both Sγ atoms in the third data set as compared with the second (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Sequential Fourier maps and difference Fourier maps showing cleavage of the Cys-30–Cys-115 disulfide bond in HEWL as a function of x-ray dose at 1.2-Å resolution. (A) Initial 2Fo-Fc map, contoured at 1.5 σ. (B) Difference Fourier map, wFA − wFB, for two successive data sets collected using an attenuator, contoured at 5 σ (the w refers to sigmaa weighting (39). (c) Difference Fourier map, wFB − wFC, for two successive data sets, between which the crystal was exposed to the unattenuated beam, contoured at 6 σ.

Discussion and Conclusions

The design and construction of increasingly brilliant x-ray sources have brought us to a point at which the number of photons a crystal can absorb before its crystalline diffraction disappears is reached rather fast, even at cryogenic temperatures. This finding is in agreement with predictions made by Gonzalez and Nave (3), which were based on extrapolation of radiation damage occurring during experiments at a second-generation source making use of a polychromatic beam. In the series of data sets collected on a single crystal of TcAChE at the undulator beamline, ID14-EH4, of the third-generation synchrotron source at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, the resolution decreased from 2.0 Å for the first to 3.0 Å for the ninth consecutive data set. The observed decay is not unexpected, because our calculations show that the dose of energy absorbed per data set for TcAChE was of the order of 107 Gγ, i.e., similar to the value of 2 × 107 Gγ that Henderson (25) calculated to be required to totally eradicate crystalline diffraction of proteins.

Our observation of specific radiation damage, including cleavage of disulfide bridges and loss of definition of carboxyl groups of acidic residues, was, however, unexpected. Disulfide bond cleavage by ionizing radiation has been described in a variety of studies in solution (see ref. 26 and references therein). Helliwell (27) reported disulfide bond cleavage in crystalline des-pentapeptide insulin under conditions of synchrotron radiation at room temperature, and Burley, Petsko, and Ringe (personal communication) made similar observations for ribonuclease by using a conventional x-ray source. Under our experimental (cryogenic) conditions, we reproducibly observe a specific order of cleavage, with the Cys-254–Cys-265 bond being the most susceptible in TcAChE and Cys6-Cys127 the most susceptible in HEWL. Breakage of the homologous disulfide, Cys-292–Cys-302, in the x-ray structure of Drosophila melanogaster AChE (M.H., unpublished results), was observed in a data set collected on a second-generation synchrotron source (NSLS-X12c at Brookhaven National Laboratory). Selective cleavage of the Cys-6–Cys-127 disulfide bond in lysozyme was earlier observed in a steady-state radiolysis study in solution (28).

From the histogram of increases in B factors for TcAChE presented in Fig. 3, one can see that the residues most affected by synchrotron radiation, apart from the cysteines, are the acidic residues, glutamate and aspartate. One residue that is particularly affected is the AChE surface residue, Glu-306; another is Glu-327, which is a member of the catalytic triad characteristic of serine hydrolases. In lysozyme, both acidic residues in the active site, namely Glu-35 and Asp-52, are affected, together with the surface residues, Glu-7 and Asp-87. The increases in B factors could be either a consequence of increased mobility or decarboxylation, a known effect of ionizing radiation (29). Acidic residues often are seen in active sites of enzymes, as is the case for both enzymes in the present study. An important consequence of our experiments is the realization that any unusually large B factor, i.e., apparent mobility, seen for such residues, might not be of functional significance, but simply the result of specific radiation damage during structure determination.

Among all the 14 histidine residues in TcAChE, the catalytic triad residue His-440 is the most affected by x-ray irradiation, as shown by the marked increase in its B factor. This finding could be related to the observations of Faraggi and coworkers (28), who showed that pulsed radiolysis affected primarily histidine residues at active sites. However, the increase in B factor also may be coupled to the increase in B factor noted above for the acidic member of the catalytic triad, Glu-327. Our observation that active-site residues are among the most radiation-sensitive residues, suggests that, like disulfide bonds, active site conformations constitute “weak links” or “strained” configurations in protein structures.

