Abstract

The virulence genotype profile and presence of a pathogenicity island(s) (PAI) were studied in 18 strains of F165-positive Escherichia coli originally isolated from diseased calves or piglets. On the basis of their adhesion phenotypes and genotypes, these extraintestinal pathogenic strains were classified into three groups. The F165 fimbrial complex consists of at least two serologically and genetically distinct fimbriae: F1651 and F1652. F1651 is encoded by the foo operon (pap-like), and F1652 is encoded by fot (sfa related). Strains in group 1 were foo and fot positive, strains in group 2 were foo and afa positive, and strains in group 3 were foo positive only. The strains were tested for the presence of virulence genes found mainly in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) strains. Although all the strains were positive for the papA variant encoding F11 fimbriae incD, traT, and papC, the prevalence of virulence genes commonly found in PAIs associated with ExPEC strains was highly variable, with strains of group 2 harboring most of the virulence genes tested. papG allele III was detected in all strains in group 1 and in one strain in group 3. All other strains were negative for the known alleles encoding PapG adhesins. The association of virulence genes with tRNA genes was characterized in these strains by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and DNA hybridization. The insertion site of the foo operon was found at the pheU tRNA locus in 16 of the 18 strains and at the selC tRNA locus in the other 2 strains. Furthermore, 8 of the 18 strains harbored a high-pathogenicity island which was inserted in either the asnT or the asnV/U tRNA locus. These results suggest the presence of one or more PAIs in septicemic strains from animals and the association of the foo operon with at least one of these islands. F165-positive strains share certain virulence traits with ExPEC, and most of them are pathogenic in piglets, as tested in experimental infections.

Escherichia coli is a frequent cause of intestinal and extraintestinal diseases in humans and animals. Typical extraintestinal infections include urinary tract infections, newborn meningitis, polyserositis, and septicemia. All these groups of pathogenic E. coli strains have been called extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC). The recognized virulence factors of ExPEC include diverse adhesins (e.g., P fimbriae, S/F1C fimbriae, F165 fimbriae, Afa/Dr adhesins, and type 1 fimbriae), toxins (e.g., hemolysin, cytotoxic necrotizing factor, and cytolethal distending toxin), surface antigens (e.g., group II and group III capsules and lipopolysaccharide), invasins (e.g., an invasin responsible for invasion of brain endothelium [IbeA, also called Ibe10]), iron uptake systems (e.g., the aerobactin system), and secretion systems (e.g., type III secretion systems). These virulence factors facilitate colonization and invasion of the host, avoidance or disruption of host defense mechanisms, injury to host tissues, and/or stimulation of a noxious host inflammatory response (34, 50).

Fimbrial antigen complex F165, which exhibits mannose-resistant hemagglutination, is found mostly on E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with septicemia and/or diarrhea (19) and from humans with septicemia (11). Most F165-positive E. coli isolates are not enterotoxigenic or hemolytic; produce aerobactin; are resistant to the bactericidal effects of serum; do not produce verotoxin; and are negative for fimbrial antigens F4, F5, F41, and F6 (24). However, most F165-positive isolates, whether of intestinal or extraintestinal origin, induce septicemia and polyserositis but rarely induce diarrhea or significant enteric lesions in experimentally infected newborn piglets (17, 18). The F165 fimbrial complex consists of at least two serologically and genetically distinct fimbriae: F1651 and F1652 (23, 25). The F1651A major fimbrial subunit of F165, which is encoded by the foo operon, is closely related to that of P fimbriae of serotype F11 but bears a class III G adhesin similar to the P-related (Prs) adhesin of F13 fimbriae, with specificity for the galactose-N-acetyl-α-(1-3)-galactose-N-acetyl (GalNac-GalNac) moiety (17, 40). F1652 fimbriae, which are encoded by the fot operon, are closely related to F1C fimbriae (26). F165-positive strains possess many of the attributes of ExPEC strains that cause septicemia.

Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), which are large clusters of virulence genes in the bacterial chromosome, have been identified in many different bacterial pathogens (22). The PAIs of uropathogenic (UPEC) human strains were the first to be described in E. coli. At least four PAIs are present in the genome of UPEC strain 536. PAI I536, inserted next to the selC tRNA locus, and PAI II536, inserted next to the leuX tRNA locus, respectively encode the hemolysin and the Prs fimbrial adhesin. On the other hand, PAI III536 is inserted next to the thrW tRNA locus and encodes the S fimbrial adhesin (14). PAI IV536 is inserted next to the asnT tRNA locus and carries the fyuA (ferrin yersiniabactin uptake) and irp1 (iron-repressible protein) through irp5 genes originally found in the high-pathogenicity islands (HPIs) of various Yersinia species (10). Two PAIs were described in UPEC strain J96 and encode the hemolysin and P or Prs fimbrial adhesins. They are PAI IJ96, which is inserted next to the pheV tRNA locus, and PAI IIJ96, which also encodes cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 and which is inserted next to the phenylalanine-specific pheR (also known as pheU) tRNA locus (22).

The population structure of E. coli, as represented by the E. coli reference (ECOR) collection (46), is thought to be clonal, since it comprises four major clonal groups called A, B1, B2, and D (28). Most ExPEC isolates belong to ECOR group B2 and, to a lesser extent, ECOR group D (5). Recently, it was shown that ECOR group B2 and D strains more often carry certain virulence genes, including hly, pap, sfa, and kps, than strains from the other ECOR groups (8). These studies suggest that a cluster of E. coli strains acquired virulence genes by horizontal transfer, thus defining a highly virulent group. The link between the B2 phylogenetic group and virulence in ExPEC was recently confirmed in studies with experimentally infected mice (48). In this study we have found that F165-positive strains from pigs and calves share virulence genes found in ExPEC strains and that one or more PAIs are present. Certain virulence attributes found in F165 strains can be associated with pathogenicity, as tested in our model. Although F165-positive strains have been isolated from clinical cases, they belong to the groups, according to the phylogenetic scheme proposed by other investigators (13, 24, 28), that are less virulent than human ExPEC strains. Moreover, the ExPEC genes of animal F165-positive E. coli strains were characterized for their relationship with PAIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The 18 F165-positive E. coli isolates used in this study were obtained from the Escherichia coli Laboratory of the Faculté de Médecine Vétérinaire, Université de Montréal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec, Canada. These isolates were originally isolated from calves or piglets and were isolated either from the intestines of animals with septicemia or from extraintestinal tissues of animals with septicemia. All isolates were from different animals and farms. Other strains and/or plasmids used as controls for assay development included E. coli strains MG1655, 536 (fyuA irp1 irp2), CFT073, and J96 (papA papC papG alleles I and III sfa/foc fimA kpsMT III hlyC cnf1); E. coli O157:H7 (E-hlyA espP etpD katP); Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32637 (for detection of the FyuA protein); and E. coli strains IA2 (papG allele II), CS31A (clpG f17c-A), JM109/pAH1010 (nfa allele I), pKT107 (traT), HB101/pILL 1194 (afa-7), and HB101/pILL 1224 (afa-8). The strains were stored at −70°C in Luria broth plus 15% glycerol until they were ready for use. The E. coli strains were routinely grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with shaking at 37°C.

Detection of virulence genes and rapid phylogenetic analysis by PCR.

