Abstract

Short nucleotide sequence repetitions in DNA can provide selective benefits and also can be a source of genetic instability arising from deletions guided by pairing between misaligned strands. These findings raise the question of how the frequency of deletion mutations is influenced by the length of sequence repetitions and by the distance between them. An experimental approach to this question was presented by the heat-sensitive phenotype conferred by pcaG1102, a 30-bp deletion in one of the structural genes for Acinetobacter baylyi protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, which is required for growth with quinate. The original pcaG1102 deletion appears to have been guided by pairing between slipped DNA strands from nearby repeated sequences in wild-type pcaG. Placement of an in-phase termination codon between the repeated sequences in pcaG prevents growth with quinate and permits selection of sequence-guided deletions that excise the codon and permit quinate to be used as a growth substrate at room temperature. Natural transformation facilitated introduction of 68 different variants of the wild-type repeat structure within pcaG into the A. baylyi chromosome, and the frequency of deletion between the repetitions was determined with a novel method, precision plating. The deletion frequency increases with repeat length, decreases with the distance between repeats, and requires a minimum amount of similarity to occur at measurable rates. Deletions occurred in a recA-deficient background. Their frequency was unaffected by deficiencies in mutS and was increased by inactivation of recG.

Short nucleotide sequence repetitions in DNA function significantly in biology. Their most likely source is “dislocation mutagenesis,” a process whereby one DNA strand serves as a template for perfecting partial sequence repetition by directing substitution of one or more nucleotides into the misaligned complementary strand (28, 29). Once established, such sequence repetitions can be increased by duplication or lost by deletion, with both genetic events being guided by hybridization between complementary components in the misaligned strands during replication (31). These events, apparently confined in proximity to 1 to 2 kb (the length of a typical gene) by the length of a replication fork, appear to be RecA independent (9, 31), in contrast to large sequence-guided mutations which depend upon RecA-mediated recombination.

The loss of nearby sequence repetitions through sequence-guided deletion between them can be envisioned as advantageous in eliminating DNA that no longer serves a useful function. In this view, dislocation mutagenesis perfects quasirepeats into repeats (28, 29), and replication through misaligned strands creates deletions (31) eliminating DNA that is not selected (1). Ironically, formation of sequence repetitions may help to stabilize newly evolving genes formed by duplication. Until sufficient nucleotide sequence divergence is achieved, RecA-mediated recombination is likely to create deletions whereby newly duplicated genes are lost. This creates a demand for rapid nucleotide substitution (23), and the demand could be met by multiple mutations introduced by dislocation mutagenesis as it creates separate patterns of short sequence repetition within newly duplicated genes. Such events may account for distinctive patterns of internal sequence repetition observed in homologous genes in which these repetitions presumably have been stabilized by conventional substitution of single base pairs (15, 19, 21, 23, 30, 35, 36, 44).

Some sequence repetitions must be conserved because they serve a clearly beneficial purpose. For example, they are found in origins of replication (6) and in operators that help to govern transcription. The interplay between contrasting forces, i.e., loss of DNA by sequence-guided deletion against maintenance of sequence repetition for useful function, was illustrated by genetic investigation of pcaO, the operator that governs transcription of the pca-qui operon in Acinetobacter baylyi strain ADP1. The operator contains three perfect 10-bp repeats, one palindromic and the other direct and separated by 10 bp. The repeats contribute to strong binding of the PcaU regulatory protein and thus are beneficial (41). The risk inherent in using sequence repetitions for this purpose is evident in the fact that selection for spontaneous mutants with impaired regulation of pca structural gene transcription frequently yielded strains that had undergone 20-bp deletions evidently guided by misalignment of the 10-bp direct repeats (13).

Contributions of short proximal sequence repetitions to gene loss, gain, and function beg questions about their stability. For example, if lengthy gene duplications are to be stabilized by acquisition of short internal sequence repetitions, the latter must be relatively if not completely stable. If short sequence repetitions can be beneficial, how long and how close can they be before there is significant risk of their loss through deletion? These questions have been addressed with several bacterial and phage systems (39, 40, 45), and the general conclusion is that the frequency of RecA-independent deletion increases sharply as the length of repeats increases and the distance between them decreases.

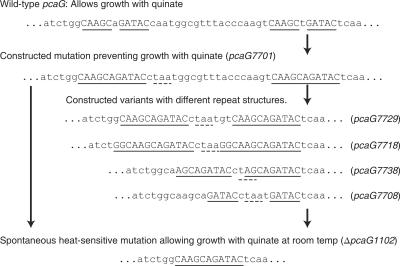

A different system for exploring RecA-independent deletion was presented by the phenotypic properties conferred by pcaG1102, a 30-base-pair deletion causing a temperature-sensitive phenotype allowing growth of A. baylyi strain ADP1 with quinate at 20°C but not at 37°C (14). The affected gene, pcaG, encodes protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, which initiates one of the central metabolic sequences in the β-ketoadipate pathway (24). As shown in Fig. 1, 10 of 11 nucleotides, repeated in the wild-type pcaG sequence, are likely to have guided the pcaG1102 deletion in the wild-type strain. This suggested that the influence of sequence repetition on deletion frequency could be explored by selecting mutants that acquired pcaG1102 by loss of DNA engineered so that it contained repetitions with varied lengths and distances of separation (Fig. 1). Advantages to this investigation were the ease with which A. baylyi can undergo manipulation by natural transformation (48), the background given by prior studies of spontaneous mutations in A. baylyi (14, 18, 47), and evidence suggesting that acquisition of sequence repetitions contributed to divergence of this chromosomal gene (22).

