Abstract

Amphotericin B (AMB), micafungin, and caspofungin MICs, minimal fungicidal concentrations, and time-killing curves were determined in the presence and absence of 10% inactivated serum. AMB was the only agent with consistent killing activity (time required to achieve 99.9% of growth reduction was 2.1 to 3.2 h). The presence of serum enhanced caspofungin activity but lowered those of micafungin and AMB.

Candida guilliermondii is infrequently isolated from blood cultures (1 to 5%) (14), and infections caused by this species have been reported in cancer, surgical, and intensive care unit patients (13-14), including a pseudo-outbreak of candidemia in a neonatal intensive care unit (23). Malignancy, neutropenia, and bone marrow transplantation have been reported as risk factors for acquiring C. guilliermondii infections (22). Treatment of these infections may present problems, especially for immunocompromised patients; a high percentage of strains have diminished susceptibility to fluconazole (MIC at which 90% of organisms are inhibited, 16 mg/liter) and itraconazole (MIC at which 90% of organisms are inhibited, 1 mg/liter) (17-18). Amphotericin B (AMB), caspofungin, and micafungin have fungicidal activity against some Candida spp. (3-4, 8-9), but most studies have focused on Candida albicans and little is known about the killing activity of these agents against C. guilliermondii. A previous evaluation demonstrated that the same AMB MIC may correspond to different killing activities, depending on the Candida species or strain tested, and that each species has a different AMB killing pattern (5). Because the killing kinetics of AMB, caspofungin, and micafungin against C. guilliermondii are unknown, this study aimed to characterize the in vitro pharmacodynamics and fungicidal activities of these drugs against this species. Since these agents are highly protein bound (>90%) (9, 10, 11), the influence of serum on their in vitro activity has also been evaluated. For the first time, we provide the dynamics of the fungicidal activity of these three agents against C. guilliermondii.

Drugs.

AMB deoxycholate (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Madrid, Spain) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and caspofungin (Merck Sharpe & Dome, Madrid, Spain) and micafugin (Fujisawa Pharmaceutical Company, Japan) were dissolved in water. Further drug dilutions were prepared in standard RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) as recommended in the M27-A2 document (16).

MIC and MFC determination.

MICs were determined for 19 C. guilliermondii clinical isolates at least twice (on different days) in RPMI and RPMI plus 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich) by the M27-A2 method but using a higher inoculum (2.5 × 104 CFU/ml). Complement was inactivated by heating the undiluted serum (30 min, 60°C). Both MIC2 and MIC0 (≥50% and 100% growth reduction, respectively) were determined for caspofungin and micafungin and MIC0s for AMB. Minimal fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) were obtained by transferring 0.1 ml from all clear MIC wells (with or without serum) onto Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. The MFC was the lowest concentration that killed ≥99.9% of cells (<5 colonies) (4). Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and Candida krusei ATCC 6452 isolates were included as controls. AMB and caspofungin MICs for these two strains were within the accepted limits (2, 16).

Time-killing studies.

As previously described (5), tests were conducted for 8 of the 19 isolates (in duplicate on 2 separate days) with RPMI or RPMI plus 10% FBS inactivated, 105-CFU/ml inocula with 5-ml volumes and a 0.12-, 0.5-, 2-, 8-, or 32-mg/liter drug concentration. CFU were determined at 0, 2, 4, 6, 24, and 48 h. MICs and MFCs of the three agents were determined simultaneously, under the same testing conditions each time. Drugs were treated with the same heated serum each time a set of strains was tested in the presence or absence of serum. Furthermore, prepared microplates containing serum and drug were not stored before testing.

Data analysis.

For calculations of geometric mean MICs (GM-MICs) and GM-MFCs, off-scale MICs and MFCs were converted to the next highest values. Time-killing data were fitted to an exponential equation: Nt = N0 × e−Kt (Nt, viable cells at time t; N0, starting inoculum; K, killing rate; t, incubation time). The time to achieve 50, 90, 99, or 99.9% growth reduction at each concentration tested was calculated from the K value as described elsewhere (5).

