Abstract

Cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) is a newly identified virulence factor produced by several pathogenic bacteria implicated in chronic infection. Seventy three strains of periodontopathogenic bacteria were examined for the production of CDT by a HeLa cell bioassay and for the presence of the cdt gene by PCR with degenerative oligonucleotide primers, which were designed based on various regions of the Escherichia coli and Campylobacter cdtB genes, which have been successfully used for the identification and cloning of cdtABC genes from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans Y4 (M. Sugai et al., Infect. Immun. 66:5008-5019, 1998). CDT activity was found in culture supernatants of 40 of 45 tested A. actinomycetemcomintans strains, but the titer of the toxin varied considerably among these strains. PCR experiments indicated the presence of Y4-type cdt sequences in these strains, but the rest of A. actinomycetemcomitans were negative by PCR amplification and also by Southern blot analysis for the cdtABC gene. In the 40 CDT-positive strains, Southern hybridization with HindIII-digested genomic DNA revealed that there are at least 6 restriction fragment length polymorphism types. This suggests that the cdtABC flanking region is highly polymorphic, which may partly explain the variability of the CDT activity in the culture supernatants. The rest of tested strains of periodontopathogenic bacteria did not have detectable CDT production by the HeLa cell assay and for cdtB sequences by PCR analysis under our experimental conditions. These results strongly suggested that CDT is a unique toxin predominantly produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans among periodontopathogenic bacteria.

Periodontitis is a destructive inflammatory response affecting the tooth-supporting tissues. Etiological and microbiological studies have well established that dental plaque, a composite of microorganisms and their products, plays a major role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis (2, 34). Previous evidence suggests that it participates in promoting inflammation of gingival tissue through direct cytotoxicity and indirect immune-mediated responses (33). A variety of bacterial products in dental plaque have been implicated in this process. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans has been suspected to be one of the key pathogens in the etiology of human periodontitis (30, 34). It produces a variety of virulence factors including cytotoxic factors (2, 8-12, 17, 19, 28, 31), chemotactic inhibitors (33), collagenases (24), and lipopolysaccharides (13, 25). Among the cytotoxic factors, leukotoxin has been the most extensively studied (14-16, 18). Recently, we and others discovered another cytotoxic factor which shows cell cycle-specific growth inhibitory activity as a new member of the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) family in A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 (18, 28, 32). The CDTs are produced by a variety of bacterial genera and form a heterogeneous family of toxins with similar biological activities (4, 20, 23, 26). The term CDT was designated for an activity that induces progressive cell distension and eventual cytotoxicity in cultured cells (5, 21, 22).

Since CDT is a newly identified virulence factor produced by a periodontopathogen, A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4, we questioned whether any other periodontopathogenic bacterial strains produce CDT and possess cdt genes. We herein report that a HeLa cell bioassay indicated the production of CDT in all tested strains of A. actinomycetemcomitans. PCR and Southern blot experiments indicated the presence of the Y4-type cdtABC sequence in 40 of 45 strains. On the other hand, the rest of the tested strains produced little or no CDT activity and were negative for the PCR experiments. These results strongly suggest that cdt genes are prevalent in A. actinomycetemcomitans, which secrete CDT into the culture supernatant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and chemicals.

Restriction enzymes were from Boehringer Mannheim, Tokyo, Japan, or New England BioLabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass. Other materials and chemicals used were from other commercial sources as stated below.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study were isolates from periodontitis patients (Table 1). All isolates were minimally passaged in culture media and stored at −80°C until use. The culture media for periodontopathogenic bacteria are as follows (per liter): A. actinomycetemcomitans, 10 g of Trypticase soy broth (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), 1% yeast extract, 1% agar; Porphyromonas and Prevotella species, 30 g of Trypticase soy broth, 1% yeast extract, 5 mg of hemin, 1 mg of vitamin K3, 5% sheep blood, 1% agar; Capnocytophaga species and Fusobacterium nucleatum, 10 g of Trypticase soy broth, 1% yeast extract, 2 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of glucose, 5% sheep blood, 1% agar; Eikenella corrodens, 30 g of Trypticase soy broth, 2 g of KNO, 5 mg of hemin, 5% sheep blood, 1% agar; Campylobacter rectus, 10 g of Trypticase peptone (BBL), 3 g of Phytone peptone (Difco Laboratory, Detroit, Mich.), 2 g of yeast extract, 2 g of NaCl, 4 g of asparagine, 4 g of sodium fumarate, 3 g of sodium formate. These bacteria were grown at 37°C in a CO2-rich atmosphere with an AnaeroPack (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan). In the case of A. actinomycetemcomitans, tryptone-yeast extract broth was used when necessary. All clinically isolated A. actinomycetemcomitans were checked by PCR to ascertain the presence of the 16S rRNA and the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific outer membrane protein (Omp29) gene.

