Abstract

The isotope enrichment factors (ɛ) in Methanosaeta concilii and in a lake sediment, where acetate was consumed only by Methanosaeta spp., were clearly less negative than the ɛ usually observed for Methanosarcina spp. The fraction of methane produced from acetate in the sediment, as determined by using stable isotope signatures, was 10 to 15% lower when the appropriate ɛ of Methanosaeta spp. was used.

Methane is a major product of the degradation of organic matter in anoxic environments like rice paddies, natural wetlands, and lake sediments. Its production from H2-CO2 and acetate (ac) in natural systems has been quantified by stable isotope modeling (7, 17). One of the input parameters needed is the carbon isotope fractionation of acetoclastic methanogenesis. To determine the fractionation factor (α) in culture or in an environmental system, the δ13C of the methyl carbon of acetate (ac-methyl) must be known, since CH4 is produced from the methyl carbon rather than the carboxyl carbon of acetate (5, 19). For Methanosarcina spp. isotope fractionation has been determined in pure culture (7, 10, 20) and has been verified in natural environments dominated by this group of acetoclastic methanogens (14). However, detailed data on isotope fractionation by Methanosaeta spp. are rare. Valentine et al. (18) reported a rather low fractionation factor (α = 1.007) for thermophilic Methanosaeta thermophila. Similarly, the fractionation factor for mesophilic Methanosaeta concilii also seems to be lower (α = 1.017) (A. Chidthaisong, S. C. Tyler, et al., unpublished results) than that for Methanosarcina spp. (α = 1.021 to 1.027) (for a review see reference 18). A difference in isotope fractionation by the two acetoclastic methanogenic groups is possible, since they differ in their biochemical activation of acetate to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA).

To increase our knowledge of isotope fractionation by Methanosaeta spp., we grew M. concilii under defined conditions and determined the isotope enrichment factor (ɛ). We also determined isotope fractionation by acetoclastic Methanosaeta spp. in a natural environment, Lake Dagow sediment, in which only members of the Methanosaetaceae were detected (2, 8).

Cultures (n = 5) of M. concilii DSM 3671 were grown under N2-CO2 (80:20) at 37°C in glass bottles (250 ml; Müller Krempel, Bülach, Switzerland) without shaking using carbonate-buffered (pH 7.1) mineral medium (DSM medium 334). Sodium acetate was added to an initial concentration of approximately 70 mM. For the total molecule the added acetate (ac) had a δ13Cac of −24.0‰, and for the methyl group the δ13Cac-methyl was −29.4‰. After inoculation with a 20% bacterial suspension in the late exponential phase (resulting in a final volume of 125 ml), several gas (0.4-ml) and liquid (2-ml) samples were removed and used for analysis of pH, concentration, and the carbon isotope composition of acetate and the products formed.

Sediment samples from eutrophic Lake Dagow (Northern Brandenburg, Germany) were obtained on 9 November 2004 and 17 August 2005 and transported to the laboratory in Marburg as described previously (8). The sediment samples from 2004 (19 ml; depth, 0 to 10 cm) and from 2005 (10 ml; depth, 0 to 5 cm) were placed in 120-ml serum vials and 27-ml pressure tubes, respectively. The glass vessels were closed with butyl rubber stoppers and incubated under an N2 atmosphere at 10°C without shaking. After preincubation overnight, the appropriate volume of a sodium acetate stock solution (40.6 mM) was added to obtain an initial acetate concentration of 1 mM. The acetate had a δ13Cac of −32.1‰ and a δ13Cac-methyl of −36.4‰. At each time examined during incubation triplicate tubes were analyzed and subsequently sacrificed. In another experiment, using sediment from 2005, CH4 production was investigated after consumption of the acetate that was added. To do this, the headspace was exchanged with N2, which was followed by repeated gas sampling over the next 18 days.

Chemical and isotopic analyses were performed as described by Penning and Conrad (13). A stable isotope analysis of 13C/12C in gas samples was performed using a gas chromatograph-combustion-isotope ratio mass spectrometer system (Thermoquest, Bremen, Germany) (13). Measurement of isotopes and quantification of acetate were performed with a high-performance liquid chromatography system coupled to Finnigan LC IsoLink (Thermo Electron Corporation, Bremen, Germany). Off-line pyrolysis was performed to determine δ13Cac-methyl contents (1, 3).

