Abstract

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) entry requires the interaction between the envelope glycoprotein D (gD) and a cellular receptor such as nectin-1 (also named herpesvirus entry mediator C [HveC]) or HveA/HVEM. Nectin-1 is a cell adhesion molecule found at adherens junctions associated with the cytoplasmic actin-binding protein afadin. Nectin-1 can act as its own ligand in a homotypic interaction to bridge cells together. We used a cell aggregation assay to map an adhesive functional site on nectin-1 and identify the effects of gD binding and HSV early infection on nectin-1 function. Soluble forms of nectin-1 and anti-nectin-1 monoclonal antibodies were used to map a functional adhesive site within the first immunoglobulin-like domain (V domain) of nectin-1. This domain also contains the gD-binding site, which appeared to overlap the adhesive site. Thus, soluble forms of gD were able to prevent nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation and to disrupt cell clumps in an affinity-dependent manner. HSV also prevented nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation by occupying the receptor. Early in infection, nectin-1 was not downregulated from the cell surface. Rather, detection of nectin-1 changed gradually over a 30-min period of infection, as reflected by a decrease in the CK41 epitope and an increase in the CK35 epitope. The level of detection of virion gD on the cell surface increased within 5 min of infection in a receptor-dependent manner. These observations suggest that cell surface nectin-1 and gD may undergo conformational changes during HSV entry as part of an evolving interaction between the viral envelope and the cell plasma membrane.

The interaction between herpes simplex virus (HSV) envelope glycoprotein D (gD) and a specific cellular receptor is required for virus entry into mammalian cells (2, 48). This essential step follows an initial attachment mediated by HSV gC and gB bound to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (17, 18, 56). In addition, fusion of the envelope with the cell plasma membrane involves gB and the gH/gL complex (36, 50, 55).

Receptors for gD belong to at least three unrelated families. The herpesvirus entry mediator A (HveA; also called HVEM and TNFRSF14) belongs to the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF) receptor family and mediates entry of most HSV-1 and HSV-2 strains (34, 53). Nectin-1 (HveC; also called PRR1 and CD111) (14, 26) and nectin-2 (HveB; also called PRR2 and CD112) (11, 51) are members of the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily. Nectin-1 allows entry of all the HSV-1 and HSV-2 strains tested as well as pseudorabies virus and bovine herpesvirus type 1 (9, 14, 32). In contrast, nectin-2 can be used only by HSV-2, some laboratory strains of HSV-1 (rid1 and ANG), and pseudorabies virus (25, 51). The related poliovirus receptor (PVR) CD155 does not function as an HSV receptor, but can be used by pseudorabies virus and bovine herpesvirus type 1 (14). Lastly, a specific type of heparan sulfate modified by d-glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase 3 can substitute for HveA or nectin-1 and binds to gD to allow entry of HSV-1 into cells (45).

Direct binding of gD to these receptors correlates with their usage by the corresponding herpesvirus strains (9, 14, 21, 32, 34, 53). The structure of the gD/HveA complex at the atomic level shows that the binding area on gD is limited to an N-terminal loop which contacts the first two cysteine-rich repeats of HveA (3). The sites involved in nectin-1 binding are not accurately known, but several pieces of data showed that the HveA and nectin-1 binding sites on gD differ but overlap (14, 21, 38). The V domain of nectin-1 (the N-terminal Ig-like domain) alone can mediate entry of HSV, although with reduced efficacy, and binds to soluble gD with full affinity (6, 22). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) competition studies showed that a region between amino acids 83 and 104 on the V domain is involved in gD binding (20), and recent studies of amino acid substitutions in nectin-1 additionally identified a region between amino acids 67 and 76 (5).

The nectin family consists of proteins related in sequence and structure to PVR (nectin-2/HveB, nectin-1/HveC, and nectin-3). They have the same Ig-like domain structures (one V domain followed by two C2 domains) (11, 26, 29, 40, 43). Nectin-1 and nectin-2 appear to be expressed by a broad range of tissues and cells (7, 14, 51). Nectins 1, 2, and 3 are found at adherens junctions (AJ), where they act as adhesion molecules (1, 43, 49). Various isotypes of the nectins that are generated by alternative splicing have the same ectodomain linked to different transmembrane regions and cytoplasmic tails (7, 11, 14, 26, 35, 40, 43). One isotype of nectin-1 as well as nectin-2 and nectin-3 contain an afadin/AF-6 binding site at the C terminus (40, 43, 49). This site binds to a PDZ domain of afadin, an F-actin-binding protein (49), which is also a phosphorylation target for the Ras protein (23) and Eph tyrosine kinase receptors (39). Although the non-afadin-binding isoform of nectin-1 can mediate entry of free HSV particles into cells (7), the presentation of nectin-1 at AJ mediated by afadin binding is required for efficient spread of HSV from cell to cell (42).

Nectin-1/HveC and nectin-2/HveB act as their own ligands and do not bind each other, but nectin-3 can bind all three nectins to promote cell adhesion (1, 43, 49). Nectins are found as dimers on the cell surface (cis-dimerization), which then bind to dimers on an adjacent cell (trans-dimerization) to form a tetrameric complex (1, 33, 42, 43, 49). Consistent with that, the soluble ectodomain of nectin-1 [previously named HveC(346t)] was shown to be a tetramer in solution (21). In contrast, truncated forms containing the first two Ig-like domains or the V domain alone [previously named HveC(245t) and HveC(143t), respectively] formed soluble dimers (22). We observed that binding of the gD ectodomain to HveC(346t) disrupted tetramers into dimers (21) and suggested that gD might interfere with nectin-1 cellular function. A recent study by Sakisaka et al. (42) showed that gD and HSV binding to the cell surface prevented nectin-1 from mediating cell aggregation by inhibiting nectin-1 trans- but not cis-dimerization.

Here we investigate further the effects of HSV and gD on cell surface nectin-1 by monitoring the ability of nectin-1 to mediate cell aggregation. Using truncated forms of nectin-1 and anti-nectin-1 MAbs, we determined that the functional adhesive site overlapped but differed from the gD binding site within the V domain. Our results also indicate that early in infection, nectin-1 remains on the cell surface despite the disappearance of certain epitopes due to gD occupancy. Simultaneously, an epitope of the receptor became more accessible, suggesting active changes affecting the conformation of nectin-1. In addition, we noticed a rapid increase in gD staining on cells expressing nectin-1 but not on control cells. This enhanced staining of gD appeared to occur in the absence of attachment of new virus particles on the cell surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, antibodies, and recombinant proteins. (i) Cells.

B78H1-C10 cells and B78H1-Control-16 cells, abbreviated here as C10 and Control-16 cells, respectively, were derived from B78H1 murine melanoma cells (15) by transfection with pBG38 expressing human nectin-1 (14) and the empty vector pcDNA3, respectively; G418 at 500 μg/ml was used for the selection of clone C10, which stably expresses nectin-1 (L. Kwan and P. G. Spear, unpublished data). These cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 5% fetal calf serum and G418 at 500 μg/ml. They were used previously in vivo and briefly described by Miller et al. (31).

(ii) Virus.

HSV-1 KOS was grown and titered on Vero cells and purified as described (16).

(iii) Antibodies.

Anti-nectin-1 MAbs CK6 and CK8 detect linear epitopes in the V domain between amino acids 83 and 104. CK41 detects a conformational epitope in the V domain which overlaps the CK6 and CK8 epitopes; CK35 detects a conformational epitope requiring the presence of the first C domain (20). Anti-HveA MAb CW3 detects a conformational epitope of human HveA/HVEM (52).

For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and immunofluorescence, CK41, CK35, and anti-gD MAb DL2 (8) were directly labeled with Oregon green (OG) using the Fluoreporter Oregon green 488 protein labeling kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). CK41 was also labeled with phycoerythrin (PE) at Molecular Probes. The antiafadin antibody (anti-AF6) was purchased from Becton Dickinson Transduction Laboratories.

