Abstract

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) are essential for the biosynthesis of the deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates of DNA. Recently, it was proposed that externally supplied deoxyribonucleosides or DNA is required for the growth of Bacillus subtilis under strict anaerobic conditions (M. J. Folmsbee, M. J. McInerney, and D. P. Nagle, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5252-5257, 2004). Cultivation of B. subtilis on minimal medium in the presence of oxygen indicators in combination with oxygen electrode measurements and viable cell counting demonstrated that growth occurred under strict anaerobic conditions in the absence of externally supplied deoxyribonucleosides. The nrdEF genes encode the only obvious RNR in B. subtilis. A temperature-sensitive nrdE mutant failed to grow under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, indicating that this oxygen-dependent class I RNR has an essential role under both growth conditions. Aerobic growth and anaerobic growth of the nrdE mutant were rescued by addition of deoxynucleotides. The nrd locus consists of an nrdI-nrdE-nrdF-ymaB operon. The 5′ end of the corresponding mRNA revealed transcriptional start sites 45 and 48 bp upstream of the translational start of nrdI. Anaerobic transcription of the operon was found to be dependent on the presence of intact genes for the ResDE two-component redox regulatory system. Two potential ResD binding sites were identified approximately 62 bp (site A) and 50 bp (site B) upstream of the transcriptional start sites by a bioinformatic approach. Only mutation of site B eliminated nrd expression. Aerobic transcription was ResDE independent but required additional promoter elements localized between 88 and 275 bp upstream of the transcriptional start.

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) provide all living organisms with the deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates required for DNA synthesis (16, 20). Three different classes of RNRs differ in the nature of free radical generation required for substrate activation. Class I RNRs, found in higher organisms and in many microorganisms, are oxygen dependent and generate a tyrosyl radical via a diiron-oxygen center and dioxygen. Class II enzymes, present in prokaryotes and a few lower eukaryotes, function during both aerobiosis and anaerobiosis. They employ adenosylcobalamin for radical formation. Class III reductases, employed exclusively by microorganisms with anaerobic metabolism, generate a glycyl radical from S-adenosylmethionine and an oxygen-sensitive iron-sulfur cluster (16). Based on polypeptide sequence homologies and their overall allosteric regulation behavior, class I RNRs have been further divided into class Ia enzymes, which are usually encoded by the nrdAB operon, and class Ib enzymes, which are encoded by a corresponding nrdEF operon (14, 15).

The observed differences in the oxygen dependence of the various types of RNRs in combination with the observed differential presence in bacteria may provide the organisms with an efficient mechanism for adaptation to changes in oxygen tension (34, 36). Consistent with this notion are the documented gene expression profiles of certain bacterial RNR-encoding genes in response to oxygen availability. Staphylococcus aureus nrdD is induced under anaerobic conditions (26). Pseudomonas stutzeri nrdD expression appears to be controlled by the Fnr-type oxygen regulator DnrS (42). The oxygen-dependent regulation of the nrdDG operon of Escherichia coli was also shown to be Fnr mediated (3). In many bacteria, including E. coli, two or even three loci for RNRs belonging to different classes coexist in the genome. Corresponding genes are coordinately expressed depending on the environment (17).

In Bacillus subtilis isolation and characterization of temperature-sensitive deoxyribonucleotide auxothrophic mutant ts-A13 led to identification of the nrd locus encoding a class Ib RNR (2). Mapping and sequencing of the ts13-A mutation locus led to identification of a point mutation in the nrdE gene, which alters the NrdE amino acid at position 255 from a histidine residue to a tyrosine residue. This amino acid change is thought to be responsible for an instable enzyme that causes the temperature-sensitive phenotype of the ts13-A mutant (39). The isolation of this conditional lethal mutant and the observation that all open reading frames of the nrd operon cannot be inactivated by insertional mutagenesis suggest that this operon is essential for biosynthesis of deoxyribonucleotides in B. subtilis (39). Sequence analysis of the genome revealed the absence of obvious additional RNR genes. However, homologs of nrdEF, designated bnrdEF (SPbeta nrdEF), were located in B. subtilis at 185° on the chromosome in the chromosomal segment corresponding to SPβ prophage. Each open reading frame harbors an intron and has been demonstrated to be not essential for the organism (22, 43). Sequence analysis of the B. subtilis genome revealed the absence of obvious additional RNR genes. Recently, the minimal essential genes of B. subtilis were identified as only 192 of 4,100 genes, and they included the class I ribonucleotide reductase genes nrdE and nrdF (19). The ymaA gene located upstream of nrdEF was found to be present also in the nrd loci of other bacilli. The deduced amino acid encoded by ymaA exhibits significant similarity to the NrdI product of a short open reading frame located upstream of the nrdEF operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and E. coli. NrdI has been demonstrated to be involved in RNR class Ib activity in these bacteria (13). In B. subtilis ymaA has been shown to be essential, and therefore, on the basis of the similarity found and genetic observations, B. subtilis ymaA was renamed nrdI (19).