TABLE 1.

Periodontopathogenic bacteria used in this study

| Bacterium | Source | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strain Y4 | Standard strain | |

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | Clinical isolates | 45 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | Clinical isolates | 13 |

| Prevotella intermedia | Clinical isolates | 14 |

| Prevotella denticola | Clinical isolate | 1 |

| Prevotella melaninogenica | Clinical isolate | 1 |

| Prevotella oralis | Clinical isolate | 1 |

| Prevotella heparinolytica | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Prevotella buccae | Clinical isolate | 1 |

| Prevotella nigrescens | Clinical isolate | 1 |

| Capnocytophage gingivalis | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Capnocytophage ochracea | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Capnocytophage sputigena | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Capnocytophage sp.a | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | Clinical isolates | 5 |

| Eikenella corrodens | Clinical isolates | 3 |

| Haemophilus aphrophilus | Clinical isolates | 2 |

| Campylobacter rectus | Clinical isolates | 5 |

Species was unidentified.

Cells and culture conditions.

HeLa cells (ATCC CCL2) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere.

Detection of cytodistending activity in bacterial sterile lysates and culture supernatant.

Bacterial cells were cultured in anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 2 to 3 days and harvested when the optical density at 660 nm reached 0.4 to 0.5. Bacterial cells were recovered from the culture broth or plate and resuspended in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0). The cell suspension was lysed by periodic sonication for 30 s six times on ice (Ultradysruptor; TOMY Seiko, Tokyo, Japan). After clarification by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 20 min), lysates were filtered (0.2-μm-pore-size filters) and the protein concentration was determined. Then the protein concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/ml with PBS. A portion was placed onto HeLa cell monolayers in a 48-well plate (1.6 × 103 cells per well) (Falcon; Becton Dickinson). Cytodistending activity was titrated by using as the endpoint the highest twofold dilution of toxic material giving 50% transformed cells after 72 h of incubation, and 1 U of CDT activity was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution. The inhibitory effect of the cytodistension with anti-CDTC serum was measured as described previously (32). Briefly, HeLa cells were pretreated with a 1/100 dilution of rabbit anti-CDTC serum. Then culture supernatant or sonic lysate was added to the culture. After 72 h of incubation, CDT activity was measured.

DNA manipulations.

Routine DNA manipulations, DNA digestion with restriction enzymes, gel electrophoresis, Southern blotting of DNA, and hybridization were performed essentially as described previously (32). Purification of chromosomal DNA from bacteria was performed with the DNA extraction kit from Gentra, Minneapolis, Minn., and by following the instruction manual. Hybridization was performed by means of an enhanced chemiluminescence procedure (ECL direct labeling kit or 3′ oligolabeling kit; Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

PCR.

PCR reagents were from Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, Conn.), and PCR was performed with the GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer). The primers were supplied by Espec Oligo Service, Co., Ibaragi, Japan. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea (5′-3′) | Characteristic (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| MIX5′ | GAAARYAAATGGARYRYWMRTGTMMG | Y4 cdtB degenerative primer (32) |

| MiX3′ | AAATCWCCWRSAATCATCCAGTTA | Y4 cdtB degenerative primer (32) |

| QIA-U | AGGTACCATGGAAAAGTTT | Y4 cdtA start region (this study) |

| QIC-L | AAAGATCTGCTACCCTGA | Y4 cdtC stop region (this study) |

| U-0007 | GAAGCTCCCAAGAACGCTCA | Y4 orf1 start region (this study) |

| L-0305 | CTCTTGAAGAAGTCAATGAA | Y4 orf1 HindIII region (this study) |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans 16S-U | GCTAATACCGCGTAGAGTCGG | A. actinomycetemcomitans 16S rRNA gene unique area |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans 16S-R | ATTTCACACCTCACTTAAAGGT | A. actinomycetemcomitans 16S rRNA gene unique area |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans omp-U | CCACAAGCAAACACTTTC | A. actinomycetemcomitans omp29 5′ region (this study) |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans omp-R | ACCGAATGCGAAAGT | A. actinomycetemcomitans omp29 middle region (this study) |

R is A or G, Y is C or T, M is A or C, W is A or T, and S is G or C.