The amount of total inorganic carbon (TIC) produced by M. concilii was calculated (13) and was expressed as the difference between the amount of TIC at any time and the initial amount of TIC. The isotope enrichment factor associated with acetoclastic methanogenesis was determined as described by Mariotti et al. (11) from the residual reactant

|

(1) |

and from the product formed

|

(2) |

where δri is the isotope composition of the reactant (either ac or ac-methyl) at the beginning, δr and δp are the isotope compositions of the residual ac and the pooled CH4, respectively, at the instant when f was determined, and f is fractional yield of the products based on the consumption of ac (0 < f < 1). Linear regression of δr against ln(1 − f) and of δp against (1 − f)[ln(1 − f)]/f gives ɛ as the slope. The enrichment factor was converted to the fractionation factor: ɛ = 103 × (1 − α).

The relative contribution of acetate- and CO2-derived CH4 to total CH4 was determined as follows (4):

|

(3) |

where fmc is the fraction of CH4 formed from H2-CO2, δma and δmc are the isotope ratios of CH4 derived from either ac or H2-CO2, and δCH4-new is the isotopic signature calculated for the methane formed since the last measurement (13). δma was calculated from δac-methyl using αma (experimentally determined in this study and from previously published data). δmc was calculated using the isotope fractionation factor for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (αCO2/CH4 = 1.085) determined previously for Lake Dagow sediment (2). For calculation of δma, δac-methyl was assumed to be equal to δ13C of organic matter (δorg = −30.4 ± 0.4) (2).

