Abstract

Naïve T helper (Th) cells differentiate in response to antigen stimulation into either Th1 or Th2 effector cells, which are characterized by the secretion of different set of cytokines. Th2 differentiation, which is critical for allergic airway disease, is triggered by signals of the T-cell receptor (TCR) and the cytokines generated during polarization, particularly IL-4. We determine here the potential role of the signaling adapter p62 in T-cell polarization. We report using p62−/− mice and cells that p62 acts downstream TCR activation, and is important for Th2 polarization and asthma, playing a significant role in the control of the sustained activation of NF-κB and late synthesis of GATA3 and IL-4 by participating in the activation of the IKK complex.

Keywords: asthma, atypical PKC, NF-κB, sequestosome 1, Th2 differentiation

Introduction

The abnormal activation and/or differentiation of CD4+ T lymphocytes along the T helper 2 cell (Th2) lineage underlie the pathology of asthma and other allergic diseases (Luster and Tager, 2004). Naïve Th cells differentiate in response to antigen stimulation into either Th1 or Th2 effector cells, which secrete different sets of cytokines and perform also different regulatory functions in the immune system (Mosmann and Coffman, 1989; Shuai and Liu, 2003). Th1 cells mainly produce IFN-γ and IL-2, and play an essential role in cell-mediated immune responses against intracellular pathogens. On the other hand, Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13, and are important in the control of humoral immunity and allergy. Understanding the signaling pathways controlling Th2 differentiation is of paramount importance not only because it would lead to better therapies for asthma but also because it constitutes a paradigmatic model of cell differentiation in which a large number of signaling cascades have to crosstalk for an adequate control of the process (Paul and Seder, 1994). Th2 differentiation is modulated by signals emanating from the T-cell receptor (TCR) and the cytokines generated during polarization, particularly IL-4, which is added in the culture medium of CD4+ T cells induced to differentiate into the Th2 lineage in vitro (Ho and Glimcher, 2002; Murphy and Reiner, 2002). Therefore, IL-4 is important for induction and maintenance of differentiated Th2 cells. It shares with IL-13 interactions with the IL-4R chain and activates the transcription factor Stat6 through a Jak1/Jak3 signaling pathway (O'Shea et al, 2002). The crosstalk between signals generated by the TCR and IL-4 results in the physiological activation of T cells to induce and activate Th2-polarized T cells (Murphy and Reiner, 2002). Recently, we have found that the atypical PKC isoform PKCζ plays a critical role in Th2 differentiation and allergic airway inflammation, acting upstream Jak1 in the IL-4 signaling pathway (Martin et al, 2005). PKCζ and the other atypical PKC isofom PKCλ/ι harbor a PB1 domain at their N-terminal region, which interacts with other PB1 domain-containing proteins, such as p62 and Par-6, that act as scaffolds conferring specificity to the kinase's actions (Moscat and Diaz-Meco, 2002). Thus, the binding of the aPKCs with Par-6 serves to locate these enzymes in the polarity pathways, whereas the aPKC–p62 interaction is important for the sustained activation of NF-κB during osteoclast differentiation (Moscat and Diaz-Meco, 2002; Duran et al, 2004b). Since PKCζ is important during Th2 polarization and asthma, and because p62 is a scaffold of the aPKCs in several cells systems, we sought to determine here the potential role of p62 in these biological processes. We have found that, in marked contrast to the PKCζ−/− phenotype, the loss of p62 does not lead to an appreciable impairment of the IL-4 signaling pathway but plays an essential role downstream of TCR activation in the stimulation of the late and sustained NF-κB pathway, a required event for Th2 polarization and allergic airway inflammation.