Like other facultative anaerobes, B. subtilis grows readily in the absence of oxygen either by various modes of fermentation or by using nitrate as an alternative electron acceptor. The corresponding anaerobic physiology was established in detail by various investigations previously (4, 11, 24, 29, 32). The adaptation of B. subtilis to oxygen limitation in the environment is mediated by a complex regulatory network (23, 29, 32, 44). Currently, regulation at the transcriptional level is the part of this network that has been investigated best. The two-component regulatory system composed of the histidine sensor kinase ResE and the response regulator ResD has a pivotal role in the metabolic adjustment required for anaerobic growth using nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor (33, 40). ResD and ResE are required for transcription of genes involved in anaerobic nitrate respiration, including fnr (encoding the anaerobic gene regulator Fnr), nasDEF (nitrite reductase operon), and hmp (flavohemoglobin) (11, 21, 31, 33). Furthermore, ResD and ResE also play an important role in fermentative growth (4, 30), in which the regulatory genes are required for full induction of ldh (encoding lactate dehydrogenase) and lctP (lactate permease) expression (4).

In contrast to the observation made by several groups that investigated the anaerobic metabolism of B. subtilis, recently it was found that anaerobic growth of Bacillus mojavensis and B. subtilis 168 requires externally supplied deoxyribonucleosides or DNA (7). This finding and the presence of only the oxygen-dependent class I RNR encoded by the B. subtilis nrdEF genes gave rise to the question of how B. subtilis is able to grow under anaerobic conditions. Therefore, we analyzed the role of the nrdEF genes in the anaerobic growth of B. subtilis and studied the regulation of nrdEF transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All B. subtilis strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani medium was used for standard cultures of B. subtilis and E. coli unless indicated otherwise. For investigation of the expression of the various lacZ fusions and for preparation of RNA the strains were grown at 37°C on minimal medium (80 mM K2HPO4, 44 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM MgSO4 ·7H2O, 1.5 mM thiamine, 40 μM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 68 μM FeCl2 · 4H2O, 5 μM MnCl2 · 4H2O, 12.5 μM ZnCl2, 24 μM CuCl2 · 2H2O, 2.5 μM CoCl2 · 6H2O, 2.5 μM Na2 MoO4 · 2H2O, 50 mM glucose, 50 mM pyruvate, 1 mM l-tryptophan, 0.8 mM l-phenylalanine, 0.1% Casamino Acids); where indicated below, 10 mM nitrate was added. Minimal media employed for the oxygen tension-controlled anaerobic growth experiments were analyzed using standard methods to determine the presence of deoxynucleosides and DNA prior to use. B. subtilis 168 was adapted to anaerobic growth conditions in precultures and was transferred to strict anaerobic medium. Strict anaerobic conditions were verified by using the redox indicator resazurin at a concentration of 200 μg/liter, as well as oxygen electrode measurements in control experiments. Viable cell counting and live/dead staining were performed as described elsewhere (6). DNA concentrations were determined using a DNA DipStick kit (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) and Picoflour measurements based on the fluorescent dye Hoechst H 33258 (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, Calif.) by following the instructions provided by the manufacturers.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| B. subtilis strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | BGSCa |

| 168 | trpC2 | BGSC |

| PB1679 | ilvA-1 metB-5 ts-A13 | 18 |

| LAB2135 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet | 33 |

| THB2 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spec | 11 |

| MMB104 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan | 24 |

| BEH8 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::275nrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH9 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::87nrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH10 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spec amyE::87nrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH11 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet amyE::87nrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH12 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan amyE::87nrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH13 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::87mutAnrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

| BEH14 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::87mutBnrdI-lacZ cat | This study |

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center.

Northern blot analysis.

RNA was prepared as previously described (10). Northern blot analysis was performed as described elsewhere (5). A digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe was synthesized in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase, a 285-bp nrdE-specific PCR fragment as the template, and primers EH3 (5′-ACAGGCTTTCAGCAGATACG-3′) and EH4 (5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATTTAGATGTGCCGCTGAGTT-3′).

Identification of the nrdIEF transcriptional start site.

Fifty micrograms of RNA was used for primer extension analysis of the nrdIEF transcript. Reverse transcription was initiated from γ-32P-end-labeled primer EH5 (5′-CAAACCGCTGAACATTCCCTGTTTTCG-3′) by using a standard procedure (1). A DNA sequencing reaction using plasmid p275nrdI-lacZ as the template was performed with the same primer. The primer extension products and the sequencing reaction products were analyzed in parallel on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate buffer. The dried gel was analyzed with a phosphorimager.

