Abstract

We previously showed that intradermal immunization with plasmids expressing the murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) protein IE1-pp89 or M84 protects against viral challenge and that coimmunization has a synergistic protective effect (C. S. Morello, L. D. Cranmer, and D. H. Spector, J. Virol. 74:3696-3708, 2000). Using an intracellular gamma interferon cytokine staining assay, we have now characterized the CD8+ T-cell response after DNA immunization with pp89, M84, or pp89 plus M84. The pp89- and M84-specific CD8+ T-cell responses peaked rapidly after three immunizations. DNA immunization and MCMV infection generated similar levels of pp89-specific CD8+ T cells. In contrast, a significantly higher level of M84-specific CD8+ T cells was elicited by DNA immunization than by MCMV infection. Fusion of ubiquitin to pp89 enhanced the CD8+ T-cell response only under conditions where vaccination was suboptimal. Three immunizations with either pp89, M84, or pp89 plus M84 DNA also provided significant protection against MCMV infection for at least 6 months, with the best protection produced by coimmunization. A substantial percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells remained detectable, and they responded rapidly to the MCMV challenge. These results underscore the importance of considering antigens that do not appear to be highly immunogenic during infection as DNA vaccine candidates.

The cytomegaloviruses (CMVs) are large, species-specific, double-stranded DNA viruses that can establish persistent and latent infections in their hosts. Although infection in immunocompetent individuals is usually benign, human CMV (HCMV) is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in immunosuppressed individuals. It is also the major viral cause of birth defects. Each year 0.5 to 2.5% of newborns are congenitally infected with CMV, and 5 to 10% of these infected infants will display neurologic defects such as hearing loss and impaired learning abilities (2).

Although extensive biological and immunological studies have been performed with HCMV, progress has been greatly impeded by the species-specific nature of the virus. Consequently, no animal models are available for direct study of the pathogenesis of HCMV and testing of preventive strategies. Murine CMV (MCMV) greatly resembles its human counterpart with respect to acute infection, establishment of latency, and reactivation after immunosuppression. Because HCMV and MCMV also have much in common with respect to the organization and expression of their genomes and host immune response to the viral gene products, this animal model system has been very useful for the development and testing of strategies for prevention and treatment of CMV infection.

MCMV encodes several proteins that play significant roles in the control of virus replication through the induction of adaptive immune responses in its host. Some of the gene products have homologs in HCMV, while others are unique to MCMV. Both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are induced during MCMV infection. Two of the HCMV and MCMV glycoproteins, gB and gH, are major participants in eliciting humoral immune responses (3, 22, 27, 28). Although the response is vigorous, several studies have documented that the neutralization antibodies induced by HCMV are not sufficient to control the virus infection (7, 36).

In contrast, cell-mediated immune responses play a central role in controlling CMV infection. Depletion of either CD8+ or CD4+ T cells has severe consequences in MCMV-infected mice (18, 20), and adoptive transfer of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) from MCMV-infected mice to recipients significantly inhibits virus replication (35). To date, four gene products, pp89, M83, M84, and m04, have been reported to elicit cell-mediated immune responses during MCMV infection.

The MCMV immediate-early (IE) protein pp89, which is the counterpart of the HCMV 72-kDa IE1 protein, was the first gene product identified that generated a strong CTL response (29). The major CTL epitope of pp89 corresponds to the nonapeptide 168YPHFMPTNL176 (30). It is a dominant CTL epitope in infected BALB/c mice (15) and plays a significant role in controlling the replication of the virus (26). In early studies, it was shown that immunization of mice with recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing either full-length pp89 or the CTL epitope fragment was able to induce strong protective immune responses against subsequent lethal MCMV challenge (6, 19). Subsequently, we demonstrated that when BALB/c mice were immunized with a plasmid expressing MCMV pp89, strong CTL responses were induced that were able to protect the mice from lethal MCMV challenge and inhibit viral replication after sublethal challenge (10, 24).

The m04 gene encodes a glycoprotein (gp34) that is unique to MCMV and is expressed during the early phase of infection (16). The major epitope within the protein has been mapped to the sequence 243YGPSLYRRF251, and a CTL line directed against this epitope has been shown to be protective when it is adoptively transferred to immunodeficient recipients. Interestingly, this protein can form a complex with major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules that can escape the MCMV-mediated retention of MHC class I complexes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This observation has led to the hypothesis that m04 might be an NK cell decoy gene (16, 21).

The MCMV M83 and M84 genes are both homologs of the HCMV UL83 gene (4). The M83 protein is expressed with early-late gene kinetics and is present in the virion, while the M84 gene product is a nonstructural protein that is expressed at early times in infection (4, 23). Of particular interest was our finding that the M84 open reading frame (ORF) of MCMV has greater homology to the HCMV UL83 ORF than does the positional homolog M83 (4). The product of the HCMV UL83 gene is pp65, a matrix protein that is a major target of the protective CTL response in humans. Both M83 and M84 have also been found to be immunogenic, and CTL epitopes for both proteins have recently been identified. The epitope in the 105-kDa M83 protein is Ld restricted and corresponds to the sequence 761YPSKEPFNF769 (14), while the epitope in the 65-kDa M84 protein is Kd restricted and has been mapped to the sequence 297AYAGLFTPL305 (17). Although the CTL response directed against the M84 epitope is very weak and at the limit of detection following infection, a CTL cell line against the M84 epitope, as well as one against the M83 epitope, has been generated, and both cell lines have been shown to confer protection against MCMV in an adoptive transfer experiment (14). However, the M83-specific T-cell line appeared to be more protective than the M84-specific T-cell line. This result is in contrast to our previous study showing that immunization of mice with DNA encoding M84, but not M83, provided strong protection against viral replication in the spleen when mice were challenged with MCMV (24). Immunization of mice with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing M83 also provided no protection. Whether the absence of protection was due to the inability of the M83 vaccine to prime the CTLs or the lack of expansion of the primed CTLs upon MCMV challenge remains to be determined.

For many years, we have utilized MCMV infections in mice as a model for uniting studies on the molecular biology and in vivo pathogenesis of the virus. The goal of our most recent research has been to develop a DNA-based vaccine that will protect fully against acute and latent CMV infection. Previously, we demonstrated that BALB/c mice immunized intradermally (i.d.) with plasmids expressing pp89 and M84 were protected against subsequent MCMV challenge as measured by reduction of viral titers in the spleen (10, 24). Moreover, a synergistic effect was observed when mice were coimmunized with pp89 and M84. We also demonstrated that the protection provided by vaccination of mice with the plasmid expressing pp89 correlated with a strong CTL response against the pp89 protein (10). In the case of M84, we initially reasoned that because the protein is nonstructural, the protective immunity elicited by the M84 plasmid was most likely cell mediated (23). This hypothesis was supported by our studies showing that M84-mediated protection from challenge required M84 expression by the challenge virus in the host. However, the precise immunological mechanism underlying the protection provided by M84 DNA remained to be determined. This was a particularly important question to address in view of the evidence that M84 was a relatively weak immunogen during infection. With the recent identification of a nonapeptide that is a CTL epitope in M84 (17) and the development of the highly sensitive and relatively simple intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) assay, it became possible to determine the CTL response following immunization with M84 DNA. A major advantage of this assay is that it permits direct ex vivo detection of the specific CD8+ T-cell responses without the need for extensive antigen stimulation in vitro.

In this study, we used the ICCS assay to examine the kinetics of accumulation and the percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes present in the spleen after mice were either immunized with DNA vectors expressing pp89 and M84 or infected with MCMV. We also investigated the immune responses and protection elicited when the DNA vaccines encoded pp89 or M84 fused to ubiquitin. Finally, we have determined whether DNA immunization confers long-term immunity and protection against infection. We show that DNA immunization induced a strong CD8+ T-lymphocyte response against both epitopes and that a significant percentage of these CD8+ T lymphocytes became memory cells. The percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes elicited following DNA immunization was comparable to that generated following MCMV infection. In contrast, DNA immunization resulted in a significantly higher level of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes than MCMV infection. We also found that fusion of the ubiquitin gene to the DNA coding for pp89 enhanced the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response only when DNA immunization was suboptimal. Finally, we document that immunization with DNA encoding pp89 and M84 generated a specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte response and protection against infection that persisted for at least 6 months.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Three- to 4-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan-Sprague-Dawley, Inc. Upon arrival, mice were housed in microisolator-covered cages in the biology vivarium facility at the University of California, San Diego. Mice were allowed to adjust to the facility for another 1 to 2 weeks before any experiments were performed.

