Abstract

While many herpes simplex virus (HSV) structural proteins are expressed with strict-late kinetics, the HSV virion protein 5 (VP5) is expressed as a “leaky-late” protein, such that appreciable amounts of VP5 are made prior to DNA replication. Our goal has been to determine if leaky-late expression of VP5 is a requirement for a normal HSV infection. It had been shown previously that recombinant viruses in which the VP5 promoter was replaced with promoters of other kinetic classes (including a strict late promoter) exhibited no alterations in replication kinetics or virus yields in vitro. In contrast, here we report that alterations in pathogenesis were observed when these recombinants were analyzed by experimental infection of mice. Following intracranial inoculation, a recombinant expressing VP5 from a strict-late promoter (UL38) exhibited an increased 50% lethal dose and a 10-fold decrease in virus yields in the central nervous system, while a recombinant expressing VP5 from an early (dUTPase) or another leaky-late (VP16) promoter exhibited wild-type neurovirulence. Moreover, following infection of the footpad, changing the expression kinetics of VP5 from leaky-late to strict-late resulted in 100-fold-less virus in the spinal ganglia during the acute infection than produced by either the parent virus or the rescued virus. These data indicate that the precise timing of appearance of the major capsid protein plays a role in the pathogenesis of HSV infections and that changing the expression kinetics has different effects in different cell types and tissues.

Lytic gene expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) can be divided into three rough classes of viral transcripts: immediate-early (α), early (β), and late (γ) (for a review, see reference 18). The temporal regulation of these classes occurs at the level of transcription and is dictated primarily by differences in promoter structure (6, 7, 9, 20). α transcripts are expressed in the absence of de novo viral protein synthesis and encode proteins important for the transactivation and regulation of viral transcription (14, 16). The products of the β transcripts are primarily proteins involved in the replication of viral genomes. As replication of viral DNA ensues, α and β transcription decreases and gives way to increasing γ transcription. The γ transcripts encode the majority of proteins involved in the structure, maturation, and morphogenesis of virions. The γ transcripts are further divided into two subclasses, leaky-late (γ1) and strict-late (γ2), distinguished by their sensitivity to inhibitors of viral DNA replication (1, 17).

The sequential and coordinated timing of transcription has undoubtedly been selected for and fine tuned over time to balance limited cellular resources with efficient viral replication and spread. Therefore, since HSV-1 γ1 genes are expressed at both early and late times, it was postulated that a biological requirement for their expression both prior to and after DNA replication might exist. The HSV major capsid protein VP5 (a product of UL19) is a γ1 gene, and while it is maximally expressed at late times, abundant transcription can be detected by 4 h postinfection. Since VP5 is a key virion component, VP5 null mutants do not form capsids and fail to process newly synthesized DNA into unit-length genomes (4, 12).

To evaluate whether there is a requirement for VP5 expression at early times during an infection, recombinant viruses were generated in which the native VP5 promoter (γ1) was replaced with either a strict-late (UL38, another capsid protein), a strong early (UL50 or dUTPase), or an equal-strength leaky-late (VP16) promoter (10). These studies examined the multistep growth kinetics of VP5 promoter replacement recombinants in mouse embryo fibroblasts, rabbit skin cells (RSC), Vero cells, and serum-starved or quiescent human lung fibroblasts. The results indicated that recombinants and their rescued versions replicated to wild-type titers on these cell lines, and it was concluded that the expression of VP5 is not critical for viral replication in cultured cells (10).

While there was no apparent effect of changing VP5 expression kinetics in vitro, we hypothesized that early expression of VP5 could be required in vivo. Therefore, the promoter replacement recombinants were assessed for their neurovirulence, neuroinvasiveness, and replication in vivo relative to the parent virus (HSV-1 strain KOS) and the VP5 promoter rescued virus. Intracranial (i.c.) inoculation of mice with a recombinant containing the native leaky-late (VP5) promoter replaced with the strict-late (UL38) promoter resulted in at least a 20-fold reduction in virulence, with an 8-fold decrease in virus yield within the central nervous system (CNS). Following footpad inoculation of mice, the recombinant expressing VP5 under control of the strict-late (UL38) promoter exhibited a 100- to 1,000-fold reduction in virus levels in the spinal ganglia compared to its parent and rescued virus and was not detected in the spinal cord. This suggests a restriction in either neuronal replication or ability to spread in the nervous system. Rescuing the UL38 promoter construct (to its native VP5 promoter) restored wild-type neurovirulence and replication properties.

