Abstract

The nasopharyngeal Haemophilus influenzae flora of healthy children under the age of 3 years attending day care centers in three distinct French geographic areas was analyzed by sampling during two periods, spring 1999 (May and June) and fall 1999 (November and December). The average carrier rate among 1,683 children was 40.9%. The prevalence of capsulated H. influenzae carriers was 0.4% for type f and 0.6% for type e. No type b strains were found among these children, of whom 98.5% had received one or more doses of anti-Haemophilus b vaccine. Among the strains, 44.5% were TEM-type beta-lactamase producers and nine (1.3%) were beta-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant strains. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis restriction patterns showed a large diversity with 366 SmaI patterns from 663 strains. Among the strains isolated during a given period, 33% were isolated simultaneously in more than one area. In each area, depending on the sampling period, 68 to 72% of the strains had new pulsotypes and persistence of 28 to 32% of the strains was noted. For the 297 beta-lactamase-producing strains, 194 patterns were found. The genomic diversity of these strains was comparable to that of the whole set of strains and does not suggest a clonal diffusion. Among the beta-lactamase-producing strains isolated in November and December, depending on the area, 66 to 73% had new pulsotypes with persistence of only 27 to 33% of the strains. In any given geographic area, colonization by H. influenzae appears to be a dynamic process involving a high degree of genomic heterogeneity among the noncapsulated colonizing strains.

Haemophilus influenzae is one of the main bacterial species causing infection in children. Encapsulated strains are responsible for a variety of invasive diseases, the most frequent being meningitis, but epiglottitis, arthritis, pneumonia, and cellulitis also occur (36). These invasive diseases have decreased sharply since the generalization of anti-Haemophilus b (anti-Hib) vaccination (22, 37). Noncapsulated strains frequently cause acute otitis media in children (6, 20, 29, 32). H. influenzae is often part of the nasopharynx flora and is frequently found in the upper respiratory tract of healthy children, with reported carriage rates of up to 60% (12, 17, 23, 32).

In the study of Faden et al. (9), 200 children were monitored from birth through to 2 years of age to determine the nasopharyngeal colonization pattern of nontypeable H. influenzae. Forty-four percent of the children were colonized on one or more occasions, and the acquisition rate was greatest in the first year. Colonization mainly involves a dominant strain which can be followed by a series of other strains (1, 9, 15, 24). The level of carriage varies according to different factors, i.e., age, siblings, and living conditions. All of these factors can also have repercussions on the carriage of strains resistant to antibiotics or encapsulated type b strains. Anti-Hib vaccination has led to a sharp drop in the carriage of encapsulated type b strains (33).

The turnover of noncapsulated H. influenzae strains in the nasopharynx of healthy children and of otitis-prone children has been the object of several studies (9, 24, 27, 29, 35). These results were obtained in children attending or not attending day care centers (DCCs) or living in orphanages.

The present study was designed to monitor nasopharyngeal carriage of H. influenzae in healthy children attending DCCs in three different geographic areas of France. The technique of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was used to characterize the epidemiology of H. influenzae colonization of children in the DCC and in the whole geographic area. Our goals were to determine whether the children were colonized with specific strains in a given geographic area, whether the same strains were observed over a period of time, what their turnover was between the seasons, and what was the profile of the β-lactamase-producing strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial sampling.

H. influenzae strains were isolated from nasopharyngeal aspirates of children aged 3 to 36 months attending DCCs in three well-separated areas of France (Alpes Maritimes, southeastern France; Doubs, central eastern France; and Nord, north) in May to June 1999 and November to December 1999.

Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee (Comité Consultatif pour la Protection des Personnes dans la Recherche Biomédicale, Aix en Provence, France, 1 December 1998), and in each area, the study was initiated with the agreement of the local health authority and of the DCC manager. Parental consent was obtained and a questionnaire was completed for each participant providing information regarding a subject's age, sex, family size, history of recent respiratory infection or antibiotic therapy and vaccine status (in particular, the anti-Hib status). In each area, the DCCs were randomized for the two study periods. In each DCC, and for each study period, the children were randomly selected among those for whom written parental consent had been given. Randomization was done by using a two-stage sampling method choosing the primary units (DCC) with probability proportional to size.

Nasopharyngeal samples were obtained by using a silicon cannula with a flexible tube fixed onto a syringe (Vygon, Paris, France). The tubes were transported in transport medium (Portagerm; bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) to a designated hospital bacteriology laboratory in each area.

Specimens were plated on chocolate agar and sheep blood agar plates (bioMérieux) and incubated overnight at 37°C (under a CO2-enriched atmosphere for chocolate agar plates). H. influenzae isolates were identified according to standard microbiological procedures (25). Isolates were kept frozen locally at −70°C before being sent to the H. influenzae National Reference Center in Toulouse, France.

Bacteriological methods.