Cell culture.

NIH 3T3 cells (ATCC CRL-1658) were maintained in DME-10 (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM], low glucose, supplemented with 10% [vol/vol] heat-inactivated bovine calf serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine [Gibco BRL]). COS-7 cells (ATCC CRL-1651) were cultured in DMEM, high glucose, supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco BRL).

Virus propagation.

MCMV strain K181 was grown in NIH 3T3 cells (tissue culture virus) and was isolated from the salivary glands of infected BALB/c mice (salivary gland-derived virus) as described previously (24), with minor modifications. To prepare salivary gland-derived virus, 4- to 5-week-old female BALB/c mice were infected with 3 × 104 PFU of MCMV/mouse by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Ten days later, the mice were sacrificed with CO2. The salivary glands were harvested, and four salivary glands were homogenized each time with a Dounce homogenizer in the presence of 4 ml of freezing medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide). Homogenates were pooled and centrifuged at 4°C and 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of freezing medium and homogenized further. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 × g, and the supernatant was combined with the first supernatant. The resulting virus was further centrifuged at 4,000 × g and 4°C for 25 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min in a Sorvall centrifuge. The virus preparation was frozen in aliquots at −70°C, and the titer of the virus was determined by a standard plaque assay. New virus preparations typically had a 50% lethal dose (LD50) of approximately 750,000 PFU. An older batch of salivary gland-derived MCMV prepared in 1996 was also used in some of the experiments and is indicated with an asterisk (*) in the text (10). The older virus preparation had an LD50 of 250,000 PFU.

Construction of plasmids expressing MCMV proteins fused to ubiquitin.

Plasmids used for expressing amino-terminal ubiquitin fusion proteins were constructed by using a pcDNA3-based parent vector and the ubiquitin coding sequence amplified from mouse genomic DNA by PCR. Briefly, the pc3Δneo vector was constructed by deleting a 1.1-kbp fragment between the SmaI and BsmI sites in the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). The deleted sequence contains the neomycin resistance gene cassette. The sequence coding for the ubiquitin monomer was amplified by PCR using four different primers. A sense strand oligonucleotide was synthesized such that the 5" end contained a HindIII site (underlined) and a Kozak consensus sequence: 5"-CC AAG CTT GCC ACC ATG CAG-3" (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.). Three antisense primers corresponding to three ORFs were synthesized such that each 3" end contained a BamHI site (underlined): primer a, 5"-CG GGA TCC TAA GGC ACC TCT CAG GCG AAG GAC CAG GTG-3"; primer b, 5"-CGG GAT CCC TAA GGC ACC TCT CAG GCG AAG GAC CAG GTG CAG-3"; and primer c, 5"-C GGG ATC CCC TAA GGC ACC TCT CAG GCG AAG GAC CAG GTG CAG G-3". PCRs were performed by using the sense primer and one of the antisense primers with BALB/c mouse spleen DNA (purified by Qiagen Tissue Prep) as a template and cloned Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). Following 30 cycles, the 250-bp products were digested with HindIII and BamHI and were gel purified. The resulting PCR products were then ligated to the pc3Δneo vector between the HindIII and BamHI sites. After transformation, the identities of the resulting clones, designated pc3-Ua, -Ub, and -Uc, were confirmed by restriction analysis and dideoxy sequencing (Sequenase; Amersham). To construct pc3-U-pp89, a DNA fragment coding for pp89 was subcloned into pc3-Uc at the EcoRI site. Similarly, pc3-U-M84 was constructed by subcloning the M84 ORF (4) into a pc3-Ua vector at the BamHI and EcoRI sites. The junctions between the ubiquitin and MCMV genes were sequenced to ensure that the reading frame was correct.

Expression of full-length ubiquitin fusion proteins was first determined by use of a TNT Quick Coupled In Vitro Transcription/Translation T7 kit (Promega) containing [35S]methionine. The labeled proteins were assayed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by autoradiography. Expression from the HCMV major immediate-early (MIE) promoter/enhancer was subsequently investigated by transient transfection of COS-7 or NIH 3T3 cells using DEAE-dextran transfection or electroporation, respectively. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-7.5% PAGE, followed by transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane. Expression of U-pp89 and U-M84 was confirmed by Western blotting with BALB/c anti-MCMV hyperimmune serum and affinity purified rabbit anti-glutathione S-transferase (GST)-M84 serum, respectively (23). Antibody-specific protein bands were detected by using the Pierce SuperSignal West Pico kit (catalog no. 34080) followed by fluorography as suggested by the manufacturer.

Immunization and challenge of mice with MCMV.

The backs of the mice were shaved, and the indicated amount of plasmid DNA in 30 μl of endotoxin-free normal saline was injected i.d. by using a 0.5-ml syringe with a 28 1/2-gauge needle. At varying intervals after the last immunization, several mice in each group were sacrificed, and their spleens were harvested for ICCS assay. The remainder of the mice were i.p. challenged with an indicated amount of MCMV, typically 0.3 to 0.5 LD50 in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Actual challenge doses used were dependent on the virulence of the viral preparation and the immunity status of the mouse. Five days after challenge, the mice were sacrificed, and spleen homogenates were prepared with a Dounce homogenizer in 1 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and were stored at −70°C. The infectious MCMV present in the organ homogenates was subsequently quantified by plaque assay on NIH 3T3 monolayers in 24-well dishes.

ICCS assay.

ICCS was performed as described previously (1, 12, 34), with minor modifications. Briefly, splenocytes were isolated, red blood cells were removed, and the resulting splenocytes were washed once with RP-10 (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mM l-glutamine). Splenocytes were subsequently counted and then resuspended in RP-10 at 2 × 107 cells per ml. To stimulate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, 100 μl of splenocytes was mixed with 100 μl of RP-10 containing 2 μM specific nonapeptide (168YPHFMPTNL176 for pp89 and 297AYAGLFTPL305 for M84) and a 1:500 dilution of GolgiPlug containing brefeldin A (catalog no. 2301kz; PharMingen). Background cytokine staining was determined by incubating the cells in the same medium in the absence of peptide. After incubation at 37°C for 5 h, cells were pelleted and then resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 2% FBS and 0.09% sodium azide) containing 1:100-diluted Fc Block (catalog no. 553142; PharMingen). After incubation on ice for 15 min, cells were pelleted and then resuspended in FACS buffer containing a 1:250-diluted fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD8a monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 553031; PharMingen). Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min or overnight, washed twice with FACS buffer, and then fixed and permeabilized by using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit as suggested by the manufacturer (catalog no. 554714; PharMingen). Intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) was detected by incubating the cells on ice for 30 min with a 1:100 dilution of R-phycoerythrin-conjugated rat monoclonal antibody against mouse IFN-γ (catalog no. 18115A; PharMingen). After the cells were washed with Cytoperm/Cytowash and FACS buffer, they were resuspended in FACS buffer. The stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Usually 300,000 to 500,000 cells of the small lymphocyte population were analyzed. IFN-γ antigen positive CD8+ T cells were enumerated using B.D. Flow Cytomete software (Elite) and expressed as a percentage of total CD8+ T cells.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher's protected least significant difference post-hoc test.

RESULTS

Strong CD8+ T-cell responses are induced by vaccination of BALB/c mice with plasmids expressing pp89 or M84.

When we first began the DNA immunization experiments, we confirmed that CTLs were generated in response to pp89 by using the traditional CTL lysis assay (10). This was a labor-intensive procedure that required a lengthy period of antigen restimulation and did not provide a measurement of the actual percentage of antigen-specific CTLs generated. The recent development of a rapid assay that involves ICCS to measure CD8+ T-cell responses made these analyses far easier to perform (1, 34). This method is based on the observation that following antigen stimulation, both effector and memory CTLs synthesize and secrete IFN-γ. This synthesis stops as soon as antigen engagement is disrupted. By blocking the protein secretory pathway, the newly synthesized IFN-γ accumulates inside the CD8+ T cells, and the antigen-dependent, IFN-γ-positive CD8+ T cells can be detected and enumerated by FACS.