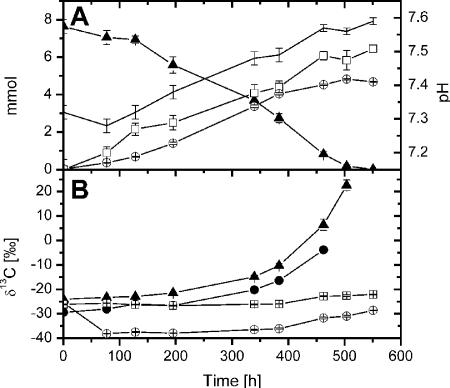

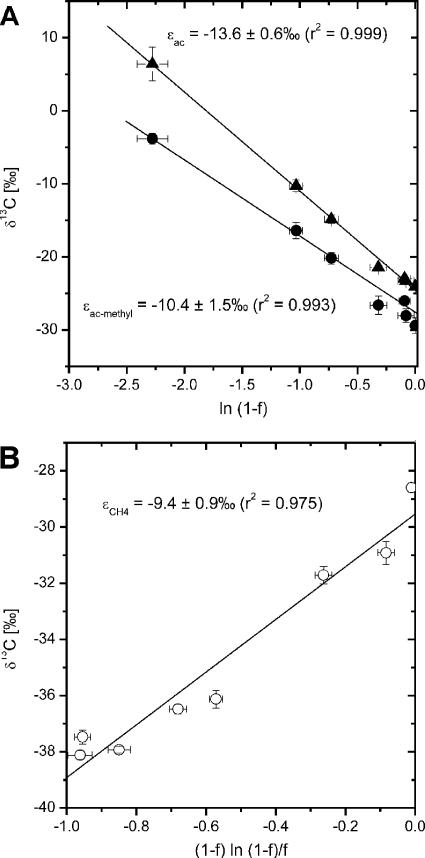

During growth experiments with M. concilii acetate was consumed within 550 h to threshold concentrations and was converted to CO2 and CH4 (Fig. 1A). The amount of CO2 and CH4 accounted for approximately 73% of the initial amount of acetate. As expected for a closed-system approach, the δ13C values for both the substrate and the products increased due to continuous preferential consumption of the [12C]acetate (Fig. 1B). The initial high δ13C value of methane (δ13CCH4) was due to transfer of dissolved CH4 by inoculation. δ13CCO2 increased with time but was not used for determination of isotope fractionation, since the high background level of the bicarbonate buffer did not allow precise quantification of the δ13C of the newly formed TIC. Isotope fractionation during CH4 formation from acetate was determined from data for acetate, ac-methyl, and CH4 using equations 1 and 2 (Fig. 2). The isotope enrichment factors determined for ac-methyl (ɛac-methyl = −10.4‰ ± 1.5‰) and CH4 (ɛCH4 = −9.4‰ ± 0.9‰) agreed within error, whereas the isotope enrichment factor for acetate (both carbon atoms) was more negative (ɛac = −13.6‰ ± 0.6‰). The good correlation fit indicates that even for a wide range of concentrations (70 mM to the threshold concentration) the magnitude of isotope fractionation was basically unchanged. Isotope enrichment in the carboxyl carbon of ac (ac-carboxyl) was calculated from δ13Cac-carboxyl (δ13Cac-carboxyl = 2δ13Cac − δ13Cac-methyl) using equation 1, resulting in an ɛac-carboxyl value of −16.0‰.

FIG. 1.

Catabolism of acetate in a pure culture of M. concilii. (A) Acetate consumption, product formation, and pH. (B) Isotope signatures of total acetate, ac-methyl, CO2, and CH4. ▴, ac; •, ac-methyl; □, CO2; ○, CH4; line with no symbols, pH. The values are means ± standard errors (n = 5).

FIG. 2.

Isotope enrichment during acetoclastic methanogenesis by M. concilii. The plots are based on equations derived by Mariotti et al. (11). (A) ▴, ac; •, ac-methyl. (B) CH4. The values are means ± standard errors (n = 5).

Our study shows that the isotopic fractionation factor of acetate methyl to CH4 was much less in M. concilii (ɛ = ∼−10‰) than in Methanosarcina barkeri (ɛ = ∼−20‰) (7). The agreement of isotope enrichment in ac-methyl (ɛac-methyl) (Fig. 2A) and CH4 (ɛCH4) (Fig. 2B) is a reasonable result, since in M. concilii the methyl group should be almost exclusively (98%) used for methane production (12). After complete consumption of acetate, the intercept of the regression line of CH4 (δri) (Fig. 2B) was −29.5‰, which is almost identical to δ13Cac-methyl (−29.4‰), as expected from equation 2. The δ13C of the biomass of M. concilii was not determined in the experiment reported here, but previous studies showed that the biomass was slightly 13C enriched with respect to the initial δ13Cac (ɛbiomass = 6.0‰ ± 0.7‰) (unpublished data). We assumed that due to the relatively low level of biomass formation in anaerobic metabolism δ13CCH4 was probably not significantly affected, but this might have resulted in slightly enhanced depletion of 13C in the catabolic product CH4 (e.g., a lower ɛ for CH4 than for ac and ac-methyl).

The depletion of 13C in the ac-carboxyl (ɛac-carboxyl = −16.0‰) was greater than that in the ac-methyl, as observed previously for M. barkeri (7). The stronger fractionation in ac-carboxyl could theoretically have been caused by reversible exchange of the carbonyl carbon of acetyl-CoA with the 13C-enriched CO2 in the growth medium. This exchange reaction was observed in M. barkeri (6). However, when we considered such an exchange reaction using a δ13Cac-carboxyl value of −18.7‰ of the initial acetate and a δ13CCO2 value of ≤−24‰ (Fig. 1B), we expected 13C depletion leading to weaker isotope fractionation in δ13Cac-carboxyl, which was not the case. Therefore, the exchange reaction either might not be active in M. concilii or might be catalyzed to only a minor extent. As an alternative explanation we suggest that the stronger isotope fractionation in the ac-carboxyl was caused by 13C fractionation during conversion of acetate via acetyl phosphate to acetyl-CoA. The actual bond breaking of this reaction occurs at the carboxyl carbon (5), and therefore the carboxyl carbon might experience a stronger isotope effect.