FIG. 1.

The direct repeat region within pcaG. Identification of the original spontaneous deletion mutation pcaG1102 led to the creation of variant repeat structures capable of undergoing deletion to generate the mutation.

To calculate mutation frequency, a direct assessment method called precision plating was developed in order to avoid the issues of indirect statistical methods based on mutant frequency, such as the method of the median and the fluctuation tests (34, 42). Mutants were constructed so that their pcaG genes contained variations in repeat sequences capable of producing a selectable phenotype following a specific deletion, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Deletion frequencies of the various mutations were determined and compared with repair frequencies of three different single-base mutations. The influence of recA, recG, and mutS knockout mutations on the frequency of sequence-guided deletion was assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid and strain construction.

Table 1 lists the strains and plasmids used in this study. Molecular biology manipulations were performed using standard manufacturer protocols. Cells of A. baylyi were made naturally competent by published methods (26). Crude lysates were prepared by the resuspension of pelleted cells from a 1.5-ml culture in 500 μl of lysis buffer (26), followed by incubation at 60°C for 1 h.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain(s) or plasmid(s) | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strain DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK−) phoA supE44 λ−thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| Acinetobacter baylyi strains | ||

| ADP1 | Naturally transformable isolate | 27 |

| ADP197 | recA100::Tn5 (Kmr) | 20 |

| ADP6146 | pcaH18; 1-bp insertion A504+A; ΔcatD101::Kmr | 18 |

| ADP6209 | ΔpcaH20; 1-bp deletion ΔΑ621; ΔcatD101::Kmr | 18 |

| ADP6407 | pcaH12; 1-bp substitution C304T; ΔcatD101::Kmr | 18 |

| ADP7021 | ΔmutS6::Ω(Str/Spr) | 47 |

| ADP7700 to ADP7768a | pcaG variants | This study |

| ADP7784 | pcaG7718 ΔrecG1::sacB-Kmr | This study |

| ADP7785 | pcaG7718 ΔrecG2; 1.8-kb deletion in recG Δ(G138-T1937) | This study |

| ADP7786 | pcaG7718 recA100::Tn5 (Kmr) | This study |

| ADP7787 | pcaG7718, ΔmutS6::Ω(Str/Spr) | This study |

| ADP7788 | pcaG7718; recG repaired | This study |

| ADP8534 | ΔpcaHG::sacB-Kmr; 1.0-kb deletion in pcaHG | A. Buchan |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-5Zf | Apr; cloning vector | Promega |

| pRMJ1 | Apr; sacB-Kmr cassette-bearing plasmid | 25 |

| pUC18 | Apr; cloning vector | NEB |

| pZR2 | Apr; 2.4-kb HindIII fragment containing pcaK′CHG in pUC18 | 18 |

| pZR7700 | pcaG7700; 1-bp insertion C237+T; nonsense mutation and frameshift in pcaG | This study |

| pZR7701 | pcaG7701; 1-bp insertion C237+T; 1-bp substitution T231A; template for all pcaG variants | This study |

| pZR7702 to pZR7768a | pZR7701-derived pcaG variants | This study |

| pZR7780 | ADP1 3.0-kb insert of recG into pGEM-5Zf | This study |

| pZR7781 | pZR7780 recG Δ(G138-T1937) | This study |

| pZR7782 | pZR7780 recG::BamHI (T1067G) | This study |

| pZR7783 | pZR7780 recGΔ::sacB-Kmr | This study |

pcaG variants are characterized by their repeat lengths and distances between homologous base pairs; more-detailed descriptions of their structures are given in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Introduction of variant sequence repetitions into pcaG.