From this study, we conclude that altering the VP5 expression kinetics from leaky-late to strict-late results in reduced virulence, neuronal replication, and dissemination through the nervous system. This work suggests that expressing the virion protein VP5 at early times confers a replication advantage in sensory neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

RSC, Vero, and Neuro-2a mouse neuroblastoma cells were maintained at 37°C under a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. RSC were propagated in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM; Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 5% calf serum (Gibco-BRL) and antibiotics (250 U of penicillin and 250 μg of streptomycin/ml) and 292 μg of l-glutamine/ml. Neuro-2a cells, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line, were obtained from and American Type Culture Collection and maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biological), antibiotics, glutamine and nonessential amino acids (Gibco-BRL). Neural bulb cells were prepared are previously described (8, 15) and maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics, glutamine, and nonessential amino acids. Vero cells were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics, and glutamine. Vero cells were used for the growth and titration of viruses in this study.

Viruses.

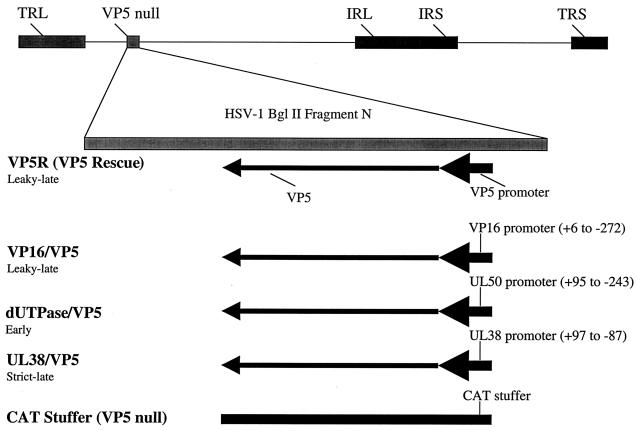

The construction and characterization of the promoter-substitution viruses used in this study are described in detail elsewhere (10). All viral recombinants were constructed in the background of the parent strain HSV-1 KOS. Briefly, the VP5 “rescued” virus was obtained by rescuing a VP5 null virus (4) with the BglII N fragment containing the full-length VP5 promoter and coding region. The VP16/VP5 recombinant virus contains the VP16 promoter from −276 to +6 inserted into the VP5 locus, replacing the VP5 promoter from −36 to +20, which contains the TATA box and initiator element. Similarly, the UL38/VP5 recombinant virus contains the UL38 promoter from −97 to +87, and the dUTPase/VP5 recombinant virus contains the dUTPase promoter from −243 to +95, both inserted into the VP5 locus, replacing the VP5 promoter. The UL38/VP5 recombinant was rescued using the BglII N fragment (described above). As a negative control, the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT)/VP5 recombinant virus was constructed, which contains a 300-bp region of the CAT gene inserted as a stuffer into the VP5 locus. This virus is phenotypically VP5 negative and therefore cannot be propagated outside of a VP5 helper cell line.

In vitro replication assays.

Neuro-2a, Vero, or primary neural bulb cells were seeded on six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. The following day the monolayers were infected with 100 PFU of virus per well, and after absorption for 1 h at 37°C, the inoculum was removed and the monolayers were overlaid with medium. The infections were harvested at the appropriate time points by scraping the monolayers into the medium, after which the suspension was subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. The infectious yield was determined by titration on Vero cell monolayers.

Determination of relative virulence following i.c. inoculation of mice.