Cell cycle analysis.

The cell cycle was analyzed by propidium iodide staining of HeLa cells and flow cytometry (32). Briefly, after trypsinization and washing HeLa cells with PBS, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol. After fixation, cells were rehydrated in PBS and permeabilized with Triton X-100. Propidium iodide (10 μg/ml) and RNase (1 mg/ml) were added to the cells and incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Flow cytometry analysis was carried out by FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson). The data were analyzed with Cell Quest software.

Other procedures.

Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad (Richmond, Calif.) protein assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

RESULTS

CDT production in periodontopathogenic bacteria.

Previous studies demonstrated that A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 produces CDT and possesses cdt genes (32). We therefore screened a variety of bacterial strains which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases for the production of CDT activity. Initially, we simply tested whether CDT activity was produced in cell lysates without titrating the amount of the activity produced by the variety of strains cultured on agar plates. It was apparent that most of the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains tested produced a CDT activity. On the other hand, the rest of tested strains produced little (less than 32 U) or no CDT activity at all. It was noted that the lysate of Capnocytophaga strains showed cytotoxic activity, but none of them showed any cytodistending activity.

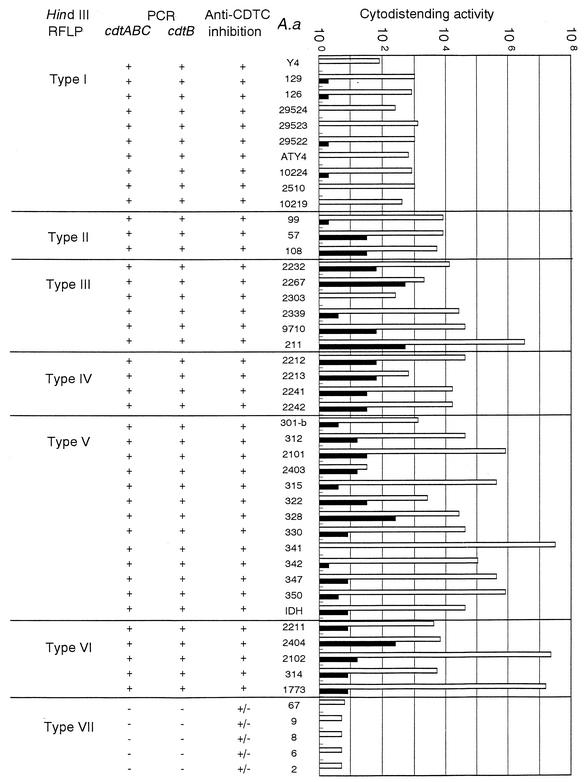

We next tried to quantitate the relative amount of CDT activity produced by the 46 A. actinomycetemcomitans strains, including the standard strain Y4. We titrated the activity in cell lysates and in the culture supernatants of each strain. As shown in Fig. 1, CDT activity was recovered from both the cell lysate and culture supernatant. The mean titer of the bacterial cell lysate varied among strains ranging from 1 to 512 U. There were several strains which produced titers higher than 1 × 106 U while others produced titers as low as 4 × 100 U. Some strains were negative for CDT activity in the cell lysate but positive in the culture supernatant. There was no strict correlation between the CDT activity in the culture supernatant and that in the cell lysate. To confirm that the observed cytodistending activity was due to intoxication by CDT, neutralizing assays using anti-CDT serum were performed. Since a previous study (32) demonstrated that anti-CDTC antiserum successfully neutralized the CDT activity of A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4, we used anti-CDTC serum in this assay. Of the 45 strains tested, the cytodistending activity of 40 strains was completely blocked by coincubation of a 100-fold dilution of anti-CDTC serum as shown in Fig. 1. On the other hand, the cell lysate of strains 2, 6, 8, 9, and 67 were weakly neutralized by the antiserum.

FIG. 1.