The initial pcaG variants were derived from pZR2, a pUC18-derived plasmid containing pcaG and neighboring genes associated with protocatechuate metabolism (16, 46), using primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. pZR2 was modified using the Stratagene QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (37) with primers TSPG-BSU/D, generating pZR7700, which contains a frameshift and stop codon between the two imperfect wild-type repeats forming pcaG7700. pZR7700 was then modified with the QuikChange kit using primers TSPG-COU/D, introducing a silent T · A substitution making the repeats perfect and generating plasmid pZR7701, containing pcaG7701 (Fig. 1). Natural transformation with each plasmid followed by selection for replacement of the pcaG::sacB-Kmr cassette (25) in strain ADP8534 generated strains ADP7700 (pcaG7700) and ADP7701 (pcaG7701), respectively. The recombinant strains were selected at 22°C on LB plates containing 5% sucrose, and excision of the Kmr marker was confirmed by determining absence of growth on 10 mM succinate plates containing 15 μg ml−1 kanamycin (25). The recipient strain ADP8534, provided by Alison Buchan, was generated by insertion of the sacB-Kmr cassette from pRMJ1 (25) into the locus of a 1.0-kb deletion beginning at residue 90 of pcaH.

pZR7701 was used as a template for the creation of all other pcaG variants, except for a few which used other variants closer to their size to improve primer binding. A set of primers was chosen which corresponded to repeat lengths and repeat gaps of various sizes, designated LXX or IXX for a repeat or gap of length XX base pairs, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Inverse PCR (iPCR) (37) was performed using combinations of phosphorylated LXX and IXX primers and Pfu Turbo polymerase in a 50-μl reaction mixture; the reaction was verified on a gel. Half of that reaction mixture was removed and 1 μl of DpnI restriction enzyme added to digest parental template. A portion of that product was used in a 10-μl reaction mixture with high-concentration ligase for 30 min at 37°C. The resulting product was then transformed into DH5α as per the manufacturer's protocol and selected by demanding growth in the presence of 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin. Plasmids were purified and commercially sequenced with sequencing primer HG4 to verify their structures.

For nine of the variants the combinatorial approach was not suitable, and thus conventional two-primer site-directed mutagenesis was used (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). iPCR was performed on the template plasmid with the primer pairs and Taq polymerase under the same conditions as described above, and the product was digested with DpnI and transformed directly into DH5α, allowing the identical ends of the linear product to recombine in vivo and generate the desired result. DNA from plasmids containing the desired pcaG mutations was introduced into strain ADP8534, and recombinants in which the sacB-Kmr cassette had been replaced by the mutant pcaG DNA were selected at 22°C on LB plates containing 5% sucrose.

Introduction of knockout mutations.

Strain ADP7786 (recA::Kmr) was generated by transforming strain ADP7718 with lysate of strain ADP197 (20), followed by selection for growth on plates containing 10 mM succinate supplemented with 15 μg ml−1 kanamycin. Strain ADP7787 was generated by transformation of strain ADP7718 with lysate of strain ADP7021 (47) containing a mutS::Str/Spr mutation, followed by selection on 10 mM succinate plates containing 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 50 μg ml−1 spectinomycin.

The annotated genome sequence of A. baylyi (2) was used to design primers for cloning and mutagenesis of recG. RECG-OUTL/R primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify a 3.0-kb fragment containing recG, and the amplicon was cloned with the pGEM-T Vector System I kit from Promega. Escherichia coli DH5α cells that had acquired recombinant plasmids were selected with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), and clones containing plasmids with inserts were identified as white colonies. Restriction analysis of the plasmid from one of these colonies confirmed the presence of the insert containing recG, and the plasmid, pZR7780, was used as a template for Pfu Turbo iPCR with RECG-IN-U/D2 primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), followed by DpnI digestion of the template and blunt-end ligation of the product to create pZR7781. This plasmid contains ΔrecG2, a 1,800-bp deletion which is in translational frame within pcaG in order to minimize transcriptional disruption of comF, which is directly downstream.

In order to introduce ΔrecG2 into strain ADP7718, the sacB-Kmr cassette was inserted into recG. Site-directed mutagenesis with the RECG-BNF/R primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) was used with pZR7780 to create an internal BamHI site in recG, and the sacB-Kmr cassette from pRMJ1 was ligated into this site, forming pZR7783. This plasmid was linearized, and its recG::sacB-Kmr DNA was introduced into strain ADP7718 by natural transformation, followed by selection for kanamycin resistance. The resulting strain, ADP7784, was transformed with ΔrecG2 DNA from pZR7781, followed by selection for growth at room temperature in the presence of 5% sucrose. A recombinant colony, strain ADP7785, was shown by sequencing to have the ΔrecG2 mutation. To confirm the absence of secondary mutations that might have been acquired during the construction of ADP7785, wild-type recG was restored to this strain by selection of a recombinant that had acquired recG::sacB-Kmr from pZR7783 and restoration of wild-type recG in the recombinant with DNA from pZR7780.

Precision plating.

Each precision plate contained 10 ml of minimal medium (38) in 2% American Bioanalytical agar (bacteriological) supplemented with 3 mM quinate and 1 mM succinate. The relative chemical stability of quinate made it a preferred carbon source over protocatechuate. Plates were stored at 4°C.

Strains to be tested were cultured in minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM succinate overnight. These cultures were then diluted by 10−3, and 50-μl samples were spread on multiple precision plates and on single control plates with 3 mM quinate alone. Plates were incubated for 5 days at room temperature, at which time large colonies on the precision plates were counted and the background was verified for the presence of small nonmutant colonies and a characteristic brown tint, indicating that quinate had been metabolized to protocatechuate. Plates containing quinate alone were checked to confirm that ΔpcaG1102 mutants were not present in significant numbers in the inoculum.