Four- to six-week-old outbred Swiss-Webster mice (Simonsen Labs) were anesthetized and inoculated with 0.01 ml of 10-fold serial dilutions of each recombinant into the left cerebral hemisphere. Five mice per virus per dose were inoculated, and PFU per 50% lethal dose (LD50) endpoints were determined (13).

Determination of relative amounts of viral replication in the mouse CNS.

Four- to six-week-old outbred Swiss-Webster mice were anesthetized and inoculated with 0.01 ml of medium containing either 103 or 102 PFU of each recombinant into the left cerebral hemisphere. At 1, 2, 3, and 4 days postinfection, four mice per dose per virus were sacrificed, and their brains were removed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized and titered for infectious virus on RSC as previously described (2, 3).

Assay of in vivo replication of recombinants following footpad inoculation.

Four- to six-week-old outbred Swiss-Webster mice were infected with 2 × 105 PFU of each recombinant on both rear footpads as previously described (2, 3). At 1, 3, 5, and 7 days postinfection, four mice per recombinant per time point were euthanized, and the feet, spinal ganglia, and spinal cords were dissected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total infectious virus present in each tissue was determined as described previously (3). Briefly, the combined feet, spinal ganglia, and spinal cords for each time point were homogenized as 10% (wt/vol) suspensions in MEM and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min to clear cell debris. Infectious virus present in each sample was determined by a standard plaque assay on RSC. The MEM used for homogenates of the feet was supplemented with 2× antibiotics (500 U of penicillin and 500 μg of streptomycin/ml) and amphotericin B (5 μg/ml).

RESULTS

Evaluation of relative virulence of promoter substitution recombinants.

A previous study had examined three recombinants (Fig. 1) in which the native VP5 promoter (leaky-late) was replaced with either the VP16 promoter (leaky-late), the dUTPase promoter (early), or the UL38 promoter (strict-late) to assess whether the leaky-late expression kinetics of VP5 played a measurable role in HSV replication. The inability to detect a significant in vitro replication defect after testing a number of cell lines led to the conclusion that the leaky-late kinetics were not essential for HSV replication (10). It remained possible, however, that early expression of VP5 might confer a replication advantage on some aspect of HSV's in vivo replication cycle.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of promoter substitutions in the VP5 locus. The recombinants were generated by rescue of a VP5 null mutant using either a cloned fragment containing the native VP5 gene (VP5R or VP5 rescued virus), or plasmids containing the VP5 coding region with promoter substitutions. The fragments of the VP16, dUTPase, and UL38 promoters that were used to replace the VP5 promoter (from −36 to +20) are indicated. As a control, the CAT/VP5 recombinant virus was constructed, which contains a 300-bp region of the CAT gene inserted as a stuffer into the VP5 locus.

To address this possibility, we evaluated the virulence characteristics of the three promoter substitution recombinants following i.c. inoculation of mice. As the data in Table 1 indicate, the UL38/VP5 recombinant, which expresses VP5 from a strict-late promoter, is less virulent, with a 9- and 30-fold-higher i.c. LD50 than the VP16/VP5 or the dUTPase/VP5 recombinant, respectively. It should be noted that substituting an early promoter (dUTPase) or a leaky-late promoter similar in strength to the VP5 promoter (VP16) had no detectable effect on virulence in this assay.

TABLE 1.

Determination of i.c. LD50s for the promoter substitution recombinantsa

| Recombinant | No. of mice surviving/5 per group at virus dose:

|

i.c. LD50 (PFU) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PFU | 10 PFU | 100 PFU | 1,000 PFU | ||

| UL38/VP5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | >1,000 |

| VP16/VP5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 175 |

| dUTPase/VP5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 32 |

Five mice per virus per dose were inoculated with the indicated number of PFU in a volume of 0.01 ml into the left cerebral hemisphere. The numbers represent survivors per total number of mice infected.