Results

Role of p62 in the secretion of Th2 cytokines

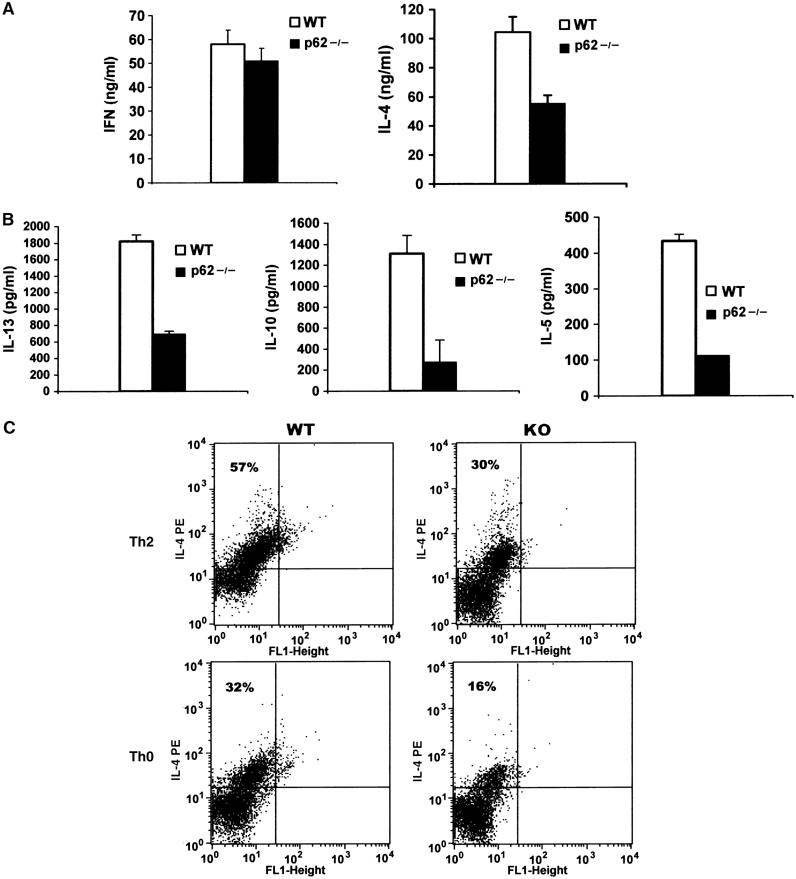

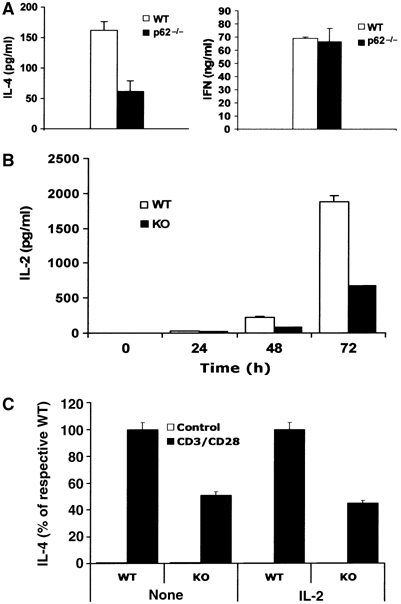

Since the loss of PKCζ results in impaired Th2 activation and asthma in mice, we reasoned that if p62 were the adapter of PKCζ in the IL-4 cascade, p62−/− mice should display defective Th2 polarization. To determine whether p62, like PKCζ, plays a role in lineage commitment of Th cells, CD4+ naïve T cells either wild-type (WT) or p62−/− were differentiated in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions, after which cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 antibodies for 24 h, and the secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 was determined in Th1 and Th2 cultures, respectively. Interestingly, whereas IFN-γ secretion is not affected (Figure 1A, left panel), IL-4 secretion is significantly reduced in p62−/− cells (Figure 1A, right panel). The synthesis of three other Th2 cytokines such as IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 was also inhibited in p62−/− Th2 cells (Figure 1B). The levels of intracellular IL-4 were determined in the presence of Brefeldin A by FACS analysis in CD4+ T cells induced to differentiate into the Th2 lineage for 5 days, and afterwards re-stimulated with anti-CD3 for 5 h. From these experiments, it is clear that the percentage of WT Th2 producing IL-4 is significantly more than that of p62−/− Th2 cells (Figure 1C, upper panels), consistent with the ELISA data of Figure 1A and B. Together, these results suggest that p62 plays a non-redundant role in Th2-polarized CD4+ T cells. Surprisingly, when naïve T cells were treated in parallel under Th0 conditions for 5 days and re-stimulated for 5 h as above, the levels of intracellular IL-4 were also reduced in the p62−/− cell cultures as compared with the WT controls (Figure 1C, lower panels). This suggests that p62 is required for optimal production of IL-4 by naïve T cells when stimulated through the TCR under non-skewing conditions. To further support these observations, we next determined whether the loss of p62 would affect the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-4 or IL-2 by naïve CD4+ T cells activated by anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28. From these experiments, it is clear that there is a significant impairment in the secretion of IL-4 and IL-2 but not of IFN-γ in p62−/− cells as compared to the WT controls (Figure 2A and B). These observations will be consistent with the notion that p62, although not absolutely required, is essential for the initial steps of the Th2 differentiation process. As IL-2 has been shown to be important for Th2 differentiation and IL-4 secretion (Cote-Sierra et al, 2004), we next determined whether the exogenous addition of IL-2 to the culture medium of naïve CD4+ T cells stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 would correct the defect in IL-4 secretion observed in the p62-deficient T cells. Results of Figure 2C show that this is not the case, as the same reduced secretion of IL-4 is observed in the absence and in the presence of exogenous IL-2. Of note, the reduced IL-2 levels produced by the activated naïve p62−/− T cells do not have an appreciable role in proliferation (Supplementary Figure 1A and 1B) nor in early or late apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 1C and 1D) of the mutant T cells. Collectively, these results suggest that p62 participate in the control of late-event TCR-mediated signaling pathways important for IL-4 production and Th2 polarization.

Figure 1.

Role of p62 in the secretion and synthesis of Th2 cytokines. Naïve CD4+ T cells either WT or p62−/− were induced to differentiate for 5 days along the Th1 (A, left panel) or the Th2 (A, right panel, and B) lineages as described under Materials and methods, after which they were restimulated for 24 h with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) and the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 was determined by ELISA. (C) IL-4 intracellular staining in the presence of Brefeldin A (BD GolgiPlug, added 4 h before harvest) of Th2 or Th0 WT and p62-deficient (KO) cells treated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) for 5 h. Inset numbers represent the percentage of IL-4-positive cells. The results in panels A and B are the mean±s.d. of three independent experiments with incubations in triplicate. The results in panel C are representative of another two experiments.

Figure 2.

Role of p62 in cytokine secretion of naïve T cells. Naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) for 72 h (A) or for different times (B), and secretion of IL-4 (A), IFN-γ (A) or IL-2 (B) was determined by ELISA. (C) Cells were stimulated as in panel A but in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-2 (10 ng/ml), and secretion of IL-4 was determined by ELISA. Results are the mean±s.d. of three independent experiments with incubations in triplicate.