Mutation frequency was calculated as the average number of large colonies per plate divided by the nonmutant background, which was estimated to be 108 cells per plate. This estimate was determined by measuring the CFU in 10 ml of a liquid culture containing 10 mM succinate. Multiple mutation events may occur independently per small colony, but under the precision plating method such colonies are few relative to those with single mutation events (1% or less). Thus, the calculated mutation frequency should slightly underestimate the true mutation frequency, it but does so well within other sources of uncertainty.

Large mutant colonies were sampled at random and shown to have a heat-sensitive phenotype such as would be conferred by ΔpcaG1102. The presence of the 30-bp deletion in this gene was confirmed by sequencing it from eight of the colonies.

RESULTS

Growth on precision plates.

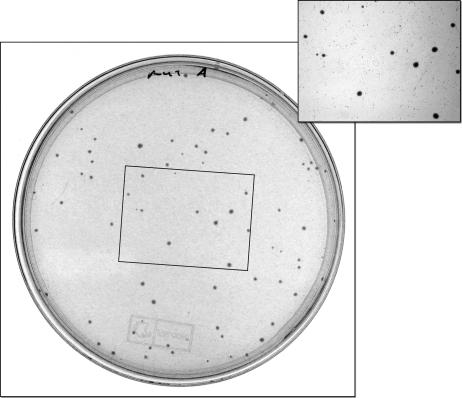

The protocol used in this study determined differences in the amounts of growth with two substrates, succinate and quinate (Fig. 2). After inoculation, thousands of nonmutant colonies growing nonselectively on succinate appeared, reaching their full but tiny size by 2 days. At this time, slightly larger colonies were observed. By 3 days, the larger colonies on the precision plates became more evident and a distinctive brown tint indicated metabolism of quinate into protocatechuate. At 4 days, the tint became stronger and the mutant colonies were clearly evident. At 5 days, they were all easily distinguishable from the nonmutant colonies in the background. No new mutant colonies appeared after 4 days. The overall pattern indicated that the succinate was almost totally consumed, and nonselective growth halted within the first 2 days, followed by a period of time in which mutants arising on the plate in the first phase continued to grow while nonmutants ceased growth. Occasionally, colonies appeared on plates containing quinate alone after 3 days of incubation. The presence of these colonies indicated that mutations had occurred in the inoculum, and therefore data from the corresponding precision plates were not recorded.

FIG. 2.

A sample precision plate. During the initial phase of growth, nonmutants rapidly grow to their maximum size, which is tiny. The small colonies are visible in the background of the inset. Mutations which restore function of PcaG allow growth with quinate and produce the large colonies visible in both pictures. The small colonies cease growth after 2 to 3 days; identifiable mutant colonies appear after 3 to 4 days and reach a readily distinguishable size by 5 to 6 days.

Evaluation of the precision plating method.

The first quantitative test of precision plating was to determine that it provided reproducible results. For these experiments, strain ADP7718 was used because it produced about 80 deletion mutant colonies per plate, allowing relatively high accuracy with few trials. As indicated in Table 2, there was some variation from experiment to experiment, but the number of mutant colonies did not vary greatly from the average value. Possible sources of the variation were explored, as summarized in Table 3. Doubling the inoculum size did not significantly vary the number of mutants that arose on precision plates, and only a slight increase in number was evident in plates containing twice the amount of quinate or twice the volume of medium. Doubling both the quinate amount and plate volume gave essentially the same results. Doubling the succinate amount led to somewhat less than the predicted twofold increase in mutant colonies, perhaps because these plates were crowded and other factors may have contributed to limitations in growth. To compensate for variation, it is therefore presumed that nonselective growth can vary by as much as 5%, and confidence limits have been determined by using the upper and lower values for this variation in the calculation of the corresponding Poisson confidence limits (11).

TABLE 2.

Reproducibility of precision plating

| Trial | No. of plates | No. of mutant colonies

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% confidence interval

|

|||

| Poisson | Adjusted | |||

| 1 | 6 | 75 | 68-82 | 64-86 |

| 2 | 6 | 94 | 87-102 | 82-107 |

| 3 | 4 | 76 | 67-85 | 64-89 |

| 4 | 9 | 79 | 74-85 | 70-89 |

| 5 | 8 | 83 | 77-90 | 73-94 |

| 6 | 4 | 88 | 79-98 | 75-103 |

| All | 37 | 82 | 79-85 | 75-89 |

TABLE 3.