Cytodistending activity and genetic polymorphism of the cdt locus in A. actinomycetemcomitans clinical isolates. Culture supernatant and ultrasonic fractions from 45 clinical A. actinomycetemcomitans strains were assayed for cytodistending activity against HeLa cells. Cytodistending activity was estimated as the 50% cytotoxic dose, which was titrated as the end point of the highest twofold dilution of the sample showing 50% cytodistending cells after 72 h of incubation, and 1 U of CDT activity was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution. Open bars represent culture supernatants, and closed bars represent sonic lysates of which total proteins were adjusted to 1 mg/ml and added to HeLa cell culture. HindIII RFLP typing is from Fig. 3. Type VII consists of the strains which have no cdt genes. The presence (+) or absence (−) of the cdtB and cdtABC genes was determined by PCR with degenerative primers and the QIA-U and QIC-L primers, respectively. The inhibitory effect of anti-CDTC serum against cytodistension was determined (+, inhibited; +/−, no apparent effect). A.a, A. actinomycetemcomitans.

PCR studies.

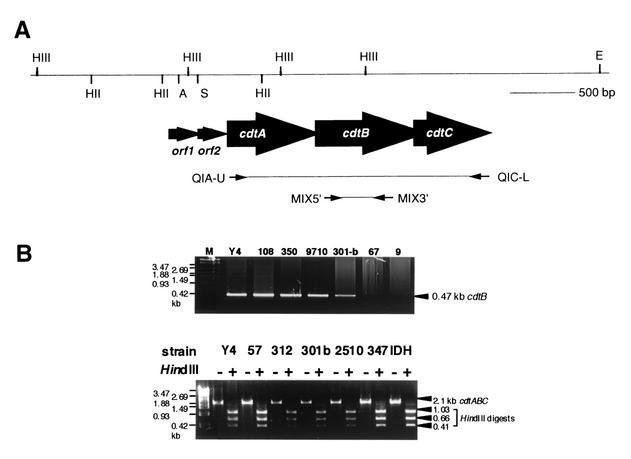

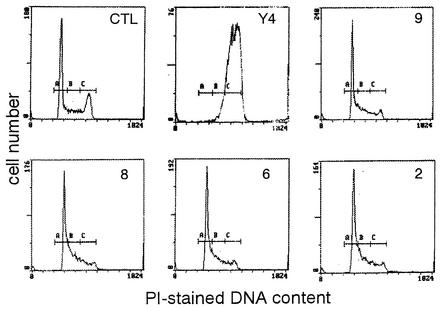

We initially investigated whether the degenerative oligonucleotide primers MIX5′ and MiX3′ (Fig. 2A; Table 1), designed based on various regions of the Escherichia coli and Campylobacter cdtB genes, which have been successfully used for the identification and cloning of cdtABC genes from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4, would produce an appropriate PCR product when DNA from the test strains was used as the template. A single product of the expected size (ca. 470 bp) was observed in 40 of the 45 A. actinomycetemcomitans strains tested (Fig. 2B). This size is very close to the expected size for a product amplified from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 cdtB by these degenerative primers. Sequencing and hybridization studies have confirmed that the 475-bp product from those A. actinomycetemcomitans strains does represent an amplified PCR product of the appropriate portion of the A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 cdtB. On the other hand, the rest of the tested strains yielded no PCR products at all. Next, the primers QIA-U and QIC-L were tested for their ability to amplify a DNA fragment containing the whole cdtABC genomic region in all A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. A single product of the expected size of 2.1 kb was amplified in 40 strains (Fig. 2B). The 2.1-kb PCR products from the 40 strains were cut with HindIII, yielding 0.41-, 0.66-, and 1.03-kb fragments, respectively; these sizes are in good agreement with those expected from restricted DNA fragments of the PCR product of A. actinomycetemcomitans. Since strains 9, 8, 6, 2, and 67 showed little cytodistending activity and gave no PCR products with either the cdtB degenerative or cdtABC primer sets, we also tried to observe a cell cycle G2/M block, which represented the unique feature of CDT, in these strains. As shown in Fig. 3, the culture supernatant from Y4 completely blocked the cell cycle at G2/M; however, those from strains 9, 8, 6, 2, and 67 did not show any activity.

FIG. 2.