The isotope fractionation during acetoclastic methanogenesis in Methanosaeta spp. (M. concilii in this study and M. thermophila in the study of Valentine et al. [18]) is apparently weaker than that in Methanosarcina spp., in which fractionation factors typically range from 1.021 to 1.027, equivalent to enrichment factors of −21 to −27‰ (7, 10, 20). Gelwicks et al. (7) proposed that the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) enzyme complex catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the overall reaction and therefore is responsible for the observed fractionation. Yet this does not explain the difference in isotope fractionation caused by the two groups of acetoclastic methanogenic archaea. Although the CODHs of Methanosarcina spp. and Methanosaeta spp. differ to some extent, the enzymes catalyze the same principal reactions, which determine the magnitude of the isotope effect. Thus, a priori it is not expected that the two CODHs would exhibit very different isotope effects. We therefore speculated that the difference in the overall isotope fractionation is caused by the initial activation of acetate. In this reaction the two acetoclastic genera differ biochemically. While Methanosarcina spp. activate acetate in two steps (acetate kinase and phosphotransacetylase) at the expense of one high-energy phosphate bond, Methanosaeta spp. activate acetate using the acetyl-CoA synthetase at the expense of two high-energy phosphate bonds (9). Activation by Methanosarcina spp., which is driven only by the energy from the breakage of one high-energy bond, may have greater reversibility. This could explain why the isotope effect of the later C—C bond cleavage of acetyl-CoA is expressed more strongly.

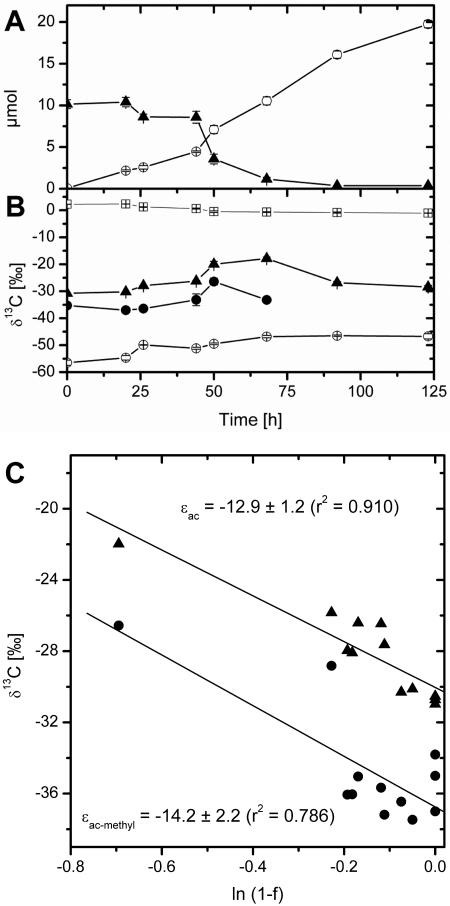

Lake Dagow sediment (obtained in 2004) was incubated anoxically after addition of acetate (initial concentration, 1 mM). Under these conditions CH4 was produced from H2-CO2, from acetate that is naturally produced in the sediment, and from the acetate added (Fig. 3A). Within 92 h, the elevated concentrations caused by addition of acetate decreased to constant low concentrations (93 ± 18 μM). Quantification of acetate and CH4 showed that in the sediment samples 52% of the total CH4 produced was derived from the additional acetate. Note that acetoclastic methanogenesis was the only acetate-consuming process in the sediment, which was devoid of sulfate or other inorganic electron acceptors (2). Due to preferential consumption of 12C for CH4 production, ac, as well as ac-methyl, became enriched in 13C with time (Fig. 3B). Simultaneously, CH4 also became isotopically enriched, but to a minor extent. After 50 h, δ13C again decreased due to dilution of the residual 13C-enriched acetate by acetate produced from anaerobic degradation of sediment organic matter. Since CH4 was also produced from H2-CO2, isotope enrichment by acetoclastic methanogenesis was calculated only from the isotope data for acetate. Only data for f values that were ≥0 and ≤0.5 (ln[1 − f] ≥ −0.7) were analyzed, since acetate was still being produced in the sediment. At a higher f value the continuously produced isotopically relatively light acetate would dilute δ13Cac-methyl and δ13Cac (Fig. 3) and therefore bias the quantification of ɛ. The values of ɛac and ɛac-methyl determined were −12.9‰ ± 1.2‰ and −14.2‰ ± 2.2‰, respectively. The data point at a ln(1 − f) value of 0.69 influenced the determination of ɛ. Removal of this data point altered ɛac to −20.3‰, yet ɛac-methyl changed only slightly to −11.6‰. We also studied sediment obtained in 2005. Although the ɛ values determined were somewhat different (ɛac = −17.2‰ ± 1.2‰ with r2 = 0.928; ɛac-methyl = −7.8‰ ± 1.8‰ with r2 = 0.566), they clearly confirmed the tendency of ɛ to be greater than −20‰. Notably, the results for Lake Dagow sediment confirmed that the ɛ values for Methanosaeta spp. were clearly less than those for Methanosarcina spp. (7, 10, 20).