Influence of plate conditions on precision plating

| Growth conditionsa | No. of mutant colonies

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% confidence interval | Ratio of test/normal | |

| Standard (10 μmol SUC, 30 μmol QUI, 10-ml plate) | 82 | 75-89 | 1 |

| Double succinate amt (20 μmol SUC, 30 μmol QUI, 10-ml plate) | 141 | 126-157 | 1.72 |

| Double quinate amt (60 μmol QUI, 10-ml plate) | 90 | 81-101 | 1.1 |

| Double plate vol (10 μmol SUC, 30 μmol QUI, 20-ml plate) | 91 | 82-102 | 1.11 |

| Double plate vol and quinate amt (10 μmol SUC, 60 μmol QUI, 20-ml plate) | 93 | 83-104 | 1.13 |

| Double inoculum (100 μl 10−3 overnight culture, 10 μmol SUC, 30 μmol QUI, 10-ml plate) | 80 | 71-91 | 0.98 |

In precision plating the total amount of a growth substrate per plate determines the amount of growth; therefore, for succinate (SUC) and quinate (QUI) the total amount per plate rather than the concentration is given. Plates were inoculated under standard conditions with 50 μl of a 10−3 dilution of an overnight culture.

Comparison of deletion frequency with frequency of other types of mutation.

Since the investigation was designed to determine limits imposed by sequence repetition on genetic stability, the frequency of several misalignment mutations giving rise to ΔpcaG1102 (Fig. 1) was compared with the frequency of reversion of small mutations inactivating pcaG. Frequencies for three of the latter mutations were assessed. As shown in Table 4, mutations requiring a base substitution, a single base insertion, or a single base deletion occurred, which gave rise to revertant colonies with a frequency of no greater than 1.5 per plate. With the caveat that the growth yield on plates may not be the same as that in liquid culture, this mutation frequency can be reported as 1.5 × 10−8. Included in Table 4 are results showing that deletion mutations apparently guided by sequence repetition occur with significantly higher frequency. For example, a sequence repetition of 8 bp in length and 12 bp apart in distance (indicated as L08-D12 in Table 4) gave rise to deletion mutant colonies with a frequency of 6.6 × 10−8.

TABLE 4.

Reversion frequencies of nonslippage and slippage mutations

| Strain | Genotype | Reversion frequency

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% confidence interval | ||

| ADP6407 | pcaH12 nonsense mutation | 1.5 | 0.83-2.47 |

| ADP6146 | pcaH18 1-base insertion | 0.17 | 0.02-0.6 |

| ADP6209 | pcaH20 1-base deletion | 0.08 | 0-0.46 |

| ADP7718 | pcaG7718 L13-D17 variant | 81 | 74-88 |

| ADP7739 | pcaG7739 L08-D12 variant | 6.6 | 4.9-8.6 |

| ADP7753 | pcaG7753 L16-D17 variant | 142 | 130-154 |

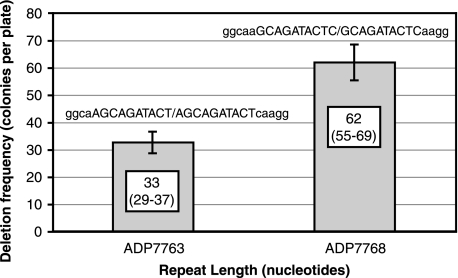

Deletion frequency is sequence dependent.

The primary objective of the investigation was to determine how the length of sequence repetitions and the distance between them influenced the frequency of deletions. A third factor, the nucleotide sequence in the repeated region, also can make a contribution, as demonstrated by the data reported in Fig. 3: 10-bp tandem duplications differing by a single nucleotide gave rise to deletions of twofold-lower frequency. It could therefore be expected that deletion frequency dependence on length and distance might represent general trends but not absolute values.

FIG. 3.

Deletion frequencies for two L10-D10 variants. The repeats have the same length and are both tandem duplications, yet they have different deletion rates. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

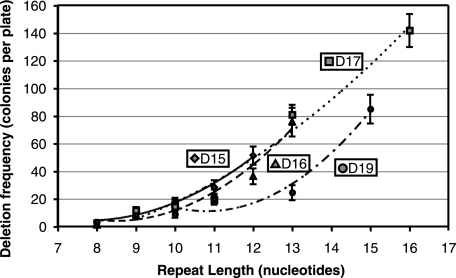

Overall assessment of contributions of repetition length and intervening distance to deletion formation.

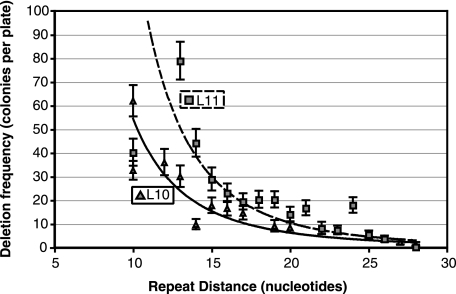

Measurements of the contributions of different patterns of sequence repetition to the frequency of deletion formation are presented in Table S2 in the supplemental material and summarized in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Two trends are evident. First, for repetitions separated by a constant distance, deletion frequency increased with increasing length. As shown in Fig. 4, the relationship is not linear, and curves to fit the data could be exponential or polynomial. In light of variations attributable to sequence variation, it would be unwise to place a mechanistic interpretation on the curves. Second, deletion between repetitions of constant length falls off sharply as the distance between them increases (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Influence of repeat length on deletion frequency. As indicated, repeat lengths with repeat distances (D) of 15, 16, 17, and 19 bp were examined. The general upwards trend is fit by a polynomial. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

FIG. 5.