Detection of cdtABC gene in A. actinomycetemcomitans clinical isolates. Panel A shows the genetic map of the A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 cdt locus. Restriction enzyme sites were shown on the cdt locus which contains the orf1, orf2, cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes. Primers used in this study are indicated by arrows. Panel B shows PCR amplification of the cdt genes. The top panel is a representative PCR amplification of the partial cdtB gene with the degenerative primer set Mix5′ and Mix3′. The bottom panel shows 2.1-kb PCR products with the primer set QIA-U and QIC-L. The results from HindIII digests indicate that the 2.1-kb PCR fragment is an amplicon from A. actinomycetemcomitans cdt genes. Restriction sites are indicated as follows: A, AccI; E, EcoRI; HIII, HindIII; HII, HincII; S, SmaI. +, present, −, absent.

FIG. 3.

Effect of A. actinomycetemcomitans culture supernatant on cell cycle pattern of HeLa cells. HeLa cells were incubated with sterile culture supernatants of the indicated strains for 24 h. CTL, control cells without treatment. The G2/M block was detected by staining cells with propidium iodide (PI) and using flow cytometry. A, B, and C represent the G1, S, and G2/M populations, respectively.

Taken together, 89% of A. actinomycetemcomitans clinical strains possessed the whole cdtABC gene and cytodistending activity, suggesting that the cdt locus was well conserved in A. actinomycetemcomitans.

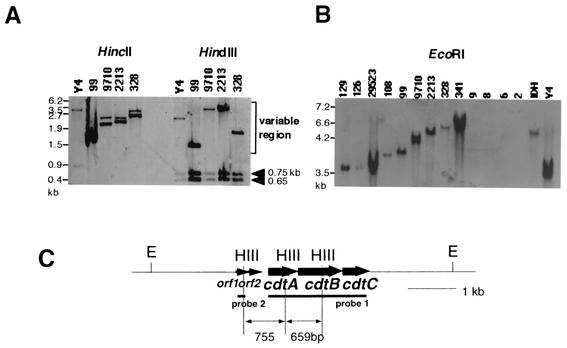

Analysis of cdt locus

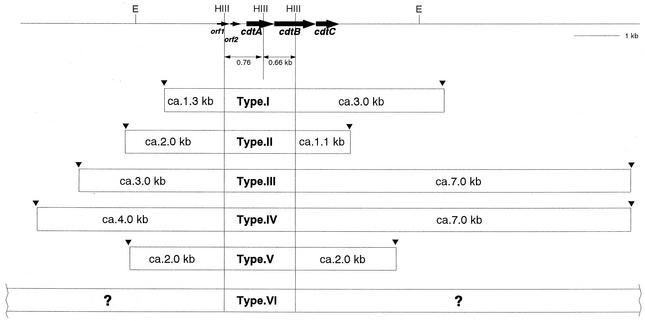

We next used an A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 PCR product corresponding to the entire region of the cdtABC genes in hybridizations with DNAs from the A. actinomycetemcomitans strains. Southern hybridization studies of HincII-, HindIII-, or EcoRI-digested chromosomal DNA of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains demonstrated that there were variations in the length of the hybridized fragments as shown in Fig. 4A and B. To establish the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) of flanking regions of the cdt genes, HindIII chromosomal digests were used. Probe 1 was used to study the polymorphism of the locus downstream of the cdt genes because we already knew that all A. actinomyctemcomitans strains, except strains 9, 8, 6, 2, and 67, conserved two HindIII sites in the cdt genes by PCR amplification as described above. As shown in Fig. 4A, three fragments of HindIII-digested genomic DNA were positive with probe 1 in each strain. Two bands were of 0.65 and 0.75 kb which corresponded to conserved regions inside the cdtABC genes. Another band showed a variation in the length from 1.1 to 7 kb. The RFLPs detected in the 3′ region of the cdtABC genes were classified into 5 types. In a group shown as type VI in Fig. 4, probe 1 hybridized with a very-high-molecular-weight DNA. Next, probe 2 was used to detect RFLPs upstream of the cdt genes. This probe 2 hybridized with DNA fragments of either 1.3, 2, 3, or 4 kb in length. It revealed 4 types of RFLP in the 5′ region. In the group type VI, probe 2 hybridized with a high-molecular-weight DNA fragment. Taken together, the results of both RFLP detections in the 5′ and 3′ region classify 41 A. actinomycetemcomitans strains into 6 types of HindIII RFLPs as shown in Fig. 5. The results of the HincII and EcoRI RFLP study supported these variations of 6 types of HindIII polymorphism (Fig. 4A and B). Southern hybridization also confirmed that strains 67, 9, 8, 6, and 2 did not possess the cdtABC genes shown in Fig. 4B, and these strains are grouped as type VII.