Impaired Th2 signaling in p62-deficient T cells

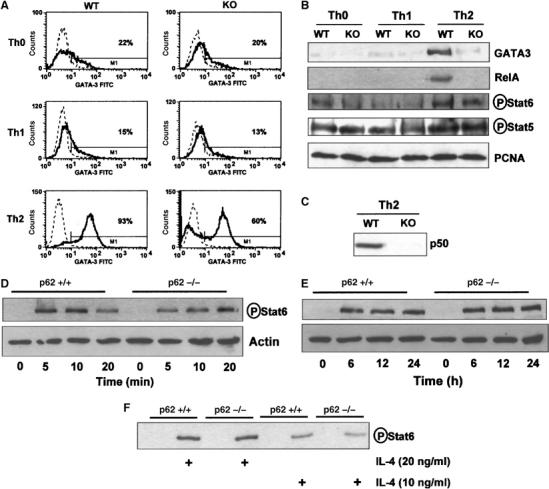

To gain insights into the biochemical alterations produced during the Th2 polarization process by the loss of p62, we initially determined the level of the transcription factor GATA3, a very well-established hallmark of Th2 differentiation (Ho and Glimcher, 2002). Thus, naïve CD4+ T cells were polarized under either Th0, Th1 or Th2 skewing conditions, after which intracellular GATA3 levels were determined by flow cytometry using the appropriate antibody as described previously (Martin et al, 2005). Data of Figure 3A show that GATA3 is synthesized in WT CD4+ T cells induced to polarize under Th2 but not under Th0 or Th1 conditions. Importantly, the loss of p62 significantly reduces the percentage of Th2 lymphocytes synthesizing GATA3 (Figure 3A). When extracts prepared from these cell cultures were analyzed by immunoblotting, it was apparent that GATA3 levels were reduced in the p62−/− Th2 cells as compared to the WT controls (Figure 3B). It is well established that, in addition to the activation of the TCR, IL-4 has to be added to these cell cultures for Th2 polarization to occur. The tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat6 is a reliable marker of the activation of the IL-4 signaling cascade. When phospho-Stat6 levels were analyzed in the above cultures, it was apparent that the absence of p62 only very modestly reduced Stat6 phosphorylation, as well as that the phospho-Stat5 levels, a marker of IL-2 signaling, were not affected by the loss of p62 (Figure 3B). Taken together, these results suggest that, in contrast to the PKCζ−/− phenotype in which Stat6 phosphorylation was severely impaired in Th2-polarized T cells (Martin et al, 2005), p62 does not appear to be critical for the Stat6 pathway. In fact when naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated with IL-4, the activation of Stat6 phosphorylation was not affected at all in the p62−/− cells (Figure 3D), again contrary to what has previously been observed in PKCζ−/− T cells (Martin et al, 2005). No differences in Stat6 phosphorylation were observed between WT and knockout (KO) cells even when stimulated with a lower dose of IL-4 (Figure 3D–F). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that p62 is important for optimal Th2 polarization but does not seem to be required for IL-4 signaling. In contrast, nuclear RelA (Figure 3B) as well as p50 (Figure 3C) levels were reduced in p62−/− Th2 cells as compared to the WT controls, indicating that p62 plays a significant role during NF-κB activation in Th2 differentiation. Interestingly, NF-κB has been shown to be essential for GATA3 synthesis (Das et al, 2001).

Figure 3.

Biochemical parameters of Th2 differentiation. (A) Intracellular staining of GATA3 in WT and p62−/− (KO) Th0, Th1 and Th2 cells differentiated for 5 days as described in Materials and methods. The solid line represents GATA3 staining; the dashed line corresponds to the mouse IgG1 isotype control. Inset numbers represent the percentage of GATA3-positive cells. (B) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear levels of GATA3, RelA, phospho-Stat6, phospho-Stat5 and PCNA in cell cultures of CD4+ T cells either WT and p62-deficient (KO) differentiated along the Th0, Th1 and Th2 pathways for 5 days as above; nuclear levels of p50 in Th2-polarized WT and p62−/− (KO) cells were determined by immunoblotting as in panel B. (C) Phospho-Stat6 levels of naïve CD4+ T cells stimulated with IL-4 (20 ng/ml) for different times (D, E) or with two concentrations of IL-4 for 20 min (F) were determined by immunoblotting. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Role of p62 in sustained NF-κB activation in T cells

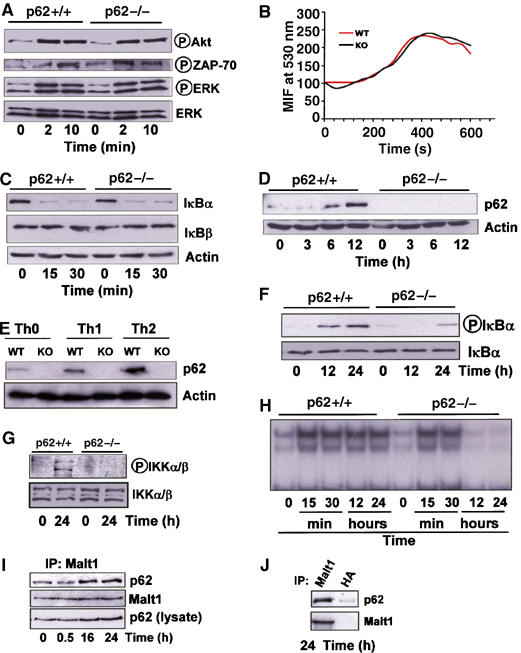

Th2 polarization is a long-term differentiation process that requires the sustained activation of TCR-derived signals. Since p62 has been shown previously in osteoclasts to play a critical role in the sustained, but not in the early, activation of NF-κB in that system (Duran et al, 2004b), we next determined here whether p62 was important for early and/or sustained T-cell activation. Thus, we first analyzed the impact that the loss of p62 has in early signaling events activated by the TCR. Our data demonstrate that the TCR proximal pathways such as the activation of Akt, ERK or ZAP-70 were not affected in p62−/− naïve CD4+ T cells triggered with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 (Figure 4A). Another marker of early T-cell activation is the intracellular Ca2+ level. Consistent with the lack of involvement of p62 in early T-cell signaling, intracellular Ca2+ levels increase similarly in WT and p62-deficient T cells activated with anti-CD3 (Figure 4B). Early NF-κB activation as determined by IκBα degradation was not inhibited in p62−/− T cells activated in response to anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28, whereas IκBβ degradation was not appreciably affected in either type of T cells (Figure 4C). These results indicate that p62 is not required for the activation of TCR-triggered early signaling events. Consistent with this, the phosphorylation of Bcl-10, which plays a critical role in the orchestration of the TCR-triggered signalosome complex (Huang and Wange, 2004), was not affected by the loss of p62 (not shown).

Figure 4.