The primers used for amplification of the virulence genes were derived from different sources or were designed from available nucleotide sequences (Table 1). All strains were tested for the presence of the three alleles of papG and 11 variants of papA by established specific PCR assays (30, 36). The virulence determinants examined in this work were chosen because of their association with E. coli strains causing extraintestinal infections. The strains were screened for PCR products specific for genes encoding adhesins: P (pap), S/F1C (sfa), type 1 (fimA), F17c (f17c-A), and Afa/Dr (afa) adhesins; M blood group antigen-specific M fimbriae (bma); nonfimbrial adhesin type 1 (nfa); and Iha (iha) nonhemagglutinating adhesin (55). The toxin genes screened for were those encoding alpha-hemolysin (hly), cnf, and E-hlyA (53) and cdtB (cytolethal distending toxin) (34). The siderophore systems screened for included aerobactin (iucD), yersiniabactin (fyuA), and iroNE. coli, a novel catechol siderophore receptor (33). The cvaC gene, which encodes colicin V (34), and the iss and traT genes, which encode proteins that increase resistance to serum (6, 12), were included in this study, as were other genes found in ExPEC, such as the gene for invasion of brain endothelium (ibeA or ibe10) (34) and capsular polysaccharide synthesis genes kpsMT II (e.g., K1, K5, and K12) and kpsMT III (e.g., K10 and K54) (34). Proteases encoding the ompT (outer membrane protein T), tsh (15), and espP (53) genes were also included in the study.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers and conditions used in this study

| Gene | Primer pair (5′-3′)a | Annealing temp (°C) | Predicted size (bp) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| papC | F GACGGCTGTACTGCAGGGTGTGGCG | 60 | 328 | 39 |

| R. ATATCCTTTCTGCAGGGATGCAATA | ||||

| sfaDE | F CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA | 60 | 410 | 39 |