FIG. 4.

RFLP of the cdt locus. A 2.1-kbp PCR product from A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 was used for the Southern hybridization as probe 1. Another probe (probe 2) was prepared by PCR with orf1-specific primers annealed to the starting site of orf1 and the site just upstream of the HindIII site at the 3′ region of orf1. Southern hybridization of genomic DNA from various A. actinomycetemcomitans strains was performed with the cdtABC gene (probe 1) or orf1 gene (probe 2). Representative results with probe 1 are shown in panels A (HincII and HindIII [HIII] digests) and B (EcoRI [E] digests). Panel C shows a restriction map of the A. actinomycetemcomitans Y4 cdt gene locus.

FIG. 5.

Summary of HindIII RFLP of the A. actinomycetemcomitans cdt locus. E, EcoRI; HIII, HindIII.

DISCUSSION

Among the tested periodontopathogenic bacterial strains, only A. actinomycetemcomitans strains were almost ubiquitously found to produce strong CDT activity and be positive by PCR analysis for the cdt region. These results strongly suggest that CDT is a unique cytotoxin produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans species among periodontopathogenic bacteria, although a possibility remains that other periodontopathogenic bacteria produce other types of CDT which cannot be detected under our experimental conditions. A. actinomycetemcomitans possesses unique features in several points distinct from other periodontopathogens. A. actinomycetemcomitans is a facultative anaerobe while most of the other periodontopathogenic bacteria are obligate anaerobes (30, 34). A. actinomycetemcomitans produces at least two types of cytotoxin, leukotoxin and now CDT, while most of the other periodontopathogenic bacteria produce no such strong cytotoxic proteins (8, 14). Furthermore, A. actinomycetemcomitans has long been reported to produce immunosuppressing factor(s) (17, 19, 27, 29), and the recent study suggested that CDT might be one of the candidates. A. actinomycetemcomitans has been implicated as a major etiological agent in localized juvenile periodontitis and a key pathogen for some rapidly progressing and severe forms of adult periodontitis. Whether CDT production is involved in the pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans and causes such periodontal diseases remains to be explored.

As summarized in Fig. 1, titers of the CDT activity of A. actinomycetemcomitans varied among strains. There were not many differences in cell number and total protein in the preparations of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains and in the growth rate of the strains. Therefore, this variation in CDT activity is not due to differences in the conditions of preparation. Mayer et al. grouped A. actinomycetemcomitans strains by RFLP of three consecutive HindIII fragments covering the entire cdtABC. Most of the RFLP was found in the 3′ HindIII fragment, and they reported that the RFLP group containing cdtABC produces active CDT, but the CDT activities varied among strains in different RFLP groups. In this study, we considered that the DNA region upstream of orf1 is important for cdtABC expression because orf1 and orf2 form an operon with cdtABC based on the results of the CDT assay of recombinant E. coli carrying a deletion of a series of DNA-containing cdt loci (data not shown). Therefore we grouped A. actinomycetemcomitans strains by RFLP of four consecutive HindIII fragments covering orf1,orf2, and cdtABC. Our results clearly indicated that significant RFLP was present not only downstream but upstream of the cdtABC region. Our results further suggest that secretion of CDT and its activity in culture supernatants may be related to the restriction typings of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains to a certain degree. HindIII RFLP type I, II, and IV groups showed medium cytodistending activities. The activities in types II and IV were higher than those in type I. On the other hand, the activities in types III, V, and VI varied from less than 102 to more than 107. However, types V and VI may tend to have higher cytodistending activities than other types. Very low cytodistending activities in type VII can be explained by a partial or complete loss of the cdtABC genes. Our results that 89% of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains possessed the cdt genes were in agreement with Ahmed et al.'s report that 86% of closely related A. actinomycetemcomitans possessed all three cdt genes (1). In Campylobacter spp., 94% of 70 Campylobacter jejuni strains had mean titers of CDT activities but none of 35 Campylobacter coli strains appeared to produce active CDT (6, 7). Bang et al. (3) reported that all 101 isolates of C. jejuni, except one strain, had the cdt genes which were detected by PCR. In the case of Haemophilus ducreyi, 83% of 29 isolates from patients with chancroid expressed CDT activity and contained all of the cdtABC genes (1). This evidence suggests that the cdt genes commonly exist in these bacteria.