TCR-activated signaling pathways. Naïve CD4+ T cells either WT or p62−/− were stimulated for different times with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) and the levels of different signaling molecules including p62 were determined by immunoblot analysis (A, C, D, F, G). Other cultures were differentiated for 5 days under Th0, Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions, as above, and the levels of p62 and actin were determined by immunoblotting (E). Naïve CD4+ T cells were loaded with Fluo-3 and stimulated with anti-CD3 (20 μg/ml) crosslinking. Histograms represent calcium mobilization analyzed by flow cytometry (B). Naïve CD4+ T cells activated as above with anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) for different times were analyzed by EMSA for NF-κB activation (H). Jurkat T cells were stimulated with PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (50 ng/ml) for different times, after which Malt1 was immunoprecipitated and the associated p62 was detected by immunoblotting (I); control immunoprecipitation of the 24-h stimulated samples with either anti-Malt1 antibody or an irrelevant anti-HA antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-p62 and anti-Malt1 antibodies demonstrate the specificity of the p62–Malt1 interaction (J). The results are representative of three independent experiments.

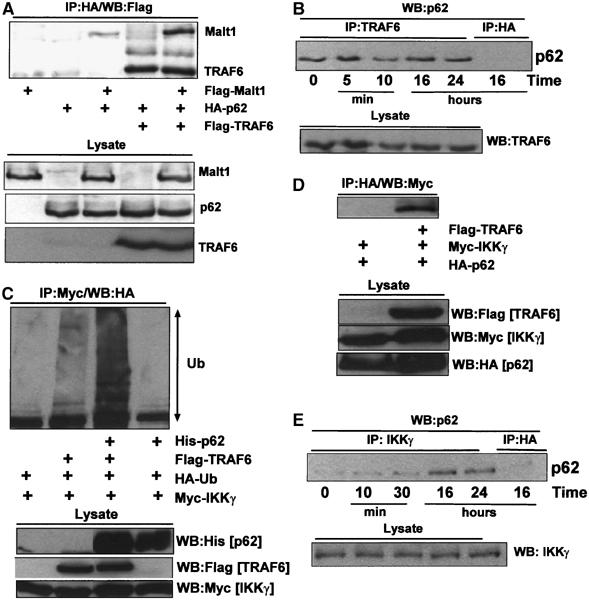

We have recently reported that p62 is induced during, and required for, late differentiation events in other cell systems (Duran et al, 2004b). In order to determine whether p62 is induced in Th cell differentiation, naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 and p62 levels were determined by immunoblotting at different times thereafter. Interestingly, p62 is dramatically induced in activated naïve T cells at 6 and 12 h post-stimulation (Figure 4D) and remained elevated up until 48 h, the maximum time measured (not shown). These results would be consistent with a model according to which p62 is induced in T cells committed to differentiate. The data of Figure 4E show that, even though p62 is detectably induced in T cells differentiating along the Th1 lineage, its synthesis is more potently activated in Th2-polarized T cells. These data, together with our results demonstrating that p62 is required for optimal Th2 differentiation and RelA activation in Th2-polarized cells (see above), suggest that p62 induction is a required event for late NF-κB signaling, GATA3 activation and subsequent T-cell polarization along the Th2 lineage. To further support this notion, naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 for 12 and 24 h, after which IκBα phosphorylation was determined by immunoblotting. Results of Figure 4F demonstrate that IκBα phosphorylation, a marker of NF-κB activity, was significantly inhibited in p62−/− T cells as compared to the WT controls. Consistently, phospho-IKK levels were robustly induced at 24 h post-activation of WT CD4+ naïve T cells but not in the p62-deficient ones (Figure 4G), indicating that p62 is required for late activation of IKK and NF-κB in naïve T cells. These results demonstrate that p62 is required for an optimal activation of NF-κB at later times in the differentiation process of CD4+ T cells, an event important for GATA3 induction and Th2 polarization. Results of Figure 4H confirm by EMSA the role of p62 in the sustained activation of NF-κB. The activation of NF-κB in T cells involves the formation of a signaling complex including three critical molecules, namely Carma1, Bcl-10 and Malt1 (Huang and Wange, 2004). Malt1 appears to be the most proximal to the IKK complex and its presence is absolutely required for the activation of NF-κB through a still not totally clarified mechanism (Ruefli-Brasse et al, 2003; Ruland et al, 2003; Sun et al, 2004; Zhou et al, 2004). In other cell systems in which p62 has been implicated in the activation of NF-κB, p62 has been shown to form part of the signaling complex that regulates IKK activation (Sanz et al, 2000; Duran et al, 2004b; Wooten et al, 2005). In order to determine whether this is also the case in T lymphocytes, we stimulated Jurkat T cells with PMA plus ionomycin for 30 min, or 16 and 24 h, after which Malt1 was immunoprecipitated and the potential association of p62 was determined by immunoblotting. Results of Figure 4I demonstrate that there is a basal association of p62 with Malt1 that is significantly induced at 16 and 24 h post-stimulation. However, at 30 min, the association of p62 with Malt1 did not differ from that seen in unstimulated cells (Figure 4I). Results of Figure 4J demonstrate that p62 co-immunoprecipitation with Malt1 is actually specific. These results are consistent with the concept that p62 is required for optimal activation of late but not early NF-κB and that p62 is directly or indirectly able to interact with Malt1. To better understand the details of this interaction, we first took into account that both p62 and Malt1 interact with TRAF6 (Sanz et al, 1999; Sun et al, 2004). Therefore, we transfected 293 cells with HA-p62 along with expression vectors for Flag-TRAF6 and Flag-Malt1 or empty plasmids. Afterwards, cell extracts were prepared, HA-p62 was immunoprecipitated and the associated Flag-TRAF6 and Flag-Malt1 was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody. The results of Figure 5A confirm our previous observations that TRAF6 potently interacts with p62. In addition, although Malt1 weakly interacts with p62 under these conditions, this interaction is potently enhanced in the presence of TRAF6 (Figure 5A). These results would be in keeping with the notion that Malt1 binds p62 and that TRAF6 helps in the formation of a p62/TRAF6/Malt1 complex. Next, we stimulated Jurkat cells with PMA plus ionomycin for different times, after which the association of endogenous p62 with endogenous TRAF6 was determined. From the data of Figure 5B it is apparent that p62 constitutively binds TRAF6 in unstimulated and in stimulated cells. Collectively, these results suggest that the preformed p62/TRAF6 complex is recruited to Malt1 during late T-cell activation. Recent results from different investigators showed that Malt1, likely through the ability of TRAF6 to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, controls IKK activation most likely by inducing its K63 ubiquitination (Ruefli-Brasse et al, 2003; Ruland et al, 2003; Sun et al, 2004; Zhou et al, 2004). These observations, together with our recent finding that p62 plays an important role in regulating TRAF6 ubiquitinating activity (Wooten et al, 2005), led us to determine whether p62 induces TRAF6 to promote the ubiquitination of the IKK regulatory subunit IKKγ (also known as Nemo). Thus, 293 cells were transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin and Myc-IKKγ either with or without His-p62 along with a plasmid control or Flag-TRAF6. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and the ubiquitination of IKKγ was determined by immunoblotting with anti-HA. Interestingly, the relatively weak ubiquitination of IKKγ promoted by TRAF6 is dramatically enhanced in p62-cotransfected cells, whereas p62 alone did not detectably induce IKKγ ubiquitination (Figure 5C). To further understand the mechanism whereby p62 controls IKKγ ubiquitination, 293 cells were transfected with HA-p62 and Myc-IKKγ along with a control plasmid or Flag-TRAF6. HA-tagged p62 was immunoprecipitated and the associated Myc-IKKγ was determined by immunoblotting with anti-Myc. The results of Figure 5D demonstrate that TRAF6 favors the interaction of IKKγ with p62. Interestingly, data of Figure 5E demonstrate that endogenous IKKγ recruits endogenous p62 at 16 and 24 h post-stimulation of Jurkat T cells but not at early times (10 and 30 min). Therefore, all these results will be consistent with a model according to which the formation of a Malt1–TRAF6/p62–IKKγ complex at late time after T-cell induction serves to trigger the ubiquitination of IKKγ and the activation of IKK and the NF-κB pathway.