To confirm that changing the kinetics of expression from leaky-late to strict-late was responsible for the decreased virulence observed for the UL38/VP5 recombinant in the mouse, the recombinant was rescued with the BglII N fragment, spanning the entire VP5 promoter and coding region (see Materials and Methods). When tested for virulence following i.c. inoculation, the rescued virus (UL38R) exhibited virulence comparable to that of the parent virus, HSV-1 strain KOS (Table 2). Therefore, altering the expression kinetics of VP5 from leaky-late to strict-late resulted in attenuated neurovirulence.

TABLE 2.

Determination of the i.c. LD50 for the UL38 rescued virusa

| Recombinant | No. of mice surviving/10 per group at virus dose:

|

i.c. LD50 (PFU) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 PFU | 100 PFU | 1,000 PFU | ||

| UL38/VP5 | 10 | 8 | 6 | >1,000 |

| UL38 rescue | 8 | 4 | 1 | 57 |

| Parent | 7 | 3 | 1 | 33 |

Ten mice per virus per dose were inoculated with the indicated number of PFU in a volume of 0.01 ml into the left cerebral hemisphere. The numbers represent survivors per total number of mice infected from two separate experimental groups of animals.

Ability of UL38/VP5 recombinant to replicate within the mouse CNS following i.c. inoculation.

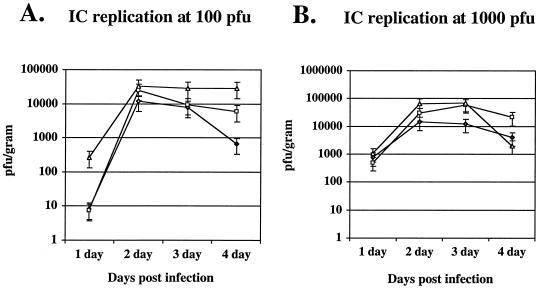

To assess whether the UL38/VP5 recombinant's attenuation in virulence following i.c. inoculation was due to a defect in CNS replication, mice were infected i.c. with either the UL38/VP5 recombinant, its rescued virus, or the parental strain (HSV-1 KOS) at 100 and 1,000 PFU. Yields of infectious virus were determined from four mice per time point per virus at daily intervals through 4 days postinfection (Fig. 2). At the higher inoculum (1,000 PFU), the UL38/VP5 recombinant showed a statistically significant reduction in virus yield from the CNS at postinfection day 3, and a similar lower yield than the rescuant at postinfection day 4, though at this later time point the decrease was not significantly different from the parent. At the lower inoculum (100 PFU), which should be better able to identify subtle differences in viral replication, the UL38/VP5 recombinant showed a statistically significant 10-fold-lower virus yield compared to both its rescuant and parent at postinfection day 4.

FIG. 2.

Replication of the UL38/VP5 recombinant in the mouse CNS following i.c. inoculation. The UL38/VP5 recombinant (⧫) was evaluated relative to its rescued virus (UL38R, □) and the parent strain (HSV-1 KOS, ▵) for its ability to replicate in the CNS. Four mice per time point per dose per virus were inoculated i.c. with either 100 or 1,000 PFU. At the indicated times, the brains were removed and titrated for infectious virus. The yields are presented as PFU per gram of tissue.

Therefore, while there was no statistically significant reduction in virus yields between the UL38/VP5 recombinant and its rescued virus or parent before postinfection day 3, there was a significant reduction after day 3 at both 100 and 1,000 PFU. Even though there is some scatter in the early data points, the data suggested that changing the VP5 promoter from leaky-late to strict-late results in some decrease in viral replication in the CNS.

Assay of in vivo replication of recombinants following footpad inoculation.