(iv) Proteins.

Soluble forms of gD [gD(306t), gD(285t), and gD(rid1t)] were purified from recombinant baculovirus-infected cell supernatants as described earlier (37, 41, 46). A similar strategy was used to produce and purify soluble forms of nectin-1 [HveC(346t), HveC(245t), and HveC(143t)] and nectin-2 [HveB(361t)] (21, 22). In the present report, we have used the recent nectin nomenclature; however, for consistency, we will keep the HveC/B nomenclature for published reagents such as the recombinant truncated receptors.

Immunofluorescence assay.

C10 and Control-16 cells were seeded on glass cover slips and grown overnight. Cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature (RT), followed by quenching of the remaining paraformaldehyde by incubation in 50 mM NH4Cl for 10 min at RT and permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at RT (adapted from Sodeik et al. [47]). Fixed cells were incubated in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 10% normal goat serum for 30 min at RT and then labeled with anti-AF6 (afadin) antibody followed by Alexa Fluor594-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) and then by OG-CK41 antibody (anti-nectin-1). All incubations were performed in PBS with 10% normal goat serum for 30 min at RT with 1 μg of purified IgG per ml. The cover slips were rinsed three times with PBS and once with H2O and mounted in ProLong Antifade (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Preparations were examined with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope or a Nikon TE-300 inverted microscope coupled to a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000-MP confocal imaging system. A two-line argon-krypton laser emitting at 488 nm and 568 nm was used to excite fluorescence of OG and Alexa Fluor 594. Typically a 60×, 1.4 NA oil immersion objective lens was used for confocal microscopy.

Aggregation assay.

Cells were trypsinized to ensure complete separation, counted, washed, and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml in cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) in the absence of calcium and magnesium ions.

(i) Kinetic experiments.

For kinetic experiments, cells were incubated on ice at RT or at 37°C in a CO2 incubator in a volume of 400 μl in polystyrene tubes (Falcon 2054). Cells were gently agitated every 15 min during the incubation to prevent attachment to the tube and then were fixed by the addition of glutaraldehyde (stock 25%) to a final concentration of 2%. Fixed cells and clumps were stored at 4°C and counted within 24 h. Cells were observed and counted using a Nikon TMS microscope. The trypan blue dye exclusion assay on nonfixed cells showed no significant cell death during the aggregation and inhibition assays reported in this study. Data are reported as At = (Nt/N0) × 100, where Nt and N0 represent the number of independent entities (clumps and individual cells) at incubation times t and 0, respectively. According to this formula, the more aggregation, the lower the Nt value and therefore the lower the At (aggregation index) percentage.

(ii) Inhibition experiments.

For inhibition experiments, cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were mixed with the given inhibitor on ice for 1 h prior to incubation at 37°C for 80 to 90 min as described above. Aliquots of cells were fixed either before (time zero) or after incubation at 37°C. Inhibition was reported as [(Atinh − At)/(AtControl-16 − At)] × 100, where Atinh and At represent aggregation of C10 cells in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively, and AtControl-16 represents the nonspecific aggregation of Control-16 cells.

(iii) Disruption assays.

For disruption assays, C10 and Control-16 cells were subjected to an aggregation assay as described above for 60 min at 37°C. Then soluble gD or bovine serum albumin (BSA) was added to the desired concentration and mixed with cells carefully in order not to disrupt aggregates. Cells were fixed (time zero) or incubated further at 37°C for 15, 30, 60, or 90 min and then fixed. Data are represented as (Nt/N−60) × 100, where Nt and N−60 are the total number of entities (clumps and/or single cells) observed at time t after the addition of soluble protein and at time −60 min (i.e., prior to clump formation), respectively.

Flow cytometry. (i) Nectin-1 expression.

Cells were detached with 0.02% (wt/vol) disodium EDTA in PBS (Versene; Gibco-BRL). Aliquots of 3 × 105 cells were stained on ice for 1 h with anti-nectin-1 MAb CK41 (5 μg/ml) in 100 μl of PBS containing 3% fetal calf serum (PBS-FCS), washed with PBS-FCS, and incubated with goat anti-mouse Ig-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) in PBS-FCS. After a PBS wash, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS.

(ii) Detection of nectin-1 and gD epitopes after infection.

Cells were trypsinized and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in HBSS (no Ca2+, no Mg2+). They were incubated on ice for 60 min in the presence or absence of HSV-1 KOS at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 PFU/cell. Virus-containing HBSS was removed, and cells were washed once with cold HBSS and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in warm HBSS. Cells were then placed at 37°C in a water bath for 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, or 60 min, put back on ice for 5 min to stop infection and clumping, and immediately washed once with cold PBS-FCS. Cells were then resuspended in PBS-FCS at 6 × 106 cells/ml (clumps being disrupted prior to staining) and maintained on ice until all samples were processed. Cells were then incubated on ice with fluorescent MAb PE-CK41 (5 μg/ml), OG-CK35 (25 μg/ml), or OG-DL2 (25 μg/ml) diluted in PBS-FCS for 1 h. For control samples, MAb was omitted. Cells were finally washed with PBS-FCS and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS-FCS.

RESULTS

Expression of nectin-1 in B78H1 cells.

Mouse melanoma B78H1 cells are resistant to wild-type HSV infection because they do not express any functional HSV receptors (i.e., murine HveA or murine nectin-1) (31; Kwan et al., unpublished data). B78H1 cells transfected with the human nectin-1 expression plasmid are named B78H1-C10 (C10 cells for short), and cells transfected with the empty vector are named B78H1-Control-16 (Control-16). C10 cells are fully permissive for HSV infection and produce progeny virions (31; Kwan et al., unpublished data).

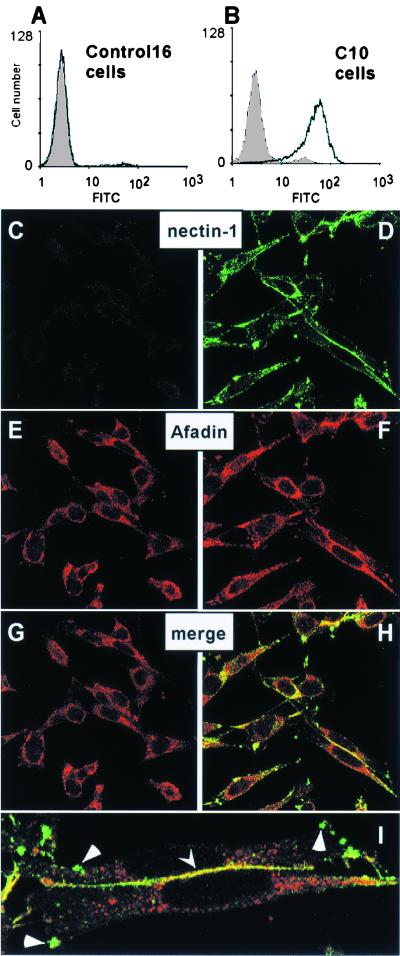

Surface expression of nectin-1 by the permissive C10 cells was demonstrated by FACS (Fig. 1A and B). Immunofluorescence studies of these cells showed that nectin-1 was found at cell-cell contact areas (Fig. 1D). Nectin-1 not engaged in cell contacts was found unevenly distributed on the cell surface either on small protrusions or on longer filaments (Fig. 1D and I).

FIG. 1.