| R. CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC | ||||

| afaBC III | F GCTGGGCAGCAAACTGATAACTCTC | 60 | 793 | 39 |

| R CATCAAGCTGTTTGTTCGTCCGCCG | ||||

| afaE-7 | F GCTAAATCAACTGTTGATGTT | 65 | 618 | 38 |

| R. GGACAATCCAAATGGCGAATTA | ||||

| afaE-8 | F CTAACTTGCCATGCTGTGACAGTA | 65 | 302 | 38 |

| R. TTATCCCCTGCGTAGTTGTGAATC | ||||

| clpG | F. GGGCGCTTCTCTCCTTCAAC | 55 | 402 | 4 |

| R CGCCCTAATTGCTGGCGAC | ||||

| 20K (f17c-A) | F GCAGAAAATTCAATTTATCCTTGG | 55 | 537 | 4 |

| R CTGATAAGCGATGGTGTAATTAAC | ||||

| fimA | fimA05 GTTGATCAAACCGTTCAG | 55 | 331 | 42 |

| fimA16 AATAACGCGCCTGGAACG | ||||

| bmaE | F ATGGCGCTAACTTGCCATGCTG | 60 | 507 | 34 |

| R AGGGGGACATATAGCCCCCTTC | ||||

| nfaE | F GCTTACTGATTCTGGGATGGA | 60 | 559 | 34 |

| R CGGTGGCCGAGTCATATGCCA | ||||

| iha | F. CTGGCGGAGGCTCTGAGATCA | 55 | 827 | 33 |

| R TCCTTAAGCTCCCGCGGCTGA | ||||

| iucD | F AAGTGTCGATTTTATTGGTGTA | 60 | 760 | 27 |

| R CCATCCGATGTCAGTTTTCTG | ||||

| fyuA | FyuA. 1A. GGCGGCGTGCGCTTCTCGCA | 60 | 209 | 1 |

| FyuArp CGCAGTAGGCACGATGTTGTA | ||||

| irp1 | F GCGATGTTTAACCCCGATT | 55 | 1,691 | 1 |

| R TGCCTGGAAACCCTGAGACT | ||||

| irp2 | Irp2. 15: GTTGCTGTCCATCAAGCACG | 60 | 1,243 | 1 |

| Irp2. 18 GCCGGAAAGCCTGGCCTTTA | ||||

| iroN | F AAGTCAAAGCAGGGGTTGCCCG | 55 | 665 | 33 |

| R GACGCCGACATTAAGACGCAG | ||||

| kpsMT II | F GCGCATTTGCTGATACTGTTG | 60 | 272 | 34 |

| R CATCCAGACGATAAGCATGAGCA | ||||

| kpsMT III | F TCCTCTTGCTACTATTCCCCCT | 60 | 392 | 34 |

| R AGGCGTATCCATCCCTCCTAAC | ||||

| traT | F GGTGTGGTGCGATGAGCACAG | 60 | 290 | 34 |

| R CACGGTTCAGCCATCCCTGAG | ||||

| iss | F TCACATAGGATTCTGCCG | 50 | 607 | This study |

| R AGAAATCAAAAGGTGGCC | ||||

| cvaC | F CACACACAAACGGGAGCTGTT | 55 | 680 | 34 |

| R CTTCCCGCAGCATAGTTCCAT | ||||

| ompT | ompt-f ATCTAGCCGAAGAAGGAGGC | 60 | 559 | 32 |

| omp-r CCCGGGTCATAGTGTTCATC | ||||

| espP | esp-A AAACAGCAGGCACTTGAACG | 56 | 1,830 | 9 |

| esp-B GGAGTCGTCAGTCAGTAGAT | /PICK> | |||

| ibe10 | F AGGCAGGTGTGCGCCGCGTAC | 60 | 170 | 34 |

| R TGGTGCTCCGGCAAACCATGC | ||||

| hlyC | F AGGTTCTTGGGCATGTATCCT | 60 | 556 | 5 |

| R TTGCTTTGCAGACTGCAGTGT | ||||

| E-hlyA | F GGTGCAGCAGAAAAAGTTGTAG | 57 | 1,551 | 52 |

| R TCTCGCCTGATAGTGTTTGGTA | ||||

| cnf | F TTATATAGTCGTCAAGATGGA | 50 | 636 | 47 |

| R CACTAAGCTTTACAATATTGAC | ||||

| tsh | tsh-1 GGTGGTGCACTGGAGTGG | 53 | 640 | 15 |

| tsh-2 AGTCCAGCGTGATAGTGG | ||||

| chuA | F GACGAACCAACGGTCAGGAT | 59 | 279 | 13 |

| R TGCCGCCAGTACCAAAGACA | ||||

| yjaA | F TGAAGTGTCAGGAGACGCTG | 59 | 211 | 13 |

| R ATGGAGAATGCGTTCCTCAAC | ||||

| TspE4 C2 | F GAGTAATGTCGGGGCATTCA | 59 | 152 | 13 |

| R CGCGCCAACAAAGTATTACG | ||||

| int | F TCCCTTACCGACGCAAAAATCC | 58 | 1,203 | 37 |

| R TGCTTCCAGATAATCCGACCAC | ||||

| asnT-int | IntSB ATCGCTTTGCGGGCTTCTAGGT | 60 | 1,393 | 1 |

| AsnTSB GAACGGCGGACTGTTAAT | ||||

| asnV-int | F GACAGCAAACAAACAAAAA | 60 | 1,500 | 37 |

| R TGCTTCCAGATAATCCGACCAC | ||||

| asnU-int | F TTTCGCTGTTAAGATGTGCC | 60 | 1,500 | 37 |

| R TGCTTCCAGATAATCCGACCAC | ||||

| IS100 | F ATTGATCCACCGTTTTACTC | 60 | 963 | 1 |

| R CGAACGAAAGCATGAAACAA | ||||

| selC tRNA | F GAGCGAATATTCCGATATCTGGTT | 60 | 527 | 45 |

| R CCTGCAAATAAACACGGCGCAT | ||||

| phcU tRNA | F TTC AGA AAA TCT CAT CAG TCG C | 60 | 475 | This study |

| R CAG AAA CAC AGA AAA GAA GCG A | ||||

| thrW tRNA | F TGT TTA CGT TAA CGC CTC TAC G | 60 | 586 | This study |

| R TGA GCT AAT TTG TTC GAG CTT T | ||||

| leuX tRNA | F TGC TGA AAA TTT CAG CAC TTA G | 55 | 520 | This study |

| R ATT TTT TGC TTT CCC TCA TAA C | ||||

| metV tRNA | F GGT AAA AAA AAG GTT GCA TGA A | 55 | 628 | This study |

| R TAA AAA TCA AGTTGA ACA GGC C | ||||

| afaE-8 and pheV | F GATTCACAACTACGCAGGGG | 65 | 1,800 | 38 |

| R ATTTGATTGACGAGACGAGGCGAA | ||||

| afaE-8 and pheU | F GATTCACAACTACGCAGGGG | 65 | 1,850 | 38 |

| R CCGAACTCAACCAGATTCTCCCC |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Bacterial DNA was released by the boiling method. PCR assays were carried out with the reagents and by the protocols supplied by the manufacturer (Pharmacia). The total reaction mixture volume was 50 μl, which contained 10 μl of supernatant from the boiled bacteria, the appropriate oligonucleotide primers at concentrations of 0.5 μM each, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Pharmacia), and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Pharmacia). The reactions with all the reaction mixtures included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and a final cycle of primer extension at 72°C for 7 min. The thermocycler reaction conditions for each primer pair were calculated on the basis of the annealing temperature and the length of the product size. PCR-amplified DNA was analyzed on 0.8 to 1% agarose gels by electrophoresis.

The phylogenetic group to which the E. coli strains belonged was determined by a PCR-based method, as described by Clermont et al. (13). Briefly, a two-step triplex PCR was performed directly with 3 μl of each of the bacterial lysates. The primer pairs used were ChuA.1-ChuA.2, YjaA.1-YjaA.2, and TspE4C2.1-TspE4C2.2 (Table 1). The PCR steps were as follows: denaturation for 4 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 5 s at 94°C, 10 s at 59°C, and 30s at 72°C; and a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. The data from the three amplifications resulted in assignment of the strains to phylogenetic groups as follows: chuA positive and yjaA positive, group B2; chuA positive and yjaA negative, group D; chuA negative and TspE4.C2 positive, group B1; chuA negative and TspE4.C2 negative, group A (13).

DNA probes specific for pheU tRNA, thrW tRNA, selC tRNA, leuX tRNA, metV tRNA, afaE-8, fimA, papC, sfaDE, f17c-A, iucD, irp2, fyuA, traT, iss, cvaC, hlyC, ehlyA, cnf, cdt3, and cdt4 were generated by PCR with suitable primer pairs (Table 1). Following amplification, the PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel. Appropriate fragments were cut from the gel, concentrated by ethanol precipitation, and/or purified with the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Inc. Chatsworth, Calif.) and then radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a random priming kit for labeling of oligonucleotides (Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology Inc., Baie d'Urfé, Québec, Canada), according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Detection of FyuA by immunoblotting.

The positive control bacterial strain used for PCR amplification of fyuA and for detection of the FyuA protein was Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32637 (kindly provided by Elisabeth Carniel). For this purpose, bacteria were grown overnight in LB broth with shaking at 28°C (Yersinia) or 37°C (E. coli) (54). Iron-restricted medium was prepared by the addition of 2,2′-dipyridyl to a final concentration of 50 μM, and iron-rich medium was prepared by adding 150 μM FeCl3. The same quantity of bacteria of each strain was sonicated, the cell debris was removed, and the supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The pellet fraction was incubated for 1 h in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at room temperature and centrifuged again (at 20,000 × g for 1 h). The supernatant was dialyzed against water and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in a 12% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and FyuA was detected with anti-FyuA antiserum kindly provided by J. Heesemann. Goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody, and the reaction was developed with hydrogen peroxide and 4-chloro-1-naphthol as the substrate.

PFGE and Southern hybridization.

The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Southern hybridization procedure used was a modified method of Gautom (21). The bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in LB broth and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The cells were washed in SE (75 mM NaCl, 25 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]) and centrifuged, and the optical density of the cells at a wavelength of 600 nm was adjusted to between 1.60 and 1.80 in cold TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). For each bacterial strain, 500 μl of suspension was added to 500 μl of prewarmed (60°C) 1.5% low-melting-point agarose (Sigma), and the mixture was immediately poured into a block former (plug mold). After solidification, the plugs were incubated overnight at 50°C in 1 ml of lysis buffer (1% [wt/vol] N-laurylsarcosine, 0.5 M EDTA [pH 9.5]) supplemented with 1 mg of proteinase K per ml. To inactivate the proteinase K, the plugs were then washed three times (each time 1 h) in TE buffer supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at room temperature and were run for 45 min at 60 V in 0.5× TBE buffer (44.5 mM Tris-borate, 12.5 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]). This premigration step removed degraded or extrachromosomal DNA from the gel and, thus, strongly reduced the smear background in PFGE (7). Macrorestriction of genomic DNA embedded in agarose blocks with restriction enzymes XbaI and SfiI was done as described by Birren and Lai (7). The DNA was separated on an AutoBase machine (Mandel Scientific Company Ltd.), which uses the principle of zero integrated field electrophoresis, a variation of the field inversion gel electrophoresis configuration, which gives sharper bands and minimum band inversion (7). PFGE was performed with a 0.8% agarose gel in 1× TBE buffer at room temperature without cooling or circulation of buffer. PFGE Marker I (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Laval, Quebec, Canada), a bacteriophage lambda DNA digest consisting of a ladder (20 bands) of increasing size from 48.5 kb (monomer) to approximately 1,000 kb (20-mer), was included as a DNA size standard. The digested genomic DNA separated in agarose gels was transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Immobilon-Ny+; Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer and hybridized under stringent conditions as described by Sambrook et al. (51).

Determination of plasmid profiles by nuclease S1 treatment and PFGE.

To determine the molecular sizes of the bacterial high-molecular-weight plasmids accurately, plasmid profiles were determined by using nuclease S1 treatment followed by PFGE, as described elsewhere (3). Half of each plug was rinsed with 200 μl of 1× nuclease S1 buffer (50 mM NaCl, 30 mM sodium acetate [pH 4.5], 5 mM ZnSO4) at room temperature for 20 min before being incubated with 1 U of Aspergillus oryzae nuclease S1 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) in 200 μl of 1× nuclease S1 buffer at 37°C for 45 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 μl of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). Electrophoresis was performed on a CHEF DR II PFGE apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) in 0.5× TBE buffer at 14°C. The gels were then run at pulse ramp times ranging from 2 to 35 s for 20 h at a constant voltage of 200 V. For size determination, a 48.5-kb bacteriophage lambda DNA ladder (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Laval, Quebec, Canada) was used as a molecular size marker. After electrophoresis, the gels were stained with ethidium bromide and were photographed with an AlphaImager 2000 camera (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.).

Experimental infections.

Strains were tested for pathogenicity by experimental infection of colostrum-deprived newborn piglets. When the piglets were 2 days old, they were intragastrically given 1 ml of an overnight culture in tryptic soy broth containing approximately 109 CFU of E. coli ml−1 diluted in 20 ml of 0.1% peptone water. The pigs were observed for clinical signs and were necropsied when moribund or at 4 days after inoculation if no clinical signs were observed. Bacteriological and pathological examinations were done as described previously (17, 18).