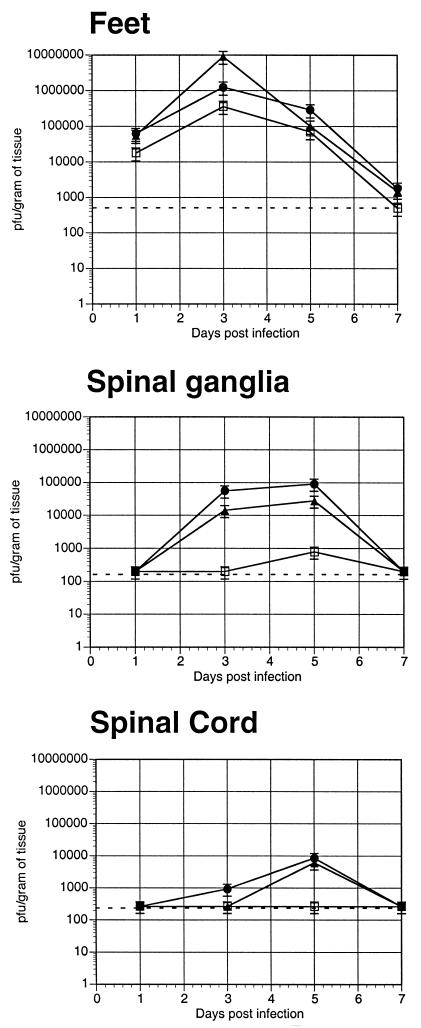

Because the decrease in virus yields observed in the CNS was subtle and not apparent until after postinfection day 3, we wished to examine the replication kinetics of the UL38/VP5 recombinant following a more natural route of infection that would channel the virus through a primarily neuronal replication pathway. To address this, mice were infected on both rear footpads with 106 PFU of either the UL38/VP5 recombinant, its rescued virus, or the parental strain (HSV-1 KOS). At intervals of 1, 3, 5, and 7 days postinfection, four mice per virus per time point were sacrificed, and the feet, spinal ganglia, and spinal cord were dissected and titrated for infectious virus.

As shown in Fig. 3, there was no significant difference in virus yields observed in the feet at any of the time points, suggesting that the UL38/VP5 recombinant is not restricted in replication in the epithelium of the mouse foot. The picture was different following entry of the virus into the nervous system. After entry into the spinal ganglia, the UL38/VP5 recombinant produced detectable yields of virus only at postinfection day 5, and then at 100-fold lower titers than its rescued virus. The rescued virus and the parent were detected as early as 3 days postinfection and showed similar infection kinetics.

FIG. 3.

Ability of the viral recombinants to replicate and spread following mouse footpad inoculation. The UL38/VP5 recombinant (□) was evaluated relative to its rescued virus (UL38R) (•) and the parent strain (HSV-1 KOS) (▴) for its ability to replicate and spread withinthe nervous system of the mouse following footpad inoculation. Four mice per time point per dose per virus were inoculated with 2 × 106 PFU of each virus. At the indicated time points postinfection, four mice per virus per time point were sacrificed, and feet, spinal ganglia, and spinal cords were dissected, homogenized, and titrated for the presence of infectious virus. The values reported are PFU per gram of tissue. The dotted line indicates the experimentally determined limit of sensitivity for detection of virus in each tissue, and data points that fall on the line indicate that no virus was detected at those time points.

The restriction exhibited by the UL38/VP5 recombinant was even more dramatic at the next major site of neuronal replication, the spinal cord. While mice infected with the rescued virus and the parent yielded 8,000 to 10,000 PFU in the spinal cord by postinfection day 5, no virus was detected at any of the time points for the UL38/VP5 recombinant, indicating that the spinal ganglion was a major site of restriction for this recombinant. Taken together, these data indicate that while the UL38/VP5 recombinant is not significantly restricted in replication within the feet, it does not spread efficiently past the spinal ganglia. This restriction could indicate either a defect in spread or a defect in replication within the neurons of the spinal ganglia. Given the decrease in CNS replication that we observed following i.c. inoculation of this recombinant, we chose to evaluate its replication properties in cell lines of neuronal origin.

Replication of the UL38/VP5 recombinant in cells of neuronal origin.