Capsular typing was done by slide agglutination with type-specific antiserums a to f (Difco, BD, Le Pont de Claix, France). The capsular type was confirmed by molecular typing with the primers and methods reported by Falla et al. (10).The biotype was determined as described by Kilian (19).The production of β-lactamase was assessed by a chromogenic cephalosporin test (Nitrocefine; bioMérieux). The β-lactamase type, TEM or ROB, was determined by PCR by using the primers for blaTEM and blaROB proposed by Tenover et al. (34). Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by the disk diffusion test on Haemophilus test medium (18) with purchased disks (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France) and by MIC determination by an agar dilution method which used Haemophilus test medium agar with an inoculum of 104 cells per spot (5).

PFGE.

PFGE was performed as described previously (7) with a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field system (CHEF DR III apparatus; Bio-Rad Laboratories). PFGE fingerprints were analyzed with Bio-Profil 99 software, Bio-1D software was used for the gel analysis, and Biogene software was used for pattern comparison (Vilber Lourmat, Marne La Vallée, France). The similarity of the PFGE banding patterns was estimated with the Dice coefficient and the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic average algorithm.

Various dendrograms were obtained: one with the genotypes of all strains, one with the genotypes of the strains isolated in May to June, one with the genotypes of the strains isolated in November to December, and those with the genotypes of the strains from each area period by period. Each dendrogram is composed of restriction patterns for single isolates or for two or more isolates. The diversity index (DI) is defined as the ratio of the number of restriction patterns to the number of strains. An index close to 1 represents maximum diversity or heterogeneity; an index of 0.01 indicates maximum clonality or identity. The diversity is also assessed by the percentage of patterns for a single isolate (percentage of the number of patterns for single isolates over the number of patterns). A percentage close to 100 represents maximum heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by using EPI-INFO 6.4.fr software.

RESULTS

During the two periods, May to June and November to December 1999, 1,683 children aged 3 to 36 months attending DCCs were studied. The DCCs were located in the Alpes Maritimes (n = 24), Doubs (n = 21), and Nord (n = 20) areas. They were randomly selected, which guarantees representation of the children attending DCCs in the three different areas. The mean age was 20 months. About half of the children were male (53.2%). Among all the children included in the study, 98.5% had received at least one anti-Hib vaccine dose. Owing to the hazards of the randomization process, 51 children who were carriers of H. influenzae in the May-to-June period were also selected in the November-to-December period and were also carriers of H. influenzae. There were 7 such children in the Alpes Maritimes area, 16 such children in the Doubs area, and 28 such children in the Nord area.

The characteristics of the strains according to the area and the period are shown in Table 1. Overall, the carriage rate of H. influenzae was 40.9% (688 out of 1,683 children), with a carriage peak between 21 and 24 months (56%). The prevalence of encapsulated H. influenzae carriers in children under 3 years was 1% (17 of 1,683), the prevalence for type f was 0.4% (7 of 1,683), and the prevalence for type e was 0.6% (10 of 1,683). None of the isolates were of type b.

TABLE 1.

Carriage and characteristics of H. influenzae strains isolated during the two periods (year 1999) from children attending DCCs in three different geographic areas of France

| Parameter | Result for area and study period

|

Overall result | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpes Maritimes

|

Doubs

|

Nord

|

|||||

| May-June | November-December | May-June | November-December | May-June | November-December | ||

| No. of children included | 313 | 298 | 326 | 297 | 240 | 209 | 1,683 |

| No. of strains isolated (%)a,b | 109 (34.8) | 107 (35.9) | 118 (36.2) | 114 (38.4) | 141 (53.8) | 99 (47.4) | 688 (40.9) |

| Capsular type | |||||||

| e | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | ||

| f | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | |||

| NTc | 109 | 103 | 115 | 113 | 137 | 94 | 671 |

| No. of β-lactamase-positive strains (%) | 44 (40.4) | 42 (39.3) | 56 (47.5) | 63 (55.3) | 60 (42.6) | 41 (41.4) | 306 (44.5) |

| No. of BLNARd | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 9 | ||

For May to June, Alpes Maritimes versus Doubs versus Nord, P < 0.001.

For November to December, Alpes-Maritimes versus Doubs versus Nord, P = 0.001.

NT, not typeable.

BLNAR, β-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant strains.

Among the strains, 306 (44.5%) were β-lactamase producers and all of the β-lactamase-positive strains gave a positive result with specific primers for the blaTEM gene. No ROB-type enzyme was characterized among the β-lactamase-positive strains. The prevalence rate of carriers of β-lactamase-positive strains was 18.2% (306 of 1,683). Nine strains exhibited decreased susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics without β-lactamase production. They represent 1.3% (9 of 688) of the strains and concern 0.53% (9 of 1,683) of the children.