To measure the percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen after mice were immunized with a plasmid(s) expressing pp89, M84, or pp89 plus M84, we performed the ICCS assay by using the epitope peptides that had been identified for pp89 and M84 for antigen stimulation (17, 30). The optimal concentrations of the pp89 and M84 peptides in the assay were first determined by using splenocytes isolated from mice 1 month after infection with 2.5 × 105 PFU of salivary gland-derived MCMV. The results showed that mouse splenocytes responded equally well to the pp89 peptide over a range of 10 nM to 10 μM and to the M84 peptide over a range of 1 nM to 1 μM (data not shown). Therefore, a final concentration of 1 μM pp89 or M84 peptide was used in the ICCS assays to stimulate splenocytes from vaccinated mice.

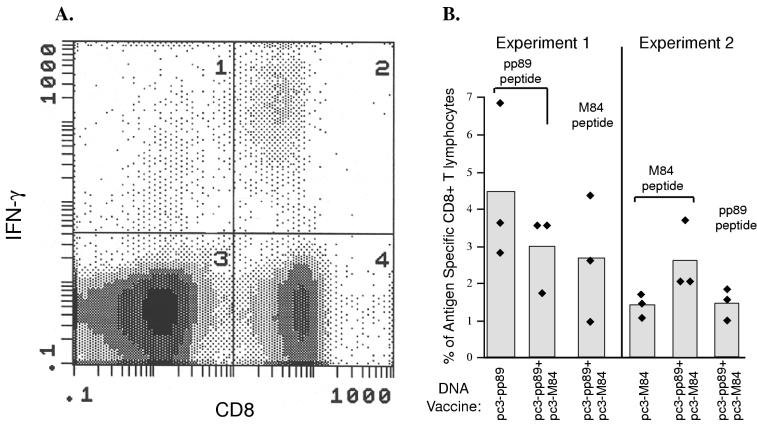

Figure 1 presents the results of two separate experiments in which we used the ICCS assay to measure the levels of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the splenocytes of mice 7 days after three immunizations of pc3-pp89 or pc3-pp89 plus pc3-M84 (experiment 1) or 7 days after three immunizations of pc3-M84 or pc3-pp89 plus pc3-M84 (experiment 2). A representative FACS analysis of splenocytes from mice immunized with pc3-pp89 is shown in Fig. 1A. The presence of a significant population of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing IFN-γ (quadrant 2) indicates that DNA immunization induced a strong CD8+ T-lymphocyte response against the pp89 epitope. In experiment 1, we found that in mice immunized three times over 20 days with 10 μg of pc3-pp89 DNA alone, approximately 4.5% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes were directed against the pp89 epitope (Fig. 1B). Similarly, three immunizations of mice with 10 μg each of pc3-pp89 and pc3-M84 resulted in an average of 2.7% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes being specific for the pp89 or M84 epitope. In experiment 2, approximately 1.4% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes were specific for the M84 epitope following three immunizations with 10 μg of pc3-M84 DNA alone. Following coimmunization with pc3-pp89 and pc3-M84, approximately 1.5% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes were directed against pp89 while the percentage of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes was slightly higher (2.7%). These results showed that a significant percentage of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes were specific for pp89 and M84 following immunization with pc3-pp89 and pc3-M84, either alone or in combination.

FIG. 1.

BALB/c mice were immunized three times with 10 μg of vector alone (pc3Δneo), pc3-pp89, or pc3-pp89 plus pc3-M84 (B, experiment 1) or with 10 μg of pc3Δneo, pc3-M84, or pc3-pp89 plus pc3-M84 (B, experiment 2),over a 20-day period. Ten days after the last immunization, splenocytes were prepared from the immunized mice. pp89 or M84 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes were measured by ICCS as described in Materials and Methods. The level of pp89 or M84 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes was calculated as a percentage of total spleen CD8+ T cells. (A) Representative density dot plot showing a flow cytometry analysis of IFN-γ positive CD8+ T lymphocytes from pc3-pp89 DNA-immunized mice stimulated with pp89 peptide. The CD8 and IFN-γ double-positive cells are located in quadrant 2. (B) Levels of pp89 or M84 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the spleens of immunized mice. The average background level measured in pc3Δneo-immunized mice was subtracted from the level obtained for the immunized mice in experiment 1. The value obtained in the absence of peptide stimulation for splenocytes from the immunized mice in experiment 2 was similar to that obtained from vector-immunized mice and was subtracted from the value measured in the presence of peptide stimulation. The peptides used to stimulate the lymphocytes are shown above the bars.

Kinetics of the CTL response after DNA immunization.

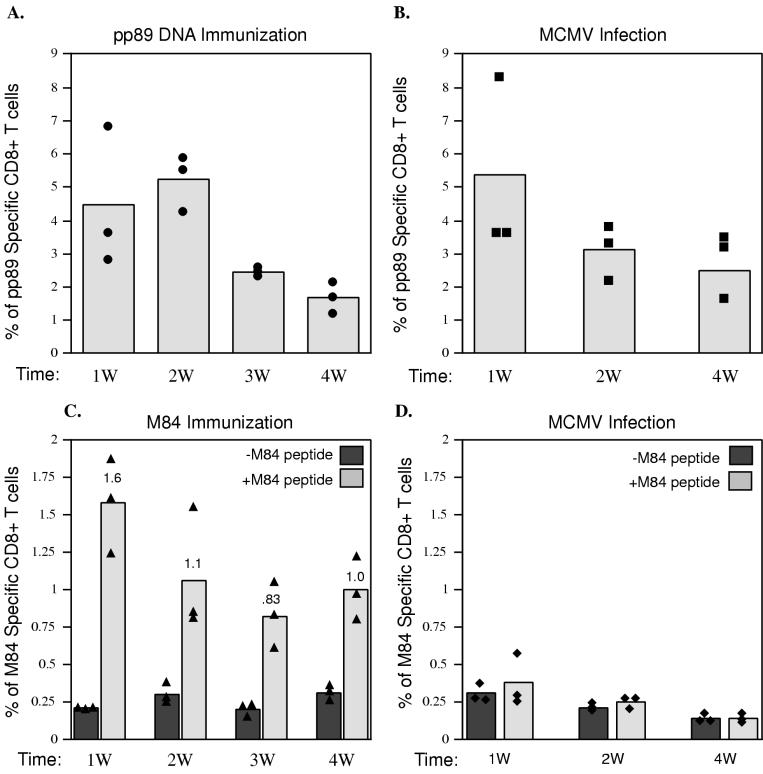

Since the ICCS assay is very sensitive and quantitative, it can be used to investigate the kinetics of the CTL response after DNA-based immunization. Previously, we found that following three i.d. injections of the DNA vaccine, mice were protected from subsequent MCMV challenge at 10 or 14 days after the last immunization. We were therefore interested in whether the kinetics of the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response following immunization was correlated with the protection observed. To this end, CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were monitored over a 4-week period for the group of mice that were i.d. injected three times with 10 μg of pc3-pp89 or pc3-M84 DNA as described for experiments 1 and 2 of Fig. 1. As can be seen in Fig. 2A, a strong CD8+ T-lymphocyte response against the pp89 peptide was detected at the end of the 1st week after the final immunization and remained at a high level until week 3. At this time, the percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes decreased approximately twofold.

FIG. 2.

BALB/c mice were either immunized with DNA as described for experiments 1 and 2 of Fig. 1 (A and C, respectively) or infected with 1.2 × 105 PFU of tissue culture-derived MCMV (B and D). At 1, 2, 3, or 4 weeks (W) after the last immunization or infection, mouse splenocytes were prepared for ICCS as described in Materials and Methods. pp89 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes from pc3-pp89-immunized mice (A) and MCMV-infected mice (B) or M84 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes from pc3-M84-immunized mice (C) and MCMV-infected mice (D) were measured and expressed as percentages of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes. Bars represent average values for three mice; solid symbols represent values for individual mice. For the data shown in panel A, the background level of pp89-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleens of pc3Δneo (vector alone)-immunized mice was subtracted from the levels measured for pc3-pp89-immunized mice. For the data in panel B, the background number in the absence of pp89 peptide was subtracted from the values measured for MCMV-infected mice. In panels C and D, values measured in the presence (+M84 peptide) and in the absence (−M84 peptide) of M84 peptide stimulation in pc3-M84-immunized or MCMV-infected mice are shown.