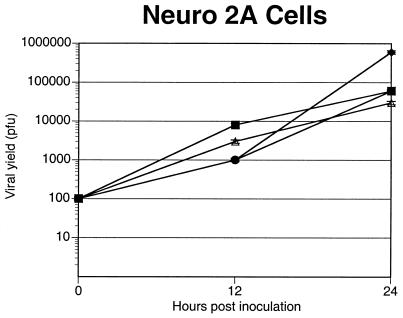

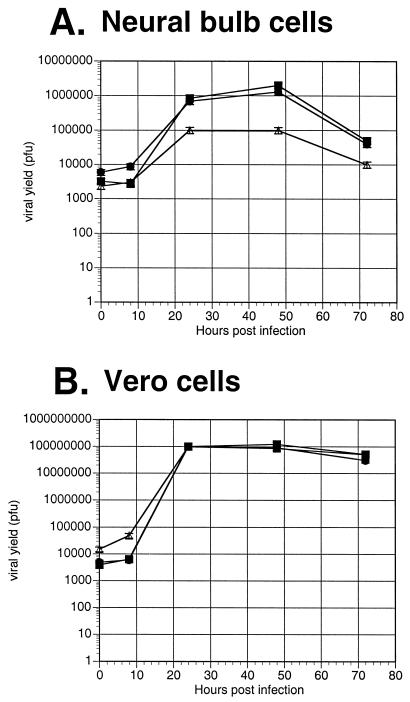

When the recombinants were tested for their ability to replicate on mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2a), no significant differences in yield were observed for the UL38/VP5 recombinant, VP16/VP5, dUTPase/VP5, or VP5 rescued virus recombinants (Fig. 4). Because Neuro-2a cells do not completely mimic all aspects of HSV infection of neurons, we evaluated the UL38/VP5 recombinant's ability to replicate in cultured primary neural bulb cells. By 24 h, the UL38/VP5 recombinant exhibited an approximately eightfold decrease in virus yield on neural bulb cells compared to the dUTPase/VP5 recombinant and the VP5 rescued virus; this trend continued throughout the 72-h time course (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in a parallel growth curve on Vero cells, the UL38/VP5 recombinant showed yields similar to those of the other viral recombinants (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the restriction observed with the UL38/VP5 recombinant on the neural bulb cells is in concordance with the decreased virus yields in spinal ganglia following footpad inoculation, suggesting that this recombinant is restricted in replication specifically within neurons in the mouse.

FIG. 4.

Replication of the promoter substitution recombinants on mouse neuroblastoma cells in vitro. Neuro-2a cells were seeded on six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. The following day, the monolayers were infected with 100 PFU of virus per well. Infected monolayers were harvested at 24 and 48 h and titrated for infectious virus. The results represent the average of two duplicate experiments. Symbols: ▪, VP5 rescue; •, VP16/VP5; ▵, UL38/VP5; ⧫, dUTPase/VP5.

FIG. 5.

Replication of the promoter substitution recombinants on primary neural bulb versus Vero cells in vitro. Primary neural bulb cells (A) or Vero cells (B) were seeded on six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. The following day, the monolayers were infected with 100 PFU of virus per well. Infected monolayers were harvested at 8, 24, 48, and 72 h and titrated for infectious virus. The results represent the average of two duplicate experiments. Symbols: ▪, VP5R; •, UL50/VP5; ▵, UL38/VP5.

DISCUSSION

The restriction in viral replication within neural bulb cells in vitro and within the mouse CNS and spinal ganglia in vivo strongly suggests that the UL38/VP5 recombinant is restricted in replication within neurons and that this restriction is responsible for the observed decrease in neurovirulence. The in vivo replication and rescue data seem to indicate that early expression of VP5 confers a replication advantage in the nervous system. With the exception of replication in primary neural bulb cells, this finding is in contrast to in vitro replication data for all cell lines tested (10).