Construction of the nrdI-lacZ reporter gene fusion.

Transcriptional fusions between the E. coli lacZ gene and B. subtilis nrdI upstream regions with various lengths were constructed. A 425-bp PCR fragment spanning the region from position −275 to position 130 relative to the transcriptional start site of nrdIEF was amplified using primers EH8 (5′-AGTTGAATTCGCGCGGATGTTGAAA-3′) and EH6 (5′-GCGAGGATCCACCTTGCGTATCTGC-3′). A 238-bp PCR fragment spanning the region from position −87 to position 130 was amplified using primers EH7 (5′-AGTTGAATTCCGTTTGCCTGATTTG-3′) and EH6. Using EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites integrated into the primers (underlined), the two amplified upstream regions of nrdIEF were cloned into plasmid pDIA5322, resulting in plasmids p275nrdI-lacZ and p87nrdI-lacZ, respectively (25). Both plasmids were transformed into B. subtilis strain JH642, and p87nrdI-lacZ was also transformed into B. subtilis LAB2135 (ΔresDE), THB2 (Δfnr), and MMB104 (ΔarfM); all transformants were screened for double-crossover integration at the amyE locus (11, 23, 33). The resulting strains, strains BEH9, BEH10, BEH11, BEH12, and BEH13, are described in Table 1.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the nrdIEF regulatory region.

The potential ResD binding sites of the nrdE promoter were changed from TTGATCAAAATAT to TCGATCGACCTAG (site A) and from GAATTTTTCATAAA to CAAGGTCTCATGAA (site B). A PCR was performed using the following primers containing the desired base changes (indicated by boldface type): EH90 (5′-AGTTGAATTCCGTTTGCCTGATTCGATCGACCTAGGAATTTTTCATAAAAACG-3′ for binding site A and EH92 (5′-AGTTGAATTCCGTTTGCCTGATTTGATCAAAATATCAAGGTCTCATGAAAACG-3′) for binding site B, both in combination with primer EH91 (5′-GCGAGGATCCACCTTGCGTATCTGCTGAAAG-3′). The resulting 238-bp mutated PCR fragments covered the promoter region found in p87nrdI-lacZ. Both PCR fragments were cloned into plasmid pDIA5322 as described above for the wild-type sequence, resulting in plasmids p87mutAnrdI-lacZ and p87mutBnrdI-lacZ, respectively. After transformation in B. subtilis strain JH642, strains BEH12 and BEH13 were obtained.

Measurement of β-galactosidase activity.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described previously (10) and was expressed in Miller units (27).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

B. subtilis grows under strict anaerobic conditions on minimal medium without the addition of deoxynucleotides or DNA.

In a recent paper Folmsbee et al. described the inability of B. subtilis 168 to grow under strict anaerobic conditions without addition of deoxynucleosides or DNA (7). In contrast to this observation, several other investigations during the last decade elucidated the exact nature of anaerobic nitrate respiratory and fermentative growth (4, 11, 12, 24, 29, 32). In most cases minimal medium without further addition of nucleosides or DNA was used. Nevertheless, we carefully reinvestigated the anaerobic growth of B. subtilis 168 and JH642 in a minimal medium by using absorbance at 578 nm, viable cell counting, and live/dead staining. Standard tests for the presence of deoxynucleosides and DNA failed to detect these compounds in the growth media employed. At the same time the oxygen tension of each culture was continuously monitored with a very sensitive oxygen electrode and was alternatively controlled by addition of the redox indicator resazurin. After approximately 5 min of anaerobic incubation of the cultures, the oxygen electrode failed to detect any residual amount of oxygen. In agreement, no oxygen-specific resazurin reaction was observed. Under these conditions both B. subtilis 168 and JH642 exhibited significant anaerobic growth using nitrate ammonification and mixed acid fermentation. The increase in the optical density was caused by viable B. subtilis cells. In agreement with various other publications, we observed strict anaerobic growth of B. subtilis on minimal medium without further addition of deoxynucleosides or DNA.

nrdE gene coding for a subunit of the oxygen-dependent ribonucleotide reductase is essential for anaerobic growth.