Figure 5.

Important role of p62 in IKKγ ubiquitination. Extracts from 293 cells transfected with different combinations of HA-p62, Flag-TRAF6 and Flag-Malt1 expression plasmids were immunoprecipitated with anti HA antibody and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody (A). Jurkat T cells were stimulated for different times with PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (50 ng/ml), after which extracts were prepared and endogenous TRAF6 was immunoprecipitated and the associated endogenous p62 was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-p62 antibody; specificity control of the immunoprecipitation was carried out with an irrelevant anti-HA antibody (B). 293 cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin and Myc-IKKγ with or without combinations of His-p62 and Flag-TRAF6; extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and the ubiquitination of IKKγ was determined by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (C). 293 cells were transfected with HA-p62 and Myc-IKKγ along with a plasmid control or a Flag-TRAF6 expression vector, after which cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA and the associated IKKγ was detected by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody (D). Jurkat T cells were stimulated for different times with PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (50 ng/ml), after which extracts were prepared and endogenous IKKγ was immunoprecipitated and the associated endogenous p62 was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-p62 antibody; specificity control of the immunoprecipitation was carried out with an irrelevant anti-HA antibody (E). The results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Loss of p62 impairs allergic airway disease

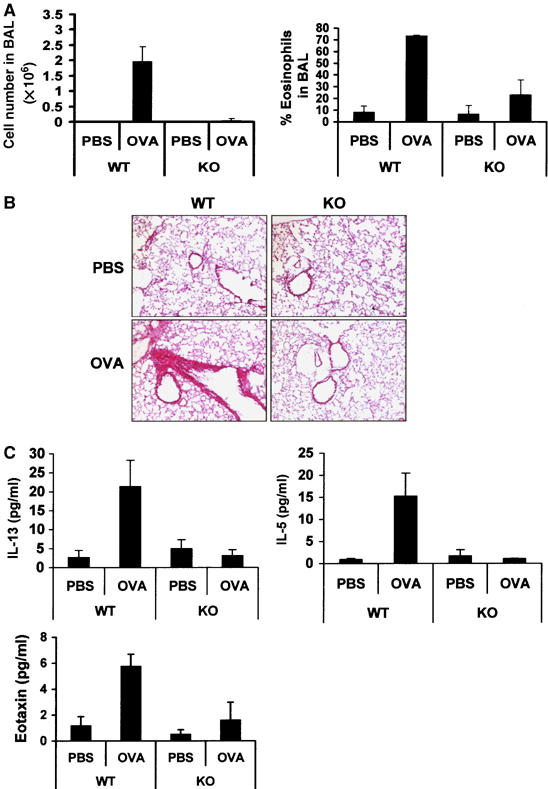

Since Th2 cells are important for allergic airway inflammation in a model of OVA-induced allergic airway disease, and p62 is required for optimal Th2 polarization, mice either WT or p62−/− were sensitized to OVA and then challenged twice with aerosolized antigen or PBS on the same day. Forty-eight hours after the aerosol challenge, mice were killed and the lungs were examined histologically by hematoxylin–eosin (C) staining for eosinophilic infiltration and bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) were performed to determine inflammatory cell recruitment. There was a robust increase in total BAL cell number in WT mice that were OVA-sensitized and challenged with aerosolized antigen as compared with PBS-challenged mice (Figure 6A, left panel), due especially to eosinophils (Figure 6A, right panel). However, these two parameters were reduced in p62−/− mice (Figure 6A), indicating that p62 is required for an optimal Th2-dependent inflammatory response. Consistent with this notion, HE histological analysis of lung sections from this experiment shows that whereas the challenged WT mice display major inflammation with massive perivascular and peribronchial infiltration with abundant eosinophils, p62−/− mice show a much more attenuated response (Figure 6B). In addition, IL-13, IL-5 and eotaxin levels in BAL (Figure 6C), which were dramatically increased in OVA-challenged WT mice, were severely reduced in similarly treated p62−/− mice. Collectively, these results demonstrate that p62 is necessary for asthma in vivo, and suggest that p62 is required for optimal Th2 differentiation and function.

Figure 6.