Influence of repeat distance on deletion frequency. As indicated, repeat distance with repeat lengths (L) of 10 and 11 bp were examined. The general downwards trend is fit by a power law equation. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Limits of the contribution of nucleotide sequence repetition length and distance to deletion formation.

The data presented in Fig. S1 and Table S2 in the supplemental material allow two conclusions to be drawn about how sequence repetition can influence the frequency of deletion formation. As a lower limit, a sequence repetition of 8 bp or greater in length was required for deletion frequencies to rise significantly above 1.5 × 10−8, the threshold established for reversion of single-base-pair variations as presented in Table 2. The contribution of the other parameter, the distance between sequence repetitions, was more elusive. Deletions occurred with a frequency of 7.2 × 10−8 in strains containing repetitions of 12 bp in length separated by 30 bp (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Contributions of other genes to deletion formation.

Other investigations (4, 7, 32, 33) have shown that deletions between short and nearby sequence repetitions do not require recA, and the present investigation provides qualitative support for this conclusion. As shown in Table 5, inactivation of recA in strain ADP7786 did not prevent formation of the deletion mutation between repeated sequences. Recovery of mutant colonies was low in comparison with that from an organism containing the same repetition in a wild-type recA background (Table 5), but the low value could be attributed to the failure of the recA mutant to give rise to viable cells on precision plates. In keeping with the findings of others (3, 17), inactivation of MutS, which is known to guide repair of base mismatches and small bulges, did not have a significant effect on deletion formation (Table 5). RecG catalyzes fork reversal at stalled replication forks (43). Evidently, impairing this function leads to an increase in single-stranded DNA which can undergo slippage leading to mutation, because a recG-deficient mutant exhibited a twofold increase in the frequency of deletion (Table 5), similar to what was found in previous studies (5).

TABLE 5.

Effect of selected genes on deletion frequencya

| Strain | Genotype | No. of mutant colonies

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% confidence interval | Ratio to control value | ||

| ADP7718 | pcaG7718 control | 82 | 75-89 | 1 |

| ADP7786a | pcaG7718 ΔrecA::Ampr | 8.7 | 6.0-12 | 0.13 |

| ADP7787 | pcaG7718 ΔmutS::Str/Spr | 79 | 71-89 | 0.96 |

| ADP7785 | pcaG7718 ΔrecG2 | 166 | 145-187 | 2.1 |

| ADP7788 | pcaG7718; recG repaired | 69 | 57-81 | 0.91 |

Strain ADP7786 did not exhibit typical growth patterns, and the ratio for this strain is therefore not valid.

DISCUSSION

The 30-bp spontaneous deletion giving rise to ΔpcaG1102 from a wild-type background appeared to be sequence guided (Fig. 1). There is no reason to believe that the wild-type guiding sequence repetitions cause a genetic hot spot, because the mutation is only one of hundreds recovered after selection for strains with defects in pcaHG (18). More frequently occurring examples of spontaneous sequence-guided mutations are the 20-bp deletions, apparently guided by 10-bp perfect sequence repetitions, that predominate in causing defects interfering with expression of the pca operon (13). In this situation, the threshold for maintenance of genetic stability in the presence of sequence repetition appears to have been passed, and the 10-bp direct sequence repetitions appear to have been conserved only because they serve a beneficial function in regulation of pca gene expression.

The question to be addressed is how extensive sequence repetitions can be before they cause deletions to occur with frequencies that significantly exceed those for other kinds of spontaneous mutation. The experimental system based upon sequence-guided mutations giving rise to ΔpcaG1102 presents advantages because the unusual heat-sensitive phenotype it confers allows simple surveys to confirm that it indeed was the mutation that was selected. Additional significance comes from the broad biological distribution of pcaHG (8) and evidence that acquisition of sequence repetitions was an important step in evolution of the genes (22). Strain construction was simplified by the ease with which A. baylyi undergoes natural transformation and the distinctive metabolic system, which allow the design of precision plates.

Mutation frequencies from precision plates must be taken as approximations, because the cell number of 108 per plate is a rough estimate based on the amount of growth in liquid culture. In addition, cells growing on precision plates clearly are approaching starvation, and thus caution should be exercised in extrapolating the mutation frequencies observed in this study to those that occur in exponentially grown cultures. On the other hand, it is improbable that most mutations occurred in rapidly growing cell lines during evolution, and the relative deletion frequencies appear to give an accurate measure, over a range of more than 100-fold, of how the nature of sequence repetitions influences deletion frequencies. The major factors considered here were the lengths of repetitions and the distances between them, yet it must be noted that small differences in sequence had a twofold effect on deletion frequency.