RESULTS

Virulence factor profiles including profiles for papG and papA alleles.

A total of 18 F165-positive septicemic E. coli strains from animals were originally selected from among a group of isolates found to be positive with probes for pap, sfa, or afa on colony hybridization. Only single copies of the pap-, sfa-, and afa-related sequences were found among these isolates (23, 41). These isolates had been divided into three groups on the basis of their adhesion phenotypes and genotypes. Isolates in group 1 were pap and sfa positive, isolates in group 2 were pap and afa positive, and isolates in group 3 were pap positive only (Table 2). Among 11 recognized variants of papA, the major pilin gene of E. coli P fimbriae, which are termed F7-1, F7-2, and F8 to F16 (36), only the F11 papA variant was detected in all 18 strains. The PapG adhesin occurs in three known molecular variants, encoded by alleles I to III of the corresponding papG gene (29). Allele III was detected in all strains in group 1, all of which belonged to serogroup O115, and in one strain in group 3, which belonged to serogroup O9. All of these strains were of porcine origin. Although the strains in groups 2 and 3 were positive for the pap operon, they were negative for all three of the papG alleles tested. All strains were positive for iucD, traT, and papC and were negative for cytotoxin genes commonly found in PAIs associated with ExPEC strains (cnf, hlyC). All strains were negative for afaE-3, afaE-7, nfaE, cdt3, cdt4, E-hlyA, ibeA or ibe10, kpsMT II, and tsh.

TABLE 2.

Virulence genotypes of 18 F165-positive E. coli strains isolated from swine and cattlea

| Strain | Group | Adhesins

|

Iron uptake

|

Serum resistance

|

Proteases

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| papC | sfaDE | afaE-8 | clpG | 20K | fimA | bmaE | iha | iucD | fyuA | irp1 | irp2 | iroN | kpsMT III | traT | iss | cvaC | ompT | espP | ||

| 5131 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| 4787 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 6389 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| 1776 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 393 | 1 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 2325 | 2 | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| 3292 | 2 | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 7867 | 2 | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 3863 | 2 | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

| 1401 | 2 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 3984 | 2 | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − |

| 215 | 2 | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| 2313 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| 2878 | 3 | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| 1195 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 1616 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| 3373 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 3719 | 3 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − |

The genotypes shown are for virulence factors detected by PCR and/or probe hybridization. + and −, presence and absence of a gene, respectively. papC, gene responsible for pilus assembly that is found in the central region of pap operon; sfal/focDE, genes found in the central region of sfa (S fimbriae) and foc (F1C fimbriae) operons; afaE-8, afimbrial adhesin gene, clpG, gene for structural subunit of CS31A surface antigen; 20K, F17C fimbria; fimA, gene for type 1 fimbrial major subunit; bmaE, gene for blood group M-specific adhesin; iha, IrgA (iron-regulated gene A of Vibrio cholerae) homologue adhesin; iucD, gene that encodes a membrane-bound enzyme synthesizing N6-hydroxylysine, the first product of the aerobactin biosynthesis pathway; iroN, gene for a novel catechole siderophore receptor; fyuA, gene for Yersinia siderophore receptor (ferric yersiniabactin uptake); irp1 and irp2, genes for iron-repressible high-molecular-weight proteins involved in the production of yersiniabactin; kpsMT allele III, gene for group III capsular polysaccharide synthesis (e.g., K3, K10, and K54); traT, gene for surface exclusion, serum survival (outer membrane protein); iss, gene for increased serum survival; cvaC, colicin V, located on conjugative plasmids (traT, iss, and antimicrobial resistance); ompT, gene for outer membrane protein T (protease); espP, gene for E. coli serine protease.

Strains in group 1 (pap and sfa positive) were also positive for fimA and iroN. Some strains were also positive for iss, cvaC, and ompT (Table 2). Strains in group 2 (pap and afa positive) harbored the chromosomal afaE-8 operon, which is specific for human and bovine septicemia and which seems to be very similar to the M agglutinin of uropathogenic strains from humans (38). Strains in group 2 possessed most of the virulence factors for which tests were conducted. They were all positive for bmaE, iucD, traT, and ompT. Three strains in this group (strains 2325, 1401, and 215) were positive for clpG, which encodes capsule-like antigen CS31A (4). Two strains (strains 3292 and 1401) were positive for the F17c (also known as 20K) fimbria. Four strains were positive for all the iron uptake systems for which tests were conducted. Four strains (strains 3292, 7867, 3863, and 3984) were positive for iss, and three strains (strains 3292, 7867, and 3863) were positive for cvaC (colicin V), which is carried by conjugative plasmids. Strain 215 was the only strain in group 2 that was positive for kpsMT III and negative for fimA. Although iucD and traT were found in strains in group 3 (pap positive), the presence of virulence genes was more variable. Strain 2878 was the only strain in this group that was positive for clpG. Interestingly, espP (E. coli serine protease), which is found in most enterohemorrhagic strains (9), was detected in three bovine F165-positive strains in groups 2 and 3 (Table 2).

Locations of PAIs encoding fimbrial operons.

Many of the PAIs identified are associated with tRNA loci (22). To study the regions containing the foo (pap-like), fot (sfa-related), and afaE-8 operons, DNA from PFGE separations was transferred to membranes and was hybridized with different tRNA gene-specific probes. For most strains (16 of 18 F165-positive strains), the band that hybridized with the probe for the foo operon cohybridized with the pheU tRNA gene-specific probe. This suggests that for these strains the insertion site of the putative PAIs encompassing the foo operon may be within the pheU locus. In two other strains the band that hybridized with the probe for the foo operon cohybridized with the selC tRNA gene-specific probe. This suggests that for these two strains, the insertion site of the PAIs encompasing the foo operon may be within the selC locus. To establish whether the virulence genes are linked in the same segment of the chromosome, suggesting their linkage in a PAI, the PFGE bands generated by digestion with two restriction enzymes (XbaI and SfiI) were hybridized with probes specific for papC, sfaDE, afaE-8, fimA, and F17c-A. None of these genes were located on a single restriction fragment, regardless of the restriction enzyme used, suggesting that either there are unknown virulence genes within these putative PAIs or they only contain fimbrial operons as a sole virulence factor.

Sets of PCR primers that could amplify the intact regions containing the tRNA genes were used to confirm that some fimbrial operons in F165-positive strains were inserted within or near tRNA loci (Table 1). We investigated whether the insertion sites of the fimbrial operons in the F165-positive isolates resided within the pheU, thrW, selC, leuX, and metV tRNA loci (data not shown). Our results indicated that, for most strains, the pheU locus was not amplified and that for two strains in group 3 the selC locus was not amplified. This suggests that in these isolates these tRNA loci were rearranged or disrupted. Different primer pairs covering the phenylalanine-specific tRNA genes (pheU and pheV) and the afa-8 gene were used to determine the insertion site of the afa-8 PAI (Table 1). In contrast to a recent study (38) on the afa-8 PAI, the insertion site of this afa-8 PAI in our group 2 strains was not detected in any of the phe tRNA loci.