Expression of nectin-1 in B78H1-C10 cells detected by FACS and confocal microscopy. Control-16 cells (A) and C10 cells (B) were stained with anti-nectin-1 MAb CK41 (black line). The gray shading represents fluorescence of cells in the absence of CK41 but after incubation with the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse Ig-FITC). Permeabilized Control-16 cells (C, E, and G) and C10 cells (D, F, H, and I) were stained for expression of nectin-1 (C and D) and afadin (E and F). Merged images of the staining are shown in G, H, and I (as a magnification of panel H). Yellow indicates colocalization of nectin-1 and afadin at cell junctions (indicated by arrowhead). Triangles point to clusters of free nectin-1 on the cell surface. Staining of nonpermeabilized cells with anti-nectin-1 MAb CK41 showed similar distribution of nectin-1 (data not shown).

The C terminus of the nectin-1 cytoplasmic tail contains an afadin-binding site (49). Afadin was randomly distributed in the cytoplasm of nectin-1-deficient Control-16 cells without particular localization at cell contacts (Fig. 1E). However, in C10 cells, afadin was detected both in the cytoplasm and at cell contacts, where it colocalized with nectin-1 (Fig. 1F, H, and I) in a similar way as described previously in transfected L cells (42). Since human and murine nectin-1 are highly conserved and retain an identical afadin-binding site (30, 44), it was not surprising to detect an interaction between human nectin-1 and murine afadin. Interestingly, nectin-1 associated with afadin predominantly at cell junctions, whereas most nectin-1 clustered elsewhere on the cell surface did not colocalize with afadin (Fig. 1H and I).

Since the C10 cells appear to contain nectin-1 and afadin at cell junctions and since nectin-1 is the only HSV receptor on these cells, they provide a valuable tool to study the cellular functions of nectin-1 in the absence and presence of HSV infection. Accordingly, we used these cells to identify the functional site(s) of nectin-1 and determine the effects of HSV infection on nectin-1 structure and function.

Nectin-1 mediates aggregation of B78H1-C10 cells.

The cell-cell adhesion activity of nectin-1 and other nectins present at AJ was shown to correlate with the ability of these adhesion molecules to induce single transfected L cells in suspension to aggregate (33, 49). However, L cells express endogenous HSV receptors that might interfere with studies of HSV entry mediated by nectin-1. In order to determine first if nectin-1 can mediate cell aggregation in the B78H1 model, C10 and Control-16 cells were subjected to an aggregation assay modified from the technique described by Aoki et al. (1). Cells were detached with trypsin (trypsinization did not affect the amount of nectin-1 on the surface of C10 cells as detected by FACS; C. Krummenacher and F. Baribaud, unpublished observation) and resuspended as a single-cell suspension in HBSS in the absence of Mg2+ and Ca2+.

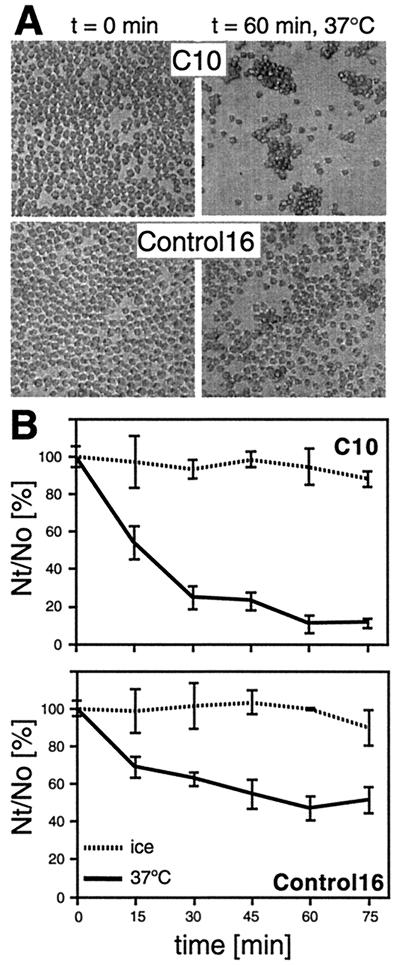

After incubation at 37°C, C10 cells expressing nectin-1 formed large aggregates, whereas Control-16 cells did not (Fig. 2A). This phenomenon was monitored over time at various temperatures (Fig. 2B). C10 cells aggregated rapidly at 37°C, more slowly at room temperature (not shown), and not at all when cells were left on ice, suggesting that nectin-1 mediated aggregation in an active and dynamic fashion. Control-16 cells developed fewer and significantly smaller clumps at 37°C, as shown in Fig. 2A, lower right panel. Other adhesion molecules expressed by the parental cell line B78H1 probably account for this nectin-1-independent cell aggregation (24). The nectin-1-independent aggregation of C10 and Control-16 cells was predominant when Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations were present, probably because of the more intense use of other cell adhesion molecules (data not shown). By contrast, nectin-1-specific aggregation of C10 cells occurred during incubation in PBS containing 0.02% EDTA (Versene; Gibco-BRL) (data not shown), confirming that neither calcium nor magnesium was necessary for nectin-1-dependent aggregation (49). In agreement with reported data on transfected L cells (43), nectin-1 mediated the aggregation of C10 cells by homophilic interactions, since C10 cells did not coaggregate efficiently with Control-16 cells (data not shown). The very small number of Control-16 cells aggregated together with C10 cells reflects the limited adhesive potential of nectin-1-negative cells under these conditions.

FIG. 2.

Nectin-1-mediated aggregation of C10 cells. Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in HBSS as a single-cell suspension. They were incubated at 37°C or on ice for various periods of time and fixed with glutaraldehyde. (A) C10 cells (top) and Control-16 cells (bottom) fixed after 0 and 60 min at 37°C. (B) Aggregation over time. Cells were observed under a microscope and scored as Nt/N0 × 100, where Nt and N0 are the total number of entities (clumps or single cells) observed at times t and 0 min, respectively. Values are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of a triplicate representative experiment. A value of 100 represents no aggregation; the lower the value, the more aggregation.

We used this aggregation assay (i) to map the portions of nectin-1 required to mediate cell adhesion and (ii) to study the effects of gD and HSV on nectin-1-mediated aggregation.

Mapping the adhesive site on the nectin-1 V domain.

Glycoprotein D binds to the V domain of nectin-1 (6, 22) and might occupy or overlap a functional site, thereby interfering with nectin-1 adhesive activity (trans-dimerization), as proposed previously (21, 42). Here we analyzed the involvement of the nectin-1 V domain in nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation. Since cell-bound nectin-1 acts as its own ligand in a homotypic interaction to bridge cells together (43), we reasoned that the soluble nectin-1 ectodomain might prevent this interaction and thus impair cell aggregation.

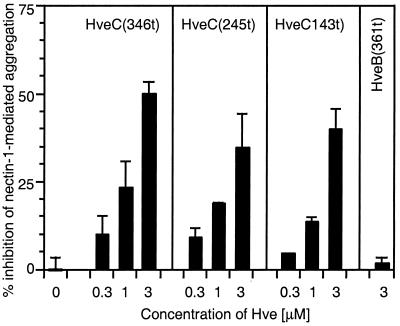

Three forms of soluble receptor were tested to mimic ligand binding to cell surface nectin-1: HveC(346t), consisting of the full extracellular domain of nectin-1; HveC(245t), containing the first two Ig-like domains; and HveC(143t), containing only the most distal Ig-like domain (or V domain) (21, 22). All three soluble forms of nectin-1 interfered with cell aggregation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). The fact that the soluble V domain by itself was able to prevent cell aggregation indicates that this domain is directly involved in nectin-1 trans-dimerization.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of nectin-1-mediated aggregation using soluble truncated forms of nectin-1. C10 cells or Control-16 cells were detached and resuspended in cold HBSS. C10 cells were incubated on ice for 60 min in the presence or absence of various concentrations of soluble forms of nectin-1 [HveC(346t), HveC(245t), or HveC(143t)] prior to a 90-min incubation at 37°C. Soluble nectin-2 form [HveB(361t)] was used as a negative control. Solid bars represent the percent inhibition of nectin-1-mediated specific aggregation of C10 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble nectin forms. A value of 100% inhibition indicates that aggregation of C10 cells was similar to aggregation of Control-16 cells, used as a background control. A value of 0 indicates the absence of inhibition. Values are the mean ± SD of a triplicate representative experiment.