H. influenzae carriage during the May-to-June 1999 period.

During the May-to-June 1999 period, nasopharyngeal samples were taken from a total of 879 children. Overall, the carriage rate of H. influenzae was 41.8% (368 of 879). From area to area, H. influenzae carriage was 34.8% in Alpes Maritimes, 36.2% in Doubs, 58.8% in Nord (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Among the strains, 7 were capsulated, 3 were of type f (0.8%) and 4 were of type e (0.9%), and isolated in the Doubs and Nord areas. For the whole set (160 of 368), 43.4% of the strains were TEM-type β-lactamase producers. The percentage of strains producing β-lactamase was 40.3, 47.4, and 42.5% in Alpes Maritimes, Doubs, and Nord, respectively (P = 0.54). The carriage rate of β-lactamase-producing strains by children was 14.05% in the Alpes Maritimes, 17.2% in Doubs, and 25% in Nord (Table 1) (P = 0.003).

H. influenzae carriage during the November-to-December period.

During this period, 804 children were included for the three areas. Among them, 320 (39.8%) were H. influenzae carriers, i.e., 35.9% in Alpes Maritimes, 38.3% in Doubs, and 47.3% in Nord (P = 0.03). Ten of the corresponding strains were encapsulated (3.1%) (10 of 320), 4 (1.2%) were type f in the Alpes Maritimes and 6 (1.8%) were type e in the Doubs and Nord areas. TEM-type β-lactamase-producing strains accounted for 46.5% (149 of 320). The proportion of strains producing β-lactamase was 39.2, 54.3, and 42.4% in the Alpes Maritimes, Doubs, and Nord, respectively (P = 0.035). The carriage rate of β-lactamase-producing strains was 14.1% in Alpes Maritimes, 21.2% in Doubs, and 19.6% in Nord (P = 0.065).

PFGE.

From the 688 strains, 25 repeatedly yielded unsatisfactory weak pulsed-field gel electropherograms or were lost and were omitted from further investigations.

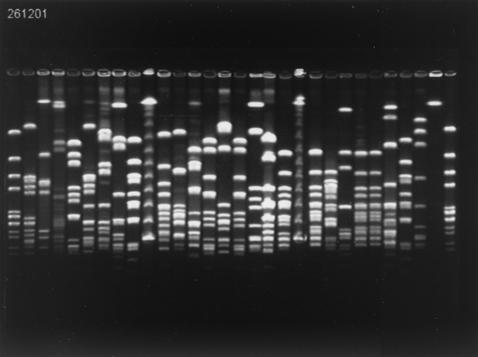

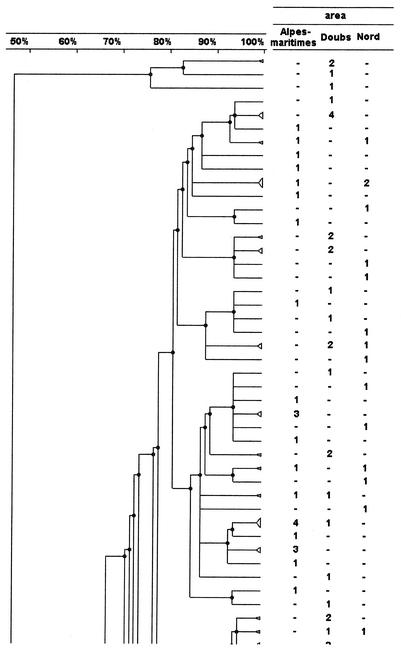

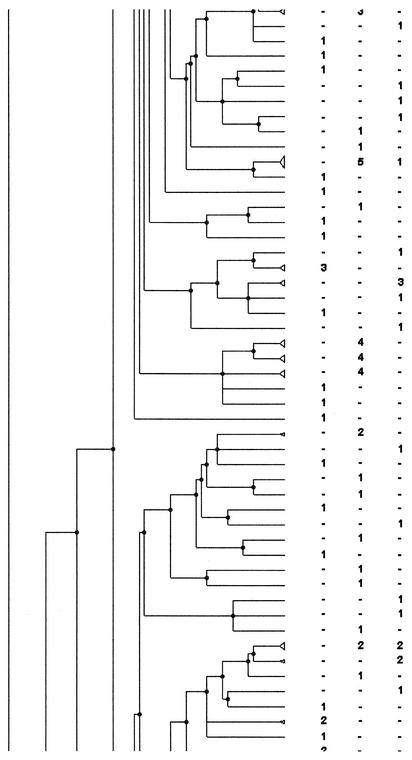

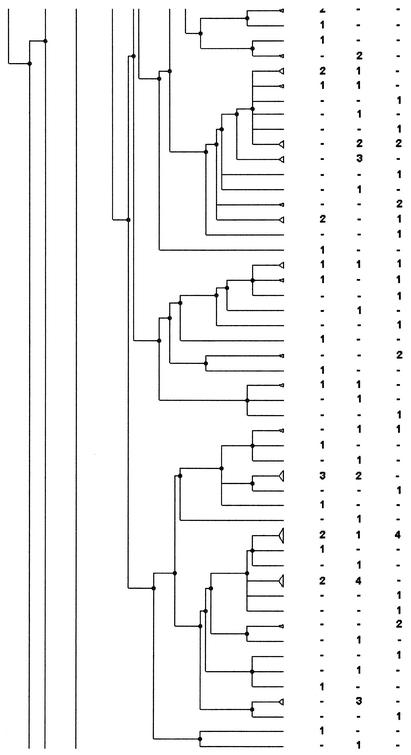

An example of PFGE fingerprints obtained after SmaI digestion is shown in Fig. 1. Analysis was carried out by using various dendrograms: that obtained from the PFGE fingerprints of the whole set of strains (663 strains), those obtained with the strains from each period (May to June, 353 strains; November to December, 310 strains) (Fig. 2), and those obtained with the strains from each area including just one or both of the periods (Fig. 3).