Our echinocandin MICs (Table 1) were in agreement with those previously reported for this species (3, 8, 15, 19, 20), where the MIC2 was more reproducible than the MIC0. AMB was the most active agent, followed by micafungin and caspofungin (GM-MIC0 values, 0.1, 0.9, and 5.1 μg/ml, respectively). The antifungal activity in the presence of inactivated serum was isolate dependent, where AMB and micafungin lost activity (overall GM-MIC0 increases of 3.14 times for AMB and 3.88 times for micafungin); in contrast, caspofungin activity was slightly higher (overall 0.3-times-lower GM-MIC0) (Table 1). The lack of data regarding the effect of serum on the antifungal activities of these agents against C. guilliermondii precluded comparisons with our results. However, the effect has been antifungal agent dependent and controversial for C. albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Although micafungin MIC increases (three to seven dilutions, species dependent) were reported (9, 20) in the presence of either inactivated or noninactivated serum for C. albicans, the presence of serum did not affect AMB activity for this species in another study (24). Both no effect (C. albicans) and an increased activity (A. fumigatus) have been reported with caspofungin (3, 6). The reduction of the in vitro activities of AMB and micafungin against C. guilliermondii may be due to their high level of protein binding (>90%), while the increased activity of caspofungin in the presence of inactivated serum indicated that this increase was not due to complement mechanisms.

TABLE 1.

Activities of amphotericin B, caspofungin, and micafungin against 19 isolates of C. guilliermondiia

| Strain (no. of times tested) or parameter | Medium | Activity of drug

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphotericin B

|

Caspofungin

|

Micafungin

|

|||||||

| MIC0 | MFC | MIC2 | MIC0 | MFC | MIC2 | MIC0 | MFC | ||

| CJ-12 (4) | RPMI | 0.12-0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | 1-2 | 2->8 | >8 | 0.25-1 | 0.5-2 | 0.5-8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.12-1 | 0.25-1 | 0.5-1 | 2->8 | >8 | 0.5-4 | 2-8 | 4->8 | |

| CJ-19 (4) | RPMI | 0.12-0.5 | 0.12-0.5 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1->8 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.25-0.5 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25-1 | 0.5-1 | 0.06-0.5 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.12-1 | 1-4 | 2-4 | 2-4 | |

| CJ-21 (5) | RPMI | 0.016-0.06 | 0.03-0.5 | 1 | 1->8 | >8 | 0.12 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.25-1 |

| RPMI+S | 0.03-0.25 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.06-2 | 0.12->8 | >8 | 1-2 | 2-4 | 4-8 | |

| CJ-23 (5) | RPMI | 0.12-0.5 | 0.25-0.5 | 1-2 | 2->8 | 2->8 | 0.12-0.25 | 0.12-4 | 0.12->8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.06-1 | 0.25-2 | 0.03-2 | 0.25->8 | 0.5->8 | 1-4 | 1-8 | 1->8 | |

| CJ-24 (5) | RPMI | 0.03-0.12 | 0.06-0.12 | 1 | 1->8 | >8 | 0.12-0.25 | 0.12-2 | 0.25->8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.06-0.25 | 0.25-1 | 0.06-2 | 0.25->8 | >8 | 1-2 | 2-4 | 4->8 | |

| CJ-26 (3) | RPMI | 0.03-0.12 | 0.03-0.25 | 0.5-1 | >8 | >8 | 0.008-0.25 | 0.25-1 | 1-8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25-1 | 0.5-2 | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06-0.5 | >8 | 0.5-2 | 1-4 | 4->8 | |

| CJ-46 (3) | RPMI | 0.06-0.25 | 0.06-0.5 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 2->8 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5-1 | 1-4 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25-1 | 0.25-1 | 0.12-1 | 0.25-1 | 0.5-8 | 2-4 | 2-8 | 2-8 | |

| CY-115 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5-1 | >8 | >8 | 0.12-0.5 | 4->8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12-2 | >8 | >8 | 1-2 | 2->8 | >8 | |

| CY-116 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | 1 | 4 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | >8 | >8 | 2-4 | 4-8 | 8 | |

| CY-131 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | 4 | >8 | 0.06-0.25 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 |

| RPMI+S | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 4 | >8 | 0.5-2 | 2-8 | 8 | |

| CY-132 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | >8 | 0.12 | 0.25-0.5 | 1 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.5 | >8 | 2 | 2-4 | 8 | |

| CY-133 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5-1 | 1->8 | >8 | 0.12-0.25 | 0.5-2 | 1 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12-2 | 0.25->8 | >8 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |

| CY-134 (2) | RPMI | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12-0.25 | 0.5-1 | 1 | 0.008-0.06 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| RPMI+S | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12-0.25 | 0.12-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5-1 | 1-4 | >8 | |

| CY-135 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.12-1 | 8->8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25-1 | >8 | >8 | 2 | >8 | >8 | |

| CY-136 (2) | RPMI | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | 2->8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | 2->8 | >8 | |

| CY-137 (2) | RPMI | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | 1-2 | 4 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 2-4 | 4-8 | >8 | |

| CY-138 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | >8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5-1 | >8 | >8 | 2 | 4->8 | >8 | |

| CY-139 (2) | RPMI | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.25-0.5 | 4->8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | >8 | >8 | 2-4 | 4->8 | >8 | |

| CY-140 (2) | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.25-1 | 1->8 | >8 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03-0.06 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25-1 | 0.25-1 | >8 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| ATCC 6458 (3) | RPMI | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 0.06-0.12 | 0.06-0.12 | 0.12 |

| RPMI+S | 1 | 2 | 0.12-1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| ATCC 22019 (4) | RPMI | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1-2 | 2->8 | 2->8 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-1 | 0.5-1 |

| RPMI+S | 1 | 1-2 | 0.5-1 | 1-2 | 2->8 | 2-4 | 2-4 | 4-8 | |

| Overall range | RPMI | 0.016-0.5 | 0.03-0.5 | 0.12-2 | 0.5->8 | 1->8 | 0.008-1 | 0.03->8 | 0.03->8 |

| RPMI+S | 0.06-1 | 0.06-2 | 0.03-2 | 0.06->8 | 0.12->8 | 0.25-4 | 0.5->8 | 0.5->8 | |

| Overall MIC50 | RPMI | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1 | >8 | >8 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 |

| RPMI+S | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | >8 | 2 | 4 | 8 | |

| Overall MIC90 | RPMI | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | >8 | >8 | 0.5 | >8 | >8 |

| RPMI+S | 1 | 1 | 2 | >8 | >8 | 4 | >8 | >8 | |

| Overall GM | RPMI | 0.108 | 0.153 | 0.971 | 5.087 | 9.514 | 0.193 | 0.905 | 1.649 |

| RPMI+S | 0.34 | 0.499 | 0.434 | 1.727 | 5.652 | 1.587 | 3.512 | 6.579 | |

RPMI+S and RPMI, RPMI in the presence or absence of 10% inactivated FBS, respectively; MIC2 and MIC0, concentrations at which 50 and 100% of growth is inhibited, respectively; MIC50 and MIC90, concentrations at which 50% and 90% of organisms are inhibited, respectively; GM, geometric mean.