FIG. 3.

Acetate consumption in Lake Dagow sediment (obtained in 2004) amended with acetate. (A) Acetate consumption (▴) and CH4 production (○). (B) Isotope ratios of total ac (▴), ac-methyl (•), CO2 (□), and CH4 (○). (C) The plots are based on equations derived by Mariotti et al. (11). The values in panels A and B are means ± standard errors (n = 3).

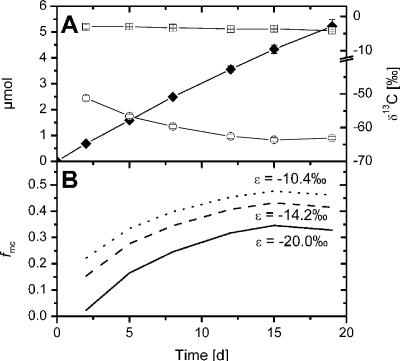

The difference between the two acetoclastic methanogenic genera is important for correct computation of the amount of CH4 that is produced from acetate compared with the amount of CH4 that is produced from CO2 (equation 3). A lower ɛac-methyl value leads to a higher value of fmc. Thus, application of the fractionation factor of Methanosarcina spp. to an environment that is dominated by Methanosaeta spp. would result in underestimation of the relative contribution of H2-CO2-dependent CH4 production. We tested the influence of ɛac-methyl on this quantification using data from anoxic incubation of Lake Dagow sediment. We used sediment samples from 2005 and calculated the relative fraction of CH4 produced from H2-CO2 (fmc) (equation 3) during the incubation while CH4 was produced at a constant rate (Fig. 4A). δ13CCO2 in the carbonate-buffered system stayed fairly constant, while δ13CCH4 decreased, reaching stabile values around −63‰. The sensitivity of fmc to ɛac-methyl was calculated using the enrichment factors either for Methanosarcina spp. (7), for M. concilii (Fig. 2A), or for Lake Dagow sediment (Fig. 4B). Comparison of calculated fmc values showed that fmc was on average larger by 0.11 units (ɛac-methyl = −14.2‰) and 0.15 units (ɛac-methyl = −10.4‰) using enrichment factors obtained in this study rather than using previously published values typical for acetoclastic Methanosarcina spp. (ɛac-methyl = −20‰). The final fmc values were 0.33, 0.42, and 0.46 for ɛac-methyl values of −20‰, −14.2‰, and −10.4‰, respectively. The fmc values of 0.2 to 0.3 calculated for an previous incubation experiment performed with Lake Dagow sediment (2) might have been biased by such an inappropriate fractionation factor, so that the real values probably are slightly higher (0.3 to 0.4), as suggested by Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Effect of ɛac-methyl on quantification of the fraction of CH4 originating from H2-CO2 (fmc). (A) Production of CH4 (⧫) and isotope ratios of the newly formed CH4 (○) and of the CO2 (□) during incubation of Lake Dagow sediment (obtained in 2005). The values are means ± standard errors (n = 3). (B) fmc calculated using different enrichment factors (ɛac-methyl) (an ɛac-methyl of −14.2‰ is the value determined in this study for Lake Dagow sediment).