We previously reported that open reading frame 1 (ORF1), located just upstream of the cdtA gene, has homology with the VagC, VapB, and STBORF1 proteins, which play a role, respectively, in the stability of virulence plasmids in Dichelobacter nodosus, Salmonella enterica serovar Dublin, and Shigella flexneri (32). Genetic analysis of the cdt genes also revealed that a small stretch just downstream of the cdtC gene was homologous to an integrating plasmid of Haemophilus influenzae. Mayer et al. (18) analyzed the genetic orientation of the cdt flanking region and found that the cdt genes were flanked by an ORF of a virulence plasmid protein, a partial ORF of an integrase, and the DNA sequence of a bacteriophage integration site. This data suggest that A. actinomycetemcomitans acquired the cdt genes from other bacterial strains by means of a plasmid transfer or a bacteriophage infection. The reason why A. actinomycetemcomitans clinical isolates show variable RFLP types is not really known. Although there is no strict correlation between RFLP types and cytodistending activity in the culture supernatant of each strain, there is a considerable variation in cytodistending activity between strains belonging to types III to VI. Further analysis of the cdt locus-flanking regions in these strains may give a clue to the understanding of the variation of cytodistending activity in these strains.

In conclusion, we studied the prevalence of the cdt genes and CDT activities in various periodontopathogenic strains and demonstrated that most of A. actinomycetemcomitans strains possess the cdt genes and produce CDT activity. Our data suggest that CDT could be a potential virulence factor involved in the pathogenesis of A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontal diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Neil Ledger for editorial assistance. We thank the Research Facilities, Hiroshima University School of Dentistry and School of Medicine, for the use of their facilities.