Role of p62 in OVA-induced allergic airway disease. Allergic airway inflammation was OVA induced in WT and p62−/− (KO), and total cell numbers and eosinophils in BAL fluids were determined (A). Lung sections were prepared and stained with H&E (B). Levels of IL-13, IL-5 and eotaxin were determined in BAL fluids by ELISA (C). Data shown are representative of two experiments that each time involved four mice of each genotype (B). Data in panels A and C are the mean±s.d. of each genotype by duplicate.

Discussion

Although the presence of IL-12 or IL-4 in the culture media of differentiating T lymphocytes is important for the polarization of these cells along the Th1 or the Th2 lineages, respectively, it is also clear that signals emanating from the TCR are critical for the commitment of these cells along each polarization program (Murphy and Reiner, 2002). Recently, several signaling molecules have been shown to play important roles during Th2 differentiation. These include, for example, SLAM, SAP and SLAT (Fields and Flavell, 2001; Wu et al, 2001; Tanaka et al, 2003; Cannons et al, 2004). Experiments in which SLAT was ectopically expressed demonstrate that it is able to drive Th2 polarization in vitro, which suggests that it may be important in this differentiation process (Tanaka et al, 2003). Consistent with this, SLAT is upregulated in Th2-polarized T cells but the kinetics of its induction indicates that SLAT does not appear to play a selective role in the initial TCR-derived signals required for Th2 polarization but probably in the TCR signals that serve to promote differentiation of already committed Th2 cells (Tanaka et al, 2003). In contrast, SAP does not appear to be induced during lymphocyte differentiation but its genetic ablation impairs Th2 polarization by inhibiting PKCθ recruitment and Bcl-10 phosphorylation, which leads to the impairment of NF-κB signaling without affecting ERK activation (Cannons et al, 2004). These results suggest that the inactivation of NF-κB is sufficient to block Th2 polarization, whereas ERK and the other activities are not sufficient to activate this process. Similar to SAP, p62 is required for NF-κB activation but only at late points in the T-cell differentiation program with no effects on early signaling cascades including Bcl-10 phosphorylation. This could be explained by the fact that, similar to SLAT, p62 is induced relatively late in the differentiation program of naïve T cells although it is more significantly accumulated when cells are polarized along the Th2 than the Th1 program. Therefore, p62 emerges as a novel critical component of the signaling complex controlling NF-κB stimulation and IL-4 synthesis at the level of GATA3 production in the late phases of T-cell activation, which are important for Th2 differentiation events and asthma. Although the precise mechanism whereby late TCR signals activate the sustained phase of NF-κB activation is not totally clear yet and might involve autocrine pathways, what is clear is that p62 is bound to Malt1 and is recruited to the IKK complex at late but not early times following TCR activation. This suggests that this p62-mediated late cascade may be proximal to TCR-triggered events. p62 is a scaffold protein that binds the aPKCs through its PB1 domain (Moscat and Diaz-Meco, 2002; Moscat et al, 2003). Interestingly, PKCζ is also important for Th2 differentiation and allergic airway inflammation (Martin et al, 2005); however, both molecules use different pathways to control that function—PKCζ is important for the activation of the IL-4/Jak1/Stat6 pathway (Duran et al, 2004a; Martin et al, 2005) and p62 is not but participates in NF-κB signaling. Although PKCζ has been demonstrated genetically to impinge in the NF-κB cascade in lung, embryo fibroblasts and B cells (Leitges et al, 2001; Martin et al, 2002; Duran et al, 2003), it is not essential for the activation of NF-κB in naïve (Martin et al, 2002) or Th2-polarized cells (Martin et al, 2005). This highlights the cell-type-specific functions of signaling molecules and demonstrates the importance of members of the atypical PKC pathways in the control of an appropriate immune response. Therefore, we can speculate that if an aPKC is responsible for the p62 actions on NF-κB in T cells, PKCλ/ι appears to be a good candidate. In this regard, it should be noted that the genetic inactivation of the aPKC inhibitor, Par-4, in mice leads to hyperactivation of T cells and increased generation of Th2 cytokines in ex vivo cultures of T cells (Garcia-Cao et al, 2003; Lafuente et al, 2003). Collectively, these results suggest that PKCλ/ι may be a critical component in the p62-mediated pathway to NF-κB activation during Th2 polarization. On the other hand, it has been demonstrated that Malt1 controls IKK activity through a process that involves the ubiquitination, in a K63 fashion, of the Nemo/IKKγ subunit of the IKK complex (Sun et al, 2004; Zhou et al, 2004). In addition, Nemo/IKKγ binds polyubiquitinated RIP1, which is an important intermediate in TNFα-activated NF-κB (Ea et al, 2006; Wu et al, 2006). However, how this novel function of Nemo/IKKγ impinges on the TCR pathway for IKK activation is not clear yet. Nonetheless, the data presented here demonstrate that Malt1, TRAF6, p62 and IKKγ form a complex that is important for the control of IKKγ ubiquitination, IKKα/β phosphorylation and NF-κB activation in Th2-polarized cells. Recent results implicate p62 in the control of ubiquitination during NF-κB activation. However, although important, IKKγ ubiquitination does not seem to be sufficient for triggering the NF-κB pathway, at least in T cells (Su et al, 2005). Whether PKCλ/ι somehow regulates this critical ubiquitination process or stimulates an additional signal for stimulation of the IKK complex is not clear yet and will be addressed as mice with tissue-specific genetic ablation of PKCλ/ι become available.

Materials and methods

Mice

The p62−/− mice were described previously (Duran et al, 2004b). Mice aged between 6 and 8 weeks were used for the in vitro experiments. Age- and sex-matched 10- to 12-week-old mice were used for the in vivo asthma model.