Our results show that two functionally equivalent groups of acetoclastic methanogens, whose biochemical pathways differ, exhibit different isotope fractionation and consequently affect isotope modeling. Hence, microbial community structure can affect biogeochemical fluxes and thus provides an example of the hypothesis that the composition of environmental microbial communities does affect ecosystem function (15, 16).

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blair, N., A. Leu, E. Munoz, J. Olsen, E. Kwong, and D. DesMarais. 1985. Carbon isotopic fractionation in heterotrophic microbial metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:996-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan, O. C., P. Claus, P. Casper, A. Ulrich, T. Lueders, and R. Conrad. 2005. Vertical distribution of structure and function of the methanogenic archaeal community in Lake Dagow sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1139-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chidthaisong, A., K. J. Chin, D. L. Valentine, and S. C. Tyler. 2002. A comparison of isotope fractionation of carbon and hydrogen from paddy field rice roots and soil bacterial enrichments during CO2/H2 methanogenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66:983-995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conrad, R. 2005. Quantification of methanogenic pathways using stable carbon isotopic signatures: a review and a proposal. Org. Geochem. 36:739-752. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferry, J. G. 1992. Methane from acetate. J. Bacteriol. 174:5489-5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer, R., and R. K. Thauer. 1990. Methanogenesis from acetate in cell extracts of Methanosarcina barkeri: isotope exchange between CO2 and the carbonyl group of acetyl-CoA, and the role of H2. Arch. Microbiol. 153:156-162. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelwicks, J. T., J. B. Risatti, and J. M. Hayes. 1994. Carbon isotope effects associated with aceticlastic methanogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:467-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glissmann, K., K. J. Chin, P. Casper, and R. Conrad. 2004. Methanogenic pathway and archaeal community structure in the sediment of eutrophic Lake Dagow: effect of temperature. Microb. Ecol. 48:389-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jetten, M. S. M., A. J. M. Stams, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1990. Acetate threshold and acetate activating enzymes in methanogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 73:339-344. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krzycki, J. A., W. R. Kenealy, M. J. DeNiro, and J. G. Zeikus. 1987. Stable carbon isotope fractionation by Methanosarcina barkeri during methanogenesis from acetate, methanol, or carbon dioxide-hydrogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2597-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariotti, A., J. C. Germon, P. Hubert, P. Kaiser, R. Letolle, A. Tardieux, and P. Tardieux. 1981. Experimental determination of nitrogen kinetic isotope fractionation: some principles; illustration for the denitrification and nitrification processes. Plant Soil 62:413-430. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel, G. B. 1984. Characterization and nutritional properties of Methanothrix concilii sp. nov., a mesophilic, aceticlastic methanogen. Can. J. Microbiol. 30:1383-1396. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Penning, H., and R. Conrad. 2006. Carbon isotope effects associated with mixed acid fermentation of saccharides by Clostridium papyrosolvens. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70:2283-2297. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penning, H., S. C. Tyler, and R. Conrad. 2006. Determination of isotope fractionation factors and quantification of carbon flow by stable carbon isotope signatures in a methanogenic rice root model system. Geobiology 4:109-121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schimel, J. 1995. Ecosystem consequences of microbial diversity and community structure. Ecol. Stud. 113:239-254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schimel, J. P., and J. Gulledge. 1998. Microbial community structure and global trace gases. Global Change Biol. 4:745-758. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyler, S. C., R. S. Bilek, R. L. Sass, and F. M. Fisher. 1997. Methane oxidation and pathways of production in a Texas paddy field deduced from measurements of flux, d13C, and dD of CH4. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 11:323-348. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentine, D. L., A. Chidthaisong, A. Rice, W. S. Reeburgh, and S. C. Tyler. 2004. Carbon and hydrogen isotope fractionation by moderately thermophilic methanogens. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68:1571-1590. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weimer, P. J., and J. G. Zeikus. 1978. Acetate metabolism in Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch. Microbiol. 119:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zyakun, A. M., V. A. Bondar, K. S. Laurinavichus, O. V. Shipin, S. S. Belyaev, and M. V. Ivanov. 1988. Fractionation of carbon isotopes under the growth of methane-producing bacteria on various substrates. Mikrobiol. Zh. 50:16-22. [Google Scholar]