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, and by the SATAKE research fund for young investigators society for the support of Hiroshima University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, H. J., L. A. Svensson, L. D. Cope, J. L. Latimer, E. J. Hansen, K. Ahlman, J. Bayat-Turk, D. Klamer, and T. Lagergard. 2001. Prevalence of cdtABC genes encoding cytolethal distending toxin among Haemophilus ducreyi and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:860-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baehni, P., C.-C. Tsai, W. P. McArthur, B. F. Hammond, and N. S. Taichman. 1979. Interaction of inflammatory cells and oral microorganisms. VIII. Detection of leukotoxic activity of a plaque-derived gram-negative microorganism. Infect. Immun. 24:233-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang, D. D., F. Scheutz, P. Ahrens, K. Pedersen, J. Blom, and M. Madsen. 2001. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin (cdt) genes and CDT production in Campylobacter spp. isolated from Danish broilers. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:1087-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cope, L., S. Lumbley, J. L. Latimer, J. Klesney-Tait, M. K. Stevens, L. S. Johnson, M. Purven, J. R. S. Munson, T. Lagergard, J. D. Radolf, and E. J. Hansen. 1997. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:4056-4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Rycke, J., and E. Oswald. 2001. Cytolethal distending toxin (CDT): a bacterial weapon to control host cell proliferation? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:141-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyigor, A., K. A. Dawson, B. E. Langlois, and C. L. Pickett. 1999. Cytolethal distending toxin genes in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates: detection and analysis by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1646-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eyigor, A., K. A. Dawson, B. E. Langlois, and C. L. Pickett. 1999. Detection of cytolethal distending toxin activity and cdt genes in Campylobacter spp. isolated from chicken carcasses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1501-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fives-Taylor, P., D. Meyer, K. Minz, and C. Brissette. 1999. Virulence factors of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Periodontol. 2000. 20:136-167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Helgeland, K., and O. Nordby. 1993. Cell cycle-specific growth inhibitory effect on human gingival fibroblasts of a toxin isolated from the culture medium of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontol. Res. 28:161-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamen, P. R. 1983. Inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation by extracts of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 42:1191-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamin, S., W. Harvey, M. Wilson, and A. Scutt. 1986. Inhibition of fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis by capsular material from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Med. Microbiol. 22:245-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataoka, M., K. Kawamura, T. Kondoh, Y. Wakano, and H. Ishida. 1993. Purification of a fibroblast-inhibitory factor from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans Y4. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 107:111-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiley, P., and S. C. Holt. 1980. Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans Y4 and N27. Infect. Immun. 30:862-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolodrubetz, D., T. Dailey, J. Ebersole, and E. Kraig. 1996. Molecular genetics and the analysis of leukotoxin in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontol. 67:309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lally, E. T., and I. R. Kieba. 1994. Molecular biology of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin, p. 69-82. In R. Genco, S. Hamada, T. Lehner, J. McGhee, and S. Mergenhagen (ed.), Molecular pathogenesis of periodontal disease. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Lally, E. T., I. R. Kieba, E. E. Golub, J. D. Lear, and J. C. Tanaka. 1996. Structure/function aspects of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin. J. Periodontol. 67:298-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangan, D., N. S. Taichman, E. T. Lally, and S. M. Wahl. 1991. Lethal effect of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin on human T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 59:3267-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer, M. P., L. C. Bueno, E. J. Hansen, and J. M. DiRienzo. 1999. Identification of a cytolethal distending toxin gene locus and features of a virulence-associated region in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 67:1227-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meghji, S., M. Wilson, B. Henderson, and D. Kinane. 1992. Anti-proliferative and cytotoxic activity of surface-associated material from periodontopathogenic bacteria. Arch. Oral Biol. 8:637-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuda, J., H. Kurazono, and Y. Takeda. 1995. Distribution of the cytolethal distending toxin A gene (cdtA) among species of Shigella and Vibrio, and cloning and sequencing of the cdt gene from Shigella dysenteriae. Microb. Pathog. 18:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peres, S. Y., O. Marches, F. Daigle, J.-P. Nougayrede, F. Herault, C. Tasca, J. De Rycke, and E. Oswald. 1997. A new cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) from Escherichia coli producing CNF2 blocks HeLa cell division in G2/M phase. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1095-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickett, C. L., D. L. Cottle, E. C. Pesci, and G. Bikah. 1994. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin genes. Infect. Immun. 62:1046-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickett, C. L., E. C. Pesci, D. L. Cottle, G. Russell, A. N. Erdem, and H. Zeytin. 1996. Prevalence of cytolethal distending toxin production in Campylobacter jejuni and relatedness of Campylobacter sp. cdtB genes. Infect. Immun. 64:2070-2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson, P. M., M. Lantz, P. T. Marucha, K. S. Kornman, C. L. Trummel, and S. C. Holt. 1982. Collagenolytic activity associated with Bacteroides spp. and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J. Periodontol. Res. 17:275-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saglie, F. R., K. Simon, J. Merrill, and H. P. Koeffler. 1990. Lipopolysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans stimulates macrophages to produce interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor mRNA and protein. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 5:256-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott, D. A., and J. B. Kaper. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of the genes encoding Escherichia coli cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 62:244-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenker, B., M. E. Kushner, and C.-C. Tsai. 1982. Inhibition of fibroblast proliferation by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 38:986-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shenker, B. J., T. McKay, S. Datar, M. Miller, R. Chowhan, and D. Demuth. 1999. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans immunosuppressive protein is a member of the family of cytolethal distending toxins capable of causing a G2 arrest in human T cells. J. Immunol. 162:4773-4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenker, B. J., L. A. Vitale, and D. A. Welham. 1990. Immune suppression induced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: effects on immunoglobulin production by human B cells. Infect. Immun. 58:3856-3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slots, J., H. S. Reynolds, and R. J. Genco. 1980. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: a cross-sectional microbiological investigation. Infect. Immun. 29:1013-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens, R. H., C. Gatewood, and B. F. Hammond. 1983. Cytotoxicity of the bacterium Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans extracts in human gingival fibroblasts. Arch. Oral Biol. 28:981-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugai, M., T. Kawamoto, S. Y. Peres, Y. Ueno, H. Komatsuzawa, T. Fujiwara, H. Kurihara, H. Suginaka, and E. Oswald. 1998. The cell cycle-specific growth-inhibitory factor produced by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a cytolethal distending toxin. Infect. Immun. 66:5008-5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Dyke, T. E., E. Bartholomew, R. J. Genco, J. Slots, and M. J. Levine. 1982. Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by soluble bacterial products. J. Periodontol. 53:502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zambon, J. J. 1994. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in adult periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 65:892-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]