While the data presented here clearly indicate that the UL38/VP5 recombinant is restricted in replication within the mouse nervous system, strongly suggesting that the primary defect is in replication within neurons, it is impossible to exclude the possibility that the restriction is due in part to a reduced ability of this recombinant to spread throughout the nervous system (neuroinvasion). Clearly, following footpad inoculation, the virus is restricted in its ability to spread past the spinal ganglia. However, because this recombinant is restricted in virus yields following direct CNS inoculation, in vitro infection of neural bulb cells argues that a significant component of its decreased neuroinvasion is due to decreased replication within neurons. In addition, the fact that the virus yields of the UL38/VP5 recombinant were more dramatically reduced in the spinal ganglia than in the CNS (following i.c. inoculation) supports a neuron-specific restriction in replication.

Inoculation of HSV into the CNS by the i.c. route inoculates not only CNS neurons, but also glia and other nonneuronal cells, whereas inoculation of the virus in the periphery (foot) introduces the virus to the nerve termini that transport the virus to the cell bodies in the spinal ganglia. Therefore, the footpad route of infection essentially channels the virus to sensory neurons, and the fact that the UL38/VP5 recombinant was restricted in replication in spinal ganglia by this route is consistent with a neuron-based replication defect (3).

The fact that altering the expression of a structural protein like VP5 could have an impact on neuronal replication is intriguing, but not without precedent. Desai et al. demonstrated that null mutants of VP26, the smallest capsid protein of HSV, exhibit only a twofold reduction in virus yield in cell culture but are restricted 30- to 100-fold in yield within mouse trigeminal ganglia following ocular infection (5). Our observation that altering the kinetics of expression (but not the amount) of VP5 seems to support a more global role for HSV capsid proteins in viral replication within neurons. One could envision that capsid proteins play a role in the efficient trafficking of virion components within cells, and perhaps altering this function has a more pronounced effect on the complex cytological architecture of neurons. Alternatively, it is possible that these capsid proteins play a more important role in the replication of viral DNA than previously realized.

It has recently been demonstrated that mutations within the N terminus of VP5 alter its interaction with scaffold proteins of HSV and that these structures play an important role in the viral replication machinery (19). Again, it may be that altering these structures within neurons has a greater effect than in other cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Indeed, there are a number of examples where altering components of the HSV DNA replication machinery exerts a specific replication restriction in neurons, though the precise basis of this phenomenon is not clear (3, 11).

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this study is that the replication defect exhibited by the UL38/VP5 recombinant seems to be neuron specific. This suggests that there are either neuron-specific elements or fundamental differences in the cellular environment of neurons that impinge on the ability of the UL38/VP5 recombinant to replicate. The fact that the other promoter constructs (and the UL38/VP5 rescuant) replicate to the same levels as the parent HSV strain in neurons argues strongly that the defect is related to a requirement for expression of VP5 at early times, not just at late times.

Our model for this requirement of VP5 at early times draws on the evidence cited above for the interaction of capsid proteins with the HSV replication machinery and the fact that HSV transcription and DNA replication in neurons are generally repressed compared to other cell types. We propose that for HSV to replicate to maximal yields within neurons, gene expression and DNA replication need to be functioning at optimal efficiency. If VP5 is associated with the replication scaffolding, as previously suggested, and plays a role in facilitating efficient replication, it is possible that an absence of this protein prior to DNA replication would result in a more severe restriction in neurons than in other cells. The fact that expression of VP5 by the dUTPase (early) promoter resulted in replication and virulence properties indistinguishable from expression from the native VP5 promoter indicates that early expression of VP5 seems to be a critical factor.

In summary, the results presented here suggest that the leaky-late expression kinetics of VP5 evolved deliberately, and expression of at least some VP5 prior to the onset of viral DNA replication enhances virus yields within the nervous system. It may be that other HSV proteins of the γ1 class have similar roles, and altering their expression kinetics would provide a useful genetic approach to studying the multifactorial bases of viral gene function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants AI06246 (to D.C.B.) and CA11861 (to E.K.W.) from the National Institutes of Health and by a predoctoral fellowship (to P.T.L.) from a Gene Therapy for Cancer training grant from the University of California.