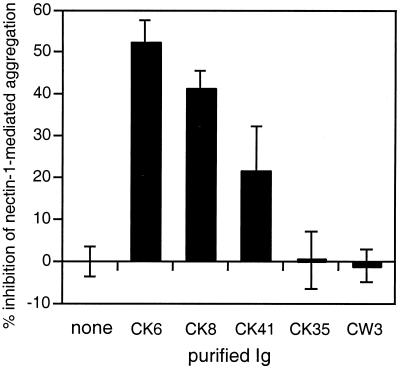

To refine the localization of the functional site of nectin-1 within the V domain, we used anti-nectin-1 MAbs as potential inhibitors of cell aggregation. MAbs CK6, CK8, CK35, and CK41 all detected nectin-1 on the surface of C10 cells by flow cytometry (Fig. 1B and data not shown). CK6, CK8, and CK41 detect overlapping epitopes within the V domain of nectin-1 (20). The CK6 and CK8 linear epitopes are located between amino acids 80 and 104. These two MAbs compete with CK41, which detects a conformational epitope. CK35 recognizes a conformational epitope outside the V domain and does not interfere with gD binding or HSV infection. In contrast, CK6, CK8, and CK41 are able to block HSV entry, CK41 being the most effective in this regard (20). These three MAbs were all able to interfere with nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation (Fig. 4). However, in contrast to their effects on HSV entry, CK6 and CK8 were more efficient than CK41. MAb CK35 had no effect on nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation. Altogether, these data suggest that the regions of the V domain of nectin-1 involved in cell adhesion and in gD binding may overlap but are different.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of nectin-1-mediated aggregation using anti-nectin-1 MAbs. C10 cells or Control-16 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in cold HBSS. C10 were incubated on ice for 60 min in the presence or absence of 300 μg of purified anti-nectin-1 Ig per ml prior to a 90-min incubation at 37°C. Solid bars represent the percent inhibition of nectin-1-mediated specific aggregation of C10 cells in the presence of purified Ig. Fabs from CK6 and CK41 had the same effect as the complete Ig (not shown). CW3 is an anti-HveA MAb used as a negative control (52). A value of 100% inhibition indicates that aggregation of C10 cells was similar to aggregation of Control-16 cells. A value of 0 indicates the absence of inhibition. Values are the mean ± SD of a triplicate representative experiment.

gD binding interferes with nectin-1-mediated cell adhesion.

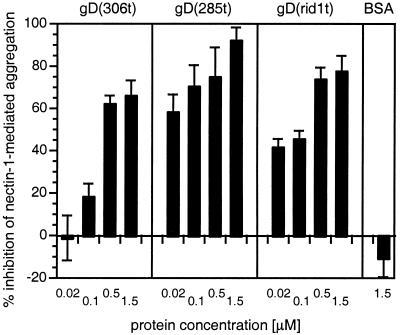

A recent report by Sakisaka et al. (42) described the effect of a soluble form of gD-Fc fusion protein on aggregation of transfected L cells expressing nectin-1. In a similar experiment, we tested the ability of several previously characterized soluble forms of gD to prevent C10 cell aggregation (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of nectin-1-mediated aggregation using soluble truncated forms of gD. C10 cells or Control-16 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in cold HBSS. C10 cells were incubated on ice for 60 min in the presence or absence of various concentrations of gD(306t), gD(rid1t), gD(285t), or BSA prior to an 80-min incubation at 37°C. Solid bars represent percent inhibition of nectin-1-mediated specific aggregation of C10 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble forms of gD. A value of 100% inhibition indicates that aggregation of C10 cells was similar to aggregation of Control-16 cells. A value of 0 indicates the absence of inhibition. Values are the mean ± SD of a triplicate representative experiment.

Soluble gD(306t) contains the ectodomain of HSV-1 KOS gD from amino acids 1 to 306 and is considered wild type. Its affinity constant (KD) for soluble nectin-1 is 3.2 μM (22). A shorter form of the same protein, gD(285t), truncated at position 285, lacks functional region 4 (4), which results in a 100-fold higher affinity for nectin-1 (KD = 38 nM). gD(rid1t) is a soluble form of gD truncated at position 306 derived from HSV-1 rid1, which carries a single point mutation at position 27 (Gln to Pro) compared to gD KOS (10, 37). gD(rid1t) binds nectin-1 with a 10-fold higher affinity (KD = 0.17 μM) than the equivalent gD(306t) from the KOS strain (22).

All three forms of gD were able to prevent aggregation of nectin-1, although with different efficiencies, whereas BSA, used as control, had no effect (Fig. 5). gD(285t) was able to completely prevent aggregation, whereas the other forms, gD(306t) and gD(rid1t), inhibited aggregation to a maximum of 70 and 80%, respectively, even at high concentrations. The efficiency of inhibition as well as the concentration of each form of gD required to achieve 40 to 60% inhibition correlated with the relative affinities of soluble gD forms for nectin-1.

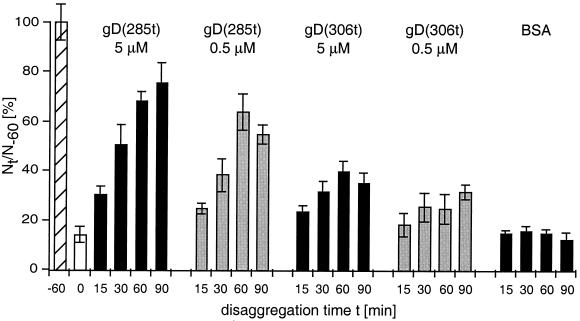

gD binding disrupts nectin-1-mediated cell adhesion.

The observation that gD was able to prevent nectin-1 from performing its adhesive function prompted us to ask if gD could bind to and dissociate nectin-1 when it is already engaged in cell-cell contact. In this experiment, C10 cell aggregates are formed first and then soluble gD is added. The cell population is monitored over time for disaggregation after the addition of gD (Fig. 6). The high-affinity form, gD(285t), disrupted C10 cell clumps very efficiently at both high and low concentration. In comparison, gD(306t) had a limited effect, even at higher concentrations, and the control (BSA) had no effect. Addition of either form of gD did not reverse the course of nectin-1-independent aggregation of Control-16 cells (not shown). These data suggest that gD could bind to nectin-1 when it was engaged in cell contacts to disrupt the trans-interaction between nectin-1 dimers; however, only gD with a high affinity could displace enough nectin-1 molecules to disrupt cell aggregates.

FIG. 6.

Disruption of nectin-1-mediated aggregates by soluble gD. C10 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in HBSS. They were incubated at 37°C for 60 min to allow aggregates to form, then soluble gD or BSA was added, and incubation at 37°C proceeded for the indicated period of time. Aggregation of C10 cells at the time of gD or BSA addition (t = 0) is shown as an open bar. Cells were scored as Nt/N−60 × 100, where Nt and N−60 are the total number of entities (clumps and/or single cells) observed at time t after the addition of soluble protein and at time −60 min (i.e., prior to clump formation), respectively. Values are the mean ± SD of a triplicate representative experiment. A value of 100 represents nonaggregated cells at t−60 (hatched bar).

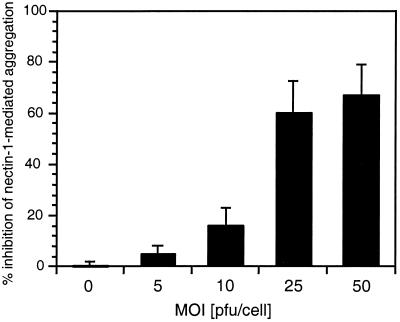

HSV can prevent aggregation of C10 cells.