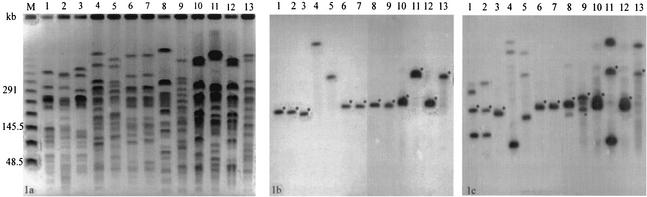

For 16 of 18 strains, the pheU tRNA gene-specific probe hybridized with the fragment that contained foo, which is similar to PAI IIJ96, which is also inserted next to the pheU locus, at 94 min of the E. coli K-12 chromosomal map (22) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the pheU tRNA gene-specific probe did not hybridize with the fragment containing the afa-8 operon. For only two group 2 strains (strains 2325 and 3292), the selC tRNA gene-specific probe hybridized with the fragment that contains the foo operon, which is similar to PAI I536 (22). Hybridization with foo (pap-like) and fot (sfa-related) gene-specific probes for strains in group 1 showed that these two operons are not physically linked. Although thrW tRNA was disrupted in all strains in group 1 that were positive for both foo and fot, the thrW tRNA gene-specific probe did not hybridize with the fragment containing the foo or fot operon. This is different from the finding for E. coli 536, in which an sfa operon homologous to fot was inserted next to thrW tRNA (PAI III536) (14). For the group 2 strains, hybridization with foo and afaE-8 gene-specific probes suggested that these two operons are not on the same fragment.

FIG. 1.

(a) Macrorestriction patterns of XbaI-digested genomic DNA from F165-positive strains analyzed by PFGE. (b and c) Southern blot of F165-positive strains digested with XbaI and separated by PFGE (b, hybridization with a pheU tRNA gene-specific probe; c, hybridization with a papC-specific probe). The asterisks on the right sides of certain fragments indicate the fragments that hybridized with both probes. Lanes: M, bacteriophage λ (PFGE ladder); 1, 5131; 2, 4787; 3, 1776; 4, 2325; 5, 3292; 6, 7867; 7, 3863; 8, 215; 9, 2878; 10, 1195; 11, 1616; 12, 3373; and 13, 3719.

The PFGE patterns, which were heterogeneous among the different strains, were similar within the particular groups. PFGE analysis demonstrated that the most closely related strains were within the same group but were also of the same origin.

Presence of HPI in F165-positive strains.

The HPI-specific genes (irp2, irp1, and fyuA) were found in 8 of 18 strains (only 7 of the 8 strains had all three genes); 5 of these strains belonged to group 2, and 3 of these strains belonged to group 3 (Table 2). Strain 1616 was positive for both irp2 and fyuA but was negative for irp1. In Yersinia spp. and E. coli, the site of HPI integration into the bacterial chromosome shares homology with the P4 bacteriophage attachment site and is located within an asn tRNA locus (10). To determine whether the HPIs of these strains were bordered by an asn tRNA gene locus, a set of primers whose sequences covered a portion of the int and asn genes was used (Table 1). The insertion site of the HPI in six of eight strains was next to the asnT tRNA gene, as demonstrated by PCR with primer pairs specific for asnT and int. In agreement with a recent report (1), the size of the PCR product was smaller than that in Y. pseudotuberculosis (1,100 bp instead of the expected 1,393 bp) in two strains (strains 2325 and 3292), suggesting that a deletion of approximately 300 bp had taken place in this region. Interestingly, in one strain (strain 1401), amplification by PCR produced a band of the expected size and two other smaller bands (1,200 and 1,100 bp). Two strains (strains 1195 and 1616) did not yield any amplification product with three different asn-specific primers (specific for asnT, asnV, and asnU) or the int-specific primer. All of these strains harboring HPIs were positive for IS100, as demonstrated by use of specific primers.

Certain E. coli strains (up to 3% of irp2-positive strains) carry a truncated fyuA-irp gene cluster, with deletions proceeding from fyuA or from both fyuA and irp1 to the 3′ end of the HPI. Such spontaneous deletions involve only the 3′ part of the fyuA-irp gene cluster and abrogate expression of the yersiniabactin receptor (54). In order to analyze the expression of fyuA in the eight strains carrying the Yersinia HPI, immunoblotting of outer membrane proteins was performed. One specific band of about 67 kDa for FyuA was detected in seven of the eight HPI-positive strains (data not shown).

Phylogenetic grouping results.

Phylogenetic analysis studies have suggested that E. coli is composed of four main phylogenetic groups (groups A, B1, B2, and D) and that virulent ExPEC strains mainly belong to groups B2 and D, whereas commensal strains belong to groups A and B1. Recently, Clermont et al. (13) described a simple and rapid phylogenetic grouping technique based on a triplex PCR. The results of the method, which uses a combination of two genes (chuA and yjaA) and an anonymous DNA fragment, showed a good correlation with those of reference methods (13). Examination of the strains by the triplex PCR method demonstrated that the strains in group 1, all of which were O115 and positive for foo and fot, belong to phylogenetic group B1, whereas all the strains in groups 2 and 3 belong to phylogenetic group A.

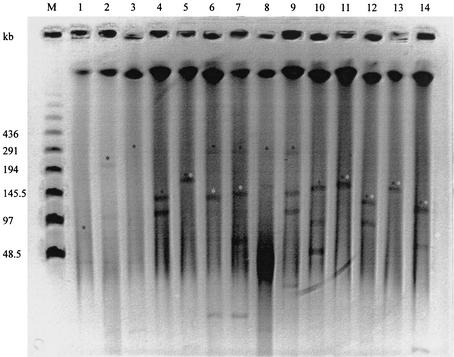

High-molecular-mass plasmid profiles.

In a previous study (24) it was shown that F165-positive strains carried several low-molecular-mass plasmids. In order to study the high-molecular-mass plasmids in 18 F165-positive strains, plasmid profiles were determined by using nuclease S1 treatment followed by PFGE. We identified plasmids with molecular masses ranging from 10 to 245 kb. Most of the strains that were positive by hybridization with probes specific for the iucD, traT, and iss genes harbored at least two high-molecular-mass plasmids of 90 to 245 kb. These plasmids were more frequently found in group 2 strains than in group 1 and 3 strains (Fig. 2.).

FIG. 2.

Plasmid profiles of 14 F165-positive isolates, determined by nuclease S1 treatment followed by PFGE analysis. Black asterisks, plasmid bands hybridizing with the traT-specific probe; white asterisks, plasmid bands hybridizing with the cvaC-specific probe. Lanes: M, bacteriophage λ (PFGE ladder); 1, 5131; 2, 4787; 3, 1776; 4, 2325; 5, 3292; 6, 7867; 7, 3863; 8, 1401; 9, 215; 10, 2878; 11, 1195; 12, 1616; 13, 3373; and 14, 3719.

Pathogenicities of strains in pigs.

The virulence of the F165-positive group 1 strains in piglets was high (Table 3). All O115 strains caused 100% mortality in pigs within 48 h of inoculation, with manifestation of gross lesions of polyserositis on necropsy. Pathogenicity was variable in strains of groups 2 and 3 (Table 3). Of four group 2 strains tested, three O11 or O9 strains caused 100% mortality in pigs within 48 h of inoculation, with manifestation of gross lesions of polyserositis on necropsy, whereas an O101 strain was nonpathogenic. Of three group 3 strains tested, an O9 strain caused mortality in pigs, whereas two O15 strains were nonpathogenic. All HPI-positive strains tested were pathogenic in piglets. On the other hand, the HPI-negative strains in group 1 tested were pathogenic, whereas those in groups 2 and 3 were less pathogenic or nonpathogenic in piglets. The strains in group 1 belong to phylogenetic group B1, whereas all strains in groups 2 and 3 belong to phylogenetic group A. No obvious relationship between the presence of the genes and pathogenicity in piglets was observed for any of the other virulence determinants.