FIG. 1.

PFGE profiles of SmaI-restricted H. influenzae DNA of strains isolated from children attending DCCs in the Doubs area during the November-to-December period. Lanes (left to right): 1, H. influenzae ATCC 10211; 2, child from DCC 04; 3 to 8, children from DCC 05; 9, child from DCC 06; 10, lambda ladder; 11, child from DCC 07; 12 to 17, children from DCC 08; 18 and 19, children from DCC 09; 20, lambda ladder; 21 to 25, children from DCC 09; 26, child from DCC 08; 27 and 28, children from DCC 06; 29, uninterpretable; 30, H. influenzae ATCC 10211.

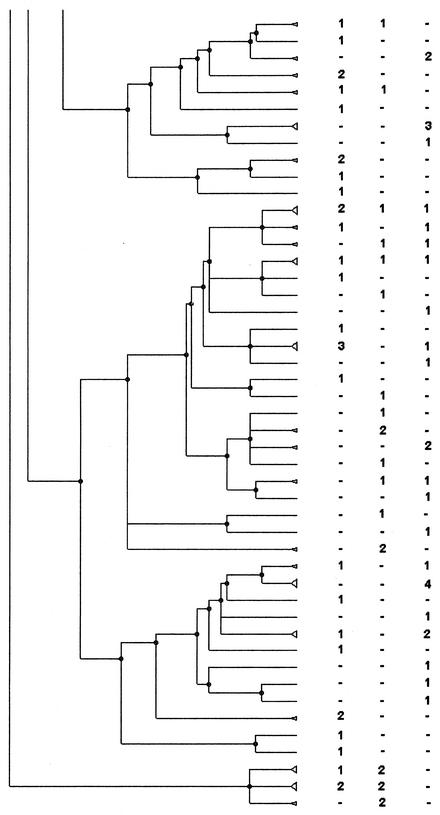

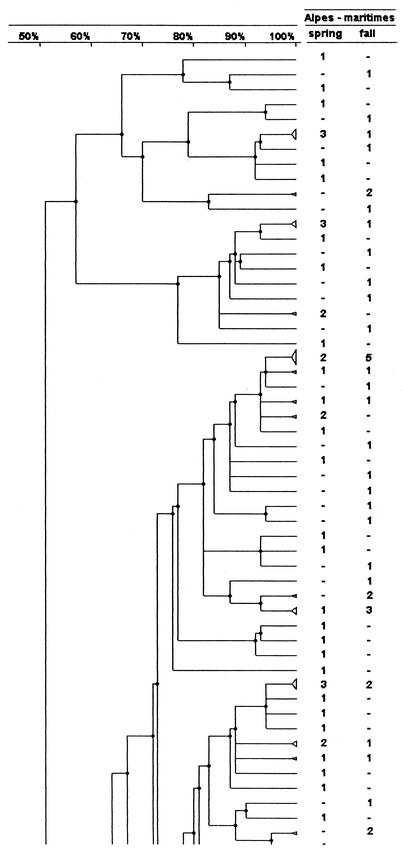

FIG. 2.

PFGE analysis dendrogram showing the genetic relationship among strains of H. influenzae isolated from children attending DCCs in three different geographic areas of France during the period from November to December 1999. For each area the number indicates the number of strains in the pattern; −, no strain in the pattern. The dendrogram is shown in four portions, in order from left to right, with the bottom of one portion corresponding to the top of the next.