Since soluble gD was able to bind cell surface nectin-1 and prevent its adhesive function, it was of interest to test whether HSV could accomplish the same effect in this assay. Sakisaka et al. (42) used a similar assay on transfected L cells to find a partial effect on preventing aggregation. We incubated C10 and Control-16 cells with various amounts of HSV-1 KOS for 1 h on ice to allow virus to attach. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 90 min to allow clumping to occur.

HSV was able to prevent aggregation in a multiplicity-dependent fashion (Fig. 7). Virus had no effects on the nonspecific clumping of control Control-16 cells (not shown). Under the conditions of this experiment, virus entry and infection can take place simultaneously with aggregation. Infection was reflected by cytopathic effects (CPE) observed on C10 cells but not Control-16 cells after 90 min (data not shown). The level of CPE correlated with the MOI. When HSV particles were tested for their ability to disrupt existing cell clumps (as shown for soluble gD in Fig. 6), no significant dissociation was observed even at a high MOI within 90 min (data not shown). This might be due to an insufficient amount of virus, the inability to reach cell junctions where active nectin-1 was sequestered due to particle size, a low affinity of virion gD for nectin-1 [similar to gD(306t)], or to the adhesive properties of HSV binding to heparan sulfate, thus attaching cells together.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of nectin-1-mediated aggregation using infectious HSV particles. C10 cells or Control-16 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in cold HBSS. Cells were incubated on ice for 60 min in the absence or presence of an increasing number of virus particles. Bars represent the percent inhibition of nectin-1-mediated specific aggregation of C10 cells in the presence of increasing amounts of HSV. A value of 100% inhibition indicates that aggregation of C10 cells was similar to aggregation of Control-16 cells. A value of 0 indicates the absence of inhibition. Values are the means ± SD of a triplicate representative experiment.

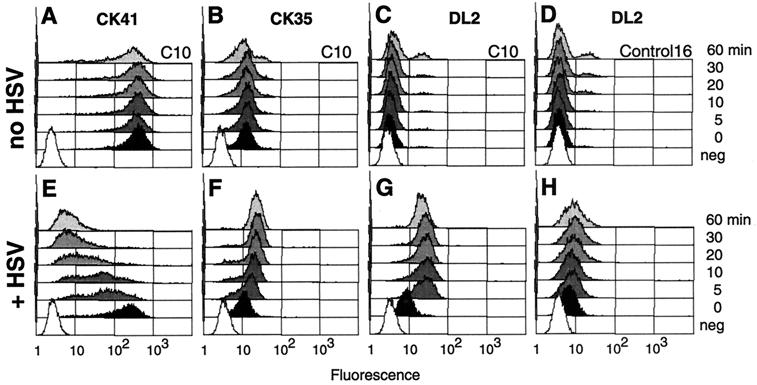

Effects of HSV on cell surface nectin-1.

To understand the mechanism by which HSV inhibits the adhesive function of nectin-1, we further analyzed the effects of the early steps of HSV infection on cell surface nectin-1. Anti-nectin-1 MAbs were used to detect nectin-1 epitopes on C10 cells by FACS under the conditions used in the aggregation assay with doses of HSV that prevented cell aggregation. C10 cells were incubated with or without HSV (MOI = 50) for 1 h on ice and then incubated in a water bath at 37°C. After various incubation times, cells were placed back on ice to stop infection and stained with anti-nectin-1 MAbs.

The anti-V domain MAb CK41 stained C10 cells intensely after cells were incubated on ice (time zero) in the absence or presence of HSV (Fig. 8A and E). The Control-16 cells remained negative because they do not express nectin-1 (not shown). A significant amount of virion gD was also detected on cold C10 cells exposed to virus (Fig. 8G), the presence of which only slightly affected the intensity of detection of the CK41 epitope. However, after placing the infected cells at 37°C, the CK41 epitope rapidly became inaccessible (Fig. 8E). By 30 min after infection, CK41 staining was considerably diminished, and a number of cells were negative. In contrast, the CK41 epitope remained accessible on C10 cells incubated under the same conditions in the absence of virus (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Detection of nectin-1 and gD on cell surface early in infection. C10 cells were incubated on ice without (A, B, and C) or with (E, F, and G) HSV-1 KOS particles at an MOI of 50 PFU/cell. Similarly, Control-16 cells were incubated on ice for 60 min in the absence (D) or presence (H) of HSV. Cells were then placed at 37°C for 0 (black) or 5, 10, 20, 30, or 60 min (gray) and then immediately placed back on ice and stained. White (neg) represents background autofluorescence of cells in the absence of antibody. Cells were stained with anti-nectin-1 MAbs PE-CK41 (A and E) and OG-CK35 (B and F) or with anti-gD MAb OG-DL2 (C, D, G, and H). Fluorescence of PE-CK41 was read in the FL-2 channel, whereas the other samples were read in the FL-1 channel. Histograms are from a representative experiment.

The CK41 epitope overlaps the gD binding site on nectin-1 (20), which may explain its disappearance from the cell surface under these conditions. Since we had MAbs to other parts of nectin-1, we asked whether this receptor was still expressed on the cell surface or was taken into the cell or modified. We used the anti-nectin-1 MAb CK35, which does not interfere with gD binding to nectin-1. Contrary to CK41, the staining intensity of CK35 increased with time in the presence of virus (Fig. 8F), whereas it did not change with time on noninfected C10 cells (Fig. 8B). The CK35 data suggest that nectin-1 was not removed from the cell surface but was modified during the early stage of HSV infection. Changes affecting nectin-1 conformation reached their maximum after 30 min, and no further significant changes were noted between 30 and 60 min of infection.

When C10 or Control-16 cells were exposed to HSV on ice, similar amounts of gD were detected with MAb DL2 (Fig. 8G and H). Interestingly, the detection of gD increased dramatically when infected C10 cells were placed at 37°C for 5 min (Fig. 8G) but then remained unchanged even with prolonged incubation times at 37°C. This increase was observed when unbound remaining virus was removed and cells were washed prior to incubation at 37°C. Therefore, the increased gD staining cannot be explained by the binding of additional virus particles during the incubation at 37°C. In addition, this increase in gD signal depended on the expression of nectin-1, since the level of gD detection remained the same on Control-16 cells exposed to virus and then left on ice or incubated at 37°C (Fig. 8H). It indicated that no additional virus attached to the cells in a nectin-1-independent manner. This suggests an evolving interaction between the viral envelope and the cell plasma membrane involving nectin-1 and gD.

DISCUSSION

The expression of nectin-1 as a cell surface molecule involved in cell junctions raised the question of its use by free HSV particles or for direct cell-cell spread (28, 54). In order to study the ability of gD to bind to free receptors on the cell surface and to receptors involved in AJ, we used a new system of stably transfected cells expressing human nectin-1 as the sole receptor for HSV. These cells (B78H1-C10) expressed large amounts of surface nectin-1, which was mainly located at cell junctions in association with afadin/AF-6. Interestingly, free nectin-1 was also seen as clusters on the cell surface outside of junctions, and in this case, the majority of nectin-1 did not appear to be associated with afadin. It is not clear whether afadin is recruited only after nectin-1 is engaged in contacts or if it is a prerequisite for nectin-1's being stably retained at cell junctions. Targeting or stabilizing of nectin-1 by afadin at cell contacts was shown to be required for efficient plaque formation by HSV in L cell monolayers but not for entry of free virus particles (42).

Effects of gD binding to the nectin-1 V domain on cell aggregation.