TABLE 3.

Pathogenicities of F165-positive strains

| Group and strain | Source | Serogroup | No. of piglets inoculated | No. of piglets manifesting:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Macro lesionsa | Time of death after inoculation (h) | ||||

| Group 1 | ||||||

| 5131 | Porcine intestine | O115:K“V165” | 2 | 2 | 2 | 36-48 |

| 4787 | Porcine intestine | O115:K“V165” | 4 | 4 | 4 | 36-48 |

| 6389 | Porcine intestine | O115:K“V165” | 2 | 2 | 2 | 36-48 |

| 1776 | Porcine intestine | O115:K“V165” | 2 | 2 | 2 | 36-48 |

| 393 | Porcine intestine | O115:K“V165” | 2 | 2 | 2 | 40-48 |

| Group 2 | ||||||

| 2325 | Bovine extraintestine | O11:KF12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 48 |

| 3292 | Bovine intestine | O15,O35,O11 | NTb | NT | NT | NT |

| 7867 | Bovine intestine | O9:K28 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 48 |

| 3863 | Bovine intestine | O9:K28 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 1401 | Bovine intestine | O9:K28 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20-30 |

| 3984 | Porcine intestine | O101:K32 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 215 | Bovine intestine | O? | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Group 3 | ||||||

| 2313 | Bovine extraintestine | O15:KRVC383 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2878 | Bovine intestine | O15:KRVC383 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1195 | Porcine intestine | O9:K28 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 20 |

| 1616 | Bovine intestine | O9:K28 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 3373 | Porcine intestine | O9:K28 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 3719 | Porcine intestine | O9:K28 | NT | NT | NT | NT |

Macro lesions of polyserositis.

NT, not tested.

DISCUSSION

We have previously defined three phenotypic and genotypic groups among F165-positive animal E. coli strains on the basis of the expression of three different fimbrial operons. Strains in group 1 were positive for foo (pap-like) and fot (sfa-related) genes, and strains in group 2 or 3 were foo and afa positive and foo positive only, respectively (41). The results of this study suggest the presence of one or more PAIs (foo, fot, afaE-8, HPI) in septicemic strains isolated from animals. Moreover, the tRNA gene locus associated with some PAIs was also determined. The P-like operons were located near the pheU or selC tRNA gene and HPI sequences near the asnT tRNA gene. The insertion site of the HPI in six of eight strains was next to the asnT tRNA gene. The insertion site of afa-8 PAI in group II strains was not detected in any of the phe tRNA loci, which is in contrast to the findings in a recent study by Lalioui and Le Bouguenec (38) on the afa-8 PAI. The insertion site of fot, which belongs to the Sfa/F1C family was not next to thrW tRNA, unlike the sfa operon in E. coli 536.

The linkage of the foo operon to the pheU tRNA gene in 16 strains and to the selC tRNA gene in 2 others, the low G+C content of this operon (41 to 43%, compared to a 50.8% content in this operon of E. coli K-12 [data not shown]), and its presence in pathogenic strains indicates that this operon is part of a PAI. Moreover, the F1651 major fimbrial subunit (encoded by the foo operon) is closely related to that of P fimbria serotype F11 but bears a class III G adhesin similar to the Prs adhesin of F13 fimbriae (40) and may represent a new member of the family of P fimbriae. Although all F165-positive strains possessed papC, only six, all being of porcine origin, had a PCR-detectable papG allele corresponding to papG allele III. The fact that most porcine strains were positive for allele III whereas all bovine strains were negative for all three known alleles could suggest that there are unknown papG alleles among these isolates. The observed predominance of papG allele III among the porcine isolates (six of nine) in the present study is consistent with the previously demonstrated predominance of papG allele III in canine fecal E. coli isolates (35). The papG allele III is also the most prevalent papG allele among E. coli isolates from humans with cystitis and in some reports is prevalent among isolates from patients with bacteremia and pyelonephritis (29, 31). Among the 11 PapA variants tested, only the F11 papA allele was detected in all 18 strains. In addition to the F165 fimbria, which was detected in the strains tested in this study, which were isolated from pigs and calves with septicemia, interestingly, F11 is the predominant serotype of P fimbriae expressed by E. coli strains implicated in avian colisepticemia (16). This suggests that F11 fimbriae are frequently expressed by pathogenic E. coli strains isolated from animals with septicemia. Marklund and coworkers (43) have proposed that E. coli acquired the pap locus after the speciation of E. coli and have suggested that the different pap genes could have been acquired by horizontal gene transfer. Moreover, they proposed that the recent genetic exchanges involving the entire fimbrial gene clusters have occurred in response to selection pressures exerted by the host.

In addition to pap, the F165-positive strains contained multiple virulence-associated genes characteristic of ExPEC strains. These included sfa/focDE, afaE-8, F17c-A, clpG, bmaE, iucD, fyuA, traT, iss, ompT, and kpsMT III. Interestingly, no toxin genes commonly associated with ExPEC strains were present in these strains. The secreted proteases are virulence factors in many bacterial and nonbacterial pathogens. In our study, the EspP protease was found in three F165-positive strains. EspP is associated with enterohemorrhagic E. coli, induces cytopathic effects, has been shown to cleave coagulation factor V, and may thus promote intestinal hemorrhage (9). This is the first report on the presence of the espP gene in ExPEC strains. The absence of many genes that characterize ExPEC strains such as strains J96, 536, and CFT073 may indicate that in F165-positive strains these PAIs could potentially acquire additional virulence genes over time or that the virulence genes within these putative PAIs were deleted. Furthermore, these three strains are isolates from human infections, as opposed to animal infections, and are associated with different pathologies (e.g., strain J96 was from a patient with pyelonephritis). This could reflect a difference in selective pressure that results in this ExPEC strain with specific characteristics.

The majority of PAIs detected in enterobacteria are specific for particular species or even pathotypes. The HPI, first described in pathogenic Yersinia (10), has been detected in many enterobacterial species and pathotypes, including both enteroaggregative E. coli and ExPEC (54). In addition, more than 30% of E. coli isolates from the normal intestinal microflora also carry this island (54). The functional core of the HPI in Yersinia consists of 12 genes (irp1 to irp9, ybtA, fyuA, and intB). The mobility of the HPI elements may be associated with an intact integrase gene located at the left junction of the HPI. The fyuA, irp1, and irp2 genes were detected in all of the HPI-positive F165-positive strains. However, the yersiniabactin receptor FyuA was expressed in only seven of eight strains. The HPIs of F165-positive strains have features in common with the HPI elements of other enterobacteria, including pathogenic yersiniae. We showed that in six F165-positive E. coli strains, the HPI is inserted at the asnT tRNA gene. The asnT locus in Yersinia is linked to a gene whose sequence is highly homologous with that of a phage-derived integrase determinant termed intB. Furthermore, a copy of the IS100 insertion sequence present in the Yersinia pestis HPI (at the 5′ end) is also present in the HPIs of F165-positive E. coli strains. The HPI elements code for a particular iron uptake system, termed yersiniabactin. The question arises as to whether the HPI elements in E. coli indeed represent PAIs and whether they contribute to the survival of the strains in certain ecological niches. Most strains of the family Enterobacteriaceae carry genes that encode high-affinity iron uptake systems, such as the enterobactin and aerobactin systems. Thus, the reason for a third iron uptake system in E. coli, like that encoded by the HPI, remains to be clarified. It is conceivable that the bacteria use different iron uptake systems, depending on the environment or the stage of infection. However, siderophores not only are involved in providing the microorganisms with iron but also can affect the cellular immune system (e.g., by suppression of T-cell proliferation) (54). This dual role of siderophores may contribute to the pathogenicities of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and as a cause of extraintestinal infections. All HPI-positive F165 E. coli strains tested were pathogenic in piglets. Nevertheless, the HPI is not essential for some F165-positive strains, as shown by its absence from group 1 strains, which were pathogenic.