Figure 2C shows the kinetics of the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response against the M84 epitope. The peak response of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the M84 epitope (1.4% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes) was detected at the end of week 1. At week 2, the percentage of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes showed a modest decline (approximately 1.5-fold) and then remained at this level through week 4.

These results indicate that a strong CD8+ T-lymphocyte response against both epitopes was induced rapidly and that a significant percentage of these CD8+ T lymphocytes became memory cells. As will be shown below, the frequencies of the pp89- and M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes remained at these high levels for at least 6 months after immunization.

Comparison of M84- and pp89-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses in mice immunized with DNA versus mice infected with MCMV.

In previous studies, we showed that immunization of BALB/c mice with a pp89-expressing plasmid generated levels of pp89 nonapeptide-specific CTL activity similar to those generated by immunization with tissue culture-derived MCMV (10). Recently, Holtappels et al. (17) reported that although the M84 peptide described above could support the generation of a specific CTL line from mouse splenocytes that were isolated 3 months after MCMV infection, the frequency of the M84 peptide-specific memory CD8+ T lymphocytes was too low to be detected in an IFN-γ-based ex vivo ELISpot assay. Yet pp89 peptide-specific memory CD8+ T lymphocytes were readily detectable in the ELISpot assay. This was surprising given the results of our previous work and the studies reported here showing that immunization with M84 DNA elicited a protective response and M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes that could easily be detected by the ICCS assay. We were therefore interested in using the ICCS assay to determine the levels of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in mice infected with various amounts of tissue culture-derived MCMV and to compare these with the results following DNA immunization. At the same time, the ICCS assay could be used to measure the frequency of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated following infection versus DNA immunization.

To determine whether the observed kinetics of induction of pp89- and M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes following DNA immunization were similar to those following infection, we infected mice i.p. with 1.2 × 105 PFU of tissue culture-derived MCMV and isolated the spleen cells at various times during the next 4 weeks. Figure 2B shows that the pp89-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte response peaked at the end of the 1st week and then dropped approximately twofold during the 2nd week. This population of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes then remained stable during the following 2 weeks. At the peak, the percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated by DNA immunization was comparable to that following infection and comprised approximately 5% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 2A).

The results with respect to M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes were strikingly different (Fig. 2C and D). Figures 2C and D show the uncorrected data obtained when splenocytes were incubated in the presence and absence of the M84 peptide. In agreement with the data of Holtappels et al. (17), the level of CD8+ T lymphocytes directed against M84 in mice infected with MCMV remained at background during the entire 4-week period (0.1 to 0.2% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes) (Fig. 2D). In contrast, in DNA-immunized mice, approximately 1.4% (corrected) of CD8+ T lymphocytes were specific for M84 at the end of week 1, and at the end of week 4, approximately 0.7% (corrected) of the CD8+ T lymphocytes were still M84 specific (Fig. 2C). Therefore, these results demonstrate that antigens that do not appear to be highly immunogenic during infection can be good vaccine candidates (8, 32).

CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses after immunization with DNA expressing pp89 and M84 fused at the amino terminus with ubiquitin.

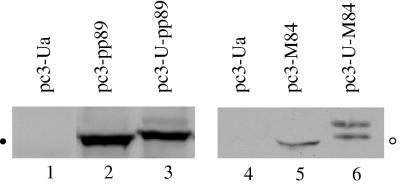

Several studies have shown that immunization with DNA encoding antigen-ubiquitin fusion proteins increased both antigen presentation and CTL responses to that immunogen (31, 33). We therefore were interested in determining whether fusion of the ubiquitin sequence to the ends of the pp89 and M84 genes corresponding to the amino termini could enhance the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response and protection from MCMV challenge. Because the ubiquitin moiety in the fusion protein tends to be removed before the formation of the polyubiquitin complex (33), we changed the codon for glycine at position 76 to alanine in order to stabilize the fusion protein. To confirm that the fusion proteins could be expressed from the recombinant plasmids pc3-U-pp89 and pc3-U-M84, we first assayed the products generated when the DNA constructs were placed in an in vitro transcription-translation reaction. The resulting proteins migrated more slowly on gels than did pp89 and M84, indicating that the fusion proteins were being generated (data not shown). These recombinant plasmids were subsequently transfected into COS-7 cells (pc3-pp89 and pc3-U-pp89) or NIH 3T3 cells (pc3-M84 and pc3-U-M84). Two days after transfection, the cells were lysed and the steady-state levels of pp89 and M84 proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-MCMV hyperimmune serum and a rabbit anti-GST-M84 serum, respectively. Figure 3 shows that the major form corresponding to the ubiquitinated pp89 from cells transfected with pc3-U-pp89 (lane 3) migrated more slowly than the pp89 protein from cells transfected with pc3-pp89 (lane 2). A minor band detected above the major band in lane 3 may represent one form of polyubiquitinated pp89. Similarly, the M84 species detected in cells transfected with pc3-U-M84 (lane 6) migrated more slowly than that from cells transfected with pc3-M84 (lane 5). The upper band in lane 6 may also represent a form of polyubiquitinated M84. The similar intensities of protein bands representing ubiquitinated and nonubiquitinated forms of pp89 and M84 indicate that the steady-state levels of the two forms of pp89 and M84 are comparable in the transient transfection assay.

FIG. 3.

COS-7 cells (lanes 1 to 3) or NIH 3T3 cells (lanes 4 to 6) were transfected with vector pc3-Ua (lanes 1 and 4), pc3-pp89 (lane 2), pc3-U-pp89 (lane 3), pc3-M84 (lane 5), or pc3-U-M84 (lane 6). Two days after transfection, cells were lysed in loading buffer, sonicated, and heated to 100°C (pp89 and U-pp89) or 42°C (M84 and U-M84). The resulting proteins were separated by SDS-7.5% PAGE. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, pp89 and U-pp89 were detected by using a mouse anti-MCMV hyperserum (lanes 1 to 3), and M84 and U-M84 were detected by using a rabbit anti-GST-M84 serum (lanes 4 to 6). MCMV-specific protein bands were detected with a Pierce SuperSignal West Pico kit. The solid circle in the left margin stands for the location of a protein band corresponding to pp89 and has a molecular mass of approximately 89 kDa. The open circle in the right margin stands for the location of a protein band corresponding to M84 and has a molecular mass of approximately 65 kDa.

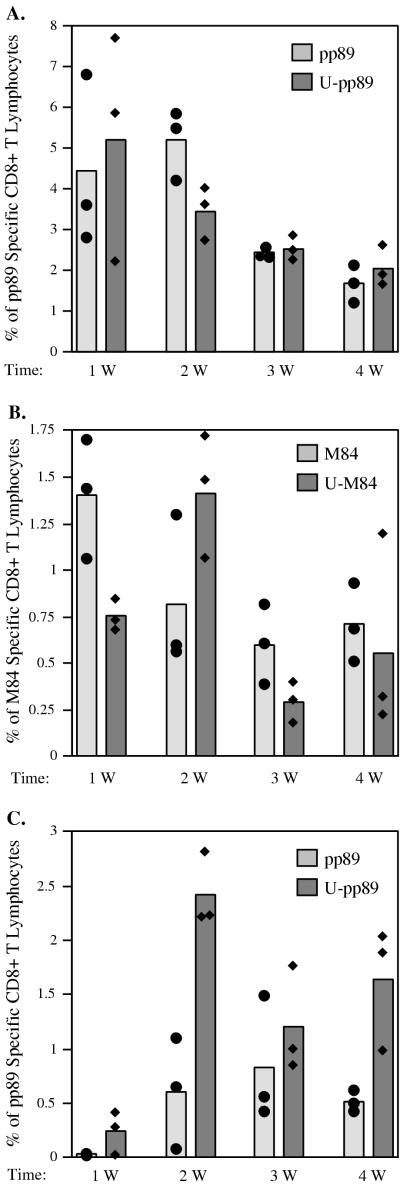

Previously, it was reported that addition of a ubiquitin moiety to the influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) did not affect its stability, and immunization of mice with 10 μg of the construct expressing the ubiquitin fusion protein did not enhance the immune response (9). However, when 10-fold-lower levels of DNA were used for the immunization, the construct expressing the NP-ubiquitin fusion protein generated CTLs that gave a higher percentage of lysis in cytotoxicity assays. In addition, the anti-NP antibody responses were greatly reduced in mice immunized with the ubiquitin-NP construct from those in mice immunized with wild-type NP. We, therefore, proceeded to investigate the effects of ubiquitin modification of pp89 and M84 on the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response. Groups of mice in experiments 1 and 2 described for Fig. 1B were injected i.d. with DNA expressing ubiquitinated pp89 (experiment 1) or ubiquitinated M84 (experiment 2), and the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses to the DNA vectors were compared. We found that when mice were immunized three times with 10 μg of plasmids expressing pp89 or ubiquitinated-pp89, the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses against the epitope of pp89 were induced to the same level with approximately the same kinetics (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