Sakisaka et al. (42) showed that binding of gD to the surface of transfected L cells prevented aggregation, probably because it interacted directly with a functional site of nectin-1. In addition to confirming this study using a melanoma cell line, which does not express endogenous murine nectin-1, we showed that a high affinity of gD for nectin-1 was more efficient at preventing aggregation. The high-affinity form gD(285t) was the only one to bind nectin-1 tightly enough to completely prevent aggregation. Soluble gD forms with a lower affinity, gD(306t) and gD(rid1t), could only block about 70 and 80% of the aggregation, respectively, even when present at a high concentration. It is possible that trans-dimerization of cell surface nectin-1 is cooperative and therefore is favored over interaction between cell surface nectin-1 and the lower-affinity forms of soluble gD.

We also demonstrated that gD was able to disrupt preformed cell aggregates. The affinity of nectin-1 for itself in a cis- or trans-interaction is not known. The trans affinity might not be as high as the gD(285t)/nectin-1 interaction (KD = 10−8 M), since soluble gD(285t) could disrupt cell clumps, presumably by displacing nectin-1 involved in cell-cell contacts (Fig. 6). gD(306t) has a 100-fold-lower affinity for nectin-1 and showed a more limited ability to disrupt aggregates. Therefore, we speculate that the affinity of the nectin-1-nectin-1 trans-interaction might be approximately 10−6 to 10−7 M. The affinity of virion gD for nectin-1 is unknown. However, even a lower-affinity form of virion-bound gD [i.e., with a KD similar to that of gD(306t)] may be an effective ligand, since a limited number of nectin-1-gD interactions should be sufficient to allow entry.

The complete gD binding site was shown to be located within the nectin-1 V domain (6, 22), and soluble gD prevented trans-dimerization of nectin-1 but not cis-dimerization (42). In addition to verifying these results, we showed here that gD was able to dissociate cell aggregates mediated by nectin-1 trans-dimers. These results correlate with our earlier observations that soluble gD(285t) was able to disrupt a soluble nectin-1 ectodomain tetramer (resulting from cis- and trans-dimerization) but apparently not a soluble nectin-1 V domain dimer (cis-dimer) (21, 22). This suggests that the V domain of nectin-1 may be involved in both cis- and trans-dimerization.

It is important to note that although (i) gD binding to the V domain prevented aggregation and (ii) soluble V domain alone prevented aggregation, these observations do not show that the V domain necessarily interacts with itself in trans. Rather, the V domain of one nectin-1 molecule may contact any domain on the opposite nectin-1 dimer. The third domain is a good candidate, since it is involved in the formation of soluble nectin-1 tetramers (22). In addition, MAbs against the first and third domains of nectin-2 inhibited cell-cell adhesion (1). More structural data are required to definitively assess the exact configuration of the nectin-1 tetrameric complex resulting from cis- and trans-dimerization.

The region between amino acids 83 and 104 appears to be involved mainly in trans-dimerization, since both CK6 and CK8 MAbs prevented nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation. Interestingly, CK41 was not as good as CK6 or CK8 at blocking nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation, although it was a better inhibitor of HSV entry (20). It is therefore likely that the functional domain of nectin-1 involved in trans-dimerization and the gD binding domain are different, although they probably overlap in the region between amino acids 83 and 104. In addition, a point mutant of mouse nectin-2 (Phe136Leu) abolished trans-dimerization (33). This phenylalanine residue lies in a highly conserved stretch of the human nectin-1 V domain (Phe129) and might also play a role in nectin-1 trans-dimerization, either directly or indirectly, by maintaining the V domain structure.

Nectin-1-mediated aggregation occurs in a temperature-dependent manner, suggesting a dynamic process. Therefore, gD might interfere with this process in a more complex manner than just inhibiting nectin-1 trans-interaction, as documented above. It is possible that gD binding also induces or prevents changes in nectin-1 that block a dynamic step involved in aggregation, such as, for instance, the establishment of a stable interaction with afadin.

Effects of HSV on nectin-1-mediated cell aggregation.

We found that viral particles could also prevent aggregation. This effect was only partial in a previous report based on microscopic observation by Sakisaka et al. (42), probably because it requires a high particle concentration. In addition, we found that purified HSV particles were not able to dissociate preformed clumps, indicating that they did not displace enough nectin-1 to completely disrupt contacts. This might be due to a low affinity of HSV gD for nectin-1 or to an insufficient amount of available virion gD despite a multiplicity of 50 PFU/cell. Alternatively, the virus might be unable to reach enough nectin-1 within the cell junction due to steric hindrance. However, during spread of infection, the targeting of outcoming HSV directly to cell junctions would overcome these problems (28). In any case, it is unlikely that HSV needs to completely disrupt cell junctions during infection or spread, since a limited number of locally restricted nectin-1-gD interactions should be sufficient to allow entry.

In order to mimic the real interaction between the cell surface and HSV, we chose to perform inhibition experiments using unaltered virus. Under these conditions, the effects of virion gD binding and the effects of entry are not dissociated during the infection, which proceeds simultaneously with cell aggregation. However, it appears that aggregation did not occur, not even transiently, during the 90 min when cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of virus. This suggests that HSV binding to nectin-1 is critical to prevent aggregation. Indeed, we observed a rapid disappearance of the CK41 epitope on nectin-1, reflecting the binding of virion gD to the receptor. This binding also induced a change in nectin-1 accessibility to the CK35 MAb, whose epitope is located outside the V domain. This supports the idea that other domains of nectin-1 might play an active role during entry (12).

Although soluble gD did not disrupt nectin-1 cis-dimers (42), it is possible that additional envelope components act together with gD, or after gD binding, to modify or disrupt nectin-1 cis-dimers. Such a conformational change might also account for the loss of adhesive capacity of nectin-1. Thus, HSV use of nectin-1 as a receptor prevents the receptor from performing its cellular function normally. This might affect afadin binding and trigger local reorganization of actin filaments, which might benefit the virus in postentry stages.

Effects of HSV on cell surface nectin-1 early in infection.

Attachment of virus to the cell surface is mediated primarily by gC and gB bound to heparan sulfate proteoglycans (18, 27, 56). Such interaction is sensitive to heparin washes. A heparin-resistant interaction is then detected, which involves gD and its receptors (nectin-1 or HveA) (27; A. V. Nicola and S. E. Straus, Abstr. 25th Int. Herpesvirus Workshop, abstr. 2.40, 2000). The CK41 epitope on nectin-1 was not accessible when gD was bound in vitro (20). However, despite a high level of gD detected on cells incubated at 0°C with HSV, the CK41 epitope remained mostly accessible, as seen by FACS. This suggests that nectin-1 and virion gD were not fully engaged at 0°C, either because they still did not interact directly or more probably because a stabilizing step of the interaction could not take place at this temperature. Such an event might require a conformational change involving gD and/or nectin-1 and possibly other glycoproteins or cell surface components, which might only proceed at 37°C and lead to entry. Indeed, a rapid change in nectin-1 was observed during incubation at 37°C in the presence of HSV. This change was reflected by (i) disappearance of the CK41 epitope, probably due to virion gD binding, and (ii) increased accessibility of the CK35 epitope (or stability of the CK35 MAb-nectin-1 interaction). Both events occurred gradually at 37°C, while the amount of cell-bound gD remained constant. The changes in anti-nectin-1 antibody binding might be due to changes in nectin-1 structure or oligomerization or to an associated molecule in its vicinity. Perhaps these changes reflect the early assembly of a fusion complex involving multiple components from the HSV envelope and cell plasma membrane.