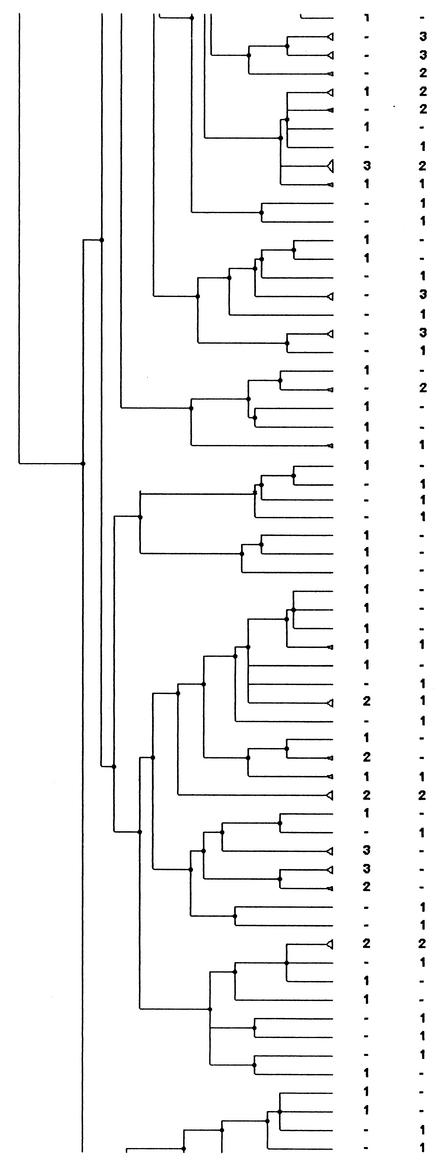

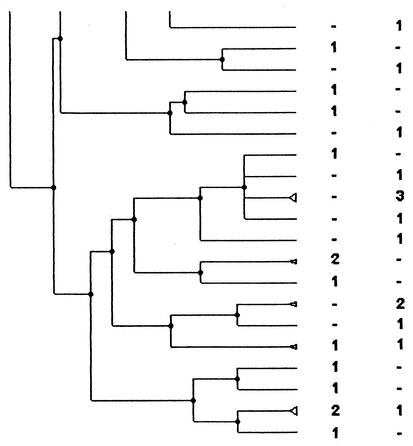

FIG. 3.

PFGE analysis dendrogram showing the genotypic relationship among strains of H. influenzae isolated from children attending DCCs in the Alpes Maritimes area during the two study periods. For each period the number indicates the number of strains in the pattern; −, no strain in the pattern. The dendrogram is shown in three portions, in order from left to right, with the bottom of one portion corresponding to the top of the next.

Among the 663 strains, 366 SmaI patterns were found, 224 were for a single isolate and the others (142) were patterns for 2 to 9 isolates. Among the 353 isolates from May to June and the 310 isolates from November to December, 239 and 189 patterns were found, respectively (167 and 123 for single isolates, respectively; the others were for 2 to 7 isolates) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of restriction pattern distribution of H. influenzae strains for the two study periods

| Parameter | Result for period:

|

Overall result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| May-June | November-December | ||

| No. of strains | 353 | 310 | 663 |

| No. of patterns | 239 | 189 | 366 |

| DI | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| % of patterns for single isolatesa | 69.8 | 65.1 | 61.2 |

| % of strains (no.) with same patterns in same DCCsb | 20.9 (74) | 35.4 (110) | 29.2 (194) |

| % of strains (no.) with new genotypesc | 57 (177) | ||

| % of strains (no.) with similar patterns from: | |||

| 2 or 3 areas | 33.4 (118) | 32.6 (101) | NDd |

| 2 areas | 28.3 (100) | 27.1 (84) | ND |

| 3 areas | 5.1 (18) | 5.4 (17) | ND |

| No. of patterns with strains from 2 or 3 areas (%) | 42 (17.5) | 32 (16.9) | ND |

Percentage of the number of patterns for single isolates over the number of patterns.

Percentage of the number of strains from a single DCC with the same pattern for 2 or more isolates over the number of strains.

Compared to the situation in the May-to-June period.

ND, not done.

Among the patterns with two or more isolates, the patterns and the strains coming from one DCC or one area were counted. Of the strains isolated during a same period, a third of the strains were in patterns simultaneously present in two or three areas: 118 strains (33.4%) in 42 patterns (17.5%) in May to June and 101 strains (32.6%) in 32 patterns (16.9%) in November to December. For the November-to-December period, the attribution of each pattern to an area is shown in Fig. 2.

The children who were carriers of H. influenzae during the May-to-June period and also in November to December had strains with different restriction patterns during the two periods.

According to the area and the period, the number of restriction patterns was between 81 and 115 for the May-to-June period and between 71 and 77 for the November-to-December period. The DI was always higher during the May-to-June period (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of restriction pattern distribution of H. influenzae strains according to the area and study period

| Parameter | Result for area and study period

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpes Maritimes

|

Doubs

|

Nord

|

|||||||

| May-June | November- December | Both | May-June | November- December | Both | May-June | November- December | Both | |

| No. of strains | 102 | 104 | 206 | 115 | 114 | 229 | 136 | 92 | 228 |

| No. of patterns | 81 | 77 | 135 | 88 | 71 | 143 | 115 | 72 | 172 |

| DI | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| % of patterns for single isolatesa | 80 | 75 | 71 | 77 | 64 | 61 | 86 | 81 | 78 |

| % of strains (no.) with same patterns in same DCCsb | 19.6 (20) | 28.8 (30) | 32.0 (66) | 27.8 (32) | 48.2 (55) | 40.1 (92) | 12.5 (17) | 32.6 (30) | 21.9 (50) |

| % of strains (no.) with new genotypesc | 70.2 (73) | 68.4 (78) | 72.8 (67) | ||||||

| No. of new patternsc | 54 | 52 | 56 | ||||||

Depending on the area, 52 to 56 new patterns were observed among the strains isolated in November to December. The percentage of strains in new genotypes during the period from November to December compared to the situation of May to June was 68 to 72% (Table 3). For each area, there was a persistence of about 30% (27.2 to 31.6%) of the strains after the 6 months separating the two study periods among the carrier children, i.e., a turnover of about 70% of the strains.