An important issue that arises is whether the specific structural changes that we observe are a consequence of “primary” interaction, i.e., between the x-rays and the moieties that suffer specific damage, or “secondary”, i.e., mediated by free radicals generated by the x-rays either within the protein (“direct” damage) or within the solvent (“indirect” damage). The extent to which radiation damage to proteins and nucleic acids is direct or indirect is indeed the subject of controversy (see, for example, the review in ref. 30). Primary damage might affect sulfur atoms preferentially because, at the wavelength used, they have a significantly higher absorption cross section than carbons, oxygens, or nitrogens. Disulfide bonds were earlier shown, in pulse radiolysis studies, to be sensitive to radicals (26) and, therefore, to secondary damage. X-ray irradiation of water molecules in the solvent area releases highly reactive species, including hydrogen and hydroxyl radicals, and hydrated electrons (28, 29). These species should be capable of attacking the protein even under cryogenic conditions (31). There does, indeed, seem to be a correlation between solvent accessibility and susceptibility of disulfides to x-ray damage. Thus Cys-254–Cys-265 in TcAChE, and Cys-6–Cys-127 in HEWL, are the most susceptible disulfides in their respective proteins, and both seem to have the largest solvent accessible surface of the disulfides in that protein. Irradiation has, however, also been shown to cleave disulfide bridges in dry proteins (29). Thus possible involvement of direct radiation damage (30, 32) in generating the specific structural changes that we observe also must be taken into consideration.

Our findings have significant practical implications with respect to x-ray data collection using bright synchrotron sources. Fig. 1 aA, aC, bA, and bC clearly shows that specific damage occurs from the very onset of exposure of the crystal to the x-ray beam. Yet, the resolution of these first three data sets is virtually identical, although some decay in the signal-to-noise ratio for the higher-resolution reflections was observed. These data sets were all complete. However, the redundancy was low as a result of the minimization of the data collection time. Thus, during standard data collection at brilliant undulator beamlines at third-generation synchrotron sources, which aims at high redundancy, the specific radiation damage of the type that we report is very likely to occur (31). Following the trends in Figs. 1 and 2, it is clear that each data set represents the average of a temporal ensemble, which might require extrapolation to zero time. We observed earlier a broken disulfide bond (Cys-254–Cys-265) in TcAChE using a data set that was collected on a second-generation source wiggler beamline (NSLS-X25 at Brookhaven National Laboratory). The Protein Data Bank (33) may contain a substantial number of structures (see e.g., refs. 34 and 35) with broken disulfide bonds: it would be useful if validation programs could help to clarify whether these structures had been affected by radiation damage. Obviously, these programs would benefit from serious investigation of the chemistry and physics underlying radiation damage to protein crystals at powerful synchrotron sources.

The radiation damage we have observed also may explain why collection of multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) data (36) has been problematic at third-generation synchrotron sources. It is noteworthy that virtually all strong third-generation undulator MAD beamlines make routine use of attenuators (8).

In some fields of synchrotron-related research, the free radicals generated by the x-rays actually have been used for studying biological systems in solution (37). For example, folding of an RNA molecule has been followed on a 10-ms time scale by monitoring its hydroxyl radical-accessible surface (38). We anticipate that once the mechanism(s) underlying radiation damage in single crystal protein crystallography is better understood it should be possible to use the wealth of sequential information generated as a valuable tool in radiation chemistry and biology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arthur Grollman, Lev Weiner, and Martin Caffrey for valuable discussions and Deborah Fass for critical and constructive reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the U.S. Army Medical and Materiel Command under Contract No. DAMD17–97-2–7022, the European Union 4th Framework Program in Biotechnology, the Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure and Assembly (Rehovot, Israel), and the Dana Foundation. The generous support of Mrs. Tania Friedman is gratefully acknowledged. R.B.G.R. acknowledges support from the Training and Mobility of Researchers Access to Large Scale Facilities Contract ERBFMGECT980133 to the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Grenoble Outstation, and I.S. is Bernstein-Mason Professor of Neurochemistry.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- TcAChE

Torpedo californica AChE

- HEWL

hen egg white lysozyme

Footnotes

Data deposition: The nine structures of AChE and the structure of HEWL, collected at 100 K, have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes 1QID, 1QIE, 1QIF, 1QIG, 1QIH, 1QII, 1QIJ, 1QIK, and 1QIM and 1QIO, respectively.