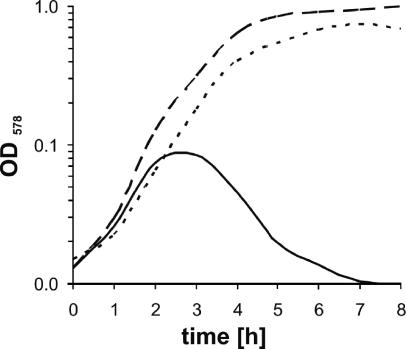

RNR enzymes are required for deoxynucleotide biosynthesis. Genome-wide searches identified the nrdEF genes as the sole RNR-encoding genes in B. subtilis. In order to determine the role of the nrdE gene in aerobic and anaerobic growth, we performed growth experiments using wild-type JH642 cells and the temperature-sensitive nrdE mutant ts-A13 of B. subtilis under aerobic and strict anaerobic conditions (18). First, at a nonpermissive temperature, 45°C, wild-type B. subtilis grew under strict anaerobic conditions on a minimal medium with 10 mM nitrate to a final optical density at 578 nm of 0.7. The growth of the nrdE temperature-sensitive B. subtilis ts-A13 mutant strain was drastically reduced. Addition of 100 μg deoxynucleosides per ml allowed B. subtilis strain ts-A13 to grow under strict anaerobic conditions at 45°C to levels even slightly above the wild-type strain levels (Fig. 1). Additionally, the cells were grown aerobically and anaerobically with addition of nitrate at 30°C. After 3 h, at the beginning of the exponential growth phase, wild-type and mutant cells were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature, 45°C. B. subtilis JH642 wild-type cells continued to grow under both conditions tested, whereas the nrdE ts-A13 mutant stopped growing and the number of ts-A13 cells decreased continuously during the following 3 h. This growth-deficient phenotype of the ts-A13 mutant was again rescued for both growth conditions by addition of deoxynucleotides to the medium. With addition of deoxynucleotides the ts-A13 mutant continued to grow like wild-type cells (data not shown). This observation indicates that the nrdE gene, to which the temperature-sensitive mutation was previously mapped, is essential for aerobic and anaerobic growth of B. subtilis.

FIG. 1.

Mutation of nrdEF genes eliminates anaerobic growth of B. subtilis. Strains were grown under strict anaerobic conditions in minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM nitrate. B. subtilis JH642 wild-type cells (dotted line) and the temperature-sensitive nrdE mutant ts-A13 (solid line) were grown at 45°C, the nonpermissive temperature of the mutant strain. Mutant strain PB1679 was rescued by addition of 100 μg ml−1 deoxynucleotides and grew like wild-type cells (dashed line). OD578, optical density at 578 nm.

How does the oxygen-dependent NrdEF function under anaerobic conditions? For E. coli NrdAB (8) and Lactococcus lactis NrdEF (14), both class I RNRs, it was shown that an enzyme radical was regenerated after every round of catalysis. Molecular oxygen is not required. We propose a similar mechanism for the B. subtilis RNR encoded by nrdEF that sustains anaerobic growth of B. subtilis. Similarly, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa class I RNR activity was found to be significantly increased under microaerobic conditions (17). E. coli nrdDG mutants grow well under oxygen-limiting conditions solely due to the presence of the oxygen-dependent enzyme NrdEF (8).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae the oxygen-dependent coproporphyrinogen oxidase encoded by the HEM13 gene, a heme biosynthesis enzyme, is the major protein produced under anaerobic conditions. This sole coproporphyrinogen III oxidase of yeast is essential for anaerobic growth of the organism (45). Similarly, the hemF gene encoding the analogous enzyme of P. aeruginosa was found to be strongly induced under anaerobic conditions (37).

Analysis of the B. subtilis nrd operon structure.

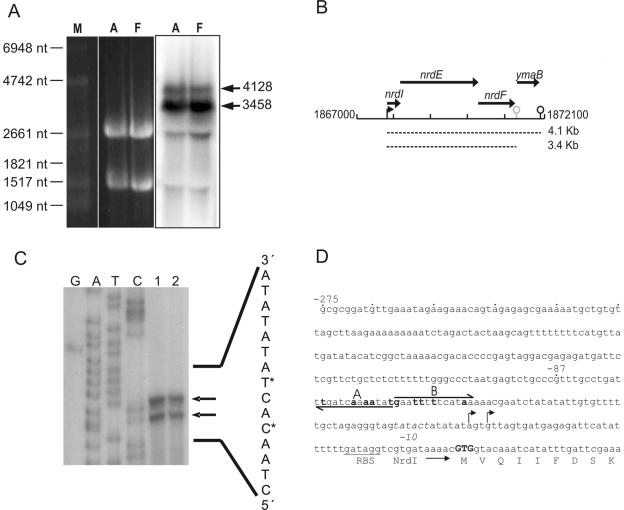

A distinct feature of all known class Ib RNR operons is that they encode, in addition to the RNR subunits, the small protein NrdI, whose function is unknown. Moreover, often a fourth gene encoding the electron transfer protein NrdH is found. Therefore, class Ib nrd genes are typically arranged in an nrdH-nrdI-nrdE-nrdF operon (41). We analyzed the operon structure of the B. subtilis nrd locus by Northern blot analysis using RNA prepared from cells grown under aerobic and strict anaerobic conditions. Equal amounts of a major transcript that was approximately 3,500 nucleotides long and a minor transcript that was about 4,100 nucleotides long were detected for both growth conditions using an nrdE-specific hybridization probe (Fig. 2A and B). The size of the major band corresponded nicely to the size of the nrdIEF transcript, whereas the larger transcript contained additional mRNA of the following ymaB open reading frame. These data confirm that the terminator structure annotated in the nrdF-ymaB intercistronic region is used in vivo (39).