(A and B) BALB/c mice were either immunized three times with 10 μg of pc3-Ua, pc3-pp89 (pp89), or pc3-U-pp89 (U-pp89) (A) or with 10 μg of pc3-Ua, pc3-M84 (M84), or pc3-U-M84 (U-M84) (B) over a 20-day period as described for Fig. 1, experiments 1 and 2, respectively. (C) BALB/c mice were immunized only once with 10 μg of pc3-U, pc3-pp89 (pp89), or pc3-U-pp89 (U-pp89). At 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks (W) after the last immunization, CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the pp89 peptide (A and C) or the M84 peptide (B) in the spleen were measured by ICCS as described in Materials and Methods. Background values detected in mice immunized with pc3-U were subtracted from the values for mice immunized with DNA vaccines. Bars represent average values for three mice; solid symbols represent values obtained for individual mice.

When we repeated the above experiments with M84, we found that following immunization with three doses of 10 μg of DNA expressing M84 or ubiquitinated M84, the peak levels of CD8+ T lymphocytes generated against the M84 epitope were also comparable. However, the kinetics of the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were slightly different. The peak CD8+ T-lymphocyte response after M84 DNA immunization was reached at the end of the 1st week, while that following ubiquitinated M84 DNA immunization was observed a week later (Fig. 4B).

To determine whether immunization with a vector expressing the ubiquitinated protein might be different under conditions where vaccination was suboptimal, we also immunized mice with only a single dose of 10 μg of the DNA expressing pp89 or ubiquitinated pp89. As shown in Fig. 4C, CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were induced faster and reached a higher peak level with the pp89-ubiquitin fusion protein. In mice immunized only once with pc3-U-pp89 DNA, CD8+ T lymphocytes were detected at the end of the 1st week, peaked at the end of the 2nd week, and then dropped at the end of the 3rd week. At the end of week 4, the percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes resulting from immunization of mice with the DNA expressing ubiquitinated pp89 remained higher than that generated by the pp89 DNA and was comparable to that seen in mice immunized three times with plasmids expressing either pp89 or ubiquitinated pp89.

Taken together, the results indicate that after three DNA immunizations, the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were very similar for ubiquitinated and nonubiquitinated forms of pp89 and M84. However, when the immunization was suboptimal (i.e., after one dose of DNA vaccine), the fusion of the ubiquitin gene to the DNA coding for pp89 enhanced the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response.

Immunization with DNA encoding pp89 and M84 confers long-term immunity and protection against infection.

For a DNA vaccine to be successful, the immunological response and protection against subsequent infection must be reasonably strong and long-lasting. We therefore measured the levels of the secondary CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses and the titer of virus in the spleen following MCMV challenge in both short-term and long-term experiments.

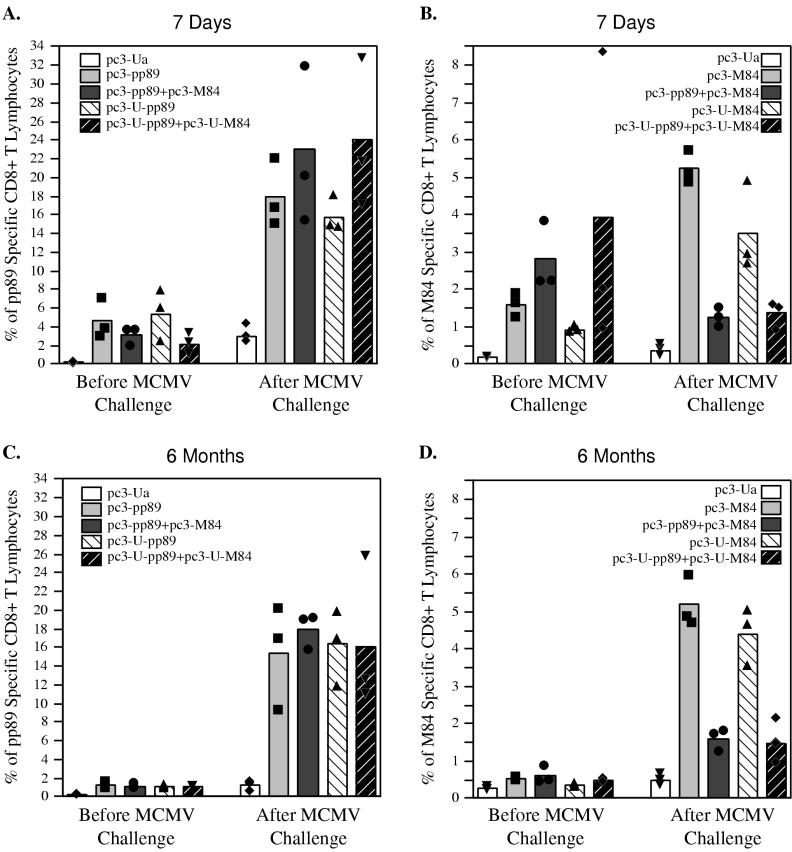

To determine the magnitude of the secondary immune response, mice were immunized three times with 10 μg of vector alone (pc3-Ua) or plasmids expressing pp89, ubiquitinated pp89 (U-pp89), M84, ubiquitinated M84(U-M84), pp89 plus M84, or ubiquitinated pp89 plus ubiquitinated M84; then they were challenged with salivary gland-derived MCMV 7 days (Fig. 5A and B) or 6 months (Fig. 5C and D) after the last immunization. The percentages of splenic CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for pp89 and M84 were assessed both on the day of challenge and 5 days after challenge with MCMV.

FIG. 5.

BALB/c mice were immunized three times either with 10 μg of vector alone (pc3-Ua) or plasmids expressing pp89 (pc3-pp89), ubiquitinated pp89 (pc3-U-pp89), pp89 plus M84 (pc3-pp89+pc3-M84), or ubiquitinated pp89 plus ubiquitinated M84 (pc3-U-pp89+pc3-U-M84) (A and C), as described for experiment 1 of Fig. 1, or with 10 μg of pc3-Ua, pc3-M84, pc3-U-M84, pc3-pp89+pc3-M84, or pc3-U-pp89+pc3-U-M84 (B and D), as described for experiment 2 of Fig 1. (A and B) Seven days after the last immunization, mice were challenged with 1.2 × 105 PFU (A) or 3 × 105 PFU (B) of salivary gland-derived MCMV. (C and D) Six months after the last immunization, mice were challenged with 2 × 105 PFU of salivary gland-derived MCMV. Amounts of pp89 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (A and C) and M84 peptide-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (B and D) in the spleen were determined by ICCS before MCMV challenge or 5 days after MCMV challenge. Bars represent average values for three mice; solid symbols represent values obtained from individual mice.

Figure 5A shows that at 7 days after the last immunization, levels of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the pp89 epitope were lower in mice coimmunized with plasmids expressing pp89 plus M84 than in mice immunized only with the plasmid expressing pp89, although the difference was not statistically significant. Similar results were also obtained when mice were immunized with the pp89 gene and M84 gene fused to ubiquitin, and in this case the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.04). After MCMV challenge, all of the groups showed similar pp89-specific CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses. The percentage of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the pp89 epitope increased an average of fivefold after challenge and constituted 16 to 23% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes. In some mice, the percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes rose as high as 32% after challenge. Since only 3% of the CD8+ T lymphocytes in the mice immunized with plasmid vector alone were pp89 specific after challenge, the large increase in the level of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the vaccinated mice was due to a secondary response.