We thank J. O'Neil, N. Kubat, A. Amelio, Z. Zeier, and A. Gussow for critical comments on the manuscript and A. Lewin for helpful suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blair, E. D., and B. W. Snowden. 1991. Comparative analysis of the parameters that regulate expression from promoters of two late HSV-1 gene products, p. 181-206. In E. K. Wagner (ed.), Herpesvirus transcription and its regulation. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 2.Bloom, D. C. 1996. HSV vectors for gene therapy, p. 369-386. In S. M. Brown and A. R. MacLean (ed.), Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 10. Herpes simplex virus protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom, D. C., and J. G. Stevens. 1994. Neuronal specific restriction of an HSV recombinant maps to the UL5 gene. J. Virol. 68:3761-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai, P., N. A. DeLuca, J. C. Glorioso, and S. Person. 1993. Mutations in herpes simplex virus type 1 genes encoding VP5 and VP23 abrogate capsid formation and cleavage of replicated DNA. J. Virol. 67:1357-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai, P., N. A. DeLuca, and S. Person. 1998. Herpes simplex virus type 1 VP26 is not essential for replication in cell culture but influences production of infectious virus in the nervous system of infected mice. Virology 247:115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godowski, P. J., and D. M. Knipe. 1986. Transcriptional control of herpesvirus gene expression: gene functions required for positive and negative regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:256-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imbalzano, A. N., and N. A. DeLuca. 1992. Substitution of a TATA box from a herpes simplex virus late gene in the thymidine kinase promoter alters ICP4 inducibility but not temporal expression. J. Virol. 66:5453-5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane, T. E., A. D. Paoletti, and M. J. Buchmeier. 1997. Disassociation between the in vitro and in vivo effects of nitric oxide on a neurotropic murine coronavirus. J. Virol. 71:2202-2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieu, P. T., N. T. Pande, M. K. Rice, and E. K. Wagner. 1999. The exchange of cognate TATA boxes results in a corresponding promoter strength of two HSV-1 early promoters. Virus Genes 20:5-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieu, P. T., and E. K. Wagner. 2000. The kinetics of VP5 mRNA expression is not critical for viral replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 74:2770-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelosi, E., F. Rozenberg, D. M. Coen, and K. L. Tyler. 1998. A herpes simplex DNA polymerase mutation specifically attenuates neurovirulence in mice. Virology 252:364-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Person, S., and P. Desai. 1998. Capsids are formed in a mutant virus blocked at the maturation site of the UL26 and UL26.5 open reading frames of herpes simplex virus type 1 but are not formed in a null mutant of UL38 (Vp19C). Virology 242:193-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roizman, B., T. Kristie, J. L. McKnight, N. Michael, N. P. Mavromara, and D. Spector. 1988. The trans-activation of herpes simplex virus gene expression: comparison of two factors and their cis sites. Biochimie 70:1031-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryder, E. F., E. Y. Snyder, and C. L. Cepko. 1990. Establishment and characterization of multipotent neural stem cell lines using retrovirus vector-mediated oncogene transfer. J. Neurobiol. 21:356-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandri-Goldin, R. M., A. L. Goldin, L. E. Holland, J. C. Glorioso, and M. Levine. 1983. Expression of herpes simplex virus beta and gamma genes integrated in mammalian cells and their induction by an alpha gene product. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:2028-2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steffy, K. R., and J. P. Weir. 1991. Mutational analysis of two herpes simplex virus type 1 late promoters. J. Virol. 65:6454-6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner, E. K., J. F. Guzowski, and J. Singh. 1995. Transcription of the herpes simplex virus genome during the productive and latent infections, p. 123-168. In W. E. Cohen and K. Moldave (ed.), Progress in nucleic acid research and molecular biology. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Warner, S., G. Chytrova, P. Desai, and S. Person. 2001. Mutations within the N terminus of VP5 alter its interaction with the scaffold proteins of herpes simplex virus type 1. Virology 284:308-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinheimer, S. P., and S. L. McKnight. 1987. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional controls establish the cascade of herpes simplex virus protein synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 195:819-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]