Abstract

Incidental blood agar-based recovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis led us to further investigate this routine medium for primary isolation and culture of M. tuberculosis. Fifteen respiratory tract and eight lymph node Ziehl-Neelsen-positive specimens were inoculated in parallel into tubes containing egg-based medium and 5% sheep blood agar. Colonies appeared sooner on this medium than on the egg-based medium, but this difference was not significant (P = 0.11, analysis of variance [ANOVA] test). Further experiments compared the growth of 38 respiratory and lymph node M. tuberculosis isolates when subcultured on the two media. After 6 days of incubation, 21 of 38 isolates had grown on blood agar, and the mean number of colonies was significantly greater on blood agar than on the egg-based medium (P < 0 0.001, ANOVA test). These results demonstrate that M. tuberculosis grows easily on blood agar within 1to 2 weeks, indicating that this basic medium is suitable for laboratory diagnosis of tuberculosis in addition to other media. Laboratories that routinely use prolonged incubations of blood plates, for example, for the recovery of Bartonella species, should consider the potential safety implications of encountering this highly infectious pathogen.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a slow-growing bacterium that is the etiological agent of tuberculosis. Agar-based and egg-based media incorporating green malachite and Middlebrook broths or solid media are recommended as the “gold standard” for isolation, culture, and definite diagnosis of M. tuberculosis (6). Although there has been one anecdotal report of the isolation of M. tuberculosis on blood agar (M. Arvand, M. E. Mielke, T. Weinke, T. Regnath, and H. Hahn, Letter, Infection 26:254, 1998), microbiologists and medical students have been taught for decades that isolation of the organism requires a defined, egg-based medium, such as Lowenstein-Jensen medium (6).When trying to isolate Bartonella henselae from a lymph node by prolonged incubation on blood agar (5), we were surprised to isolate M. tuberculosis instead. The purpose of this preliminary work was to evaluate whether blood agar and prolonged incubation could support the growth of a variety of strains of M. tuberculosis obtained from different specimens. We now report that the current basic blood agar medium, used widely for nearly all primary isolations of bacteria, is at least as efficient as the widely recommended Lowenstein Jensen medium.

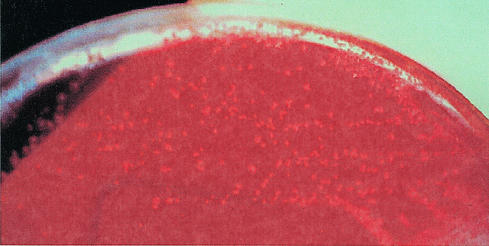

Twenty three Ziehl-Neelsen-positive samples (15 respiratory tract specimens and 8 lymph node aspirates) were inoculated in parallel into tubes containing egg-based Coletsos medium, a local enriched formulation of Lowenstein-Jensen medium (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and 5% sheep-blood agar (Bio Technologie Appliquée, Dinan, France). The respiratory tract specimens were digested using dithiothreitol and decontaminated using 2% NaOH before inoculation (6). Tubes were incubated at 37°C in a non-CO2 atmosphere for 30 days, and they were examined every 2 days for the presence of colonies. The time for appearance of colonies and the number of colonies were noted during the 30-day inoculation period. Identification of isolates was confirmed by acid-fast staining and 16S rRNA-probe hybridization (GenProbe, San Diego, Calif.). No contamination was observed after inoculation of these clinical specimens, and M. tuberculosis was recovered from all specimens on both media after a 30-day incubation period. Colonies were easily recognized as small, nonpigmented, and rough on blood agar (Fig. 1). Although the perception was that colonies appeared sooner on blood agar than on the egg-based Coletsos medium, differences in the time of detection and in the number of colonies were not significant (P = 0.11, analysis of variance test). Isolation was achieved after 1 week for specimens exhibiting more than 50 acid-fast bacilli per microscopic field and after 2 weeks for specimens exhibiting fewer than 1 acid-fast bacillus per microscopic field.

FIG. 1.

Colonies of M. tuberculosis on blood agar plates.

In further experiments we compared the growth of 38 respiratory and lymph node M. tuberculosis isolates on the two media. Ten microliters of a 106-mycobacteria/ml suspension of each isolate was streaked in parallel on egg-based and 5% sheep-blood agar in tubes and incubated at 37°C for 6 days before colonies were counted. After 6 days of incubation, 21 of 38 isolates had grown on egg-based agar and 27 of 38 isolates had grown on blood agar. The mean number of colonies on blood agar (1,049 ± 2,687) was significantly greater than on the egg-based medium (621 ± 2,256) (P < 0 0.001, analysis of variance test). Ten microliters of 106- to 103-CFU/ml serial 10-fold of dilutions of three respiratory isolates of M. tuberculosis were inoculated in parallel on the two media. After 6 days of incubation, growth was detected after plating 102 to 103 CFU regardless of the medium.

M. tuberculosis was first isolated by Robert Koch from freshly crushed pulmonary tubercles after 10 days of incubation using heat-coagulated sheep and beef serum medium in tubes (4). Isolates were also recovered by using blood agar (1), but this was superceded by an egg-based agar which, by the 1920s, became the standard recommended medium for primary isolation of M. tuberculosis because of the ease in sterilizing the egg-based medium (2). To our knowledge, no comparative study comparing the efficacy of blood-based agars and egg-based agars has been carried out, and even the ability of blood agar to support growth of M. tuberculosis was forgotten. In this report, we demonstrated that primary isolation of M. tuberculosis was achieved 10 to 15 days after of inoculation of clinical samples, and that subculture in the same medium was achieved within 6 days. Our results show that when desiccation is prevented by use of tubes instead of plates, blood agar is a suitable alternative for the primary isolation of M. tuberculosis and may even be superior to egg-based agar for subculture of the organism. Blood agar also facilitates the recovery of other fastidious, slow-growing organisms that may be present in addition to M. tuberculosis, such as Bartonella spp. (6). However, since blood agar is not a selective medium, it may be more suitable for noncontaminated specimens. Inoculation of blood agar could be done immediately in order to avoid a delay in shipping clinical specimens to reference laboratories with specialized media. Since prolonged incubation of blood agar has recently been advocated as a means of evaluating enlarged lymph node specimens (3), our observations suggest that laboratories could encounter M. tuberculosis in addition to Bartonella spp. and other fastidious pathogens. Consequently, appropriate microbiological safety measures should be in place to counter the highly infectious nature of M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge C. Fontaine for technical assistance, P. Nordmann for helpful discussion, and R. Birtles for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bezançon, F., and V. Griffon. 1903. Culture du bacille tuberculeux sur la pome de terre emprisonnée dans la gélose glycérinée et sur le sang gélosé. C. R. Soc. Biol. 51:77-79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezançon, F., and V. Griffon. 1903. Culture du bacille tuberculeux sur le “jaune d'oeuf gélosé.” C. R. Soc. Biol. 55:603-604. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolan, M. J., M. T. Wong, R. L. Regnery, and D. Drehner. 1992. Syndrome of Rochalimaea henselae adenitis suggesting cat scratch disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 118:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch, R. 1882. Die aetiologie der tuberculose. Berl. Klin. Wochenschr. 15:221-236.

- 5.La Scola, B., and D. Raoult. 1999. Culture of Bartonella quintana and Bartonella henselae from human samples: a 5-year experience (1993 to 1998). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1899-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metchock, B. G., F. S. Nolte, and R. J. Wallace. 1999. Mycobacterium, p. 399-437. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, C. F. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken. (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.