In Fig. 5B, we show the CD8+ T-cell responses specific for the M84 epitope following immunization with M84 alone or coimmunization with M84 and pp89. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1, prior to the MCMV challenge, levels of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the M84 epitope were slightly higher in mice coimmunized with pp89 and M84 or their ubiquitinated forms than in mice immunized with M84 or ubiquitinated M84 alone, although these differences were not statistically significant. When the mice were challenged with MCMV 7 days after the last immunization, the percentages of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in mice immunized with M84 or ubiquitinated M84 alone reached an average of 4 to 5%, an increase of approximately three- to fourfold over the percentages detected prior to challenge. However, in mice coimmunized with pp89 and M84 or their ubiquitinated forms, the percentages of CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the M84 epitope decreased approximately twofold after challenge. Ubiquitination of the protein did not have a significant effect on the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response to the M84 epitope either before or after mice were challenged with MCMV. The reason for the observed bias of the secondary immune response toward the pp89 epitope over the M84 epitope in mice coimmunized with both pp89 and M84 remains to be elucidated. However, since pp89 is expressed earlier than M84 in the infected cells, this bias may be related to the relative order in which the two proteins are presented.

When the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses were examined 6 months after the last immunization, we found that approximately 1.2% of the CD8+ T lymphocytes in the spleen were specific for pp89 (Fig. 5C). These immune cells were able to expand rapidly in response to the challenge virus. Five days following challenge with MCMV, CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the pp89 epitope increased to approximately 16% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes in all four groups. In contrast, in pc3-Ua-immunized control mice, only 1.2% of spleen CD8+ T cells were pp89 epitope specific. Ubiquitination of the protein did not seem to have a significant effect on either the maintenance of the immune response after immunization or the secondary immune response after MCMV challenge.

The M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (approximately 0.2 to 0.4% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes) were also detectable 6 months after the last immunization (Fig. 5D). Although these levels were low, they were able to respond rapidly and vigorously to MCMV infection. Five days following challenge with MCMV, there was a strong secondary immune response. The pattern of these secondary immune responses was very similar to that observed in mice challenged with MCMV 7 days after the last immunization (Fig. 5B). In mice immunized with M84 or ubiquitinated M84 plasmids alone, M84 epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes increased to 5% of spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes. Mice immunized with vector alone induced an average of only 0.5% M84 epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes. Moreover, when mice were coimmunized with pp89 and M84 with or without ubiquitin modification and challenged with MCMV 6 months later, there was an increase in the percentage of M84 epitope-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated, but the values were approximately three- to fourfold lower than those obtained for mice immunized with the M84 or ubiquitinated M84 plasmid alone.

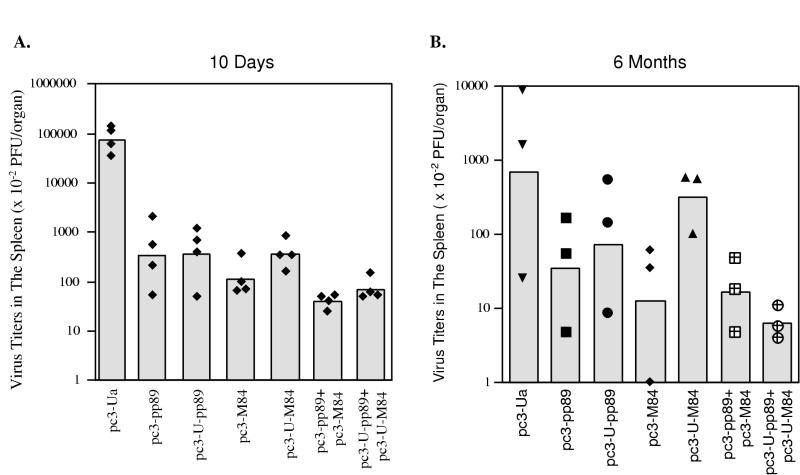

As a complement to the above experiments, we assessed the levels of both short-term and long-term protection against subsequent MCMV infection that were elicited by DNA vaccination. Mice were immunized as above with 10 μg of the DNA plasmids; then, 10 days (Fig. 6A) or 6 months (Fig. 6B) after the last immunization, they were challenged i.p. with salivary gland-derived MCMV. Spleens were harvested 5 days later, and virus titers were measured by standard plaque assay. As shown in Fig. 6A, when mice were challenged 10 days after the last immunization, the best protection was observed in the groups coimmunized with both the pp89 and M84 vaccines. Regardless of whether mice were immunized with pp89 or M84 separately or coimmunized, ubiquitination of the proteins had no significant effect on protection.

FIG. 6.

BALB/c mice were immunized three times with 10 μg of vector alone (pc3-Ua) or plasmids expressing pp89 (pc3-pp89), ubiquitinated pp89 (pc3-U-pp89), M84 (pc3-M84), ubiquitinated M84 (pc3-U-M84), pp89 plus M84 (pc3-pp89+pc3-M84), or ubiquitinated pp89 plus ubiquitinated M84 (pc3-U-pp89+pc3-U-M84) over a 20-day period. Ten days (A) or 6 months (B) later, immunized mice were i.p. challenged with 1.2 × 105 PFU* or 2 × 105 PFU of salivary gland-derived MCMV, respectively. Five days after the challenge, the titer of virus in each spleen was determined by standard plaque assay as described in Materials and Methods. The sensitivity of the plaque assay was 100 PFU/spleen. Bars represent geometric averages of virus titers of four mice (A) or three mice (B). Solid symbols represent titers for individual mice. ∗, a different stock of salivary gland-derived virus was used in the experiment for which results are shown in panel A (see Materials and Methods).

Figure 6B shows that 6 months after the last immunization, mice were still protected against infection, although there was considerable variability in the titers for individual mice within a group. Because one mouse in the control group had an unusually low titer of virus in the spleen, it was not possible to document that the differences between the groups were statistically significant by ANOVA. In this experiment, the CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses shown in Fig. 5C and D were determined by using mice from the same groups that were used for the determination of virus titers in the spleen. It should be noted that a different stock of MCMV was used in this long-term protection experiment, and thus the overall titers in the spleen were lower than those observed in Fig. 6A. As was observed when mice were challenged shortly after immunization, mice coimmunized with pp89 and M84 with or without ubiquitin modification had the highest level of protection against MCMV replication in the spleen. Virus titers were reduced approximately 43-fold in mice coimmunized with pp89 plus M84 and 112-fold in mice coimmunized with ubiquitinated pp89 plus ubiquitinated M84. In mice immunized with pp89 or ubiquitinated pp89 alone, we detected a 20- or 10-fold reduction, respectively, in spleen virus titers compared with mice immunized with vector only. Mice immunized with the M84 plasmid also showed significant protection against infection, with spleen virus titers reduced approximately 55-fold. In one mouse, the spleen titer was at the limit of detection. In this experiment, however, ubiquitinated M84 seemed to provide much less long-term protection than M84, as there was only a two- to threefold reduction in spleen virus titers. These results demonstrate that immunization of mice with 10 μg of plasmids coding for MCMV pp89 and M84 confers long-term immunity as measured by both the levels of specific CD8+ T lymphocytes and the resulting protection against subsequent MCMV challenge.

DISCUSSION

The efficacy of a vaccine is usually evaluated by two parameters: the magnitude of protection against disease and the strength of the immune responses. In the past, we successfully demonstrated that three i.d. immunizations of mice with DNA constructs expressing pp89 and M84 protected them against subsequent lethal and sublethal viral challenge 10 days after the last injection (10, 24). Similar results were obtained in the experiments presented here. At the challenge dose used in the present experiments, the levels of protection after pp89 or M84 immunization were very similar. These results were consistent with earlier findings that pp89 and M84 were equally protective when the amount of virus used for challenge was below 0.5 LD50. If a higher dose of virus was used for challenge, however, pp89 DNA immunization usually provided better protection than did M84 DNA(24). Because the higher viral challenge usually leads to significant destruction of the spleens in nonprotected mice and compromises analysis of the immune response in the spleen, we routinely used a virus dose at or below 0.5 LD50.

To measure long-term protection, we challenged the mice with MCMV 6 months after they were immunized three times with pp89 and/or M84 DNA. We were very encouraged to find that mice immunized with MCMV DNA vectors had lower titers of virus in the spleen than those immunized with vector only. As in the short-term experiments, the best protection was observed in mice coimmunized with both pp89 and M84. Although the extent of protection as measured by reduction of spleen titers following challenge declined relative to the protection observed in the short-term experiments, immunity was still robust, and high levels of pp89- and M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes were present in the spleen. These long-term memory cells were also very responsive to the subsequent virus challenge, as evidenced by the rapid 10-fold increase in the percentage of pp89- or M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes. One difference that was noted in the mice that were challenged after 6 months, however, was that the titers of virus in the spleen, even in those mice that were immunized with vector only, showed greater variability. Whether this is due to enhanced innate or adaptive immune responses to MCMV in the older mice remains to be determined.