A conformational change in the N terminus of gD when bound to HveA compared to free gD has been described (3). Assuming that HveA and nectin-1 work in a similar fashion during entry despite their structural differences, such a change might also be observed when gD binds to nectin-1. Indeed, there was an increase in gD detection on nectin-1-expressing cells exposed to HSV which occurred within 5 min at 37°C. This increase was not observed when Control-16 cells were exposed to virus under the same conditions. This observation might reflect conformational changes in gD at an early stage of HSV entry. Alternatively, the large increase in gD staining could result from a better access to gD epitopes due directly to receptor binding or to reorganization of the glycoproteins released in the cell membrane during fusion of the viral envelope. This latter possibility could account for the gradual change of nectin-1 conformation between 5 and 30 min while the amount of gD remained constant on the cell surface. Subsequently, incoming gD released on the plasma membrane might occupy surface receptors and prevent superinfection in an interference-like mechanism (13, 19).

Structural changes induced by gD binding to nectin-1 represent one aspect of the conformational changes taking place during the dynamic evolution of the interaction between the viral envelope and the cell plasma membrane during HSV entry. The process leading to membrane fusion and the fusion mechanism itself remain unknown at the molecular level. Therefore, a closer comparison between the kinetics of the structural changes described in the present study and the kinetics of penetration will be undertaken to understand the functional significance of these structural observations in HSV entry events.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by Public Health Service grants NS-30606 and NS-36731 from the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R.J.E. and G.H.C.) and grant AI-18289 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R.J.E. and G.H.C.).