FIG. 2.

Ribonucleotide reductase genes of B. subtilis are transcribed in an nrdIEF ymaB operon. (A) Ten micrograms of total RNA was separated on a 1% denaturing agarose gel and analyzed by Northern blotting. An nrdE-specific RNA probe was used for hybridization. Two transcripts were detected in RNA from aerobically grown cells (lanes A) and fermentatively grown cells (lanes F); the position of a major ca. 3,400-nucleotide transcript whose size corresponded to the size of an nrdIEF transcript and the position of a minor 4,100-nucleotide transcript corresponding to an nrdIEF ymaB operon are indicated by arrows. The size standards were ethidium bromide-stained 16S and 23S rRNA species and RNA molecular weight marker no. 1 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) (lane M). nt, nucleotide. (B) Schematic representation of the nrdIEF ymaB region. The coding regions of the genes are indicated by arrows. The proposed transcriptional start point and termination signals are indicated by a small arrow and hairpin structures, respectively. The transcripts determined are indicated by dashed lines. The numbering corresponds to the numbering of the genomic sequence. (C) Determination of the transcription start site of nrdIEF by primer extension analysis. Total RNA was isolated from JH642 cells grown aerobically (lane 1) and under fermentative conditions (lane 2) and was analyzed. The same primer used for the primer extension analysis was used for sequencing reactions (lanes G, A, T, and C). The arrows indicate the positions of primer extension products, and asterisks indicate the 5′ end of the nrdIEF mRNA in the sequence. (D) Promoter sequences of the nrdI promoter fused to the lacZ reporter gene. The 5′ ends of the promoter fragments are labeled −275 and −87. The arrows indicate the locations and orientations of potential ResD binding sites A and B, and the bases changed for mutagenesis of the binding site are indicated by boldface type. Transcriptional start sites are indicated by arrows. The sequence of the −10 region is in italics. A potential ribosome binding site (RBS) is underlined. The start codon of NrdI is indicated by boldface type.

An nrdH homologue gene encoding glutaredoxin is not part of the B. subtilis nrd locus and is not present in the B. subtilis genome. The yosR gene, encoding a glutaredoxin-like protein and located near the SPbeta bnrdEF operon, has been found to be dispensable (43). On the other hand, the observation that the trxA thioredoxin gene is essential for B. subtilis and is induced under various stress conditions suggests that TrxA is the only electron donor essential for RNR reduction in B. subtilis (38). The nrdIEF operon structure was also found in the Bacillus cereus and Bacillus anthracis chromosomes. However, in these organisms nrdH was found elsewhere in the genome.

Promoter structure and expression of the nrd operon.

The 5′ ends of the two observed nrd operon transcripts were mapped 45 bp and 48 bp upstream of the GTG start codon of nrdI using the primer extension technique (Fig. 2C). Upstream of the transcriptional start sites a potential −10 region comprises an 11-bp AT-rich DNA stretch. To determine the promoter sequences necessary for anaerobic expression of nrdIEF, we cloned two promoter fragments different in length upstream of a promoterless E. coli lacZ reporter gene. Plasmid p275nrdI-lacZ, containing 275 bp upstream and 130 bp downstream of the transcriptional start site and plasmid p87nrdI-lacZ containing 87 bp upstream and 130 bp downstream of the start site were integrated into the amyE locus of B. subtilis JH642 wild-type cells. The cells were grown under aerobic and strict anaerobic fermentative and nitrate respiratory conditions, and lacZ expression was analyzed. There was no obvious difference in β-galactosidase activities when we compared the expression of the 275nrdI-lacZ reporter gene fusion under the three aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions (Table 2). Surprisingly, expression of the 87nrdI-lacZ reporter gene fusion in wild-type cells was reduced four- to fivefold under aerobic growth conditions compared to the expression under both the anaerobic growth conditions used (Table 2). These results indicated that although the overall nrdIEF transcription levels under aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions are comparable, aerobic transcription and anaerobic transcription are mediated by different regulatory sequences. Clearly, the short promoter region does not contain sequences required for aerobic induction, whereas sequences necessary for anaerobic induction are present. The primer extension and Northern signals that were the same strength for RNA prepared from aerobically and anaerobically grown cultures indicated that the transcription start site and products were identical. In agreement, reexamination of the longer 275-bp upstream region did not reveal additional transcriptional start points. Therefore, aerobic nrd operon transcription and anaerobic nrd operon transcription start at the same site.