References

- 1.Blundell T L, Johnson L N. Protein Crystallography. New York: Academic; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sygusch J, Allaire M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1988;44:443–448. doi: 10.1107/s0108767388001394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez A, Nave C. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:874–877. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope H. Acta Crystallogr B. 1988;44:22–26. doi: 10.1107/s0108768187008632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garman E F, Schneider T R. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;29:211–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yonath A, Harms J, Hansen H A, Bashan A, Schlunzen F, Levin I, Koelln I, Tocilj A, Agmon I, Peretz M, et al. Acta Crystallogr A. 1998;54:945–955. doi: 10.1107/s010876739800991x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen D J, Noble M E, Garman E F, Papageorgiou A C, Johnson L N. Structure (London) 1995;3:467–482. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh M A, Dementieva I, Evans G, Sanishvili R, Joachimiak A. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:1168–1173. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999003698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravelli R B G, Raves M L, Ren Z, Bourgeois D, Roth M, Kroon J, Silman I, Sussman J L. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:1359–1366. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998005277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sevilla M D, D'Arcy J B, Morehouse K M. J Phys Chem. 1979;83:2887–2892. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz H M, Swartz S M. Methods Biochem Anal. 1983;29:207–323. doi: 10.1002/9780470110492.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman J L, Harel M, Frolow F, Varon L, Toker L, Futerman A H, Silman I. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:821–823. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raves M L, Harel M, Pang Y-P, Silman I, Kozikowski A P, Sussman J L. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drenth J. Principles of Protein X-Ray Crystallography. Berlin: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravelli R B G, Sweet R M, Skinner J M, Duisenberg A J M, Kroon J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:551–554. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otwinowski Z. In: Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend: Data Collection and Processing, 29–30 January, 1993. Sawyer L, Isaacs N, Bailey S, editors. Daresbury, U.K.: Science and Engineering Research Council Daresbury Laboratory; 1993. pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millard C B, Koellner G, Ordentlich A, Shafferman A, Silman I, Sussman J L. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9883–9884. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sussman J L, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I. Science. 1991;253:872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraulis P. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esnouf R M. Acta Crystallogr D. 1999;55:938–940. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998017363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merritt E A, Murphy M E P. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:869–873. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones T A, Zou J-Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheldrick G M. In: Recent Advances in Phasing: Proceedings of the CCP4 Study Weekend. Wilson K S, Davies G, Ashton W, Bailey S, editors. Daresbury, U.K.: Daresbury Laboratory; 1997. pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson R. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1990;248:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Sonntag C. The Chemical Basis of Radiation Biology: Radiobiology. London: Taylor & Francis; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helliwell J R. J Crystallogr Growth. 1988;90:259–272. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faraggi M, Ferradini C, Houee-Levin C, Klapper M H. In: Radiation Research 1895–1995. Hagen U, Harder D, Jung H, Streffer C, editors. Vol. 2. Wurzburg, Germany: Universitatsdruckerei H. Sturtz AG; 1995. pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander P, Lett J T. In: Comprehensive Biochemistry. Florkin M, Stotz E, editors. Vol. 27. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1967. pp. 267–356. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Symons M C R. Radiat Phys Chem. 1995;45:837–845. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange M, Weiland B, Huttermann J. Int J Radiat Biol. 1995;68:475–486. doi: 10.1080/09553009514551441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones G D, Lea J S, Symons M C, Taiwo F A. Nature (London) 1987;330:772–773. doi: 10.1038/330772a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sussman J L, Lin D, Jiang J, Manning N O, Prilusky J, Ritter O, Abola E E. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:1078–1084. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998009378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burmeister W P, Gastinel L N, Simister N E, Blum M L, Bjorkman P J. Nature (London) 1994;372:336–343. doi: 10.1038/372336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burling F T, Weis W I, Flaherty K M, Brünger A T. Science. 1996;271:72–77. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hendrickson W A. Science. 1991;254:51–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1925561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng A, Caffrey M. Biophys J. 1996;70:2212–2222. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79787-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sclavi B, Sullivan M, Chance M R, Brenowitz M, Woodson S A. Science. 1998;279:1940–1943. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5358.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Read R J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1986;42:140–149. [Google Scholar]