Antibodies, reagents and plasmids

Antibodies to murine CD3ɛ (145-2C11) and CD28 (37.51) and biotinylated CD8alpha (53-6.7), CD11b (Mac-1), CD16 (2.4G2), CD19 (1D3), CD24 (M1/69), CD62L (MEL-14), CD117 (2B8), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4-FITC (L3T4) and CD25-PE (PC61) were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Antibodies to Stat6 (S-20), phospho-ERK (E-4), ERK (K-23), GATA3 (HG3-31), Malt1 (C-16), RelA (C-20), ZAP-70 (LR), IκBβ (C-20), TRAF6 (H-274), Myc (A-14), HA (Y-11), His (H-15) and actin (I-19) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Stat5, Jak1, phospho-Stat6 (Tyr641), phospho-Stat5 (Y694), phospho-IKKα/β (Ser180/181), phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36) and anti-phospho-Tyr antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-IκBα antibody was from Calbiochem. Monoclonal anti-Flag(M2) was from Sigma. IL-2, IL-12, IL-4, as well as anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-5, anti-IL-4Rα and anti-IL-4 antibodies were from RD Systems (Minneapolis, MN). IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10 ELISA KITS were from Pharmingen and the IL-13 ELISA kit was from RD Systems. Specific polyclonal anti-p62 antibody was generated against the sequence encompassing amino acids 185–244 of p62. Monoclonal anti-human p62 was from Becton Dickinson. Expression plasmids for p62, TRAF6, IKKγ and UBI have been described previously (Sanz et al, 2000; Wooten et al, 2005). The Malt-1 plasmid (paracaspase) was a generous gift from Dr VM Dixit (Genentech Inc.).

CD4+ T-cell isolation and differentiation

To obtain naïve CD4+ T cells, single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens and mesenteric lymph nodes of the indicated mice and were incubated with biotinylated antibodies directed to CD8, CD16, CD19, CD24, CD117, MHC class II (I-Ab) and CD11b followed by anti-biotin-conjugated microbeads. Naïve CD4+ T cells were negatively selected in auto-MACS (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacture's instructions. Purified CD4+ T cells were labeled with antibodies specific for CD4, CD25 and CD62L and analyzed by flow cytometry to confirm the naïve status. Naïve CD4+ T cells (106 cells/ml) were differentiated to Th0 in the presence of irradiated APCs (106 cells/ml), immobilized anti-CD3 (1 μg/ml), IL-2 (10 ng/ml), anti-IFN-γ (4 μg/ml) and anti-IL-4 (4 μg/ml). For Th1 differentiation, IL-12 (4 ng/ml) and anti-IL-4 (4 μg/ml) were added to the culture, whereas IL-4 (4 ng/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (4 μg/ml) were added for Th2 differentiation. After 5 days, the cells were extensively washed, counted and restimulated as described.

Cytokine assays

Naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 72 h with CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus CD28 (2 μg/ml) and Th2-differentiated cells were restimulated for 24 h according to the experiments, after which supernatants were collected and cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA using commercially available kits. ELISA was also used to determine the levels of Th2 cytokines in BAL fluids.

Nuclear extract preparation and EMSA

Nuclear extract preparation from T cells and EMSA analysis were performed as described (Lafuente et al, 2003).

Calcium measurement

Single-cell suspensions of naïve T cells were loaded with Fluo-3 (Molecular Probes) during 30 min at 37°C. Calcium flux in response to anti-CD3 crosslinking with purified anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) followed by goat anti-IgG (10 μg/ml) was determined on a FACS-calibur flow cytometer.

OVA-induced allergic airway disease

p62−/− and WT mice (10- to 12-week-old) were immunized as described (Chensue et al, 2001). Briefly, on day 0, 15 μg of OVA (Sigma) in 200 μl of alum (Pierce) was injected i.p. to sensitize mice. On day 5, the animals received another i.p. injection of 15 μg of OVA in 200 μg of alum and, on day 12, mice were challenged with aerosolized 0.5% OVA in PBS (two challenges of 60 min each, 4 h apart). Control animals were aerosolized with PBS. On day 14, 40 h after the second OVA challenge, mice were killed for analysis. For histological analysis, lungs from PBS- or OVA-treated mice were inflated through the trachea with 50% Jung tissue freezing medium (Leika, Germany) in PBS. The right caudal lobe was trimmed, embedded, frozen and stored at −80°C. The appropriate institutional animal use and care committees approved all animal experiments.

Proliferation of T cells

Purified T cells were cultured at 1 × 105 cells/well in 160 ml of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ ml penicillin/streptomycin and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol and were stimulated with anti-CD3ɛ antibody (10 μg/ml) for 1 h in precoated plates and with soluble anti-CD28 mAb (1 μg/ml) for the indicated times. Proliferation was assessed by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine added (1 μCi/well) during the last 6 h of culture in triplicate wells. Cells were collected using a cell harvester and [3H]thymidine incorporation was quantified by scintillation counting (Wallac Oy 1450 Microbeta). The analysis of cell divisions of T cells was tracked following staining of cells with CFSE (Molecular Probes) and after 72 h of culture with or without CD3 (10 μg/ml) and CD28 (1 μg/ml). Analysis was performed on a FACS-calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with CELL-Questpro software.

Analysis of apoptosis

Analysis of apoptotic cells was determined by staining the cells for the binding of FITC-conjugated annexinV (Pharmingen) and propidium iodide after culture with or without CD3 (10 μg/ml) and CD28 (1 μg/ml). Analysis was performed on a FACS-calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with CELL-Questpro software. Viable cells were analyzed by excluding dead cells from the analysis on the basis of low forward-light scatter.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins was performed with whole-cell lysates of Jurkat T cells and cotransfection experiments in 293 cells. Cell extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol and protease inhibitor cocktail) and immunoprecipitations were performed with the ExactaCruz system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed on 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants SAF2003-02613 (to MTD-M) and SAF2005-0174 (to JM) from MCYT, Fundación La Caixa, and by an institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces to the CBMSO. PM is the recipient of Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas contract I3P-PC2003. JM is recipient of the Ayuda Investigación Juan March 2001.