TABLE 2.

Anaerobic expression of nrdI-lacZ is dependent on ResD

| Reporter gene fusion | Strain (relevant genotype) | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic conditions | Anaerobic conditions

|

|||

| Fermentative | With nitrate | |||

| 275nrdI-lacZ | BEH8 (wild type) | 82 | 85 | 103 |

| 87nrdI-lacZ | BEH9 (wild type) | 15 | 99 | 102 |

| BEH11 (resDE) | 10 | 13 | 15 | |

| BEH10 (fnr) | 9 | 81 | 86 | |

| BEH12 (arfM) | 25 | 118 | 119 | |

| 87mutA nrdI-lacZ | BEH13 (wild type) | 15 | 43 | 32 |

| 87mutB nrdI-lacZ | BEH14 (wild type) | 9 | 17 | 7 |

β-Galactosidase activities were measured during the exponential growth phase under aerobic and anaerobic fermentative growth conditions with addition of 10 mM nitrate where indicated. The results are the averages of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate, and the standard deviation was less than 10%.

Anaerobic transcription of the nrd operon is dependent on resDE.

Since we were interested in the anaerobic formation of RNR in B. subtilis, we focused on the anaerobic control of the nrd operon promoter. To obtain further insight into anaerobic regulation of nrdI operon expression, the 87nrdI-lacZ construct was introduced into a resDE mutant strain. The ResE/ResD two-component regulatory system has a pivotal role in the metabolic adjustment required for anaerobic growth. The anaerobic expression of the 87nrd-lacZ reporter gene fusion was significantly reduced in the resDE mutant strain compared to the expression in the wild-type cells, indicating that resDE is important for anaerobic expression of the nrd operon (Table 2). In E. coli anaerobic nrdG expression was shown to be fnr dependent (3). However, mutations in B. subtilis fnr did not have a significant effect on nrdI-lacZ expression. In agreement with this finding, no obvious Fnr binding site was detected in the nrdI promoter region. A recent transcriptome analysis confirmed this observation (35). The level of expression of 87nrdI-lacZ in an arfM mutant strain was similar to the wild-type level as well (Table 2). These results indicate that ResDE does not exert its inducing effect through a regulatory cascade involving Fnr or ArfM.

We used the Virtual Footprint tool of the PRODORIC database (9, 28) to find potential binding sites for ResD in the nrdI promoter sequence present in 87nrdI-lacZ and found two regions with rather low levels of similarity. One region was in the noncoding strand at position −63 to position −75 with respect to the transcriptional start site (binding site A), and one region was in the coding strand at position −62 to position −49 with respect to the transcriptional start site (binding site B) (Fig. 2D). We mutated both potential ResD binding sites in the context of the 87nrdI-lacZ construct via exchange of several base pairs.

We observed only a slight reduction in anaerobic nrdI-lacZ expression when binding site A was mutated. In contrast to this observation, ResDE-dependent anaerobic nrdI-lacZ induction was eliminated after mutation of binding site B (Table 2). Due to the poor conservation of both potential ResD binding sites, these results left us with two options. First, binding site B may represent a true binding site for ResD in the promoter. Second, ResD may act indirectly via a second, unknown regulator whose corresponding binding site was affected by the mutations.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (HA3456/1-2).