Four main phylogenetic groups (groups A, B1, B2, and D) were described by Herzer et al. (28) on the basis of examination of the 72 strains in the ECOR collection (46) by comparison of several genetic markers by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis. It may be relevant to these observations that isolates belonging to ECOR subgroup A have a significantly smaller genome than those belonging to either subgroup B2 or subgroup D, which have the largest genomes among natural isolates of E. coli (8). The E. coli genome varies from 4.5 to 5.5 Mb (49). For example, E. coli MG1655 has a genome of 4.63 Mb, and E. coli J96, which belongs to phylogenetic group B2, has a genome of 5.12 Mb (49). We determined the genome size of strain 4787, which belongs to phylogenetic group B1, by PFGE using three different restriction enzymes (SfiI, NotI, and XbaI) (data not shown). The genome of strain 4787 is estimated to be about 4.9 Mb, which is larger than that of E. coli K-12 but smaller than that of pathogenic strain J96.

Although F165-positive strains have been isolated from clinical cases and most of them are pathogenic in experimental infections, they fall into groups A and B1 of the phylogenetic scheme proposed by Herzer et al. (28). In a study by Picard et al. (48), commensal strains belonging to phylogenetic groups A and B1 were shown to be devoid of virulence determinants and did not kill mice. Some strains of phylogenetic groups A, B1, and D were able to kill the mice and possessed virulence determinants. Strains of the B2 phylogenetic group are highly virulent and possess the highest level of virulence determinants. Certain F165-positive strains possess virulence attributes such as P-like fimbriae, HPIs, O serotypes, and phylogenetic groups that can be associated with pathogenicity, as tested in our model. F165-positive strains in phylogenetic group A possessed more virulence factors than those in phylogenetic group B1, but the strains in group B1 were more virulent in piglets than the strains in group A. It is not known why strains in our group 1 (which belong to phylogenetic group B1) are more virulent in our experimental model, despite the presence of fewer virulence markers than the numbers of virulence markers in strains of the two other groups. It is possible that some virulence genes have not yet been discovered or that these strains may contain a new PAI(s), or their virulence could be related to the presence of “black holes,” genomic deletions that may enhance pathogenicity (44). The roles of the K“V165” O-antigen capsule and F1651 fimbriae in bacterial pathogenicity were examined by comparing the pathogenicities of mutants in experimental infections. The F1651 fimbriae and the K“V165” O-antigen capsule were strongly associated with bacterial survival in the extraintestinal organs and in the bloodstreams of infected piglets and with virulence. Fimbrial antigen F1651 promotes adherence of bacteria to porcine polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro but enhances resistance to phagocytosis. O-antigen capsule K“V165” is required for resistance to the bacterial effects of serum and for resistance to phagocytosis by porcine polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro (20). It is also possible that certain factors, such as O type (e.g., O115, O78) and K serotype (K1), are important in key steps for survival in the blood and resistance to bacterial killing by the host, i.e., bacterial killing in the presence of complement and phagocytes in extraintestinal tissues and fluids. A recent study suggests that extracellular polysaccharides as well as type 1 fimbrae are preeminent virulence determinants in uropathogenic E. coli strains in the murine urinary tract (2).

Thus, F165-positive strains that possess such key pathogenic traits but that lack certain virulence markers found in ExPEC strains would be relatively more pathogenic than commensal organisms but less pathogenic or pathogenic in fewer situations than the strains in phylogenetic group B2. Nevertheless, our study has shown that strains belonging to phylogenetic groups B1 and A (such as F165-positive strains) are not merely commensal but might be considered opportunistic pathogens. Comparison of the presence of virulence factors (Table 2), the ability of the strains to cause disease (pathogenicity) (Table 3), and the phylogenetic group suggest that the pathogenic origin of the strains in group 1 could be related to other virulence factors which are unidentified and/or could be related to host-dependent factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant (grant OGP0025120) to J.H. from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and grant 0214 from the Formation de Chercheurs et l'Aide à la Recherche.

We thank Charles Dozois (INRS, Institut Armand Frappier, Québec, Canada) for critical review of this article. Control strains and/or plasmids were kindly provided by James R. Johnson, Charles Dozois, Jorg Hacker, Gabriele Blum-Oehler, Ulrich Dobrindt, Harry L. T. Mobley, Thomas A. Russo, Lisa K. Nolan, Elisabeth Carniel, Juergen Heesemann, and Chantal LeBouguenec. Special thanks go to Hélène Bergeron, Céline Forget, and Ramin Behdjani for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach, S., A. de Almeida, and E. Carniel. 2000. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island is present in different members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., E. L. Buckles, C. V. Lockatell, J. R. Hebel, D. E. Johnson, C. M. Tang, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2002. Type 1 fimbriae and extracellular polysaccharides are preeminent uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence determinants in the murine urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1079-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton, B. M., G. P. Harding, and A. J. Zuccarelli. 1995. A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal. Biochem. 226:235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertin, Y., C. Martin, J. P. Girardeau, P. Pohl, and M. Contrepois. 1998. Association of genes encoding P fimbriae, CS31A antigen and EAST 1 toxin among CNF1-producing Escherichia coli strains from cattle with septicemia and diarrhea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:235-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingen, E., B. Picard, N. Brahimi, S. Mathy, P. Desjardins, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli strains causing neonatal meningitis suggests horizontal gene transfer from a predominant pool of highly virulent B2 group strains. J. Infect. Dis. 177:642-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binns, M. M., J. Mayden, and R. P. Levine. 1982. Further characterization of complement resistance conferred on Escherichia coli by the plasmid genes traT of R100 and iss of ColV, I-K94. Infect. Immun. 35:654-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birren, B. W., and E. H. C. Lai. 1993. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis: a practical guide. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 8.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1998. Chromosomal regions specific to pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli have a phylogenetically clustered distribution. J. Bacteriol. 180:1159-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunder, W., H. Schmidt, M. Frosch, and H. Karch. 1999. The large plasmids of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are highly variable genetic elements. Microbiology 145:1005-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carniel, E. 1999. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island. Int. Microbiol. 2:161-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherifi, A., M. Contrepois, B. Picard, P. Goullet, J. de Rycke, J. Fairbrother, and J. Barnouin. 1990. Factors and markers of virulence in Escherichia coli from human septicemia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 58:279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuba, P. J., M. A. Leon, A. Banerjee, and S. Palchaudhuri. 1989. Cloning and DNA sequence of plasmid determinant iss, coding for increased serum survival and surface exclusion, which has homology with lambda DNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 216:287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobrindt, U., G. Blum-Oehler, T. Hartsch, G. Gottschalk, E. Z. Ron, R. Funfstuck, and J. Hacker. 2001. S-fimbria-encoding determinant sfa (I) is located on pathogenicity island III (536) of uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain 536. Infect. Immun. 69:4248-4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dozois, C. M., M. Dho-Moulin, A. Bree, J. M. Fairbrother, C. Desautels, and R. Curtiss III. 2000. Relationship between the Tsh autotransporter and pathogenicity of avian Escherichia coli and localization and analysis of the Tsh genetic region. Infect. Immun. 68:4145-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dozois, C. M., J. Harel, and J. M. Fairbrother. 1996. P-fimbriae-producing septicaemic Escherichia coli from poultry possess fel-related gene clusters whereas pap-hybridizing P-fimbriae-negative strains have partial or divergent P fimbrial gene clusters. Microbiology 142:2759-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairbrother, J., J. Harel, C. Forget, C. Desautels, and J. Moore. 1993. Receptor binding specificity and pathogenicity of Escherichia coli F165-positive strains isolated from piglets and calves and possessing pap related sequences. Can. J. Vet. Res. 57:53-55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairbrother, J. M., A. Broes, M. Jacques, and S. Lariviere. 1989. Pathogenicity of Escherichia coli O115:K“V165”strains isolated from pigs with diarrhea. Am. J. Vet. Res. 50:1029-1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairbrother, J. M., S. Lariviere, and R. Lallier. 1986. New fimbrial antigen F165 from Escherichia coli serogroup O115 strains isolated from piglets with diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 51:10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairbrother, J. M., and M. Ngeleka. 1994. Extraintestinal Escherichia coli infections in pigs, p. 221-236. In C. L. Gyles (ed.), Escherichia coli in domestic animals and humans. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom.