References

- Cannons JL, Yu LJ, Hill B, Mijares LA, Dombroski D, Nichols KE, Antonellis A, Koretzky GA, Gardner K, Schwartzberg PL (2004) SAP regulates TH2 differentiation and PKC-[theta]-mediated activation of NF-[kappa]B1. Immunity 21: 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chensue SW, Lukacs NW, Yang TY, Shang X, Frait KA, Kunkel SL, Kung T, Wiekowski MT, Hedrick JA, Cook DN, Zingoni A, Narula SK, Zlotnik A, Barrat FJ, O'Garra A, Napolitano M, Lira SA (2001) Aberrant in vivo T helper type 2 cell response and impaired eosinophil recruitment in CC chemokine receptor 8 knockout mice. J Exp Med 193: 573–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote-Sierra J, Foucras G, Guo L, Chiodetti L, Young HA, Hu-Li J, Zhu J, Paul WE (2004) Interleukin 2 plays a central role in Th2 differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 3880–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Chen CH, Yang L, Cohn L, Ray P, Ray A (2001) A critical role for NF-kappa B in GATA3 expression and TH2 differentiation in allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol 2: 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2003) Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by zetaPKC in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. EMBO J 22: 3910–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran A, Rodriguez A, Martin P, Serrano M, Flores JM, Leitges M, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2004a) Crosstalk between PKCzeta and the IL4/Stat6 pathway during T-cell-mediated hepatitis. EMBO J 23: 4595–4605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran A, Serrano M, Leitges M, Flores JM, Picard S, Brown JP, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT (2004b) The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 is an important mediator of RANK-activated osteoclastogenesis. Dev Cell 6: 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ea CK, Deng L, Xia ZP, Pineda G, Chen ZJ (2006) Activation of IKK by TNFalpha requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol Cell 22: 245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields PE, Flavell RA (2001) Helper T cell differentiation: a role for SAP? Nat Immunol 2: 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cao I, Lafuente M, Criado L, Diaz-Meco M, Serrano M, Moscat J (2003) Genetic inactivation of Par4 results in hyperactivation of NF-kB and impairment of JNK and p38. EMBO Rep 4: 307–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho IC, Glimcher LH (2002) Transcription: tantalizing times for T cells. Cell 109 (Suppl): S109–S120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Wange RL (2004) T cell receptor signaling: beyond complex complexes. J Biol Chem 279: 28827–28830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente MJ, Martin P, Garcia-Cao I, Diaz-Meco MT, Serrano M, Moscat J (2003) Regulation of mature T lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation by Par-4. EMBO J 22: 4689–4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitges M, Sanz L, Martin P, Duran A, Braun U, Garcia JF, Camacho F, Diaz-Meco MT, Rennert PD, Moscat J (2001) Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-kappaB pathway. Mol Cell 8: 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster AD, Tager AM (2004) T-cell trafficking in asthma: lipid mediators grease the way. Nat Rev Immunol 4: 711–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Duran A, Minguet S, Gaspar ML, Diaz-Meco MT, Rennert P, Leitges M, Moscat J (2002) Role of zeta PKC in B-cell signaling and function. EMBO J 21: 4049–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Villares R, Rodriguez-Mascarenhas S, Zaballos A, Leitges M, Kovac J, Sizing I, Rennert P, Marquez G, Martinez AC, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2005) Control of T helper 2 cell function and allergic a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9866–9871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT (2002) The atypical PKC scaffold protein P62 is a novel target for anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer therapies. Adv Enzyme Regul 42: 173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Rennert P (2003) NF-kappaB activation by protein kinase C isoforms and B-cell function. EMBO Rep 4: 31–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann TR, Coffman RL (1989) TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol 7: 145–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KM, Reiner SL (2002) The lineage decisions of helper T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 933–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea JJ, Gadina M, Schreiber RD (2002) Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell 109 (Suppl): S121–S131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul WE, Seder RA (1994) Lymphocyte responses and cytokines. Cell 76: 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruefli-Brasse AA, French DM, Dixit VM (2003) Regulation of NF-{kappa}B-dependent lymphocyte activation and development by paracaspase. Science 302: 1581–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruland J, Duncan GS, Wakeham A, Mak TW (2003) Differential requirement for Malt1 in T and B cell antigen receptor signaling. Immunity 19: 749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz L, Diaz-Meco MT, Nakano H, Moscat J (2000) The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 channels NF-kappaB activation by the IL-1–TRAF6 pathway. EMBO J 19: 1576–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz L, Sanchez P, Lallena MJ, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (1999) The interaction of p62 with RIP links the atypical PKCs to NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J 18: 3044–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K, Liu B (2003) Regulation of JAK–STAT signalling in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 3: 900–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Bidere N, Zheng L, Cubre A, Sakai K, Dale J, Salmena L, Hakem R, Straus S, Lenardo M (2005) Requirement for caspase-8 in NF-kappaB activation by antigen receptor. Science 307: 1465–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Deng L, Ea CK, Xia ZP, Chen ZJ (2004) The TRAF6 ubiquitin ligase and TAK1 kinase mediate IKK activation by BCL10 and MALT1 in T lymphocytes. Mol Cell 14: 289–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Bi K, Kitamura R, Hong S, Altman Y, Matsumoto A, Tabata H, Lebedeva S, Bushway PJ, Altman A (2003) SWAP-70-like adapter of T cells, an adapter protein that regulates early TCR-initiated signaling in Th2 lineage cells. Immunity 18: 403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooten MW, Geetha T, Seibenhener ML, Babu JR, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J (2005) The p62 scaffold regulates nerve growth factor-induced NF-kappaB activation by influencing TRAF6 polyubiquitination. J Biol Chem 280: 35625–35629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Wang N, Gullo C, Howie D, Sosa MR, Edwards MJ, Borrow P, Satoskar AR, Sharpe AH, Biron CA, Terhorst C (2001) SAP controls T cell responses to virus and terminal differentiation of TH2 cells. Nat Immunol 2: 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CJ, Conze DB, Li T, Srinivasula SM, Ashwell JD (2006) NEMO is a sensor of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination and functions in NF-kappaB activation. Nat Cell Biol 8: 398–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Wertz I, O'Rourke K, Ultsch M, Seshagiri S, Eby M, Xiao W, Dixit VM (2004) Bcl10 activates the NF-kappaB pathway through ubiquitination of NEMO. Nature 427: 167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1