We thank M. Nakano for her gift of strain LAB2135.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Bazill, G. W. 1972. Temperature-sensitive mutants of B. subtilis defective in deoxyribonucleotide synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 117:19-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boston, T., and T. Atlung. 2003. FNR-mediated oxygen-responsive regulation of the nrdDG operon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5310-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz-Ramos, H., T. Hoffmann, M. Marino, H. Nedjari, E. Presecan-Siedel, O. Dreesen, P. Glaser, and D. Jahn. 2000. Fermentative metabolism of Bacillus subtilis: physiology and regulation of gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 182:3072-3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engler-Blum, G., M. Meier, J. Frank, and G. A. Muller. 1993. Reduction of background problems in nonradioactive Northern and Southern blot analyzes enables higher sensitivity than 32P-based hybridizations. Anal. Biochem. 210:235-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eschbach, M., K. Schreiber, K. Trunk, J. Buer, D. Jahn, and M. Schobert. 2004. Long-term anaerobic survival of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa via pyruvate fermentation. J. Bacteriol. 186:4596-4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Folmsbee, M. J., M. J. McInerney, and D. P. Nagle. 2004. Anaerobic growth of Bacillus mojavensis and Bacillus subtilis requires deoxyribonucleosides or DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5252-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garriga, X., R. Eliasson, E. Torrents, A. Jordan, J. Barbe, I. Gibert, and P. Reichard. 1996. nrdD and nrdG genes are essential for strict anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 229:189-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grote, A., K. Hiller, M. Scheer, R. Münch, B. Nortemann, D. C. Hempel, and D. Jahn. 2005. JCat: a novel tool to adapt codon usage of a target gene to its potential expression host. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W526—W531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Härtig, E., H. Geng, A. Hartmann, A. Hubacek, R. Munch, R. W. Ye, D. Jahn, and M. M. Nakano. 2004. Bacillus subtilis ResD induces expression of the potential regulatory genes yclJK upon oxygen limitation. J. Bacteriol. 186:6477-6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann, T., N. Frankenberg, M. Marino, and D. Jahn. 1998. Ammonification in Bacillus subtilis utilizing dissimilatory nitrite reductase is dependent on resDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:186-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann, T., B. Troup, A. Szabo, C. Hungerer, and D. Jahn. 1995. The anaerobic life of Bacillus subtilis: cloning of the genes encoding the respiratory nitrate reductase system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 131:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan, A., F. Aslund, E. Pontis, P. Reichard, and A. Holmgren. 1997. Characterization of Escherichia coli NrdH. A glutaredoxin-like protein with a thioredoxin-like activity profile. J. Biol. Chem. 272:18044-18050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan, A., E. Pontis, F. Aslund, U. Hellman, I. Gibert, and P. Reichard. 1996. The ribonucleotide reductase system of Lactococcus lactis. Characterization of an NrdEF enzyme and a new electron transport protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:8779-8785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan, A., E. Pontis, M. Atta, M. Krook, I. Gibert, J. Barbe, and P. Reichard. 1994. A second class I ribonucleotide reductase in Enterobacteriaceae: characterization of the Salmonella typhimurium enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12892-12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan, A., and P. Reichard. 1998. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67:71-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan, A., E. Torrents, I. Sala, U. Hellman, I. Gibert, and P. Reichard. 1999. Ribonucleotide reduction in Pseudomonas species: simultaneous presence of active enzymes from different classes. J. Bacteriol. 181:3974-3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karamata, D., and J. D. Gross. 1970. Isolation and genetic analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants of B. subtilis defective in DNA synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 108:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi, K., S. D. Ehrlich, A. Albertini, G. Amati, K. K. Andersen, M. Arnaud, K. Asai, S. Ashikaga, S. Aymerich, P. Bessieres, F. Boland, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, K. Bunai, J. Chapuis, L. C. Christiansen, A. Danchin, M. Debarbouille, E. Dervyn, E. Deuerling, K. Devine, S. K. Devine, O. Dreesen, J. Errington, S. Fillinger, S. J. Foster, Y. Fujita, A. Galizzi, R. Gardan, C. Eschevins, T. Fukushima, K. Haga, C. R. Harwood, M. Hecker, D. Hosoya, M. F. Hullo, H. Kakeshita, D. Karamata, Y. Kasahara, F. Kawamura, K. Koga, P. Koski, R. Kuwana, D. Imamura, M. Ishimaru, S. Ishikawa, I. Ishio, D. Le Coq, A. Masson, C. Mauel, R. Meima, R. P. Mellado, A. Moir, S. Moriya, E. Nagakawa, H. Nanamiya, S. Nakai, P. Nygaard, M. Ogura, T. Ohanan, M. O'Reilly, M. O'Rourke, Z. Pragai, H. M. Pooley, G. Rapoport, J. P. Rawlins, L. A. Rivas, C. Rivolta, A. Sadaie, Y. Sadaie, M. Sarvas, T. Sato, H. H. Saxild, E. Scanlan, W. Schumann, J. F. Seegers, J. Sekiguchi, A. Sekowska, S. J. Seror, M. Simon, P. Stragier, R. Studer, H. Takamatsu, T. Tanaka, M. Takeuchi, H. B. Thomaides, V. Vagner, J. M. van Dijl, K. Watabe, A. Wipat, H. Yamamoto, M. Yamamoto, Y. Yamamoto, K. Yamane, K. Yata, K. Yoshida, H. Yoshikawa, U. Zuber, and N. Ogasawara. 2003. Essential Bacillus subtilis genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:4678-4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolberg, M., K. R. Strand, P. Graff, and K. K. Andersson. 2004. Structure, function, and mechanism of ribonucleotide reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1699:1-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaCelle, M., M. Kumano, K. Kurita, K. Yamane, P. Zuber, and M. M. Nakano. 