Among the 306 TEM-type β-lactamase-producing strains, 297 were studied by PFGE and 194 patterns were found, including 103 patterns for single isolates. Within the same pattern, β-lactamase-producing strains can coexist alongside non-β-lactamase-producing strains.

Depending on the area, 24 to 28 new patterns were observed among the strains isolated in November to December. The percentage of strains in new genotypes during this period, compared to the situation in May to June, was 66 to 73% (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of restriction pattern distribution of β-lactamase-producing H. influenzae strains according to the area and study period

| Parameter | Result for area and study period

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpes Maritimes

|

Doubs

|

Nord

|

|||||||

| May-June | November-December | Both | May-June | November-December | Both | May-June | November-December | Both | |

| No. of strains | 40 | 41 | 81 | 54 | 63 | 117 | 60 | 39 | 99 |

| No. of patterns | 32 | 33 | 59 | 46 | 38 | 77 | 54 | 31 | 79 |

| DI | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| % of patterns (no.) for single isolatesa | 81 (26) | 72 (24) | 67 (40) | 78 (36) | 60 (23) | 58 (45) | 83 (45) | 80 (25) | 74 (59) |

| % of strains (no.) with same patterns in same DCCsb | 27.5 (11) | 26.8 (11) | 30.8 (25) | 14.8 (8) | 50.7 (32) | 34.2 (40) | 10 (6) | 35.9 (14) | 20.2 (20) |

| % of strains (no.) with new genotypesc | 73.2 (30) | 73 (46) | 66.6 (26) | ||||||

| No. of new patternsc | 26 | 28 | 24 | ||||||

DISCUSSION

This study focuses on the characterization of H. influenzae strains colonizing children attending DCCs in three different and remote geographic areas during two periods: May to June and November to December. The mean carriage rate of H. influenzae found was 40.9%, with 41.8% in May to June and 39.8% in November to December. These values are close to those of earlier studies carried out with healthy children in DCCs (39%, range 32 to 47%) and with children living in orphanages (45%, range 17 to 70%) (8, 27, 35). In the Nord area on the vicinity of the North Sea, there was a higher proportion of H. influenzae carriers than in the other study areas. This could be related to differences in DCC sizes, number of siblings per family, and particularly when comparing the area with the Mediterranean character of the Alpes Maritimes, differences in climate. Our study also confirms the impact of anti-Hib vaccination on the carriage of encapsulated type b strains, and in this population where 98% of the children had received at least one injection of vaccine, no children were carriers of type b strains (9, 22, 33).

Carriage of encapsulated strains other than type b was low: 0.4% carriers of type f and 0.6% carriers of type e. These two capsular types are usually found in children of preschool age (11, 23) and school age (3) or living in orphanages (27).

High genetic heterogeneity of nontypeable H. influenzae isolates has been reported in previous studies whatever the epidemiological markers used (4, 14, 21, 29, 30). Among 178 epidemiologically unrelated isolates, Saito et al. found 165 genotypes (28). On the other hand, among the 111 strains isolated from children living in the closed community of an orphanage, only 13 PFGE profiles were detected, with 83% of the isolates belonging to 5 patterns (27). In our study concerning the strains of H. influenzae colonizing children attending DCCs, 366 genotypes were found for 663 strains.

This study did not focus on the fate of the colonization in one child, like in the investigations of Trottier et al. (35) and Raymond et al. (27). It did not, therefore, assess the dynamics and the diversity of colonization in individual children. It does, however, provide a picture of the dynamics and the diversity of colonization in a community made up of children attending a DCC in a geographic area and finally in three areas during two periods 5 to 6 months apart.

A comparison of strains isolated during the same period in the three areas, providing an image on the national scale, shows that a third of the strains were simultaneously present in the three areas. This corresponds to the dispersion of strains (genotypes) in a population of children who are geographically remote and who have no contact. The same dispersion of the strains is observed on the scale of the area; children attending different DCCs are carriers of strains with the same genotype.

During a prospective study carried out with three children attending a DCC, it was shown that colonization of the nasopharynx by H. influenzae was a dynamic process corresponding to the carriage of a single strain for several months, the loss of this strain followed by the acquisition of a new strain (31). This same dynamic colonization process is also shown in the study by Trottier et al. (35) where, in the same children, there are resident strains and transient strains; after acquisition and carriage of a strain, there is loss followed or not by the acquisition of a new strain.

Among the children participating in the present study, colonization is also seen to be a dynamic process with persistence—in the whole population, not in individual children—of only 30% of the strains at a 6-month interval. This renewal of almost 70% of the strains was observed independently in the three geographic areas. It cannot be totally attributed to different children being recruited for the two study periods and stresses the diversity and the genetic heterogeneity of the nontypeable strains of H. influenzae.