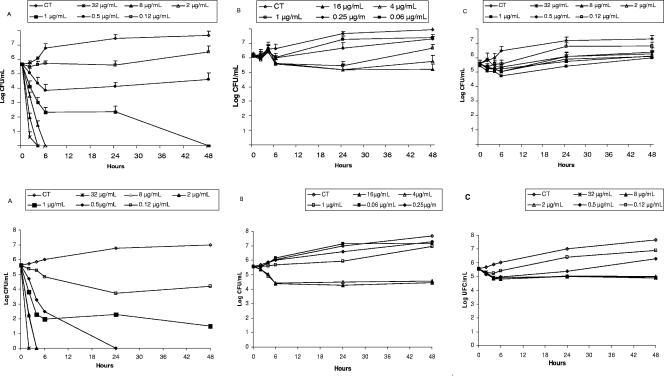

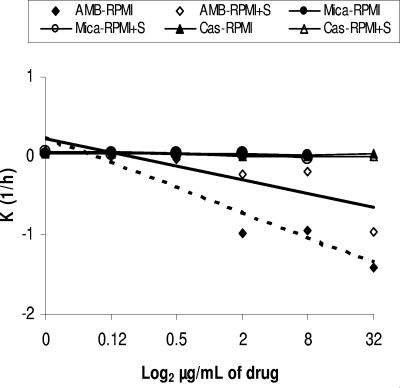

Figure 1 depicts the killing activity for C. guilliermondii (mean and standard deviation) in the presence or absence of serum. The killing activities of caspofungin and micafungin were not sustained because cell growth was seen at 24 h. In contrast, the killing kinetics of AMB was fast and increased with the drug concentration. The presence of serum diminished the killing activity of AMB (K value 1.8 times lower in presence of serum, respectively). The relationship between drug concentration and lethality was lineal (Fig. 2). The times required for 2 mg/liter of AMB to kill 50%, 90%, 99%, and 99.9% of the initial inoculum ranged from 12 to 19 min (t50 range) to 2.1 to 3.2 h (t99.9 range) (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Time-killing kinetics assays of AMB, micafungin, and caspofungin against C. guilliermondii. Average datum points and standard deviations are provided for eight C. guilliermondii isolates. Upper panels, RPMI medium. Lower panels, RPMI plus 10% inactivated FBS. A, amphotericin B; B, micafungin; C, caspofungin.

FIG. 2.

Relationship of amphotericin B, caspofungin, and micafungin concentrations and K values (regression lines) of survival time for C. guilliermondii in the presence (continuous line) or absence (dotted line) of inactivated fetal (10%) bovine serum. For caspofungin and micafungin, regression lines are practically horizontal (with and without serum) and almost identical (lines overlap).

TABLE 2.

Times to achieve 50, 90, 99, and 99.9% reductions in growth by amphotericin B for C. guilliermondii from the starting inoculum

| Parameter | Mean value (h) ± SD (range) at amphotericin B concn (μg/ml) of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 32 | |

| t50 | NRa | NR | 1.74 ± 2.17 (0.21-3.27) | 0.29 ± 0.05 (0.21-0.32) | 0.19 ± 0.05 (0.10-0.22) | 0.27 ± 0.25 (0.10-0.71) |

| t90 | NR | NR | 4.44 ± 7.21 (0.21-10.89) | 0.83 ± 0.16 (0.69-1.08) | 0.54 ± 0.16 (0.34-0.75) | 0.63 ± 0.44 (0.34-1.43) |

| t99 | NR | NR | 9.21 ± 14.41 (1.39-21.78) | 1.72 ± 0.32 (1.4-2.16) | 1.11 ± 0.33 (0.69-1.5) | 1.13 ± 0.61 (0.69-2.15) |

| t99.9 | NR | NR | 14.66 ± 21.62 (2.1-32.67) | 2.68 ± 0.48 (2.09-3.24) | 1.73 ± 0.49 (1.05-2.26) | 1.53 ± 0.60 (1.04-2.26) |

NR, not reached.

Killing patterns of these three antifungal agents have been reported for C. albicans, Candida glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and Candida tropicalis (3, 5, 9); we extended this knowledge for C. guilliermondii. The clinical response to AMB therapy for C. guilliermondii infections is controversial. Treatment failures have been documented in invasive or ocular infections (1, 7, 12, 21, 22), and they have been associated with either potential in vitro resistance (MICs of 1 to 4 mg/liter) or neutropenia. We did not detect in vitro resistance to AMB, since all isolates evaluated were killed by ≤2 μg/ml of AMB in less than 24 h (t99.9 = 2.68 ± 0.48 h) in the presence or absence of heated serum.