1996. Oxygen-controlled regulation of the flavohemoglobin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3803-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarevic, V., B. Soldo, A. Dusterhoft, H. Hilbert, C. Mauel, and D. Karamata. 1998. Introns and intein coding sequence in the ribonucleotide reductase genes of Bacillus subtilis temperate bacteriophage SPbeta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1692-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marino, M., T. Hoffmann, R. Schmid, H. Mobitz, and D. Jahn. 2000. Changes in protein synthesis during the adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to anaerobic growth conditions. Microbiology 146:97-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marino, M., H. C. Ramos, T. Hoffmann, P. Glaser, and D. Jahn. 2001. Modulation of anaerobic energy metabolism of Bacillus subtilis by arfM (ywiD). J. Bacteriol. 183:6815-6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin-Verstraete, I., M. Debarbouille, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1992. Mutagenesis of the Bacillus subtilis “−12, −24” promoter of the levanase operon and evidence for the existence of an upstream activating sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 226:85-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masalha, M., I. Borovok, R. Schreiber, Y. Aharonowitz, and G. Cohen. 2001. Analysis of transcription of the Staphylococcus aureus aerobic class Ib and anaerobic class III ribonucleotide reductase genes in response to oxygen. J. Bacteriol. 183:7260-7272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 28.Munch, R., K. Hiller, H. Barg, D. Heldt, S. Linz, E. Wingender, and D. Jahn. 2003. PRODORIC: prokaryotic database of gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:266-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakano, M., and P. Zuber. 2001. Anaerobiosis, p. 393-404. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 30.Nakano, M. M., Y. P. Dailly, P. Zuber, and D. P. Clark. 1997. Characterization of anaerobic fermentative growth of Bacillus subtilis: identification of fermentation end products and genes required for growth. J. Bacteriol. 179:6749-6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakano, M. M., T. Hoffmann, Y. Zhu, and D. Jahn. 1998. Nitrogen and oxygen regulation of Bacillus subtilis nasDEF encoding NADH-dependent nitrite reductase by TnrA and ResDE. J. Bacteriol. 180:5344-5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakano, M. M., and P. Zuber. 1998. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 52:165-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano, M. M., P. Zuber, P. Glaser, A. Danchin, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:3796-3802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poole, A. M., D. T. Logan, and B. M. Sjoberg. 2002. The evolution of the ribonucleotide reductases: much ado about oxygen. J. Mol. Evol. 55:180-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reents, H., R. Münch, T. Dammeyer, D. Jahn, and E. Härtig. 2006. The Fnr regulon of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:1103-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reichard, P. 2002. Ribonucleotide reductases: the evolution of allosteric regulation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 397:149-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rompf, A., C. Hungerer, T. Hoffmann, M. Lindenmeyer, U. Romling, U. Gross, M. O. Doss, H. Arai, Y. Igarashi, and D. Jahn. 1998. Regulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa hemF and hemN by the dual action of the redox response regulators Anr and Dnr. Mol. Microbiol. 29:985-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scharf, C., S. Riethdorf, H. Ernst, S. Engelmann, U. Volker, and M. Hecker. 1998. Thioredoxin is an essential protein induced by multiple stresses in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 180:1869-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scotti, C., A. Valbuzzi, M. Perego, A. Galizzi, and A. M. Albertini. 1996. The Bacillus subtilis genes for ribonucleotide reductase are similar to the genes for the second class I NrdE/NrdF enzymes of Enterobacteriaceae. Microbiology 142:2995-3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun, G., E. Sharkova, R. Chesnut, S. Birkey, M. F. Duggan, A. Sorokin, P. Pujic, S. D. Ehrlich, and F. M. Hulett. 1996. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1374-1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torrents, E., I. Roca, and I. Gibert. 2003. Corynebacterium ammoniagenes class Ib ribonucleotide reductase: transcriptional regulation of an atypical genomic organization in the nrd cluster. Microbiology 149:1011-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vollack, K. U., E. Härtig, H. Körner, and W. G. Zumft. 1999. Multiple transcription factors of the FNR family in denitrifying Pseudomonas stutzeri: characterization of four fnr-like genes, regulatory responses and cognate metabolic processes. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1681-1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westers, H., R. Dorenbos, J. M. van Dijl, J. Kabel, T. Flanagan, K. M. Devine, F. Jude, S. J. Seror, A. C. Beekman, E. Darmon, C. Eschevins, A. de Jong, S. Bron, O. P. Kuipers, A. M. Albertini, H. Antelmann, M. Hecker, N. Zamboni, U. Sauer, C. Bruand, D. S. Ehrlich, J. C. Alonso, M. Salas, and W. J. Quax. 2003. Genome engineering reveals large dispensable regions in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:2076-2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye, R. W., W. Tao, L. Bedzyk, T. Young, M. Chen, and L. Li. 2000. Global gene expression profiles of Bacillus subtilis grown under anaerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 182:4458-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zagorec, M., J. M. Buhler, I. Treich, T. Keng, L. Guarente, and R. Labbe-Bois. 1988. Isolation, sequence, and regulation by oxygen of the yeast HEM13 gene coding for coproporphyrinogen oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 263:9718-9724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]