Such a change of genotypes could be due to the introduction of new strains or to strains already present but undetected. Horizontal transfer of strains has been observed in DCCs for pneumococcus, with a turnover of 64% of the strains in the same children in the absence of selection pressure by antibiotics (2).

These high rates of clonal replacement have also been observed for Streptococcus mitis, which undergoes constant change in its natural habitat, the mouth and pharynx, among the members of a family. The strains of S. mitis colonizing the adults and children of one family belong to a multitude of distinct genotypes and change continually. This type of dynamics in the S. mitis population can result from exchanges within the family unit (but in fact few have been detected) or from the passage from one habitat to another (mouth and pharynx) or it could be due to in situ recombination (16).

For H. influenzae, this type of situation has not been reported. However, the fact that strains with reduced sensitivity to ampicillin and having the same genotype are found in adults and children supports the notion of the exchange of strains between the two populations and can partly explain the renewal of the strains colonizing children (7). So, the diversity is not thought to be simply due to exchanges of strains within DCCs leading to increased heterogeneity or genomic diversity but also to exchanges with adult subjects.

The carriage of strains resistant to antibiotics and in particular to β-lactam is a source of concern in numerous countries and involves both Streptococcus pneumoniae and H. influenzae. In H. influenzae, it is the production of TEM-type β-lactamase that is the most frequent. Unlike in other countries, where the prevalence of β-lactamase is low (lower than 10%) (17, 26), in France the frequency of β-lactamase-producing strains is high, over 35%, in particular for strains isolated from the nasopharynx or those causing acute otitis media (6, 13, 27).

In the present study, 44.5% of the strains produced TEM-type β-lactamase. These strains showed a genomic diversity comparable to that of the whole set of strains. In addition, the dynamics of colonization by β-lactamase-producing strains is also comparable to that of the sensitive strains with, depending on the area, a renewal rate of 66 to 73% of the strains over the 6-month study period. The spread of strains producing β-lactamase does not correspond to clonal expansion under selection pressure (or not) from β-lactam antibiotics. This result does not support the implantation of one or several strains in an area followed by their expansion and stability over time. It rather suggests acquisition of resistance by the transfer of genes, as of plasmids or transposons. The molecular epidemiology of these genetic elements should be able to confirm this hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

The first part of this study (OTIFLOR project) was financed by Roche Laboratories. M.P.-S. was directly supported by Roche Laboratories. This research received grants from Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse (AT-UPS 2000).

We thank all those who participated in the OTIFLOR study: Bruno Grandbastien, Alain Martinot, Nathalie Bernard-Rémy, and Sandrine Piechel, CHRU Lille; Brigitte Dunais, CHU Nice; Jean-Marie Estavoyer, CHU Besançon; and Didier Guillemot, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein, J. M., D. Dryja, N. Yuskiw, and T. F. Murphy. 1997. Analysis of isolates recovered from multiple sites of the nasopharynx of children colonized by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:750-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogaert, D., M. N. Engelen, A. J. M. Timmers-Reker, K. P. Elzenaar, P. G. H. Peerbooms, R. A. Coutinho, R. De Groot, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2001. Pneumococcal carriage in children in The Netherlands: a molecular epidemiological study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3316-3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bou, R., À. Domínguez, D. Fontanals, I. Sanfeliu, I. Pons, J. Renau, V. Pineda, E. Lobera, C. Latorre, M. Majó, L. Salleras, and the Working Group on invasive disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae. 2000. Prevalence of Haemophilus influenzae pharyngeal carriers in the school population of Catalonia. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce, K. D., and J. Z. Jordens. 1991. Characterization of noncapsulate Haemophilus influenzae by whole-cell polypeptide profiles, restriction endonuclease analysis, and rRNA gene restriction patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:291-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. Communiqué 2002. [Online.] http://www.sfm.asso.fr/Sect4/com2002.pdf.