In another murine model in which a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) DNA vaccine was tested, better protection and better immune responses were achieved when one of the vaccine candidates was modified by fusing the gene coding for ubiquitin to the amino terminus of the LCMV sequence (31, 33). We similarly fused the ubiquitin gene to the ends of the pp89 and M84 genes corresponding to the amino termini. In general, there were no significant differences in the short-term or long-term immune responses and protection generated with the ubiquitinated versus the nonubiquitinated pp89 or M84 vector. We did note, however, that when mice were immunized with pp89 or ubiquitinated pp89 only once, the percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated was higher with the ubiquitinated pp89 DNA (Fig. 4C). In addition, very little long-term protection was provided by immunization with the ubiquitinated M84 vector.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of a significant adjuvant effect when ubiquitin was fused to the MCMV pp89 and M84 genes. One possibility may be related to the intrinsic differences in the immune responses following immunization with the LCMV DNA versus the MCMV DNA. It has been reported that during LCMV infection of BALB/c mice, CD8+ T lymphocytes specific for the dominant epitope NP118-126 accounted for more than 50% of total spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes (25, 34). However, when the mice were immunized once with the plasmid expressing LCMV NP protein, only 0.7% of the spleen CD8+ T lymphocytes were NP specific at the peak level (13). Therefore, the level of CD8+ T cells after DNA immunization was significantly lower than that after LCMV infection. In contrast, three DNA immunizations with the MCMV pp89 vector elicited the same number of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes (up to 6% of total CD8+ T lymphocytes) as did MCMV infection. Moreover, the level of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes generated by DNA immunization was significantly higher than that following MCMV infection (1.4 versus 0.25%). Therefore, the immune responses after vaccination with the pp89 and M84 plasmids may have already approached the maximal level. This is consistent with our finding that a higher percentage of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes was generated with the ubiquitinated pp89 DNA when the DNA was injected only once (Fig. 4C).

Another possibility is that the immune response was not enhanced because expression of M84 and pp89 as ubiquitin fusion proteins did not decrease their stability, at least as measured in the transient expression assays. In the case of the LCMV NP protein, ubiquitination significantly reduced the stability of the protein in transient assays (33). However, decreased stability of the ubiquitinated protein does not always correlate with enhanced immune response. On example is the work of Delogu et al. (5), who found that although the ubiquitinated form of the tuberculosis protein MPT64 was less stable, DNA immunization with a vector expressing the fusion protein did not increase the immune response or protection against mycobacterium. Fu et al. (9) also showed that modification of the influenza virus NP protein with ubiquitin did not decrease its stability in transient assays or enhance the immune response when 10 μg of DNA was injected. However, in agreement with the work presented here, when less DNA was used for immunization, the ubiquitinated NP protein did elicit a somewhat stronger immune response than the NP protein itself.

As noted above, the level of pp89-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the DNA-immunized mice was very similar to that in the MCMV-infected mice. In contrast, the overall level of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the DNA-immunized mice was significantly higher than that in mice infected with MCMV, although there was variability in the values for individual mice. After three immunizations, the percentage of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes ranged from 0.8 to 4% of total CD8+ T lymphocytes. In mice infected with either 4 × 104 (data not shown) or 1.2 × 105 PFU of MCMV, the peak level of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes was usually no higher than 0.4%, and 2 weeks later, the level of the immune cells dropped below the limit of detection. Holtappels et al. (14, 17) also documented, by using an IFN-γ-based ex vivo ELISpot assay, that the peak level of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes was very low after MCMV infection and had decreased below the limit of detection when the CD8+ T lymphocytes were examined 1 month later. One reason for the minimal CTL response against M84 during MCMV infection is that it is likely that many other Kd-restricted epitopes are generated during infection, all of which compete with M84 for presentation to the CTLs. These results demonstrate that during virus infection, a minor or cryptic antigen may actually elicit a vigorous immune response and provide strong protection when administered by DNA vaccination. Other evidence for this is provided by a recent report showing that a minor antigen during LCMV infection was also a good DNA vaccine candidate (32).

One interesting finding was that although pp89 is a dominant antigen and the percentage of specific CD8+ T lymphocytes elicited was approximately three- to fourfold higher for the pp89 epitope than for the M84 epitope when the DNA vectors were tested individually, similar percentages of pp89- and M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes were detected when mice were coimmunized with both vectors. These results differ from what has been observed with both the LCMV NP protein and the influenza virus NP protein, which contain dominant and subdominant epitopes. In both cases DNA immunization with a vector expressing the wild-type protein elicited an immune response only to the dominant epitope. However, when the dominant epitope was mutated, an immune response to the subdominant epitope was induced that was protective against LCMV infection (8, 32). Since the dominant and subdominant epitopes are on the same protein in the cases of the LCMV and influenza virus NP proteins, it is possible that a conformational change in the protein might have been responsible for the higher response elicited against the subdominant epitope when the DNA expressing the mutant protein was used as a vaccine. It would be interesting to determine whether similar immune responses to these subdominant epitopes would be induced if mice were coimmunized with both wild-type NP and mutant NP DNA. This would be similar to the situation with pp89 and M84, where the subdominant and dominant epitopes are on different proteins.

A striking difference in the secondary CD8+ T-lymphocyte response to pp89 and M84 was also observed in mice injected with one DNA vector versus both vectors after the mice were challenged with MCMV. In both the singly immunized and coimmunized mice, the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response to pp89 increased more than fivefold following MCMV challenge. In contrast, following MCMV challenge, there was an increase in the percentage of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes only in mice immunized with the M84 DNA alone. In fact, when the mice were assessed for short-term secondary responses, the percentage of M84-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes decreased slightly following MCMV challenge. These results indicate that the ability of a subdominant CD8+ T-cell epitope to elicit a recall response is suppressed by the dominant epitope. It is also possible that pp89 has some advantage because it is expressed earlier during MCMV infection than M84 (14, 17).

The direct inoculation of plasmid DNA into animal tissues is an exciting approach to vaccination that overcomes many of the problems associated with traditional immunization methods involving virus-based vectors or proteins (for a recent review, see reference 11). For example, the risks of using an attenuated live vaccine are avoided because plasmid DNA is free of infectious agents. In addition, because there is little or no immune response to plasmid DNA, the vector can be used for subsequent immunizations. Moreover, large quantities of plasmid DNA can be made at minimal cost, and the DNA is highly stable. Major advantages of DNA vaccines are that they engender both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses and that it is relatively easy to manipulate the DNA to change the immune response both qualitatively and quantitatively. Nevertheless, this field still contains a great deal of uncharted territory, and there is much to learn regarding the mechanisms underlying the induction of immune responses by DNA vaccines and the strategies to use for improving the efficacy of these vaccines. As discussed above, there may be significant differences in both the primary and secondary responses to a specific antigen when the DNA vaccines contain more than one gene. The correlation of immune response with protection may also be difficult to predict based solely on the levels of specific CD8+ lymphocytes elicited by vaccination or during acute infection. In addition, as shown in this study and in the work published by Holtappels et al. (14), the CD8+ T-lymphocyte response to M84 during acute infection is barely above background levels. Yet, following M84 DNA vaccination, the protection generated is comparable to that elicited by the dominant antigen pp89. At this time, the actual beneficial effects of DNA immunization can be determined only in trials where the immunized animals, and ultimately humans, are challenged with live virus.

Acknowledgments

We thankfully acknowledge the assistance of Daniel Hassett and Vladimir Badovinac in establishing the ICCS assay. We thank the members of our laboratory for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by research grant 6-FY99-442 from the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation and by NIH training grant T32 AI07036.