With respect to the central question, i.e., how the properties of sequence repetitions may foster genetic instability, evidence emerges from identification of structures causing the frequency of sequence-guided deletions to be significantly above the frequency with which changes of a single base pair revert (Table 4). By this criterion, it appears that perfect repetitions of up to 7 bp are unlikely to foster deletions, that some instability is evident at 8 bp, and that at 9 bp or higher deletions will arise at a rate that would favor extinction in the absence of positive selection. It is difficult to draw an equally forceful conclusion about the contribution of the distance between repetitions. Sequence interactions leading to deletion were evident with repetitions separated by 30 bp, so a significant range of targets seems to be available if acquisition of sequence repetition is to be used as a mechanism for eliminating DNA that no longer serves a useful function.

The results described here with chromosomal A. baylyi pcaG support conclusions obtained with repetitions in plasmids (9), phages (40), and chromosomes (10) from other bacteria. In keeping with additional findings, sequence-guided deletions giving rise to ΔpcaG1102 were independent of MutS (3, 17) and, although only qualitative results were available for pcaG, RecA (10, 12). The twofold increase of sequence-guided deletion in a RecG background is consistent with the threefold increase observed with a similarly mutated E. coli strain (5) and suggests that defects in resolution of replication forks, the presumed consequence of RecG inactivation, increase the frequency of misalignment that can lead to deletion when replication proceeds. The annotated genome of A. baylyi (2) opens a direct avenue to investigation of the contributions of additional enzymes of DNA metabolism to sequence-guided deletion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sequencing services were provided by the Yale Keck Biotechnology Resource Lab. The A. baylyi genome sequence was provided by Genoscope. We thank Donna Parke and Alison Buchan for helpful suggestions.