In summary, for the first time this study has provided the dynamics of the fungicidal activities of AMB, caspofungin, and micafungin against C. guilliermondii. AMB, caspofungin, and micafungin were active against C. guilliermondii, but only AMB showed fungicidal activity in the absence or presence of serum.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ainbinder, D. J., V. C. Parmley, T. H. Mader, and M. L. Nelson. 1998. Infectious crystalline keratopathy caused by Candida guilliermondii. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 125:723-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry, A. L., M. A. Pfaller, S. D. Brown, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, C. Knapp, R. P. Rennie, J. H. Rex, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2000. Quality control limits for broth microdilution susceptibility tests of ten antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3457-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartizal, K., C. J. Gill, G. K. Abruzzo, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, P. M. Scott, J. G. Smith, C. E. Leighton, A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and J. Balkovec. 1997. In vitro preclinical evaluation studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2326-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantón, E., J. Pemán, A. Viudes, G. Quindós, M. Gobernado, and A. Espinel-Ingroff. 2003. Minimum fungicidal concentrations of amphotericin B for bloodstream Candida species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 45:203-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantón, E., J. Pemán, M. Gobernado, A. Viudes, and A. Espinel-Ingroff. 2004. Patterns of AMB killing against seven Candida species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2477-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiller, T., K. Farrokhshad, E. Brummer, and D. A. Stevens. 2000. Influence of human sera on the in vitro activity of the echinocandin caspofungin (MK-0991) against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3302-3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dick, J. D., B. R. Rosengard, W. G. Merz, R. K. Stuart, G. M. Hutchins, and R. Saral. 1985. Fatal disseminated candidiasis due to amphotericin B-resistant Candida guilliermondii. Ann. Intern. Med. 102:67-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernst, E. J., E. E. Roling, C. R. Petzold, D. J. Keele, and M. E. Klepser. 2002. In vitro activity of micafungin (FK-463) against Candida spp.: microdilution, time-kill, and postantifungal-effect studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3846-3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinel-Ingroff, A. 1998. Comparison of in vitro activities of the new triazole SCH56592 and the echinocandins MK-0991 (L-743,872) and LY303366 against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and yeasts. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2950-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallis, H. A., R. H. Drew, and W. W. Pickard. 1990. Amphotericin B: 30 years of clinical experience. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:308-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajdu, R., R. Thompson, J. G. Sundelof, B. A. Pelak, F. A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and H. Kropp. 1997. Preliminary animal pharmacokinetics of the parenteral antifungal agent MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2339-2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacicova, G., J. Hanzen, M. Pisarcikova, D. Sejnova, J. Horn, R. Babela, I. Svetlansky, M. Lovaszova, M. Gogova, and V. Krcmery. 2001. Nosocomial fungemia due to amphotericin B-resistant Candida spp. in three pediatric patients after previous neurosurgery for brain tumors. J. Infect. Chemother. 7:45-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krcmery, V., S. Grausova, M. Mraz, E. Pichnova, and L. Jurga. 1999. Candida guilliermondii fungemia in cancer patients: report of three cases. J. Infect. Chemother. 5:58-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krcmery, V., and A. J. Barnes. 2002. Non-albicans Candida spp. causing fungaemia: pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. J. Hosp. Infect. 50:243-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller, F. M., O. Kurzai, J. Hacker, M. Frosch, and F. Muhlschlegel. 2001. Effect of the growth medium on the in vitro antifungal activity of micafungin (FK-463) against clinical isolates of Candida dubliniensis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:713-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast; approved standard, 2nd ed. NCCLS document M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 17.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and the International Fungal Surveillance Participant Group. 2003. In vitro activities of voriconazole, posaconazole, and four licensed systemic antifungal agents against Candida species infrequently isolated from blood. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:78-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, R. J. Hollis, and R. N. Jones. 2004. In vitro susceptibilities of rare Candida bloodstream isolates to ravuconazole and three comparative antifungal agents. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 48:101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero, M., E. Cantón, J. Pemán, and M. Gobernado. 2004. Estudio de la actividad in vitro de caspofungina sobre especies de levaduras diferentes de Candida albicans, determinada por dos métodos: M27-A2 y EUCAST. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 17:257-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tawara, S., F. Ikeda, K. Maki, Y. Morishita, K. Otomo, N. Teratani, T. Goto, M. Tomishima, H. Ohki, A. Yamada, K. Kawabata, H. Takasugi, K. Sakane, H. Tanaka, F. Matsumoto, and S. Kuwahara. 2000. In vitro activities of a new lipopeptide antifungal agent, FK463, against a variety of clinically important fungi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:57-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tietz, H. J., V. Czaika, and W. Sterry. 1999. Case report. Osteomyelitis caused by high resistant Candida guilliermondii. Mycoses 42:577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vazquez, J. A., T. Lundstrom, L. Dembry, P. Chandrasekar, D. Boikov, M. B. Parri, and M. J. Zervos. 1995. Invasive Candida guilliermondii infection: in vitro susceptibility studies and molecular analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 16:849-853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yagupsky, P., R. Dagan, M. Chipman, A. Goldschmied-Reouven, E. Zmora, and M. Karplus. 1991. Pseudooutbreak of Candida guilliermondii fungemia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:928-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhanel, G. G., D. G. Saunders, D. J. Hoban, and J. A. Karlowsky. 2001. Influence of human serum on antifungal pharmacodynamics with Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2018-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]