- 6.Dabernat, H., P. Geslin, F. Megraud, P. Bégué, J. Boulesteix, C. Dubreuil, F. de La Roque, A. Trinh, and A. Scheimberg. 1998. Effects of cefixime or co-amoxiclav treatment on nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae in children with acute otitis media. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dabernat, H., C. Delmas, M. Seguy, R. Pelissier, G. Faucon, S. Bennamani, and C. Pasquier. 2002. Diversity of β-lactam-resistance-conferring amino acid substitutions in penicillin-binding protein 3 of Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2208-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faden, H., M. J. Waz, J. M. Bernstein, L. Brodsky, J. Stanievich, and P. L. Ogra. 1991. Nasopharyngeal flora in the first three years of life in normal and otitis-prone children. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 100:612-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faden, H., L. Duffy, A. Williams, D. A. Krystofik, and J. Wolf. 1995. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal colonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the first 2 years of life. J. Infect. Dis. 172:132-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falla, T. J., D. W. M. Crook, L. N. Brophy, D. Maskell, J. S. Kroll, and E. R. Moxon. 1994. PCR for capsular typing of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2382-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontanals, D., R. Bou, I. Pons, I. Sanfeliu, A. Domínguez, V. Pineda, J. Renau, C. Muñoz, C. Latorre, F. Sanchez, and the Working Group on Invasive Disease Caused by Haemophilus influenzae. 2000. Prevalence of Haemophilus influenzae carriers in the Catalan preschool population. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:301-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foxwell, A. R., J. M. Kyd, and A. W. Cripps. 1998. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenesis and prevention. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:294-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gehanno, P., B. Barry, and P. Berche. 1977. Acute childhood otitis media: the diagnostic value of bacterial samples from the nasopharynx. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 3(Suppl. 3):34-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez-de-Leon, P., J. I. Santos, J. Caballero, D. Gomez, L. E. Espinoza, I. Moreno, D. Piñero, and A. Cravioto. 2000. Genomic variability of Haemophilus influenzae isolated from Mexican children determined by using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequences and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2504-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper, M. B. 1999. Nasopharyngeal colonization with pathogens causing otitis media: how does this information help us? Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:1120-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohwy, J., J. Reinholdt, and M. Kilian. 2001. Population dynamics of Streptococcus mitis in its natural habitat. Infect. Immun. 69:6055-6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard, A. J., K. T. Dunkin, and G. W. Millar. 1988. Nasopharyngeal carriage and antibiotic resistance of Haemophilus influenzae in healthy children. Epidemiol. Infect. 100:193-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jorgensen, J. H., J. S. Redding, L. A. Mahe, and A. W. Howell. 1987. Improved medium for antimicrobial susceptibility tests of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2105-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilian, M. 1976. A taxonomic study of the genus Haemophilus, with the proposal of a new species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 93:9-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein, J. O. 1997. Role of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pediatric respiratory tract infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:S5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loos, B. G., J. M. Bernstein, D. M. Dryja, T. F. Murphy, and D. P. Dickinson. 1989. Determination of the epidemiology and transmission of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in children with otitis media by comparison of total genomic DNA restriction fingerprints. Infect. Immun. 57:2751-2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madore, D. V. 1996. Impact of immunization on Haemophilus influenzae type b disease. Infect. Agents Dis. 5:8-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moxon, E. R. 1986. The carrier state: Haemophilus influenzae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 18(Suppl. A):17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy, T. F., J. M. Bernstein, D. M. Dryja, A. A. Campagnari, and M. A. Apicella. 1987. Outer membrane protein and lipooligosaccharide analysis of paired nasopharyngeal and middle ear isolates in otitis media due to nontypable Haemophilus influenzae: pathogenetic and epidemiological observations. J. Infect. Dis. 156:723-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray, P. R., E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.). 1999. Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Principi, N., P. Marchisio, G. C. Schito, S. Mannelli, and the Ascanius Project Collaborative Group. 1999. Risk factors for carriage of respiratory pathogens in the nasopharynx of healthy children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:517-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raymond, J., L. Armand-Lefevre, F. Moulin, H. Dabernat, A. Commeau, D. Gendrel, and P. Berche. 2001. Nasopharyngeal colonization by Haemophilus influenzae in children living in an orphanage. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:779-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito, M., A. Umeda, and S.-I. Yoshida. 1999. Subtyping of Haemophilus influenzae strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2142-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuelson, A., A. Freijd, J. Jonasson, and A. A. Lindberg. 1995. Turnover of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in the nasopharynges of otitis-prone children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2027-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Vaughan, H. C., A. J. Leach, T. M. Shelby-James, K. Kemp, D. J. Kemp, and J. D. Mathews. 1996. Carriage of multiple ribotypes of non-encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae in aboriginal infants with otitis media. Epidemiol. Infect. 116:177-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinola, S. M., J. Peacock, F. W. Denny, D. L. Smith, and J. G. Cannon. 1986. Epidemiology of colonization by nontypable Haemophilus influenzae in children: a longitudinal study. J. Infect. Dis. 154:100-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.St. Geme, J. W., III. 2000. The pathogenesis of non typable Haemophilus influenzae otitis media. Vaccine 19:S41-S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takala, A. K., J. Eskola, M. Leinonen, H. Käyhty, A. Nissinen, E. Pekkanen, and P. H. Mäkelä. 1991. Reduction of oropharyngeal carriage of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) in children immunized with an Hib conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 164:982-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenover, F. C., M. B. Huang, J. K. Rasheed, and D. H. Persin. 1994. Development of PCR assays to detect ampicillin resistance genes in cerebrospinal fluid samples containing Haemophilus influenzae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2729-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trottier, S., K. Stenberg, and C. Svanborg-Eden. 1989. Turnover of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae in the nasopharynges of healthy children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2175-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turk, D. C., and J. R. May. 1967. Haemophilus influenzae. Its clinical importance. English University Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 37.Wenger, J. D. 1994. Impact of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines on the epidemiology of bacterial meningitis. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:324-332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]