REFERENCES

- 1.Badovinac, V. P., and J. T. Harty. 2000. Intracellular staining for TNF and IFN detects different frequencies of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. Methods 238:101-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt, W., and C. Alford. 1996. Cytomegalovirus, p. 2493-2523. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 3.Britt, W. J., L. Vugler, E. J. Butfiloski, and E. B. Stephens. 1990. Cell surface expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gp55-116 (gB): use of HCMV-recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in analysis of the human neutralizing antibody response. J. Virol. 64:1079-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cranmer, L. D., C. L. Clark, C. S. Morello, H. E. Farrell, W. D. Rawlinson, and D. H. Spector. 1996. Identification, analysis, and evolutionary relationship of the putative murine cytomegalovirus homologues of the human cytomegalovirus UL82 (pp71) and UL83 (pp65) matrix phosphoproteins. J. Virol. 70:7929-7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delogu, G., A. Howard, F. M. Collins, and S. L. Morris. 2000. DNA vaccination against tuberculosis: expression of a ubiquitin-conjugated tuberculosis protein enhances antimycobacterial immunity. Infect. Immun. 68:3097-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Del Val, M., H.-J. Schlicht, H. Volkmer, M. Messerle, M. J. Reddehase, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1991. Protection against lethal cytomegalovirus infection by a recombinant vaccine containing a single nonameric T-cell epitope. J. Virol. 65:3641-3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler, K. B., S. Stagno, R. F. Pass, W. J. Britt, T. J. Boll, and C. A. Alford. 1992. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N. Engl. J. Med. 326:663-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu, T., A. Friedman, J. B. Ulmer, M. A. Liu, and J. J. Donnelly. 1997. Protective cellular immunity: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses against dominant and recessive epitopes of influenza virus nucleoprotein induced by DNA immunization. J. Virol. 71:2715-2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu, T., L. Guan, A. Friedman, J. B. Ulmer, M. A. Liu, and J. J. Donnelly. 1998. Induction of MHC class I-restricted CTL response by DNA immunization with ubiquitin-influenza virus nucleoprotein fusion antigens. Vaccine 16:1711-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Armas, J. C., C. S. Morello, L. D. Cranmer, and D. H. Spector. 1996. DNA immunization confers protection against murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 70:7921-7928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurunathan, S., D. M. Klinman, and R. A. Seder. 2000. DNA vaccines: immunology, application, and optimization. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:927-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassett, D. E., M. K. Slifka, J. Zhang, and J. L. Whitton. 2000. Direct ex vivo kinetic and phenotypic analyses of CD8+ T-cell responses induced by DNA immunization. J. Virol. 74:8286-8291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassett, D. E., J. Zhang, M. Slifka, and J. L. Whitton. 2000. Immune responses following neonatal DNA vaccination are long-lived, abundant, and qualitatively similar to those induced by conventional immunization. J. Virol. 74:2620-2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holtappels, R., J. Podlech, N. K. A. Grzimek, D. Thomas, M.-F. Pahl-Seibert, and M. J. Reddehase. 2001. Experimental preemptive immunotherapy of murine cytomegalovirus disease with CD8 T-cell lines specific for ppM83 and pM84, the two homologs of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein ppUL83 (pp65). J. Virol. 75:6584-6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtappels, R., J. Podlech, G. Geginat, H. P. Steffens, D. Thomas, and M. J. Reddehase. 1998. Control of murine cytomegalovirus in the lungs: relative but not absolute immunodominance of the immediate-early 1 nonapeptide during the antiviral cytolytic T-lymphocyte response in pulmonary infiltrates. J. Virol. 72:7201-7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtappels, R., D. Thomas, J. Podlech, G. Geginat, H. P. Steffens, and M. J. Reddehase. 2000. The putative natural killer decoy early gene m04 (gp34) of murine cytomegalovirus encodes an antigenic peptide recognized by protective antiviral CD8 T cells. J. Virol. 74:1871-1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtappels, R., D. Thomas, and M. J. Reddehase. 2000. Identification of a Kd-restricted antigenic peptide encoded by murine cytomegalovirus early gene M84. J. Gen. Virol. 81:3037-3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonjic, S., I. Pavic, P. Lucin, D. Rukavina, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1989. Site-restricted persistent cytomegalovirus infection after selective long-term depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 169:1199-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonjic, S., M. Del Val, G. M. Keil, M. J. Reddehase, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1988. A nonstructural viral protein expressed by a recombinant vaccinia virus protects against lethal cytomegalovirus infection. J. Virol. 62:1653-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonjic, S., I. Pavic, P. Lucin, D. Rukavina, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1990. Efficacious control of cytomegalovirus infection after long term depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Virol. 64:5457-5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleijnen, M. F., J. B. Huppa, P. Lucin, S. Mukherjee, H. Farrell, A. E. Campbell, U. H. Koszinowski, A. B. Hill, and H. L. Ploegh. 1997. A mouse cytomegalovirus glycoprotein, gp34, forms a complex with folded class I MHC molecules in the ER which is not retained but is transported to the cell surface. EMBO J. 16:685-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall, G. S., G. P. Rabalais, and S. L. Waldeyer. 1992. Antibodies to recombinant-derived glycoprotein B after natural human cytomegalovirus infection correlate with neutralizing activity. J. Infect. Dis. 165:381-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morello, C. S., L. D. Cranmer, and D. H. Spector. 1999. In vivo replication, latency, and immunogenicity of murine cytomegalovirus mutants with deletions in the M83 and M84 genes, the putative homologs of human cytomegalovirus pp65 (UL83). J. Virol. 73:7678-7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morello, C. S., L. D. Cranmer, and D. H. Spector. 2000. Suppression of murine cytomegalovirus replication with a DNA vaccine encoding the MCMV early nonstructural protein M84 (a homolog of human cytomegalovirus pp65). J. Virol. 74:3696-3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murali-Krishna, K., J. D. Altman, M. Suresh, D. J. D. Sourdive, A. J. Zajac, J. D. Miller, J. Slansky, and R. Ahmed. 1998. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 8:177-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podlech, J., R. Holtappels, N. Wirtz, H.-P. Steffens, and M. J. Reddehase. 1998. Reconstitution of CD8 T cells is essential for the prevention of multiple-organ cytomegalovirus histopathology after bone marrow transplantation. J. Gen. Virol. 79:2099-2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rapp, M., M. Messerle, P. Lucin, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1993. In vivo protection studies with MCMV glycoproteins gB and gH expressed by vaccinia virus, p. 327-332. In P. S. A. Michelsons (ed.), Multidisciplinary approach to understanding cytomegalovirus disease. Excerpta Medica, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 28.Rasmussen, L. E., R. M. Nelson, D. C. Kelsall, and T. C. Merigan. 1984. Murine monoclonal antibody to a single protein neutralizes the infectivity of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:876-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddehase, M. J., and U. H. Koszinowski. 1984. Significance of herpesvirus immediate early gene expression in cellular immunity to cytomegalovirus infection. Nature 312:369-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddehase, M. J., J. B. Rothbard, and U. H. Koszinowski. 1989. A pentapeptide as minimal antigenic determinant for MHC class I-restricted T lymphocytes. Nature 337:651-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez, F., L. L. An, S. Harkins, J. Zhang, M. Yokoyama, G. Widera, J. T. Fuller, C. Kincaid, I. L. Campbell, and J. L. Whitton. 1998. DNA immunization with minigenes: low frequency of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes and inefficient antiviral protection are rectified by ubiquitination. J. Virol. 72:5174-5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodriguez, F., M. K. Slifka, S. Harkins, and J. L. Whitton. 2001. Two overlapping subdominant epitopes identified by DNA immunization induce protective CD8+ T-cell populations with differing cytolytic activities. J. Virol. 75:7399-7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez, F., J. Zhang, and J. L. Whitton. 1997. DNA immunization: ubiquitination of a viral protein enhances cytotoxic T-lymphocyte induction and antiviral protection but abrogates antibody induction. J. Virol. 71:8497-8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slifka, M. K., F. Rodriguez, and J. L. Whitton. 1999. Rapid on/off cycling of cytokine production by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Nature 401:76-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steffens, H.-P., S. Kurz, R. Holtappels, and M. J. Reddehase. 1998. Preemptive CD8 T-cell immunotherapy of acute cytomegalovirus infection prevents lethal disease, limits the burden of latent viral genomes, and reduces the risk of virus recurrence. J. Virol. 72:1792-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeager, A. S., F. C. Grumet, E. B. Hafleigh, A. M. Arvin, J. E. Bradley, and C. G. Prober. 1981. Prevention of transfusion-acquired cytomegalovirus infection in newborn infants. J. Pediatr. 988:1189-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]