This research was funded by grant GM063268 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, S. G., A. Zomorodipour, J. O. Andersson, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, U. C. Alsmark, R. M. Podowski, A. K. Naslund, A. S. Eriksson, H. H. Winkler, and C. G. Kurland. 1998. The genome sequence of. Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbe, V., D. Vallenet, N. Fonknechten, A. Kreimeyer, S. Oztas, L. Labarre, S. Cruveiller, C. Robert, S. Duprat, P. Wincker, L. N. Ornston, J. Weissenbach, P. Marliere, G. N. Cohen, and C. Médigue. 2004. Unique features revealed by the genome sequence of. Acinetobacter sp. ADP1, a versatile and naturally transformation competent bacterium. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:5766-5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayliss, C. D., T. van der Ven, and E. R. Moxon. 2002. Mutations in polI but not mutSLH destabilize Haemophilus influenzae tetranucleotide repeats. EMBO J. 21:1465-1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi, X., and L. F. Liu. 1994. recA-independent and. recA-dependent intramolecular plasmid recombination: differential homology requirement and distance effect. J. Mol. Biol. 235:414-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bierne, H., D. Villette, S. D. Ehrlich, and B. Michel. 1997. Isolation of a dnaE mutation which enhances RecA-independent homologous recombination in the Escherichia coli chromosome. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1225-1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bramhill, D., and A. Kornberg. 1988. A model for initiation at origins of DNA replication Cell 54:915-918. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bruand, C., V. Bidnenko, and S. D. Ehrlich. 2001. Replication mutations differentially enhance RecA-dependent and RecA-independent recombination between tandem repeats in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1248-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchan, A., E. L. Neidle, and M. A. Moran. 2001. Diversity of the ring-cleaving dioxygenase gene pcaH in a salt marsh bacterial community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5801-5809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bzymek, M., and S. T. Lovett. 2001. Instability of repetitive DNA sequences: the role of replication in multiple mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8319-8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chédin, F., E. Dervyn, R. Dervyn, S. D. Ehrlich, and P. Noirot. 1994. Frequency of deletion formation decreases exponentially with distance between short direct repeats. Mol. Microbiol. 12:561-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clopper, C. J., and E. S. Pearson. 1934. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika 26:404-413. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox, M. M. 1998. A broadening view of recombinational DNA repair in bacteria. Genes Cells 3:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Argenio, D. A., A. Segura, P. V. Bunz, and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Spontaneous mutations affecting transcriptional regulation by protocatechuate in Acinetobacter. FEMS Microbiol. 201:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Argenio, D. A., M. W. Vetting, D. H. Ohlendorf, and L. N. Ornston. 1999. Substitution, insertion, deletion, suppression, and altered substrate specificity in functional protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 181:6478-6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiMarco, A. A., B. A. Averhoff, E. E. Kim, and L. N. Ornston. 1993. Evolutionary divergence of pobA, the structural gene encoding p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase in an Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain well-suited for genetic analysis. Gene 125:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doten, R. C., L. A. Gregg, and L. N. Ornston. 1987. Cloning and genetic organization of the pca gene cluster from Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 169:3168-3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang, W. H., J. Y. Wu, and J. M. Su. 1997. Methyl-directed repair of mismatched small heterologous sequences in cell extracts from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22714-22720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerischer, U., and L. N. Ornston. 1995. Spontaneous mutations in pcaH and -G, structural genes for protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J. Bacteriol. 177:1336-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golding, G. B., and B. W. Glickman. 1985. Sequence-directed mutagenesis: evidence from a phylogenetic history of human alpha-interferon genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:8577-8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregg-Jolly, L. A., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. Properties of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus recA and its contribution to intracellular gene conversion. Mol. Microbiol. 12:985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harayama, S., M. Rekik, A. Bairoch, E. L. Neidle, and L. N. Ornston. 1991. Potential DNA slippage structures acquired during evolutionary divergence of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus chromsomal benABC and Pseudomonas putida TOL pWW0 plasmid xylXYZ, genes encoding benzoate dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 173:7540-7548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartnett, C., E. L. Neidle, K. L. Ngai, and L. N. Ornston. 1990. DNA sequences of genes encoding Acinetobacter calcoaceticus protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase: evidence indicating shuffling of genes and of DNA sequences within genes during their evolutionary divergence. J. Bacteriol. 172:956-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartnett, G. B., and L. N. Ornston. 1994. Acquisition of apparent DNA slippage structures during extensive evolutionary divergence of pcaD and catD genes encoding identical catalytic activities in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Gene 142:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The β-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones, R. M., and P. A. Williams. 2003. Mutational analysis of the critical bases involved in activation of the AreR-regulated σ54-dependent promoter in Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5627-5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juni, E. 1972. Interspecies transformation of. Acinetobacter: genetic evidence for a ubiquitous genus. J. Bacteriol. 112:917-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juni, E., and A. Janick. 1969. Transformation of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (Bacterium anitratum). J. Bacteriol. 98:281-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunkel, T. A. 1990. Misalignment-mediated DNA synthesis errors. Biochemistry 29:8003-8011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunkel, T. A., and A. Soni. 1988. Mutagenesis by transient misalignment. J. Biol. Chem. 263:14784-14789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levinson, G., and G. A. Gutman. 1987. Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:203-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovett, S. T. 2004. Encoded errors: mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1243-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovett, S. T., T. J. Gluckman, P. J. Simon, V. A. Sutera, Jr., and P. T. Drapkin. 1994. Recombination between repeats in Escherichia coli by a recA-independent, proximity-sensitive mechanism. Mol. Gen. Genet. 245:294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovett, S. T., R. L. Hurley, V. A. Sutera, Jr., R. H. Aubuchon, and M. A. Lebedeva. 2001. Crossing over between regions of limited homology in Escherichia coli: RecA-dependent and RecA-independent pathways. Genetics 160:851-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luria, S. E., and M. Delbrück. 1943. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28:491-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neidle, E. L., C. Hartnett, S. Bonitz, and L. N. Ornston. 1988. DNA sequence of the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus catechol 1,2-dioxygenase I structural gene catA: evidence for evolutionary divergence of intradiol dioxygenases by acquisition of DNA sequence repetitions. J. Bacteriol. 170:4874-4880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ornston, L. N., and W. K. Yeh. 1979. Origins of metabolic diversity: evolutionary divergence by sequence repetition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:3996-4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papworth, C., J. C. Bauer, J. Braman, and D. A. Wright. 1996. Site-directed mutagenesis in one day with >80% efficiency. Strategies 9:3-4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parke, D., and L. N. Ornston. 1984. Nutritional diversity of Rhizobiaceae revealed by auxanography. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:1743-1750. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peeters, B. P. H., J. H. de Boer, S. Bron, and G. Venema. 1988. Structural plasmid instability in Bacillus subtilis: effect of direct and inverted repeats. Mol. Gen. Genet. 212:450-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pierce, J. C., D. C. Kong, and W. Masker. 1991. The effect of the length of direct repeats and the presence of palindromes on deletion between directly repeated DNA sequences in bacteriophage-T7. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:3901-3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popp, R., T. Kohl, P. Patz, G. Trautwein, and U. Gerischer. 2002. Differential DNA binding of transcriptional regulator PcaU from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 184:1988-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosche, W. A., and P. L. Foster. 2000. Determining mutation rates in bacterial populations. Methods 20:4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singleton, M. R., S. Scaife, and D. B. Wigley. 2001. Structural analyis of DNA replication fork reversal by RecG. Cell 107:79-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tautz, D., M. Trick, and G. A. Dover. 1986. Cryptic simplicity in DNA is a major source of genetic variation. Nature 322:652-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trinh, T. Q., and R. R. Sinden. 1993. The influence of primary and secondary DNA structure in deletion and duplication between direct repeats in Escherichia coli. Genetics 134:409-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young, D. M., and L. N. Ornston. 2001. Functions of the mismatch repair gene mutS from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 183:6822-6831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young, D. M., D. Parke, and L. N. Ornston. 2005. Opportunities for genetic investigation afforded by Acinetobacter baylyi, a nutritionally versatile bacterial species that is highly competent for natural transformation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:519-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.