- 21.Gautom, R. K. 1997. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2977-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker, J., and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:641-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harel, J., F. Daigle, S. Maiti, C. Desautels, A. Labigne, and J. M. Fairbrother. 1991. Occurrence of pap-, sfa-, and afa-related sequences among F 165-positive Escherichia coli from diseased animals: FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 66:177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harel, J., J. Fairbrother, C. Forget, C. Desautels, and J. Moore. 1993. Virulence factors associated with F165-positive Escherichia coli strains isolated from piglets and calves. Vet. Microbiol. 38:139-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harel, J., C. Forget, J. Saint-Amand, F. Daigle, D. Dubreuil, M. Jacques, and J. Fairbrother. 1992. Molecular cloning of a determinant coding for fimbrial antigen F165(1), a Prs-like fimbrial antigen from porcine septicaemic Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:1495-1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harel, J., M. Jacques, J. M. Fairbrother, M. Bosse, and C. Forget. 1995. Cloning of determinants encoding F165(2) fimbriae from porcine septicaemic Escherichia coli confirms their identity as F1C fimbriae. Microbiology 141:221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and J. B. Neilands. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of the iucD gene of the pColV-K30 aerobactin operon and topology of its product studied with phoA and lacZ gene fusions. J. Bacteriol. 170:56-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herzer, P. J., S. Inouye, M. Inouye, and T. S. Whittam. 1990. Phylogenetic distribution of branched RNA-linked multicopy single-stranded DNA among natural isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:6175-6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, J. R. 1998. papG alleles among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis: associations with other bacterial characteristics and host compromise. Infect. Immun. 66:4568-4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, J. R., and J. J. Brown. 1996. A novel multiply primed polymerase chain reaction assay for identification of variant papG genes encoding the Gal(alpha 1-4)Gal-binding PapG adhesins of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 173:920-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson, J. R., J. J. Brown, and J. N. Maslow. 1998. Clonal distribution of the three alleles of the Gal(alpha 1-4)Gal-specific adhesin gene papG among Escherichia coli strains from patients with bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 177:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson, J. R., T. T. O'Bryan, D. A. Low, G. Ling, P. Delavari, C. Fasching, T. A. Russo, U. Carlino, and A. L. Stell. 2000. Evidence of commonality between canine and human extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains that express papG allele III. Infect. Immun. 68:3327-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson, J. R., T. A. Russo, P. I. Tarr, U. Carlino, S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic associations of two novel putative virulence genes, iha and iroNE. coli, among Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 68:3040-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson, J. R., A. L. Stell, P. Delavari, A. C. Murray, M. Kuskowski, and W. Gaastra. 2001. Phylogenetic and pathotypic similarities between Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infections in dogs and extraintestinal infections in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 183:897-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson, J. R., A. L. Stell, F. Scheutz, T. T. O'Bryan, T. A. Russo, U. B. Carlino, C. Fasching, J. Kavle, L. Van Dijk, and W. Gaastra. 2000. Analysis of the F antigen-specific papA alleles of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli using a novel multiplex PCR-based assay. Infect. Immun. 68:1587-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karch, H., S. Schubert, D. Zhang, W. Zhang, H. Schmidt, T. Olschlager, and J. Hacker. 1999. A genomic island, termed high-pathogenicity island, is present in certain non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli clonal lineages. Infect. Immun. 67:5994-6001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lalioui, L., and C. Le Bouguenec. 2001. afa-8 gene cluster is carried by a pathogenicity island inserted into the tRNA (Phe) of human and bovine pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Infect. Immun. 69:937-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Bouguenec, C., M. Archambaud, and A. Labigne. 1992. Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1189-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maiti, S. N., L. DesGroseillers, J. M. Fairbrother, and J. Harel. 1994. Analysis of genes coding for the major and minor fimbrial subunits of the Prs-like fimbriae F165 (1) of porcine septicemic Escherichia coli strain 4787. Microb. Pathog. 16:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maiti, S. N., J. Harel, and J. M. Fairbrother. 1993. Structure and copy number analyses of pap-, sfa-, and afa-related gene clusters in F165-positive bovine and porcine Escherichia coli isolates. Infect. Immun. 61:2453-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marc, D., and M. Dho-Moulin. 1996. Analysis of the fim cluster of an avian O2 strain of Escherichia coli: serogroup-specific sites within fimA and nucleotide sequence of fimI. J. Med. Microbiol. 44:444-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marklund, B. I., J. M. Tennent, E. Garcia, A. Hamers, M. Baga, F. Lindberg, W. Gaastra, and S. Normark. 1992. Horizontal gene transfer of the Escherichia coli pap and prs pili operons as a mechanism for the development of tissue-specific adhesive properties. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2225-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maurelli, A. T., R. E. Fernandez, C. A. Bloch, C. K. Rode, and A. Fasano. 1998. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3943-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDaniel, T. K., K. G. Jarvis, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1664-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochman, H., and R. K. Selander. 1984. Standard reference strains of Escherichia coli from natural populations. J. Bacteriol. 157:690-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oswald, E., P. Pohl, E. Jacquemin, P. Lintermans, K. Van Muylem, A. D. O'Brien, and J. Mainil. 1994. Specific DNA probes to detect Escherichia coli strains producing cytotoxic necrotising factor type 1 or type 2. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:428-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picard, B., J. S. Garcia, S. Gouriou, P. Duriez, N. Brahimi, E. Bingen, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1999. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect. Immun. 67:546-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rode, C. K., L. J. Melkerson-Watson, A. T. Johnson, and C. A. Bloch. 1999. Type-specific contributions to chromosome size differences in Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:230-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Russo, T. A., and J. R. Johnson. 2000. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1753-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 52.Schmidt, H., L. Beutin, and H. Karch. 1995. Molecular analysis of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect. Immun. 63:1055-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt, H., C. Geitz, P. I. Tarr, M. Frosch, and H. Karch. 1999. Non-O157:H7 pathogenic Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: phenotypic and genetic profiling of virulence traits and evidence for clonality. J. Infect. Dis. 179:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schubert, S., A. Rakin, H. Karch, E. Carniel, and J. Heesemann. 1998. Prevalence of the “high-pathogenicity island” of Yersinia species among Escherichia coli strains that are pathogenic to humans. Infect. Immun. 66:480-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarr, P. I., S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., S. Jelacic, R. L. Habeeb, T. R. Ward, M. R. Baylor, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]