We thank Nigel Fraser, Department of Microbiology, University of Pennsylvania Medical School, for the gift of B78H1 cells. We are also grateful to Lola Kwan and Pat Spear for the C10 and Control-16 cell lines and to Fred Baribaud for his help with FACS. We acknowledge the bioengineering confocal and multiphoton core facility of the University of Pennsylvania. We also thank Pat Spear for advice and critical reading of the manuscript and the members of the Cohen and Eisenberg laboratory for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki, J., S. Koike, H. Asou, I. Ise, H. Suwa, T. Tanaka, M. Miyasaka, and A. Nomoto. 1997. Mouse homolog of poliovirus receptor-related gene 2 product, mPRR2, mediates homophilic cell aggregation. Exp. Cell Res. 235:374-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campadelli-Fiume, G., F. Cocchi, L. Menotti, and M. Lopez. 2000. The novel receptors that mediate the entry of herpes simplex viruses and animal alphaherpesviruses into cells. Rev. Med. Virol. 10:305-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carfi, A., S. H. Willis, J. C. Whitbeck, C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and D. C. Wiley. 2001. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D bound to the human receptor HveA. Mol. Cell 8:169-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiang, H.-Y., G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1994. Identification of functional regions of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein gD by using linker-insertion mutagenesis. J. Virol. 68:2529-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cocchi, F., M. Lopez, P. Dubreuil, G. Campadelli-Fiume, and L. Menotti. 2001. Chimeric nectin-1-poliovirus receptor molecules identify a nectin-1 region functional in herpes simplex virus entry. J. Virol. 75:7987-7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cocchi, F., M. Lopez, L. Menotti, M. Aoubala, P. Dubreuil, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 1998. The V domain of herpesvirus Ig-like receptor (HIgR) contains a major functional region in herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells and interacts physically with the viral glycoprotein D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15700-15705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocchi, F., L. Menotti, P. Mirandola, M. Lopez, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 1998. The ectodomain of a novel member of the immunoglobulin subfamily related to the poliovirus receptor has the attribute of a bona fide receptor for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human cells. J. Virol. 72:9992-10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, G. H., V. J. Isola, J. Kuhns, P. W. Berman, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1986. Localization of discontinuous epitopes of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D: use of a nondenaturing (“native” gel) system of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis coupled with Western blotting. J. Virol. 60:157-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connolly, S. A., J. C. Whitbeck, A. H. Rux, C. Krummenacher, S. van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2001. Glycoprotein D homologues in herpes simplex virus type 1, pseudorabies virus, and bovine herpes virus type 1 bind directly to human HveC (nectin-1) with different affinities. Virology 280:7-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean, H. J., S. S. Terhune, M. Shieh, N. Susmarski, and P. G. Spear. 1994. Single amino acid substitutions in gD of herpes simplex virus 1 confer resistance to gD-mediated interference and cause cell type-dependent alterations in infectivity. Virology 199:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eberlé, F., P. Dubreuil, M.-G. Mattei, E. Devilard, and M. Lopez. 1995. The human PRR2 gene, related to the poliovirus receptor gene (PVR), is the true homolog of the murine MPH gene. Gene 159:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geraghty, R. J., A. Fridberg, C. Krummenacher, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, and P. G. Spear. 2001. Use of chimeric nectin-1(HveC)-related receptors to demonstrate that ability to bind alphaherpesvirus gD is not necessarily sufficient for viral entry. Virology 285:366-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geraghty, R. J., C. R. Jogger, and P. G. Spear. 2000. Cellular expression of alphaherpesvirus gD interferes with entry of homologous and heterologous alphaherpesviruses by blocking access to a shared gD receptor. Virology 268:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geraghty, R. J., C. Krummenacher, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and P. G. Spear. 1998. Entry of alphaherpesviruses mediated by poliovirus receptor related protein 1 and poliovirus receptor. Science 280:1618-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graf, L. H., Jr., P. Kaplan, and S. Silagi. 1984. Efficient DNA-mediated transfer of selectable genes and unselected sequences into differentiated and undifferentiated mouse melanoma clones. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 10:139-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handler, C. G., R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 1996. Oligomeric structure of glycoproteins in herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:6067-6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herold, B. C., R. J. Visalli, N. Susmarski, C. Brandt, and P. G. Spear. 1994. Glycoprotein C-independent binding of herpes simplex virus to cells requires cell surface heparan sulfate and glycoprotein B. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1211-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herold, B. C., D. WuDunn, N. Soltys, and P. G. Spear. 1991. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 plays a principal role in the adsorption of virus to cells and in infectivity. J. Virol. 65:1090-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, R. M., and P. G. Spear. 1989. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D mediates interference with herpes simplex virus infection. J. Virol. 63:819-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krummenacher, C., I. Baribaud, M. Ponce de Leon, J. C. Whitbeck, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 2000. Localization of a binding site for herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D on the herpesvirus entry mediator C by using anti-receptor monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 74:10863-10872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krummenacher, C., A. V. Nicola, J. C. Whitbeck, H. Lou, W. Hou, J. D. Lambris, R. J. Geraghty, P. G. Spear, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1998. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D can bind to poliovirus receptor-related protein 1 or herpesvirus entry mediator, two structurally unrelated mediators of virus entry. J. Virol. 72:7064-7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krummenacher, C., A. H. Rux, J. C. Whitbeck, M. Ponce de Leon, H. Lou, I. Baribaud, W. Hou, C. Zou, R. J. Geraghty, P. G. Spear, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 1999. The first immunoglobulin-like domain of HveC is sufficient to bind herpes simplex virus gD with full affinity while the third domain is involved in oligomerization of HveC. J. Virol. 73:8127-8137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuriyama, M., N. Harada, S. Kuroda, T. Yamamoto, M. Nakafuku, A. Iwamatsu, D. Yamamoto, R. Prasad, C. Croce, E. Canaani, and K. Kaibuchi. 1996. Identification of AF-6 and canoe as putative targets for Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 271:607-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauri, D., C. De Giovanni, T. Biondelli, E. Lalli, L. Landuzzi, A. Facchini, G. Nicoletti, P. Nanni, E. Dejana, and P. L. Lollini. 1993. Decreased adhesion to endothelial cells and matrix proteins of H-2Kb gene transfected tumour cells. Br. J. Cancer 68:862-867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez, M., F. Cocchi, L. Menotti, E. Avitabile, P. Dubreuil, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2000. Nectin2alpha (PRR2α or HveB) and nectin2delta are low-efficiency mediators for entry of herpes simplex virus mutants carrying the Leu25Pro substitution in glycoprotein D. J. Virol. 74:1267-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez, M., F. Eberlé, M.-G. Mattei, J. Gabert, F. Birg, F. Bardin, C. Maroc, and P. Dubreuil. 1995. Complementary DNA characterization and chromosomal localization of a human gene related to the poliovirus receptor-encoding gene. Gene 155:261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClain, D. S., and A. O. Fuller. 1994. Cell-specific kinetics and efficiency of herpes simplex virus type 1 entry are determined by two distinct phases of attachment. Virology 198:690-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMillan, T. N., and D. C. Johnson. 2001. Cytoplasmic domain of herpes simplex virus gE causes accumulation in the trans-Golgi network, a site of virus envelopment and sorting of virions to cell junctions. J. Virol. 75:1928-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendelsohn, C. L., E. Wimmer, and V. R. Racaniello. 1989. Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell 56:855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menotti, L., M. Lopez, E. Avitabile, A. Stefan, F. Cocchi, J. Adelaide, E. Lecocq, P. Dubreuil, and G. Campadelli-Fiume. 2000. The murine homolog of human nectin 1 delta serves as a species nonspecific mediator for entry of human and animal alphaherpesviruses in a pathway independent of detectable binding to gD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4867-4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, C. G., C. Krummenacher, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and N. W. Fraser. 2001. Development of a syngenic murine B16 cell line-derived melanoma susceptible to destruction by neuroattenuated HSV-1. Mol. Ther. 3:160-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milne, R. S. B., S. A. Connolly, C. Krummenacher, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2001. Porcine HveC, a member of the highly conserved HveC/nectin 1 family, is a functional alphaherpesvirus receptor. Virology 281:315-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyahara, M., H. Nakanishi, K. Takahashi, K. Satoh-Horikawa, K. Tachibana, and Y. Takai. 2000. Interaction of nectin with afadin is necessary for its clustering at cell-cell contact sites but not for its cis dimerization or trans interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 275:613-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery, R. I., M. S. Warner, B. J. Lum, and P. G. Spear. 1996. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell 87:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison, M. E., and V. R. Racaniello. 1992. Molecular cloning and expression of a murine homolog of the human poliovirus receptor gene. J. Virol. 66:2807-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muggeridge, M. I. 2000. Characterization of cell-cell fusion mediated by herpes simplex virus 2 glycoproteins gB, gD, gH and gL in transfected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2017-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicola, A. V., C. Peng, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1997. Antigenic structure of soluble herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D correlates with inhibition of HSV infection. J. Virol. 71:2940-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicola, A. V., M. Ponce de Leon, R. Xu, W. Hou, J. C. Whitbeck, C. Krummenacher, R. I. Montgomery, P. G. Spear, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 1998. Monoclonal antibodies to distinct sites on the herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D block HSV binding to HVEM. J. Virol. 72:3595-3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishioka, H., A. Mizoguchi, H. Nakanishi, K. Mandai, K. Takahashi, K. Kimura, A. Satoh-Moriya, and Y. Takai. 2000. Localization of l-afadin at puncta adhaerentia-like junctions between the mossy fiber terminals and the dendritic trunks of pyramidal cells in the adult mouse hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 424:297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reymond, N., J. Borg, E. Lecocq, J. Adelaide, G. Campadelli-Fiume, P. Dubreuil, and M. Lopez. 2000. Human nectin3/PRR3: a novel member of the PVR/PRR/nectin family that interacts with afadin. Gene 255:347-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rux, A. H., S. H. Willis, A. V. Nicola, W. Hou, C. Peng, H. Lou, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1998. Functional region IV of glycoprotein D from herpes simplex virus modulates glycoprotein binding to the herpes virus entry mediator. J. Virol. 72:7091-7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakisaka, T., T. Taniguchi, H. Nakanishi, K. Takahashi, M. Miyahara, W. Ikeda, S. Yokoyama, Y. F. Peng, K. Yamanishi, and Y. Takai. 2001. Requirement of interaction of nectin-1α/HveC with afadin for efficient cell-cell spread of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 75:4734-4743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satoh-Horikawa, K., H. Nakanishi, K. Takahashi, M. Miyahara, M. Nishimura, K. Tachibana, A. Mizoguchi, and Y. Takai. 2000. Nectin-3, a new member of immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecules that shows homophilic and heterophilic cell-cell adhesion activities. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10291-10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shukla, D., M. C. DalCanto, C. L. Rowe, and P. G. Spear. 2000. Striking similarity of murine nectin-1α to human nectin-1α (HveC) in sequence and activity as a gD receptor for alphaherpesvirus entry. J. Virol. 74:11773-11781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shukla, D., J. Liu, P. Blaiklock, N. W. Shworak, X. Bai, J. D. Esko, G. H. Cohen, R. J. Eisenberg, R. D. Rosenberg, and P. G. Spear. 1999. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell 99:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sisk, W. P., J. D. Bradley, R. J. Leipold, A. M. Stoltzfus, M. Ponce de Leon, M. Hilf, C. Peng, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1994. High-level expression and purification of secreted forms of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gD synthesized by baculovirus-infected insect cells. J. Virol. 68:766-775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sodeik, B., M. W. Ebersold, and A. Helenius. 1997. Microtubule-mediated transport of incoming herpes simplex virus 1 capsids to the nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 136:1007-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spear, P. G., R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2000. Three classes of cell surface receptors for alphaherpesvirus entry. Virology 275:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi, K., H. Nakanishi, M. Miyahara, K. Mandai, K. Satoh, A. Satoh, H. Nishioka, J. Aoki, A. Nomoto, A. Mizoguchi, and Y. Takai. 1999. Nectin/PRR: an immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule recruited to cadherin-based adherens junctions through interaction with afadin, a PDZ domain-containing protein. J. Cell Biol. 145:539-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turner, A., B. Bruun, T. Minson, and H. Browne. 1998. Glycoproteins gB, gD, and gHgL of herpes simplex virus type 1 are necessary and sufficient to mediate membrane fusion in a Cos cell transfection system. J. Virol. 72:873-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warner, M. S., W. Martinez, R. J. Geraghty, R. I. Montgomery, J. C. Whitbeck, R. Xu, R. J. Eisenberg, G. H. Cohen, and P. G. Spear. 1998. A cell surface protein with herpesvirus entry activity (HveB) confers susceptibility to infection by herpes simplex virus type 2, mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 and pseudorabies virus. Virology 246:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitbeck, J. C., S. A. Connolly, S. H. Willis, W. Hou, C. Krummenacher, M. Ponce de Leon, H. Lou, I. Baribaud, R. J. Eisenberg, and G. H. Cohen. 2001. Localization of the gD-binding region of the human herpes simplex virus receptor, HveA. J. Virol. 75:171-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitbeck, J. C., C. Peng, H. Lou, R. Xu, S. H. Willis, M. Ponce de Leon, T. Peng, A. V. Nicola, R. I. Montgomery, M. S. Warner, A. M. Soulika, L. A. Spruce, W. T. Moore, J. D. Lambris, P. G. Spear, G. H. Cohen, and R. J. Eisenberg. 1997. Glycoprotein D of herpes simplex virus (HSV) binds directly to HVEM, a member of the TNFR superfamily and a mediator of HSV entry. J. Virol. 71:6083-6093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wisner, T., C. Brunetti, K. Dingwell, and D. C. Johnson. 2000. The extracellular domain of herpes simplex virus gE is sufficient for accumulation at cell junctions but not for cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 74:2278-2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wittels, M., and P. G. Spear. 1990. Penetration of cells by herpes simplex virus does not require a low pH-dependent endocytic pathway. Virus Res. 18:271-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.WuDunn, D., and P. G. Spear. 1989. Initial interaction of herpes simplex virus with cells is binding to heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 63:52-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]